| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Maria L Perepechaeva | -- | 1757 | 2026-02-11 11:00:52 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | Meta information modification | 1757 | 2026-02-12 01:24:04 | | |

Video Upload Options

Pharmacological compounds can disrupt glucose homeostasis, leading to impaired glucose tolerance, hyperglycemia, or newly diagnosed diabetes, as well as worsening glycemic control in patients with pre-existing diabetes. Traditional risk factors alone cannot explain the rapidly growing global incidence of diabetes. Therefore, prevention of insulin resistance could represent an effective strategy. Achieving this goal requires a deeper understanding of the mechanisms underlying the development of insulin resistance, with particular attention to the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR). AhR, a transcription factor functioning as a xenobiotic sensor, plays a key role in various molecular pathways regulating normal homeostasis, organogenesis, and immune function. Activated by a range of exogenous and endogenous ligands, AhR is involved in the regulation of glucose and lipid metabolism as well as insulin sensitivity. However, current findings remain contradictory regarding whether AhR activation exerts beneficial or detrimental effects. This narrative review summarizes recent studies exploring the role of the AhR pathway in insulin secretion and glucose homeostasis across different tissues, and discusses molecular mechanisms involved in this process. Considering that several drugs act as AhR ligands, the review also compares how these ligands affect metabolic pathways of glucose and lipid metabolism and insulin sensitivity, producing either positive or negative effects.

1. Introduction

The use of pharmacological agents can easily disrupt the balanced function of the dynamic and sensitive endocrine system. Drugs may induce endocrine disorders through various mechanisms, including alterations in hormone production, changes in the regulation and feedback of associated molecular pathways, impairment of hormone transport, and related processes[1].

Drug-induced DM represents a serious problem in clinical practice, with a higher likelihood of development in individuals predisposed to glucose metabolism disorders due to genetic factors or unhealthy lifestyle habits, including overeating and excess body weight[2][3].

The factors contributing to the development of diabetes are well studied, but traditional risk factors cannot fully explain the rapid increase in the global prevalence of this disease. Therefore, additional factors, such as exposure to various xenobiotics, are being studied[4].

Obesity induced by environmental toxins, insulin resistance, and diabetes development are known to be mediated by the ligand-activated transcription factor aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR), which functions as a xenobiotic sensor[5][6][7].

AhR is a pleiotropic transcription factor that regulates the expression of numerous genes, which may exert distinct functions in different cell types and physiological conditions.

2. Glucose Metabolism and Its Disruption Induced by Xenobiotics

Glucose homeostasis is primarily controlled by the liver, adipose tissue, and skeletal muscle[8]. Excess glucose is stored in the body as glycogen (mainly in the liver and muscles), while, when necessary, glucose can be generated from non-carbohydrate substrates through gluconeogenesis[9][10]. The principal regulators of the balance between glucose utilization and synthesis are two hormones with opposing effects—insulin and glucagon[8].

