| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | László Csernoch | + 5042 word(s) | 5042 | 2021-01-12 05:05:46 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | -2 word(s) | 5040 | 2021-01-21 04:28:47 | | |

Video Upload Options

Muscle dystrophy is a muscle disease that leads to a progressive loss of muscle mass and a weakened musculoskeletal system in accordance with age of onset, severity, and the group of muscles affected.

1. Introduction

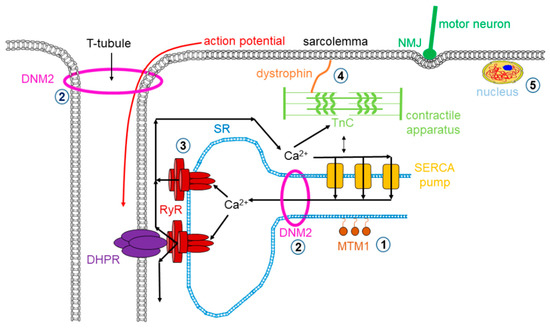

Dystrophy is an umbrella name that encompasses more than 30 genetic disorders that progress over time, leading to degeneration and weakness of the muscles. The phenotype of muscular dystrophy is an endpoint that arises from a disparate set of genetic and biochemically heterogeneous pathways. Genes associated with muscular dystrophies encode proteins of the plasma membrane (sarcolemma), terminal cisternae, extracellular matrix, and the sarcomere, as well as nuclear membrane components (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Mutations in skeletal muscle causing muscle disorders. ➀. Altered lipid phosphatase activity of MTM1; ➁. defects in microtubule dynamics or vesicular traffic (DNM2); ➂. defective calcium release from the SR via RyRs; ➃. mutated or missing dystrophin; ➄. defects in alternative splicing due to MBLN1, CELF1 and DUX4 malfunction. (MTM1: myotubularin 1; DNM2: dynamin 2; SR: sarcoplasmic reticulum; RyR: ryanodine receptor; MBLN1: muscle blind-like; CELF: CUGBP/Elav-like factors; DUX4: homebox protein 4; DHPR: dihydropyridine receptor; NMJ: neuromuscular junction; SERCA: sarco(endo)plasmic reticulum calcium pump).

Myopathies are a diversified family of disorders characterized by pathological structure and/or the functioning of skeletal muscles. Inherited myopathies include a clinically, histopathologically, and genetically heterogeneous group of rare genetic muscle diseases that are characterized by architectural anomalies in the muscle fibers.

2. Muscular Dystrophies

Muscular dystrophies (MDs) are a group of inherited disorders in which the voluntary muscles that control movement, in some instances the heart muscles and eventually the diaphragm, progressively weaken and lose their ability to maintain proper function. There are more than 30 types of MDs that vary in severity, symptoms, and causes. In recent years, the classification of MDs has been adjusted in order to correspond to the newly available information related to the primary protein dysfunctions and their localizations. As a consequence, by convention, the MDs had been classified according to the main clinical and biopsy findings, age of onset, and rate of progression into nine major forms: (1) Becker, (2) congenital, (3) Duchenne, (4) distal, (5) Emery–Dreifuss, (6) facioscapulohumeral, (7) limb–girdle, (8) myotonic, and (9) oculopharyngeal muscular dystrophy. In the present review, we tackle the most common forms of MDs in humans.

2.1. Dystrophinopathies

Dystrophinopathies cover a spectrum of X-linked muscle diseases ranging from mild to severe forms that include Duchenne muscular dystrophy (DMD), Becker muscular dystrophy (BMD), and DMD-associated dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM). DMD/BMD are neuromuscular genetic disorders characterized by progressive muscle degeneration, weakness, and wasting due to the alterations of a critical muscle protein called dystrophin, which is a relatively long (110 nm), rod-shaped intracellular protein localized at the cytoplasmic face of the sarcolemma in cardiac and skeletal muscles [1][2]. Dystrophin connects γ-actin of the subsarcolemmal cytoskeleton system to a complex of proteins in the surface membrane (dystrophin protein complex, DPC) and helps keep the muscle cell intact and orchestrates the transmission of force laterally across the muscle during contraction (see Figure 1). Growing evidence suggests that dystrophin also has a major role in regulating signaling pathways that activate nitric oxide (NO) production, Ca2+ entry, and the production of reactive oxygen species (ROS). The absence or reduced expression of dystrophin beside other members of the DPC complex causes dystrophinophathies.

DMD is the most common muscular dystrophy in children affecting primarily boys due to classical X-linked recessive genetics according to which males who carry the mutation express the disease while females are carriers. The incidence of DMD is approximately 1 in 3500 [3][4][5][6]. DMD symptom onset is in early childhood, usually between ages 2 and 6. The symptoms of DMD include decreased muscle size accompanied by progressive weakness and atrophy of skeletal and heart muscles. Early signs of DMD are muscle weakness of weight-bearing muscles and may include delayed ability to sit, stand, or walk, difficulties learning to speak, and general cognitive impairment. Most children with DMD use a wheelchair by their early teens. Heart and breathing problems also begin in the teen years, leading to serious life-threatening complications, and patients usually die in the third or fourth decade due to respiration or cardiac failure.

Frame-shift mutations or other genetic rearrangement in the dystrophin gene abolish protein expression that disturbs the connection between the cytoskeleton and the extracellular matrix, making muscle fibers more susceptible to contraction-induced membrane damage. As a result, the uncontrolled influx of calcium ions occurs inevitably, leading to progressive myofiber degeneration [7][8]. These pathologic processes are accompanied by chronic inflammation and fibrosis [9], as evidenced by macrophage infiltration [10]. In DMD, skeletal muscles active myofiber necrosis, and cellular infiltration can be histologically identified, furthermore regenerating myofibers containing centrally located nuclei, and a large variety of myofiber sizes are often detected. This phenotype is particularly pronounced in the diaphragm, which undergoes progressive degeneration and myofiber loss, causing an approximately 5-fold reduction in muscle isometric strength [11].

In-frame deletions often generate truncated dystrophin and result in BMD characterized by skeletal muscle weakness with milder symptoms and later onset that appear between the ages of 2 and 16 but in some cases as late as the twenties. Its incidence has been estimated to be between 1 in 30,000 male births [12][13].

Plentiful mouse models have been developed to better understand the basic molecular biology of DMD. Currently, there are nearly 60 different animal models for DMD, and the list keeps growing. For a comprehensive lineup, see Table 1 and the review by McGreevey and colleagues [14]. The TREAT-NMD Alliance (https://treat-nmd.org/research-overview/preclinical-research/) is an initiative to improve preclinical trial design and execution for the most common mouse models of DMD, spinal muscular atrophy (SMA), and congenital muscular dystrophy.

Table 1. Mouse models of Duchenne muscular dystrophy.

| Model System | Genetic Changes in the Mouse Model/Mutation(s) | Genetic Similarity/Genetic Background | Likeliness of Phenotype and Symptoms | References | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advantage | Disadvantage | Advantage | Disadvantage | |||

| Dystrophin-deficient mice | ||||||

| mdx Albino mdx mdx/BALB/c mdx/BL6 mdx/C3H mdx/DBA2 mdx/FVB |

Exon 23 point mutation. | On the C57BL/10 background. mdx on the Albino background. mdx on the BALB/c background. mdx on the C57BL/6 background. mdx on the C3H background. mdx on the DBA2 background. mdx on the FVB background. |

The diaphragm shows progressive deterioration as in humans. More severe dystrophic signs. |

Minimal clinical symptoms, lifespan reduced by only 25% compared to human DMD. | [15][16][17][18][19] | |

| mdx2cv mdx3cv mdx4cv mdx5cv |

Intron 42 point mutation. Intron 65 point mutation. Exon 53 point mutation. Exon 10 point mutation. |

On the C57BL/6 background. | Chemically induced mutation. all dystrophin isoforms eliminated. |

Fewer revertant fibers. Severe disease signs. |

[20] | |

| CRKHR1 | Unsequenced, dystrophin deficiency confirmed by immunofluorescence staining. | On the C3H background. | ENU chemically induced mutation. | Elevated CK, centrally nucleated myofibers, and dystrophin deficiency. | [21] | |

| mdx52 | Exon 52 deletion. | On the C57BL/6 background hot spot mutation. |

Targeted inactivation. | [22] | ||

| mdxβgeo | Insertion of the β-geo gene trap cassette in intron 63. | LacZ replaced the CR and CT domain. | All dystrophin isoforms are mutated. | [23] | ||

| DMD-null | Entire DMD gene deletion. | Cre-loxP system. | All dystrophin isoforms are eliminated. | [24] | ||

| Dp71-null | Insertion of the β-geo cassette in intron 62. | Selective elimination of Dp71. | Dp71 deficiency is associated with early cataract formation in mice. | [25][26] | ||

| Dup2 | Exon 52 duplication. | On the C57BL/6 background. | [27] | |||

| Immun-deficient mdx mice | ||||||

| NSG-mdx4cv | Prkdc and IL2rb double deficient. | On the mdx4cv background. | Innate immunity deficient. | B, T, and NK cell deficient. | [28] | |

| Rag2 IL2rb Dmd | Rag2 and IL2rb double deficient. | On the mdx βgeo background. | B, T, and NK cell deficient. No revertant fibers. |

