| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ahmad Ilyas Rushdan | + 2644 word(s) | 2644 | 2021-02-03 07:11:49 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 2644 | 2021-02-07 10:58:03 | | |

Video Upload Options

Cellulose is the main substance of a plant’s cell walls, helping plants to remain stiff and upright, hence, it can be extracted from plant sources, agriculture waste, animals, and bacterial pellicle. It is composed of polymer chains consisting of unbranched β (1,4) linked D glucopyranosyl units (anhydroglucose unit, AGU).

1. Introduction

Petroleum-based synthesis polymers are non-degradable materials and they cause pollution to nature [1]. Therefore in order to minimize the effect of these polymers, cellulose is introduced. Cellulose offers excellent properties to minimize this damage by utilization as a filler in the manufacturing of either a synthesis matrix or a natural starch matrix. Cellulose is the main substance of a plant’s cell walls, helping plants to remain stiff and upright, hence, it can be extracted from plant sources, agriculture waste, animals, and bacterial pellicle [2][3]. It is composed of polymer chains consisting of unbranched β (1,4) linked D glucopyranosyl units (anhydroglucose unit, AGU) [4][5]. Cellulose also possesses excellent mechanical properties, such as tensile and flexural strengths, tensile and flexural moduli, and thermal resistance, as well as low cost, due to its availability from different resources and abundance in nature, and degradability which is not obtainable in synthetic fillers, that makes it an excellent bio-filler for both synthesis or natural polymer matrixes [6]. Cellulose needs to be extracted to be a useful substance. Cellulose extraction can be achieved via three approaches; mechanical, chemical, and bacterial techniques. Mechanical cellulose extraction comprises of high-pressurized homogenization [7], grinding [8], crushing [9], and steam explosion methods [10]. Chemical extraction methods include alkali treatment [11], acid retting, chemical retting [12], and degumming [13].

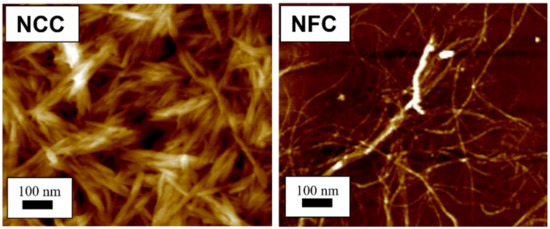

Cellulose can be extracted in different sizes, depending on the intended application. Micro- and nanocellulose are the common sizes of cellulose used in industrial applications. Nanocellulose is divided into three types, (1) nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), also known as nanofibrils or microfibrils or macrofibrillated cellulose or nanofibrillated cellulose; (2) nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC), also known as crystallites, whiskers, or rod-like cellulose microcrystals, and (3) bacterial nanocellulose (BNC), also known as microbial cellulose or biocellulose [14][15]. The difference between microfibrillated cellulose and nanocrystalline cellulose is the fiber size distributions that are wide in microfibrillated cellulose and narrow or drastically shorter in nanocrystalline cellulose [16]. Figure 1 depicts the structural difference between nanofibrillated cellulose and nanocrystalline cellulose. Similar to microfibrillated cellulose, bacterial cellulose also has a narrow size distribution and high crystallinity, except for its source, which is bacteria. According to Alain Dufresne [17] and Chirayil et al. [18], NCC and NFC are renowned not only for their biodegradation, superb properties, unique structures, low density, excellent mechanical performance, high surface area and aspect ratio, biocompatibility, and natural abundance, but also for their possibility to modify their surfaces to enhance their nano-reinforcement compatibility with other polymers due to the presence of abundant hydroxyl groups. Nanocellulose-based materials, also known as a new ageless bionanomaterial, are non-toxic, recyclable, sustainable, and carbon-neutral [17]. NCC and NFC have demonstrated numerous advanced applications, including in the automotive industry, optically transparent materials, drug supply, coating films, tissue technology, biomimetic materials, aerogels, sensors, three-dimensional (3D) printing, rheology modifiers, energy harvesters, filtration, textiles, printed and flexible electronics, composites, paper and board, packaging, oil and gas, medical and healthcare, and scaffolding [19][20]. In addition, macro and mesoporous nanocellulose beads also are utilized in energy storage devices. The cellulose beads act as electrodes that serve as complements to conventional supercapacitors and batteries [21], and depend on the properties of the cellulose (e.g., origin, porosity, pore distribution, pore-size distribution, and crystallinity) [22]. In consequence, the number of patents and publications on nanocellulose over 20 years have increased significantly from 764 in 2000 to 18,418 in 2020. In addition, this increment of more than 2300% over 20 years indicates that nanocellulose has become the advanced emerging material in the 21st century.

Figure 1. Atomic force microscopy images show different structure between nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC) [23] and nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC) [24]. (Reproduced with copyright permission from Ilyas et al. [23][24]).

Applications of cellulose are vast and interfere with many fields concentrated on mechanical, medical, and industrial applications [25]. In industry, cellulose is used as a filler for matrixes in the manufacturing of a degradable polymer. Cellulose is also used in packaging applications, tissue engineering applications, electronic, optical, sensor, pharmaceutical applications, cosmetic applications, insulation, water filtration, hygienic applications, as well as vascular graft applications [26][27][28]. For instance, in Li-ion battery application, cellulose has been applied along with carbon nanotubes (CNT) as current collectors [29]. Previously, the current collector in the battery used the conventional aluminum foil. From this point of view, cellulose paper-CNTs-based electrodes showed ~17% improvement in areal capacity compared to commercial aluminum-based electrodes. Another renowned application of cellulose is the implementation of electrospun cellulose acetate nanofibers for antimicrobial activity as mentioned by Kalwar and Shen [30]. Moreover, cellulose is highly efficient in antitumor drug delivery [31]. In this case, the application of carboxymethyl cellulose-grafted graphene oxide drug delivery system has a huge potential in colon cancer therapy. The cellulose can also be implemented in the oil and gas industry due to its large surface areas and high volume concentrations along with unique mechanical, chemical, thermal, and magnetic properties [32]. Cellulose can also be used as additive and reinforcement for cross arm application in transmission towers in order to improve their mechanical properties and electrical resistance performance [33][34]. To increase the base of potential applications, cellulose’s properties need to be more flexible in terms of modification and improvement to match the required properties of various applications [35].

