| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Anastasia Diakou | + 936 word(s) | 936 | 2021-01-18 10:26:55 | | | |

| 2 | Simone Morelli | + 5 word(s) | 941 | 2021-01-26 09:28:37 | | |

Video Upload Options

Felid cardiopulmonary nematodes belong to the superfamily Metastrongyloidea and mainly to the species Aelurostrongylus abstrusus, Troglostrongylus brevior, Oslerus rostratus (parasites of the airways), and Angiostrongylus chabaudi (parasite of the pulmonary artery and right chambers of the heart).

1. The recent rise of scientific interest

In the early 2010s, the identification of Troglostrongylus brevior (until then considered a parasite of wild felids) as a cause of verminous bronchopneumonia in domestic cats was acknowledged[1][2]. This triggered a cascade of surveys, data accumulation, and scientific publications that led to new insights in the chapter of felid cardiopulmonary nematodes[3]. This rise of scientific interest resulted in further studies not only of the "new" cat parasite T. brevior, but also of the known cat lungworm, Aelurostrongylus abstrusus, and led to the “re-discovery” of some other parasites with the apparent ability to infect domestic cats (Felis catus), i.e. Troglostrongylus subcrenatus[2], Oslerus rostratus[4][5] and Angiostrongylus chabaudi[6][7].

2. Questions answered, doubts solved, and new interrogations posed in the light of new data

The amount of data generated by recent studies on felid cardiopulmonary nematodes has provided answers to various questions triggered over the previous years[8][9]. These data rely on new microscopic, genetic, epizootiological, and biological findings.

Aelurostrongylus abstrusus remains the primary nematode affecting the respiratory system of domestic cats, but it can also infect wild felids, especially the European wildcat (Felis silvestris), under occasional epizootiological pressure[10][11][12][13].