[29][30] | ||

| Scid mdx | Prkdc deficient. | On the mdx background. | B and T cell deficient. | [31] | ||

| W41 mdx | C-kit receptor deficient | On the mdx background | Haematopoietic deficient. | Optimal for bone marrow cell therapy studies. | [32] | |

| Phenotypic dko mice | ||||||

| α7/dystrophin dko or mdx/α7–/– | α7/dystrophin double deficient. | Severe dystrophic phenotype. | [33][34] | |||

| Adbn–/– mdx | αdystrobrevin/dystrophin double deficient. | Severe dystrophic phenotype. | [35] | |||

| Cmah-mdx | Cmah/dystrophin double deficient. | Severe dystrophic phenotype. “humanized” |

[36] | |||

| d-dko | δ-sarcoglycan/dystrophin double deficient. | Severe dystrophic phenotype. | [37] | |||

| Desmin-/- mdx4cv | desmin/dystrophin double deficient. | Severe dystrophic phenotype. | [38] | |||

| Dmdmdx/Largemyd | like-glycosyltransferase/dystrophin deficient. | Severe dystrophic phenotype. | [39] | |||

| DMD null; Adam8-/- | ADAM8 deficient and entire DMD gene deletion. | On the DMD-null background. | The injured myofibers are not efficiently removed in DMD null. | [40] | ||

| dysferlin/dystrophin dko | dysferlin/dystrophin double deficient. | Severe dystrophic phenotype. | [41][42] | |||

| Il-10-/-/mdx | interleukin-10/dystrophin double deficient. | On the mdx background. | Severe dystrophic phenotype and marked cardiomyopathy. | [43] | ||

| mdx/mTR | telomerase RNA/dystrophin double deficient. | Premature depletion of myofiber repair. | Severe dystrophic phenotype. | [44] | ||

| mdx:MyoD-/- | MyoD/dystrophin double deficient. | MyoD is only expressed in skeletal muscle. | Severe dystrophic phenotype and prominent dilated cardiomyopathy. | MyoD mutations do not occur in human DMD. | [45] | |

| mdx:utrophin-/- | utrophin/dystrophin double deficient. | Targeted mutation at the utrophin CR domain/exon 7. | Severe dystrophic phenotype with cardiomyopathy, cardiac fibrosis, LV dilation. | [35][46] | ||

| PAI-1-/--mdx | plasminogen activator inhibitor-1/dystrophin double deficient. | Early onset fibrosis and higher CK. | [47] | |||

| Transgenic mdx mice | ||||||

| full-length dystrophin TG mdx | transgenic over-expression of full-length dystrophin. | On the mdx background. | Over-expression does not harm muscle rather it shows protection. | [48][49][50] | ||

| Dp71 TG mdx | transgenic over-expression of Dp71. | On the mdx background. | Severe disease signs. | [51][52] | ||

| Dp116 TG mdx4cv Dp116:mdx:utrophin-/- |

transgenic over-expression of Dp116. | On the mdx4cv background on the utrophin/dystrophin dko background. |

Severe disease signs. Improved lifespan. |

No change in histopathology, CK, and specific force development. | [53][54] | |

| Dp260 TG mdx Dp260 mdx/utrn-/- |

transgenic over-expression of Dp260. | On the mdx background on the utrophin/dystrophin dko background. |

Slightly improved histopathology. Severe lethal phenotype was converted to a mild myopathy. |

No improvement of specific force. | [55][56] | |

| micro-dystrophin TG | transgenic over-expression of synthetic micro-dystrophin gene. | On the mdx background. | Improved protection against disease signs. | No restoration of nNOS. | [57][58][59][60] | |

| Fiona | transgenic over-expression of full-length dystrophin gene. | On the mdx background. | Improved protection against disease signs. | No restoration of nNOS. | [61][62] | |

| laminin α1 TG mdx | transgenic over-expression of laminin α1. | On the mdx background. | Similar phenotype as mdx. | No improvement but no harm. | [63] | |

With all its caveats, the most widely used animal model for DMD research is the C57BL/10ScSn-Dmdmdx/J (BL10-mdx; available from the Jackson laboratory, JL#001801) mouse in which the dystrophic phenotype arises because of a point mutation (C to T transition) in exon 23, which results in a stop codon and truncated dystrophin protein. This spontaneous mutation was discovered in the early 1980s in a colony of C57BL/10ScSn mice due to elevated serum creatine kinase (CK) and histological evidence of myopathy [15]. The mdx muscles seem more susceptible to contraction- and stretch-induced damage revealed as sarcolemmal tears [64]. Normal physiological control of calcium homeostasis is lost in mdx mice [65][66], and similar to the human condition, calcium levels are increased in myofibers isolated from mdx mice [67].

DMD is a multi-systemic condition affecting many parts of the body and resulting in atrophy of the skeletal, cardiac, and respiratory muscles. DMD disease progression in mdx mice has several distinctive phases. In the first 2 weeks, the mdx muscle is indistinguishable from that of normal mice. Between 3 and 6 weeks, it undergoes astonishing necrosis. Subsequently, the majority of skeletal muscle enters a relatively robust regeneration phase. As a hallmark of the disease, mdx limb muscles often become hypertrophic during this phase. The diaphragm is an exception, as it shows progressive deterioration, as seen in affected humans [11]. Severe dystrophic phenotypes, such as muscle wasting, scoliosis, and heart failure do not occur until mdx mice are 15 months or older [68][69][70][71][72][73]. Despite being deficient for dystrophin, mdx mice display overall minimal clinical symptoms; their lifespan is only reduced by ≈25% (vs. 75% decrease in humans) without obvious signs of dilated cardiomyopathy [14][37]. The robust skeletal muscle regeneration might explain somewhat the slowly progressive phenotype observed in mdx mice.

The mdx mouse has been crossed to several different genetic backgrounds, including the Albino, BALB/c, C3H, C57BL/6, DBA2, and FVB strains; several immune-deficient mdx strains were also engineered (see Table 1). Phenotypic variation has been observed in different backgrounds. Several other dystrophin-deficient lines (Dup2, DMD-null, Dp71-null, mdx52, and mdxβgeo) were also created using various genetic engineering techniques. The DMD-null mouse was created by deleting the entire DMD genomic region using the Cre-loxP technology [24] resulting in the ablation dystrophin isoforms expression in all tissues. Further models (mdxcv) were created by chemical mutagenesis programs by treating mice with N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea, a chemical mutagen, so that each strain carries a different point mutation [20][74]. By eliminating myogenic differentiation 1 (MyoD), a master myogenic regulator, from mdx mice, Megeney et al. obtained a MyoD/dystrophin double-mutant mouse that shows marked myopathy, dilated cardiomyopathy, and premature death [45][46][75]. Another similar approach was the generation of telomerase/mdx double-mutant mice (mTR/mdx) that show more severe muscle wasting and cardiac defects [44][76].

Two other proteins, utrophin and α7-integrin, fulfill the same function as dystrophin, and their relative expression is upregulated in mdx mice. The genetic elimination of utrophin, which is expressed along the sarcolemma in developing muscle, exhibits 80% homology and shares structural and functional motifs with dystrophin and α7-integrin; their deletion in mdx mice lead to the creation of utrophin/dystrophin and integrin/dystrophin double-knockout (dko) mice, respectively [33][34][35][46][77]. The dko mice show much more severe muscle disease symptoms (similar to or even worse than that of humans with DMD); however, they are difficult to generate and care for. Utrophin heterozygous mdx mice might represent an intermediate model between the extreme dko mice and mildly affected mdx mice [78][79].

Second mutations have been introduced to “humanize” mice (e.g., inactivation of cytidine monophosphate sialic acid hydrolase (Cmah)) and to mutate genes involved in cytoskeleton-ECM interactions (e.g. desmin and laminin); however, the introduction of a second mutation not present in human DMD turned out to produce a much more severe phenotype and complicated data interpretation [14][36][46][80].

To test if the “humanization” of telomere lengths could recapitulate the DMD disease phenotype, the mdx4cv/mTRG2 dko mice were generated, which seem to recapitulate the best of both the skeletal muscle and cardiovascular features of human DMD [44]. Nevertheless, there are still a few tenable therapies for DMD, so the need for appropriate mouse models more similar to the mdx model is emphasized. Even with an improved delivery of promising strategies such as gene editing or exon skipping, testing must be done in mice with the full spectrum of DMD pathology.