2. Classification of Cellulose

Cellulose can be classified into two types based on size, microcellulose and nanocellulose, while nanocellulose can be classified in three types: (1) nano- or microfibrillated cellulose (NFC)/(MFC), (2) nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC), and (3) bacterial nanocellulose (BNC) [36][37]. The advantage of extracting or isolating cellulose is that the nanocellulose can be obtained from microcellulose [6][38], producing different cellulose sizes in a compatible procedure.

Nanocellulose can be categorized into the family in nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC), nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC), and bacterial nanocellulose (BNC). The size of nanocellulose ranges from 5 nm to 100 nm [39]. The difference between nanofibrillated cellulose (NFC) and microfibrillated cellulose (MFC) is that NFC is usually produced using a chemical pretreatment followed by a high-pressurized homogenization, while MFC is commonly yielded from chemical treatment [40]. The sources of NFC or MFC are wood, sugar beet, potato tuber, hemp, and flax. The average diameter is 20–50 nm [41][42]. Meanwhile, for nanocrystalline cellulose (NCC), the average range of NCC diameter and length are 5–70 nm and 100 nm, respectively [43]. NCC can be extracted from several sources like plants (wood, cotton, hemp, flax, wheat straw, mulberry bark, ramie, avicel, and tunicin), algae and bacteria, and animals (tunicates) [44]. Another type of nanocellulose that can be produced from non-plant sources is bacterial nanocellulose (BNC). Using microorganisms in the industry of biopolymers is vital because such microorganisms exhibit rapid growth, allowing for high yields and year-round availability of the product [45]. There are two main methods for producing BNC using microorganisms: static culture and stirred culture [46]. Static culture employs the accumulation of a thick, leather-like white BNC pellicle at the air-liquid interface. The stirred culture synthesizes cellulose in a dispersed manner in the culture medium, forming irregular pellets or suspended fibers [47].

It is better to produce bacterial cellulose by static culture because previous studies have shown that bacterial cellulose produced from a static culture has higher mechanical strength and yields than those obtained from stirred culture. Moreover, stirred culture has a higher probability of microorganism mutations, which might affect BNC production. The disadvantage of a static culture is that it takes more time and a larger area of cultivation [48][49][50][51].

3. Microcellulose and Nanocellulose Extraction, Treatment, and Modification

Lately, natural fiber biopolymers have been significantly used as alternatives to synthetic polymer which negatively affected the environment [52]. Green composites can be enrolled in many applications, such as automobiles, packaging, construction, building materials, furniture industry, etc. [53][54][55][56][57][58]. Cellulose is the main component of several natural fibers, such as sugarcane bagasse, cotton, cogon grass, flax, hemp, jute, and sisal [59][60][61][62][63][64], and it can also be found in sea animals, bacteria, and fungi. Cellulose can be extracted in microscale with an excessive amount of mineral acids, the crystalline phases at nanometer range [65], with sizes of 10–200 μm [66], and the mean diameter of approximately 44.28 μm [67]. The structure of microcellulose can be divided into microfibrillated cellulose or microcrystalline cellulose; microcrystalline cellulose has higher strength than the microfibrillated cellulose [4]. Cellulose can also be extracted as nanocellulose size of nanocellulose fiber, which generally contains less than 100 nm in diameter and several micrometers in length [68]. Plant natural fiber consists of cellulose and non-cellulose materials such as lignin, hemicellulose, pectin, wax, and other extractives. Therefore, in order to extract cellulose either as micro or nano, the non-cellulose materials must be removed. There are two common methods to remove non-cellulosic materials that were used by researchers, (I) acid chlorite treatment and (II) alkaline treatment [69][70]. Depending on the conditions of extraction process and extraction technique, the crystalline region of the cellulose can significantly vary in size and aspect ratio. This usually results in the types of fibrils, crystalline, and particle sizes (micro- or nano-size). However, they are normally anisometric.

3.1. Cellulose Extraction Techniques

There are several types of cellulose production techniques such as mechanical treatment, chemical treatment, combination of chemi-mechanical process, as well as bacterial production of cellulose.

3.1.1. Mechanical Extraction

High-pressurized homogenization is one of the mechanical extraction techniques. High-pressurized homogenization is used for large-scale nanocellulose production by forcing the material through a very narrow channel or orifice using a piston under high pressure of 50–2000 MPa [66]. This is an environmentally friendly method for nanocellulose isolation [71]. However, there is a possibility for the occurrence of mechanical damage to the crystalline structure using this method [72]. Another mechanical technique is grinding. Grinding is used to separate nanocellulose from fiber by applying shear stress on the fiber by rotating grindstones at approximately 1500 rpm [73]. The heat produced by friction during the fibrillation process leads to water evaporation, which improves the extraction process [74]. In addition, crushing is also used to extract cellulose fiber. This method is used to produce microcellulose in frozen places [75]. The size of the produced cellulose ranges between 0.1 and 1 μm. This process can be used as a pretreatment prior to high-pressurized homogenization to yield nanocellulose. Steam explosion is utilized for the extraction of cellulose, which uses a low energy consumption method to extract the cellulose. Although it does not completely remove lignin, it can be considered a pretreatment. After applying this method, the obtained fiber needs mechanical modification.

