| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hechmi Toumi | + 3106 word(s) | 3106 | 2021-03-01 07:36:37 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | -2040 word(s) | 1066 | 2021-03-08 09:08:24 | | |

Video Upload Options

Osteoarthritis (OA) is a complex degenerative disease in which joint homeostasis is disrupted, leading to synovial inflammation, cartilage degradation, subchondral bone remodeling, and resulting in pain and joint disability.

1. Introduction

Osteoarthritis (OA) is the most common degenerative musculoskeletal disease and is a leading cause of disability in the adult population [1]. OA is a whole-joint disease that is characterized by irreversible cartilage degradation; disruption of the tidemark, accompanied by angiogenesis and cartilage calcification; subchondral bone remodeling; osteophyte formation; mild-to-moderate inflammation of the synovial lining [2][3][4]. The most common risk factors for OA include age, prior joint injury, obesity, muscle atrophy, metabolic disorders, and mechanical stress [5][6]. The disease evolution is typically slow and can take years to develop, with resultant joint pain and stiffness, mobility limitations, and compromised quality of life. Despite the tremendous personal and societal burden of OA, there are no curative treatments available and most conventional therapies (medications, physiotherapy, mechanical devices) provide relatively short-term, unsustained relief of the symptoms [7][8][9][10][11].

Promise exists for emerging disease-modifying drugs in the management of OA patients that regulate cartilage metabolism, subchondral bone remodeling, synovial inflammation, and angiogenesis. Recently, the use of plant-derived natural products has increased because of their therapeutic value in bone health, which is attributable to their chondroprotective and osteoprotective properties [12][13]. Many of these natural products have been reported to have anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, anti-catabolic effects on chondrocytes, and inhibitory effects on osteoclast differentiation [14][15][16].

2. Natural-Compound-Based Treatments for OA Therapy

Conventional pharmaceutical agents (steroids or non-steroids anti-inflammatory (NSAIDs) drugs) have small-to-moderate effects in patients with OA [7][9][11][17][18][19]. Accordingly, there is an increasing interest in identifying novel approaches, including the use of natural bioactive components that could promote joint health, and mitigate and/or reverse OA [20].

2.1. Alkaloids

Berberine

Berberine is an alkaloid (benzylisoquinoline) that is found in medicinal plants of the genera Berberis, such as Berberis vulgaris, and is usually found in the roots, rhizomes, and stems (Table 1) [21]. It has been reported that berberine has anti-osteoarthritic effects [21]. In vivo studies in two different OA animal models (collagenase- and surgically induced OA) have demonstrated that berberine has chondroprotective effects, which ameliorates cartilage degradation while inducing chondrocyte proliferation [22][23]. It has been shown that berberine inhibits chondrocyte apoptosis and cartilage degradation via activating AMPK signaling and suppressing p38 MAPK activity [24][25]. Berberine also decreases inflammation and cartilage degradation by modulating the host immune response through the inhibition of TLR4/NF-κB signaling [26]. Moreover, berberine has been associated with bone formation by promoting osteogenic differentiation via activation of Runx-2 and p38 MAPK and reducing osteoclast differentiation [27][28].

Table 1. Natural-alkaloid-based pharmacology therapy for osteoarthritis (OA).

|

Compound (Source) |

Category |

Structure |

Therapeutic Target |

Treatment |

Ref |

|

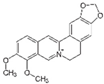

Berberine (Berberis vulgaris) |

Benzyl isoquinolin alkaloid |

|

Activation of AMPK signaling and inhibition of p38 MAPK/NF-κB pathways in chondrocytes. Activation of p38 MAPK signaling in osteoblasts. |

Anti-inflammatory, anti-apoptotic, and anti-degradation in cartilage; Induction of bone formation. |

