| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Juan C. Mejuto | + 4596 word(s) | 4596 | 2021-02-24 06:57:56 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | -2947 word(s) | 1649 | 2021-03-02 02:54:16 | | |

Video Upload Options

Agro-industries should adopt effective strategies to use agrochemicals such as glyphosate herbicides cautiously in order to protect public health. This entails careful testing and risk assessment of available choices, and also educating farmers and users with mitigation strategies in ecosystem protection and sustainable development.

1. Introduction

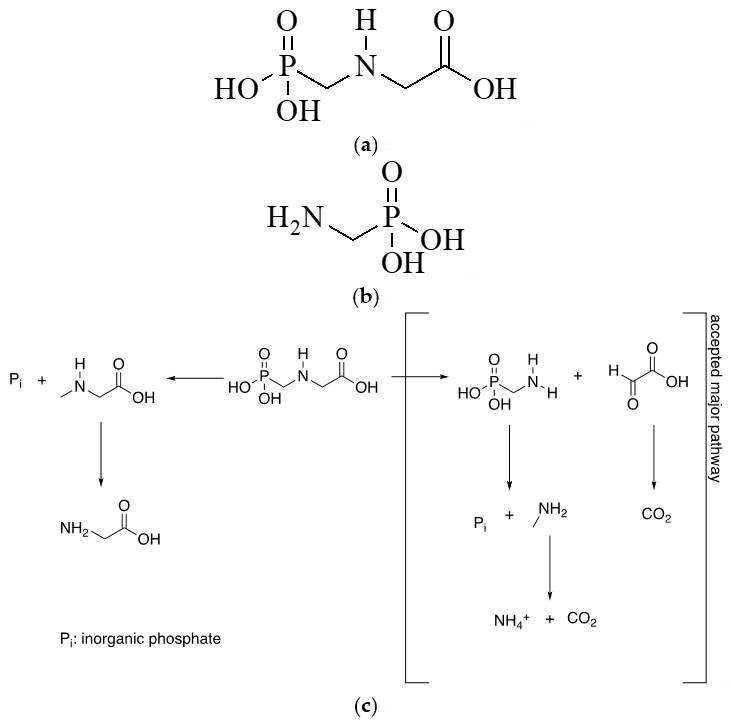

Glyphosate (N-phosphonomethylglycine; Figure 1a) is an aminophosphonate. This compound is typically used as a broad-spectrum herbicide and is absorbed by plant leaves. Glyphosate, discovered in the 1970s, was registered in more than 130 countries [1], and the use of glyphosate-based herbicides increased 100 times since then [2]. Genetically engineered herbicide-tolerant (GEHT) crops have considerably facilitated weed management in cotton, soybean, and maize [3][4][5]. However, they have also caused the emergence of glyphosate-resistant weed phenotypes [3][4][5][6][7][8]. The incorporation of additional herbicides into spraying programs [6][7] has caused herbicide per hectare on crops with GEHT varieties to escalate in this century [5][8][9]. This upward trend is expected to result in heavier environmental loads and increased human exposure to herbicides, including glyphosate and its main metabolite, aminomethylphosphonic acid (AMPA; Figure 1b), and to the adjuvants contained in its formulations. Weed management should face resistance before it happens [10]. It is key to promote changing crops or crop rotations against herbicide resistant (HR) weeds with effective herbicides [11]. Non-herbicidal alternatives (natural products, selective herbicides, mechanical controls, etc.) need to be added to satisfy the reduced efficacy of herbicides [12].

Figure 1c shows the degradation pathway for glyphosate in soil [13]. Although leaching of glyphosate is very unlikely due to its high soil sorption, depending on the type of soil, it can move to ground and surface waters through leaching and runoff [14]. Human exposure to urban sources of glyphosate should be considered too. Although some nonselective (broad spectrum) herbicides for both urban and home use in emerging countries contain glyphosate at low levels—and pose little risk of acute toxic exposure as a result [15]—those used in developing countries contain higher levels of this compound, or are mixed without official control. Dietary exposure in areas lacking residue information can be assessed from data for areas where glyphosate use and residues have been accurately determined [16].

Figure 1. Structural formula of glyphosate (a) and AMPA –(aminomethyl)phosphonic acid– (b), together with degradation pathway for glyphosate in soil (c).

The glyphosate mechanism as herbicidal involves inhibition of 5-enolpyruvylshikimate-3-phosphate synthase (EPSPS), which interferes with phenylalanine, tyrosine, and tryptophan synthesis. Unlike plants and some microorganisms, mammals have no EPSPS, which is in principle an advantage safety-wise [17]. However, glyphosate herbicides are highly controversial in toxicological and environmental terms. This review, therefore, diagnoses on the use of glyphosate and the associated development of glyphosate-resistant weeds. It also deals with the risk assessment on human health of glyphosate formulations through environment and dietary exposures based on the impact of glyphosate and its metabolite AMPA on water and food. All this to setup further conclusions and recommendations on the regulated use of glyphosate and how to mitigate the adverse effects in the below selected sections.

