| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Thaschawee Arkachaisri | + 2378 word(s) | 2378 | 2021-02-22 04:19:50 |

Video Upload Options

The transition from pediatric to adult health care is a challenging yet important process in rheumatology as most childhood-onset rheumatic diseases persist into adulthood. Numerous reports on unmet needs as well as evidence of negative impact from poor transition have led to increased efforts to improve transition care, including international guidelines and recommendations. In line with these recommendations, transition programs along with transition readiness assessment tools have been established. This entry focuses on how transition care in rheumatology has developed in recent years and highlights the gaps in current practices.

1. Introduction

With progress in medical care, the prognosis of chronic diseases of childhood onset has improved over the years[1]. As more children survive to adulthood, there is also a need to transit them to adult healthcare services. However, the transition from pediatric care to adult care is often a challenging time for adolescents and young adults (AYA) with chronic medical conditions and their healthcare providers[2]. Transition of care is not simply the physical transfer of patients from pediatric to adult-based medical care. Transitional care is defined by the Society for Adolescent Medicine as “the purposeful, planned movement of adolescents and young adults with chronic physical and medical conditions from child-centered to adult-oriented healthcare systems”[3], which includes an entire process of preparing for the transfer, assessing readiness and ensuring its completion.

A study done to explore the attitudes of 138 physicians and allied health professionals attending the Pediatric Rheumatology European Society (PRES) Congress towards transition showed that 87% were supportive of AYA with active rheumatic diseases receiving follow-up care from adult rheumatologists rather than remaining under pediatric care[4]. However, many expressed dissatisfactions with the state of transition processes for childhood-onset rheumatic diseases. With that, the importance of transition is increasingly acknowledged and significant progress has been made in the understanding of transition care in rheumatology over the last few decades, including development of more structured transition care programs. as well as international guidelines and recommendations.

2. Recognizing the Need for Transition in Rheumatology

Transition care is important in rheumatology, since most childhood-onset rheumatic diseases persist into adulthood. More than half of patients with Juvenile Idiopathic Arthritis (JIA) experienced active disease into adulthood and required ongoing management of immunosuppressants[5][6]. Childhood-onset Systemic Lupus Erythematosus (SLE) is a lifelong disorder with higher morbidity and mortality compared to adult-onset lupus[7]. Without a planned transition care, there is a risk of worsening disease activity in AYA with rheumatic diseases[8]. In a retrospective, single-center study of 31 patients with chronic rheumatic diseases (52% SLE, 16% mixed connective tissue disease 16% JIA, 13% antiphospholipid antibody syndrome and 3% vasculitis), one-third of patients were hospitalized for disease flare in the year before transfer and another one-third experienced an increase in disease activity in the post transfer year[9]. Lack of proper transition plan will therefore result in greater disease damage, poorer quality of life and greater healthcare cost incurred as these AYA progress into adulthood.

The care of AYA with rheumatic diseases has also changed dramatically over the last few decades with increasing use of biological agents and promise of new targeted therapies[10]. Recognizing the need for transition, various recommendations have been published to urge systemic improvement in transition care. The 2014 Institute of Medicine report, “Investing in Health and Well Being of Young Adults,” highlighted the transition from pediatric to adult health care as an important component of improving the health of young adults, particularly those who have chronic disease[11]. A consensus statement issued by American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) and the American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal Medicine (ACP-ASIM) in 2002 set the goals for all physicians taking care of AYA with special healthcare needs to be equipped with the skills to facilitate the transition process[12]. Despite increasing awareness of the need for transition care, AYA still report unmet needs in this area[13]. This is in part due to a lack of general consensus on the best practices in transition care.

3. Development of Rheumatology Transition Programs

Transition care in pediatric rheumatology can be variable and is often dependent on many factors related to the local healthcare system, culture and healthcare funding. There are relatively few well-described models for transition of pediatric rheumatology patients into adult rheumatology care. Sawyer et al. described three general models for transition care for adolescents with chronic illness: (1) disease-focused transition from pediatric care to an adult subspecialist, (2) primary care–coordinated care spanning adolescent to adult care and (3) generic adolescent health services, with care coordinated by adolescent care providers[14]. A primary care–based model is not usually feasible because of the complexity of rheumatic diseases and well-developed adolescent health services are not available in many centers. Therefore, the most practical model for transition care for AYA with rheumatic diseases is a disease-focused transition from pediatric to adult rheumatology services.

