| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Charalampos Proestos | + 3887 word(s) | 3887 | 2020-04-28 04:08:29 | | | |

| 2 | Charalampos Proestos | Meta information modification | 3887 | 2020-05-03 15:53:34 | | |

Video Upload Options

Phenolic acids comprise a group of natural compounds that are present in a wide range of herbs and other species of the plant kingdom. This work focuses on the most common natural occurring phenolic acids (caffeic, carnosic, ferulic, gallic, p-coumaric, rosmarinic, vanillic) and gives a summary of their recently reported health related effects that mainly link to their antioxidant properties. A number of in vitro and in vivo animal studies has been screened by the authors who report on most important research findings on each individual phenolic acid (or natural mixtures of them) while also formulating a number of conclusions and recommendations for future work in this scientific field.

1. Introduction

The phenolic acids offer an important group of powerful natural compounds that can be extracted from various plant sources, including edible herbs and well known botanicals [1, 2]. A large number of studies have focused on the radical scavenging capacity of phenolics and their subsequent beneficial effects against the development of cancer, cardiovascular diseases and other health disorders (such as skin problems, inflammations, bacterial infections etc.) [3,4].

A body of research evidence focuses on the activity of various phenolic acids against cancer and the main mechanisms by which they may exert their effects such as: scavenging of free radicals, induction of enzymes, DNA damage repair, cell proliferation and apoptosis [5,6]. Rosa et al. (2016) [7] supported that phenolic acids have been a prime source for the treatment of various forms of cancer, with focus on colon cancer in human colon adenocarcinoma cells.

Furthermore, Vinayagam et al. (2016) [8] examined the potential of phenolic acids to improve glucose and lipid profiles linked pathologic conditions (diabetes, cardiovascular diseases etc.). A diet rich in phenolic acids has been also reported to protect against certain allergies and slow down the development of Alzheimer disease [9].

This work focuses on the most common natural occurring phenolic acids, including caffeic, carnosic, ferulic, gallic, p-coumaric, rosmarinic, and vanillic. The authors have reviewed a large number of clinical studies investigating into the health effects of phenolic acids and their mixtures extracted from natural plant sources. For each individual phenolic acid a quick reference to their important natural sources is first provided, followed by a more detailed discussion on the latest literature evidence concerning the health and biochemical properties.

