| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Chris Kapelios | + 2281 word(s) | 2281 | 2021-02-23 04:07:40 | | | |

| 2 | Bruce Ren | -21 word(s) | 2260 | 2021-03-05 05:19:41 | | | | |

| 3 | Bruce Ren | Meta information modification | 2260 | 2021-03-05 05:24:42 | | |

Video Upload Options

Increased cardiac fat depots are metabolically active tissues having a pronounced pro-inflammatory nature. Increasing evidence supports a potential role of cardiac adiposity as a determinant of the substrate of atrial fibrillation and ventricular arrhythmias. The underlying mechanism appears to be multifactorial with local inflammation, fibrosis, adipocyte infiltration, electrical remodeling, autonomic nervous system modulation, oxidative stress and gene expression playing interrelating roles. Current imaging modalities, such as echocardiography, computed to-mography and cardiac magnetic resonance, have provided valuable insight into the relationship between cardiac adiposity and arrhythmogenesis, in order to better understand the pathophysi-ology and improve risk prediction of the patients, over the presence of obesity and traditional risk factors.

1. Cardiac adiposity pathophysiology

Overwhelming evidence supports the idea that adipose tissue acts as an endocrine organ having a significant impact on cardiovascular function [1]. Obesity is associated with adipose tissue dysfunction including increased proinflammatory and decreased anti-inflammatory factors secretion, thus contributing to insulin resistance, glucose intolerance, hypertension and abnormal lipid metabolism that are often seen in obese people [1,2]. These alterations affect the heart and vessels resulting in an increase in cardiovascular (CV) events. This risk is significantly linked to the distribution of fat rather than body mass index (BMI) or total adiposity, being much higher in the presence of visceral adipose tissue (VAT) and increased ectopic fat accumulation in normally lean organs, such as the liver, heart and skeletal muscles [2][3][4].

Increased cardiac fat depots are metabolically active tissues having a pronounced pro-inflammatory nature, which is enhanced in obesity and type-2 diabetes [3]. Ectopic cardiac fat may be located pericardially (the adipose tissue surrounds the parietal pericardium), epicardially (adipose tissue between the myocardium and visceral pericardium) and intramyocardially, termed as cardiac steatosis [5][6]. Physiologically, epicardial adipose tissue (EAT) has a cardioprotective role on the heart, regulating levels of pro-inflammatory cytokines, stimulating the production of nitric oxide, reducing oxidative stress and protecting coronary arteries against mechanical strain [1][3]. It is currently accepted that myocardial triglyceride accumulation is probably inert [7]. Myocardial energy demands are mainly covered by the oxidation of circulating plasma free fatty acids [8]. However, when excessive free fatty acid delivery is present, such as in obesity or insulin-resistant states, the process exceeds the myocardial oxidative capacity, resulting in myocardial lipid overstorage and lipotoxicity that increase production of reactive oxygen species and cause apoptosis [9].

Currently, it is supported that an increase in EAT volume occurs in response to chronic metabolic challenges of the heart, resulting in cytokine upregulation and increased fatty acid oxidation [10]. Ectopic EAT has been suggested to play a significant role in promoting coronary artery atherosclerosis, arrhythmogenesis and heart failure (HF), through dysregulation of various types of adipokines (adiponectin, leptin, tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-a), interleukin 6 (IL-6), monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 (MCP-1)) and via increased exosomal miRNAs synthesis [11]. Given that EAT surrounds the myocardium and coronary arteries in the absence of a separating fascia, the ectopic EAT-driven proinflammatory and profibrotic cytokines may diffuse to underlying tissues in a paracrine-dependent manner, contributing to a low grade inflammatory and profibrotic state in the myocardium and vasculature. A heightened state of inflammation in pericoronary adipocytes has been demonstrated in many studies [12].

Imaging modalities, such as echocardiography but mostly computed tomography (CT) and cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) are widely used for detailed fat visualization of cardiac fat deposits. The aim of this review is to provide an overview of the possible additive utility of imaging modalities in screening cardiac adiposity and predicting future arrhythmic risk in patients with increased cardiac fatty depots, along with discussion of underlying disease mechanisms.