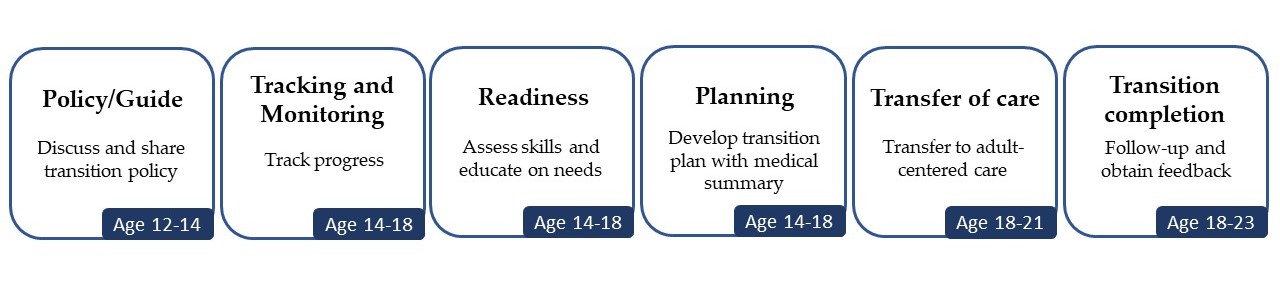

Based on the available models of transition care, recommendations have been published to align transition programs in their broad categories of processes to improve overall transition care. In 2011, the AAP, AAFP and American College of Physicians (ACP) jointly outline their suggested approach including the need to assess readiness, patient education, preparation of a medical summary and communication between the pediatric and adult healthcare providers[12]. Got Transition, a federally funded national resource center on healthcare transition in the United States, developed a structured approach called the Six Core Elements of Health Care Transition (Figure 1), which define the basic components of a structured transition process and include customizable tools for each core element[15].

Children with rheumatic disease have a wide range of transition needs based on multiple factors such as disease activity, readiness, cognitive and executive functioning proficiency, home support structures and socioeconomic factors[16]. To assist with implementation of the Six Core Elements, the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) joined the ACP Pediatric to Adult Care Transitions Initiative and formed the ACR Transition Work Group. They developed a subspecialty-specific toolkit tailored to pediatric and adult rheumatologists to assist them in transitioning their patients[17]. In the UK, McDonagh et al. proposed a transition program based on needs assessments using focus groups, a national survey of health professionals, Delphi analysis and retrospective case audits[18]. Tucker and Cabral proposed a transition model involving joint clinic between pediatric and adult rheumatologists, with assistance of a multidisciplinary team[19]. This clinic encouraged patient independence while discouraging over reliance on parents in in making medical management decisions. Rettig and Athreya described a rheumatology specific transition model that uses a multidisciplinary team and a nurse coordinator[20]. The program comprises pre-transitional assessments and interventions that address common adolescent issues.

To integrate the existing models of transition of care for AYA with juvenile onset rheumatic diseases, a task force of the Pediatric Rheumatology European Society (PRES)/European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) developed the first international set of recommendations and standards. It includes 12 consensus recommendations of “essential/minimal” and “ideal/optional” components of transitional care established via international Delphi analysis and systemic literature review. The recommendations emphasized the importance of identifying key individuals, the integral role of AYA and their families, written communication, agreed policy, training and clarity of roles within teams[21]. More recently in 2018, a transitional care checklist was developed to facilitate health professionals in providing transition care for AYA and with rheumatic diseases and their families. This checklist achieved strong international consensus and is recommended to be used by physicians taking caring of adolescents aged ≥12 years at times of transition[22].

Figure 1. The Six Core Elements by Got Transition which define the basic components of a structured transition process.

4. Assessing Outcomes from Rheumatology Transition Programs

Although there are multiple international guidelines and recommendations on transition care of AYA with rheumatic diseases, only few established transition programs have been described in literature. A systematic review and critical appraisal of existing transitional care programs in rheumatology identified eight transition programs in six countries[23]. Common key features include a written transition policy, individualized planning and transition coordinator. However, huge variation in structures, staffing and processes among the programs still exists. Nonetheless, the emergence of transition programs provided valuable insights into the common barriers of transition, important factors in determining readiness and practices that improve success of transition.