3.1.2. Chemical Extraction

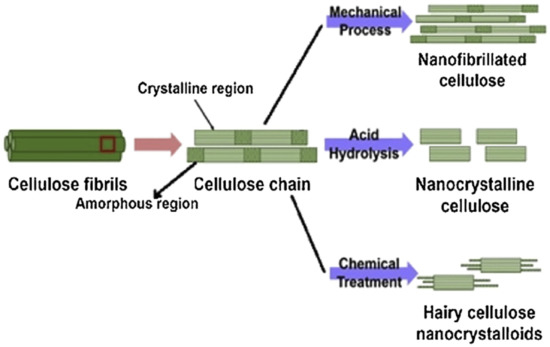

Chemical extraction procedures extract cellulose by using alkali retting, acid retting, chemical retting, chemical assisted natural (CAN), or degumming to remove the lignin content in the fibers. These treatments also affect other components of the fiber microstructure, including pectin, hemicellulose, and other non-cellulosic materials [76][77][78][79]. One of the examples using the chemical extraction method is alkali or acid retting. This extraction method causes less fiber damage [80], while mechanical extraction is less costly. It is performed by heating, cleaning, and soaking the fiber in alkali or acid solution [81]. This method has the ability to improve some properties of the fiber. Degumming, which is one of the chemical extraction processes that is developed to hold the ramie fiber’s shape, works by eliminating the gummy and pectin content [82]. Another chemical technique is chemical retting. This procedure is used to reduce the lignin and water content in fibers. Chemical retting is able to remove more lignin compared to alkali and acid retting but is less effective in terms of eliminating moisture [12]. A combination of the chemical and mechanical extraction methods can be applied to guarantee higher efficiency of lignin removal, where the mechanical processes usually are done after chemical treatment [83]. Figure 2 shows the extraction of nanocellulose from lignocellulosic biomass via mechanical and chemical methods.

Figure 2. Extraction of nanocellulose from lignocellulosic biomass (reproduced with copyright permission from Sharma et al. [84]).

3.1.3. Bacterial Production of Cellulose

Bacterial cellulose is of similar molecular formula to plant origin cellulose, characterized by a crystalline nanofibrillar structure which creates a large surface area that can retain a large amount of liquid. There are many methods for bacterial cellulose preparation, including static, agitated/shaking, and bioreactor cultures. The results of macroscopic morphology, microstructure, mechanical properties of bacterial cellulose are different, depending on the preparation method. The static culture method enhances the accumulation of a gelatinous membrane of cellulose at the surface of the nutrition solution, whereas the agitated/shaking culture affects the asterisk-like, sphere-like, pellet-like, or irregular masses [36]. The required properties and the applications dictate the selection of the appropriate preparation method. Producing cellulose-based bacterial resources gives higher critical surface tension and higher thermal degradation temperature while the cellulose extracted from plants via combination of the chemical and mechanical extraction methods has a hierarchical organization and semi-crystalline nature.

3.2. Cellulose Surface Treatment and Modification

Cellulose is the most abundant component that can be found almost exclusively in plant cell walls; it can also be produced by some algae and bacteria [85]. The applications of natural biopolymers have extended in last recent years due to the improvement in the processes of surface treatment and modifications; these applications involve automobiles, construction, building materials like nano building blocks in composites, furniture industry, and optical applications [53][86]. The cellulose fiber has two main drawbacks, (1) high number of hydroxyl groups that makes the product’s structure gel-like and (2) high hydrophilicity [87], which limit its uses in several applications. The purpose of the modification is to improve these two drawbacks to enhance the cellulose’s properties and broaden the applications of natural fiber [88].

To reduce energy consumption during cellulose manufacturing and to extract cellulose in an effective way, pretreatment needs to be carried out. The pretreatment can be either enzymatic pretreatment or TEMPO (2,2,6,6-tetramethylpiperidine-1-oxyl) pretreatment. Enzymatic pretreatment can be divided into cellobiohydrolases and endoglucanases [89][90], which show strong synergistic effects [91]. TEMPO-mediated oxidation pretreatment is a treatment that must be performed in solution. TEMPO-mediated oxidation pretreatment improves the reactivity of cellulose, and the C6 primary hydroxyl groups of cellulose are converted to carboxylate groups via the C6 aldehyde groups [92][93]. The main cellulose modifications are presented in the following subsections.

3.2.1. Molecule Chemical Grafting

The reaction mechanism in this technique is to improve the structure and properties of cellulose, and only happens on the cellulose chains located on the surface of the cellulose. The limitation on the extent of acetylation (ester bonds are formed between cellulose and cyclodextrins) lies in the susceptibility and ease to maintain the surface; however, this technique does not make the cellulose fully dissolved because of the complex network formation [94].

3.2.2. Surface Adsorption on Cellulose

The adsorption on the surface of cellulose is usually done by using surfactants. There are many types of surfactants, such as fluorosurfactant, e.g., perfluorooctadecanoic acid used to coat cellulose [95], cationic surfactant [96][97], and polyelectrolyte solution [9][98]. Surfactants improve hydrophobic behavior; however, they might also change the physical properties and produce some cracks that possibly make absorption of water and moisture occur.

3.2.3. Direct Chemical Modification Methods

The properties of cellulose, such as its hydrophilic or hydrophobic character, elasticity, water sorbency, adsorptive or ion exchange capability, resistance to microbiological attack, and thermal resistance are usually modified by chemical treatments. The main methods of cellulose chemical modification are esterification, etherification, halogenations, oxidation, and alkali treatment [99]. The chemical modifications methods of cellulose are the best methods to achieve adequate structural durability and an efficient adsorption capacity.

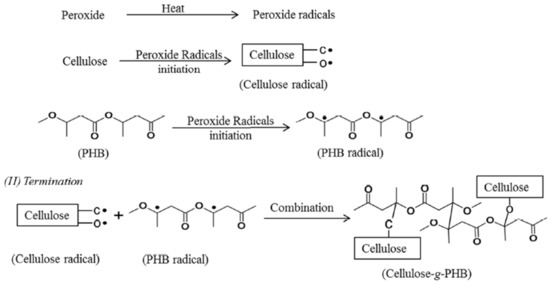

3.2.4. Cellulose Grafting

Grafting on cellulose by attaching or adding the particles of molecules covalently to the cellulose can be done by either using coupling agents or activating the cellulose substrates [88]. Vinyl monomers grafting on cellulose can be performed in homogeneous or heterogeneous medium [100]. When polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) is grafted with cellulose, it improves the properties of the cellulose in terms of crystallinity, flexibility, and the chemically linking of the fibers with the matrix [101]. Figure 3 illustrates the general mechanism of peroxide radical initiated grafting of PHB onto cellulose. Polyethylene glycol (PEG) and aminosilane are also used as grafting materials [102][103], where these materials increase the cellulose polarity to have better compatibility with the polymer.

Figure 3. The general mechanism of peroxide radical initiated grafting of polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) onto cellulose (reproduced with copyright permission from Wei et al. [101]).