2. Non-invasive Imaging Assessment of Cardiac Fat

EAT/PAT volume and thickness can be assessed non-invasively by echocardiography, multidetector CT and CMR, with the two latter able to provide a three-dimensional volumetric quantification (Table 1) [13]. Although EAT and PAT have distinct embryological characteristics, and probably differential clinical effects, there is heterogeneity in the nomenclature used among imaging studies regarding the subgroups of cardiac fat depots, with the term pericardial adipose tissue (PAT) often used to refer to all adipose tissue located epicardially and paracardially (superficial to the pericardium) [14].

Table 1. Cardiac adiposity screening by imaging modalities. Advantages, limitations and clinical implications apart from arrhythmias.

|

|

|||

|

Advantages |

• EAT/PAT assessment: - volumetric technique - 3-dimensional EAT measurement - high reproducibility - better spatial resolution than CMR - EAT assessment on contrast and non-contrast scans

• Additional information: - relation of EAT radiodensity with metabolic processes - calcification of the coronary arteries - coronary artery stenosis - anatomical and metabolic data with PET/CT |

• EAT/PAT assessment: - volumetric technique - 3-dimensional EAT measurement - high reproducibility - no radiation exposure - no use of contrast agents

• Myocardial fatty infiltration assessment by: - 1H-MRS - multiecho Dixon methods

• Additional information: - biventricular function assessment - LV mass - LA volume - fibrosis by LGE |

• EAT/PAT thickness assessment: - relatively inexpensive - widely available - no radiation exposure

• Additional information: - biventricular function assessment - LV mass - LA volume

|

|

Limitations |

- radiation exposure - nephrotoxicity |

• CMR: - lack of availability/expertise - high cost - marked obesity - claustrophobia - often the pericardium not clearly seen on inferior slices of CMR scans - impossible to scan CMR-unsafe devices (metallic clips, pacemakers, defibrillators)

• 1H-MRS - lack of availability/expertise - high cost - contamination from EAT/PΑΤ

|

- no volumetric EAT estimation - difficulties in distinguishing the EAT from PAT or pericardial effusion - dependent on operator’s experience |

|

Clinical implications |

• EAT/PAT is associated with - adverse CV outcome - CAD - coronary artery calcification |

• EAT/PAT is associated with - presence/severity of CAD - impaired LV systolic function - myocardial fibrosis

• Myocardial fatty infiltration associations - diastolic dysfunction - dilated cardiomyopathy - ARVC - myocardial fibrosis |

• EAT thickness is associated with: - presence/severity of CAD - LV hypertrophy - diastolic dysfunction - HFpEF/HFmrEF - metabolic syndrome - carotid atherosclerosis - Framingham risk score

|

Abbreviations: ARVC: arrhythmogenic right ventricle cardiomyopathy; CAD: coronary artery disease; CMR: cardiovascular magnetic resonance; CT: computed tomography; CV: cardiovascular; EAT: epicardial adipose tissue; 1H-MRS: hydrogen proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy; HFmrEF: heart failure with mid-range ejection fraction; HFpEF: heart failure with preserved ejection fraction; LA: left atrium; LGE: late gadolinium enhancement; LV: left ventricle; PAT: pericardial adipose tissue; PET: positron emission tomography.

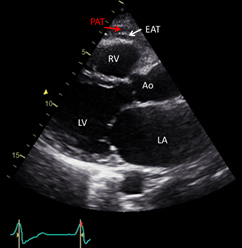

Echocardiography, is a safe, easily reproducible method, which can measure fat thickness in front of the free right ventricle wall, in the parasternal long and short axis views (Figure 1) . Difficulties in calculating the whole EAT volume and distinguishing the EAT from PAT or pericardial effusion, are the main disadvantages of the method. Α cut-off value >5 mm for EAT thickness has been correlated with increased CV risk.