Dysferlinopathies are caused by the lack of functional dysferlin, which is a key protein involved in membrane repair processes causing Myoshi myopathy or dysferlin-related limb girdle muscular dystrophy (LGMD R2) [81]. The dysferlin-deficient mice (dysf-/-) replicate well human dysferlinopathies, showing similarities with the human condition although with milder histopathological aspects. Due to space restrictions, we did not further elaborate on these mouse models (for a comprehensive review, see [82] and more recently [83].

2.2. Myotonic Dystrophy

Myotonic dystrophy (DM) is an autosomal dominantly inherited disorder and the most prevalent form of muscular dystrophy in adulthood. Clinical characterization of the disease was done first by Steiner in 1909. DM is a complex genetic disease with diverse symptoms affecting multiple organs, such as skeletal muscle, cardiac muscle, the endocrine and gastrointestinal system, reproductive system, and central nervous system (CNS). Symptoms range from muscle weakness and wasting both in skeletal muscle and in heart, arrhythmias, or conduction abnormalities, disorders in the function of the neuromuscular junction, neurologic impairment such as excessive daytime sleepiness and motivation deficit, insulin resistance, cataracts, and male infertility. There are two major forms of the disease: myotonic dystrophy type I (DM1 or Steiner’s disease) and myotonic dystrophy type II (DM2 or proximal myotonic myopathy), which are associated to partially similar clinical appearances but distinct genetic defects [57].

Several hypotheses have been suggested to explain the complex symptoms of DM. The genetic background responsible for classic myotonic dystrophy documented by Steiner was discovered in 1992. An expansion of a CTG trinucleotide repeat in the 3′ untranslated region of the dystrophia myotonica protein kinase gene (DMPK) has been identified, which is a mutation that has been transcribed into RNA but not translated into protein [57]. Based on DMPK haploinsufficiency theory, the expanded repeats inhibit DMPK mRNA or protein production, which is in agreement with observation in DM1 patient muscle and cell cultures demonstrating a decreased expression of DMPK mRNA and protein [84]. On the other hand, DMPK-knockout mice did not display myotonia but rather mild myopathy [85]. Although DMPK haploinsufficiency alone is not sufficient to explain the features of DM1, the CTG repeats might influence the expression of neighboring genes as well. The haploinsufficiency of SIX5 and of other adjacent genes such as myotonic dystrophy gene with tryptophan and aspartic acid (WD) repeats, DMWD [86], and the FCGRT gene, encoding the Immunoglobulin G Fc Fragment Receptor and Transporter, has also been suggested to contribute to DM1 pathogenesis [87]. Indeed, Six5 knockout mice develop cataracts [88][89] but without any muscular deficiency. The next concept was the RNA gain-of-function hypothesis assuming that the mutant RNA transcribed from the expanded allele is capable of inducing symptoms of the disease. The HSALR transgenic mouse model (among others) confirms this theory [90]. In HSALR mice 250 CTG repeats were expressed in the 3′ end of the human skeletal α-actin gene that implied myotonia and muscle degeneration characteristic in DM1 without a multisystem phenotype.

DM2 was identified in 1998 with a different genetic mutation from that of DM1 [91]. In 2001, DM2 was reported as a result of CCTG repeats within intron 1 of the nucleic acid-binding protein (CNBP) gene (known also as zinc finger 9 gene, ZNF9) [92]. In both types of DM, there is a nucleotide repeat expansion; however, completely different genes are affected. Nevertheless, DM1 and DM2 have similar symptoms bringing up the idea of a common pathogenic mechanism. One candidate is a process through interaction with RNA-binding proteins. The transcripts with nucleotide repeat expansions can accumulate in the nucleus (see Figure 1) and form RNA aggregates/foci interfering with protein families such as the muscleblind-like (MBNL), CUGBP/Elav-like factors (CELF), and the RNA binding Fox (RBFOX) being the most important splicing regulators in skeletal muscle [93][94][95].

MBNL1 is sequestered on the expanded CUG repeats producing a loss of function, while CELF1 is upregulated due to the activation of protein kinase C, leading to its stabilization. These processes result in irregular splicing profiles of MBNL1- and CELF1-regulated transcripts in adult skeletal muscle and heart, or even during embryonic to adult switch in the splicing pattern. MBNL1 (Mbnl1ΔE3/ΔE3) knockout mice with targeted deletion of MBNL1 exon 3—where an RNA-binding motif is located—underpin this model, since these animals reproduce several features of DM including muscle, eye, and RNA splicing disorders (alternative splicing regulation in the brain is slightly affected, it depends mainly on the loss of MBNL2) [96]. Moreover, the adeno-associated virus-mediated overexpression of MBNL1 in HSALR mice is able to lessen the myotonia [24]. Verification also arises from the tissue-specific induction of CELF1 overexpression in adult mouse skeletal muscle, where muscle impairment detected in DM1 has been reproduced [97], while CELF1 overexpression in the heart leads to cardiac abnormalities similar to DM1 [98] (the role of CELF1 in DM2 is not clarified). These phenotypes were related to miss-splicing. These animal models imply that the overexpression of toxic CTG or CCTG repeats, depletion of MBNL1, or overexpression of CELF1 would all eventuate in similar splicing alterations, which initiate downstream signaling pathways resulting in the phenotype and/or molecular background of myotonic dystrophies.

The modified splicing apparatus can affect other genes in diverse signal transduction pathways leading to disrupted protein synthesis or the presence of different protein isoforms and the modified localization of proteins. Focusing on muscle, an aberrant regulation of RNA-binding proteins causes splicing alterations in the voltage-gated chloride channel 1 (CLCN1) transcript resulting in myotonia with delayed muscle relaxation in skeletal muscle cells [57][99]. Alternative splicing defects of BIN1 (bridging integrator 1), a lipid-binding protein responsible for the biogenesis of the transverse (T) tubules, has also been associated with muscle weakness. The inactive form of BIN1 causes damages of the excitation–contraction coupling (ECC) [100]. Another protein concerned is the calcium channel CaV1.1. Mis-splicing of the CACNA1S gene contributes to muscle weakness. Alternative splicing of the genes encoding ryanodine receptor 1 (RyR1) and SERCA1 expression are also altered modifying contractility of the muscles [101]. Altered splicing of several other genes encoding structural proteins has also been described in DM, as a few examples: DTNA (encoding dystrobrevin-α), MYOM1 (encoding myomesin1), NEB (encoding nebulin), TNNT3 (encoding fast troponin T3), DMD (encoding dystrophin), MTMR1 (encoding myotubularin-related protein 1), and CAPN3 (encoding intracellular protease Calpain 3). Atypical splicing of the insulin receptor (IR) may take part in the formation of insulin resistance. The genes mentioned above represent just a few examples of the more than 30 miss regulated splicing identified in DM patient’s tissue samples or of the more than 60 aberrant splicing described in mice tissues [102].

According to the previously listed conditions, molecular, and genetic variations, an “overall DM” model system should meet several requirements. At this moment, none of the available mouse models recapitulates all aspects of DM (for a comprehensive list of these mouse models, see Table 2). At the same time, the mouse models generated so far provided us with a significant tool in understanding the disease mechanism. There are different approaches in the various models. The inactivation of DM genes, the overexpression of toxic CTG/CTGG repeats, the induced alterations in splicing through MBNL1 inactivation, or CELF1 overexpression have resulted in a transgenic mouse model that was suitable for the examination of different aspects of the disease. Despite the growing number of already identified transcripts and the increased amount of data on altered pathways, the precise mechanism of the DMs is poorly understood. The available and the new mouse models to be established in the future can help scientists to discover a disease-modifying therapy.