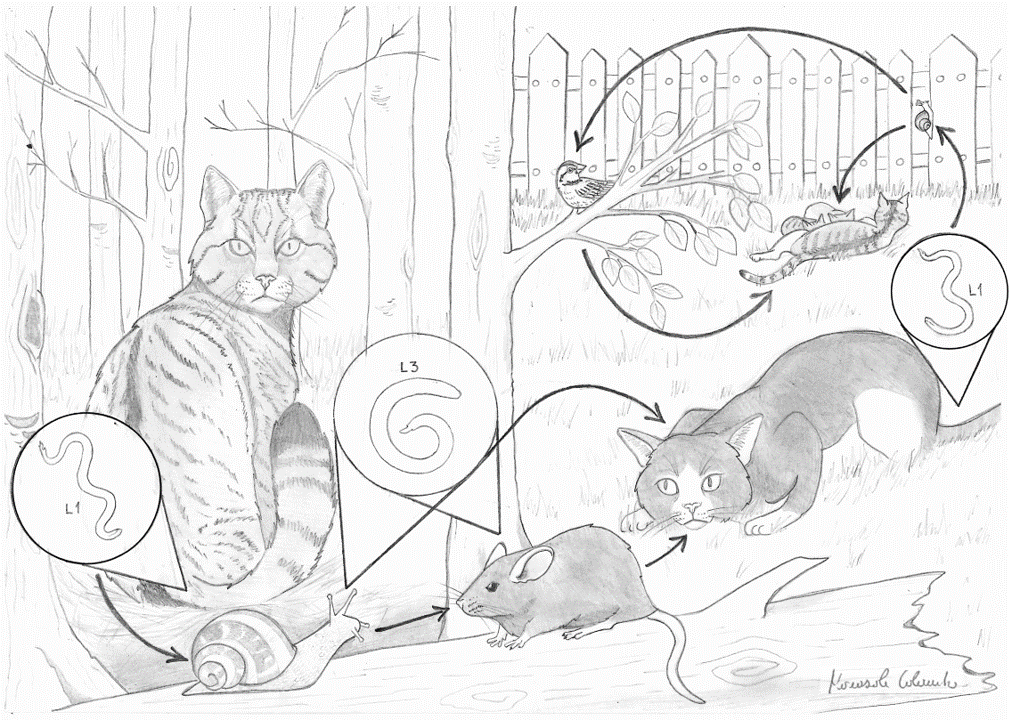

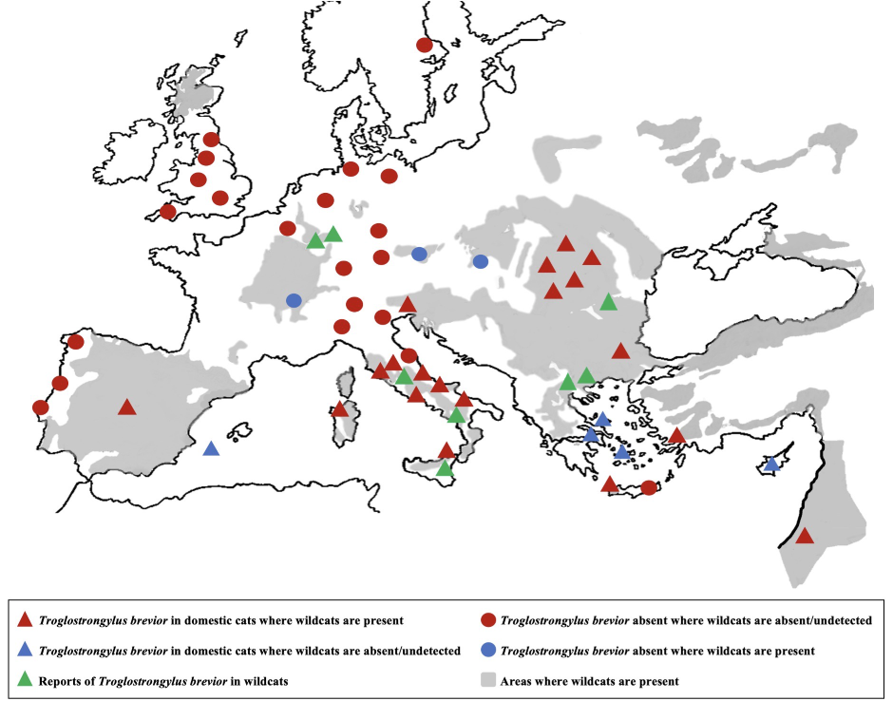

There is now evidence that the emergence of feline troglostrongylosis, is not due to misdiagnosis of past cases but rather relies on spillover from wildcats to domestic cats. Trogostrongylus brevior is now enzootic in populations of domestic cats of southern and insular Europe, as the European wildcat has played a crucial role in fostering its establishment[14][15][16][17][18] (Figures 1 and 2). The parasite may also circulate in domestic felids where the wild reservoir is absent. The movement of infected cats and the high adaptability of intermediate hosts to new areas may further spread the infection (Figure 3)[18][19]. It is also now documented that clinical troglostrongylosis is often severe and fatal, especially in kittens and young cats[20][21][22].

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the Troglostrongylus brevior spillover from the European wildcat (Felis silvestris) to the domestic cat (Felis catus). Drawing by Dr. Mariasole Colombo

Figure 2. Geographic distribution of Troglostrongylus brevior in Europe and the Middle East. The geographic distribution of Troglostrongylus brevior in domestic cats (red triangles) reflects the distribution area of wildcats (in grey). Troglostrongylus brevior has been sporadically reported in touristic spots where wildcats are absent or undetected (blue triangles). Green triangles indicate reports of Troglostrongylus brevior in wildcats; areas, where the nematode has been not found in the absence or presence of wildcats, are indicated by red and blue circles respectively.

Figure 3. Migration, travels, and islands suitability. a) Complete annual migration routes, indicated in different colors, of key bird species between Europe and Africa. Part of Figure 2 from under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. b) Statue of the famous Greek poet Nikos Kavadias (1910-1975), Argostoli harbour, Kefalonia, Greece (courtesy of Anna Votsi), who documented in his writings the tradition of cats living in boats and traveling long distances. c) Tourist traveling with her cat on a ferry boat. d) Cat on a boat traveling with its owners on holiday and moving between touristic spots (courtesy of Instagram @miss_rigby_boatkitty). e) Snails in a cat feeding station in Mykonos Island, Greece.

Trogostrongylus subcrenatus, O. rostratus, and A. chabaudi are only occasional parasites of F. catus. Their spreading in domestic cats is unlikely to happen under the current conditions, however, constant monitoring is essential. The actual existence of T. subcrenatus as a separate species needs to be confirmed by detailed microscopic and genetic analyses[2][3][23].