2.2. Flavonoids

2.2.1. Apigenin

Apigenin is a flavonoid (4′,5,7-trihydroxyflavone) that is found in herbs (chamomile, thyme), fruits (orange), vegetable oils (extra virgin olive oil), and in plant-based beverages (tea, beer, and wine) (Table 2) [29]. This bioactive agent has already been used as therapeutic therapy against diabetes, cancer, Alzheimer’s disease, and OA [30][31]. Apigenin has anti-inflammatory properties through inhibiting IL-1β/NF-κB and TGFβ/Smad2/3 pathways in chondrocytes [32]. Park et al. have demonstrated that apigenin blocks cartilage degradation in in vitro and in vivo OA mouse models through Hif-2α inhibition and the consequent downregulation of MMP-3, MMP-13, ADAMTS-5, and ADAMTS-4 in articular chondrocytes [33]. Furthermore, apigenin has shown bone protective effects via modulating the gene expression of TGF-β1 and its receptors, BMP-2, BMP-7, ALP, and collagen type I in MG63 osteoblasts [34]. Apigenin also promotes osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells through the JNK and p38 MAPK pathways [35].

2.2.2. Astragalin

Astragalin is a natural flavonoid (kaempferol 3-glucoside) found in various traditional medicinal plants, such as Cuscuta chinensis. Its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory therapeutic properties have led some to consider its potential as a therapeutic agent for OA patients [36][37]. According to Ma et al. [38], astragalin inhibits the IL-1β-stimulated activation of NF-κB and MAPK in the chondrocytes of patients with OA while suppressing inflammation and bone destruction in a mouse model of OA [38][39].

2.2.3. Baicalein

Baicalein is a flavonoid (5,6,7-trihydroxyflavone) that is isolated from the roots of Scutellaria baicalensis and Scutellaria lateriflora and has medicinal properties, including neuroprotective, anti-oxidant, anti-fibrosis, and anti-cancer properties [40][41]. Recently, it has been demonstrated that baicalein has anti-catabolic and anti-apoptotic effects through inhibiting IL-1β induction in chondrocytes [42][43]. Another study showed that the intra-articular injection of medium and high doses of baicalein alleviated OA progression in a rabbit OA model, diminishing cartilage degradation, and showing a lower Mankin score [44]. Similarly, positive results were obtained on bone through the induction of osteoblast differentiation and inhibiting osteoclast differentiation [45][46].

2.2.4. Chrysin

Chrysin is a flavonoid (5,7-dihydroxyflavone) that is found in various medicinal plants, such as Scutellaria baicalensis and Passiflora caerulea, but also in honey and propolis [47]. In human osteoarthritic chondrocytes, chrysin showed a suppressive effect on the IL-1β-induced inflammatory response, including the expression of inducible nitrous oxide synthase (iNOS), COX-2, MMP-1, MMP-3, MMP-13, ADAMTS-4, and ADAMTS-5 via the inhibition of NF-κB signaling and decreases in the concentrations of nitrous oxide (NO) and PGE2. Chrysin also inhibits the degradation of aggrecan and collagen-II [48]. In addition, chrysin attenuates the apoptosis and inflammation of stimulated human OA chondrocytes via the suppression of high-mobility group box chromosomal protein (HMGB-1) [49]. An osteoprotective effect was also observed under chrysin treatment via ERK/MAPK activation and the upregulating of Runx-2 and Osx expression [50][51].

2.2.5. Genistein

Genistein is a flavonoid (isoflavone) and a phytoestrogen that is extracted from Genista tinctoria. It has been reported to have promising benefits in the treatment of several pathologies [52][53][54]. The anti-osteoarthritic activity of genistein is suggested to be due to the relationship between OA and altered estrogen metabolism [55]. Phytoestrogens have some estrogen activity and ameliorate menopausal symptoms, bone loss, and symptoms of OA [56][57]. In vitro, genistein suppresses catabolic effects of IL-1β-induced in human OA chondrocytes by targeting the Nrf2/HO-1 pathway, decreasing the expression of MMPs, nitric oxide synthase 2 (NOS2), and COX-2 [58]. In vivo, genistein attenuated cartilage degradation in two different OA animal models [58][59]. Furthermore, a positive effect on bone was obtained through enhanced osteoblastic differentiation and maturation via the activation of ER (estrogen receptor), p38 MAPK–Runx2, and NO/cGMP pathways [60][61][62]. It also inhibited osteoclast formation and bone resorption by inducing the osteoclastogenic inhibitor osteoprotegerin (OPG) and by blocking NF-κB signaling [60][63].