Figure 1. Transthoracic echocardiographic view showing EAT and PAT as echo-lucent areas in front of the RV free wall. EAT is pointed by a white arrow and PAT by a red arrow. Ao: aorta; EAT: epicardial adipose tissue; LA: left atrium; LV: left ventricle; PAT: pericardial tissue; RV: right ventricle.

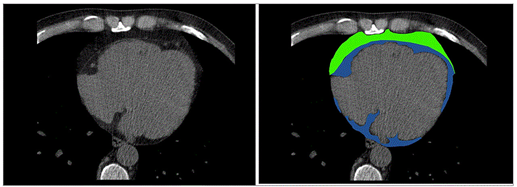

Cardiac CT has been increasingly used for assessment of EAT/PAT (Figure 2). A radiodensity threshold, of -190 to -30 Hounsfield (HU) units on non-contrast scans and -190 to -3 HU on contrast enhanced CT scans is accurate and reproducible for diagnosis and quantification of EAT volume. In addition to EAT volume, quantification of CT-derived fat attenuation has been correlated with local and systemic inflammatory markers, reflecting unfavorable metabolic activity. In the presence of increased inflammation, higher CT attenuation of EAT is expected. Furthermore, CT can provide information about inflammation of EAT tissue in conjunction with positron emission tomography (PET). Concurrently, CT provides information about calcification of the coronary arteries and coronary stenoses while its main disadvantage is the exposure to ionizing radiation and nephrotoxicity induced from the contrast material. Furthermore, CT can evaluate arterial inflammation in combination with positron emission tomography (PET/CT). In two population-based studies using CT, the Framingham Heart study and the Multi-Ethnic Study of Atherosclerosis, EAT/PAT has been identified as an independent risk predictor for CV disease in the general population. In keeping with these results, other studies demonstrated that CT-derived EAT/PAT was significantly correlated with high atherosclerotic burden of underlying coronary arteries, incident myocardial infarction and atrial fibrillation (AF) development .

Figure 2. Cardiac Computed Tomography: EAT (depicted in blue) is located between the myocardium and visceral pericardium, PAT (depicted in green) is located adherent and external to the parietal pericardium. EAT: epicardial adipose tissue; PAT: pericardial tissue. de Wit-Verheggen VHW, et al. Cardiovasc Diabetol. 2020;19:129, under Creative Commons license 4.0.

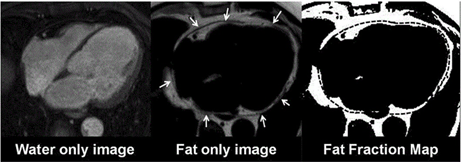

CMR is a noninvasive imaging modality without radiation, able to provide biventricular function assessment, and both tissue characterization and highly reproducible, three-dimensional EAT measurements. Assessment of EAT volume does not require the use of gadolinium-based contrast agents and is usually quantified by cine bright-blood steady-state free-precession (SSFP) sequences. Currently, hydrogen proton (1 H) magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) is considered the clinical reference standard for quantifying myocardial triglyceride content, without the need for contrast agents or radionuclides. Spectroscopy can distinguish between multiple myocardial triglycerides, water and creatine based on their different resonance frequencies during 1H-MRS. The spectroscopic volume of interest is usually positioned within the interventricular septum and the spectroscopic signals are acquired with cardiac triggering at end systole. Myocardial steatosis is quantified as the myocardial triglyceride content relative to water or creatine. In addition, newer CMR techniques such as multiecho Dixon-like methods that rapidly obtain fat and water separated images from the region of interest, in a single breath-hold, avoiding contamination from EAT, are also useful tools for this purpose [28,30]. Using the in-phase/out-of-phase cycling of fat and water, water only and fat only images can be created (Figure 3). This method can also be combined with a variety of sequence types (spin echo, gradient echo, SSFP sequences) and weightings (T1, T2 and proton density). Myocardial fatty infiltration has been linked with diastolic dysfunction, dilated cardiomyopathy and arrhythmogenic right ventricle cardiomyopathy (ARVC). Concurrently, EAT/PAT, as assessed by CMR, has been associated with the extent and severity of coronary atherosclerosis, impaired left ventricle (LV) systolic function and myocardial fibrosis in CMR studies.