Table 2. Mouse models of myotonic dystrophies.

| Model System | Genetic Changes in the Mouse Model/Mutation(s) | Genetic Similarities/Genetic Background | Likeliness of Phenotype and Symptoms | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advantage | Disadvantage | Advantage | Disadvantage | ||

| DMPK KO | Reduced DMPK transcripts levels by inactivation of the DMPK gene. | Can be used to study relief pathways in DM pathogenesis. Lacks RNA toxicity and transcripts interactions. |

Increased possibility of cataracts, male infertility, and cardiac dysfunction. No characteristic symptoms on different organs. |

||

| Tg26 | Overexpression of normal DMPK gene with short, non-pathogenic CTG repeats. | Can be used to study the effect of normal DMPK in high expression levels. | The pathogenesis is vastly different from conventional DM. | Severe cardiomyopathy symptoms, skeletal muscle wasting, and smooth muscle weakening. | Lack of non-muscle-like symptoms. |

| HSALR | High levels of skeletal muscle expression of untranslated CUG repeats (≈250) in an unrelated mRNA. | The effect of CUG repeats in RNA and nuclear foci can be studied. | Interaction with transcription factors may be different from conventional DM. | High lethality in early developmental stages, myotonic discharges in young animals, myopaty in later stages. | Lack of muscle wasting and other neurological effects; the NMJ cannot be studied in depth. |

| DMSXL | Expanded DMPK transcript expression with different repeat sizes in various mouse tissues driven by cis-regulated human DM1 locus fragment. | Accumulation of ribonuclear foci and abnormal splicing patterns in multiple tissues in homozygous DM300. | Possible dose-dependent RNA toxicity. Time-consuming and costly mouse breeding. The correlation of copy number and phenotype is hard to quantify. | Skeletal muscle, cardiac and CNS symptoms such as myotonia, progressive muscle weakness, age-dependent glucose intolerance. | Relatively lower expression levels of the CUG-containing transcripts compared to other mouse model systems that lead to milder symptoms. |

| EpA960 | Cre-loxP system induced tissue-specific expression of DMPK exon 15 with large iterrupted CTG repeats. | Transcripts foci accumulation, MBNL1 sequestration, CELF1 upregulation, and the return of embryonic splicing patterns. | Due to tissue specificity, the complex multisystem symptoms of DM are hard to model but with leaky EpA960 transgene expression is manageable. | In cardiac tissue severe histopathological, functional and electrophysiological changes. In skeletal muscle, the Cre-loxP system induced myotonia and muscle weakness with progressive status. |

Due to tissue specificity, the complex multisystem symptoms of DM are hard to model. |

| GFP-DMPK-(CTG)X | Expression of the DMPK 3′UTR with different repeat sizes. | The extent of RNA toxicity shows CUG-triplet repeat dose effect on myogenesis in overexpressing model of DMPK 3′UTR, which can be compared in distinct repeat expansions. | The expression rate and the length of CUG repeat can affect the pathomechanism of DM differently. | In higher repeat numbers, the DM phenotype was present, and increased CUG expansion amplified the symptoms. | With small repeat numbers, the model failed to produce skeletal muscle atrophy, due to premature death caused by severe cardiac damage. |

| Mouse line to model abnormal splicing regulators connecting DM | Modeling MBNL sequestration by KO or propagating alternate splicing patterns by overexpressing CELF. | Simulation of downstream changes of DM by knocking out MBNL or overexpressing CELF. | The interactions of the protein family MBNL show a combinatorial loss-of-function nature and with the different expression levels of CELF, the system may show high variability. | Typical DM symptoms in various tissues: cataracts, motivation deficits and apathy, cardiac conduction defects. | Muscle weakness or muscle waisting was not detected. Histological, functional, and molecular changes were based on the rate of CELF upregulation. |

| DSMD-Q KO | Loss of function variants (frameshift, insertion, or deletion) induced by CRISPR-Cas9 to Dmpk, Six5, Mbnl1 and Dmwd genes. | Combines the three approaches of DM1: the haploinsufficiency model, the RNA toxicity model, and the chromatin structure malformation model. | Off-target problems of the CRISPR-Cas9 method dismissed by whole genom sequencing. | Conventional DM1 symptom: skeletal muscle wasting and weakness with correlating histopathology; heart problems; endocrine disorders; pathological changes in the digestive tract and neurological impairment caused by satellite cell malfunction. | Can simulate the characteristics of DM1 but not suitable for DM2. |

| Mouse lines to model downstream components of DM: Cav1.1e CLCN1 BIN1 Insulin receptor |

Alternative splicing variants of ion channels and/or receptors lead to the expression of embryonic form of channels and/or mutated receptors through development. | The effect of ion channels and/or metabolic pathway receptor misplicing can be studied separately from other genetical changes. | The genetic background vastly different from the conventional DM model lines such as RNA toxicity or haploinsufficieny approaches. | Can be used to distinguish the role of downstream components of DM pathomechanism. | CaV1.1 mainly affects intracellular calcium homeostatis such as mitochondria but not linked closely to other aspects of DM. CLCN1 mainly affects the conductive properties of excitable cells. |

2.3. Facioscapulohumeral Dystrophy

Facioscapulohumeral dystrophy (FSHD) also known as Landouzy–Dejerine syndrome is the 3rd most common autosomal dominant form of muscular dystrophy after DMD and DM. Its prevalence is 1:8500 to 15,000, and males are more often symptomatic compared to females [103]. The disease tends to progress slowly with periods of rapid deterioration, and it affects the face, shoulder blades, and upper arms muscles, leading to difficulty chewing or swallowing and slanted shoulders. Currently, there is no cure for FSHD, as no pharmaceuticals have proven effective for alleviating the disease course. Prognosis is variable, but most people with the disease have a normal lifespan.

The FSHD is a very complex disease with primate-specific genetic and epigenetic components. It is caused by the epigenetic de-repression of the double homebox protein 4 (DUX4) retrogene on chromosome 4, in the 4q35 region that leads to a gain-of-function disease [104]. DUX4 is expressed in early human development, while in mature tissues, it is suppressed. In FSHD, DUX4 is inadequately turned off, which can be due to several different mutations. The mutation termed “D4Z4 contraction” defines the FSHD type 1 (FSHD1), making up 95% of all FSHD cases, whereas the disease caused by other mutations is classified as FSHD2 or contraction independent.

There are a few FSHD1 mouse models available for preclinical efficiency testing prior to human clinical trials, but due to the unusual nature of the disease locus, these models will not recapitulate accurately the genetic and pathophysiological spectrum of the human condition, and overall, these models remain sub-optimal in assessing therapeutic efficacy (Table 3). The most significant hurdle that is impossible to overcome is that the D4Z4 macrosatellite encoding the toxic DUX4 retrogene is specific to primates, which impedes the possibility of working with a natural model of the disease [105]. Several xenograft models were developed in which skeletal muscle tissue from FSHD patients or muscle precursor cells were transplanted into the mouse muscle (see Table 3). There are currently no mouse models for FSHD2.

Table 3. Mouse models of facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy.

| Model System | Genetic Changes in the Mouse Model/Mutation(s) | Genetic Similarities/Genetic Background | Likeliness of Phenotype and Symptoms | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Advantage | Disadvantage | Advantage | Disadvantage | ||

| AAV6-DUX4 | TA injection of AAV6-DUX4 in 6–8-week-old mice. | On the C57BL/6 background. | Degenerating myofibers and infiltrating mononuclear cells. DUX4-induced cell death via p53-dependent pathway. |

Minor degeneration, increased central nuclei. Signs of apoptosis. |

|

| D4Z4-2.5 D4Z4-12.5 |

Transgenic insertion of two and a half copies of D4Z4 from the permissive haplotype of a pathogenic allele. Transgenic insertion of twelve and a half copies of D4Z4 from the permissive haplotype of a pathogenic allele. |

On the C57BL/6NJ background. Body-wide expression of the DUX-4 transcript in all tissues. |

Keratitis leading to blindness. DUX4 transcript detected in myoblasts and myotubes. DUX4 transcript was NOT detected in tibialis anterior and pectoralis muscles. |

No muscle weakness or abnormal morphology. | Satellite-cell derived myoblasts with DUX4 positive nuclei fail to fuse and form myotubes. Minor regeneration defect upon cardiotoxin injury. |

| iDUX-2.7 iDUX4pA |

Doxycycline-inducible DUX4 transgene on the X-chromosome. | On C57BL/6J background. | Abnormal embryogenesis, mostly lethal. Surviving males lived ‹ 2 months. | Weaker grip strength. Smaller muscles, impaired function, reduced specific force. |

Impaired myogenic regeneration. The activation of the downstream targets of DUX4 in mice differs from that in humans. Smaller and fewer myofibers, but not dystrophic. TA was least affected. |

| Xenograft | Human muscle engraftment into immunodeficient mice. | “Humanized” mouse model. | FSHD biomarker profile maintained in xenograft. | ||

| FRG1 | Transgenic insertion of FRG1 driven by a human skeletal α-actin promoter. | Spinal curvature correlated with the level of FRG1 expression. Dystrophic features. |

Fiber size variability, necrosis, centralized nuclei. Excess collagen, selective muscle atrophy, reduced exercise tolerance. | Abberant alternative splicing of specific pre-mRNAs. | |

| Fat1 | Knockout of Fat1. | Regionalized muscle and non-muscle abnormalities. | Retinal vasculopathy, abnormal inner ear patterning. Abnormal embryogenesis. |

Muscle weakness of the face and scapulohumeral region. | Altered myoblast migration polarity. |

| Pitx1 | Transgenic overexpression of Pitx1 induced in the absence of doxycycline. | Myofiber atrophy, necrotic and centrally nucleated fibers, inflamatory infiltration. | Polyadenylated DUX4 mRNA expressed at higher level in FSHD muscle. | Asymmetric muscle weakness in the face and shoulders that gradually progresses into the trunk and leg muscles. Evidence of endomysial inflamation. |

Retinal vasculopathy hearing loss. |

| TIC-DUX4 FLExDUX4 |

Tamoxifen inducible Cre-DUX4 | Reproductively viable. | No functional deficit of diaphragm muscles. Progressive pathology. Mild alopecia. Females more affected. |

AAV-mediated follistatin gene therapy improved muscle mass and strength. No extramuscular deficits. | Tamoxifen dose-dependent skeletal muscle pathology. Limited skeletal muscle pathology. |

References

- Hoffman, E.P.; Brown, R.H.; Kunkel, L.M. Dystrophin: The protein product of the duchenne muscular dystrophy locus. Cell 1987, 51, 919–928, doi:10.1016/0092-8674(87)90579-4.