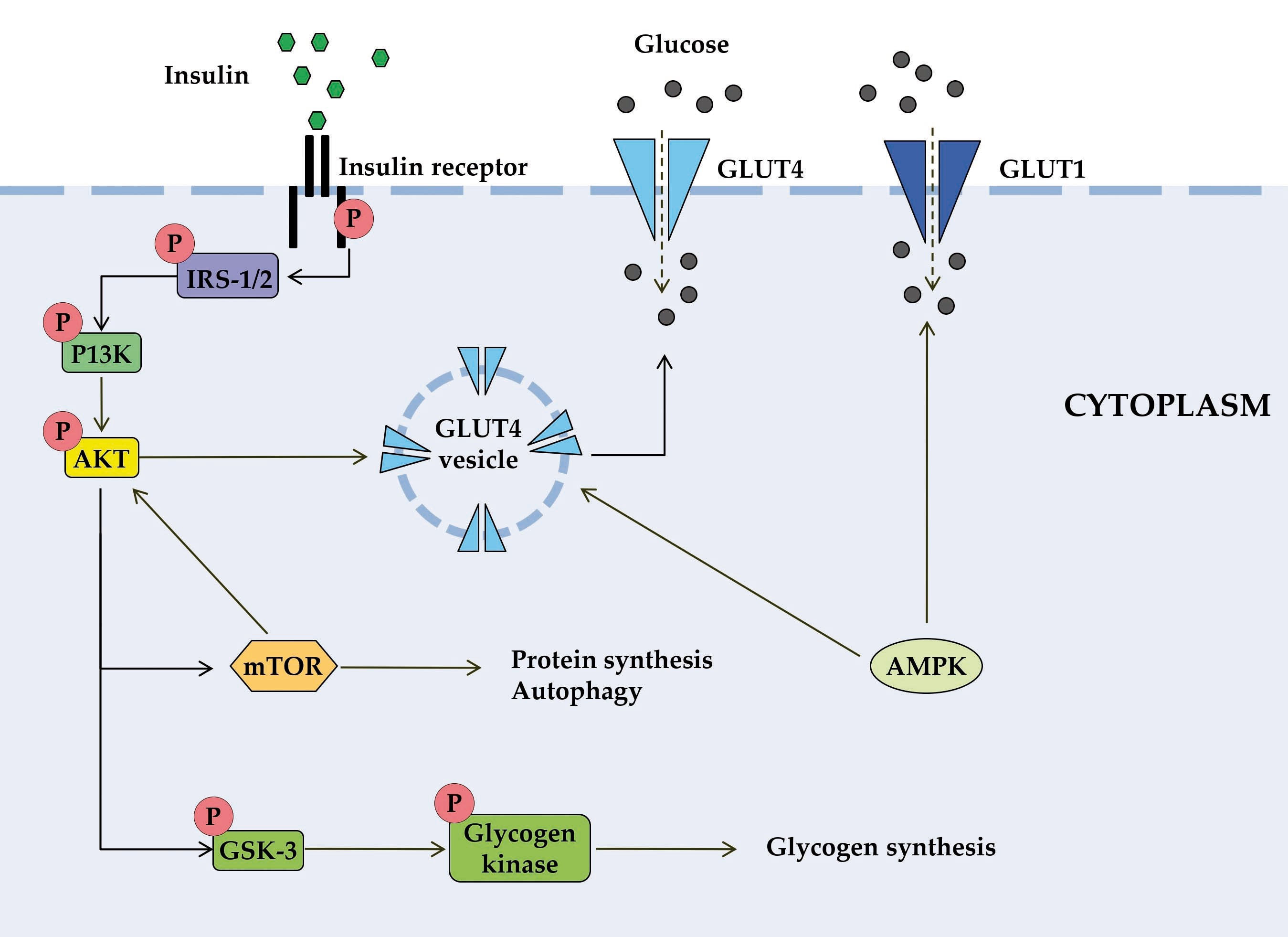

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of some signal transduction pathways initiated by insulin (highly simplified in this Figure). Insulin binds to the α-subunit of insulin receptor, causing conformational changes that allow autophosphorylation of several tyrosine residues on the β-subunit. In the AKT signaling pathway, the phosphotyrosine-binding domains of adaptor proteins, such as members of the IRS family of insulin receptor substrates, recognize β-subunit residues of the insulin receptor, leading to phosphorylation of key tyrosine residues on IRS proteins. Activation of AKT requires PI3K, which induces phosphorylation of AKT. Once activated, AKT leads to phosphorylation and inactivation of GSK, which activates glycogen synthase. AKT also directly activates the transcription factors mTOR and Fork-head. AKT plays a significant role in the translocation of GLUT4 to the plasma membrane, resulting in glucose entry into the cell. AMPK is proposed to interact with insulin signaling and GLUT4 translocation. AKT, activates protein kinase B; GLUT, glucose transporter; GSK3, glycogen synthase kinase 3; IRS, members of the insulin receptor substrate family; mTOR, mammalian target of rapamycin; PI3K, protein kinase 3′-phosphoinositide-dependent protein kinase-1.