References

- Brennan-Olsen, S.L.; Cook, S.; Leech, M.T.; Bowe, S.J.; Kowal, P.; Ackerman, N.; Page, R.S.; Hosking, S.M.; Pasco, J.A.; Mohebbi, M. Prevalence of arthritis according to age, sex and socioeconomic status in six low and middle income countries: Analysis of data from the World Health Organization study on global AGEing and adult health (SAGE) Wave 1. BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2017, 18, 271, doi:1186/s12891-017-1624-z.

- Loeser, R.F.; Goldring, S.R.; Scanzello, C.R.; Goldring, M.B. Osteoarthritis: A disease of the joint as an organ. Arthritis Rheum. 2012, 64, 1697–1707, doi:10.1002/art.34453.

- Goldring, S.R.; Goldring, M.B. Changes in the osteochondral unit during osteoarthritis: Structure, function and cartilage–bone crosstalk. Rev. Rheumatol. 2016, 12, 632–644, doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2016.148.

- Burr, D.B.; Gallant, M.A. Bone remodelling in osteoarthritis. Rev. Rheumatol. 2012, 8, 665–673, doi:10.1038/nrrheum.2012.130.

- Berenbaum, F.; Wallace, I.J.; Lieberman, D.E.; Felson, D.T. Modern-day environmental factors in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis. Rev. Rheumatol. 2018, 14, 674–681, doi:10.1038/s41584-018-0073-x.

- Palazzo, C.; Nguyen, C.; Lefevre-Colau, M.-M.; Rannou, F.; Poiraudeau, S. Risk factors and burden of osteoarthritis. Phys. Rehabil. Med. 2016, 59, 134–138, doi:10.1016/j.rehab.2016.01.006.

- Da Costa, B.R.; Reichenbach, S.; Keller, N.; Nartey, L.; Wandel, S.; Jüni, P.; Trelle, S. Effectiveness of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for the treatment of pain in knee and hip osteoarthritis: A network meta-analysis. Lancet 2017, 390, e21–e33, doi:101016/S0140-6736(17)31744-0.

- Spetea, M. Opioid Receptors and Their Ligands in the Musculoskeletal System and Relevance for Pain Control. Pharm. Des. 2014, 19, 7382–7390, doi:10.2174/13816128113199990363.

- Osani, M.C.; Bannuru, R.R. Efficacy and safety of duloxetine in osteoarthritis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2019, 34, 966–973, doi:10.3904/kjim.2018.460.

- Oo, W.M.; Liu, X.; Hunter, D.J. Pharmacodynamics, efficacy, safety and administration of intra-articular therapies for knee osteoarthritis. Expert Opin. Drug Metab. Toxicol. 2019, 15, 1021–1032, doi:10.1080/17425255.2019.1691997.

- Bannuru, R.R.; Osani, M.C.; Vaysbrot, E.E.; Arden, N.K.; Bennell, K.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.A.; Kraus, V.B.; Lohmander, L.S.; Abbott, J.H.; Bhandari, M.; et al. OARSI guidelines for the non-surgical management of knee, hip, and polyarticular osteoarthritis. Cartil. 2019, 27, 1578–1589, doi:10.1016/j.joca.2019.06.011.

- Henrotin, Y.; Clutterbuck, A.L.; Allaway, D.; Lodwig, E.M.; Harris, P.; Mathy-Hartert, M.; Shakibaei, M.; Mobasheri, A. Biological actions of curcumin on articular chondrocytes. Cartil. 2010, 18, 141–149, doi:10.1016/j.joca.2009.10.002.

- Bu, S.Y.; Lerner, M.; Stoecker, B.J.; Boldrin, E.; Brackett, D.J.; Lucas, E.A.; Smith, B.J. Dried Plum Polyphenols Inhibit Osteoclastogenesis by Downregulating NFATc1 and Inflammatory Mediators. Tissue Int. 2008, 82, 475–488, doi:10.1007/s00223-008-9139-0.

- Mathy-Hartert, M.; Jacquemond-Collet, I.; Priem, F.; Sanchez, C.; Lambert, C.; Henrotin, Y. Curcumin inhibits pro-inflammatory mediators and metalloproteinase-3 production by chondrocytes. Res. 2009, 58, 899–908, doi:10.10007/s00011-009-0063-1.