2. Glyphosate-Resistant Weeds

The international database on herbicide resistance [18] contains more than 510 studies. The best resistance mainframe is based on prevention and on detection with regular appraisal of herbicides-treated fields [19]. There are various methods to detect resistance with tests in the field and with bioassays in greenhouses and laboratories [20]; for example, hybridization between A. palmeri and A. spinosus occurred with frequencies in the field studies ranging from <0.01% to 0.4%, and 1.4% in greenhouse crosses [21]. Non-target-site resistance (NTSR) to herbicides in weeds can be conferred as a result of the alteration of one or more physiological processes, including herbicide absorption, translocation, sequestration, and metabolism. The mechanisms of NTSR are generally more complex to decipher than target-site resistance (TSR) and can impart cross-resistance to herbicides with different modes of action. Metabolism-based NTSR has been reported in many agriculturally important weeds, although reduced translocation and sequestration of herbicides has also been found in some weeds [22][23]. Crossed resistance is when the plant developed resistance to an herbicide, which permits to resist herbicides with the same action mode [24]. Multiple resistance is when a plant has one or several mechanisms of resistance to herbicides with distinct action modes. The selection pressure of an herbicide is then capable to select resistant plant biotypes depending on the herbicide treatment type, its formulation, application frequency, and the biological characteristics of the weed and the crop [25][26][27][28]. Examples of glyphosate-resistant weeds and their locations can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Example of glyphosate-resistant weeds and their locations, extended from reference [29].

|

Weed |

Location |

|

Amaranthus palmeri |

United States |

|

Amaranthus tuberculatus |

United States |

|

Ambrosia artemissifolia |

United States |

|

Ambrosia trifida |

United States |

|

Conyza bonariensis |

United States, Brazil, Argentina |

|

Conyza canadensis |

United States |

|

Euphorbia heterophylla |

Brazil |

|

Lolium perenne |

United States, Brazil, Australia |

|

Sorghum halepense |

United States, Argentina |

The problem is compounded by non-target site multiple resistances in grasses, as is the case of Lolium rigidum and Alopecurus myosuroides [12][26]. In addition, the growing expansion of multiple resistance to broadleaf weeds is bound to worsen things in the future. Managing non-target site resistance is difficult owing to the many unpredictable resistance patterns against which rotating herbicide sites of action may be ineffective. Herbicides are the main means for weed control in developed countries, but they should be used more sustainably [30]. This entails not only using improved herbicide mixtures and rotations, but still adopting intensive integrated weed management programs including effective mechanical and cultural strategies [31]. A pressing need therefore exists for economic incentives to the search for new, safer, and more effective herbicides [4].

Developing herbicide-resistance crop traits may grant the use of old herbicides in new ways through tailored mixtures efficiently avoiding multiple resistance [32][33]. Indeed, the use of different genetic engineering techniques as RNA interference (RNAi) [3][32][34][35][36][37][38], chimeric RNA/DNA oligonucleotides [39], and gene-editing techniques (GM), such as CRISPR/Cas9 or CRISPR/Cpf1 [40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48] technology, might be useful for this purpose. The best approach to prevent resistant weeds is to use a combined weed management, and herbicides will likely be partly replaced with new technologies such as, among others, research on crop allelopathy [49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56] and engineering of microbial control agents [57][58][59][60][61]. Progress in these technologies is expected to allow methods for weed control to be used in an integrated manner with the aim of maximizing diversity in weed control and minimizing resistance. Applying evolutionary principles to agricultural settings is essential to properly understand the system-wide effects of herbicide selection intensity [62]. Although the main driver of herbicide resistance is the selection pressure of management, further knowledge of the scientific bases of herbicide resistance at the genetic and cellular levels needs to be developed [63][64][65][66][67]. The causes and dynamics of resistance expansion might be elucidated by assessing the flexibility of certain alleles involved in herbicide resistance [68]. The capability of resistant weeds to prevail, replicate, and selectively infest habitats depends on the degree of vigour of the particular resistant gene [69]. The effects of the environment on resistant plants in cropping conditions could thus reduce the heritability and frequencies of resistance alleles with time [70].

Research in this field should also address the effects of climate change on the expansion of herbicide resistance. According to Renton [71], spatially computational models could be of help in this context by providing powerful indicators on how genetics, plant biology, population structure, environmental conditions, and management strategies connect to shape weed resistance dynamics. The use of scarcely diverse practices drove to a fast increment in multiple-resistance weeds with upgraded abilities for herbicide metabolism worldwide [72]. Elucidating herbicide metabolic pathways could help re-classify and re-rank the risks of herbicide resistance and hence enable the adoption of more effective herbicide rotations, such as those based on both site of action and metabolic pathway. Processes associated with climatic changes, such as elevated temperatures, can strongly affect weed control efficiency. For example, responses of several grass weed populations to herbicides that inhibit acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACCase) were examined under different temperature regimes [73].

Mitigation Strategies

Weed resistance management has three planks: rotate modes of action to reduce selection pressure, incorporate non-chemical practices and control weed seed set, together with asexual reproduction (rhizomes, stolons, etc.). Effective weed control needs to discern weeds biology, prevents with weed seed production, plant into weed-free fields, grow weed-free seed, and inspect lands regularly. There is also a need to adopt numerous herbicide action mechanisms active versus damaging weeds, spread herbicide estimate at selected weed extents, and highlight growing conditions that put an end to weeds by crop competition. Further, it is useful to practice mechanical and biological executive strategies, avoid field-to-field and within-field migration of weed vegetative propagules, regulate weed seed to avoid a reinforcement of the weed seed-stock, and preclude an invasion of weeds into land by controlling ground boundaries. All these diverse approaches to managing herbicide resistance need to be incorporated into weed management [74][75][76][77][78].

