| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ho Manh Toan | + 2773 word(s) | 2773 | 2021-01-15 06:31:54 | | | |

| 2 | Ho Manh Toan | Meta information modification | 2773 | 2021-01-15 12:55:56 | | | | |

| 3 | Quan-Hoang Vuong | + 2 word(s) | 2775 | 2021-01-15 13:03:50 | | | | |

| 4 | Ho Manh Toan | Meta information modification | 2775 | 2021-01-15 18:45:28 | | | | |

| 5 | Hong Kong Nguyen | Meta information modification | 2775 | 2021-01-16 13:44:43 | | | | |

| 6 | Ho Manh Toan | + 15 word(s) | 2790 | 2021-07-13 07:00:49 | | | | |

| 7 | Ho Manh Toan | + 15 word(s) | 2790 | 2021-07-13 07:25:35 | | | | |

| 8 | Ho Manh Toan | + 15 word(s) | 2790 | 2021-07-13 07:33:10 | | | | |

| 9 | Ho Manh Toan | Meta information modification | 2790 | 2021-07-13 11:15:04 | | | | |

| 10 | Quan-Hoang Vuong | Meta information modification | 2790 | 2021-07-13 13:58:53 | | | | |

| 11 | Quan-Hoang Vuong | Meta information modification | 2790 | 2021-07-13 19:26:02 | | | | |

| 12 | Minh-Hoang Nguyen | -1 word(s) | 2789 | 2021-07-16 13:35:17 | | | | |

| 13 | Minh-Hoang Nguyen | + 6 word(s) | 2795 | 2021-07-18 19:50:46 | | | | |

| 14 | Minh-Hoang Nguyen | + 21 word(s) | 2816 | 2022-09-01 20:05:51 | | | | |

| 15 | Catherine Yang | Meta information modification | 2816 | 2022-09-02 03:06:27 | | |

Video Upload Options

This entry provides the conceptual development of “cultural additivity.” It reviews the three most relevant concepts namely syncretism, cultural hybridity, and creolization, and then makes a case for the usefulness of “cultural additivity” in explaining the adoption and rejection of emerging cultural values. The newly introduced concept utilizes a well-developed theory called mindsponge theory.

Introduction

The constant interactions among humans as well as between humans and the surrounding environment give rise to many phenomena to which cultural studies seek to decipher. Among the puzzles are why humans behave in certain ways, including ways that are completely contradictory to their existing belief systems. Are these behaviors the same or different across cultures? And how should we make sense of such cognitive dissonance from a cultural perspective?

Cultural anthropologists have long held that, although evolutionary biologists, neuroscientists, and behavioral scientists do offer insightful tools to better understand human behaviors, these approaches tend to lack explanatory power for neglecting the issue of culture and its role in shaping human behavior [1][2][3]. Inspired by and drawing from a voluminous literature on culture and human behaviors, this book introduces a new concept – “cultural additivity” – that supplants existing theories on the transmission, formation, transformation, and fusion of cultures. Prior to our studies on this concept [4][5], only one academic paper has mentioned the term, but no exploration was followed [6]. In our research, the concept, though in its infancy, provides a framework for debunking any mechanisms in which “people of a given culture are willing to incorporate into their culture the values and norms from other systems of beliefs that might or might not logically contradict with principles of their existing system of beliefs” [4].

In order to lay the groundwork for conceptualizing “cultural additivity,” this essay first revisits a number of relevant concepts such as syncretism, cultural hybridity, and creolization. These are indeed well-known terms depicting the combination and mixing of different traditions and values, be them religious, political, cultural, or practical. By drawing from this literature, the essay outlines several points that distinguish the concept of “cultural additivity” from the aforementioned concepts. On that basis, the next part delves into the definition and content of “cultural additivity” and, subsequently, the applicability of the term in cultural studies and beyond.

Revisiting: syncretism, cultural hybridity, and creolization

The fusion of different cultural values and phenomena takes place through vastly different modes, hence, the diverse set of terms aimed at capturing the process. The terms, while all denoting the mixing of distinctive elements vary in their historical roots, substance, connotations, and overall usage.