One of the manifestations of DM is impaired lipid metabolism: elevated lipid levels are common, affect cellular metabolism, and contribute to disease progression[11]. Dysregulated lipid metabolism combined with excessive caloric intake leads to obesity, the most prevalent metabolic disorder of the endocrine system[12]. The pathophysiology of metabolic diseases is highly complex. Triggers include insufficient glucose utilization due to insulin resistance, obesity, hypercortisolemia, or receptor-mediated inhibition of serine/threonine kinases such as AKT[13]. T2DM is one of these metabolic disorders[12].

Obesity induced by environmental toxins, insulin resistance, and diabetes development are mediated by the ligand-activated transcription factor (AhR), which functions as a xenobiotic sensor. Drug-induced disruption of glucose homeostasis may also involve AhR, for which drugs act as ligands[13][14].

3. AhR

AhR is a member of the basic helix-loop-helix Per-ARNT-Sim family of transcription factors. Members of this family are involved in gene expression networks that regulate numerous physiological and developmental processes, including responses to environmental signals[15][16][17][18].

AhR role in glucose metabolism is multifaceted and affects both metabolic processes and processes such as insulin secretion, glucose uptake, and overall glucose tolerance.

AhR plays a complex role in insulin resistance. Its involvement in the regulation of proinflammatory and metabolic processes can promote the development of insulin resistance and the progression of diabetes.

4. AhR Ligands as Pharmaceutical Agents Impairing or Preventing Glucose Metabolism Dysregulation

The effects of pharmaceutical agents on glucose metabolism with potential involvement of AhR are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Effect of pharmaceutical agents on glucose metabolism with potential AhR involvement.

|

Drugs |

Therapeutic Class |

Role in AhR Signaling |

Drug-Induced Metabolic Changes with Possible Involvement of AhR Signaling |

References |

|

Glucocorticoid |

Anti-inflammatory, immune- suppressant |

Cross-talk |

Development of hxyperglycemia, insulin resistance and type 2 diabetes. Destruction of pancreatic cells |

|

|

Clozapine |

Atypical antipsychotics |

Agonist |

Hyperglycemia and insulin resistance |

|

|

Omeprazole |

Proton pump inhibitor |

Agonist, non-classic ligand (non-classic AhR signaling) |

Insulin resistance. Increased risk of T2DM with long-term use, whereas potential improvement in glycemic control in diabetic patients receiving antidiabetic agents |

|

|

Propranolol |

β-blocker |

Agonist |

Development of hypoglycemia in patients with diabetes. Impaired glucose level recovery following hypoglycemia in diabetic patients by blocking adrenaline-stimulated glucose release |

|

|

Hydroxytamoxifen (Tamoxifen metabolite) |

Selective estrogen receptor modulator |

Agonist |

Impaired β-cell secretory activity. Enhancement of insulin resistance and exacerbation of the latent risk of diabetes in predisposed women |

|

|

Ttranilast |

Antiallergic |

Agonist |

Enhancement of glucose uptake by INS-1E cells and suppression of glucose-induced insulin secretion in INS-1E cells and rat pancreatic islets. |

|

|

Leflunomide |

Antirheumatic agent |

Agonist |

Enhancing insulin sensitivity and reducing hyperglycemia in diabetic mice fed a high-fat diet |

|

|

Flutamide |

Аntiandrogen |

Agonist, selective AhR modulator |

Reduced hyperinsulinemia in women with polycystic ovary syndrome but worsened glucose intolerance with high-fat diet in experimental animals |

|

|

Statins |

HMG-CoA reductase inhibitors |

Agonist |

Insulin resistance, increasing glucose production by upregulating enzymes involved in gluconeogenesis. Increased risk of developing T2DM in patients with obesity, worsening glycemic control in patients with T2DM |

5. The Role of AhR in the Mechanisms of Action of Antidiabetic Agents

There are several examples demonstrating how AhR involvement in the action of antidiabetic drugs reveals their novel therapeutic potential.