This will be beneficial in managing resistance in the long term, together with mathematical simulations proving that mixtures magnify herbicide efficacy, choice array of soil-applied herbicides, and postpone herbicide resistance growth in weeds. It shows than extension efforts rotating herbicide mixtures give vision to guide the progression of weed resistance [69]. Multiple modes of action (MOAs) for weed control are important for managing herbicide resistance and enabling no-till farming practices that help to sequester greenhouse gases, but discovering new herbicide MOAs has been a challenge for the industry [76].

According to the International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development [79] (IAASTD, 2008), agricultural development has focused on increasing farm-level yield, more than on consolidating effects on biodiversity and the liaison of agriculture with climate change. Increased attention needs to be directed to build up soil fertility and to sustain agricultural production, with a focus also on protection of biodiversity. Agro-ecology refers to treating agricultural ecosystems as ecosystems, and can enable a successful transition to more sustainable farming and food systems [80].

Moreover, in recent decades, studies were performed looking for alternatives to glyphosate. There is a rise in efficacy tests using different natural (or even modified) allelo-chemicals obtained from essential oils for pest-control [81][82][83][84][85][86][87][88][89][90][91][92][93][94][95][96], as well as in their use as herbicides [97][98][99][100][101][102][103][104][105][106][107][108][109][110][111][112].

References

- Dill, G.M.; Sammons, R.D.; Feng, P.C.; Kohn, F.; Kretzmer, K.; Mehrsheikh, A.; Bleeke, M.; Honegger, J.L.; Farmer, D.; Wright, D.; et al. Glyphosate: Discovery, Development, Applications, and Properties. In Glyphosate Resistance in Crops and Weeds: History, Development, and Management; Nandula, V.K., Ed.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2010; ISBN 978-0-470-41031-8.

- Vandenberg, L.N.; Blumberg, B.; Antoniou, M.N.; Benbrook, C.M.; Carroll, L.; Colborn, T.; Everett, L.G.; Hansen, M.; Landrigan, P.J.; Lanphear, B.P.; et al. Is it time to reassess current safety standards for glyphosate-based herbicides? Epidemiol. Commun. Health 2017, 71, 613–618, doi:10.1136/jech-2016-208463.

- Duke, S.O. Perspectives on transgenic, herbicide-resistant crops in the USA almost 20 years after introduction. Pest Manag. Sci. 2015, 71, 652–657, doi:10.1002/ps.3863.

- Duke, S.O.; Dayan, F.E. Discovery of new herbicide modes of action with natural phytotoxins. Chem. Soc. Symp. Ser. 2015, 1204, 79–92, doi:10.1021/bk-2015-1204.ch007.

- Benbrook, C.M. Impacts of genetically engineered crops on pesticide use in the U.S.—The first 16 years. Sci. Eur. 2012, 24, 24, doi:10.1186/2190-4715-24-24.

- Heap, I.M. Global perspective of herbicide-resistant weeds. Pest Manag. Sci. 2014, 70, 1306–1315, doi:10.1002/ps.3696.

- Mortensen, D.A.; Egan, J.F.; Maxwell, B.D.; Ryan, M.R. Navigating a critical juncture for sustainable weed management. BioScience 2012, 62, 75–84, doi:10.1525/bio.2012.62.1.12.

- NASS—National Agricultural Statistics Service. U.S. Soybean Industry: Glyphosate Effectiveness Declines. NASS Highlights Nº2014-1. 2014. Available online: https://www.nass.usda.gov/Surveys/Guide_to_NASS_Surveys/Ag_Resource_Management/ARMS_Soybeans_Factsheet/ARMS_2012_Soybeans.pdf (accessed on 14 June 2020).

- Cerdeira, A.L.; Gazziero, D.L.P.; Duke, S.O.; Matallo, M.B. Agricultural impacts of glyphosate-resistant soybean cultivation in South America. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 5799–5807, doi:10.1021/jf102652y.

- Beckie, H.J. Herbicide-resistant weeds: Management tactics and practices. Weed Technol. 2006, 20, 793–814, doi:10.1614/WT-05-084R1.1.

- Beckie, H.J.; Ashworth, M.B.; Flower, K.C. Herbicide Resistance Management: Recent Developments and Trends. Plants 2019, 8, 161, doi:10.3390/plants8060161.

- Moss, S.R. Integrated weed management (IWM): Why are farmers reluctant to adopt non-chemical alternatives to herbicides? Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 1205–1211, doi:10.1002/ps.5267.

- Giesy, J.P.; Dobson, S.; Solomon, K.R. Ecotoxicological risk assessment for Roundup® Rev. Environ. Cont. Toxicol. 2000, 167, 35–120, doi:10.1007/978-1-4612-1156-3_2.