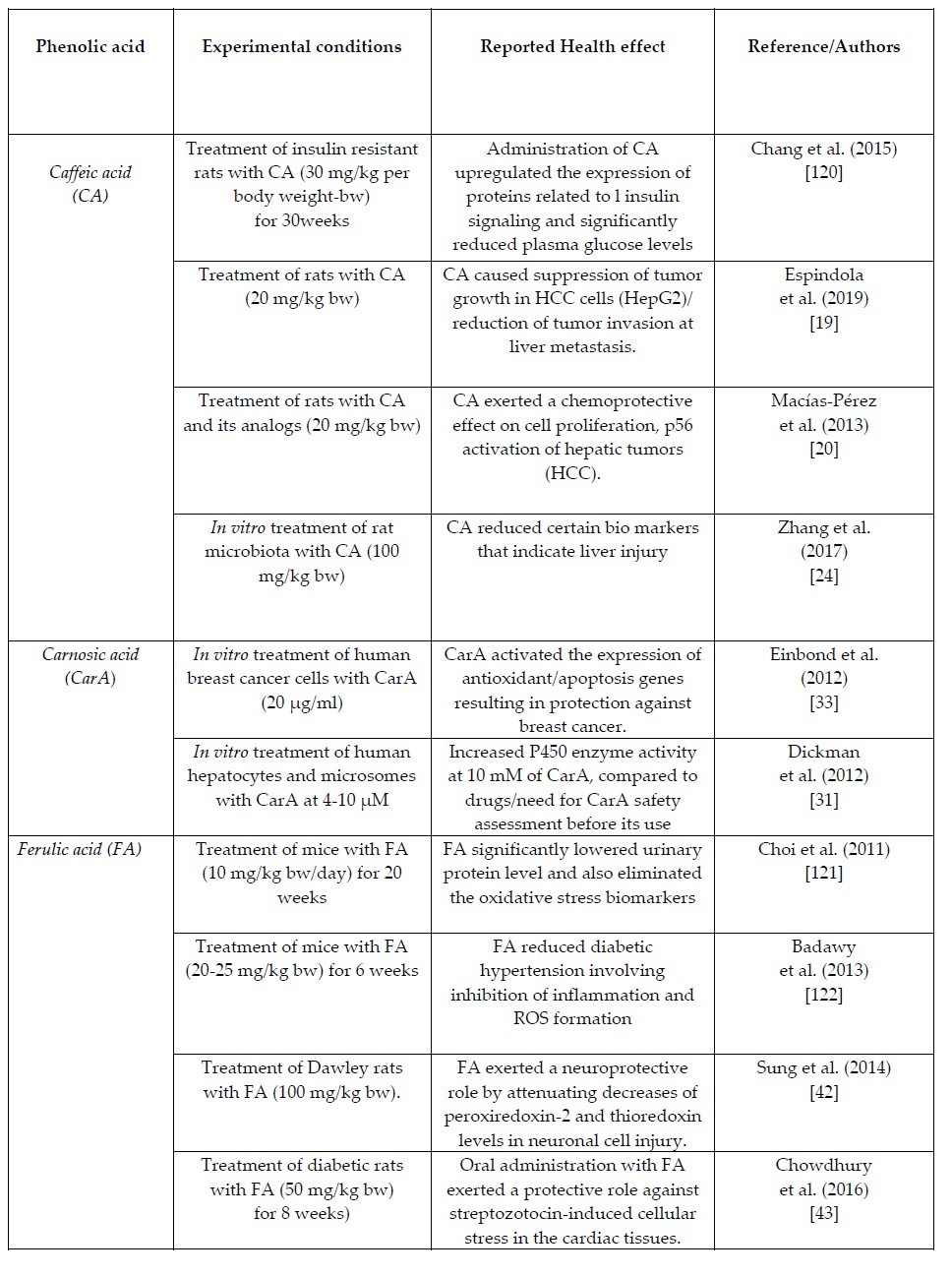

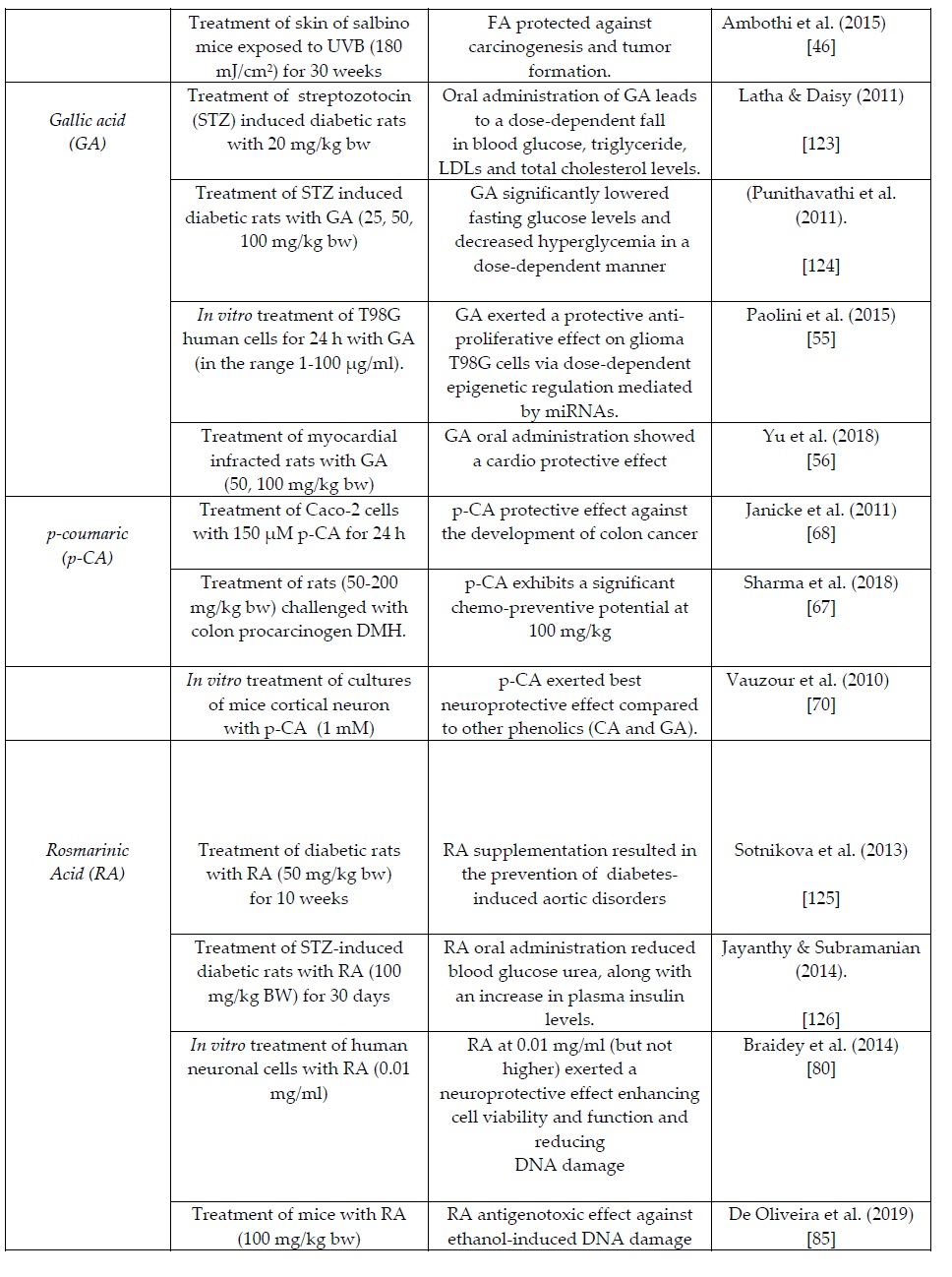

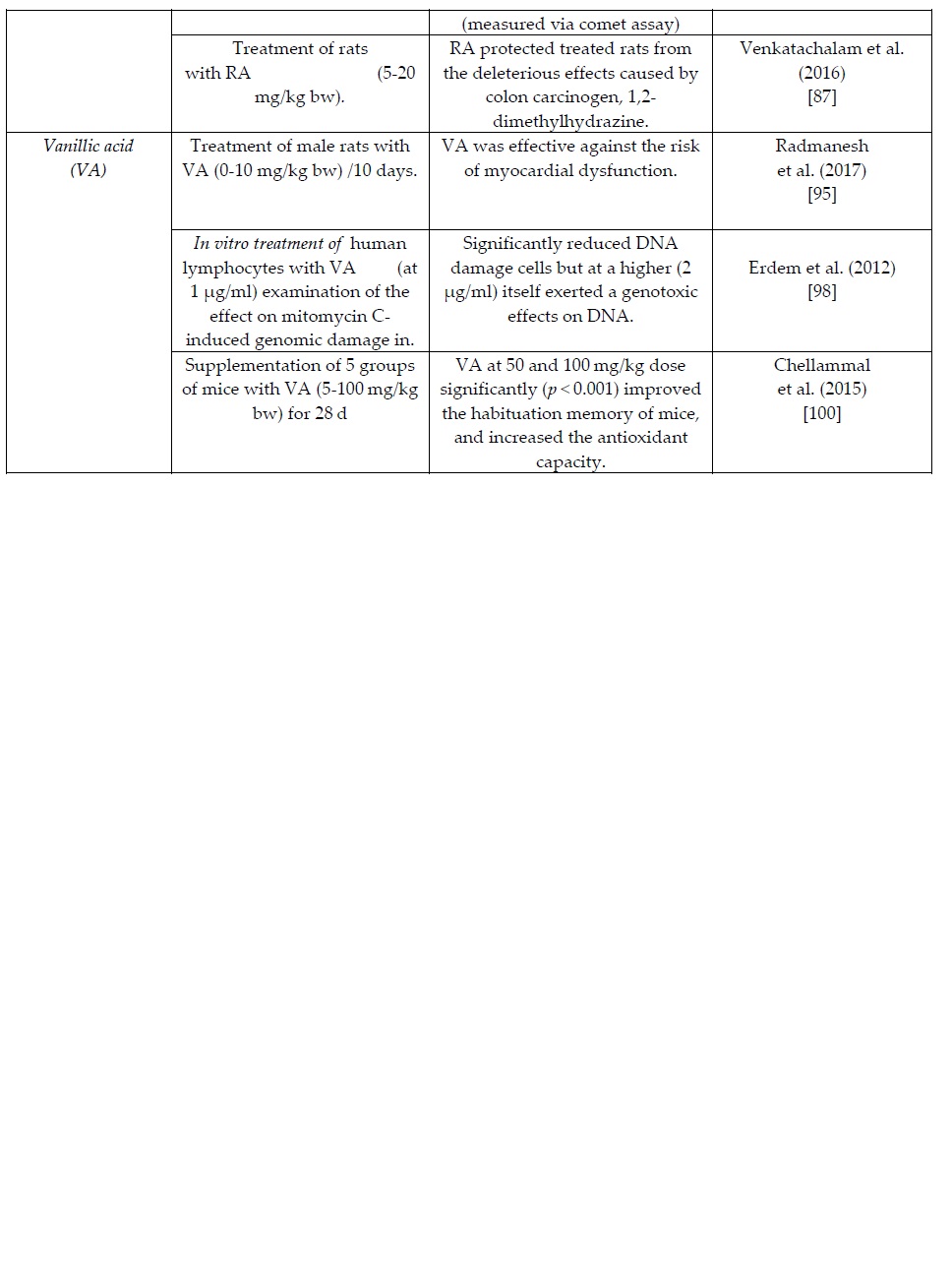

The summary Table 1 provides an overview of recent in vitro and in vivo clinical studies on the health/biochemical properties of the examined phenolic acids. More specific information per phenolic acid is presented in the following sections.

2. Caffeic acid (CA) CA is a hydroxycinnamic acid structurally composed of both phenolic and acrylic functional groups, the derivatives of which are trans in nature [10,11]. Ιt is found at high levels in some herbs, especially in the South American herb yerba mate (1.5 g/kg) [12], and thyme (1.7 mg/kg), [13]. In fruits (such as berries, apples and pears) CA was quantified in high amounts, representing together with p-coumaric acid 75-100% of the total hydroxycinnamic acids [14].

Further to its well established antioxidant and anti-aging activities, CA has been reported to own strong antimicrobial properties and protect against dermal diseases [15]. De Oliveira et al. (2012) [16] designed a drug delivery system based on o/w emulsions with CA containing microparticles, developed in order to ensure a prolonged CA release in the target cells and thereby treat the folliculitis skin disease. Similarly, Paulo and Santos (2019) [17] examined how incorporation of caffeic–ethyl cellulose microparticles in skin care products can offer anti-aging protection. Furthermore, a body of recent research evidence has demonstrated that caffeic acid phenyl ester (CAPE) is a natural compound with anticancer activities. The chemical structure of CA (presence of free phenolic hydroxyls) is believed to strongly account for its antioxidant capacities that, in turn, link to certain anti-carcinogenic properties [18]. Dietary supplementation of rats, with CA and CAPE (5 mg/kg body wt subcutaneous or 20 mg/kg oral), was shown to inhibit tumor growth in HCC cells (HepG2) and reduce the tumor invasion at a liver metastatic site [19]. Another clinical study [20] has reported a clear chemo protective effect of CAPE and its analogs (20 mg/kg body wt) against lipid peroxidation and subsequent cell proliferation of hepatic tumors (HCC) in rats.

Guan et al. (2019) [21] used sucrose fatty acid ester to nano-encapsulate CAPE in aqueous propylene glycol with a temperature-cycle method and reported that nano-encapsulation enhanced cytotoxicity of CAPE against colon cancer HCT-116, and breast cancer MCF-7 cells. Another recent medical study [22] reported clear inhibitory effects of CAPE derivatives against acetylcholinesterase, an enzyme linked with the development of Alzheimer’s disease. CA and its derivatives, such as CAPE, have been reported to act against colon cancer through their cytotoxic to tumors but not to normal cells [23]. In addition, Zhang et al. 2017 [24] examined the action of CA (100 mg/kg) on structural changes caused by HCC in the rat microbiota. The authors concluded that this phenolic compound reduces certain bio markers that indicate liver injury (among other alanine, transaminase, aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, total bile acid and total cholesterol).

3. Carnosic acid (CarA)

CarA is a labdane-type diterpene present in plant species of the Lamiaceae family, such as rosemary and common salvia species [25]. CarA is commonly found in the dried leaves of sage in 1.5 to 2.5% concentration [26]. CarA is used as a preservative in food and non-food products, e.g. toothpaste, mouthwash and chewing gum, since it is endowed with antioxidative and antimicrobial properties [27].

Since its first extraction from various natural sources (e.g. Salvia and Rosmarinus species) and given its well reported functional and antioxidant properties, CarA has been used in a range of cosmetic and pharmaceutical applications [28,29]. Several researchers have focused on the liver protective effect of CarA. In an interesting placebo clinical trial [30] a male ob/ob mice (model for NAFLD-non alcoholic fat liver disease) followed a diet with CarA for 5 weeks and compared to placebo experienced weight loss and reduced visceral adiposity. The authors concluded that CarA could be considered for the development of new drugs against the NAFLD liver syndrome. Dickmann et al. (2012) [31] explored the hepatotoxicity potential of CarA (at varying concentrations of 4-10 μM) in primary human hepatocytes and microsomes. While CarA did not exhibit any significant time-dependent enzyme inhibition at 4 mM, it even increased enzyme activity at 10 μM, compared with Phenobarbital and Rifampicin drugs. According to the authors, the results indicate potential CarA interaction with drugs, thereby a need for its appropriate safety assessment before its further use as a weight loss supplement.

Bahri et al., 2016 [32] noted that CarA can have a protective effect against chronic neurodegenerative conditions, like Parkinson's disease, via a mechanism that links to the transcriptional activation of antioxidant Nrf2/ARE pathway.

Einbond et al. (2012) [33], after in vitro experiments in human breast cancer cells, have observed that treatment with CarA at 20 μg/ml resulted in the prevention of ER-negative breast cancer via an activation of expression of antioxidant and apoptosis genes. A more recent study by Solomonov et al. (2018) [34] demonstrated a significant anti-inflammatory effect of CarA combined with astaxanthin and a lycopene-rich tomato extract in a nutrient supplementation.

However, Raes et al. (2015) [26] did not report any effect of CarA, against lipid and protein oxidation in an in vitro simulated gastric digestion model.

