| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Michael Rigby | + 2105 word(s) | 2105 | 2021-02-23 04:38:27 | | | |

| 2 | Bruce Ren | -21 word(s) | 2084 | 2021-03-08 03:09:54 | | |

Video Upload Options

Robert Anderson has made a huge contribution to almost all aspects of morphology and under-standing of congenital cardiac malformations, none more so than the group of anomalies that many of those in the practice of paediatric cardiology and adult congenital heart disease now call ‘Atrioventricular Septal Defect’ (AVSD). In 1982, with Anton Becker working in Amsterdam, their hallmark ‘What’s in a name?’ editorial was published in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardio-vascular Surgery. At that time most described the group of lesions as ‘atrioventricular canal mal-formation’ or ‘endocardial cushion defect’. Perhaps more significantly, the so-called ostium pri-mum defect was thought to represent a partial variant. It was also universally thought, at that time, that the left atrioventricular valve was no more than a mitral valve with a cleft in the aortic leaflet. In addition to this, lesions such as isolated cleft of the mitral valve, large ventricular septal defects opening to the inlet of the right and hearts with straddling or overriding tricuspid valve were variations of the atrioventricular canal malformation. Anderson and Becker emphasised the differences between the atrioventricular junction in the normal heart and those with a common junction for which they recommended the generic name, ‘atrioventricular septal defect’.

1. Introduction

Robert Anderson has made a huge contribution to almost all aspects of morphology and understanding of congenital cardiac malformations, none more so than the group of anomalies that many of those in the practice of paediatric cardiology and adult congenital heart disease now call ‘Atrioventricular Septal Defect’ (AVSD). In 1982, with Anton Becker working in Amsterdam, their hallmark ‘What’s in a name?’ editorial was published in the Journal of Thoracic and Cardiovascular Surgery [1].

Prior to that groundbreaking publication, it was already recognised that a group of malformations had comparable morphology comprising abnormal atrioventricular valves. Blieden and colleagues [2] had previously described disproportion between the inlet and outlet dimensions of the ventricles, readily demonstrated by the left ventricular ‘goose-neck’ on angiography, as the key to diagnosis. At that stage most described the group of lesions as ‘atrioventricular canal malformation’ or ‘endocardial cushion defect’ [3][4]. Perhaps more significantly, the so-called ostium primum defect was thought to represent a partial variant. It was also universally thought, at that time, that the left atrioventricular valve was no more than a mitral valve with a cleft in the aortic leaflet. In addition to this, lesions such as isolated cleft of the mitral valve, large ventricular septal defects opening to the inlet of the right and hearts with straddling or overriding tricuspid valve were considered variations of the atrioventricular canal malformation.

There were two extremely important events contributing to the breakthrough in understanding. The first was when Anderson and Becker, working with heart specimens in Amsterdam, stripped away completely from the atrioventricular junction, the leaflets of the atrioventricular valves. Having removed the valve leaflets, it was realised that in any individual heart with this group of anomalies, it was impossible to know whether, initially, the specimen had represented a so-called ‘partial’, ‘intermediate’ or ‘complete’ example of the anatomy, because each of the hearts had a common atrioventricular junction completely different from the normal heart. The second important event was when cardiologists, using their newly acquired skills in cross-sectional echocardiography, were able to produce exquisite moving images of these hearts, representing cross-sectional anatomic sections. I recall Bob Anderson being ‘blown away’ by what he was seeing at our regular weekly meetings and immediately our understanding began to reach completion. With morphological sections of the heart [5], he simulated echocardiographic sections in four chamber and short axis of the atrioventricular junction, confirming, at a stroke, these provided almost all of the information for accurate diagnosis apart from demonstrating the ventricular outflows.