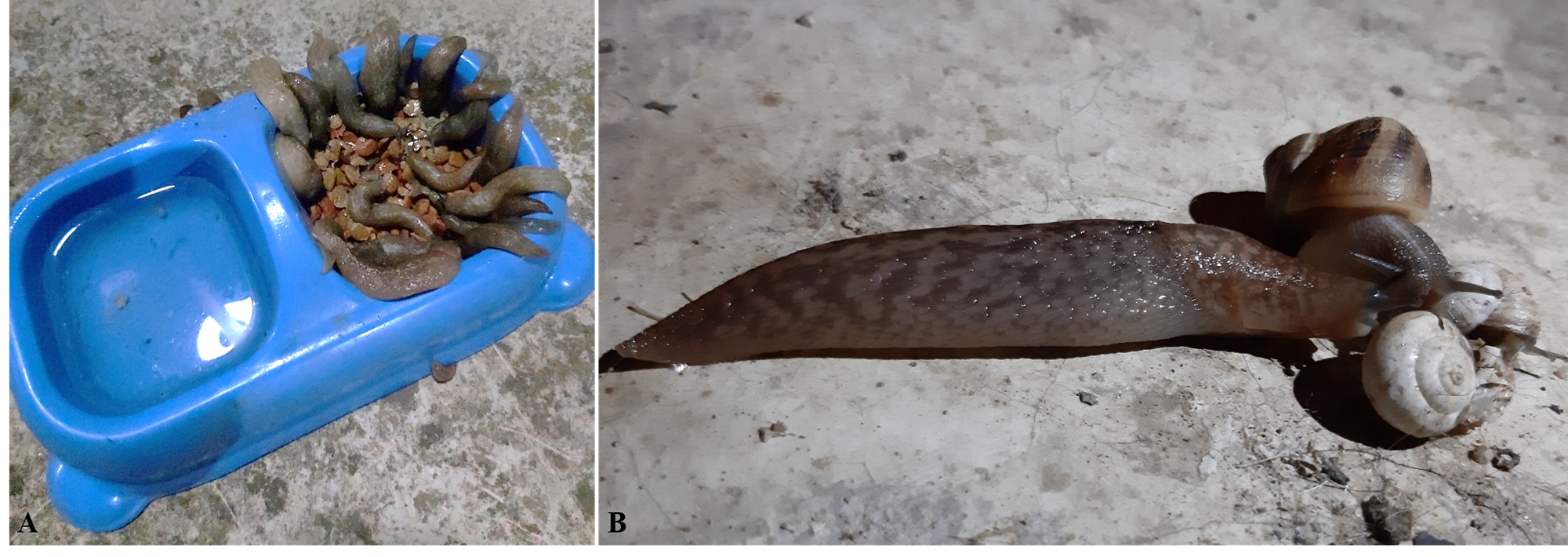

The impact of alternative routes of transmission, i.e. spontaneous release of L3 to the environment and the snail-to-snail L3 transmission[24][25][26] need to be evaluated in natural settings (Figure 4). Although vertical transmission of T. brevior has been documented[20][22], further data are warranted to elucidate how this occurs, i.e. in utero and/or lactogenically, and at what infection status of the maternal organism (established infection or infection acquired during pregnancy)[3].

Figure 4. Hypothesized phenomena contributing to the biology of felid cardiopulmonary metastrongyloids. An experiment suggested that metastrongyloid third stage larvae (L3) may be released in the environment but it has never been demonstrated if this happens in natural conditions. If so, infected molluscs drown in a cat bowl, or mingling in cat food (A) may be a potential source of infection. Another laboratory study proposed the “intermediesis”, i.e. the snail-to-snail transmission of L3, which is not known if occurs in the field. Regardless, it would be worth investigating if similar phenomena, e.g. gastropod cannibalism and interspecific predation (B), may also occur.

The European wildcat has ultimately been shown to be the natural host of T. brevior and A. chabaudi [9][10][27]. Aspects of the life cycle of A. chabaudi have been revealed and important information on the development of the nematode in intermediate hosts and on the mollusc species involved in its biology have been generated[19][27]. The role of angiostrongylosis in cat parasitology (i.e. rare and negligible) has been elucidated, though undetected cases cannot be excluded[6][7][23][28].