4. Ferulic acid (FA)

FA is a phenolic acid commonly found in the seeds of coffee, apple, artichoke, peanut, and orange [35]. Flaxseed has been reported as the richest natural source of FA glucoside (4.1 ± 0.2 g/kg) [36]. According to various researchers [37,38], black beans contain FA at an average concentration of 0.8 g/kg. In addition, FA can be found in Brassica vegetables and tomatoes [14].

Over the last few years, a number of clinical studies have demonstrated that FA can exert in vivo antioxidant effects by scavenging free radicals and enhancing the cell stress response through the up-regulation of cytoprotective systems [39,40]. Based on its antioxidant and anti-inflammation functions, FA is widely considered as a phenolic compound with well documented protective actions against many pathologic conditions (e.g. types of cancer, cardiovascular diseases, diabetes mellitus and skin problems) [111]. Sgarbossa et al. (2015) [41] reviewed the health benefits of FA and noted its protective role against neurotoxicity based on a number of in vitro and in vivo animal clinical studies. Sung et al. (2014) [42] treated Dawley rats (male, 210-230 g) with FA (100 mg/kg body wt) and reported a clear neuroprotective role. The above indicated findings recommend the use of FA for drugs development against neurodegenerative diseases, although a few questions are still open before its clinical development and application in patients.

Chowdhury et al. (2016) [43] performed a clinical study that involved oral administration of diabetic rats with FA (at a dose of 50 mg/kg body wt, orally for eight weeks). The authors concluded a protective role of FA against streptozotocin-induced cellular stress in the cardiac tissues. Baeza et al. (2017) [44] reported a strong inhibitory effect of dihydroferulic acid against in vitro platelet activation.

Ambothi et al. (2014) [45] concluded that FA (in the concentration range 10-40 μg/ml) can prevent the ultraviolet-B radiation (290-320 nm) induced oxidative DNA damage in human dermal fibroblasts. The same researchers conducted another clinical study [46] reporting that FA protected against carcinogenesis and tumor formation induced via chronic UVB exposure (180 mJ/cm2 for 30 weeks) in the skin of Swiss albino mice. Russo et al. (2017) [47] conducted a population-based case-control study in South Italy to examine any association between dietary phenolic acids consumption and prostate cancer. From a sample of 2044 individuals, 118 histopathological-verified prostate cancer cases were collected, and multivariate logistic regression showed that both CA and FA were associated with reduced risk of this cancer type.

5. Gallic acid (GA)

GA (also known as 3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoic acid) is the main phenolic acid in tea [48] but also found in high amounts in chestnuts and several berries [13]. It is encountered in a number of land plants, such as the parasitic plant Cynomorium coccineum, the aquatic plant Myriophyllum spicatum, and the blue-green alga Microcystis aeruginosa [49,50].

Over the last few years, a body of research evidence had reported cardio protective, neuroprotective, and anticancer properties of GA and gallates that are mostly attributed to their antioxidative properties against the reactive oxygen species (ROS) signaling networks [51]. Sourani et al. (2016) [52] reported that GA inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in lymphoblastic leukemia cell line. In a very recent study [53] the ability of GA to potentiate the anti-cancer effects of chemotherapeutic drugs (e.g. Paclitaxel, Carboplatin) was examined in human HeLa cells. The authors reported that a Paclitaxel/GA combination could represent a promising alternative with lower side effects for Paclitaxel/Carboplatin combinations in treatment of cervical cancer. Recent pharmacokinetic human and animal clinical studies were based on Chinese GA based patented medicines but further investigation is needed on the GA kinetic profile after dietary supplementation before drawing any conclusion for its efficacy against pathological conditions [54]. Paolini et al. (2015) [55] performed a study to explore the potential of GA as a promising new anticancer drug. The authors treated T98G human glioblastoma cell lines for 24 h with increasing concentrations of GA (ranging from 1 to 100 μg/ml). According to the results, GA exerts a protective or an anti-proliferative effect on glioma T98G cells via dose-dependent epigenetic regulation mediated by miRNAs.

Yu et al. (2018) [56] contacted a clinical study on myocardial infarcted rats with an oral administration of GA monohydrate at a dose of 50 and 100 mg/kg body wt. The authors observed that myocardial infarction could modify the pharmacokinetic process of GA and thereby determine its potential activity. Similarly, Nwokocha et al. [57] concluded that GA can present negative chronotropic and inotropic effects in isoproterenol induced myocardial damage.

6. p-Coumaric acid (p-CA)

A large number of natural plants sources have been reported to be rich in p-CA such as fungi, peanuts, navy beans, tomatoes, carrots, basil and garlic [58]. p-CA is abundant in most fruits (especially pears and berries) and cereals [14, 59], as well ell as in honey at a concentration range 1.7-4.7 mg/kg [60]. In addition, a few researchers noted that p-CA is present in extracts derived from Amaranth leaves and stem at a concentration range of 28-44 mg/kg [61,62].

p-CA has been reported to decrease the peroxidation of low density lipoproteins (LDL) and exert anti-mutagenesis, anti-genotoxicity and anti-microbial activities [63]. Very recently, Ferreira et al. (2019) [64] gave a literature overview of certain biochemical properties of CA (including radical scavenging and tumor suppression activities) that link to its claimed pharmacological effects. Boo (2019) [65] has highlighted the anti-melanogenic effects of p-CA by focusing on its inhibitory action against melanin synthesis as observed in human epidermal melanocytes. Neog and Rasool [66] supported that dietary p-CA could intervene in the osteoclast formation and thereby alleviate the effect of rheumatoid arthritis, a finding also supported by Trisha (2016) [58].

Janicke et al. (2011) [67] treated Caco-2 cells with 150 μM p-CA for 24 h, and noticed a protective effect against the development of colon cancer by retarding the cell cycle progression. Ιn addition, Sharma et al. (2017) [68] conducted a study to evaluate the chemo-preventive potential of p-CA in rats challenged with the colon specific procarcinogen DMH. According to the results, p-CA presented a concentration-dependent anti-carcinogenic effect since it acted more efficiently at a dose of 100 mg/kg body wt, compared to 50 mg/kg body wt. Amalan et al. (2016) [69] reported that p-CA inhibited the development of oxidative stress by increasing the endogenous antioxidant capacity (level of glutathione-GSH) in the livers of diabetic rats. In addition, Vauzour et al. (2010) [70] compared the neuroprotection capacities of various phenolic compounds in primary cultures of mice cortical neuron. The authors concluded a stronger protective effect of p-CA at 1 mM concentration than those of CA and GA. Very recently, Sunitha et al. (2018) [71] reported that p-CA mediated the protection of H9c2 cells from Doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity.

7. Rosmarinic acid (RA)

RA is an ester of caffeic acid, present as the main phenolic component in several members of the Lamiaceae family including among others: Rosmarinus officinalis, Origanum spp., Perilla spp., and Salvia officinialis [72,73]. A few researchers reported RA as the main phenolic acid of various culinary herbs (oregano, thyme sage and rosemary) in concentrations varying between 0,05 and 26 g/kg dry weight [74,75]. Additionally, the results of Tsimogiannis et al. [76] indicate an amount of 19.5 g/kg in the leaves of pink savory (Satureja thymbra L.).

Yang et al. (2013) [77] reported the health protective effects of RA on high mobility group box1 (HMGB1) protein-induced inflammation that mediates responses to infection and injury cases. Similarly, Tsung et al. (2013) [78] observed that RA can suppresses Propionibacterium acnes–induced inflammatory responses. Concerning the anti-inflammatory mechanism, Ku et al. (2013) [79] observed that RA down-regulates endothelial protein C receptor shedding, in vitro and in vivo. Braidy et al. (2016) [80] investigated whether RA (0.01-0.1 mg/ml) can protect against CTX-mediated toxicity in primary human neurons. According to the results pre-treatment with RA at 0.01 mg/ml (but not higher) exerted a neuroprotective effect, generating significant decrease in CTX-mediated extracellular LDH activity, NAD decline and DNA damage, compared to CTX treated cells alone.

Nunes et al. (2017) [81] noted that RA displays several health beneficial effects (including antimicrobial and anti-carcionogenic properties) the magnitude of which depends greatly on both its intake and bioavailability. Hossan et al. (2014) [82] have more specifically focused on the anticarcinogenic properties of RA proposing various mechanisms of anticancer activity including antioxidant actions along with proliferation and apoptosis of cancer cells.

Stansbury (2014) [73] summarized the clinical trials that have demonstrated RA activities against allergic immunoglobulin and inflammatory responses of polymorphonuclear leukocytes, thereby being effective in the treatment of allergic disorders. Alagawany et al. (2019) [83] have also reviewed the mode of action, and health benefits of RA. Domitrović et al. (2013) [84] reported that RA can protect against acute liver damage in intoxicated mice by exerting certain antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and anti-apoptotic activities. More recently, De Oliveira et al. (2019) [85] examined the protective effects of RA against ethanol-induced DNA damage in mice and reported a clear antigenotoxic capacity in a concentration of 100 mg/kg body wt by using the comet assay. Luno et al. (2014) [86] concluded that RA at 105 μM concentration improves function and in vitro fertilising ability of boar sperm, by inhibiting oxidative stress during cryopreservation. Furthermore, Venkatachalam et al. (2016) [87] investigated into the mode and molecular mechanisms that govern the chemoprotective action of RA against colon cancer in rats. The authors reported that supplementation with RA (5-20 mg/kg body wt) protected treated rats from the deleterious effects caused by the colon carcinogenic 1,2-dimethylhydrazine.