- Borggard, O.K.; Gimsing, A.L. Fate of glyphosate in soil and the possibility of leaching to ground and surface waters: A review. Pest Manag. Sci. 2008, 64, 441–456, doi:10.1002/ps.1512.

- Gillezeau, C.; Van Gerwen, M.; Shaffer, R.M.; Rana, I.; Zhang, L.; Sheppard, L.; Taioli, E. The evidence of human exposure to glyphosate: A review. Health 2019, 18, 2–14, doi:10.1186/s12940-018-0435-5.

- Boobis, A.; Ossendorp, B.C.; Banasiak, U.; Hamey, P.Y.; Sebestyen, I.; Moretto, A. Cumulative risk assessment of pesticide residues in food. Lett. 2008, 180, 137–150, doi:10.1016/j.toxlet.2008.06.004.

- Maeda, H.; Dudareva, N. The shikimate pathway and aromatic amino acid biosynthesis in plants. Rev. Plant Biol. 2012, 63, 73–105, doi:10.1146/annurev-arplant-042811-105439.

- Heap, I. The International Herbicide-Resistant Weed Database. Available online: www.weedscience.org (accessed on 7 December 2020).

- FAO. Management of Herbicide-Resistant Weed Populations: 100 Questions on Resistance; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2008.

- Beckie, H.J.; Heap, I.M.; Smeda, R.J.; Hall, I.M. Screening for herbicide resistance in weeds. Weed Technol. 2000, 14, 428–445.

- Gaines, T.A.; Ward, S.M.; Bukun, B.; Preston, C.; Leach, J.E.; Westra, P. Interspecific hybridization transfers a previously unknown glyphosate resistance mechanism in Amaranthus Evol. Appl. 2012, 5, 29–38, doi:10.1111/j.1752-4571.2011.00204.x.

- Ghanizadeh, H.; Harrington, K.C. Non-target site mechanisms of resistance to herbicides. Rev. Plant Sci. 2017, 36, 24–34, doi:10.1080/07352689.2017.1316134.

- Jugulam, M.; Shyam, C. Non-Target-Site Resistance to herbicides: Recent developments. Plants 2019, 8, 417, doi:10.3390/plants8100417.

- Chueca, C.; Cirujeda, A.; De Prado, R.; Diaz, E.; Ortas, L.; Taberner, A.; Zaragoza, C. Colección de Folletos Sobre Manejo de Poblaciones Resistentes en Papaver, Lolium, Avena y Echinochloa; SEMh Grupo de Trabajo CPRH: Valencia, Spain, 2005.

- Storrie, A. Herbicide Resistance Mechanisms and Common HR Misconceptions. 2006 Grains Research Update for Irrigation Croppers. Brochure. Switzerland, 2006.

- Moss, S.R. Herbicide resistance: New threats, new solutions? In Proceedings of the HGCA CONFERENCE. Arable Crop Protection in the Balance: Profit and the Environment, Grantham, UK 25–26 January 2006.

- Gage, K.L.; Krausz, R.F.; Walters, S.A. Emerging challenges for weed management in herbicide-resistant crops. Agriculture 2019, 9, 180, doi:10.3390/agriculture9080180.

- Reddy Krishna, N.; Jha, P. Herbicide-resistant weeds: Management strategies and upcoming technologies. Indian J. Weed Sci. 2016, 48, 108–111, doi:10.5958/0974-8164.2016.00029.0.

- Boerboom, C.; Owen, M. Facts about Glyphosate-Resistant Weeds; USDA: Washington, DC, USA, 2007.

- Heap, I.; Duke, S.O. Overview of glyphosate-resistant weeds worldwide. Pest Manag. Sci. 2018, 74, 1040–1049, doi:10.1002/ps.4760.

- Owen, M.; Beckie, H.J.; Leeson, J.; Norsworthy, J.K.; Steckel, L.E. Integrated pest management and weed management. Pest Manag. Sci. 2014, 71, 357–376, doi:10.1002/ps.3928.

- Green, J.M. Current state of herbicides in herbicide-resistant crops. Pest Manag. Sci. 2014, 70, 1351–1357, doi:10.1002/ps.3727.

- Lombardo, L.; Coppola, G.; Zelasco, S. New Technologies for Insect-Resistant and Herbicide-Tolerant Plants. Trends Biotechnol. 2016, 34, 49–57, doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2015.10.006.

- Gasser, C.S.; Fraley, R.T. Genetically Engineering Plants for Crop Improvement. Science 1989, 244, 1293–1299, doi:10.1126/science.244.4910.1293.

- Auer, C.; Frederick, R. Crop improvement using small RNAs: Applications and predictive ecological risk assessments. Trends Biotechnol. 2009, 27, 644–651, doi:10.1016/j.tibtech.2009.08.005.

- Runo, S.; Alakonya, A.; Machuka, J.; Sinha, N. RNA interference as a resistance mechanism against crop parasites in Africa: A ‘Trojan horse’ approach. Pest Manag. Sci. 2011, 67, 129–136, doi:10.1002/ps.2052.

- Green, J.M. The benefits of herbicide-resistant crops. Pest Manag. Sci. 2012, 68, 1323–1331, doi:10.1002/ps.3374.