Historically speaking, creolization and syncretism appear to be the oldest with their original usage dated to the sixteenth century, with the former denoting the acclimatization of the Old World to the New World and the latter carrying heavy religious connotations. Nonetheless, as Stewart (2011) has noted, both terms can also be interpreted outside our understanding of them as some sort of mixture [7]. For syncretism, there can be cases in which people of different religions and cultures come to share similar practices and/or values merely through a gradual convergence, not syncretism or borrowing of such practices/values. Similarly, creolization does not necessarily require a genetic mixture for it can be the result of localization, acculturation, and even acquisition of cultural practices/values [7].

This is clearly not the case for cultural hybridity, which was first used in the latter half of the nineteenth century to denote the mixing of people of different races [8][9][10]. Hybridization, as such, inevitably implies a sort of complete fusion of distinctive racial and cultural values. Post-colonial scholars play an important role in reframing the term hybridity beyond the earlier historical fixation on racial mixing, colonial society, and immigrant communities. This is because scholars now uphold that culture is innately hybrid, no single culture has remained pure amid globalization [8].

Despite their distinctive historical backgrounds and usage contexts, all three terms present a fusion—to different degrees—of the original and the foreign (as in cultural hybridity), the old and the new (in creolization), and the core and the foreign (in syncretism). We see new, foreign, and peripheral beliefs, values, practices, and/or artifacts being added and crossed over with their existing, old, and core counterparts. For instance, for religious syncretism, which is characterized as a cultural process constitutive of the larger process of cultural diffusion, there can be a high or low level of fusion between the core missionary values and the indigenous religious values [11]. It is this kind of process that the term “cultural additivity” elaborates on, all the while staying detached from the heavy historical baggage of the extant terminologies. Table 1 recaps the main content of the three concepts in comparison with “cultural additivity” [4].

Table 1. A reproduced and updated summary of three concepts that are most relevant to “cultural additivity” (Vuong et al., 2018) [4].

|

|

Hybridity |

Creolization |

Syncretism |

Cultural additivity |

|

History |

Nineteenth century; |

Sixteenth century; Old World vs. New World; |

Sixteenth century; Reformation age; |

First used by Klug (1973) in the discussion on Judeo-Christian-Black views; still in the process of formalization; |

|

Context |

Post-colonialism; Globalization; Modernization; |

Linguistics studies; Displacement; Indigenization; |

Religious studies; Cultural dissonance; |

Cultural behavior and attitude; Wider applicability |

|

Content |

The original vs. the foreign; “pure” vs. “impure”; |

The new vs. the old; |

Core values vs. foreign values; Reconciliation reached for contradictions; |

Core values vs. additional values, including anti-values; Reconciliation not necessary; |

|

Result(s) |

Complete fusion; Heterogeneity; |

On-going transformation, mutual influence; |

Repression of one of the two religions; Complete fusion; Syncretic result; |

Open-ended hodgepodge; |

A question worth raising is, how do these concepts account for the complexity of contradictory values, beliefs, religions, etc. being mixed together? In a study of late imperial China’s worship of the Three Teachings of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism, Brook (1993) finds that syncretism is rare because the reconciliation or resolution of elements of distinct world views can hardly happen [12]. Thus, besides perfect fusion, what may ensue is: (i) one of the values being repressed, or (ii) both values getting syncretized with the foreign elements seen as critical or peripheral [13]. By comparison, the processes of hybridization and creolization often shift the attention away from the clashing of values, and instead toward a cultural creativity process in which new values and entities emerge [14][15][9]. As a result of the interactions between the indigenous culture and the foreign culture, Creole forms take on expressive, fluid, multivocal characteristics, and thereby, representing creativity at work [14]. This is particularly relevant when Creole encounters are asymmetrical or dominated by one or more cultures. It is through these encounters that contradictions or conflicts may arise, from which the creole social actors selectively accept and/or reject the newly-introduced elements of the other culture [14]. Similarly, under cultural hybridization, when one culture comes into contacts with another, such as in the context of immigration, colonization, or globalization, a process of creative engagements would take place, giving rise to hybrid cultural forms. In the encounters of the local culture with global forces, creative hybridization would emerge in the form of the locals constantly re-imagining identities through reciprocal cultural exchanges [16].