References

- Sapuan, S.M.; Aulia, H.S.; Ilyas, R.A.; Atiqah, A.; Dele-Afolabi, T.T.; Nurazzi, M.N.; Supian, A.B.M.; Atikah, M.S.N. Mechanical properties of longitudinal basalt/woven-glass-fiber-reinforced unsaturated polyester-resin hybrid composites. Polymers 2020, 12, 2211, doi:10.3390/polym12102211.

- Asyraf, M.R.M.; Ishak, M.R.; Sapuan, S.M.; Yidris, N.; Ilyas, R.A. Woods and composites cantilever beam: A comprehensive review of experimental and numerical creep methodologies. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 6759–6776, doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2020.01.013.

- Ilyas, R.A.; Sapuan, S.M.; Atiqah, A.; Ibrahim, R.; Abral, H.; Ishak, M.R.; Zainudin, E.S.; Nurazzi, N.M.; Atikah, M.S.N.; Ansari, M.N.M.; et al. Sugar palm (Arenga pinnata [Wurmb.] Merr) starch films containing sugar palm nanofibrillated cellulose as reinforcement: Water barrier properties. Polym. Compos. 2020, 41, 459–467, doi:10.1002/pc.25379.

- Abdul Khalil, H.P.S.; Bhat, A.H.; Yusra, A.F.I. Green composites from sustainable cellulose nanofibrils: A review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 87, 963–979, doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2011.08.078.

- Syafiq, R.; Sapuan, S.M.; Zuhri, M.Y.M.; Ilyas, R.A.; Nazrin, A.; Sherwani, S.F.K.; Khalina, A. Antimicrobial activities of starch-based biopolymers and biocomposites incorporated with plant essential oils: A review. Polymers 2020, 12, 2403, doi:10.3390/polym12102403.

- Shankar, S.; Rhim, J.W. Preparation of nanocellulose from micro-crystalline cellulose: The effect on the performance and properties of agar-based composite films. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 135, 18–26, doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.08.082.

- Tian, C.; Yi, J.; Wu, Y.; Wu, Q.; Qing, Y.; Wang, L. Preparation of highly charged cellulose nanofibrils using high-pressure homogenization coupled with strong acid hydrolysis pretreatments. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 136, 485–492, doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.09.055.

- Nair, S.S.; Zhu, J.Y.; Deng, Y.; Ragauskas, A.J. Characterization of cellulose nanofibrillation by micro grinding. J. Nanopart. Res. 2014, 16, 2349, doi:10.1007/s11051-014-2349-7.

- Mocchiutti, P.; Schnell, C.N.; Rossi, G.D.; Peresin, M.S.; Zanuttini, M.A.; Galván, M.V. Cationic and anionic polyelectrolyte complexes of xylan and chitosan. Interaction with lignocellulosic surfaces. Carbohydr. Polym. 2016, 150, 89–98, doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2016.04.111.

- Zeng, J.; Tong, Z.; Wang, L.; Zhu, J.Y.; Ingram, L. Isolation and structural characterization of sugarcane bagasse lignin after dilute phosphoric acid plus steam explosion pretreatment and its effect on cellulose hydrolysis. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 154, 274–281, doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2013.12.072.

- Wang, W.; Liang, T.; Bai, H.; Dong, W.; Liu, X. All cellulose composites based on cellulose diacetate and nanofibrillated cellulose prepared by alkali treatment. Carbohydr. Polym. 2018, 179, 297–304, doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.09.098.

- Kaur, V.; Chattopadhyay, D.P.; Kaur, S. Study on Extraction of Bamboo Fibres from Raw Bamboo Fibres Bundles Using Different Retting Techniques. Text. Light Ind. Sci. Technol. 2013, 2, 174–179.

- Li, Z.; Meng, C.; Yu, C. Analysis of oxidized cellulose introduced into ramie fiber by oxidation degumming. Text. Res. J. 2015, 85, 2125–2135, doi:10.1177/0040517515581589.

- Abitbol, T.; Rivkin, A.; Cao, Y.; Nevo, Y.; Abraham, E.; Ben-Shalom, T.; Lapidot, S.; Shoseyov, O. Nanocellulose, a tiny fiber with huge applications. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2016, 39, 76–88, doi:10.1016/j.copbio.2016.01.002.

- Klemm, D.; Cranston, E.D.; Fischer, D.; Gama, M.; Kedzior, S.A.; Kralisch, D.; Kramer, F.; Kondo, T.; Lindström, T.; Nietzsche, S.; et al. Nanocellulose as a natural source for groundbreaking applications in materials science: Today’s state. Mater. Today 2018, 21, 720–748, doi:10.1016/j.mattod.2018.02.001.

- Thompson, L.; Azadmanjiri, J.; Nikzad, M.; Sbarski, I.; Wang, J.; Yu, A. Cellulose nanocrystals: Production, functionalization and advanced applications. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2019, 58, 1–16, doi:10.1515/rams-2019-0001.

- Dufresne, A. Nanocellulose: A new ageless bionanomaterial. Mater. Today 2013, 16, 220–227, doi:10.1016/j.mattod.2013.06.004.

- Chirayil, C.J.; Mathew, L.; Thomas, S. Review of recent research in nano cellulose preparation from different lignocellulosic fibers. Rev. Adv. Mater. Sci. 2014, 37, 20–28.

- Ferreira, F.V.; Otoni, C.G.; De France, K.J.; Barud, H.S.; Lona, L.M.F.; Cranston, E.D.; Rojas, O.J. Porous nanocellulose gels and foams: Breakthrough status in the development of scaffolds for tissue engineering. Mater. Today 2020, 37, 126–141, doi:10.1016/j.mattod.2020.03.003.

- Ansari, F.; Ding, Y.; Berglund, L.A.; Dauskardt, R.H. Toward Sustainable Multifunctional Coatings Containing Nanocellulose in a Hybrid Glass Matrix. ACS Nano 2018, 12, 5495–5503, doi:10.1021/acsnano.8b01057.

- Erlandsson, J.; López Durán, V.; Granberg, H.; Sandberg, M.; Larsson, P.A.; Wågberg, L. Macro- and mesoporous nanocellulose beads for use in energy storage devices. Appl. Mater. Today 2016, 5, 246–254, doi:10.1016/j.apmt.2016.09.008.