- Espinoza, C.; Schelecheter, R.; Herrera, D.; Torres, E.; Serrano, A.; Medina, C.; Arce-Johnson, P. Cisgenesis and Intragenesis: New tools for Improving Crops. Res. 2013, 46, 323–331, doi:10.4067/S0716-97602013000400003.

- Zhu, T.; Mettenburg, K.; Peterson, D.J.; Tagliani, L.; Baszczynski, C.L. Engineering herbicide-resistant maize using chimeric RNA/DNA oligonucleotides. Biotechnol. 2000, 18, 555–558, doi:10.1038/75435.

- Sun, Y.; Zang, X.; Wu, C.; He, Y.; Ma, Y.; Hou, H.; Guo, X.; Du, W.; Zhaom, Y.; Xia, L. Engineering Herbicide-Resistant Rice Plants through CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Homologous Recombination of Acetolactate Synthase. Plant 2016, 9, 628–631, doi:10.1016/j.molp.2016.01.001.

- Luo, M.; Gilbert, B.; Ayliffe, M. Applications of CRISPR/Cas9 technology for targeted mutagenesis, gene replacement and stacking of genes in higher plants. Plant Cell Rep. 2016, 35, 1493–1450, doi:10.1007/s00299-016-1989-8.

- Han, Y.-J.; Kim, J.-I. Application of CRISPR/Cas9-mediated gene editing for the development of herbicide-resistant plants. Plant Biotechnol. Rep. 2019, 13, 447–457, doi:10.1007/s11816-019-00575-8.

- Hussain, B.; Lucas, S.J.; Budak, H. CRISPR/Cas9 in plants: At play in the genome and at work for crop improvement. Funct. Genom. 2018, 17, 319–328, doi:10.1093/bfgp/ely016.

- Tian, S.; Jiang, L.; Cui, X.; Zhang, J.; Guo, S.; Li, M.; Zhang, H.; Ren, Y.; Gong, G.; Zong, M.; et al. Engineering herbicide-resistant watermelon variety through CRISPR/Cas9-mediated base-editing. Plant Cell Rep. 2018, 37, 1353–1356, doi:10.1007/s00299-018-2299-0.

- Zaidi, S.S.; Mahfouz, M.M.; Mansoor, S. CRISPR-Cpf1: A New Tool for Plant Genome Editing. Trends Plant Sci. 2017, 22, 550–553, doi:10.1016/j.tplants.2017.05.001.

- Kamthan, A.; Chaudhuri, A.; Kamthan, M.; Datta, A. Genetically modified (GM) crops: Milestones and new advances in crop improvement. Appl. Genet. 2016, 129, 1639–1655, doi:10.1007/s00122-016-2747-6.

- Soda, N.; Verma, L.; Giri, J. CRISPR-Cas9 based plant genome editing: Significance, opportunities and recent advances. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2018, 131, 2–11, doi:10.1016/j.plaphy.2017.10.024.

- Ni, Z.; Han, Q.; He, Y.-Q.; Huang, S. Application of genome‐editing technology in crop improvement. Cereal Chem. 2018, 95, 35–48, doi:10.1094/CCHEM-05-17-0101-FI.

- Weston, L.A.; Duke, S.O. Weed and Crop Allelopathy. Rev. Plant Sci. 2003, 22, 367–389, doi:10.1080/713610861.

- Iqbal, J.; Cheema, Z.A.; Mushtaq, M.N. Allelopathic Crop Water Extracts Reduce the Herbicide Dose for Weed Control in Cotton (Gossypium hirsutum). J. Agric. Biol. 2009, 11, 360–366.

- Fujii, Y. Screening and Future Exploitation of Allelopathic Plants as Alternative Herbicides with Special Reference to Hairy Vetch. Crop Prod. 2001, 4, 257–275, doi:10.1300/J144v04n02_09.

- Belz, R.G. Allelopathy in crop/weed interactions—An update. Pest Manag. Sci. 2007, 63, 308–326, doi:10.1002/ps.1320.

- Shirgapure, K.H.; Ghosh, P. Allelopathy a Tool for Sustainable Weed Management. Curr. Res. Int. 2020, 20, 17–25, doi:10.9734/acri/2020/v20i330180.

- Farooq, N.; Abbs, T.; Tanveer, A.; Jabran, K. Allelopathy for Weed Management. In: Co-Evolution of Secondary Metabolites. Reference Series in Phytochemistry; Mérillon, J.M., Ramawat, K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; ISBN 978-3-319-96396-9, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-96397-6_16.

- Muhammad, Z.; Inayat, N.; Majeed, A.; Rehmanullak; Ali, H.; Ullah, K. Allelopathy and Agricultural Sustainability: Implication in weed management and crop protection—An overview. J. Ecol. 2019, 5, 54–61, doi:10.2478/eje-2019-0014.

- Bajwa, A.A.; Khan, M.J.; Bhowmik, P.C.; Walsh, M.; Chauhan, B.S. Sustainable Weed Management. In Innovations in Sustainable Agriculture; Farooq, M., Pisante, M., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019, ISBN 978-3-030-23168-2, doi:10.1007/978-3-030-23169-9_9.

- Kennedy, A.C. Soil Microorganisms for weed management. Crop. Prod. 1999, 2, 123–138, doi:10.1300/9785534.