8. Vanillic Acid (VA) VA is a dihydroxybenzoic acid derivative commonly used as a flavoring agent. It is found in several fruits, olives, and cereal grains (e.g. whole wheat), as well as in wine, beer and cider [88,89]. Kim et al. (2019) [90] performed an identification of the main phenolic constituents in potatoes samples (Solanum tuberosum L.) and quantified VA at a concentration between 0.02 and 0.04 g/kg. VA was also found in fruit extract of the the açaí palm plant (Euterpe oleracea) [91] and was identified by Zhao et al [92] in the root of Angelica sinensis (an herb indigenous to China) at concentrations between 1.1 and 1.3 g/kg.

VA has been reported to confer certain health beneficial effects, via antioxidative, anti-mutagenic, anti-cancer, anti-inflammatory, and neuroprotective activities [93,94].

In a recent study [95], male rats (separated in groups of 10) were supplemented with varying concentrations of VA (0-10 mg/kg body wt) for a period of 10 days. The results have shown a clear effect of VA against the risk of myocardial dysfunction. Similarly, Dianat et al. (2014) [96] demonstrated the effectiveness of VA against lipid peroxidation, indicated by malondialdehyde (MDA) reduction, and endogenous antioxidant enzymes improvement, in isolated rat hearts exposed to ischemia-reperfusion. Kim et al. (2010) [97] following a clinical trial in rats reported beneficial effects of VA in the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Erdem et al. (2012) [98] examined the potential effect of VA against mitomycin C-induced genomic damage in human lymphocytes in vitro. Interestingly, VA (at 1 µg/ml) significantly reduced DNA damage cells but at a higher concentration (2 µg/ml) exerted a genotoxic effect on DNA. On the contrary, Krga et al. [99] (2018) reported that VA at 2 μM did not significantly decrease biomarkers of platelet activation development of cardiovascular diseases.

In a clinical trial by Chellammal et al. (2015) [100], five groups of mice were treated as control or active groups supplemented with VA in the concentration range 5-100 mg/kg for 28 days. The results showed that VA at 50 and 100 mg/kg dose significantly (p < 0.001) improved the habituation memory, decreased the AChE, corticosterone, and increased the antioxidant capacity of the mice. Furthemore, Yemis et al. (2011) [101] reported a pH dependent antimicrobial effect of VA that was found to inhibit the growth and heat resistance of Cronobacter bacterial species, a conclusion that could lead to the use of VA for new food storage applications.

9. Natural botanical preparations (mixtures of phenolic acids)

Nature has generously offered a wide range of herbs (e.g. thyme, oregano, rosemary, sage, mint) that are rich in many phenolic compounds with strong antioxidant biochemical and anti-inflammatory properties [102, 103] including protection of DNA from oxidative damage [104]. More specifically, bael (Aegle marmelos) flower (rich in p-CA, CA and VA) and tulsi (Ocimum tenuiflorum) seeds (rich in GA and p-CA) have been reported to present a strong antioxidant character again DNA damage [105, 106].

Findings from recent nutritional intervention studies with natural extracts rich in phenolic acids suggest that they can exert a clear cardio-protective effect through modulations of platelet function [107]. Padmanabhan and Geetha (2015) [108] reported a clear hypo-lipidemic and anti-obesity effect of hydro-alcoholic fruit extract of avocado (particularly rich in GA and VA) in rats fed with high fat diet (co-administered with 100 mg/kg body wt of HFEA for 14 weeks).

Extensive research has been conducted in the last decade about rosemary extracts that are particularly rich in RA and CarA. Chkhikvishvili et al. (2013) [109] demonstrated that a rosemary extract (RE) can protect Jurkat cells from oxidative stress induced by hydrogen peroxide. Very recently, Pérez-Sánchez et al. (2019) [110] investigated the antitumor activity of RE obtained by using supercritical fluid extraction, through its capacity to inhibit various signatures of cancer progression and metastasis. Ulbricht et al. (2010) [111] has published an evidence-based systematic review on RE by examining various aspects of their health properties including also information on their adverse effects and toxicology. In a recent study, Sánchez Salcedo et al. (2015) [112] demonstrated that RE can exert an in vivo anti tumor action through a reactive oxygen species-initiated cell death.

Andrade et al. (2018) [113] reported a clear protective role of RE in preventing colds, rheumatism, and pain of muscles and joints.

De Oliveira et al. (2019) [85] reviewed the in vivo and in vitro studies of R. officinalis highlighting the therapeutic and prophylactic effects of RE on some physiological disorders caused by various biochemical agents. Moore et al. (2016) [114] reviewed the phytochemical biological activities and anti-carginogenic properties of R. officinalis.

Moreover, p-CA rich methanolic extracts of Amaranthus spinosus and of Amaranthus caudatus L. were shown to possess significant central and peripheral anti-nociceptive potential and anti-inflammatory activity, in mouse model [72]. Jeong et al. (2017) [115] observed clear therapeutic effects of polyphenolic mixtures (containing among others GA, p-CA and ellagic acid) against cell lung cancer. Hydroxycinnamic acid derivatives of mulberry fruits were reported to increase the production of reactive oxygen species production by acting as pro-oxidants and hence killing the cancer cells [116]. Hilbig et al. (2017) [117] reported that an aqueous extract from pecan nut (particularly rich in GA, CA and VA) showed clear inhibitory effects against breast cancer cell line MCF-7, as well as against tumor growth in Balb-C mice. Simin et al. (2019) [118] provided an overview of the beneficial biological activities of less known wild onions (A. sect. Codonoprasum), which are particularly rich in the common phenolic acids. The same group [119] has concluded that a methanolic extract of small yellow onion (Allium flavum), particularly rich in FA, p-CA, CA, and VA, can exert selective inhibitory action towards cervix epithelioid carcinoma and colon adenocarcinoma cells.

10. Conclusions and future challenges

This analysis presented a summary of the most recent in vitro and in vivo clinical (mainly animal) studies on phenolic acids. Based on the most important findings on the biochemical activities of phenolic acids, the authors have drawn the following conclusions along with a few recommendations for future investigation in this field:

· There is a sufficient body of latest research evidence to support that the examined phenolic acids possess biochemical properties of importance against a wide range of pathogenic conditions including: cancer, bacterial infections, cardiovascular, inflammatory and neurodegenerative diseases. Given, though, that the current knowledge is based on model animal studies, further clinical investigation on dietary supplementation of phenolics in humans would be required in order to consolidate their health protective effects.

· Recent clinical studies based on natural botanical extracts have demonstrated that such natural preparations -that comprise mixtures of various phenolic acids-could also exert clear health properties. The strong antioxidant and biochemical potential of these natural plant extracts may more specifically link to synergistic effect of their individual phenolic compounds.

· Although a few phenolic acids are well known as efficient bioactive dietary ingredients, their pharmacokinetics and metabolic properties are not fully elucidated yet. This is a factor that limits their current use and therapeutic potential and requires further clinical investigations to support and optimize their future use in nutritional and pharmaceutical applications.

· Future challenges may also include the development of nano-based emulsion systems to enable the delivery of functional bio-constituents (e.g. phenolic acids) and thereby promote their applications in innovative dietary supplements or even drug formulations.

Table 1. Summary table of of recent in vitro and in vivo clinical animal studies on the health/biochemical properties of the natural occurring phenolic acids

[1][2][3][4][5][6][7][8][9][10][11][12][13][14][15][16][17][18][19][20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35][36][37][38][39][40][41][42][43][44][45][46][47][48][49][50][51][52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71][72][73][74][75][76][77][78][79][80][81][82][83][84][85][86][87][88][89][90][91][92][93][94][95][96][97][98][99][100][101][102][103][104][105][106][107][108][109][110][111][112][113][114][115][116][117][118][119][120][121][122][123][124][125][126][127]

References

- Κiokias, S.; Varzakas, T. Activity of flavonoids and beta-carotene during the auto-oxidative deterioration of model food oil-in water emulsions. Food Chem. 2014, 150, 280-286.

- Liudvinaviciute, D.; Rutkaite,R.; Bendoraitiene, J.; Klimaviciute. R. Thermogravimetric analysis of caffeic and rosmarinic acid containing chitosan complexes. Carbohyd. Polym. 2019, 222, 115003.

- Kiokias, S. (2019). Antioxidant effects of vitamins C, E and provitamin A compounds as monitored by use of biochemical oxidative indicators linked to atherosclerosis and carcinogenesis. International Journal of Nutritional Research, 1, 01-13.

- Kiokias, S., Proestos, C & Oreopoulou,V (2018). Phenolic acids of plant origin- A review on their antioxidant activity in vitro (o/w emulsion systems) along with their in vivo health biochemical properties. Foods, 9, 534, 1-22.

- Manuja, R.; Sachdeva, S.; Jain, A.; Chaudhary, J. A comprehensive review on biological activities of p-hydroxy benzoic acid and its derivatives. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2013, 22, 109-115.

- Rosa Ls; Silva Nja; Soares Ncp; Monteiro Mc; Teodoro Aj; Anticancer Properties of Phenolic Acids in Colon Cancer – A Review. Journal of Nutrition & Food Sciences 2016, 6, , 10.4172/2155-9600.1000468.

- Rosa, L.-S.; Silva, N.-J.; Soares, N.-C.; Monteiro, M.-C.; Teodoro, A.-J. Anticancer properties of phenolic acids in colon cancer – A review. J. Nutr Food Sci. 2016, 6, 2.