- Wang, Z.; Lee, Y.H.; Kim, S.W.; Seo, J.Y.; Lee, S.Y.; Nyholm, L. Why Cellulose-Based Electrochemical Energy Storage Devices? Adv. Mater. 2020, 2000892, 1–18, doi:10.1002/adma.202000892.

- Ilyas, R.A.; Sapuan, S.M.; Atikah, M.S.N.; Asyraf, M.R.M.; Rafiqah, S.A.; Aisyah, H.A.; Nurazzi, N.M.; Norrrahim, M.N.F. Effect of hydrolysis time on the morphological, physical, chemical, and thermal behavior of sugar palm nanocrystalline cellulose (Arenga pinnata (Wurmb.) Merr). Text. Res. J. 2021, 1-2, 152–167, doi:10.1177/0040517520932393.

- Ilyas, R.A.; Sapuan, S.M.; Ishak, M.R.; Zainudin, E.S. Sugar palm nanofibrillated cellulose (Arenga pinnata (Wurmb.) Merr): Effect of cycles on their yield, physic-chemical, morphological and thermal behavior. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 123, 379–388, doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2018.11.124.

- Azammi, A.M.N.; Ilyas, R.A.; Sapuan, S.M.; Ibrahim, R.; Atikah, M.S.N.; Asrofi, M.; Atiqah, A. Characterization studies of biopolymeric matrix and cellulose fibres based composites related to functionalized fibre-matrix interface. In Interfaces in Particle and Fibre Reinforced Composites; Elsevier: London, UK, 2020; pp. 29–93, ISBN 9780081026656.

- Abral, H.; Basri, A.; Muhammad, F.; Fernando, Y.; Hafizulhaq, F.; Mahardika, M.; Sugiarti, E.; Sapuan, S.M.; Ilyas, R.A.; Stephane, I. A simple method for improving the properties of the sago starch films prepared by using ultrasonication treatment. Food Hydrocoll. 2019, 93, 276–283, doi:10.1016/j.foodhyd.2019.02.012.

- Abral, H.; Atmajaya, A.; Mahardika, M.; Hafizulhaq, F.; Kadriadi; Handayani, D.; Sapuan, S.M.; Ilyas, R.A. Effect of ultrasonication duration of polyvinyl alcohol (PVA) gel on characterizations of PVA film. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 2477–2486, doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2019.12.078.

- Shatkin, J.A.; Wegner, T.H.; Bilek, E.M.; Cowie, J. Market projections of cellulose nanomaterial-enabled products—Part 1: Applications. TAPPI J. 2014, 13, 9–16, doi:10.32964/tj13.5.9.

- Ventrapragada, L.K.; Creager, S.E.; Rao, A.M.; Podila, R. Carbon Nanotubes Coated Paper as Current Collectors for Secondary Li-ion Batteries. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2019, 8, 18–23, doi:10.1515/ntrev-2019-0002.

- Kalwar, K.; Shen, M. Electrospun cellulose acetate nanofibers and Au@AgNPs for antimicrobial activity—A mini review. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2019, 8, 246–257, doi:10.1515/ntrev-2019-0023.

- Jiao, Z.; Zhang, B.; Li, C.; Kuang, W.; Zhang, J.; Xiong, Y.; Tan, S.; Cai, X.; Huang, L. Carboxymethyl cellulose-grafted graphene oxide for efficient antitumor drug delivery. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2018, 7, 291–301, doi:10.1515/ntrev-2018-0029.

- Zhe, Z.; Yuxiu, A. Nanotechnology for the oil and gas industry- A n overview of recent progress. Nanotechnol. Rev. 2018, 7, 341–353, doi:10.1515/ntrev-2018-0061.

- Asyraf, M.R.M.; Ishak, M.R.; Sapuan, S.M.; Yidris, N.; Ilyas, R.A.; Rafidah, M.; Razman, M.R. Potential Application of Green Composites for Cross Arm Component in Transmission Tower: A Brief Review. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2020, 2020, 8878300, doi:10.1155/2020/8878300.

- Johari, A.N.; Ishak, M.R.; Leman, Z.; Yusoff, M.Z.M.; Asyraf, M.R.M. Influence of CaCO3 in pultruded glass fibre/unsaturated polyester composite on flexural creep behaviour using conventional and TTSP methods. Polimery 2020, 65, 46–54, doi:dx.doi.org/10.14314/polimery.2020.11.6.

- Asyraf, M.R.M.; Rafidah, M.; Ishak, M.R.; Sapuan, S.M.; Ilyas, R.A.; Razman, M.R. Integration of TRIZ, Morphological Chart and ANP method for development of FRP composite portable fire extinguisher. Polym. Compos. 2020, 41, 2917–2932, doi:10.1002/pc.25587.

- Klemm, D.; Kramer, F.; Moritz, S.; Lindström, T.; Ankerfors, M.; Gray, D.; Dorris, A. Nanocelluloses: A new family of nature-based materials. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011, 50, 5438–5466, doi:10.1002/anie.201001273.

- Ferrer, A.; Pal, L.; Hubbe, M. Nanocellulose in packaging: Advances in barrier layer technologies. Ind. Crops Prod. 2017, 95, 574–582, doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.11.012.

- Ilyas, R.A.; Sapuan, S.M.; Norrrahim, M.N.F.; Yasim-Anuar, T.A.T.; Kadier, A.; Kalil, M.S.; Atikah, M.S.N.; Ibrahim, R.; Asrofi, M.; Abral, H.; et al. Nanocellulose/starch biopolymer nanocomposites: Processing, manufacturing, and applications. In Advanced Processing, Properties, and Application of Strach and Other Bio-Based Polymer; Al-Oqla, F.M., Ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021.

- Islam, M.T.; Alam, M.M.; Patrucco, A.; Montarsolo, A.; Zoccola, M. Preparation of nanocellulose: A review. AATCC J. Res. 2014, 1, 17–23, doi:10.14504/ajr.1.5.3.