In the implementation of transition programs, various transition readiness measures and checklists have also been developed. Examples include the Transition Readiness Assessment Questionnaire (TRAQ), TR(x)ANSITION Scale and AM I ON TRAC (Taking Responsibility for Adolescent/Adult Care)[24][25][26]. Apart from the Readiness for Adult Care in Rheumatology (RACER) questionnaire, most of these transition readiness measures are not specific to rheumatology[27]. Furthermore, high scores on many of these transition measures do not correlate with successful transition[28], indicating that these transition tools may not have holistically addressed the biopsychosocial aspects of transition but instead focus only on disease and health-related factors. The most robustly validated transition readiness tool to date as evaluated by Zhang et al. is the non-condition specific tool, TRAQ[29]. As there are many transition issues unique to rheumatology including self-administration of subcutaneous medication, body image and psychosocial impact from chronic steroid use as well as effect of Disease Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs (DMARDs) on child bearing, this calls for greater research and development of more robust transition tools that are specific to rheumatology.

In the systematic review of transition of care programs performed by working group, an important shortcoming in rheumatology transition programs was also evident—the lack of standardized measures of outcomes and effectiveness. This is similar to other studies of transition in other chronic diseases, where the need for validated measures of transfer satisfaction is highlighted[30]. There have been several proposed quantifiable outcomes to measure successful transition. A consensus-based proposal regarding outcome indicators for successful healthcare transition was recently made albeit not specific to rheumatology[31]. Developing standardized measures of outcomes and effectiveness of transition programs will be paramount in comparing transition programs and defining best models of transition in rheumatology.

5. Transition Programs - The Asian Perspective

Although the critical need for transition care for AYA with rheumatic diseases is a global issue, most guidelines and recommendations are published in the West. To date, there are no publications describing rheumatology transition programs in Asia. Structured transition care is still underdeveloped in many Asian countries. A survey done in Hong Kong revealed that less than 10% of patients with chronic illnesses had ever received transition information from their pediatricians during routine visit, indicating that physicians were not well equipped to facilitate patients and their families to go through the transition process[32].

The lack of awareness in Asia despite increased international efforts to promote transition care is concerning but cultural differences may also account for why transition care is underdeveloped in many Asian countries. Given that transition care is often influenced by local culture and healthcare systems, there are many unique aspects of transition care in Asian context which are important but not necessarily highlighted in guidelines and recommendations from Western literature. In a study published in South Korea looking at healthcare transition readiness in emerging adults with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (T1DM), high scores were obtained in self-perceived competency regarding tasks related to direct glucose control, such as insulin administration and glucose monitoring, when compared to dietary or exercise control[33]. This indicates that while AYA are equipped with skills related to their disease, they may not have the opportunities to establish important aspects of their own lifestyle including diet and exercise, as these aspects are typically controlled by Asian parents. Higher transition readiness scores on disease knowledge and medication management were also reported compared to communication with doctors and engagement during appointments, thus issues surrounding communication with healthcare providers and self-management of lifestyle may be related to cultural and social upbringing, requiring distinct intervention not apparent in current guidelines on transition care planning.

In China, parents were also less likely to foster the AYA’s independence or facilitate his/her self-management because they perceived AYA with chronic disease as more vulnerable. Therefore, they assumed more family responsibilities in caring for AYA with chronic diseases than it is in Western families[34]. In Singapore, 37% of married couples and 97% of singles aged 15 to 34 lived with their parents and were more reliant on parental influence when making decisions[35]. In the development of transition programs in Asian centers, an even greater emphasis should therefore be placed in fostering AYA independence in managing their different aspects of their life and not just disease management.

Parenting styles and family involvement in Asian families are also different from Western families[36]. While it is important to foster AYA independence, family members should not be sidelined in the transition process. Most guidelines focus on improving healthcare system processes and provision of support and knowledge only to AYA. Caregivers’ lack of confidence in AYA’s abilities to manage their conditions and over emphasis on possible negative outcomes can lead to unsuccessful transitions and impede AYA’s self-management of chronic diseases[37]. It is therefore important for transition care guidelines in Asian institutions to provide family management support that focus on augmenting parents’ perception of their children and the chronic diseases. They should be convinced to promote independence and autonomy of their children during the transition process.