Figure 3. CMR Dixon images. A: Fat only image. B: Fat only Image with the epicardial outlines (arrows). C: Segmented fat voxels with the transferred region of interest. CM: cardiac magnetic resonance. Kropidlowski C, et al. Int J Cardiol Heart Vasc. 2020;27:100477, under Creative Commons license 4.0.

The advantages, limitations and clinical implications of different screening modalities in imaging cardiac adiposity are summarized in Table 1.[38]

3. Pathophysiological Mechanisms of AF

AF is the most common clinically relevant arrhythmia. The mechanisms of AF are complex and multifactorial, involving an interaction between initiating triggers, an abnormal atrial substrate and a modulator such as a vagal or sympathetic stimulation [39][40][41]. The triggering of premature atrial contractions by beats that arise especially from one or more pulmonary veins and less frequently from other parts of the atria, may initiate AF while the repetitive firing of these focal triggers may contribute to the perpetuation of the arrhythmia [41][42]. The PVs play an important role in the arrhythmogenesis of AF through the mechanism of automaticity, triggered activity and reentry. Once the arrhythmia has been triggered, different theories, including the multiple wavelet hypothesis and rotors model, have been suggested to explain the maintenance of AF [43][44]. In the first theory, multiple wavelets randomly propagate through the atrial tissue in different directions, detected as complex fractionated electrograms by mapping catheters. In the second theory, the AF is contributed to reentrant electrical rotors, which are identified as wavelets with rotational activity around a structural or functional center detected by spectral analysis of high-frequency sites via intracardiac mapping catheters.

Increasing evidence supports the role of the autonomic nervous system in the initiation and maintenance of AF through the ganglionic plexuses commonly located on the left atrium in close proximity with epicardial fat pads[45]. Both parasympathetic and sympathetic stimulation enhance propensity to AF, the first by shortening the effective refractory period, whereas the second facilitating induction of AF and automaticity in focal discharge. The role of ablation of ganglionated plexi as an adjunctive procedure in the treatment of AF remains to be determined[46].

The development of AF induces a slow but progressive process of atrial substrate abnormalities involving electrical and structural alterations [47]. These changes facilitate electrical reentrant circuits or triggers, which, in turn, increase the propensity for the development and maintenance of the arrhythmia. Electrical remodeling includes shortening of the atrial action potential duration and increased dispersion of refractoriness largely due to downregulation of the l-type Ca2+ inward current and upregulation of inward rectifier K+ currents, while heterogeneity in the distribution of intercellular gap junction proteins such a connexin 40 or 43 has been linked with slower conduction velocity, which favors reentry [48][49][50][51]. Over time, the presence of AF also leads to structural changes including, hypocontractility, fatty infiltration, inflammation, atrial dilatation and stretch-induced atrial fibrosis which is the hallmark of structural remodeling of AF and is considered especially important substrate for AF perpetuation [52][53][54].

Experimental and clinical data indicate that inflammation is particularly involved in the initiation and maintenance of AF and conversely AF can further promote inflammation [55][56]. Although, the precise mechanistic links remain unclear, several effects of inflammation seem to be mediated by oxidative stress [57]. Various inflammatory biomarkers including C-reactive protein (CRP), IL-6, TNF-α, and MCP-1 are associated with AF risk [57][58]. It has been suggested that TNF-α, IL-2 and platelet‐derived growth factor can provoke abnormal triggering in PVs and shortening of atrial action potential duration through regulation of calcium homeostasis, as well as induce atrial fibrosis, connexin dysregulation and apoptosis leading to increased conduction heterogeneity. However, their clinical utility in guiding AF management is not well established .

References

- Rodríguez, A.; Becerril, S.; Hernández-Pardos, A.W.; Frühbeck, G. Adipose tissue depot differences in adipokines and effects on skeletal and cardiac muscle. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2020, 52, 1–8.

- Piché, M.E.; Tchernof, A.; Després, J.P. Obesity phenotypes, diabetes, and cardiovascular diseases. Circ. Res. 2020, 126,1477–1500.