- Umar, S.; Umar, K.; Sarwar, A.H.M.G.; Khan, A.; Ahmad, N.; Ahmad, S.; Katiyar, C.K.; Husain, S.A.; Khan, H.A. Boswellia serrata extract attenuates inflammatory mediators and oxidative stress in collagen induced arthritis. Phytomedicine 2014, 21, 847–856, doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2014.02.001.

- Wu, X.; Li, Z.; Yang, Z.; Zheng, C.; Jing, J.; Chen, Y.; Ye, X.; Lian, X.; Qiu, W.; Yang, F.; et al. Caffeic acid 3,4-dihydroxy-phenethyl ester suppresses receptor activator of NF-κB ligand-induced osteoclastogenesis and prevents ovariectomy-induced bone loss through inhibition of mitogen-activated protein kinase/activator protein 1 and Ca2+-nuclear fact. Bone Miner. Res. 2012, 27, 1298–1308, doi:10.1002/jbmr.1576.

- Crofford, L.J. Use of NSAIDs in treating patients with arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2013, 15, S2, doi:10.1186/ar4174.

- Benyamin, R.; Trescot, A.M.; Datta, S.; Buenaventura, R.; Adlaka, R.; Sehgal, N.; Glaser, S.E.; Vallejo, R. Opioid complications and side effects. Pain Physician 2008, 11, S105-120.

- Smith, C.; Patel, R.; Vannabouathong, C.; Sales, B.; Rabinovich, A.; McCormack, R.; Belzile, E.L.; Bhandari, M. Combined intra-articular injection of corticosteroid and hyaluronic acid reduces pain compared to hyaluronic acid alone in the treatment of knee osteoarthritis. Knee Surg. Sports Traumatol. Arthrosc. 2019, 27, 1974–1983, doi:10.1007/s00167-018-5071-7.

- Cao, P.; Li, Y.; Tang, Y.; Ding, C.; Hunter, D.J. Pharmacotherapy for knee osteoarthritis: Current and emerging therapies. Expert Opin. Pharmacother. 2020, 21, 1–13, doi:10.1080/14656566.2020.1732924.

- Wong, S.K.; Chin, K.-Y.; Ima-Nirwana, S. Berberine and musculoskeletal disorders: The therapeutic potential and underlying molecular mechanisms. Phytomedicine 2019, 152892, doi:10.1016/j.phymed.2019.152892.

- Liu, S.C.; Lee, H.P.; Hung, C.Y.; Tsai, C.H., Li, T.M., Tang, C.H. Berberine attenuates CCN2-induced IL-1β expression and prevents cartilage degradation in a rat model of osteoarthritis. Appl. Pharmacol. 2015, 289, 20–29, doi:10.1016/j.taap.2015.08.020.

- Zhou, Y.; Tao, H.; Li, Y.; Deng, M.; He, B.; Xia, S.; Zhang, C.; Liu, S. Berberine promotes proliferation of sodium nitroprusside-stimulated rat chondrocytes and osteoarthritic rat cartilage via Wnt/β-catenin pathway. J. Pharmacol. 2016, 789, 109–118, doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.07.027.

- Zhou, Y.; Liu, S.-Q.; Yu, L.; He, B.; Wu, S.-H.; Zhao, Q.; Xia, S.-Q.; Mei, H.-J. Berberine prevents nitric oxide-induced rat chondrocyte apoptosis and cartilage degeneration in a rat osteoarthritis model via AMPK and p38 MAPK signaling. Apoptosis 2015, 20, 1187–1199, doi:10.1007/s10495-015-1152-y.

- Zhou, Y. ; Liu, S.-Q.; Peng, H.; Yu, L.; He, B.; Zhao, Q. In vivo anti-apoptosis activity of novel berberine-loaded chitosan nanoparticles effectively ameliorates osteoarthritis. Immunopharmacol. 2015, 28, 34–43, doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2015.05.014.