With that said, we move on to elaborate on where “cultural additivity” fits into this literature.

Conceptualization

Positioning

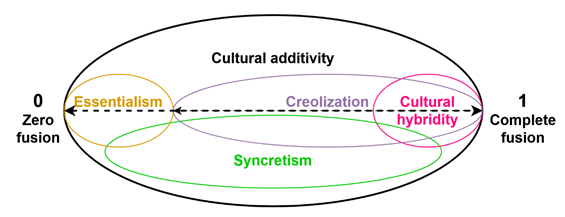

The literature shows that there are certain overlaps as well as distinct features in the three concepts of syncretism, cultural hybridity, and creolization. Figure 1 places these concepts on a visualized scale from 0 (zero fusion) to 1 (complete fusion), enabling a clearer positioning of each concept and their overlapping areas. As can be seen, the sphere for “cultural additivity” is envisioned to be the largest, covering the full spectrum from none to total fusion. Within this biggest sphere are the concepts discussed above, plus one addition. In particular, essentialism—a philosophy that holds every entity to have an underlying substance or true nature that cannot be mixed up with others—lies at the farthest left end as its meaning amounts to zero fusion. On the opposite right end lies cultural hybridity, a concept that often signifies a complete merge of two cultures. Somewhere in between are the spheres of creolization and syncretism. There is no overlapping area between essentialism and creolization because the latter inherently requires some minimum contact with and incorporation of additional values or beings. Syncretism is the closest concept to what we mean by “cultural additivity,” minus the religious undertone and usage, and thus, it overlaps with all the other three concepts. This understanding is in line with Grayson (1984)’s categorization of syncretism: high and low levels that reflect the changes in the core set of values following the interaction between indigenous religion and a missionary religion [11]. Notably, Grayson’s notion of “high syncretism,” or reverse syncretism, likely corresponds to the higher level of fusion, leaning toward the value of 1 in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Mapping of concepts relevant to “cultural additivity” on a scale of 0 (zero fusion) to 1 (complete fusion).

In mapping the concepts, we also note that one major weakness of the extant terminologies. In trying to explain encounters and mixture with new elements, these terms tend to place the new, the foreign, the peripheral in an antithetical position to the extant ones. While it certainly helps to break down the dichotomy between the core and the non-core, between the native and the foreign, between the new and the old, this approach may end up simplifying cultural behaviors, and worse, reinforcing the already dominant discourse of We versus Other in the study of cultural identities. This is the gap that the concept of “cultural additivity” fills. The measurement, though imprecise, is left open to interpretation and further development. Its focus is not on the pitting of ideas, values, beliefs, entities, or beings against one another, but rather is on understanding how additional elements, whatever they be, can be included in an existing system, including at both the individual and societal levels. This is the reason why the positioning of concepts places them along the line of no fusion and complete fusion, instead of our usual intuition of seeing the no-fusion as original or pure. Such terms only deepen our cognitive bias, and hence, are not helpful in making a new concept more accessible.

In other words, besides not being loaded historically, the concept of “cultural additivity” captures cultural phenomena in a broader sense, rather than the conventional binary approach. Core values still exist, but here the focus is on how these core values interact with additional values as a whole. As each layer of additional values is integrated into the core layer over time, they would become the new core values. The process of additivity can take place indefinitely so long as there is tolerance for adding something new, even if there may be contradictions.

Cultural additivity: a model

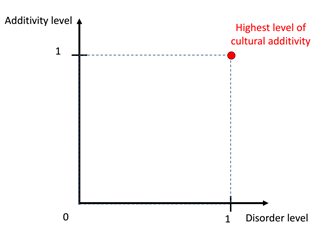

We introduce “cultural additivity” as a model aimed at explaining the phenomenon of society members processing new values, including anti-values. Here, the adding and integration of new values and/or new elements constitute what we call the “additivity level,” visualized as the vertical axis in Figure 2.