6. Conclusions

In this review, we summarize findings that highlight the role of AhR in drug-induced glucose metabolism dysregulation. Pharmacological compounds may alter glucose homeostasis through various mechanisms, including decreased insulin sensitivity via direct intracellular pathways, promotion of weight gain, and/or functional impairment of insulin secretion—potentially involving AhR.

This applies to certain existing drugs such as glucocorticoids and estrogens, which appear to directly or indirectly affect the AhR signaling pathway. Some medications known to induce glucose metabolism disorders act as AhR ligands. Experimental studies have shown that insulin resistance and glucose depletion may occur through AhR activation leading to AKT kinase–glucose pathway blockade (as in the case of the antipsychotic drug clozapine) or via AhR-mediated induction of proinflammatory signaling (as seen with the nonselective β-blocker propranolol). A more complex relationship is observed between DM and omeprazole, a proton pump inhibitor acting as a noncanonical AhR ligand. Omeprazole-induced AhR activation can help prevent diabetic retinopathy; however, long-term exposure may lead to metabolic alterations, including increased insulin and blood glucose levels. Tamoxifen, used in hormone therapy, can increase insulin resistance and exacerbate latent diabetes risk in predisposed women. Its active metabolite, 4-hydroxytamoxifen, binds to AhR and modulates its transcriptional activity. The metabolic effects of tamoxifen and its known role in insulin resistance suggest a potential link between AhR activation and tamoxifen-induced insulin resistance, although this connection remains to be fully elucidated. Statins such as atorvastatin and pravastatin may activate AhR and promote an AhR-dependent anti-inflammatory M2 macrophage phenotype. Based on these findings, AhR has been proposed as a novel target mediating the anti-inflammatory effects of statin therapy. However, the implications of AhR inhibitors or activators for DM risk and glycemic control in statin-treated patients require further investigation.

Conversely, some AhR ligands may prevent glucose metabolism dysregulation. The anti-allergic drug tranilast, a tryptophan derivative and AhR agonist, has shown potential in the treatment of diabetic complications—an area currently under investigation. The antirheumatic drug leflunomide, also an AhR agonist, demonstrates potential antidiabetic effects by enhancing insulin sensitivity and reducing hyperglycemia, likely mediated through its AhR-dependent anti-inflammatory properties. Another AhR agonist, flutamide, a nonsteroidal antiandrogen, has been shown to reduce hyperinsulinemia. The antidiabetic agent zopolrestat, containing a benzothiazole moiety, has been developed for treating diabetic complications. Benzothiazoles, a class of bicyclic heteroaromatic compounds, are known AhR ligands.

AhR antagonists are not widely studied in relation to glucose metabolism. Drug metformin and the flavonoid quercetin are AhR antagonists, both possessing antidiabetic properties. AhR antagonists should be explored as a potential therapeutic strategy in diabetes due to their ability to reduce inflammation, improve insulin sensitivity, and mitigate obesity-associated metabolic dysfunction[49][50][51]. As for metformin and quercetin, they exemplify how AhR involvement in their mechanisms of action unveils new therapeutic potential.

AhR activation can be both a primary driver of specific drug effects (especially toxic ones) and a minor contributing factor compared to other mechanisms for these drugs in the context of broader physiological processes, depending on the specific ligand, tissue, and biological context. It is not a single, universal mechanism for all drugs and AhR acts as a complex modulator among many other biological pathways. For pharmaceuticals, the effect of AhR activation is highly variable. Some new drugs, such as tapinarof for psoriasis, are designed to target AhR as their primary therapeutic mechanism for modulating the immune response[52][53][54][55]. For many other drugs, including those described in this review, AhR activation may be a secondary effect and a minor contributor to their overall action.