6. Conclusion

Effective transition care for AYA is important to rheumatology care provision, especially when active disease and morbidity are still observed in adulthood in many of the rheumatic diseases. Table 1 summarizes the key elements of a transition program. Successful transition has major implications to both AYA and their families. In recent years, there has been increasing interest surrounding transition and its recognition has become more prominent in rheumatology, leading to the publication of specific guidelines. Despite all these efforts, much remain to be done. Future research will need to focus on implementing standardized outcomes measures in evaluation of transition programs and regional guidelines should also be developed with consideration of different cultural context in the Asian rheumatology population.

| Key Elements of a Transition Program |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Table 1. Key elements of a transition program

References

- Niraj Sharma; Kitty O’Hare; Richard C. Antonelli; Gregory S. Sawicki; Transition Care: Future Directions in Education, Health Policy, and Outcomes Research. Academic Pediatrics 2014, 14, 120-127, 10.1016/j.acap.2013.11.007.

- R Crowley; I Wolfe; K Lock; M McKee; Improving the transition between paediatric and adult healthcare: a systematic review. Archives of Disease in Childhood 2011, 96, 548-553, 10.1136/adc.2010.202473.

- Robert Wm. Blum; Dale Garell; Christopher H. Hodgman; Timothy W. Jorissen; Nancy A. Okinow; Donald P. Orr; Gail B. Slap; Transition from child-centered to adult health-care systems for adolescents with chronic conditions. Journal of Adolescent Health 1993, 14, 570-576, 10.1016/1054-139x(93)90143-d.

- Deborah Hilderson; Philip Moons; Rene Westhovens; Carine Wouters; Attitudes of rheumatology practitioners toward transition and transfer from pediatric to adult healthcare. Rheumatology International 2011, 32, 3887-3896, 10.1007/s00296-011-2273-4.

- Anne M Selvaag; Hanne A Aulie; Vibke Lilleby; Berit Flatø; Disease progression into adulthood and predictors of long-term active disease in juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2014, 75, 190-195, 10.1136/annrheumdis-2014-206034.

- Kirsten Minden; Martina Niewerth; Joachim Listing; Thomas Biedermann; Matthias Bollow; Monika Schöntube; Angela Zink; Long-term outcome in patients with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Arthritis & Rheumatism 2002, 46, 2392-2401, 10.1002/art.10444.

- Rina Mina; Hermine I Brunner; Update on differences between childhood-onset and adult-onset systemic lupus erythematosus. Arthritis Research & Therapy 2013, 15, 218-218, 10.1186/ar4256.

- Rebecca E. Sadun; Richard J. Chung; Gary R. Maslow; Transition to Adult Health Care and the Need for a Pregnant Pause. PEDIATRICS 2019, 143, e20190541, 10.1542/peds.2019-0541.

- Aimee O Hersh; Shirley Pang; Megan L Curran; Diana S Milojevic; Emily Von Scheven; The challenges of transferring chronic illness patients to adult care: reflections from pediatric and adult rheumatology at a US academic center. Pediatric Rheumatology 2009, 7, 13-13, 10.1186/1546-0096-7-13.

- S. A. Kerrigan; I. B. McInnes; JAK Inhibitors in Rheumatology: Implications for Paediatric Syndromes?. Current Rheumatology Reports 2018, 20, 1-9, 10.1007/s11926-018-0792-7.

- Patience H. White; Margaret McManus; Investing in the Health and Well-Being of Young Adults.. Journal of Adolescent Health 2015, 57, 126, 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2015.04.005.

- W. Carl Cooley; Paul J. Sagerman; Supporting the Health Care Transition From Adolescence to Adulthood in the Medical Home. PEDIATRICS 2011, 128, 182-200, 10.1542/peds.2011-0969.

- Ivy Jiang; Gabor Major; Davinder Singh-Grewal; Claris Teng; Ayano Kelly; Fiona Niddrie; Jeffrey Chaitow; Sean O’Neill; Geraldine Hassett; Arvin Damodaran; et al.Sarah BernaysKarine ManeraAllison TongDavid J Tunnicliffe Patient and parent perspectives on transition from paediatric to adult healthcare in rheumatic diseases: an interview study. BMJ Open 2021, 11, e039670, 10.1136/bmjopen-2020-039670.