By coincidence, in 1982 we were both guests of the Brazilian Society of Pediatric Cardiology in Porto Alegre around the time of publication. During this, my first visit to South America (Figure 1) it was no coincidence that some of the academic sessions revolved around the potentially controversial topic of AVSD, the subject of the ‘What’s in a name’ publication. Anderson and Becker had advocated dismissing the terms ‘endocardial cushion defect’ and ‘atrioventricular canal defect’ on the basis they were morphologically unsound and inaccurate despite them being in common usage. By that time, I had found their arguments persuasive and, using the ‘new’ nomenclature, together we demonstrated heart specimens and moving echocardiographic images of the heart painstakingly recorded and edited onto high quality video tape. The presentations and recommendations were received enthusiastically by the large international faculty and many delegates. So began a new era of understanding, crucial to improvements in surgical outcome. However, although it was the intention of Becker and Anderson to provide a precise and accurate way of describing hearts with AVSD, the term has continued to be used imprecisely by many cardiologists and surgeons, as I will outline later.

Figure 1. Invited faculty, Brazilian Congress of Pediatric Cardiology, Porto Alegre, 1982.

2. Consideration of the Atrioventricular Junction and Valve Leaflets

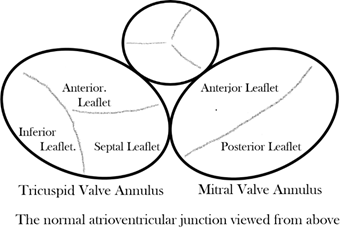

Considering first the normal atrioventricular junction [6], it is divided into discrete right and left components that surround the orifices of the mitral and tricuspid valves, respectively (Figure 2). The two junctions are themselves contiguous only over a very short area, which is that of the muscular atrioventricular septum anterior, and superior to this short area, the subaortic outflow tract of the left ventricle interposes between the mitral valve and the muscular ventricular septum and the fibrous membranous septum. At all other points around the atrioventricular injunctions, the fibrofatty tissue of the atrioventricular grooves interposes between atrial and ventricular myocardium and becomes contiguous with the fibrous leaflets of mitral and tricuspid valves while the aortic valve is wedged anteriorly between the mitral and tricuspid valves.

Figure 2. Drawing of the normal atrioventricular junction.

In essence, Anderson and Becker had proposed the term ‘atrioventricular septal defect’ as a generic name for a group of anomalies characterised by absence of atrioventricular septal structures and consequently possessing a common atrioventricular junction guarded by a common atrioventricular valve and therefore completely different from the atrioventricular junction of the normal heart[7]. There is not only a grossly abnormal atrioventricular junction morphology but also of necessity an abnormally positioned conduction axis as well as the subaortic outflow no longer being able to interpose between the left and right sides of the junction.

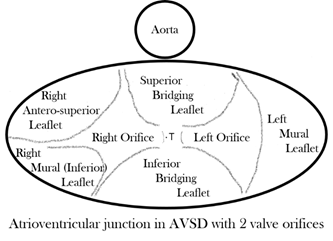

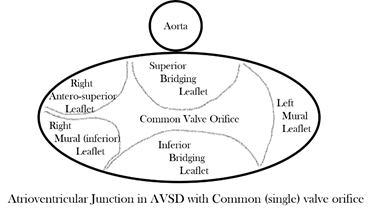

In almost every form, the common atrioventricular valve is composed of five leaflets of which only the superior and inferior bridging leaflets are found within both the left and right ventricles, whereas the left mural leaflet is confined to the left ventricle and the right (inferior) mural and right anterosuperior leaflets are located inferiorly and antero-superiorly, respectively, in the right ventricle. The zone of apposition of the inferior and superior bridging leaflets is the most frequent site of valve insufficiency. This common valve will have a single (‘common’) orifice or will be divided into two orifices by a tongue of valve tissue joining the bridging leaflets; this provides the basis for a broad classification of all cases (Figure 3a,b). Irrespective of common or separate orifices the left ventricular component of the common valve has a trileaflet arrangement that cannot be compared with the normal mitral valve, an appellation that should be avoided. The right ventricular component of the common valve similarly should not be called ‘tricuspid’. It is also important to be aware that ‘AVSD’ on its own is not a diagnosis and should not be used alone to describe any of the various forms of this group of anomalies because it lacks any specificity whatsoever.