- Kumar, V.; Bollström, R.; Yang, A.; Chen, Q.; Chen, G.; Salminen, P.; Bousfield, D.; Toivakka, M. Comparison of nano- and microfibrillated cellulose films. Cellulose 2014, 21, 3443–3456, doi:10.1007/s10570-014-0357-5.

- Siqueira, G.; Bras, J.; Dufresne, A. Cellulosic Bionanocomposites: A Review of Preparation, Properties and Applications. Polymers 2010, 2, 728–765, doi:10.3390/polym2040728.

- Lavoine, N.; Desloges, I.; Sillard, C.; Bras, J. Controlled release and long-term antibacterial activity of chlorhexidine digluconate through the nanoporous network of microfibrillated cellulose. Cellulose 2014, 21, 4429–4442, doi:10.1007/s10570-014-0392-2.

- Moon, R.J.; Martini, A.; Nairn, J.; Simonsen, J.; Youngblood, J. Cellulose nanomaterials review: Structure, properties and nanocomposites. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2011, 40, 3941, doi:10.1039/c0cs00108b.

- Brinchi, L.; Cotana, F.; Fortunati, E.; Kenny, J.M. Production of nanocrystalline cellulose from lignocellulosic biomass: Technology and applications. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 94, 154–169, doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.01.033.

- Santos-Ebinuma, V.C.; Roberto, I.C.; Simas Teixeira, M.F.; Pessoa, A. Improving of red colorants production by a new Penicillium purpurogenum strain in submerged culture and the effect of different parameters in their stability. Biotechnol. Prog. 2013, 29, 778–785, doi:10.1002/btpr.1720.

- Jozala, A.F.; de Lencastre-Novaes, L.C.; Lopes, A.M.; de Carvalho Santos-Ebinuma, V.; Mazzola, P.G.; Pessoa, A., Jr.; Grotto, D.; Gerenutti, M.; Chaud, M.V. Bacterial nanocellulose production and application: A 10-year overview. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 100, 2063–2072, doi:10.1007/s00253-015-7243-4.

- Krystynowicz, A.; Czaja, W.; Wiktorowska-Jezierska, A.; Gonçalves-Miśkiewicz, M.; Turkiewicz, M.; Bielecki, S. Factors affecting the yield and properties of bacterial cellulose. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2002, 29, 189–195, doi:10.1038/sj.jim.7000303.

- Chawla, P.R.; Bajaj, I.B.; Survase, S.A.; Singhal, R.S. Microbial cellulose: Fermentative production and applications. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2009, 47, 107–124.

- Lee, K.Y.; Buldum, G.; Mantalaris, A.; Bismarck, A. More than meets the eye in bacterial cellulose: Biosynthesis, bioprocessing, and applications in advanced fiber composites. Macromol. Biosci. 2014, 14, 10–32, doi:10.1002/mabi.201300298.

- Jeon, S.; Yoo, Y.M.; Park, J.W.; Kim, H.J.; Hyun, J. Electrical conductivity and optical transparency of bacterial cellulose based composite by static and agitated methods. Curr. Appl. Phys. 2014, 14, 1621–1624, doi:10.1016/j.cap.2014.07.010.

- Tyagi, N.; Suresh, S. Production of cellulose from sugarcane molasses using Gluconacetobacter intermedius SNT-1: Optimization & characterization. J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 71–80, doi:10.1016/j.jclepro.2015.07.054.

- Huang, X.; Netravali, A. Biodegradable green composites made using bamboo micro/nano-fibrils and chemically modified soy protein resin. Compos. Sci. Technol. 2009, 69, 1009–1015, doi:10.1016/j.compscitech.2009.01.014.

- Mohammed, L.; Ansari, M.N.M.; Pua, G.; Jawaid, M.; Islam, M.S. A Review on Natural Fiber Reinforced Polymer Composite and Its Applications. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2015, 2015, 243947, doi:10.1155/2015/243947.

- Nurazzi, N.M.; Khalina, A.; Sapuan, S.M.; Ilyas, R.A. Mechanical properties of sugar palm yarn/woven glass fiber reinforced unsaturated polyester composites : Effect of fiber loadings and alkaline treatment. Polimery 2019, 64, 12–22, doi:10.14314/polimery.2019.10.3.

- Mazani, N.; Sapuan, S.M.; Sanyang, M.L.; Atiqah, A.; Ilyas, R.A. Design and fabrication of a shoe shelf from kenaf fiber reinforced unsaturated polyester composites. In Lignocellulose for Future Bioeconomy; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 315–332, ISBN 9780128163542.

- Nurazzi, N.M.; Khalina, A.; Sapuan, S.M.; Ilyas, R.A.; Rafiqah, S.A.; Hanafee, Z.M. Thermal properties of treated sugar palm yarn/glass fiber reinforced unsaturated polyester hybrid composites. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2020, 9, 1606–1618, doi:10.1016/j.jmrt.2019.11.086.

- Norizan, M.N.; Abdan, K.; Ilyas, R.A.; Biofibers, S.P. Effect of fiber orientation and fiber loading on the mechanical and thermal properties of sugar palm yarn fiber reinforced unsaturated polyester resin composites. Polimery 2020, 65, 34–43, doi:10.14314/polimery.2020.2.5.

- Ayu, R.S.; Khalina, A.; Harmaen, A.S.; Zaman, K.; Isma, T.; Liu, Q.; Ilyas, R.A.; Lee, C.H. Characterization Study of Empty Fruit Bunch (EFB) Fibers Reinforcement in Poly(Butylene) Succinate (PBS)/Starch/Glycerol Composite Sheet. Polymers 2020, 12, 1571, doi:10.3390/polym12071571.

- Morán, J.I.; Alvarez, V.A.; Cyras, V.P.; Vázquez, A. Extraction of cellulose and preparation of nanocellulose from sisal fibers. Cellulose 2008, 15, 149–159, doi:10.1007/s10570-007-9145-9.

- Jumaidin, R.; Khiruddin, M.A.A.; Asyul Sutan Saidi, Z.; Salit, M.S.; Ilyas, R.A. Effect of cogon grass fibre on the thermal, mechanical and biodegradation properties of thermoplastic cassava starch biocomposite. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 146, 746–755, doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2019.11.011.