Figure 2. Preliminary conceptualization of “cultural additivity”

Specifically, Figure 2 envisions the concept of “cultural additivity” in a two-dimensional plane, with each axis scaled from minimum 0 to maximum 1 and corresponding to two components: the additivity level (the vertical axis) and the disorder level (the horizontal axis). The additivity level, characterized as the adding and integrating of new elements, is concerned with how creativity is at work. To study creativity within the additivity process, we suggest utilizing the mechanism of mindsponge, as developed by Vuong Quan Hoang [17] and Vuong Quan Hoang and Nancy K. Napier [18].

The disorder level, meanwhile, addresses the degree of novelty of the added values, beliefs, ideas, and/or artifacts, etc., as well as the presence of contradictions to existing ones. By Figure 2, when the disorder level reaches its max value of 1, and additivity still happens to completion – also the max value of 1, this would mark the highest level of cultural additivity. In other words, the concept of cultural additivity can be operationalized along with the 0 to 1 scale, with zero denoting its absence and one denoting the strongest presence.

While the two levels, developed in this preliminary form, are by no means the sole components to understand “cultural additivity,” they nonetheless present a more intuitive look into a nascent concept. Providing clarity for the model helps set it apart from the other relevant concepts as well as improve its applicability. At this early stage of conceptualization, details on the measurement of each level are not yet formalized and would need to be worked out in future studies.

Mindsponge: a learning and unlearning mechanism

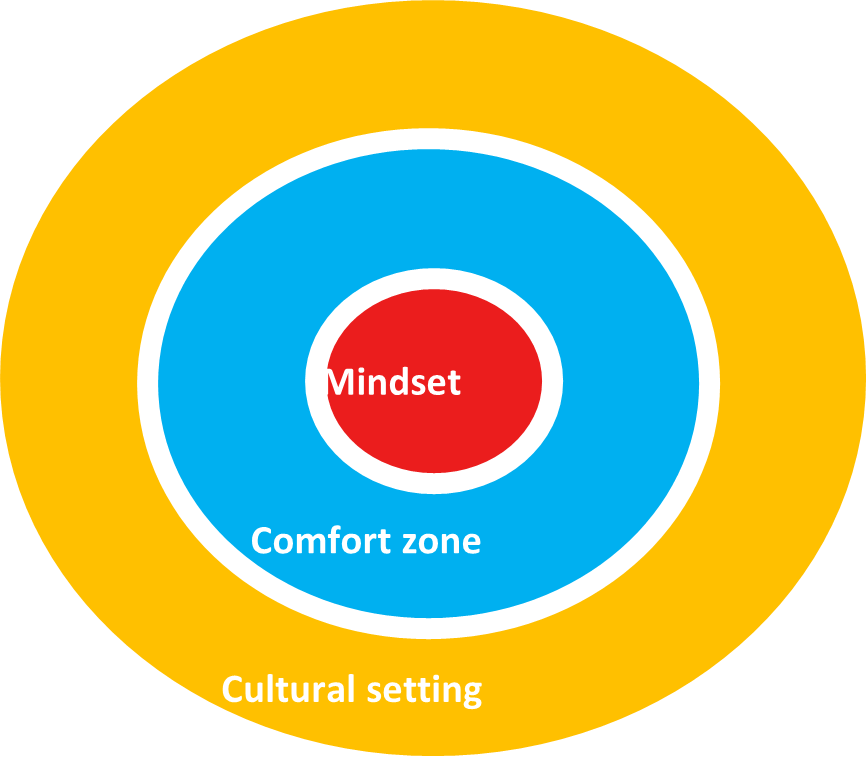

To understand the model of cultural additivity, it is necessary to explicate what the mechanism of mindsponge looks like. According to Vuong [17] and Vuong and Napier [18], mindsponge is defined as “a mechanism for explaining how an individual absorbs and integrates new cultural values into her/his own set of core values and the reverse of ejecting waning ones.” Figure 3 shows a simplified visualization of mindsponge, which comprises three parts: (i) the red circle at the core represents an individual’s mindset, (ii) the middle blue circle represents an individual’s comfort zone – where incoming information, e.g., new values and/or beliefs, is filtered, differentiated, integrated, or rejected, depending on the mindset’s existing core values, and (iii) the most outer yellow circle denotes the external environment, also known as the cultural and ideological setting in which mindsponge takes place.