(a)

(b)

Figure 3. (a) Drawing of the atrioventricular junction in Atrioventricular Septal Defect (AVSD) with two valve orifices. (b) Drawing of the atrioventricular junction in AVSD with common valve orifice.

With two valve orifices the most frequent form is the isolated primum defect, which is also commonly described as ‘partial AVSD’, although there is nothing partial about the common atrioventricular junction, which is just as complete as that seen in patients with common valve orifice. Other variations include an isolated interventricular defect or combined primum interatrial defect and interventricular component; both forms can also be described as ‘intermediate’, but qualifying additional description is required in diagnosis to distinguish the two forms. Rarely are completely intact septal structures found, an AVSD without interatrial or interventricular communication. With common orifice the main variation is found in the degree of bridging of the superior bridging leaflet, but there is almost always an interatrial and interventricular communication. Whatever the type of AVSD, the left ventricular outflow is sometimes longer than that of the normal heart [8], and the value of the inlet/outlet dimensions ratio was significantly less in hearts with atrioventricular septal defects, with p < 0.001 in Table III of that publication. So, it seems to me that it could indeed be a diagnostic criterion on its own.

3. Variations from Usual Forms of AVSD

Quite independent of these various types, associated anomalies can include left or right ventricular inflow obstruction, dual orifice left ventricular atrioventricular valve leaflets, atrioventricular valve regurgitation, left or right ventricular outflow tract obstruction in various forms, and right or left ventricular hypoplasia (‘ventricular imbalance’). Left ventricular outflow obstruction can be particularly complex. The subaortic outflow is frequently elongated and relatively narrow in all forms of AVSD. The causes of obstruction include anomalous tissue tags, anomalous chords to the ventricular septum, discrete fibromuscular stenosis and tunnel-like narrowing. Another variation to be aware of is double outlet right atrium, in which inevitably blood flows directly from right atrium to left ventricle, causing unexplained systemic arterial desaturation. There is also a well-recognised association of AVSD with Trisomy 21, atrial isomerism, total anomalous pulmonary venous connection and Tetralogy of Fallot and, rarely, even with common arterial trunk.

The key to the diagnosis of AVSD and, to a major extent, appropriate and effective surgical management lies in the structure of the atrioventricular valve leaflets found in the left ventricle [9][10]. When the left atrioventricular component of the common junction is considered in isolation, the mural leaflet forms less than one-third of the circumference of the orifice, the remainder being formed of components of the superior and inferior bridging leaflets, which together form a zone of apposition that some still and incorrectly describe as ‘a cleft’. Even if a surgeon were to suture together completely this zone of apposition, such a manoeuvre would not restore the morphology to that of a normal mitral valve. There is not complete agreement as to whether or not at the time of operation the surgeon should suture together, partially or completely, the zone of apposition, particularly in the absence of preoperative valve insufficiency.

There is a potentially complicating aspect when the left ventricular valve leaflets lack the usual morphology found in an AVSD, and this also has major surgical significance [11][12]. The classical distortion is found in parachute malformations. In such cases all the valve chords attach to a single papillary muscle, usually because the mural leaflet is extremely small or absent. The valve orifice is then represented only by the zone of apposition between the bridging leaflets, and the key point of surgical significance is it cannot be sutured, even in the presence of significant valve insufficiency, because stenosis will almost inevitably be the outcome. However, the parachute malformation of the left AV valve in AVSD may not be caused by an absent mural leaflet. It could be the reverse in that, if there is a single papillary muscle, then the mural leaflet is by necessity absent. In the study by Oosthoek PW et al. [13], the anomaly of the papillary muscles was considered the primary event leading to parachute valve. Other deviations from the usual valve morphology include leaflet dysplasia, a small or miniaturized orifice, short superior bridging leaflet, extremely short valve chords or dual orifice produced by an anomalous bridge of valve tissue between any two of the leaflets.