Knowledge on the identity of cardiopulmonary nematodes in wild felids is still meagre. As an example, the species Angiostrongylus felineus has been described only once, and only microscopically, in a jaguarundi in Brazil[29], thus it is practically unknown and worth of investigation. Parasitological studies on elusive felids are hard for the inherent hindrances in collecting suitable samples, but further studies are encouraged to implement knowledge of their cardiopulmonary parasitoses.

References

- Ryan Jefferies; Majda Globokar Vrhovec; Nicole Wallner; David Roman Catalan; Aelurostrongylus abstrusus and Troglostrongylus sp. (Nematoda: Metastrongyloidea) infections in cats inhabiting Ibiza, Spain. Veterinary Parasitology 2010, 173, 344-348, 10.1016/j.vetpar.2010.06.032.

- Emanuele Brianti; Gabriella Gaglio; Salvatore Giannetto; Giada Annoscia; Maria Stefania Latrofa; Filipe Dantas-Torres; Donato Traversa; Domenico Otranto; Troglostrongylus brevior and Troglostrongylus subcrenatus (Strongylida: Crenosomatidae) as agents of broncho-pulmonary infestation in domestic cats. Parasites & Vectors 2012, 5, 178-178, 10.1186/1756-3305-5-178.

- Donato Traversa; Simone Morelli; Angela Di Cesare; Anastasia Diakou; Felid Cardiopulmonary Nematodes: Dilemmas Solved and New Questions Posed. Pathogens 2021, 10, 30, 10.3390/pathogens10010030.

- Emanuele Brianti; Gabriella Gaglio; Ettore Napoli; Luigi Falsone; Alessio Giannelli; Giada Annoscia; Antonio Varcasia; Salvatore Giannetto; Giuseppe Mazzullo; Domenico Otranto; et al. Feline lungworm Oslerus rostratus (Strongylida: Filaridae) in Italy: first case report and histopathological findings. Parasitology Research 2014, 113, 3853-3857, 10.1007/s00436-014-4053-z.

- Antonio Varcasia; Emanuele Brianti; C. Tamponi; A. P. Pipia; P. A. Cabras; M. Mereu; Filipe Dantas-Torres; A. Scala; D. Otranto; Simultaneous infection by four feline lungworm species and implications for the diagnosis. Parasitology Research 2014, 114, 317-321, 10.1007/s00436-014-4207-z.

- Antonio Varcasia; Claudia Tamponi; Emanuele Brianti; Piera Angela Cabras; Roberta Boi; Anna Paola Pipia; Alessio Giannelli; Domenico Otranto; Antonio Scala; Angiostrongylus chabaudi Biocca, 1957: a new parasite for domestic cats?. Parasites & Vectors 2014, 7, 588, 10.1186/s13071-014-0588-1.

- Donato Traversa; Elvio Lepri; Fabrizia Veronesi; Barbara Paoletti; Giulia Simonato; Manuela Diaferia; Angela Di Cesare; Metastrongyloid infection by Aelurostrongylus abstrusus, Troglostrongylus brevior and Angiostrongylus chabaudi in a domestic cat. International Journal for Parasitology 2015, 45, 685-690, 10.1016/j.ijpara.2015.05.005.

- Donato Traversa; Angela Di Cesare; Feline lungworms: what a dilemma. Trends in Parasitology 2013, 29, 423-430, 10.1016/j.pt.2013.07.004.

- Angela Di Cesare; Fabrizia Veronesi; Donato Traversa; Felid Lungworms and Heartworms in Italy: More Questions than Answers?. Trends in Parasitology 2015, 31, 665-675, 10.1016/j.pt.2015.07.001.

- Fabrizia Veronesi; Donato Traversa; Elvio Lepri; Giulia Morganti; Francesca Vercillo; Dorian Grelli; Rudi Cassini; Marianna Marangi; Raffaella Iorio; Bernardino Ragni; et al.Angela Di Cesare OCCURRENCE OF LUNGWORMS IN EUROPEAN WILDCATS (FELIS SILVESTRIS SILVESTRIS) OF CENTRAL ITALY. Journal of Wildlife Diseases 2016, 52, 270-278, 10.7589/2015-07-187.