- Kennedy, A.C.; Kremer, R.J. Microorganisms in Weed Control Strategies. Prod. Agric. 1996, 9, 480–485, doi:10.2134/jpa1996.0480.

- Kremer, R.J. Management of Weed Seed Banks with Microorganisms. Appl. 1993, 3, 42–52, doi:10.2307/1941791.

- Boyetchko, S.M. Principies of Biological Weed Control with Microorganisms. Sci. 1997, 32, 201–205.

- Kremer, R.J.; Caesar, A.J.; Souissi, T. Soilborne microorganisms of Euphorbia are potential biological control agents of the invasive weed leafy spurge. Soil. Ecol. 2006, 32, 27–37, doi:10.1016/j.apsoil.2004.12.009.

- Thrall, P.H.; Oakeshott, J.G.; Fitt, G.; Southerton, S.; Burdon, J.J.; Sheppard, A.; Russell, R.J. Evolution in agriculture: The application of evolutionary approaches to the management of biotic interactions in agro-ecosystems. Appl. 2011, 4, 200–215, doi:10.1111/j.1752-4571.2010.00179.x.

- Devine, M.D.; Shukla, A. Altered target sites as a mechanism of herbicide resistance. Crop Protect. 2000, 19, 881–889, doi:10.1016/S0261-2194(00)00123-X.

- Sibony, M.; Rubin, B. Molecular basis for multiple resistance to acetolactate synthase- inhibitin herbicides and atrazine in Amarantus biotoides (prostrate pigweed). Planta 2003, 216, 1022–1027 and references therein, doi:10.1007/s00425-002-0955-6.

- Li, J.; Smeda, R.J.; Nelson, K.A.; Dayan, F.E. Physiological basis for resistance to diphenyl ether herbicides in common waterhemp (Amaranthus rudis). Weed Sci. 2004, 52, 333–338, doi:10.1614/WS-03-162R.

- Neve, P. Challenges for herbicide resistance evolution and management: 50 years after Harper. Weed Res. 2007, 47, 365–369, doi:10.1111/j.1365-3180.2007.00581.x.

- Yu, Q.; Powles, S. Metabolism-Based Herbicide Resistance and Cross-Resistance in Crop Weeds: A Threat to Herbicide Sustainability and Global Crop Production. Plant Physiol. 2014, 166, 1106–1118, doi:10.1104/pp.114.242750.

- Busi, R.; Vila-Aiub, N.; Beckie, H.J.; Gaines, T.A.; Goggin, D.E.; Kaundun, S.S.; Lacoste, M.; Neve, P.; Nissen, S.J.; Norsworthym, J.K.; et al. Herbicide-resistant weeds: From research and knowledge to future needs. Appl. 2013, 6, 1218–1221, doi:10.1111/eva.12098.

- Busi, R.; Powles, S.B.; Beckie, H.J.; Renton, M. Rotations and mixtures of soil‐applied herbicides delay resistance. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 76, 487–496, doi:1002/ps.5534.

- Vila-Aiub, M.M.; Gundel, P.; Yu, Q.; Powles, S.B. Glyphosate resistance in Sorghum halepense and Lolium rigidum is reduced at suboptimal growing temperatures. Pest Manag. Sci. 2013, 69, 228–232, doi:10.1002/ps.3464.

- Renton, M. Shifting focus from the population to the individual as a way forward in understanding, predicting and managing the complexities of evolution of resistance to pesticides. Pest Manag. Sci. 2013, 69, 171–175, doi:10.1002/ps.3341.

- Alonso, A.; Sánchez, P.; Martínez, J.L. Environmental selection of antibiotic resistance genes. Microbiol. 2001, 3, 1–9, doi:10.1046/j.1462-2920.2001.00161.x.

- Matzrafi, M.; Seiwert, B.; Reemtsma, T.; Rubin, B.; Peleg, Z. Climate change increases the risk of herbicide-resistant weeds due to enhanced detoxification. Planta 2016, 244, 1217–1227, doi:10.1007/s00425-016-2577-4.

- Norsworthy, J.K.; Ward, S.M.; Shaw, D.R.; Llewellyn, R.S.; Nichols, R.L.; Webster, T.M.; Bradley, K.W.; Frisvold, G.; Powles, S.B.; Burgos, N.R.; et al. Reducing the risks of herbicide resistance: Best management practices and recommendations. Weed Sci. 2012, 60, 31–62, doi:10.1614/WS-D-11-00155.1.

- Perotti, V.E.; Larran, A.S.; Palmieri, V.E.; Martinatto, A.K.; Permingeat, H.R. Herbicide resistant weeds: A call to integrate conventional agricultural practices, molecular biology knowledge and new technologies. Plant Sci. 2020, 290, 110255, doi:10.1016/j.plantsci.2019.110255.

- Shaner, D.N. Lessons learned from the history of herbicide resistance. Weed Sci. 2014, 62, 427–431, doi:10.1614/WS-D-13-00109.1.

- Rosset, J.D.; Gulden, R.H. Cultural weed management practices shorten the critical weed-free period for soybean grown in the Northern Great Plains. Weed Sci. 2020, 68, 79–91, doi:10.1017/wsc.2019.60.