In conclusion, further studies are required to elucidate the complex interplay between AhR, insulin signaling, and glucose metabolism, and to clarify the precise mechanisms through which this interaction is mediated, as current research in this area is still ongoing.

References

- E Diamanti-Kandarakis; L Duntas; G A Kanakis; E Kandaraki; N Karavitaki; E Kassi; S Livadas; G Mastorakos; I Migdalis; A D Miras; S Nader; O Papalou; R Poladian; V Popovic; D Rachoń; S Tigas; C Tsigos; T Tsilchorozidou; T Tzotzas; A Bargiota; M Pfeifer; DIAGNOSIS OF ENDOCRINE DISEASE: Drug-induced endocrinopathies and diabetes: a combo-endocrinology overview. Eur. J. Endocrinol.. 2019, 181, R73-R105.

- Bruno Fève; André J. Scheen; When therapeutic drugs lead to diabetes. Diabetol.. 2022, 65, 751-762.

- Lars Christian Lund; Patricia Hjorslev Jensen; Anton Pottegård; Morten Andersen; Nicole Pratt; Jesper Hallas; Identifying diabetogenic drugs using real world health care databases: A Danish and Australian symmetry analysis. Diabetes, Obes. Metab.. 2023, 25, 1311-1320.

- Tahseen S. Sayed; Zaid H. Maayah; Heba A. Zeidan; Abdelali Agouni; Hesham M. Korashy; Insight into the physiological and pathological roles of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor pathway in glucose homeostasis, insulin resistance, and diabetes development. Cell. Mol. Biol. Lett.. 2022, 27, 1-26.

- Karl Walter Bock; Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR), integrating energy metabolism and microbial or obesity-mediated inflammation. Biochem. Pharmacol.. 2021, 184, 114346.

- Joanna S. Kerley-Hamilton; Heidi W. Trask; Christian J.A. Ridley; Eric DuFour; Carol S. Ringelberg; Nilufer Nurinova; Diandra Wong; Karen L. Moodie; Samantha L. Shipman; Jason H. Moore; Murray Korc; Nicholas W. Shworak; Craig R. Tomlinson; Obesity Is Mediated by Differential Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Signaling in Mice Fed a Western Diet. Environ. Heal. Perspect.. 2012, 120, 1252-1259.

- Jan Aaseth; Dragana Javorac; Aleksandra Buha Djordjevic; Zorica Bulat; Anatoly V. Skalny; Irina P. Zaitseva; Michael Aschner; Alexey A. Tinkov; The Role of Persistent Organic Pollutants in Obesity: A Review of Laboratory and Epidemiological Studies. Toxics. 2022, 10, 65.

- Alan R. Saltiel. Insulin Signaling in the Control of Glucose and Lipid Homeostasis; Springer Nature: Durham, NC, United States, 2015; pp. 51-71.

- Evan Yi-Wen Yu; Zhewen Ren; Siamak Mehrkanoon; Coen D. A. Stehouwer; Marleen M. J. van Greevenbroek; Simone J. P. M. Eussen; Maurice P. Zeegers; Anke Wesselius; Plasma metabolomic profiling of dietary patterns associated with glucose metabolism status: The Maastricht Study. BMC Med.. 2022, 20, 1-16.

- Xavier Remesar; Marià Alemany; Dietary Energy Partition: The Central Role of Glucose. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2020, 21, 7729.

- Linna Xu; Qingqing Yang; Jinghua Zhou; Mechanisms of Abnormal Lipid Metabolism in the Pathogenesis of Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2024, 25, 8465.

- Arshag D Mooradian; Dyslipidemia in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Nat. Rev. Endocrinol.. 2009, 5, 150-159.