- Vinayagam Ramachandran; Muthukumaran Jayachandran; Baojun Xu; Antidiabetic Effects of Simple Phenolic Acids: A Comprehensive Review. Phytotherapy Research 2015, 30, 184-199, 10.1002/ptr.5528.

- Fereidoon Shahidi; Judong Yeo; Bioactivities of Phenolics by Focusing on Suppression of Chronic Diseases: A Review. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2018, 19, 1573, 10.3390/ijms19061573.

- Dalbem, L.; Costa Monteiro, C.-M.; Anderson J.-T. Anticancer properties of hydroxycinnamic acids - A Review. Canc. Clinic. Oncol. 2012, 1(2), 109-121.

- Bojić, M.; Haas, V.-S.; Šarić, D,; Maleš, Z. Determination of flavonoids, phenolic acids, and xanthines in Mate tea (Ilex paraguarJ Agric Food Chem. 2011, 59, 5523-7.

- Berté, K.-A.; Beux, M.-R. ; Spada, P.-K. ; Salvador, M. ; Hoffmann-Ribani, R. Chemical composition and antioxidant activity of yerba-mate (Ilex paraguariensis A.St.-Hil.,

- Ana Žugić; Sofija Đorđević; Ivana Arsić; Goran Marković; Jelena Živković; Slobodanka Jovanovic; Vanja Tadić; Antioxidant activity and phenolic compounds in 10 selected herbs from Vrujci Spa, Serbia. Industrial Crops and Products 2014, 52, 519-527, 10.1016/j.indcrop.2013.11.027.

- Bento-Silva, A.; Koistinen, V. M.; Mena, P.; Bronze, M. R.; Hanhineva, K.; Sahlstrøm, S.; Aura, A.-M. Factors affecting intake, metabolism and health benefits of phenolic acids: do we understand individual variability? Eur. J. Nutr. 2019, 1-19iensis St.-Hil.). J. Anal. Meth. Chem. 2013, 6, 1-6.

- C. Magnani; V. L. B. Isaac; M. A. Correa; Hérida Regina Nunes Salgado; Caffeic acid: a review of its potential use in medications and cosmetics. Analytical Methods 2014, 6, 3203-3210, 10.1039/c3ay41807c.

- Nânci C.D. De Oliveira; Merielen S. Sarmento; Emilene Nunes; Carem M. Porto; Darlan P. Rosa; Silvia Bona; Graziella Rodrigues; Norma P. Marroni; Patrícia Pereira; Jaqueline Nascimento Picada; Alexandre B.F. Ferraz; Flavia Thiesen; Juliana Da Silva; Rosmarinic acid as a protective agent against genotoxicity of ethanol in mice. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2012, 50, 1208-1214, 10.1016/j.fct.2012.01.028.

- Filipa Paulo; Lúcia Santos; Microencapsulation of caffeic acid and its release using a w/o/w double emulsion method: Assessment of formulation parameters. Drying Technology 2018, 37, 950-961, 10.1080/07373937.2018.1480493.

- Maria Gaglione; Gaetano Malgieri; Severina Pacifico; Valeria Severino; Brigida D’Abrosca; Luigi Russo; Antonio Fiorentino; Anna Messere; Synthesis and Biological Properties of Caffeic Acid-PNA Dimers Containing Guanine. Molecules 2013, 18, 9147-9162, 10.3390/molecules18089147.

- Espíndola,M.; Ferreira, R.-G.; Mosquera Narvaez, L.-E.; Rocha Silva Rosario, A.-C.; et al. Chemical and pharmacological aspects of caffeic acid and its activity in hepatocarcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 541.

- Hongyu Zhao; Et Al. Et Al.; Isoxazole Carboxylic Acids as Protein Tyrosine Phosphatase 1B (PTP1B) Inhibitors.. ChemInform 2005, 36, , 10.1002/chin.200514226.

- Yongguang Guan; Huaiqiong Chen; Qixin Zhong; Nanoencapsulation of caffeic acid phenethyl ester in sucrose fatty acid esters to improve activities against cancer cells. Journal of Food Engineering 2019, 246, 125-133, 10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2018.11.008.

- Gießel, J.-M.; Loesche, A.; Csuk, R. Caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE)-derivatives act as selective inhibitors of acetylcholinesterase2010. Eur. J. Med. Chem. 2019, 177, 259-268.

- Koru, F.; Avcu, M.; Tanyuksel, A.; Ural, U. R.; Araz, E.; Sener K. Cytotoxic effects of caffeic acid phenethyl ester (CAPE) on the human multiple myeloma cell line. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2009, 39, 863–870.

- Zhan Zhang; Di Wang; Shanlei Qiao; Xinyue Wu; Shuyuan Cao; Li Wang; Xiaojian Su; Lei Li; Metabolic and microbial signatures in rat hepatocellular carcinoma treated with caffeic acid and chlorogenic acid. Scientific Reports 2017, 7, 4508, 10.1038/s41598-017-04888-y.

- Margot Loussouarn; Anja Krieger-Liszkay; Ljubica Svilar; Antoine Bily; Simona Birtić; Michel Havaux; Carnosic Acid and Carnosol, Two Major Antioxidants of Rosemary, Act through Different Mechanisms. Plant Physiology 2017, 175, 1381-1394, 10.1104/pp.17.01183.

- Katleen Raes; Evelyne H.A. Doolaege; Steven Deman; Els Vossen; Stefaan De Smet; Effect of carnosic acid, quercetin and α-tocopherol on lipid and protein oxidation in anin vitrosimulated gastric digestion model. International Journal of Food Sciences and Nutrition 2015, 66, 216-221, 10.3109/09637486.2014.959900.

- Zhan-Jun Li; Fengjian Yang; Lei Yang; Yuan-Gang Zu; Comparison of the antioxidant effects of carnosic acid and synthetic antioxidants on tara seed oil.. Chemistry Central Journal 2018, 12, 37, 10.1186/s13065-018-0387-4.

- Caiyu Lei; Xiangyi Tang; Mingshun Chen; Hualei Chen; Shujuan Yu; Alpha-tocopherol-based microemulsion improving the stability of carnosic acid and its electrochemical analysis of antioxidant activity. Colloids and Surfaces A: Physicochemical and Engineering Aspects 2019, 580, , 10.1016/j.colsurfa.2019.123708.

- Birtić, S.; Dussort, P.; Pierre F.-X .; Bily, A.-C.;, Roller, M. Carnosic acid. Phytochemistry. 2015, 115, 9-19.

- Claire Greenhill; Carnosic acid could be a new treatment option for patients with NAFLD or the metabolic syndrome. Nature Reviews Gastroenterology & Hepatology 2011, 8, 122-122, 10.1038/nrgastro.2011.9.

- Dickmann, L.-J.; VandenBrin, B.-M.; Lin, Y.-S. In Vitro Hepatotoxicity and Cytochrome P450 Induction and Inhibition Characteristics of Carnosic Acid, a Dietary Supplement with Antiadipogenic Properties Drug.Metab.Dispos. 2012, 40, 1263-1267.

- A. Dubis; M. V. Zamaraeva; L. Siergiejczyk; O. Charishnikova; Vadim Shlyonsky; Ferutinin as a Ca2+complexone: lipid bilayers, conductometry, FT-IR, NMR studies and DFT-B3LYP calculations. Dalton Transactions 2015, 44, 16506-16515, 10.1039/c4dt03892d.

- Linda Saxe Einbond; Hsan-Au Wu; Ryota Kashiwazaki; Kan He; Marc Roller; Tao Su; Xiaomei Wang; Sarah Goldsberry; Carnosic acid inhibits the growth of ER-negative human breast cancer cells and synergizes with curcumin. Fitoterapia 2012, 83, 1160-1168, 10.1016/j.fitote.2012.07.006.

- Yulia Solomonov; Nurit Hadad; Rachel Levy; The Combined Anti-Inflammatory Effect of Astaxanthin, Lyc-O-Mato and Carnosic Acid In Vitro and In Vivo in a Mouse Model of Peritonitis. Journal of Nutrition & Food Sciences 2018, 8, 1-7, 10.4172/2155-9600.1000653.

- Naresh Kumar; Vikas Pruthi; Potential applications of ferulic acid from natural sources.. Biotechnology Reports 2014, 4, 86-93, 10.1016/j.btre.2014.09.002.

- John Flanagan; Antoine Bily; Yohan Rolland; Marc Roller; Lipolytic Activity of Svetol®, a Decaffeinated Green Coffee Bean Extract. Phytotherapy Research 2013, 28, 946-948, 10.1002/ptr.5085.

- Mojica, L.; Meyer,A.; Berhow, M.; González, E.; Bean cultivars (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) have similar high antioxidant capacity, in vitro inhibition of α-amylase and α-glucosidase while diverse phenolic composition and concentration. Food Res. Intern. 2015, 69, 38-48.

- Devanand L. Luthria; Marcial A. Pastor-Corrales; Phenolic acids content of fifteen dry edible bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) varieties. Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2006, 19, 205-211, 10.1016/j.jfca.2005.09.003.

- Cesare Mancuso; Rosaria Santangelo; Ferulic acid: Pharmacological and toxicological aspects. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2014, 65, 185-195, 10.1016/j.fct.2013.12.024.