- S M Sawyer; S Blair; G Bowes; Chronic illness in adolescents: Transfer or transition to adult services?. Journal of Paediatrics and Child Health 1997, 33, 88-90, 10.1111/j.1440-1754.1997.tb01005.x.

- The Six Core Elements of Health Care Transition 2.0 . 34. Got Transition Center for Health Care Transition Improvement. Retrieved 2021-3-2

- Sara Sabbagh; Tova Ronis; Patience H White; Pediatric rheumatology: addressing the transition to adult-orientated health care. Open Access Rheumatology: Research and Reviews 2018, ume 10, 83-95, 10.2147/oarrr.s138370.

- Pediatric to Adult Rheumatology Care Transition . Pediatric to Adult Rheumatology Care Transition. Retrieved 2021-3-2

- J. E. McDonagh; T. R. Southwood; K. L. Shaw; On Behalf Of The British Society Of Paediatric And Adolescent Rheumatology; The impact of a coordinated transitional care programme on adolescents with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. Rheumatology 2007, 46, 161-168, 10.1093/rheumatology/kel198.

- Lori B. Tucker; David A. Cabral; Transition of the Adolescent Patient with Rheumatic Disease: Issues to Consider. Rheumatic Disease Clinics of North America 2007, 33, 661-672, 10.1016/j.rdc.2007.07.005.

- Patty Rettig; Balu H. Athreya; Adolescents with chronic disease. Transition to adult health care. Arthritis Care & Research 1991, 4, 174-180, 10.1002/art.1790040407.

- Helen E Foster; Kirsten Minden; Daniel Clemente; Leticia Leon; Janet E McDonagh; Sylvia Kamphuis; Karin Berggren; Philomine Van Pelt; Carine Wouters; Jennifer Waite-Jones; et al.Rachel TattersallRuth WyllieSimon R. StonesAlberto MartiniTamas ConstantinSusanne SchalmBerna FidanciBurak ErerErkan DermikayaSeza OzenLoreto Carmona EULAR/PReS standards and recommendations for the transitional care of young people with juvenile-onset rheumatic diseases. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2016, 76, 639-646, 10.1136/annrheumdis-2016-210112.

- Christina Akre; Joan-Carles Suris; Alexandre Belot; Marie Couret; Thanh-Thao Dang; Agnès Duquesne; Béatrice Fonjallaz; Sophie Georgin-Lavialle; Jean-Paul Larbre; Johannes Mattar; et al.Anne MeynardSusanne SchalmMichaël Hofer Building a transitional care checklist in rheumatology: A Delphi-like survey. Joint Bone Spine 2018, 85, 435-440, 10.1016/j.jbspin.2017.09.003.

- Daniel Clemente; Leticia Leon; Helen Foster; Kirsten Minden; Loreto Carmona; Systematic review and critical appraisal of transitional care programmes in rheumatology. Seminars in Arthritis and Rheumatism 2016, 46, 372-379, 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2016.06.003.

- Melissa Moynihan; Elizabeth Saewyc; Sandra Whitehouse; Mary Paone; Gladys McPherson; Assessing readiness for transition from paediatric to adult health care: Revision and psychometric evaluation of the Am I ON TRAC for Adult Care questionnaire. Journal of Advanced Nursing 2015, 71, 1324-1335, 10.1111/jan.12617.

- Maria E Ferris; Donna H Harward; Kristi Bickford; J. Bradley Layton; M. Ted Ferris; Susan L Hogan; Debbie S Gipson; Lynn P McCoy; Stephen R Hooper; A Clinical Tool to Measure the Components of Health-Care Transition from Pediatric Care to Adult Care: The UNC TR x ANSITION Scale. Renal Failure 2012, 34, 744-753, 10.3109/0886022x.2012.678171.

- A. F. Klassen; C. Grant; R. Barr; H. Brill; O. Kraus De Camargo; G. M. Ronen; M. C. Samaan; T. Mondal; S. J. Cano; A. Schlatman; et al.E. TsangarisU. AthaleN. WickertJ. W. Gorter Development and validation of a generic scale for use in transition programmes to measure self‐management skills in adolescents with chronic health conditions: the TRANSITION ‐ Q. Child: Care, Health and Development 2014, 41, 547-558, 10.1111/cch.12207.