- Abraham, T.M.; Pedley, A.; Massaro, J.M.; Hoffmann, U.; Fox, C.S. Association between visceral and subcutaneous adipose depots and incident cardiovascular disease risk factors. Circulation 2015, 132, 1639–1647.

- Fantuzzi, G.; Mazzone, T. Adipose tissue and atherosclerosis: exploring the connection. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007, 27, 996–1003.

- Ouwens, D.M.; Sell, H.; Greulich, S.; Eckel, J. The role of epicardial and perivascular adipose tissue in the pathophysiology of cardiovascular disease.J. Cell. Mol. Med. 2010, 14, 2223–2234.

- Iozzo, P. Myocardial, perivascular, and epicardial fat. Diabetes Care 2011, 34, S371–379.

- Ng, A.C.; Delgado, V.; Djaberi, R.; Schuijf, J.D.; Boogers, M.J.; Auger, D.; Bertini, M.; de Roos, A.; van der Meer, R.W.; Lamb, H.J.; et al. Multimodality imaging in diabetic heart disease. Curr. Probl. Cardiol. 2011, 36, 9–47.

- Patel, V.B.; Shah, S.; Verma, S.; Oudit, G.Y. Epicardial adipose tissue as a metabolic transducer: Role in heart failure and coronary artery disease. Heart Fail. Rev. 2017, 22, 889–902.

- McGavock, J.M.; Lingvay, I.; Zib, I.; Tillery, T.; Salas, N.; Unger, R.; Levine, B.D.; Raskin, P.; Victor, R.G.; Szczepaniak, L.S. Cardiac steatosis in diabetes mellitus: A 1H-Magnetic resonance spectroscopy study. Circulation 2007, 116, 1170–1175.

- De Munck, T.J.I.; Soeters, P.B.; Koek, G.H. The role of ectopic adipose tissue: benefit or deleterious overflow? Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 75, 38–48.

- Song, Y.; Song, F.; Wu, C.; Hong, Y.X.; Li, G. The roles of epicardial adipose tissue in heart failure. Heart Fail. Rev. 2020, doi:10.1007/s10741-020-09997-x. Online ahead of print.

- Verhagen, S.N.; Visseren, F.L. Perivascular adipose tissue as a cause of atherosclerosis. Atherosclerosis 2011, 214, 3–10.

- Neeland, I.J.; Yokoo, T.; Leinhard, O.D.; Lavie, C.J. Twenty-First century advances in multimodality imaging of obesity for care of the cardiovascular patient. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2020, 14, 482–494, doi:10.1016/j.jcmg.2020.02.031.

- Iacobellis, G. Epicardial and pericardial fat: Close, but very different. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2009, 17, 625.

- de Wit-Verheggen, V.H.W.; Altintas, S.; Spee, R.J.M.; Mihl, C.; van Kuijk, S.M.J.; Wildberger, J.E.; Schrauwen-Hinderling, V.B.; Kietselaer, B.L.J.H.; van de Weijer, T. Pericardial fat and its influence on cardiac diastolic function. Cardiovasc. Diabetol. 2020, 19, 129.

- Xu, L.; Xu, Y.; Coulden, R.; Sonnex, E.; Hrybouski, S.; Paterson, I.; Butler, C. Comparison of epicardial adipose tissue radi-odensity threshold between contrast and non-contrast enhanced computed tomography scans: A cohort study of derivation and validation. Atherosclerosis 2018, 275, 74–79.

- Hajer, G.R.; van Haeften, T.W.; Visseren, F.L. Adipose tissue dysfunction in obesity, diabetes, and vascular diseases. Eur. Heart J. 2008, 29, 2959–2971.

- Antoniades, C.; Kotanidis, C.P.; Berman, D.S. State-of-the-Art review article. Atherosclerosis affecting fat: What can we learn by imaging perivascular adipose tissue? J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 2019, 13, 288–296.