- Duary, B. Weed prevention for quality seed production of crops. SATSA Mukhapatra Annu. Tech. Issue 2014, 18, 48–57.

- IAASTD. Agriculture at a Crossroads. International Assessment of Agricultural Knowledge, Science and Technology for Development; Synthsis Report; IAASTD: Washington, DC, USA, 2008.

- Gaba, S.; Fried, G.; Kazakou, E.; Chauvel, B.; Navas, M.-L. Agroecological weed control using a functional approach: A review of cropping systems diversity. Sustain. Dev. 2013, 34, 1–17, doi:10.1007/s13593-013-0166-5.

- Macías, F.A. Allelopathy in the research of natural herbicide models. ACS Symp. Ser. 1995, 582, 310–329, doi:10.1021/bk-1995-0582.ch023.

- Kelton, J.; Price, A.J.; Mosjidis, J. Allelophatic weed suppression through the use of cover crops. In Weed Control; Price, A.J., Ed.; Intech Press: Rijeka, Croatia, 2012; pp. 115–130, and references therein; ISBN 978-953-51-0159-8/978-953-51-5215-6, doi:10.5772/1988.

- Isman, M.B. Botanical insecticides, deterrents and repellents in modern agriculture and an increasingly regulated world. Rev. Entomol. 2006, 51, 45–66, and references therein, doi:10.1146/annurev.ento.51.110104.151146.

- Macías, F.A.; Molinillo, J.M.G.; Varela, R.M.; Galindo, J.C.G. Allelopathy, a natural alternative for week control. Pest Manag. Sci. 2007, 63, 327–384, doi:10.1002/ps.1342.

- Tabaglio, V.; Gavazzi, C.; Schulz, M.; Marocco, A. Alternative weed control using the allelopathic effect of natural bezoxazinoids from rye mulch. Sustain. Dev. 2008, 28, 397–401, doi:10.1051/agro:2008004.

- Khalid, S.; Ahmand, T.; Shad, R.A. Use of allelopathy in agriculture. Asian J. Plant Sci. 2002, 1, 292–297, doi:10.3923/ajps.2002.292.297.

- Vyvyan, J.R. Allelochemicals as leads for new herbicides and agrochemicals. Thetrahedron 2002, 58, 1631–1646, doi:10.1016/S0040-4020(02)00052-2.

- Soltys, D.; Krasuska, U.; Bogatek, R.; Gniazdowska, A. Allelochemicals as bioherbicides: Present and perspectives. In Herbicides: Current Research and Cases Studies in Use; Price, A., Kelton, J., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2013; ISBN 978-953-51-1112-2/978-953-51-5378-8, doi:10.5772/56743.

- Balah, M.A. Formulation of prospective plant oils derived micro-emulsions for herbicidal activity. Plant Prot. Path. 2013, 4, 911–926.

- Wang, Y.; Zhao, R.; Yu, L.; Zhang, Y.; He, Y.; Yao, J. Evaluation of cinnamon essential oil microemulsion and its vapor phase for controlling postharvest gray mold of pears (Pyrus pyrifolia). Sci. Food Agric. 2014, 30, 1000–1004, doi:10.1002/jsfa.6360.

- Massoud, A.; Manal, M.A.; Osman, A.Z.; Magdy, I.E.M.; Abdel-Rheim, K.H. Eco-Friendly Nano-emulsion Formulation of Mentha piperita Against Stored Product Pest Sitophilus oryzae Adv. Crop Sci. Tech. 2018, 6, 1000404, doi:10.4172/2329-8863.1000404.

- Rakmai, J.; Cheirsilp, B.; Cid, A.; Torrado-Agrasar, A.; Mejuto, J.C.; Simal-Gandara, J. Encapsulation of Essential Oils by Cyclodextrins: Characterization and Evaluation. In Cyclodextrin: A Versatile Ingredient; Arora, P., Dhingra, N., Eds.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2018; pp. 264–290; ISBN 978-1-78923-068-0/978-1-83881-379-6, doi:10.5772/intechopen.69187.

- Rakmai, J.; Cheirsilp, B.; Mejuto, J.C.; Simal-Gándara, J.; Torrado-Agrasar, A. Antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of encapsulated guava leaf oil in hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin. Crops Prod. 2018, 111, 219–225, doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2017.10.027.

- Rakmai, J.; Cheirsilp, B.; Cid, A.; Torrado-Agrasar, A.; Simal-Gandara, J.; Mejuto, J.C. Encapsulation of yarrow essential oil in hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin: Physiochemical characterization and evaluation of bio-efficacies. CyTA J. Food. 2017, 15, 409–417, doi:10.1080/19476337.2017.1286523.

- Rakmai, J.; Cheirsilp, B.; Mejuto, J.C.; Torrado-Agrasar, A.; Simal-Gandara, J. Physico-chemical characterization and evaluation of bio-efficacies of black pepper essential oil encapsulated in hydroxypropyl-beta-cyclodextrin. Food Hydrocol. 2017, 65, 157–164, doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2016.11.014.