- Raul Zamora-Ros; V Knaze; I Romieu; A Scalbert; N Slimani; F Clavel-Chapelon; M Touillaud; F Perquier; Guri Skeie; D Engeset; Elisabete Weiderpass; I Johansson; R Landberg; H B Bueno-De-Mesquita; Sabina Sieri; Giovanna Masala; P H M Peeters; V Grote; María José Sánchez; A Barricarte; P Amiano; Francesca Crowe; Esther Molina-Montes; K-T Khaw; M V Argüelles; Anne Tjønneland; J Halkjær; M S De Magistris; Fulvio Ricceri; R Tumino; E Wirfält; U Ericson; Kim Overvad; A Trichopoulou; V Dilis; P Vidalis; H Boeing; J Forster; Elio Riboli; Carlos A González; Impact of thearubigins on the estimation of total dietary flavonoids in the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) study. European Journal of Clinical Nutrition 2013, 67, 779-782, 10.1038/ejcn.2013.89.

- Sgarbossa, A.; Giacomazza, D.; Martadi, Carlo. Ferulic acid: A hope for Alzheimer’s disease therapy from plants. Nutrients, 2015, 7, 5764-5782.

- Jin-Hee Sung; Sang-Ah Gim; Phil-Ok Koh; Ferulic acid attenuates the cerebral ischemic injury-induced decrease in peroxiredoxin-2 and thioredoxin expression. Neuroscience Letters 2014, 566, 88-92, 10.1016/j.neulet.2014.02.040.

- Chowdhury, S.;, Ghosh ,S.;, Rashid, K.;, Sil, P.-C. Deciphering the role of ferulic acid against streptozotocin-induced cellular stress in the cardiac tissue of diabetic rats. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2016, 97, 187-198.

- Gema Baeza; Eva-Maria Bachmair; Sharon Wood; R. Mateos; Laura Bravo; Baukje De Roos; The colonic metabolites dihydrocaffeic acid and dihydroferulic acid are more effective inhibitors of in vitro platelet activation than their phenolic precursors. Food & Function 2017, 8, 1333-1342, 10.1039/c6fo01404f.

- RajendraPrasad Nagarajan; Kanagalakshmi Ambothi; Ferulic acid prevents ultraviolet-B radiation induced oxidative DNA damage in human dermal fibroblasts. International Journal of Nutrition, Pharmacology, Neurological Diseases 2014, 4, 203, 10.4103/2231-0738.139400.

- Kanagalakshmi Ambothi; Nagarajan Rajendra Prasad; Agilan Balupillai; Ferulic acid inhibits UVB-radiation induced photocarcinogenesis through modulating inflammatory and apoptotic signaling in Swiss albino mice. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2015, 82, 72-78, 10.1016/j.fct.2015.04.031.

- Giorgio I. Russo; Daniele Campisi; Marina Di Mauro; Federica Regis; Giulio Reale; Marina Marranzano; Rosalia Ragusa; Tatiana Solinas; Massimo Madonia; Sebastiano Cimino; Giuseppe Morgia; Dietary Consumption of Phenolic Acids and Prostate Cancer: A Case-Control Study in Sicily, Southern Italy. Molecules 2017, 22, 2159, 10.3390/molecules22122159.

- Pandurangan, A.-K.; Mohebali, N.; Norhaizan, M.-E, Looi, C.-Y. Gallic acid attenuates dextran sulfate sodium-induced experimental colitis in BALB/c mice". Drug Design. Develop.Therapy. 2015, 9, 3923–34.

- Liu, Y; Carver, J.-A.; Calabrese, A.-N.; Pukala, T.-L. Gallic acid interacts with α-synuclein to prevent the structural collapse necessary for its aggregation. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA) – Prot. Proteo. 2014, 1844, 1481–1485.

- Paolo Zucca; A. Rosa; Carlo Tuberoso; Alessandra Piras; Andrea C. Rinaldi; Enrico Sanjust; M. Assunta Dessi; Antonio Rescigno; Evaluation of Antioxidant Potential of “Maltese Mushroom” (Cynomorium coccineum) by Means of Multiple Chemical and Biological Assays. Nutrients 2013, 5, 149-161, 10.3390/nu5010149.

- Kosuru R. Y.; Roy A.; Das S. K.; Bera S. Gallic acid and gallates in human health and disease: do mitochondria hold the key to success? Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 10, 62.

- Sourani, Z.-M.; Pourgheysari, B.-P.; Beshkar, P.-M.; Shirzad, H.-P.; Shirzad, M.-M. Gallic acid inhibits proliferation and induces apoptosis in lymphoblastic leukemia cell line (C121). Iran J. Med. Sci. 2016, 41, 525–30.

- Nora Aborehab; Nada Osama; Effect of Gallic acid in potentiating chemotherapeutic effect of Paclitaxel in HeLa cervical cancer cells.. Cancer Cell International 2019, 19, 154, 10.1186/s12935-019-0868-0.

- Zhihai Li; Xuekui Yu; Progress towards revealing the mechanism of herpesvirus capsid maturation and genome packaging. Protein & Cell 2020, null, 1-2, 10.1007/s13238-020-00716-8.

- E. Capelli; R. Nano; M. Civallero; M. Ceroni; 5-39-04 Cytokines and adhesion molecules evaluation in central nervous system tumors. Journal of the Neurological Sciences 1997, 150, S331, 10.1016/s0022-510x(97)86520-3.

- Yu,Z.; Song, F.; Jin, Y.-C.; Zhang, W.-M.; Zhang, Y. et al. Comparative Pharmacokinetics of Gallic Acid After Oral Administration of Gallic Acid Monohydrate in Normal and Isoproterenol-Induced Myocardial Infarcted Rats. Front Pharmacol. 2018, 6, 328.

- Chukwuemeka Nwokocha; Javier Palacios; Mario J. Simirgiotis; Jemesha Thomas; Magdalene Nwokocha; Lauriann Young; Rory K. Thompson; Fredi Cifuentes; Adrián Paredes; Rupika Delgoda; Aqueous extract from leaf of Artocarpus altilis provides cardio-protection from isoproterenol induced myocardial damage in rats: Negative chronotropic and inotropic effects. Journal of Ethnopharmacology 2017, 203, 163-170, 10.1016/j.jep.2017.03.037.

- Trisha, S. Role of hesperdin, luteolin and coumaric acid in arthritis management: A Review. Inter. J. Phys. Nutr. Phys. Educ. 2018, 3, 1183-1186.

- Kehan Pei.; Ou, J.; Huanga, J.; Oua. S. Coumaric acid and itsconjugates: dietary sources, pharmacokinetic properties and biological activities. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2016, 96, 2952–296.

- Nesovic, M.; Tosti, T.; Trifkovi, J.; Baosic, R.; Blagojevic,S.; Ignjatovic, L., Tesic, Z Physicochemical analysis and phenolic profile ofpolyfloral and honeydew honey from Montenegro. RSC-Adv. 2020,10, 2462.

- Kavita Peter; Puneet Gandhi; Rediscovering the therapeutic potential of Amaranthus species: A review. Egyptian Journal of Basic and Applied Sciences 2017, 4, 196-205, 10.1016/j.ejbas.2017.05.001.

- Paweł Paśko; Mieczysław Sajewicz; S. Gorinstein; Z. Zachwieja; Analysis of selected phenolic acids and flavonoids inAmaranthus cruentusandChenopodium quinoaseeds and sprouts by HPLC. Acta Chromatographica 2008, 20, 661-672, 10.1556/achrom.20.2008.4.11.

- Kehan Pei; Juanying Ou; Junqing Huang; Shiyi Ou; p-Coumaric acid and its conjugates: dietary sources, pharmacokinetic properties and biological activities. Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2016, 96, 2952-2962, 10.1002/jsfa.7578.

- Paula Scanavez Ferreira; Francesca Damiani Victorelli; Bruno Fonseca-Santos; Marlus Chorilli; A Review of Analytical Methods for p-Coumaric Acid in Plant-Based Products, Beverages, and Biological Matrices. Critical Reviews in Analytical Chemistry 2018, 49, 21-31, 10.1080/10408347.2018.1459173.

- Yong Chool Boo; p-Coumaric Acid as An Active Ingredient in Cosmetics: A Review Focusing on its Antimelanogenic Effects.. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 275, 10.3390/antiox8080275.

- Manoj Neog; Mahaboobkhan Rasool; Targeted delivery of p-coumaric acid encapsulated mannosylated liposomes to the synovial macrophages inhibits osteoclast formation and bone resorption in the rheumatoid arthritis animal model. European Journal of Pharmaceutics and Biopharmaceutics 2018, 133, 162-175, 10.1016/j.ejpb.2018.10.010.

- Birgit Janicke; Cecilia Hegardt; Morten Krogh; Gunilla Önning; Björn Åkesson; Helena M. Cirenajwis; Stina Oredsson; The Antiproliferative Effect of Dietary Fiber Phenolic Compounds Ferulic Acid andp-Coumaric Acid on the Cell Cycle of Caco-2 Cells. Nutrition and Cancer 2011, 63, 611-622, 10.1080/01635581.2011.538486.

- Sharada H. Sharma; David Raj Chellappan; Prabu Chinnaswamy; Sangeetha Nagarajan; Protective effect of p-coumaric acid against 1,2 dimethylhydrazine induced colonic preneoplastic lesions in experimental rats. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2017, 94, 577-588, 10.1016/j.biopha.2017.07.146.