- Salazar, J.; Luzardo, E.; Mejías, J.C.; Rojas, J.; Ferreira, A.; Rivas-Ríos, J.R.; Bermúdez, V. Epicardial fat: Physiological, patho-logical, and therapeutic implications. Cardiol. Res. Pract. 2016, 1291537, doi:10.1155/2016/1291537.

- Dai, X.; Deng, J.; Yu, M.; Lu, Z.; Shen, C.; Zhang, J. Perivascular fat attenuation index and high-risk plaque features evaluated by coronary CT angiography: Relationship with serum inflammatory marker level. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2020, 36, 723–730.

- Rosito, G.A.; Massaro, L.M.; Hoffmann, U.; Ruberg, F.L.; Mahabadi, A.A.; Vasan, R.S.; O’Donnell, C.J.; Fox, C.S. Pericardial fat, visceral abdominal fat, cardiovascular disease risk factors, and vascular calcification in a community-based sample: The framingham heart study. Circulation 2008, 117, 605–613.

- Ding, J.; Hsu, F.C.; Harris, T.B.; Liu, Y.; Kritchevsky, S.B.; Szklo, M.; Ouyang, P.; Espeland, M.A.; Lohman, K.K.; Criqui, M.H.; et al. The association of pericardial fat with incident coronary heart disease: The multi-ethnic study of atherosclerosis (ME-SA). Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 499–504.

- Shah, R.V.; Anderson, A.; Ding, J.; Budoff, M.; Rider, O.; Petersen, S.E.; Jensen, M.K.; Koch, M.; Allison, M.; Kawel-Boehm, N.; et al. Pericardial, but not hepatic, fat by CT is associated with CV outcomes and structure: The multi-ethnic study of athero-sclerosis. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging 2017, 10, 1016–1027.

- Schlett, C.L.; Ferencik, M.; Kriegel, M.F.; Bamberg, F.; Ghoshhajra, B.B.; Joshi, S.B.; Nagurney, J.T.; Fox, C.S.; Truong, Q.A.; Hoffmann, U. Association of pericardial fat and coronary high-risk lesions as determined by cardiac CT. Atherosclerosis 2012, 222, 129–134.

- Hatem, S.N.; Redheuil, A.; Gandjbakhch, E. Cardiac adipose tissue and atrial fibrillation: The perils of adiposity. Cardiovasc. Res. 2016, 109, 502–509.

- Petrini, M.; Alì, M.; Cannaò, P.M.; Zambelli, D.; Cozzi, A.; Codari, M.; Malavazos, A.E.; Secchi, F.; Sardanelli, F. Epicardial adipose tissue volume in patients with coronary artery disease or non-ischaemic dilated cardiomyopathy: Evaluation with cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Clin. Radiol. 2019, 74, 81.e1–81.e7.

- Fraum, T.J.; Ludwig, D.R.; Bashir, M.R.; Fowler, K.J. Gadolinium-Based contrast agents: A comprehensive risk assessment. J. Magn. Reson. Imaging. 2017, 46, 338–353.

- Ng, A.C.T.; Strudwick, M.; van der Geest, R.J.; Ng, A.C.C.; Gillinder, L.; Goo, S.Y.; Cowin, G.; Delgado, V.; Wang, W.Y.S.; Bax, J.J. Impact of epicardial adipose tissue, left ventricular myocardial fat content, and interstitial fibrosis on myocardial contractile function. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2018, 11, e007372.

- van de Weijer, T.; Paiman, E.H.M.; Lamb, H.J. Cardiac metabolic imaging: Current imaging modalities and future perspec-tives. J. Appl. Physiol. (1985). 2018, 124, 168–181.

- Kropidlowski, C.; Meier-Schroers, M.; Kuetting, D.; Sprinkart, A.; Schild, H.; Thomas, D.; Homsi, R. CMR based measure-ment of aortic stiffness, epicardial fat, left ventricular myocardial strain and fibrosis in hypertensive patients. Int. J. Cardiol. Heart Vasc. 2020, 27, 100477.