- Diakou, A.; Migli, D.; Dimzas, D.; Di Cesare, A.; Youlatos, D.; Lymberakis, P.; Traversa, D. Parasites of European wildcats (Felis silvestris silvestris) in Greece. Proceedings of the International Congress on the Zoogeography and Ecology of Greece and Adjacent Regions, Thessaloniki, Greece, 27–29 June 2019; pp. 42.

- Angela Di Cesare; Francesca Laiacona; Raffaella Iorio; Marianna Marangi; Alessia Menegotto; Aelurostrongylus abstrusus in wild felids of South Africa. Parasitology Research 2016, 115, 3731-3735, 10.1007/s00436-016-5134-y.

- Anastasia Diakou; Dimitris Dimzas; Christos Astaras; Ioannis Savvas; Angela Di Cesare; Simone Morelli; Κostantinos Neofitos; Despina Migli; Donato Traversa; Clinical investigations and treatment outcome in a European wildcat (Felis silvestris silvestris) infected by cardio-pulmonary nematodes. Veterinary Parasitology: Regional Studies and Reports 2020, 19, 100357, 10.1016/j.vprsr.2019.100357.

- Angela Di Cesare; Gabriella Di Francesco; Antonio Frangipane Di Regalbono; Claudia Eleni; Claudio De Liberato; Giuseppe Marruchella; Raffaella Iorio; Daniela Malatesta; Maria Rita Romanucci; Laura Bongiovanni; et al.Rudi CassiniDonato Traversa Retrospective study on the occurrence of the feline lungworms Aelurostrongylus abstrusus and Troglostrongylus spp. in endemic areas of Italy. The Veterinary Journal 2015, 203, 233-238, 10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.12.010.

- Donato Traversa; Simone Morelli; Rudi Cassini; Paolo E. Crisi; Ilaria Russi; Eleonora Grillotti; Simone Manzocchi; Giulia Simonato; Paola Beraldo; Antonio Viglietti; et al.Cesare De TommasoCarlo PezzutoFabrizio PampuriniRoland SchaperAntonio Frangipane Di Regalbono Occurrence of canine and feline extra-intestinal nematodes in key endemic regions of Italy. Acta Tropica 2019, 193, 227-235, 10.1016/j.actatropica.2019.03.009.

- Alessio Giannelli; Gioia Capelli; Anja Joachim; Barbara Hinney; Bertrand Losson; Zvezdelina Kirkova; Magalie René-Martellet; Elias Papadopoulos; Róbert Farkas; Ettore Napoli; et al.Emanuele BriantiClaudia TamponiAntonio VarcasiaAna Margarida AlhoLuís Madeira De CarvalhoLuís CardosoCarla MaiaViorica MirceanAndrei Daniel MihalcaGuadalupe MiróManuela SchnyderCinzia CantacessiVito ColellaMaria Alfonsa CavaleraMaria Stefania LatrofaGiada AnnosciaMartin KnausLénaïg HalosFrederic BeugnetDomenico Otranto Lungworms and gastrointestinal parasites of domestic cats: a European perspective. International Journal for Parasitology 2017, 47, 517-528, 10.1016/j.ijpara.2017.02.003.

- Anastasia Diakou; Angela Di Cesare; Luciano Antunes Barros; Simone Morelli; Lénaïg Halos; Fred Beugnet; Donato Traversa; Occurrence of Aelurostrongylus abstrusus and Troglostrongylus brevior in domestic cats in Greece. Parasites & Vectors 2015, 8, 1-6, 10.1186/s13071-015-1200-z.

- Anastasia Diakou; Dimitra Sofroniou; Angela Di Cesare; Panagiotis Kokkinos; Donato Traversa; Occurrence and zoonotic potential of endoparasites in cats of Cyprus and a new distribution area for Troglostrongylus brevior. Parasitology Research 2017, 116, 3429-3435, 10.1007/s00436-017-5651-3.