- Webber III, C.L.; Shrefler, J.W.; Brandenberger, L.P. Organic Weed Control. In Herbicides: Environmental Impact Studies and Management Approaches; Alvarez-Fernandez, R., Ed.; Intech Open: London, UK, 2012; pp. 185–189, ISBN 978-953-307-892-2/978-953-51-5181-4, doi:10.5772/1206.

- Singh, N.; Chaput, L.; Villoutreix, B.O. Virtual screening web servers: Designing chemical probes and drug candidates in the cyberspace. Bioinform. 2020, bbaa034, doi:10.1093/bib/bbaa034.

- Kraehmer, H.; Laber, B.; Rosinger, C.; Schulz, A. Herbicides as weed control agents: State of the art: I. Weed control research and safener technology: The path to modern agriculture. Plant Physiol. 2014, 166, 1119–1131, doi:10.1104/pp.114.241901.

- Angeline, L.G.; Carpanese, G.; Cioni, P.L.; Morelli, I.; Macchia, M.; Flamini, G. Essential oils from Mediterranean Lamiaceae as weed germination inhibitors. Agric. Food Chem. 2003, 51, 6158–6164, doi:10.1021/jf0210728.

- Tworkoski, T. Herbicide effects of essential oils. Weed Sci. 2002, 50, 425–431, doi:10.1614/0043-1745(2002)050[0425:HEOEO]2.0.CO;2.

- Dayan, F.E.; Cantrell, C.L.; Duke, S.O. Natural products in crop protection. Med. Chem. 2009, 17, 4022–4034, and references therein, doi:10.1016/j.bmc.2009.01.046.

- Santana, O.; Cabrera, R.; Giménez, C.; González-Coloma, A.; Sánchez-Vioque, R.; de los Mozos-Pascual, M.; Rodríguez-Conde, M.F.; Laserna-Ruiz, I.; Usano-Alemany, J.; Herraiz, D. Chemical and biological profiles of the essential oils from aromatic plants of agro industrial interest in Castilla-La Mancha (Spain). Grasas Aceites Int. J. Fats Oils 2012, 63, 214–222, doi:10.3989/gya.129611.

- Mucciarelli, M.; Camusso, W.; Bertea, C.M.; Maffei, C.M. Effect of (+)-pulegone and other oil components of Mentha piperita on cucumber respiration. Phytochemistry 2001, 57, 91–98, doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(00)00393-9.

- Verdeguer, M.; Catañeda, L.G.; Torre-Pagan, N.; Llorens-Molina, J.A.; Carrubba, A. Control of Erieron bonariensis with Thymbra captata, Mentha piperitam Eucaliptus camaldulensis and Santolina chamaecyparissus essential oils. Molecules 2020, 25, 562, doi:10.3390/molecules25030562.

- Vasilakoglou, I.; Dhima, K.; Wogiatzi, E.; Eleftherohorinos, I.; Lithourgidis, A. Herbicidal potential of essential oils of oregano or marjoram (Origanum) and Basil (Ocimun basilicum) on Echinochloa crus-galli (L.) P. Beauv. and Chenopodium album L. weeds. Allelopat. J. 2007, 20, 297–306.

- García-Rellán, D.; Verdeguer, M.; Salamone, A.; Blázquez, M.A.; Boira, H. Chemical composition, herbicidal and antifungal activity of Satureja cuneifolia essential oils from Spain. Prod. Commun. 2016, 11, 841–844.

- Zhang, J.; An, M.; Wu, H.; Liu, L.L.; Stanton, R. Chemical composition of essential oils of four Eucalyptus species and their phytotoxicity on silverleaf nightshade (Solanum elaeagnifloium) in Australia. Plant Growth Reg. 2012, 68, 231–237, doi:10.1007/s10725-012-9711-5.

- Maaloul, A.; Verdeguer-Sancho, M.M.; Oddo, M.; Saadaoui, E.; Jebri, M.; Michalet, S.; Dijoux-Franca, M.G.; Mars, M.; Romdhane, M. Effect of Short and Long Term Irrigation with Treated Wastewater on Chemical Composition and Herbicidal Activity of Eucalyptus camaldulensis Essential Oils. Not. Bot. Horti Agrobot. Cluj Napoca 2019, 47, 1374–1381, doi:10.15835/nbha47411374.

- Barbosa, J.C.A.; Filomen, C.A.; Teixeira, R.R. Chemical variability and biological activities of Eucalyptus Essential oils. Molecules 2016, 21, 1671, doi:10.3390/molecules2112671.

- Ben Ghnaya, A.; Hamrouni, L.; Ahouses, I.; Hanana, M.; Romane, A. Study of allelopathic effects of Eucalyptus erythrocorys crude extracts against germination and seedling growth of weeds and wheat. Nat. Prod. Res. 2016, 30, 2058–2064, doi:10.1080/14786419.2015.1108973.

- Ismail, A.; Lamia, H.; Mohsen, H.; Bassem, J. Herbicidal potential of essential oils from three Mediterranean trees on different weeds. Bioact. Comp. 2013, 8, 3–12, doi:10.2174/157340712799828197.

- Verdeguer, M.; Blazquez, M.A.; Boira, H. Chemical composition and herbicidal activity of the essential oil from a Cistus ladanifer population from Spain. Prod. Res. 2012, 26, 1602–1609, doi:10.1080/14786419.2011.592835.