- Ahn, A.H.; Kunkel, L.M. The structural and functional diversity of dystrophin. Nat. Genet. 1993, 3, 283–291, doi:10.1038/ng0493-283.

- Emery, A.E.H.; Muntoni, F. Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Hum. Genet. 2004, 115, 529–529, doi:10.1007/s00439-004-1189-4.

- Ryder, S.; Leadley, R.M.; Armstrong, N.; Westwood, M.; De Kock, S.; Butt, T.; Jain, M.; Kleijnen, J. The burden, epidemiology, costs and treatment for Duchenne muscular dystrophy: An evidence review. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2017, 12, 1–21, doi:10.1186/s13023-017-0631-3.

- Moat, S.J.; Bradley, D.M.; Salmon, R.; Clarke, A.; Hartley, L. Newborn bloodspot screening for Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy: 21 years experience in Wales (UK). Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 2013, 21, 1049–1053, doi:10.1038/ejhg.2012.301.

- Romitti, P.A.; Zhu, Y.; Puzhankara, S.; James, K.A.; Nabukera, S.K.; Zamba, G.K.D.; Ciafaloni, E.; Cunniff, C.; Druschel, C.M.; Mathews, K.D.; et al. Prevalence of Duchenne and Becker Muscular Dystrophies in the United States. Pediatrics 2015, 135, 513–521, doi:10.1542/peds.2014-2044.Prevalence.

- Gissel, H. The role of Ca2+ in muscle cell damage. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2005, 1066, 166–180, doi:10.1196/annals.1363.013.

- Klingler, W.; Jurkat-Rott, K.; Lehmann-Horn, F.; Schleip, R. The role of fibrosis in Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Acta Myol. 2012, 31, 184–195.

- Wallace, G.Q.; McNally, E.M. Mechanisms of muscle degeneration, regeneration, and repair in the muscular dystrophies. Annu. Rev. Physiol. 2009, 71, 37–57, doi:10.1146/annurev.physiol.010908.163216.

- Grounds, M.D.; Radley, H.G.; Lynch, G.S.; Nagaraju, K.; De Luca, A. Towards developing standard operating procedures for pre-clinical testing in the mdx mouse model of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Neurobiol. Dis. 2008, 31, 1–19, doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2008.03.008.

- Stedman, H.H.; Sweeney, H.L.; Shrager, J.B.; Maguire, H.C.; Panettieri, R.A.; Petrof, B.; Narusawa, M.; Leferovich, J.M.; Sladky, J.T.; Kelly, A.M. The mdx mouse diaphragm reproduces the degenerative changes of Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nature 1991, 352, 536–539.

- Beggs, A.H.; Hoffman, E.P.; Snyder, J.R.; Arahata, K.; Specht, L.; Shapiro, F.; Angelini, C.; Sugita, H.; Kunkel, L.M. Exploring the molecular basis for variability among patients with Becker muscular dystrophy: Dystrophin gene and protein studies. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1991, 49, 54–67.

- Deburgrave, N.; Daoud, F.; Llense, S.; Barbot, J.C.; Récan, D.; Peccate, C.; Burghes, A.H.M.; Béroud, C.; Garcia, L.; Kaplan, J.-C.; et al. Protein- and mRNA-Based Phenotype–Genotype Correlations in DMD/BMD With Point Mutations and Molecular Basis for BMD With Nonsense and Frameshift Mutations in the DMD Gene. Hum Mutat. 2007, 28, 183–195, doi:10.1002/humu.

- McGreevy, J.W.; Hakim, C.H.; McIntosh, M.A.; Duan, D. Animal models of Duchenne muscular dystrophy: From basic mechanisms to gene therapy. DMM Dis. Model. Mech. 2015, 8, 195–213, doi:10.1242/dmm.018424.

- Bulfield, G.; Siller, W.G.; Wight, P.A.L.; Moore, K.J. X chromosome-linked muscular dystrophy (mdx) in the mouse. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1984, 81, 1189–1192, doi:10.1073/pnas.81.4.1189.

- Krivov, L.I.; Stenina, M.A.; Yarygin, V.N.; Polyakov, A. V.; Savchuk, V.I.; Obrubov, S.A.; Komarova, N. V. A new Genetic variant of MDX mice: Study of the phenotype. Bull. Exp. Biol. Med. 2009, 147, 625–629, doi:10.1007/s10517-009-0564-5.

- Schmidt, W.M.; Uddin, M.H.; Dysek, S.; Moser-Thier, K.; Pirker, C.; Höger, H.; Ambros, I.M.; Ambros, P.F.; Berger, W.; Bittner, R.E. DNA damage, somatic aneuploidy, and malignant sarcoma susceptibility in muscular dystrophies. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, 1–17, doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1002042.

- Fukada, S.I.; Morikawa, D.; Yamamoto, Y.; Yoshida, T.; Sumie, N.; Yamaguchi, M.; Ito, T.; Miyagoe-Suzuki, Y.; Takeda, S.; Tsujikawa, K.; et al. Genetic background affects properties of satellite cells and mdx phenotypes. Am. J. Pathol. 2010, 176, 2414–2424, doi:10.2353/ajpath.2010.090887.

- Wasala, N.B.; Zhang, K.; Wasala, L.P.; Hakim, C.H.; Duan, D. The FVB Background Does Not Dramatically Alter the Dystrophic Phenotype of Mdx Mice. PloS Curr. 2015, 7, 1–17.

- Chapman, V.M.; Miller, D.R.; Armstrong, D.; Caskey, C.T. Recovery of induced mutations for X chromosome-linked muscular dystrophy in mice. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1989, 86, 1292–1296, doi:10.1073/pnas.86.4.1292.

- Aigner, B.; Rathkolb, B.; Klaften, M.; Sedlmeier, R.; Klempt, M.; Wagner, S.; Michel, D.; Mayer, U.; Klopstock, T.; Hrabé De Angelis, M.; et al. Generation of N-ethyl-N-nitrosourea-induced mouse mutants with deviations in plasma enzyme activities as novel organ-specific disease models. Exp. Physiol. 2009, 94, 412–421, doi:10.1113/expphysiol.2008.045864.

- Araki, E.; Nakamura, K.; Nakao, K.; Kameya, S.; Kobayashi, O.; Nonaka, I.; Kobayashi, T.; Katsuki, M. Targeted disruption of exon 52 in the mouse dystrophin gene induced muscle degeneration similar to that observed in duchenne muscular dystrophy. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1997, 238, 492–497, doi:10.1006/bbrc.1997.7328.

- Wertz, K.; Füchtbauer, E.M. Dmd(mdx-βgeo): A new allele for the mouse dystrophin gene. Dev. Dyn. 1998, 212, 229–241, doi:10.1002/(SICI)1097-0177(199806)212:2<229::AID-AJA7>3.0.CO;2-J.

- Kudoh, H.; Ikeda, H.; Kakitani, M.; Ueda, A.; Hayasaka, M.; Tomizuka, K.; Hanaoka, K. A new model mouse for Duchenne muscular dystrophy produced by 2.4 Mb deletion of dystrophin gene using Cre-loxP recombination system. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2005, 328, 507–516, doi:10.1016/j.bbrc.2004.12.191.

- Sarig, R.; Mezger-Lallemand, V.; Gitelman, I.; Davis, C.; Fuchs, O.; Yaffe, D.; Nudel, U. Targeted inactivation of Dp71, the major non-muscle product of the DMD gene: Differential activity of the Dp71 promoter during development. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999, 8, 1–10, doi:10.1093/hmg/8.1.1.

- Fort, P.E.; Darche, M.; Sahel, J.A.; Rendon, A.; Tadayoni, R. Lack of dystrophin protein Dp71 results in progressive cataract formation due to loss of fiber cell organization. Mol. Vis. 2014, 20, 1480–1490.