Figure 3. A reproduced simplified diagram of mindsponge, based on Vuong and Napier [17].

Given that the mindsponge mechanism takes place at an individual level, we argue that the way individuals in a society learn and unlearn information, accept and reject values, altogether determine the level of cultural additivity of that society. In a way, there is a feedback loop between individual behaviors and societal behaviors, and hence, its culture. We hypothesize that in a society with a high level of cultural additivity, even as individuals have vastly different core values, these values are not entirely discarded but are kept in their comfort zone. By contrast, in a society with a low level of cultural additivity, differing and contradictory values are rejected right away, leaving only values that are compatible with the individuals’ core value system. In this sense, the level of cultural additivity of society is expected to fluctuate constantly, depending on the rate of information and value exchange as well as the kind of information and value being disseminated and promoted in that society. Recently, the mindsponge mechanism has been developed into mindsponge theory [19], and can be applied as an analytical method following the Bayesian Mindsponge Framework analytics [20][21].

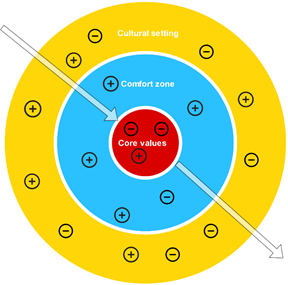

Figure 4 presents a visualization of how the mindsponge mechanism works in filtering values and anti-values, resulting in changes in both the core values of the individuals and the external cultural setting. The color scheme is similar to that of Figure 3 for coherence purposes. The plus (+) sign represents values that are in line with the core values (denoted by the nucleus red circle) while the minus (-) represents values that are antithetical to the core values. As new values emerge in an individual’s existing cultural setting and introduced to the individual, they would have to go through the individual’s comfort zone, which is a buffer area for processing and filtering values.

Figure 4. Mindsponge at work in the model of “cultural additivity”

Conclusion

This essay lays out the conceptual development for “cultural additivity,” drawing on insights from relevant concepts such as cultural hybridity, syncretism, and creolization. The new concept is distinct from the extant ones in three primary ways. First, given its novelty, it is removed from the loaded historicity associated with the other concepts. This allows the term “cultural additivity” to be used in a wider context, even outside the realm of cultural studies. Second, the concept focuses on explaining the addition and merging of values, including anti-values, and thus, diverges from the usual binary framing of original vs. foreign and of new vs. foreign in cultural studies. Third, unlike the other three concepts, “cultural additivity” presents a model with greater clarity and applicability, supported by the multi-filtering information mechanism of mindsponge. The mechanism is based on the understanding that cultural values, in general, are deeply rooted in our mindsets, surrounding which are values from other individuals and institutions [18][22].

In our model, societies can have different levels of cultural additivity: the higher this is, the more individuals in that societies appear to tolerate and accept emerging values; the lower the level of cultural additivity, the less willing society individuals are toward emerging values. As new values are introduced and arise on a daily basis across societies, the level of cultural additivity is likely to oscillate constantly on a continuum from 0 (no additivity) to 1 (highest additivity and disorder). These measurements will need to be formalized in detail in future studies. Currently, cultural additivity and its implications have been used widely by scientists around the world [23][24][25].

References

- Cronk L. (1999). That Complex Whole: Culture and the Evolution of Human Behavior. Westview Press.

- Keesing RM. (1974). Theories of Culture. Annual Review of Anthropology, 3, 73-97. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2949283

- Richerson PJ, Robert B. (2005). Not By Genes Alone: How Culture Transformed Human Evolution. University of Chicago Press.

- Vuong QH, et al. (2018). Cultural additivity: behavioural insights from the interaction of Confucianism, Buddhism and Taoism in folktales. Palgrave Communications, 4(1), 143.