- Venkatesan Amalan; Natesan Vijayakumar; Dhananjayan Indumathi; Arumugam Ramakrishnan; Antidiabetic and antihyperlipidemic activity of p -coumaric acid in diabetic rats, role of pancreatic GLUT 2: In vivo approach. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2016, 84, 230-236, 10.1016/j.biopha.2016.09.039.

- David Vauzour; Giulia Corona; Jeremy P.E. Spencer; Caffeic acid, tyrosol and p-coumaric acid are potent inhibitors of 5-S-cysteinyl-dopamine induced neurotoxicity. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 2010, 501, 106-111, 10.1016/j.abb.2010.03.016.

- Mary Chacko Sunitha; Radhakrishnan Dhanyakrishnan; Bhaskara Prakashkumar; Kottayath Govindan Nevin; p -Coumaric acid mediated protection of H9c2 cells from Doxorubicin-induced cardiotoxicity: Involvement of augmented Nrf2 and autophagy. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy 2018, 102, 823-832, 10.1016/j.biopha.2018.03.089.

- Antigoni Oreopoulou; Eleni Papavassilopoulou; Haido Bardouki; Manolis Vamvakias; Andreas Bimpilas; Vassiliki Oreopoulou; Antioxidant recovery from hydrodistillation residues of selected Lamiaceae species by alkaline extraction. Journal of Applied Research on Medicinal and Aromatic Plants 2018, 8, 83-89, 10.1016/j.jarmap.2017.12.004.

- Jill Stansbury; Rosmarinic Acid as a Novel Agent in the Treatment of Allergies and Asthma*. Journal of Restorative Medicine 2014, 3, 121-126, 10.14200/jrm.2014.3.0109.

- Anna Vallverdú-Queralt; Jorge Regueiro; Miriam Martínez-Huélamo; José Fernando Rinaldi De Alvarenga; Leonel Neto Leal; Rosa María Lamuela-Raventós; A comprehensive study on the phenolic profile of widely used culinary herbs and spices: Rosemary, thyme, oregano, cinnamon, cumin and bay. Food Chemistry 2014, 154, 299-307, 10.1016/j.foodchem.2013.12.106.

- Alexander Yashin; Yakov Yashin; Xiaoyan Xia; Boris V. Nemzer; Antioxidant Activity of Spices and Their Impact on Human Health: A Review. Antioxidants 2017, 6, 70, 10.3390/antiox6030070.

- Tsimogiannis, D.; Choulitoudi, E.; Bimpilas, A.; Mitropoulou, G.; Kourkoutas, Y.; Oreopoulou, V. Exploitation of the biological potential of Satureja thymbra essential oil and distillation by-products J. Appl. Res. Med. Aroma.t Plants 2016, 4, 12-20.

- Eun-Ju Yang; Sae-Kwang Ku; Wonhwa Lee; Sangkyu Lee; Taeho Lee; Kyung-Sik Song; Jong-Sup Bae; Barrier protective effects of rosmarinic acid on HMGB1-induced inflammatory responses in vitro and in vivo. Journal of Cellular Physiology 2013, 228, 975-982, 10.1002/jcp.24243.

- Tsung-Hsien,T.; Chuang, L.-Te.; Lien, T.-J.; Liing, Y.-R.; Chen, W.-Y.; Tsai, P.-J Rosmarinus officinalis extract suppresses Propionibacterium acnes–induced inflammatory responses. J. Med. Food. 2013, 16, 324–333.

- Sae-Kwang Ku; Eun-Ju Yang; Kyung-Sik Song; Jong‐Sup Bae; Rosmarinic acid down-regulates endothelial protein C receptor shedding in vitro and in vivo. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2013, 59, 311-315, 10.1016/j.fct.2013.06.003.

- Braidy, N.; Matin, A.; Rossi, F.; Chinain, M.; Laurent, D.; Guillemin, G. J.

- Neuroprotective effects of rosmarinic acid on ciguatoxin in primary human neurons. Neurotox. Res. 2014, 25, 226–234.

- Sara Nunes; Raquel Madureira; Débora A. Campos; Bruno Sarmento; Ana M. P. Gomes; Manuela Pintado; Flávio Reis; Ana Raquel Madureira; Maria Manuela Pintado; Therapeutic and Nutraceutical Potential of Rosmarinic Acid - Cytoprotective Properties and Pharmacokinetic Profile. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 2015, null, 00-00, 10.1080/10408398.2015.1006768.

- Hossan, M.-S.; Rahman, S.; Anwarul Bashar, A.-.; Jahan, R.; Al-Nahain, A.; Rahmatullah, M Rosmarinic acid: a review of its anticancer action. World J. Pharmac. Sci. 2014, 3, 57–70.

- P. A. Desingu; Kuldeep Dhama; Y. S. Malik; R. K. Singh; May Newly Defined Genotypes XVII and XVIII of Newcastle Disease Virus in Poultry from West and Central Africa Be Considered a Single Genotype (XVII)?. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 2016, 54, 2399-2399, 10.1128/JCM.00667-16.

- Robert Domitrović; Marko Škoda; Vanja Vasiljev Marchesi; Olga Cvijanovic; Ester Pernjak Pugel; Maja Bival Štefan; Rosmarinic acid ameliorates acute liver damage and fibrogenesis in carbon tetrachloride-intoxicated mice. Food and Chemical Toxicology 2013, 51, 370-378, 10.1016/j.fct.2012.10.021.

- Zineb Choukairi; Tahar Hazzaz; Mustapha Lkhider; José Manuel Ferrandez; Taoufiq Fechtali; Effect of Salvia Officinalis L. and Rosmarinus Officinalis L. leaves extracts on anxiety and neural activity.. Bioinformation 2019, 15, 172-178, 10.6026/97320630015172.

- Luño,V.; Gil, L.; Olaciregui, M.; González, N.; Jerez, R.-A.; de Blas, I. Rosmarinic acid improves function and in vitro fertilising ability of boar sperm after cryopreservation. Cryobiology. 2014, 69, 157-162.

- Karthikkumar Venkatachalam; Sivagami Gunasekaran; Nalini Namasivayam; Biochemical and molecular mechanisms underlying the chemopreventive efficacy of rosmarinic acid in a rat colon cancer. European Journal of Pharmacology 2016, 791, 37-50, 10.1016/j.ejphar.2016.07.051.

- Siriamornpun, S.; Kaewseejan N. Quality, bioactive compounds and antioxidant capacity of selected climacteric fruits with relation to their maturity Sci. Hortic. 2017, 221, 33-42.

- European Medicinal Agency. Assessment report on Angelica sinensis(Oliv.) Diels, radix. Committee on Herbal Medicinal Products (HMPC). 2013. EMA/HMPC/614586/2012 (link: https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/documents/herbal-report/final-assessment-report-angelica-sinensis-oliv-diels-radix-first-version_en.pdf)

- Jinhee Kim; Soon Yil Soh; Haejin Bae; Sang-Yong Nam; Antioxidant and phenolic contents in potatoes (Solanum tuberosum L.) and micropropagated potatoes. Applied Biological Chemistry 2019, 62, 17, 10.1186/s13765-019-0422-8.

- Pacheco-Palencia, L.-A.; Mertens, T.-S.; Talcott, S.-T. Chemical composition, antioxidant properties, and thermal stability of a phytochemical enriched oil from Acai (Euterpe oleracea Mart.). J. Agric. Food Chem. 2008, 56, 4631–4636.

- Chengke Zhao; Yuan Jia; Fachuang Lu; Angelica Stem: A Potential Low-Cost Source of Bioactive Phthalides and Phytosterols. Molecules 2018, 23, 3065, 10.3390/molecules23123065.

- Mathew, S.; Halamaa, A.; Kadera, S.-A.; Choea, M.; Mohney, R.-P.; Malekc J.-A, Suhrea, K. Metabolic changes of the blood metabolome after a date fruit challenge. J. Func. Foods. 2018, 49, 267–276.

- F. F. Rasulov; SCHEME PLANTING OF SWEET PEPPER IN SUMMER TERM OF CULTIVATION. Vegetable crops of Russia 2018, null, 45-46, 10.18619/2072-9146-2017-5-45-46.

- Radmanesh, E.; Dianat, M.; Badavi, M.; Goudarzi, .; Mard, A. The cardio protective effect of vanillic acid on hemodynamic parameters, malondialdehyde, and infract size in ischemia-reperfusion isolated rat heart exposed to PM. Iran J. Basic Med. Sci. 2017, 20, 760–768.

- Mahin Dianat; Gholam Reza Hamzavi; Mohammad Badavi; Alireza Samarbafzadeh; Effects of Losartan and Vanillic Acid Co-Administration on Ischemia-Reperfusion-Induced Oxidative Stress in Isolated Rat Heart. Iranian Red Crescent Medical Journal 2014, 16, , 10.5812/ircmj.16664.

- Su-Jin Kim; Min-Cheol Kim; Jae-Young Um; Seung-Heon Hong; The Beneficial Effect of Vanillic Acid on Ulcerative Colitis. Molecules 2010, 15, 7208-7217, 10.3390/molecules15107208.

- Merve Guler Erdem; Nilüfer Çinkılıç; Özgür Vatan; Dilek Yılmaz; Deniz Bagdas; Rahmi Bilaloĝlu; Genotoxic and Anti-Genotoxic Effects of Vanillic Acid Against Mitomycin C-Induced Genomic Damage in Human Lymphocytes In Vitro. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention 2012, 13, 4993-4998, 10.7314/apjcp.2012.13.10.4993.