- Karin Fehsel; Metabolic Side Effects from Antipsychotic Treatment with Clozapine Linked to Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor (AhR) Activation. Biomed.. 2024, 12, 2294.

- K Fehsel; K Schwanke; Ba Kappel; E Fahimi; E Meisenzahl-Lechner; C Esser; K Hemmrich; T Haarmann-Stemmann; G Kojda; C Lange-Asschenfeldt; Activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor by clozapine induces preadipocyte differentiation and contributes to endothelial dysfunction. J. Psychopharmacol.. 2022, 36, 191-201.

- Brian E. McIntosh; John B. Hogenesch; Christopher A. Bradfield; Mammalian Per-Arnt-Sim Proteins in Environmental Adaptation. Annu. Rev. Physiol.. 2010, 72, 625-645.

- Daniel W. Nebert; Aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR): “pioneer member” of the basic-helix/loop/helix per - Arnt - sim (bHLH/PAS) family of “sensors” of foreign and endogenous signals. Prog. Lipid Res.. 2017, 67, 38-57.

- Marta Kolonko-Adamska; Vladimir N. Uversky; Beata Greb-Markiewicz; The Participation of the Intrinsically Disordered Regions of the bHLH-PAS Transcription Factors in Disease Development. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2021, 22, 2868.

- Ziyue Kou; Wei Dai; Aryl hydrocarbon receptor: Its roles in physiology. Biochem. Pharmacol.. 2021, 185, 114428-114428.

- Hong Lan Jin; Yujin Choi; Kwang Won Jeong; Crosstalk between Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor and Glucocorticoid Receptor in Human Retinal Pigment Epithelial Cells. Int. J. Endocrinol.. 2017, 2017, 1-9.

- Shoko Sato; Hitoshi Shirakawa; Shuhei Tomita; Masahiro Tohkin; Frank J. Gonzalez; Michio Komai; The aryl hydrocarbon receptor and glucocorticoid receptor interact to activate human metallothionein 2A. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol.. 2013, 273, 90-99.

- Z Dvořák; R Vrzal; P Pávek; J Ulrichová; An evidence for regulatory cross-talk between aryl hydrocarbon receptor and glucocorticoid receptor in HepG2 cells. Physiol. Res.. 2008, 57, 427-435.

- Sunghwan Suh; Mi Kyoung Park; Glucocorticoid-Induced Diabetes Mellitus: An Important but Overlooked Problem. Endocrinol. Metab.. 2017, 32, 180-189.

- Emily Au; Kristoffer J. Panganiban; Sally Wu; Kira Sun; Bailey Humber; Gary Remington; Sri Mahavir Agarwal; Adria Giacca; Sandra Pereira; Margaret Hahn; Antipsychotic-Induced Dysregulation of Glucose Metabolism Through the Central Nervous System: A Scoping Review of Animal Models. Biol. Psychiatry: Cogn. Neurosci. Neuroimaging. 2024, 10, 244-257.

- Takashi Miyakoshi; Shuhei Ishikawa; Ryo Okubo; Naoki Hashimoto; Norihiro Sato; Ichiro Kusumi; Yoichi M. Ito; Risk factors for abnormal glucose metabolism during antipsychotic treatment: A prospective cohort study. J. Psychiatr. Res.. 2023, 168, 149-156.

- Muhammad Ali Rajput; Fizzah Ali; Tabassum Zehra; Shahid Zafar; Gunesh Kumar; The effect of proton pump inhibitors on glycaemic control in diabetic patients. J. Taibah Univ. Med Sci.. 2020, 15, 218-223.

- Stefano Ciardullo; Federico Rea; Laura Savaré; Gabriella Morabito; Gianluca Perseghin; Giovanni Corrao; Prolonged Use of Proton Pump Inhibitors and Risk of Type 2 Diabetes: Results From a Large Population-Based Nested Case-Control Study. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab.. 2022, 107, e2671-e2679.