- Dimitris Dimzas; Simone Morelli; Donato Traversa; Angela Di Cesare; Yoo Ree Van Bourgonie; Karin Breugelmans; Thierry Backeljau; Antonio Frangipane Di Regalbono; Anastasia Diakou; Intermediate gastropod hosts of major feline cardiopulmonary nematodes in an area of wildcat and domestic cat sympatry in Greece. Parasites & Vectors 2020, 13, 1-12, 10.1186/s13071-020-04213-z.

- Donato Traversa; Leonardo Della Salda; Anastasia Diakou; Chiara Sforzato; Mariarita Romanucci; Antonio Frangipane Di Regalbono; Raffaella Lorio; Valentina Colaberardino; Angela Di Cesare; Fatal Patent Troglostrongylosis In A Litter of Kittens. Journal of Parasitology 2018, 104, 418-423, 10.1645/17-172.

- Paolo E Crisi; Angela Di Cesare; Andrea Boari; Feline Troglostrongylosis: Current Epizootiology, Clinical Features, and Therapeutic Options. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2018, 5, 126, 10.3389/fvets.2018.00126.

- Marcos Antônio Bezerra-Santos; Jairo Alfonso Mendoza-Roldan; Francesca Abramo; Riccardo Paolo Lia; Viviana Domenica Tarallo; Harold Salant; Emanuele Brianti; G. Baneth; Domenico Otranto; Transmammary transmission of Troglostrongylus brevior feline lungworm: a lesson from our gardens. Veterinary Parasitology 2020, 285, 109215-109215, 10.1016/j.vetpar.2020.109215.

- Angela Di Cesare; Simone Morelli; Mariasole Colombo; Giulia Simonato; Fabrizia Veronesi; Federica Marcer; Anastasia Diakou; Roberto D'angelosante; Nikola Pantchev; Evanthia Psaralexi; et al.Donato Traversa Is Angiostrongylosis a Realistic Threat for Domestic Cats?. Frontiers in Veterinary Science 2020, 7, 195, 10.3389/fvets.2020.00195.

- Gary Conboy; Nicole Guselle; Roland Schaper; Spontaneous Shedding of Metastrongyloid Third-Stage Larvae by Experimentally Infected Limax maximus. Parasitology Research 2017, 116, 41-54, 10.1007/s00436-017-5490-2.

- Vito Colella; Alessio Giannelli; Emanuele Brianti; Rafael Antonio Nascimento Ramos; Cinzia Cantacessi; Filipe Dantas-Torres; Domenico Otranto; Feline lungworms unlock a novel mode of parasite transmission. Scientific Reports 2015, 5, 13105, 10.1038/srep13105.

- Alessio Giannelli; Vito Colella; Francesca Abramo; Rafael Antonio Do Nascimento Ramos; Luigi Falsone; Emanuele Brianti; Antonio Varcasia; Filipe Dantas-Torres; Martin Knaus; Mark T. Fox; et al.Domenico Otranto Release of Lungworm Larvae from Snails in the Environment: Potential for Alternative Transmission Pathways. PLOS Neglected Tropical Diseases 2015, 9, e0003722, 10.1371/journal.pntd.0003722.

- Anastasia Diakou; Dimitra Psalla; Despina Migli; Angela Di Cesare; Dionisios Youlatos; Federica Marcer; Donato Traversa; First evidence of the European wildcat (Felis silvestris silvestris) as definitive host of Angiostrongylus chabaudi. Parasitology Research 2015, 115, 1235-1244, 10.1007/s00436-015-4860-x.

- Emily Katharina Gueldner; Carole Schuppisser; Nicole Borel; Monika Hilbe; Manuela Schnyder; First case of a natural infection in a domestic cat (Felis catus) with the canid heart worm Angiostrongylus vasorum. Veterinary Parasitology: Regional Studies and Reports 2019, 18, 100342-100342, 10.1016/j.vprsr.2019.100342.

- Fabiano Matos Vieira; Luís C Muniz-Pereira; Sueli De Souza Lima; Antonio H. A. Moraes Neto; Erick V. Guimarães; José Luis Luque; A New Metastrongyloidean Species (Nematoda) Parasitizing Pulmonary Arteries ofPuma(Herpailurus)yagouaroundi(É. Geoffroy, 1803) (Carnivora: Felidae) from Brazil. Journal of Parasitology 2013, 99, 327-331, 10.1645/ge-3171.1.