- Irena Krga; Nevena Vidovic; Dragan Milenkovic; Aleksandra Konić Ristić; Filip Stojanovic; Christine Morand; Maria Glibetić; Effects of anthocyanins and their gut metabolites on adenosine diphosphate-induced platelet activation and their aggregation with monocytes and neutrophils. Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 2018, 645, 34-41, 10.1016/j.abb.2018.03.016.

- Chellammal, J.; Singh, H.; Kakalij, R.-M.; Kshirsagar, R-P.; Kumar, B.-H.; Komakula, S.-B.; Diwan, P.M. Cognitive effects of vanillic acid against streptozotocin-induced neurodegeneration in mice. Pharmac. Biol. 2015, 53, 630-636.

- Gökçe Polat Yemiş; Franco Pagotto; Susan Bach; Pascal Delaquis; Effect of Vanillin, Ethyl Vanillin, and Vanillic Acid on the Growth and Heat Resistance of Cronobacter Species. Journal of Food Protection 2011, 74, 2062-2069, 10.4315/0362-028x.jfp-11-230.

- Alois Jungbauer; Svjetlana Medjakovic; Anti-inflammatory properties of culinary herbs and spices that ameliorate the effects of metabolic syndrome. Maturitas 2012, 71, 227-239, 10.1016/j.maturitas.2011.12.009.

- Prabhat K.K. Pandey; George C. Schatz; Time-dependent Hartree—Fock calculations of surface-enhanced Raman intensities. H2 adsorbed on a model Li cluster. Chemical Physics Letters 1982, 88, 193-197, 10.1016/0009-2614(82)83366-6.

- Andreia Fernandes; José Luiz Mazzei; H. Evangelista; Mônica Regina Da Costa Marques Calderari; E.R.A. Ferraz; Israel Felzenszwalb; Protection against UV-induced oxidative stress and DNA damage by Amazon moss extracts. Journal of Photochemistry and Photobiology B: Biology 2018, 183, 331-341, 10.1016/j.jphotobiol.2018.04.038.

- F. Shahidi; Indicators for evaluation of lipid oxidation and off-flavor development in food. Developments in Food Science 1998, 40, 55-68, 10.1016/s0167-4501(98)80032-0.

- H. Yu; Y. Niu; Y. Hu; D. Du; Photosynthetic response of the floating-leaved macrophyte Nymphoides peltata to a temporary terrestrial habitat and its implications for ecological recovery of Lakeside zones. Knowledge & Management of Aquatic Ecosystems 2014, null, 8, 10.1051/kmae/2013090.

- Thompson, K.; Pederick, W.; Singh, I.; Santhakumar, A.B. Anthocyanin supplementation in alleviating thrombogenesis in overweight and obese population: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, 2017, J. Funct. Foods. 32, 131-138.

- Padmanabhan Monika; Arumugam Geetha; The modulating effect of Persea americana fruit extract on the level of expression of fatty acid synthase complex, lipoprotein lipase, fibroblast growth factor-21 and leptin – A biochemical study in rats subjected to experimental hyperlipidemia and obesity. Phytomedicine 2015, 22, 939-945, 10.1016/j.phymed.2015.07.001.

- Chkhikvishvili, I.; Sanikidze,T.; Gogia, N.; Mchedlishvili, T.; Enukidze, M .; Machavariani,M.; Vinokur,Y.; Rodov, V. Rosmarinic acid-rich extracts of summer savory (Satureja hortensis L.) protect Jurkat T cells against oxidative stress. Oxid. Med. Cell. Long. 2013, 456253, 1-9.

- Pérez-Sánchez, A.; Barrajón-Catalán, E.; Ruiz-Torres, V.; Agulló-Chazarra1, Luz.; Herranz-López, M.; Valdés, A.; Cifuentes, A.; & Micol, V. Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) extract causes ROS-induced necrotic cell death and inhibits tumor growth in vivo. Scientif. Rep. 2019, 9:808.

- Catherine Ulbricht; Tracee Rae Abrams; Ashley Brigham; James Ceurvels; Jessica Clubb; Whitney Curtiss; Catherine DeFranco Kirkwood; Nicole Giese; Kevin Hoehn; Ramon Iovin; Richard Isaac; Erica Rusie; Jill M. Grimes Serrano; Minney Varghese; Wendy Weissner; Regina C. Windsor; An Evidence-Based Systematic Review of Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis) by the Natural Standard Research Collaboration. Journal of Dietary Supplements 2010, 7, 351-413, 10.3109/19390211.2010.525049.

- Eva M. Sánchez-Salcedo; Pedro Mena; Cristina García-Viguera; Juan José Martínez; Francisca Hernández; Phytochemical evaluation of white (Morus alba L.) and black (Morus nigra L.) mulberry fruits, a starting point for the assessment of their beneficial properties. Journal of Functional Foods 2015, 12, 399-408, 10.1016/j.jff.2014.12.010.

- Andrade, J.-M., Faustino, C.; Garcia, C., Ladeiras, D.; Reis, C-P.; Rijo, P. Rosmarinus officinalis L.: an update review of its phytochemistry and biological activity. Future Sci. OA , 2018, 4, FSO283.

- Moore, J.; Yousef, M.; Tsiani E.. Anticancer effects of rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) extract and rosemary extract polyphenols. Nutrients. 2016, 8, 731.

- Ai N. H. Phan; Jong-Whan Choi; Hyungmin Jeong; Anti-cancer effects of polyphenolic compounds in epidermal growth factor receptor tyrosine kinase inhibitor-resistant non-small cell lung cancer. Pharmacognosy Magazine 2017, 13, 595-599, 10.4103/pm.pm_535_16.

- Alice Trivellini; Mariella Lucchesini; Rita Maggini; Haana Mosadegh; Tania Salomè Sulca Villamarin; Paolo Vernieri; Anna Mensuali-Sodi; Alberto Pardossi; Anna Mensuali-Sodi; Lamiaceae phenols as multifaceted compounds: bioactivity, industrial prospects and role of “positive-stress”. Industrial Crops and Products 2016, 83, 241-254, 10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.12.039.

- Sabrina Caxambú; Elaine Biondo; Eliane Maria Kolchinski; Rosiele Lappe Padilha; Adriano Brandelli; Voltaire Sant Anna; Evaluation of the antimicrobial activity of pecan nut [Carya illinoinensis (Wangenh) C. Koch] shell aqueous extract on minimally processed lettuce leaves. Food Science and Technology 2016, 36, 42-45, 10.1590/1678-457x.0043.

- Natasa Simin; Dejan Orčić; Dragana D. Četojević-Simin; Neda Mimica-Dukic; Goran Anačkov; Ivana Beara; Ivan Zaletel; Biljana Bozin; Phenolic profile, antioxidant, anti-inflammatory and cytotoxic activities of small yellow onion (Allium flavum L. subsp. flavum, Alliaceae). LWT 2013, 54, 139-146, 10.1016/j.lwt.2013.05.023.

- Simin, N.; Dragana, M.-C.; Pavic, A.; Orcic, D.; Nemes, I. ; Cetojevic-Simin, D. An overview of the biological activities of less known wild onions (genus Allium sect. Codonoprasum). Biolog. Serbic. 2019, 41(2), 57-62.

- Wen-Chang Chang; Po-Ling Kuo; Chen-Wen Chen; James Swi-Bea Wu; Szu-Chuan Shen; Caffeic acid improves memory impairment and brain glucose metabolism via ameliorating cerebral insulin and leptin signaling pathways in high-fat diet-induced hyperinsulinemic rats. Food Research International 2015, 77, 24-33, 10.1016/j.foodres.2015.04.010.

- Choi, R.; Kim, B.-H, Naowaboot, J. et al. Effects of ferulic acid on diabetic nephropathy in a rat model of type 2 diabetes. Exp. Mol.Med. 2011, 43, 676–683.

- Badawy, D.; El-Bassossy, H.-M.; Fahmy, A.; Azhar, A. Aldose reductase inhibitors zopolrestat and ferulic acid alleviate hypertensionassociated with diabetes: effect on vascular reactivity. Can.J.Physiol.Pharmacol. 2013, 91, 101–107.

- R. Cecily Rosemary Latha; P. Daisy; Insulin-secretagogue, antihyperlipidemic and other protective effects of gallic acid isolated from Terminalia bellerica Roxb. in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Chemico-Biological Interactions 2011, 189, 112-118, 10.1016/j.cbi.2010.11.005.

- Punithavathi, V.-R.; Prince, P.-S.; Kumar, R.; Selvakumari, J. Antihyperglycaemic, antilipidperoxidative and antioxidant effects of gallic acid on streptozotocin induced diabetic. Wistar rats. Eur. J.Pharmacol. 2011, 650, 465–471.

- Ruzena Sotníková; Ľudmila Okruhlicová; Jana Vlkovicova; Jana Navarová; Beata Gajdacova; Lenka Pivackova; Silvia Fialová; Peter Krenek; Rosmarinic acid administration attenuates diabetes-induced vascular dysfunction of the rat aorta. Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmacology 2013, 65, 713-723, 10.1111/jphp.12037.

- G. Jayanthy; S. Subramanian; Rosmarinic acid, a polyphenol, ameliorates hyperglycemia by regulating the key enzymes of carbohydrate metabolism in high fat diet – STZ induced experimental diabetes mellitus. Biomedicine & Preventive Nutrition 2014, 4, 431-437, 10.1016/j.bionut.2014.03.006.