- Alina Kabaliei; Vitalina Palchyk; Olga Izmailova; Viktoriya Shynkevych; Oksana Shlykova; Igor Kaidashev; Long-Term Administration of Omeprazole-Induced Hypergastrinemia and Changed Glucose Homeostasis and Expression of Metabolism-Related Genes. BioMed Res. Int.. 2024, 2024, 1-16.

- Sinan Ai; Zhiyuan Zhang; Xiai Wu; Insulin autoimmune syndrome induced by omeprazole in an Asian Male with HLA-DRB1*0406 Subtype: A case report. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pr.. 2024, 218, 111906.

- Mónica Pombo; Michael W. Lamé; Naomi J. Walker; Danh H. Huynh; Fern Tablin; TCDD and omeprazole prime platelets through the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) non-genomic pathway. Toxicol. Lett.. 2015, 235, 28-36.

- Melanie Powis; Trine Celius; Jason Matthews; Differential ligand-dependent activation and a role for Y322 in aryl hydrocarbon receptor-mediated regulation of gene expression. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun.. 2011, 410, 859-865.

- Un-Ho Jin; Syng-Ook Lee; Catherine Pfent; Stephen Safe; The aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligand omeprazole inhibits breast cancer cell invasion and metastasis. BMC Cancer. 2014, 14, 498-498.

- Av Srinivasan; Propranolol: A 50-year historical perspective. Ann. Indian Acad. Neurol.. 2019, 22, 21-26.

- Karim Dorgham; Zahir Amoura; Christophe Parizot; Laurent Arnaud; Camille Frances; Cédric Pionneau; Hervé Devilliers; Sandra Pinto; Rima Zoorob; Makoto Miyara; Martin Larsen; Hans Yssel; Guy Gorochov; Alexis Mathian; Ultraviolet light converts propranolol, a nonselective β‐blocker and potential lupus‐inducing drug, into a proinflammatory AhR ligand. Eur. J. Immunol.. 2015, 45, 3174-3187.

- Francoise Congues; Pengcheng Wang; Joshua Lee; Daphne Lin; Ayaz Shahid; Jianming Xie; Ying Huang; Targeting aryl hydrocarbon receptor to prevent cancer in barrier organs. Biochem. Pharmacol.. 2024, 223, 116156-116156.

- Lorraine L. Lipscombe; Hadas D. Fischer; Lingsong Yun; Andrea Gruneir; Peter Austin; Lawrence Paszat; Geoff M. Anderson; Paula A. Rochon; Association between tamoxifen treatment and diabetes. Cancer. 2011, 118, 2615-2622.

- Leonard Best; Inhibition of glucose-induced electrical activity by 4-hydroxytamoxifen in rat pancreatic β-cells. Cell. Signal.. 2002, 14, 69-73.

- Nora Klöting; Matthias Kern; Michele Moruzzi; Michael Stumvoll; Matthias Blüher; Tamoxifen treatment causes early hepatic insulin resistance. Acta Diabetol.. 2020, 57, 495-498.

- Shihoko Suwa; Aya Kasubata; Miyu Kato; Megumi Iida; Ken Watanabe; Osamu Miura; Tetsuya Fukuda; The tryptophan derivative, tranilast, and conditioned medium with indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase-expressing cells inhibit the proliferation of lymphoid malignancies. Int. J. Oncol.. 2015, 46, 1369-1376.

- Gérald J. Prud'Homme; Yelena Glinka; Anna Toulina; Olga Ace; Venkateswaran Subramaniam; Serge Jothy; Breast Cancer Stem-Like Cells Are Inhibited by a Non-Toxic Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Agonist. PLOS ONE. 2010, 5, e13831.

- S. Taguchi; N. Ozaki; H. Umeda; N. Mizutani; T. Yamada; Y. Oiso; Tranilast Inhibits Glucose-induced Insulin Secretion from Pancreatic β-Cells. Horm. Metab. Res.. 2008, 40, 518-523.