- J. Stinson; L. Spiegel; K. Watanabe Duffy; L. Tucker; E. Stringer; B. Hazel; J. Hochman; N. Gill; K. Spadafora; M. Kaufman; et al. THU0320 Development and testing of the readiness for adult care in rheumatology (RACER) questionnaire for adolescents with rheumatic conditions. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 2013, 71, 264.1-264, 10.1136/annrheumdis-2012-eular.2285.

- Paul T. Jensen; Gabrielle V. Paul; Stephanie LaCount; Juan Peng; Charles H. Spencer; Gloria C. Higgins; Brendan Boyle; Manmohan Kamboj; Christopher Smallwood; Stacy P. Ardoin; et al. Assessment of transition readiness in adolescents and young adults with chronic health conditions. Pediatric Rheumatology 2017, 15, 1-7, 10.1186/s12969-017-0197-6.

- Lorena F Zhang; Jane Sw Ho; Sean E Kennedy; A systematic review of the psychometric properties of transition readiness assessment tools in adolescents with chronic disease. BMC Pediatrics 2014, 14, 4-4, 10.1186/1471-2431-14-4.

- Jennifer Stinson; Sara Ahola Kohut; Lynn Spiegel; Meghan White; Navreet Gill; Gina Colbourne; Samantha Sigurdson; Karen Watanabe Duffy; Lori Tucker; Elizabeth Stringer; et al.Beth HazelJacqueline HochmanJohn ReissMiriam Kaufman A systematic review of transition readiness and transfer satisfaction measures for adolescents with chronic illness. International Journal of Adolescent Medicine and Health 2014, 26, 159-174, 10.1515/ijamh-2013-0512.

- Cynthia D Fair; Jessica Cuttance; Niraj Sharma; Gary R Maslow; Lori Wiener; Cecily Betz; Jerlym S Porter; Suzanne McLaughlin; Jordan Gilleland-Marchak; Amy Renwick; et al.Diana NaranjoSophia JanKarina JavalkarMaria E Ferrisfor the International and Interdisciplinary Health Care Transition Research Consortium International and Interdisciplinary Identification of Health Care Transition Outcomes. JAMA Pediatrics 2016, 170, 205-211, 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.3168.

- Lilian H.L. Wong; Frank W.K. Chan; Fiona Y.Y. Wong; Eliza L.Y. Wong; Kwai Fun Huen; Eng-Kiong Yeoh; Tai-Fai Fok; Transition Care for Adolescents and Families With Chronic Illnesses. Journal of Adolescent Health 2010, 47, 540-546, 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2010.04.002.

- Gayeong Kim; Eun Kyoung Choi; Hee Soon Kim; Heejung Kim; Ho-Seong Kim; Healthcare Transition Readiness, Family Support, and Self-management Competency in Korean Emerging Adults with Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus. Journal of Pediatric Nursing 2019, 48, e1-e7, 10.1016/j.pedn.2019.03.012.

- Nan Sheng; Jiali Ma; Wenwen Ding; Ying Zhang; Family management affecting transition readiness and quality of life of Chinese children and young people with chronic diseases. Journal of Child Health Care 2018, 22, 470 - 485, 10.1177/1367493517753712.

- Bernice Tan; David Ong; Pediatric to adult inflammatory bowel disease transition: the Asian experience. Intestinal Research 2020, 18, 11-17, 10.5217/ir.2019.09144.

- Helen Y. Sung; The Influence of Culture on Parenting Practices of East Asian Families and Emotional Intelligence of Older Adolescents. School Psychology International 2010, 31, 199-214, 10.1177/0143034309352268.

- Michele Polfuss; Elizabeth Babler; Loretta L. Bush; Kathleen Sawin; Family Perspectives of Components of a Diabetes Transition Program. Journal of Pediatric Nursing 2015, 30, 748-756, 10.1016/j.pedn.2015.05.010.

- Michele Polfuss; Elizabeth Babler; Loretta L. Bush; Kathleen Sawin; Family Perspectives of Components of a Diabetes Transition Program. Journal of Pediatric Nursing 2015, 30, 748-756, 10.1016/j.pedn.2015.05.010.