- Zhou, Y.; Ming, J.; Deng, M.; Li, Y.; Li, B.; Li, J.; Ma, Y.; Chen, Z.; Liu, S. Berberine-mediated up-regulation of surfactant protein D facilitates cartilage repair by modulating immune responses via the inhibition of TLR4/NF-ĸB signaling. Res. 2020, 155, 104690, doi:10.1016/j.phrs.2020.104690.

- Lee, H.W.; Suh, J.H.; Kim, H.N.; Kim, A.Y.; Park, S.Y.; Shin, C.S.; Choi, J.-Y.; Kim, J.B. Berberine Promotes Osteoblast Differentiation by Runx2 Activation With p38 MAPK. Bone Miner. Res. 2008, 23, 1227–1237, doi:10.1359/jbmr.080325.

- Wei, P.; Jiao, L.; Qin, L.-P., Yan, F.; Han, T.; Zhang, Q.-Y. Effects of berberine on differentiation and bone resorption of osteoclasts derived from rat bone marrow cells. Chin. Integr. Med. 2009, 7, 342–348, doi:10.3736/jcim20090408.

- Hostetler, G.L.; Ralston, R.A.; Schwartz, S.J. Flavones: Food Sources, Bioavailability, Metabolism, and Bioactivity. Nutr. Int. Rev. J. 2017, 8, 423–435, doi:10.3945/an.116.012948.

- Salehi, B.; Venditti, A.; Sharifi-Rad, M.; Kregiel, D.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Durazzo, A.; Lucarini, M.; Santini, A.; Souto, E.B.; Novellino, E.; et al. The Therapeutic Potential of Apigenin. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 1305, doi:10.3390/ijms20061305.

- Shoara, R.; Hashempur, M.H.; Ashraf, A.; Salehi, A.; Dehshahri, S.; Habibagahi, Z. Efficacy and safety of topical Matricaria chamomilla (chamomile) oil for knee osteoarthritis: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Complement. Ther. Clin. Pract. 2015, 21, 181–187, doi:10.1016/j.ctcp.2015.06.003.

- Davidson, R.K.; Green, J.; Gardner, S.; Bao, Y.; Cassidy, A.; Clark, I.M. Identifying chondroprotective diet-derived bioactives and investigating their synergism. Rep. 2018, 8, 17173, doi:10.1038/s41598-018-35455-8.

- Park, J.S.; Kim, D.K.; Shin, H.-D.; Lee, H.J.; Jo, H.S.; Jeong, J.H.; Choi, Y.L.; Lee, C.J.; Hwang, S.-C. Apigenin Regulates Interleukin-1β-Induced Production of Matrix Metalloproteinase Both in the Knee Joint of Rat and in Primary Cultured Articular Chondrocytes. Ther. 2016, 24, 163–170, doi:10.4062/biomolther.2015.217.

- Melguizo-Rodríguez, L.; Manzano-Moreno, F.J.; Illescas-Montes, R.; Ramos-Torrecillas, J.; De luna-Bertos, E.; Ruiz, C.; Garcia-Martinez, O. Bone Protective Effect of Extra-Virgin Olive Oil Phenolic Compounds by Modulating Osteoblast Gene Expression. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1722, doi:10.3390/nu11081722.

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, C.; Zha, X.; Xu, Z.; Li, L.; Liu, Y.; Xu, L.; Cui, L.; Xu, D.; Zhu, B. Apigenin promotes osteogenic differentiation of human mesenchymal stem cells through JNK and p38 MAPK pathways. Cell. Biochem. 2015, 407, 41–50, doi:10.1007/s11010-015-2452-9.

- Riaz, A.; Rasul, A.; Hussain, G.; Zahoor, M.K.; Jabeen, F.; Subhani, Z.; Younis, T.; Ali, M.; Sarfraz, I.; Selamoglu, Z. Astragalin: A Bioactive Phytochemical with Potential Therapeutic Activities. Pharmacol. Sci. 2018, 1–15, doi:10.1155/2018/9794625.

- Liu, L.; Wang, D.; Qin, Y.; Xu, M.; Zhou, L.; Xu, W.; Liu, X.; Ye, L.; Yue, S.; Zheng, Q.; et al. Astragalin Promotes Osteoblastic Differentiation in MC3T3-E1 Cells and Bone Formation in vivo. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 228, doi:10.3389/fendo.2019.00228.