- Wein, N.; Vulin, A.; Falzarano, M.S.; Szigyarto, C.A.K.; Maiti, B.; Findlay, A.; Heller, K.N.; Uhlén, M.; Bakthavachalu, B.; Messina, S.; et al. Translation from a DMD exon 5 IRES results in a functional dystrophin isoform that attenuates dystrophinopathy in humans and mice. Nat. Med. 2014, 20, 992–1000, doi:10.1038/nm.3628.

- Arpke, R.W.; Darabi, R.; Mader, T.L.; Zhang, Y.; Toyama, A.; Lonetree, C.L.; Nash, N.; Lowe, D.A.; Perlingeiro, R.C.R.; Kyba, M. A new immuno-, dystrophin-deficient model, the NSG-mdx4Cv mouse, provides evidence for functional improvement following allogeneic satellite cell transplantation. Stem Cells 2013, 31, 1611–1620, doi:10.1002/stem.1402.

- Bencze, M.; Negroni, E.; Vallese, D.; Yacoubyoussef, H.; Chaouch, S.; Wolff, A.; Aamiri, A.; Di Santo, J.P.; Chazaud, B.; Butler-Browne, G.; et al. Proinflammatory macrophages enhance the regenerative capacity of human myoblasts by modifying their kinetics of proliferation and differentiation. Mol. Ther. 2012, 20, 2168–2179, doi:10.1038/mt.2012.189.

- Vallese, D.; Negroni, E.; Duguez, S.; Ferry, A.; Trollet, C.; Aamiri, A.; Vosshenrich, C.A.; Füchtbauer, E.M.; Di Santo, J.P.; Vitiello, L.; et al. The Rag2 - Il2rb - Dmd - Mouse: A novel dystrophic and immunodeficient model to assess innovating therapeutic strategies for muscular dystrophies. Mol. Ther. 2013, 21, 1950–1957, doi:10.1038/mt.2013.186.

- Farini, A.; Meregalli, M.; Belicchi, M.; Battistelli, M.; Parolini, D.; D’Antona, G.; Gavina, M.; Ottoboni, L.; Constantin, G.; Bottinelli, R.; et al. T and B lymphocyte depletion has a marked effect on the fibrosis of dystrophic skeletal muscles in the scid/mdx mouse. J. Pathol. 2007, 213, 229–238, doi:10.1002/path.

- Walsh, S.; Nygren, J.; Pontén, A.; Jovinge, S. Myogenic reprogramming of bone marrow derived cells in a W41Dmdmdx deficient mouse model. PLoS One 2011, 6, 1–5, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0027500.

- Rooney, J.E.; Welser, J. V.; Dechert, M.A.; Flintoff-Dye, N.L.; Kaufman, S.J.; Burkin, D.J. Severe muscular dystrophy in mice that lack dystrophin and α7 integrin. J. Cell Sci. 2006, 119, 2185–2195, doi:10.1242/jcs.02952.

- Guo, C.; Willem, M.; Werner, A.; Raivich, G.; Emerson, M.; Neyses, L.; Mayer, U. Absence of α7 integrin in dystrophin-deficient mice causes a myopathy similar to Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2006, 15, 989–998, doi:10.1093/hmg/ddl018.

- Grady, R.M.; Teng, H.; Nichol, M.C.; Cunningham, J.C.; Wilkinson, R.S.; Sanest, J.R. Skeletal and cardiac myopathies in mice lacking utrophin and dystrophin: A model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell 1997, 90, 729–738, doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80533-4.

- Susman, R.D.; Quijano-Roy, S.; Yang, N.; Webster, R.; Clarke, N.F.; Dowling, J.; Kennerson, M.; Nicholson, G.; Biancalana, V.; Ilkovski, B.; et al. Expanding the clinical, pathological and MRI phenotype of DNM2-related centronuclear myopathy. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2010, 20, 229–237, doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2010.02.016.

- Li, D.; Long, C.; Yue, Y.; Duan, D. Sub-physiological sarcoglycan expression contributes to compensatory muscle protection in mdx mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2009, 18, 1209–1220, doi:10.1093/hmg/ddp015.

- Banks, G.B.; Combs, A.C.; Odom, G.L.; Bloch, R.J.; Chamberlain, J.S. Muscle Structure Influences Utrophin Expression in mdx Mice. PLoS Genet. 2014, 10, 1–16, doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004431.

- Martins, P.C.M.; Ayub-Guerrieri, D.; Martins-Bach, A.B.; Onofre-Oliveira, P.; Malheiros, J.M.; Tannus, A.; De Sousa, P.L.; Carlier, P.G.; Vainzof, M. Dmdmdx/Largemyd: a new mouse model of neuromuscular diseases useful for studying physiopathological mechanisms and testing therapies. DMM Dis. Model. Mech. 2013, 6, 1167–1174, doi:10.1242/dmm.011700.

- Nishimura, D.; Sakai, H.; Sato, T.; Sato, F.; Nishimura, S.; Toyama-Sorimachi, N.; Bartsch, J.W.; Sehara-Fujisawa, A. Roles of ADAM8 in elimination of injured muscle fibers prior to skeletal muscle regeneration. Mech. Dev. 2015, 135, 58–67, doi:10.1016/j.mod.2014.12.001.

- Han, R.; Rader, E.P.; Levy, J.R.; Bansal, D.; Campbell, K.P. Dystrophin deficiency exacerbates skeletal muscle pathology in dysferlin-null mice. Skelet. Muscle 2011, 1, 1–11, doi:10.1186/2044-5040-1-35.

- Hosur, V.; Kavirayani, A.; Riefler, J.; Carney, L.M.B.; Lyons, B.; Gott, B.; Cox, G.A.; Shultz, L.D. Dystrophin and dysferlin double mutant mice: A novel model for rhabdomyosarcoma. Cancer Genet. 2012, 205, 232–241, doi:10.1016/j.cancergen.2012.03.005.

- Nitahara-Kasahara, Y.; Hayashita-Kinoh, H.; Chiyo, T.; Nishiyama, A.; Okada, H.; Takeda, S.; Okada, T. Dystrophic mdx mice develop severe cardiac and respiratory dysfunction following genetic ablation of the anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2014, 23, 3990–4000, doi:10.1093/hmg/ddu113.

- Sacco, A.; Mourkioti, F.; Tran, R.; Choi, J.; Llewellyn, M.; Kraft, P.; Shkreli, M.; Delp, S.; Pomerantz, J.H.; Artandi, S.E.; et al. Short telemeres and stem cell exhaustion model in mdx mice. Cell 2010, 143, 1059–1071, doi:10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.039.Short.

- Megeney, L.A.; Kablar, B.; Garrett, K.; Anderson, J.E.; Rudnicki, M.A. MyoD is required for myogenic stem cell function in adult skeletal muscle. Genes Dev. 1996, 10, 1173–1183, doi:10.1101/gad.10.10.1173.

- Deconinck, A.E.; Rafael, J.A.; Skinner, J.A.; Brown, S.C.; Potter, A.C.; Metzinger, L.; Watt, D.J.; Dickson, J.G.; Tinsley, J.M.; Davies, K.E. Utrophin-dystrophin-deficient mice as a model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Cell 1997, 90, 717–727, doi:10.1016/S0092-8674(00)80532-2.

- Ardite, E.; Perdiguero, E.; Vidal, B.; Gutarra, S.; Serrano, A.L.; Muñoz-Cánoves, P. PAI-1-regulated miR-21 defines a novel age-associated fibrogenic pathway in muscular dystrophy. J. Cell Biol. 2012, 196, 163–175, doi:10.1083/jcb.201105013.

- Cox, G.A.; Cole, N.M.; Matsumura, K.; Phelps, S.F.; Hauschka, S.D.; Campbell, K.P.; Faulkner, J.A.; Chamberlain, J.S. Overexpression of dystrophin in transgenic mdx mice eliminates dystrophic symptoms without toxicity. Nature 1993, 364, 725–729, doi:10.1038/364725a0.

- Phelps, S.F.; Hauser, M.A.; Cole, N.M.; Rafael, J.A.; Hinkle, R.T.; Faulkner, J.A.; Chamberlain, J.S. Expression of full-length and truncated dystrophin mini-genes in transgenic mdx mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1995, 4, 1251–1258.

- Dunckley, M.G.; Wells, D.J.; Walsh, F.S.; Dickson, G. Direct retroviral-mediated transfer of a dystrophin minigene into mdx mouse muscle in vivo. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1993, 2, 717–723, doi:10.1093/hmg/2.6.717.

- Cox, G.A.; Sunada, Y.; Campbell, K.P.; Chamberlain, J.S. Dp71 can restore the dystrophin-associated glycoprotein complex in muscle but fails to prevent dystrophy. Nat. Genet. 1994, 8, 333–339, doi:10.1038/ng1294-333.

- Greenberg, D.S.; Sunada, Y.; Campbell, K.P.; Yaffe, D.; Nudel, U. Exogenous Dp71 restores the levels of dystrophin associated proteins but does not alleviate muscle damage in mdx mice. Nat. Genet. 1994, 8, 340–344.