It is important briefly to discuss a rare form of deficient atrioventricular septation with separate left and right atrioventricular junctions. The patients with deficiency of the fibrous atrioventricular septum, although properly described as atrioventricular septal defects, do not have a common atrioventricular junction. It was the view of Anderson that it was more convenient to describe them as ‘Gerbode’ defects while recognising their affinity with hearts with perimembranous VSD combined with the potential for ventriculo-atrial shunting because of a deficiency in the commissure between the septal and anterior leaflets of the tricuspid valve.

References

- Becher, A.E.; Anderson, R.H. Atrioventricular septal defects. What’s in a name? J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1982, 83, 461–469.

- Blieden, L.C.; Randall, P.A.; Castaneda, A.R.; et al. The ‘goose neck’ of the endocardial cushion defect: Anatomical basis. Chest 1974, 65, 13–17.

- Rastelli, G.; Kirklin, J.W.; Titus, J.L. Anatomic observations on complete form of persistent common atrioventricular canal with special reference to atrioventricular valves. Mayo Clin. Proc. 1966, 41, 296–308.

- Van Mierop, L.H.S.; Alley, R.D.; Kausel, H.W.; et al. The anatomy and embryology of endocardial cushion defects. J. Thorac. Cardi-ovasc. Surg. 1962, 43, 71–83.

- Smallhorn, J.F.; Tommasini, G., Anderson, R.H.; et al. Assessment of atrioventricular septal defects by two-dimensional echocar-diography. Br. Heart J. 1982, 30, 446–457.

- Anderson, R.H.; Ho, S.Y.; Becker, A.E. Anatomy of the human atrioventricular junctions revisited. Anat. Rec. Adv. Integr. Anat. Evol. Biol. 2000, 260, 81–91, doi:10.1002/1097-0185(20000901)260:13.0.co;2-3.

- Silverman, N.H.; Zuberbuhler, J.R.; Anderson, R.H. Atrioventricular septal defects: Cross-sectional echocardiographic and mor-phologic comparisons. Int. J. cardiol. 1986, 13, 309–331.

- Penkoske, P.A.; Neches, W.H., Anderson, R.H.; et al. Further observations on the morphology of atrioventricular septal de-fects. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1985, 90, 611–622.

- Anderson, R.H.; Ho, S.Y.; Falcao, S.; Daliento, L.; Rigby, M.L. The diagnostic features of atrioventricular septal defect with common atrioventricular junction. Cardiol. Young 1998, 8, 33–49, doi:10.1017/s1047951100004613.

- Akiba, T.; Becker, A.E.; Neirotti, R.; Tatsuno, K. Valve morphology in complete atrioventricular septal defect: Variability rel-evant to operation. Ann. Thorac. Surg. 1993, 56, 295–299, doi:10.1016/0003-4975(93)91163-h.

- Piccoli, G.P.; Ho, S.Y.; Wilkinson, J.L.; Macartney, F.J.; Gerlis, L.M.; Anderson, R.H. Left-sided obstructive lesions in atrioven-tricular septal defects. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1982, 83, 453–460, doi:10.1016/s0022-5223(19)37284-8.

- Ebels, T.; Anderson, R.H.; Devine, W.A.; et al. Anomalies of the left atrioventricular valve and related ventricular septal morphology in atrioventricular septal defects. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1990, 99, 299–307.

- Oosthoek, P.W.; Wenink, A.C.; Macedo, A.J.; Groot, A.C.G.-D. The parachute-like asymmetric mitral valve and its two pa-pillary muscles. J. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 1997, 114, 9–15, doi:10.1016/s0022-5223(97)70111-9.