- Ma, Z.; Piao, T.; Wang, Y.; Liu, J. Astragalin inhibits IL-1β-induced inflammatory mediators production in human osteoarthritis chondrocyte by inhibiting NF-κB and MAPK activation. Immunopharmacol. 2015, 25, 83–87, doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2015.01.018.

- Jia, Q.; Wang, T.; Wang, X.; Xu, H.; Liu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Shi, Q.; Liang, Q. Astragalin Suppresses Inflammatory Responses and Bone Destruction in Mice With Collagen-Induced Arthritis and in Human Fibroblast-Like Synoviocytes. Pharmacol. 2019, 10, 94, doi:10.3389/fphar.2019.00094.

- Sowndhararajan, K.; Deepa, P.; Kim, M.; Park, S.J.; Kim, S. Baicalein as a potent neuroprotective agent: A review. Pharmacother. 2017, 95, 1021–1032, doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2017.08.135.

- Bie, B.; Sun, J.; Guo, Y.; Li, J.; Jiang, W.; Yang, J.; Huang, C.; Li, Z. Baicalein: A review of its anti-cancer effects and mechanisms in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Pharmacother. 2017, 93, 1285–1291, doi:10.1016/j.biopha.2017.07.068.

- Zhang, X.; Zhu, Y.; Chen, X.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, Y.; Wang, H.; Liu, Y.; Xiao, L. Baicalein ameliorates inflammatory-related apoptotic and catabolic phenotypes in human chondrocytes. Immunopharmacol. 2014, 21, 301–308, doi:10.1016/j.intimp.2014.05.006.

- Li, Y.; Wang, J.; Song, X.; Bai, H.; Ma, T.; Zhang, Z.; Li, X.; Jiang, R.; Wang, G.; Fan, X.; et al. Effects of baicalein on IL-1β-induced inflammation and apoptosis in rat articular chondrocytes. Oncotarget 2017, 8, 90781–90795, doi:10.18632/oncotarget.21796.

- Chen, W.-P.; Xiong, Y.; Hu, P.-F.; Bao, J.-P.; Wu, L.-D. Baicalein Inhibits MMPs Expression via a MAPK-Dependent Mechanism in Chondrocytes. Physiol. Biochem. 2015, 36, 325–333, doi:10.1159/000374075.

- Kim, M.H.; Ryu, S.Y.; Bae, M.A.; Choi, J.-S.; Min, Y.K.; Kim, S.H. Baicalein inhibits osteoclast differentiation and induces mature osteoclast apoptosis. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2008, 46, 3375–3382, doi:10.1016/j.fct.2008.08.016.

- Li, S.; Tang, J.-J.; Chen, J.; Zhang, P.; Wang, T.; Chen, T.-Y.; Yan, B.; Huang, B.; Wang, L.; Huang, M.-J.; et al. Regulation of bone formation by baicalein via the mTORC1 pathway. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2015, 9, 5169–5183, doi:2147/DDDT.S81578.

- Samarghandian, S.; Farkhondeh, T.; Azimi-Nezhad, M. Protective Effects of Chrysin Against Drugs and Toxic Agents. Dose Response 2017, 15, 1559325817711782, doi:10.1177/1559325817711782.

- Zheng, W.; Tao, Z.; Cai, L.; Chen, C.; Zhang, C.; Wang, Q.; Ying, X.; Hu, W.; Chen, H. Chrysin Attenuates IL-1β-Induced Expression of Inflammatory Mediators by Suppressing NF-κB in Human Osteoarthritis Chondrocytes. Inflammation 2017, 40, 1143–1154, doi:10.1007/s10753-017-0558-9.

- Zhang, C.; Yu, W.; Huang, C.; Ding, Q.; Liang, C.; Wang, L.; Hou, Z.; Zhang, Z. Chrysin protects human osteoarthritis chondrocytes by inhibiting inflammatory mediator expression via HMGB1 suppression. Med. Rep. 2018, 19, 1222–1229, doi:10.3892/mmr.2018.9724.