- Judge, L.M.; Arnett, A.L.H.; Banks, G.B.; Chamberlain, J.S. Expression of the dystrophin isoform Dp116 preserves functional muscle mass and extends lifespan without preventing dystrophy in severely dystrophic mice. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2011, 20, 4978–4990, doi:10.1093/hmg/ddr433.

- Judge, L.M.; Haraguchi, M.; Chamberlain, J.S. Dissecting the signalling and mechanical functions of the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex. J. Cell Sci. 2006, 119, 1537–1546, doi:10.1242/jcs.02857.

- Warner, L.E.; DelloRusso, C.T.; Crawford, R.W.; Rybakova, I.N.; Patel, J.R.; Ervasti, J.M.; Chamberlain, J.S. Expression of Dp260 in muscle tethers the actin cytoskeleton to the dystrophin-glycoprotein complex and partially prevents dystrophy. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2002, 11, 1095–1105, doi:10.1093/hmg/11.9.1095.

- Gaedigk, R.; Law, D.J.; Fitzgerald-Gustafson, K.M.; McNulty, S.G.; Nsumu, N.N.; Modrcin, A.C.; Rinaldi, R.J.; Pinson, D.; Fowler, S.C.; Bilgen, M.; et al. Improvement in survival and muscle function in an mdx/utrn-/- double mutant mouse using a human retinal dystrophin transgene. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2006, 16, 192–203, doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2005.12.007.

- Charlet-B, N.; Savkur, R.S.; Singh, G.; Philips, A. V; Grice, E.A.; Cooper, T.A. Loss of the Muscle-Specific Chloride Channel in Type 1 Myotonic Dystrophy Due to Misregulated Alternative Splicing several lines of evidence indicate that a gain of function for RNA CUG)n. Mol. Cell 2002, 10, 45–53.

- Hakim, C.H.; Duan, D. Truncated dystrophins reduce muscle stiffness in the extensor digitorum longus muscle of mdx mice. J. Appl. Physiol. 2013, 114, 482–489, doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00866.2012.

- Wang, B.; Li, J.; Fu, F.H.; Chen, C.; Zhu, X.; Zhou, L.; Jiang, X.; Xiao, X. Construction and analysis of compact muscle-specific promoters for AAV vectors. Gene Ther. 2008, 15, 1489–1499, doi:10.1038/gt.2008.104.

- Ferrer, A.; Foster, H.; Wells, K.E.; Dickson, G.; Wells, D.J. Long-term expression of full-length human dystrophin in transgenic mdx mice expressing internally deleted human dystrophins. Gene Ther. 2004, 11, 884–893, doi:10.1038/sj.gt.3302242.

- Tinsley, J.; Deconinck, N.; Fisher, R.; Kahn, D.; Phelps, S.; Gillis, J.M.; Davies, K. Expression of full-length utrophin prevents muscular dystrophy in mdx mice. Nat. Med. 1998, 4, 1441–1444, doi:10.1038/4033.

- Li, D.; Bareja, A.; Judge, L.; Yue, Y.; Lai, Y.; Fairclough, R.; Davies, K.E.; Chamberlain, J.S.; Duan, D. Sarcolemmal nNOS anchoring reveals a qualitative difference between dystrophin and utrophin. J. Cell Sci. 2010, 123, 2008–2013, doi:10.1242/jcs.064808.

- Gawlik, K.I.; Oliveira, B.M.; Durbeej, M. Transgenic expression of laminin α1 chain does not prevent muscle disease in the mdx mouse model for Duchenne muscular dystrophy. Am. J. Pathol. 2011, 178, 1728–1737, doi:10.1016/j.ajpath.2010.12.030.

- Moens, P.; Baatsen, P.H.W.W.; Maréchal, G. Increased susceptibility of EDL muscles from mdx mice to damage induced by contractions with stretch. J. Muscle Res. Cell Motil. 1993, 14, 446–451, doi:10.1007/BF00121296.

- Fong, P.; Turner, P.; Denetclaw, W.; Steinhardt, R. Increased activity of calcium leak channels in myotubes of Duchenne human and mdx mouse origin. Science (80-. ). 1990, 250, 673–676.

- Turner, P.R.; Schultz, R.; Ganguly, B.; Steinhardt, R.A. Proteolysis results in altered leak channel kinetics and elevated free calcium in mdx muscle. J. Membr. Biol. 1993, 133, 243–251, doi:10.1007/BF00232023.

- Vandebrouck, C.; Constantin, B.; Raymond, G.; Cognard, C.; Duport, G. Normal calcium homeostasis in dystrophin-expressing facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy myotubes. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2002, 12, 266–272, doi:10.1016/S0960-8966(01)00279-6.

- Avila, G.; O’Brien, J.J.; Dirksen, R.T. Excitation - Contraction uncoupling by a human central core disease mutation in the ryanodine receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2001, 98, 4215–4220, doi:10.1073/pnas.071048198.

- Bostick, B.; Yue, Y.; Long, C.; Duan, D. Prevention of dystrophin-deficient cardiomyopathy in twenty-one-month-old carrier mice by mosaic dystrophin expression or complementary dystrophin/utrophin expression. Circ. Res. 2008, 102, 121–130, doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.107.162982.

- Bostick, B.; Yue, Y.; Long, C.; Marschalk, N.; Fine, D.M.; Chen, J.; Duan, D. Cardiac expression of a mini-dystrophin that normalizes skeletal muscle force only partially restores heart function in aged Mdx mice. Mol. Ther. 2009, 17, 253–261, doi:10.1038/mt.2008.264.

- Hakim, C.H.; Grange, R.W.; Duan, D. The passive mechanical properties of the extensor digitorum longus muscle are compromised in 2-to 20-mo-old mdx mice. J. Appl. Physiol. 2011, 110, 1656–1663, doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.01425.2010.

- Lefaucheur, J.P.; Pastoret, C.; Sebille, A. Phenotype of dystrophinopathy in old MDX mice. Anat. Rec. 1995, 242, 70–76, doi:10.1002/ar.1092420109.

- Pastoret, C.; Sebille, A. Mdx Mice Show Progressive Weakness and Muscle Deterioration With Age. J. Neurol. Sci. 1995, 129, 97–105, doi:10.1016/0022-510X(94)00276-T.

- Im, W. Bin; Phelps, S.F.; Copen, E.H.; Adams, E.G.; Slightom, J.L.; Chamberlain, J.S. Differential expression of dystrophin isoforms in strains of mdx mice with different mutations. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1996, 5, 1149–1153, doi:10.1093/hmg/5.8.1149.

- Megeney, L.A.; Kablar, B.; Perry, R.L.S.; Ying, C.; May, L.; Rudnicki, M.A. Severe cardiomyopathy in mice lacking dystrophin and MyoD. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 1999, 96, 220–225, doi:10.1073/pnas.96.1.220.

- Mourkioti, F.; Kustan, J.; Kraft, P.; Day, J.W.; Zhao, M.-M.; Kost-Alimova, M.; Protopopov, A.; DePinho, R.A.; Bernstein, D.; Meeker, A.K.; et al. Role of Telomere Dysfunction in Cardiac Failure in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy. Nat Cell Biol 2013, 15, 895–904, doi:10.1038/ncb2790.Role.

- Matsumura, C.Y.; Taniguti, A.P.T.; Pertille, A.; Neto, H.S.; Marques, M.J. Stretch-activated calcium channel protein TRPC1 is correlated with the different degrees of the dystrophic phenotype in mdx mice. Am. J. Physiol. - Cell Physiol. 2011, 301, 1344–1350, doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00056.2011.

- Rafael-Fortney, J.A.; Chimanji, N.S.; Schill, K.E.; Martin, C.D.; Murray, J.D.; Ganguly, R.; Stangland, J.E.; Tran, T.; Xu, Y.; Canan, B.D.; et al. Early Treatment with Lisinopril and Spironolactone Preserves Cardiac and Skeletal Muscle in Duchenne Muscular Dystrophy Mice. Circulation 2011, 124, 582–588, doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.111.031716.Early.

- van Putten, M.; Kumar, D.; Hulsker, M.; Hoogaars, W.M.H.; Plomp, J.J.; van Opstal, A.; van Iterson, M.; Admiraal, P.; van Ommen, G.J.B.; ’t Hoen, P.A.C.; et al. Comparison of skeletal muscle pathology and motor function of dystrophin and utrophin deficient mouse strains. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2012, 22, 406–417, doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2011.10.011.

- Selsby, J.T.; Ross, J.W.; Nonneman, D.; Hollinger, K. Porcine models of muscular dystrophy. ILAR J. 2015, 56, 116–126, doi:10.1093/ilar/ilv015.