- Sari, N.H.; Pruncu, C.I.; Sapuan, S.M.; Ilyas, R.A.; Catur, A.D.; Suteja, S.; Sutaryono, Y.A.; Pullen, G. The effect of water immersion and fibre content on properties of corn husk fibres reinforced thermoset polyester composite. Polym. Test. 2020, 91, 106751, doi:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2020.106751.

- Jumaidin, R.; Saidi, Z.A.S.; Ilyas, R.A.; Ahmad, M.N.; Wahid, M.K.; Yaakob, M.Y.; Maidin, N.A.; Rahman, M.H.A.; Osman, M.H. Characteristics of Cogon Grass Fibre Reinforced Thermoplastic Cassava Starch Biocomposite: Water Absorption and Physical Properties. J. Adv. Res. Fluid Mech. Therm. Sci. 2019, 62, 43–52.

- Aisyah, H.A.; Paridah, M.T.; Sapuan, S.M.; Khalina, A.; Berkalp, O.B.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, C.H.; Nurazzi, N.M.; Ramli, N.; Wahab, M.S.; et al. Thermal Properties of Woven Kenaf/Carbon Fibre-Reinforced Epoxy Hybrid Composite Panels. Int. J. Polym. Sci. 2019, 2019, 5258621, doi:10.1155/2019/5258621.

- Jumaidin, R.; Ilyas, R.A.; Saiful, M.; Hussin, F.; Mastura, M.T. Water Transport and Physical Properties of Sugarcane Bagasse Fibre Reinforced Thermoplastic Potato Starch Biocomposite. J. Adv. Res. Fluid Mech. Therm. Sci. 2019, 61, 273–281.

- Trache, D.; Hussin, M.H.; Hui Chuin, C.T.; Sabar, S.; Fazita, M.R.N.; Taiwo, O.F.A.; Hassan, T.M.; Haafiz, M.K.M. Microcrystalline cellulose: Isolation, characterization and bio-composites application—A review. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 93, 789–804.

- Kargarzadeh, H.; Ioelovich, M.; Ahmad, I.; Thomas, S.; Dufresne, A. Methods for Extraction of Nanocellulose from Various Sources. Handb. Nanocellulose Cellul. Nanocomposites 2017, 1–51, doi:10.1002/9783527689972.ch1.

- Kian, L.K.; Jawaid, M.; Ariffin, H.; Alothman, O.Y. Isolation and characterization of microcrystalline cellulose from roselle fibers. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 103, 931–940, doi:10.1016/j.ijbiomac.2017.05.135.

- Phanthong, P.; Reubroycharoen, P.; Hao, X.; Xu, G.; Abudula, A. Nanocellulose: Extraction and application. Carbon Resour. Convers. 2018, 1, 32–43, doi:10.1016/j.crcon.2018.05.004.

- Haafiz, M.K.M.; Hassan, A.; Zakaria, Z.; Inuwa, I.M. Isolation and characterization of cellulose nanowhiskers from oil palm biomass microcrystalline cellulose. Carbohydr. Polym. 2014, 103, 119–125, doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2013.11.055.

- Sabaruddin, F.A.; Tahir, P.M.; Sapuan, S.M.; Ilyas, R.A.; Lee, S.H.; Abdan, K.; Mazlan, N.; Roseley, A.S.M.; Abdul Khalil, H.P.S. The Effects of Unbleached and Bleached Nanocellulose on the Thermal and Flammability of Polypropylene-Reinforced Kenaf Core Hybrid Polymer Bionanocomposites. Polymers 2021, 13, 116, doi:10.3390/polym13010116.

- Saelee, K.; Yingkamhaeng, N.; Nimchua, T.; Sukyai, P. An environmentally friendly xylanase-assisted pretreatment for cellulose nanofibrils isolation from sugarcane bagasse by high-pressure homogenization. Ind. Crops Prod. 2016, 82, 149–160, doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2015.11.064.

- Rebouillat, S.; Pla, F. State of the Art Manufacturing and Engineering of Nanocellulose: A Review of Available Data and Industrial Applications. J. Biomater. Nanobiotechnol. 2013, 04, 165–188, doi:10.4236/jbnb.2013.42022.

- Siró, I.; Plackett, D. Microfibrillated cellulose and new nanocomposite materials: A review. Cellulose 2010, 17, 459–494, doi:10.1007/s10570-010-9405-y.

- Jonoobi, M.; Harun, J.; Tahir, P.M.; Zaini, L.H.; SaifulAzry, S.; Makinejad, M.D. Characteristics of nanofibers extracted from kenaf core. BioResources 2010, 5, 2556–2566, doi:10.15376/biores.5.4.2556-2566.

- Alemdar, A.; Sain, M. Isolation and characterization of nanofibers from agricultural residues—Wheat straw and soy hulls. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 1664–1671, doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2007.04.029.

- Deshpande, A.P.; Bhaskar Rao, M.; Lakshmana Rao, C. Extraction of bamboo fibers and their use as reinforcement in polymeric composites. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2000, 76, 83–92, doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-4628(20000404)76:1<83::AID-APP11>3.0.CO;2-L.

- Kushwaha, P.K.; Kumar, R. The studies on performance of epoxy and polyester-based composites reinforced with bamboo and glass fibers. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2010, 29, 1952–1962, doi:10.1177/0731684409342006.

- Kushwaha, P.K.; Kumar, R. Studies on performance of acrylonitrile-pretreated bamboo-reinforced thermosetting resin composites. J. Reinf. Plast. Compos. 2010, 29, 1347–1352, doi:10.1177/0731684409103701.

- Abral, H.; Ariksa, J.; Mahardika, M.; Handayani, D.; Aminah, I.; Sandrawati, N.; Sapuan, S.M.; Ilyas, R.A. Highly transparent and antimicrobial PVA based bionanocomposites reinforced by ginger nanofiber. Polym. Test. 2019, 81, 106186, doi:10.1016/j.polymertesting.2019.106186.

- Hyojin, K.; Kazuya, O.; Toru, F.; Kenichi, T. Influence of fiber extraction and surface modification on mechanical properties of green composites with bamboo fiber. J. Adhes. Sci. Technol. 2013, 27, 1348–1358.