- Zeng, W.; Yan, Y.; Zhang, F.; Zhang, C.; Liang, W. Chrysin promotes osteogenic differentiation via ERK/MAPK activation. Protein Cell 2013, 4, 539–547.

- Menon, A.H.; Soundarya, S.P.; Sanjay, V.; Chandran, S.V.; Balagangadharan, K.; Selvamurugan, N. Sustained release of chrysin from chitosan-based scaffolds promotes mesenchymal stem cell proliferation and osteoblast differentiation. Polym. 2018, 195, 356–367, doi:10.1016/ j.carbpol.2018.04.115.

- Mukund, V.; Mukund, D.; Sharma, V.; Mannarapu, M.; Alam, A. Genistein: Its role in metabolic diseases and cancer. Rev. Oncol. Hematol. 2017, 119, 13–22, doi:10.1016/j.critrevonc.2017.09.004.

- Oliviero, F.; Scanu, A.; Zamudio-Cuevas, Y.; Punzi, L.; Spinella, P. Anti-inflammatory effects of polyphenols in arthritis. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 1653–1659, doi:10.1002/jsfa.8664.

- Spagnuolo, C.; Moccia, S.; Russo, G.L. Anti-inflammatory effects of flavonoids in neurodegenerative disorders. J. Med. Chem. 2018, 153, 105–115, doi:10.1016/j.ejmech.2017.09.001.

- Claassen, H.; Briese, V.; Manapov, F.; Nebe, B.; Schünke, M.; Kurz, B. The phytoestrogens daidzein and genistein enhance the insulin-stimulated sulfate uptake in articular chondrocytes. Cell Tissue Res. 2008, 333, 71–79, doi:10.1007/ s00441-008-0616-6.

- Tanamas, S.K.; Wijethilake, P.; Wluka, A.E.; Davies-Tuck, M.L.; Urquhart, D.M.; Wang, Y.; Cicuttini, F.M. Sex hormones and structural changes in osteoarthritis: A systematic review. Maturitas 2011, 69, 141–156, doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.03.019.

- Thangavel, P.; Puga-Olguín, A.; Rodríguez-Landa, J.F.; Zepeda, R.C. Genistein as Potential Therapeutic Candidate for Menopausal Symptoms and Other Related Diseases. Molecules 2019, 24, 3892, doi:3390/molecules24213892.

- Liu, F.-C.; Wang, C.-C.; Lu, J.-W.; Lee, C.-H.; Chen, S.-C.; Ho, Y.-J.; Peng, Y-J. Chondroprotective Effects of Genistein against Osteoarthritis Induced Joint Inflammation. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1180, doi:3390/nu11051180.

- Yuan, J.; Ding, W.; Wu, N.; Jiang, S.; Li, W. Protective Effect of Genistein on Condylar Cartilage through Downregulating NF-κB Expression in Experimentally Created Osteoarthritis Rats. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 3, 1–6, doi:10.1155/2019/2629791.

- Ming, L.-G.; Chen, K.-M.; Xian, C.J. Functions and action mechanisms of flavonoids genistein and icariin in regulating bone remodeling. Cell. Physiol. 2013, 228, 513–521, doi:10.1002/jcp.24158.

- Kim, M.; Lim, J.; Lee, J.-H.; Lee, K.-M.; Kim, S.; Park, K.W.; Nho, C.W.; Cho, Y.S. Understanding the functional role of genistein in the bone differentiation in mouse osteoblastic cell line MC3T3-E1 by RNA-seq analysis. Rep. 2018, 8, 3257, doi:10.1038/s41598-018-21601-9.

- Cepeda, S.B.; Sandoval, M.J.; Crescitelli, M.C.; Rauschemberger, M.B.; Massheimer, V.L. The isoflavone genistein enhances osteoblastogenesis: Signaling pathways involved. Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 76, 99–110, doi:10.1007/s13105-019-00722-3.

- Yamaguchi, M.; Levy, R.M. Combination of alendronate and genistein synergistically suppresses osteoclastic differentiation of RAW267.4 cells in vitro. Exp. Ther. Med. 2017, 14, 1769–1774, doi:10.3892/etm.2017.4695.