- Straub, V.; Murphy, A.; Udd, B. 229th ENMC international workshop: Limb girdle muscular dystrophies – Nomenclature and reformed classification Naarden, the Netherlands, 17–19 March 2017. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2018, 28, 702–710, doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2018.05.007.

- Hornsey, M.A.; Laval, S.H.; Barresi, R.; Lochmüller, H.; Bushby, K. Muscular dystrophy in dysferlin-deficient mouse models. Neuromuscul. Disord. 2013, 23, 377–387, doi:10.1016/j.nmd.2013.02.004.

- van Putten, M.; Lloyd, E.M.; de Greef, J.C.; Raz, V.; Willmann, R.; Grounds, M.D. Mouse models for muscular dystrophies: an overview. Dis. Model. Mech. 2020, 13, doi:10.1242/dmm.043562.

- Fu, Y.-H.; L.Friedman, D.; Richards, S.; Pearlman, J.A.; Gibbs, R.A.; Pizzuti, A.; Ashizawa, T.; Rerryman, M.B.; Scarlato, G.; Fenwick, R.G.; et al. Decreased expression of myotonin-protein kinase messenger RNA and protein in adult form of myotonic dystrophy. Science (80-. ). 1993, 260, 235–238.

- Jansen, G.; Groenen, P.J.T.A.; Bächner, D.; Jap, P.H.K.; Coerwinkel, M.; Oerlemans, F.; Van Den Broek, W.; Gohlsch, B.; Pette, D.; Plomp, J.J.; et al. Abnormal myotonic dystrophy protein kinase levels produce only mild myopathy in mice. Nat. Genet. 1996, 13, 316–324, doi:10.1038/ng0796-316.

- Alwazzan, M.; Newman, E.; Hamshere, M.G.; Brook, J.D. Myotonic dystrophy is associated with a reduced level of RNA from the DMWD allele adjacent to the expanded repeat. Hum. Mol. Genet. 1999, 8, 1491–1497, doi:10.1093/hmg/8.8.1491.

- Junghans, R.P.; Ebralidze, A.; Tiwari, B. Does (CUG)n repeat in DMPK mRNA “paint” chromosome 19 to suppress distant genes to create the diverse phenotype of myotonic dystrophy?: A new hypothesis of long-range cis autosomal inactivation. Neurogenetics 2001, 3, 59–67, doi:10.1007/s100480000103.

- Klesert, T.R.; Cho, D.H.; Clark, J.I.; Maylie, J.; Adelman, J.; Snider, L.; Yuen, E.C.; Soriano, P.; Tapscott, S.J. Mice deficient in Six5 develop cataracts: Implications for myotonic dystrophy. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 105–109, doi:10.1038/75490.

- Sarkar, P.S.; Appukuttan, B.; Han, J.; Ito, Y.; Ai, C.; Tsai, W.; Chai, Y.; Stout, J.T.; Reddy, S. Heterozygous loss of Six5 in mice is sufficient to cause ocular cataracts. Nat. Genet. 2000, 25, 110–114, doi:10.1038/75500.

- Mankodi, A.; Logigian, E.; Callahan, L.; McClain, C.; White, R.; Henderson, D.; Krym, M.; Thornton, C.A. Myotonic dystrophy in transgenic mice expressing an expanded CUG repeat. Science (80-. ). 2000, 289, 1769–1772, doi:10.1126/science.289.5485.1769.

- Ranum, L.P.W.; Rasmussen, P.F.; Benzow, K.A.; Koob, M.D.; Day, J.W. Genetic mapping of a second myotonic dystrophy locus. Nat. Genet. 1998, 19, 196–198, doi:10.1038/570.

- Liquori, C.L.; Ricker, K.; Moseley, M.L.; Jacobsen, J.F.; Kress, W.; Naylor, S.L.; Day, J.W.; Ranum, L.P.W. Myotonic dystrophy type 2 caused by a CCTG expansion in intron I of ZNF9. Science (80-. ). 2001, 293, 864–867, doi:10.1126/science.1062125.

- Timchenko, L.T.; Miller, J.W.; Timchenko, N.A.; Devore, D.R.; Datar, K. V.; Lin, L.; Roberts, R.; Thomas Caskey, C.; Swanson, M.S. Identification of a (CUG)(n) triplet repeat RNA-binding protein and its expression in myotonic dystrophy. Nucleic Acids Res. 1996, 24, 4407–4414, doi:10.1093/nar/24.22.4407.

- Philips, A. V.; Timchenko, L.T.; Cooper, T.A. Disruption of splicing regulated by a CUG-binding protein in myotonic dystrophy. Science (80-. ). 1998, 280, 737–741, doi:10.1126/science.280.5364.737.

- Miller, J.W.; Urbinati, C.R.; Teng-Umnuay, P.; Stenberg, M.G.; Byrne, B.J.; Thornton, C.A.; Swanson, M.S. Recruitment of human muscleblind proteins to (CUG)(n) expansions associated with myotonic dystrophy. EMBO J. 2000, 19, 4439–4448, doi:10.1093/emboj/19.17.4439.

- Kanadia, R.N.; Shin, J.; Yuan, Y.; Beattie, S.G.; Wheeler, T.M.; Thornton, C.A.; Swanson, M.S. Reversal of RNA missplicing and myotonia after muscleblind overexpression in a mouse poly(CUG) model for myotonic dystrophy. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2006, 103, 11748–11753, doi:10.1073/pnas.0604970103.

- Ward, A.J.; Rimer, M.; Killian, J.M.; Dowling, J.J.; Cooper, T.A. CUGBP1 overexpression in mouse skeletal muscle reproduces features of myotonic dystrophy type 1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010, 19, 3614–3622, doi:10.1093/hmg/ddq277.

- Koshelev, M.; Sarma, S.; Price, R.E.; Wehrens, X.H.T.; Cooper, T.A. Heart-specific overexpression of CUGBP1 reproduces functional and molecular abnormalities of myotonic dystrophy type 1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2010, 19, 1066–1075, doi:10.1093/hmg/ddp570.

- Mankodi, A.; Takahashi, M.P.; Jiang, H.; Beck, C.L.; Bowers, W.J.; Moxley, R.T.; Cannon, S.C.; Thornton, C.A. Expanded CUG repeats trigger aberrant splicing of ClC-1 chloride channel pre-mRNA and hyperexcitability of skeletal muscle in myotonic dystrophy. Mol. Cell 2002, 10, 35–44, doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00563-4.

- Fugier, C.; Klein, A.F.; Hammer, C.; Vassilopoulos, S.; Ivarsson, Y.; Toussaint, A.; Tosch, V.; Vignaud, A.; Ferry, A.; Messaddeq, N.; et al. Misregulated alternative splicing of BIN1 is associated with T tubule alterations and muscle weakness in myotonic dystrophy. Nat. Med. 2011, 17, 720–725, doi:10.1038/nm.2374.

- Kimura, T.; Nakamori, M.; Lueck, J.D.; Pouliquin, P.; Aoike, F.; Fujimura, H.; Dirksen, R.T.; Takahashi, M.P.; Dulhunty, A.F.; Sakoda, S. Altered mRNA splicing of the skeletal muscle ryanodine receptor and sarcoplasmic/endoplasmic reticulum Ca2+-ATPase in myotonic dystrophy type 1. Hum. Mol. Genet. 2005, 14, 2189–2200, doi:10.1093/hmg/ddi223.

- López-Martínez, A.; Soblechero-Martín, P.; De-la-Puente-Ovejero, L.; Nogales-Gadea, G.; Arechavala-Gomeza, V. An Overview of Alternative Splicing Defects Implicated in Myotonic Dystrophy Type I. Genes (Basel). 2020, 11, 1–27.

- Deenen, J.C.W.; Arnts, H.; Van Der Maarel, S.M.; Padberg, G.W.; Verschuuren, J.J.G.M.; Bakker, E.; Weinreich, S.S.; Verbeek, A.L.M.; Van Engelen, B.G.M. Population-based incidence and prevalence of facioscapulohumeral dystrophy. Neurology 2014, 83, 1056–1059, doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000000797.

- Gabriëls, J.; Beckers, M.C.; Ding, H.; De Vriese, A.; Plaisance, S.; Van Der Maarel, S.M.; Padberg, G.W.; Frants, R.R.; Hewitt, J.E.; Collen, D.; et al. Nucleotide sequence of the partially deleted D4Z4 locus in a patient with FSHD identifies a putative gene within each 3.3 kb element. Gene 1999, 236, 25–32, doi:10.1016/S0378-1119(99)00267-X.

- Lek, A.; Rahimov, F.; Jones, P.L.; Kunkel, L.M. Emerging preclinical animal models for FSHD. Trends Mol. Med. 2015, 21, 295–306, doi:10.1016/j.molmed.2015.02.011.