- Rijzewijk, L.J.; van der Meer, R.W.; Smit, J.W.; Diamant, M.; Bax, J.J.; Hammer, S.; Romijn, J.A.; de Roos, A.; Lamb, H.J. Myo-cardial steatosis is an independent predictor of diastolic dysfunction in type 2 diabetes mellitus. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2008, 52, 1793–1799.

- Cannavale, G.; Francone, M.; Galea, N.; Vullo, F.; Molisso, A.; Carbone, I.; Catalano, C. Fatty images of the heart: Spectrum of normal and pathological findings by computed tomography and cardiac magnetic resonance imaging. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 2018, 5610347.

- Hassan, M.; Said, K.; Rizk, H.; ElMogy, F.; Donya, M.; Houseni, M.; Yacoub, M. Segmental peri-coronary epicardial adipose tissue volume and coronary plaque characteristics. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2016, 17, 1169–1177.

- Nelson, M.R.; Mookadam, F.; Thota, V.; Emani, U.; Al Harthi, M.; Lester, S.J.; Cha, S.; Stepanek, J.; Hurst, R.T.; et al. Epicardi-al fat: An additional measurement for subclinical atherosclerosis and cardiovascular risk stratification? J. Am. Soc. Echocar-diogr. 2011, 24, 339–345.

- Bertaso, A.G.; Bertol, D.; Duncan, B.B.; Foppa, M. Epicardial Fat: Definition, measurements and systematic review of main outcomes. Arq. Bras. Cardiol. 2013, 101, e18–e28.

- Ahn, S.G.; Lim, H.-S.; Joe, D.Y.; Kang, S.J.; Choi, B.J.; Choi, S.Y.; Yoon, M.H.; Hwang, G.S.; Tahk, S.J.; Shinet, J.H. Relationship of epicardial adipose tissue by echocardiography to coronary artery disease. Heart 2008, 94, e7.

- Okyay, K.; Balcioglu, A.; Tavil, Y.; Tacoy, G.; Turkoglu, S.; Abaci, A. A relationship between echocardiographic subepicardi-al adipose tissue and metabolic syndrome. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2008, 24, 577–583.

- Mahabadi, A.A.; Berg, M.H.; Lehmann, N.; Kälsch, H.; Bauer, M.; Kara, K.; Dragano, N.; Moebus, S.; Jöckel, K.H.; Erbel, R.; et al. Association of epicardial fat with cardiovascular risk factors and incident myocardial infarction in the general popula-tion: The Heinz Nixdorf recall study. JACC 2013, 61, 1388–1395.

- Kirchhof, P.; Benussi, S.; Kotecha, D.; Ahlsson, A.; Atar, D.; Casadei, B.; Castella, M.; Diener, H.C.; Heidbuchel, H.; Hendriks, J.; et al. 2016 ESC guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with EACTS. Eur. Heart. J. 2016, 37,2893–2962.

- Allessie, M.A.; Boyden, P.A.; Camm, A.J.; Kléber, A.G.; Lab, M.J.; Legato, M.J.; Rosen, M.R.; Schwartz, P.J.; Spooner, P.M.; Van Wagoner, D.R.; et al. Pathophysiology and prevention of atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2001, 103, 769–777.

- Markides, V.; Schilling, R.J. Atrial fibrillation: Classification, pathophysiology, mechanisms and drug treatment. Heart 2003, 89, 939–943.

- Haïssaguerre, M.; Jaïs, P.; Shah, D.C.; Takahashi, A.; Hocini, M.; Quiniou, G.; Garrigue, S.; Le Mouroux, A.; Le Métayer, P.; Clémenty, J. Spontaneous initiation of atrial fibrillation by ectopic beats originating in the pulmonary veins. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998, 339, 659–666.

- Narayan, S.M.; Patel, J.; Mulpuru, S.; Krummen, D.E. Focal impulse and rotor modulation ablation of sustaining rotors ab-ruptly terminates persistent atrial fibrillation to sinus rhythm with elimination on follow-up: A video case study. Heart Rhythm 2012, 9, 1436–1439.