- Zakikhani, P.; Zahari, R.; Sultan, M.T.H.; Majid, D.L. Extraction and preparation of bamboo fibre-reinforced composites. Mater. Des. 2014, 63, 820–828, doi:10.1016/j.matdes.2014.06.058.

- Rao, K.M.M.; Rao, K.M. Extraction and tensile properties of natural fibers: Vakka, date and bamboo. Compos. Struct. 2007, 77, 288–295, doi:10.1016/j.compstruct.2005.07.023.

- Phong, N.T.; Fujii, T.; Chuong, B.; Okubo, K. Study on How to Effectively Extract Bamboo Fibers from Raw Bamboo and Wastewater Treatment. J. Mater. Sci. Res. 2011, 1, 144–155, doi:10.5539/jmsr.v1n1p144.

- Sharma, A.; Thakur, M.; Bhattacharya, M.; Mandal, T.; Goswami, S. Commercial application of cellulose nano-composites—A review. Biotechnol. Rep. 2019, 21, e00316, doi:10.1016/j.btre.2019.e00316.

- Kalia, S.; Boufi, S.; Celli, A.; Kango, S. Nanofibrillated cellulose: Surface modification and potential applications. Colloid Polym. Sci. 2014, 292, 5–31, doi:10.1007/s00396-013-3112-9.

- Ling, S.; Chen, W.; Fan, Y.; Zheng, K.; Jin, K.; Yu, H.; Buehler, M.J.; Kaplan, D.L. Biopolymer nanofibrils: Structure, modeling, preparation, and applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2018, 85, 1–56, doi:10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2018.06.004.

- Nishiyama, Y. Structure and properties of the cellulose microfibril. J. Wood Sci. 2009, 55, 241–249, doi:10.1007/s10086-009-1029-1.

- Missoum, K.; Belgacem, M.N.; Bras, J. Nanofibrillated cellulose surface modification: A review. Materials 2013, 6, 1745–1766, doi:10.3390/ma6051745.

- Andberg, M.; Penttilä, M.; Saloheimo, M. Swollenin from Trichoderma reesei exhibits hydrolytic activity against cellulosic substrates with features of both endoglucanases and cellobiohydrolases. Bioresour. Technol. 2015, 181, 105–113, doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2015.01.024.

- Long, L.; Tian, D.; Hu, J.; Wang, F.; Saddler, J. A xylanase-aided enzymatic pretreatment facilitates cellulose nanofibrillation. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 243, 898–904, doi:10.1016/j.biortech.2017.07.037.

- Henriksson, M.; Henriksson, G.; Berglund, L.A.; Lindström, T. An environmentally friendly method for enzyme-assisted preparation of microfibrillated cellulose (MFC) nanofibers. Eur. Polym. J. 2007, 43, 3434–3441, doi:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2007.05.038.

- Fraschini, C.; Chauve, G.; Bouchard, J. TEMPO-mediated surface oxidation of cellulose nanocrystals (CNCs). Cellulose 2017, 24, 2775–2790, doi:10.1007/s10570-017-1319-5.

- Gamelas, J.A.F.; Pedrosa, J.; Lourenço, A.F.; Mutjé, P.; González, I.; Chinga-Carrasco, G.; Singh, G.; Ferreira, P.J.T. On the morphology of cellulose nanofibrils obtained by TEMPO-mediated oxidation and mechanical treatment. Micron 2015, 72, 28–33, doi:10.1016/j.micron.2015.02.003.

- Medronho, B.; Andrade, R.; Vivod, V.; Ostlund, A.; Miguel, M.G.; Lindman, B.; Voncina, B.; Valente, A.J.M. Cyclodextrin-grafted cellulose: Physico-chemical characterization. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 93, 324–330, doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2012.08.109.

- Aulin, C.; Shchukarev, A.; Lindqvist, J.; Malmström, E.; Wågberg, L.; Lindström, T. Wetting kinetics of oil mixtures on fluorinated model cellulose surfaces. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2008, 317, 556–567, doi:10.1016/j.jcis.2007.09.096.

- Kaboorani, A.; Riedl, B. Surface modification of cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) by a cationic surfactant. Ind. Crops Prod. 2015, 65, 45–55, doi:10.1016/j.indcrop.2014.11.027.

- Eyley, S.; Thielemans, W. Surface modification of cellulose nanocrystals. Nanoscale 2014, 6, 7764–7779, doi:10.1039/c4nr01756k.

- Larsson, E.; Sanchez, C.C.; Porsch, C.; Karabulut, E.; Wågberg, L.; Carlmark, A. Thermo-responsive nanofibrillated cellulose by polyelectrolyte adsorption. Eur. Polym. J. 2013, 49, 2689–2696, doi:10.1016/j.eurpolymj.2013.05.023.

- Hokkanen, S.; Bhatnagar, A.; Sillanpää, M. A review on modification methods to cellulose-based adsorbents to improve adsorption capacity. Water Res. 2016, 91, 156–173, doi:10.1016/j.watres.2016.01.008.

- Kalia, S.; Sabaa, M.W. Polysaccharide Based Graft Copolymers, Springer: Berlin, German, 2013, Volume 9783642365, ISBN 9783642365669.

- Wei, L.; McDonald, A.G.; Stark, N.M. Grafting of Bacterial Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) onto Cellulose via In Situ Reactive Extrusion with Dicumyl Peroxide. Biomacromolecules 2015, 16, 1040–1049, doi:10.1021/acs.biomac.5b00049.

- Tee, Y.B.; Talib, R.A.; Abdan, K.; Chin, N.L.; Basha, R.K.; Md Yunos, K.F. Thermally Grafting Aminosilane onto Kenaf-Derived Cellulose and Its Influence on the Thermal Properties of Poly(Lactic Acid) Composites. BioResources 2013, 8, 4468–4483, doi:10.15376/biores.8.3.4468-4483.

- Cheng, D.; Wen, Y.; Wang, L.; An, X.; Zhu, X.; Ni, Y. Adsorption of polyethylene glycol (PEG) onto cellulose nano-crystals to improve its dispersity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2015, 123, 157–163, doi:10.1016/j.carbpol.2015.01.035.