- Vuong QH, et al. (2020). On how religions could accidentally incite lies and violence: folktales as a cultural transmitter. Palgrave Communications, 6(1), 82.

- Klug DP. (1973). The significance of the Judeo-Christian-Black concept of man and history in values education. Doctorate. Ohio State University, Columbus, OH. http://rave.ohiolink.edu/etdc/view?acc_num=osu1486744760982123

- Stewart C. (2011). Creolization, Hybridity, Syncretism, Mixture. Portuguese Studies, 27(1), 48-55. https://doi.org/10.5699/portstudies.27.1.0048

- Ackermann A. (2011). Cultural hybridity: between metaphor and empiricism. In P. W. Stockhammer (Ed.), Conceptualizing cultural hybridization: a transdisciplinary approach (pp. 5-25). Springer.

- Stockhammer PW. (2011). Questioning Hybridity. In P. W. Stockhammer (Ed.), Conceptualizing Cultural Hybridization: A Transdisciplinary Approach (pp. 1-13). Berlin Heidelberg, Heidelberg.

- Young R. (1995). Colonial desire: Hybridity in theory, culture, and race. Routledge.

- Grayson JH. (1984). Religious Syncretism in the Shilla Period: The Relationship between Esoteric Buddhism and Korean Primeval Religion. Asian Folklore Studies, 43(2), 185-198. https://doi.org/10.2307/1178008

- Brook T. (1993). Rethinking Syncretism: The Unity of the Three Teachings and their Joint Worship in Late-Imperial China. Journal of Chinese Religions, 21(1), 13-44. https://doi.org/10.1179/073776993805307448

- Ringgren H. (1969). The problems of syncretism. Scripta Instituti Donneriani Aboensis, 3. https://doi.org/10.30674/scripta.67029

- Baron R, Cara AC. (Eds.). (2011). Creolization as Cultural Creativity. University Press of Mississippi. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctt2tvc6w.

- Hutnyk J. (2005). Hybridity. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 28(1), 79-102.

- Ryoo W. (2009). Globalization, or the logic of cultural hybridization: the case of the Korean wave. Asian Journal of Communication, 19(2), 137-151. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292980902826427

- Vuong QH. (2016). Global mindset as the integration of emerging socio-cultural values through mindsponge processes: A transition economy perspective. In J. Kuada (Ed.), Global Mindsets (pp. 123-140). Routledge.

- Vuong QH, Napier NK. (2015). Acculturation and global mindsponge: An emerging market perspective. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 49, 354-367.

- Quan-Hoang Vuong. (2022). Mindsponge Theory. AISDL. https://books.google.com/books?id=OSiGEAAAQBAJ

- Nguyen MH, La VP, Le TT, Vuong QH. Introduction to Bayesian Mindsponge Framework analytics: An innovative method for social and psychological research. MethodsX, 9, 101808. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mex.2022.101808

- Vuong QH, Nguyen MH, La VP. (2022). The mindsponge and BMF analytics for innovative thinking in social sciences and humanities. Berlin, Germany: De Gruyter. ISBN (PDF): 978-83-67405-11-9; ISBN (hardcover): 978-83-67405-10-2. doi:10.2478/9788367405119

- Vuong QH. (2021). The semiconducting principle of monetary and environmental values exchange. Economics and Business Letters, 10(3), 1-9. Available from: https://osf.io/b6pwx/download.

- Small S, Blanc J.; Mental Health During COVID-19: Tam Giao and Vietnam's Response. Frontiers in Psychiatry 2021, 11, 589618, 10.3389/fpsyt.2020.589618.

- Noboru Konno; Carmela Elita Schillaci; Intellectual capital in Society 5.0 by the lens of the knowledge creation theory. Journal of Intellectual Capital 2021, 22, 478-505, 10.1108/jic-02-2020-0060.

- Luis Miguel Dos Santos; I Am a Nursing Student but Hate Nursing: The East Asian Perspectives between Social Expectation and Social Context. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 2020, 17, 2608, 10.3390/ijerph17072608.