- Gianni, C.; Mohanty, S.; Di Biase, L.; Metz, T.; Trivedi, C.; Gökoğlan, Y.; Güneş, M.F.; Bai, R.; Al-Ahmad, A.; Burkhardt, J.D.; et al. Acute and early outcomes of focal impulse and rotor modulation (FIRM)-Guided rotors-only ablation in patients with nonparoxysmal atrial fibrillation. Heart Rhythm 2016, 13, 830–835.

- Stavrakis, S.; Kulkarni, K.; Singh, J.P.; Katritsis, D.G.; Armoundas, A.A. Autonomic modulation of cardiac arrhythmias: Methods to assess treatment and outcomes. JACC Clin. Electrophysiol. 2020, 6,467–483.

- Shen, M.J.; Choi, E.K.; Tan, A.Y.; Lin, S.F.; Fishbein, M.C.; Chen, L.S.; Chen, P.S. Neural mechanisms of atrial arrhythmias. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2011, 9, 30–39.

- Nattel, S.; Burstein, B.; Dobrev, D. Atrial remodeling and atrial fibrillation: Mechanisms and implications. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2008, 1, 62.

- Allessie, M.A.; de Groot, N.M.; Houben, R.P.; Schotten, U.; Boersma, E.; Smeets, J.L.; Crijns, H.J. Electropathological sub-strate of long-standing persistent atrial fibrillation in patients with structural heart disease: Longitudinal dissociation. Circ. Arrhythm. Electrophysiol. 2010, 3, 606–615.

- Brundel, B.J.; Van Gelder, I.C.; Henning, R.H.; Tieleman, R.G.; Tuinenburg, A.E.; Wietses, M.; Grandjean, J.G.; Van Gilst, W.H.; Crijns, H.J. Ion channel remodeling is related to intraoperative atrial effective refractory periods in patients with paroxysmal and persistent atrial fibrillation. Circulation 2001, 103, 684–690.

- Schotten, U.; Verheule, S.; Kirchhof, P.; Goette, A. Pathophysiological mechanisms of atrial fibrillation: A translational ap-praisal. Physiol. Rev. 2011, 91, 265–325.

- van der Velden, H.M.; Ausma, J.; Rook, M.B.; Hellemons, A.J.; van Veen, T.A.; Allessie, M.A.; Jongsma, H.J. Gap junctional remodeling in relation to stabilization of atrial fibrillation in the goat. Cardiovasc. Res. 2000, 46, 476–486.

- Dzeshka, M.S.; Lip, G.Y.; Snezhitskiy, V.; Shantsila, E. Cardiac fibrosis in patients with atrial fibrillation: Mechanisms and clinical implications. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2015, 66, 943.

- Nguyen, B.L.; Fishbein, M.C.; Chen, L.S.; Chen, P.S.; Masroor, S. Histopathological substrate for chronic atrial fibrillation in humans. Heart Rhythm 2009, 6, 454–460.

- Venteclef, N.; Guglielmi, V.; Balse, E.; Gaborit, B.; Cotillard, A.; Atassi, F.; Amour, J.; Leprince, P.; Dutour, A.; Clement, K.; et al. Human epicardial adipose tissue induces fibrosis of the atrial myocardium through the secretion of adipo-fibrokines. Eur. Heart J. 2013, 36, 795–805a.

- Hu, Y.F.; Chen, Y.J.; Lin, Y.J.; Chen, S.A. Inflammation and the pathogenesis of atrial fibrillation. Nat. Rev. Cardiol. 2015, 12, 230–243.

- Korantzopoulos, P.; Letsas, K.P.; Tse, G.; Fragakis, N.; Goudis, C.A.; Liu, T. Inflammation and atrial fibrillation: A compre-hensive review. J. Arrhythm. 2018, 34,394–401.

- Gutierrez, A.; Van Wagoner, D.R. Oxidant and inflammatory mechanisms and targeted therapy in atrial fibrillation: An update. J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacol. 2015, 66, 523.

- Harada, M.; Van Wagoner, D.R.; Nattel, S. Role of inflammation in atrial fibrillation pathophysiology and management. Circ. J. 2015, 79, 495–502.