- Wenyue Hu; Claudio Sorrentino; Michael S. Denison; Kyle Kolaja; Mark R. Fielden; Induction of Cyp1a1 Is a Nonspecific Biomarker of Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Activation: Results of Large Scale Screening of Pharmaceuticals and Toxicants in Vivo and in Vitro. Mol. Pharmacol.. 2007, 71, 1475-1486.

- Junhong Chen; Jing Sun; Michelle E Doscas; Jin Ye; Ashley J Williamson; Yanchun Li; Yi Li; Richard A Prinz; Xiulong Xu; Control of hyperglycemia in male mice by leflunomide: mechanisms of action. J. Endocrinol.. 2018, 237, 43-58.

- Anna Maria Paoletti; Angelo Cagnacci; Marisa Orrù; Silvia Ajossa; Stefano Guerriero; Gian Benedetto Melis; Treatment with flutamide improves hyperinsulinemia in women with idiopathic hirsutism. Fertil. Steril.. 1999, 72, 448-453.

- Xiaoxia Gao; Cen Xie; Yuanyuan Wang; Yuhong Luo; Tomoki Yagai; Dongxue Sun; Xuemei Qin; Kristopher W. Krausz; Frank J. Gonzalez; The antiandrogen flutamide is a novel aryl hydrocarbon receptor ligand that disrupts bile acid homeostasis in mice through induction of Abcc4. Biochem. Pharmacol.. 2016, 119, 93-104.

- Jing Hu; Yanan Yang; Shaoting Fu; Xiaohan Yu; Xiaohui Wang; Exercise improves glucose and lipid metabolism in high fat diet feeding male mice through androgen/androgen receptor-mediated metabolism regulatory factors. Biochim. et Biophys. Acta (BBA) - Mol. Basis Dis.. 2025, 1871, 167926.

- Angeliki M. Angelidi; Emelina Stambolliu; Konstantina I. Adamopoulou; Antonis A. Kousoulis; Is Atorvastatin Associated with New Onset Diabetes or Deterioration of Glycemic Control? Systematic Review Using Data from 1.9 Million Patients. Int. J. Endocrinol.. 2018, 2018, 1-17.

- Antonella Turco; Giulia Scalisi; Marco Gargaro; Matteo Pirro; Francesca Fallarino; Aryl hydrocarbon receptor: a novel target for the anti-inflammatory activity of statin therapy. J. Immunol.. 2017, 198, 67.10-67.10.

- Hye Jin Wang; Jae Yeo Park; Obin Kwon; Eun Yeong Choe; Chul Hoon Kim; Kyu Yeon Hur; Myung-Shik Lee; Mijin Yun; Bong Soo Cha; Young-Bum Kim; Hyangkyu Lee; Eun Seok Kang; Chronic HMGCR/HMG-CoA reductase inhibitor treatment contributes to dysglycemia by upregulating hepatic gluconeogenesis through autophagy induction. Autophagy. 2015, 11, 2089-2101.

- Sora Kang; Aden Geonhee Lee; Suyeol Im; Seung Jun Oh; Hye Ji Yoon; Jeong Ho Park; Youngmi Kim Pak; A Novel Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Antagonist HBU651 Ameliorates Peripheral and Hypothalamic Inflammation in High-Fat Diet-Induced Obese Mice. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2022, 23, 14871.

- Nathaniel G. Girer; Craig R. Tomlinson; Cornelis J. Elferink; The Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor in Energy Balance: The Road from Dioxin-Induced Wasting Syndrome to Combating Obesity with Ahr Ligands. Int. J. Mol. Sci.. 2020, 22, 49.

- Itzel Y. Rojas; Benjamin J. Moyer; Carol S. Ringelberg; Craig R. Tomlinson; Reversal of obesity and liver steatosis in mice via inhibition of aryl hydrocarbon receptor and altered gene expression of CYP1B1, PPARα, SCD1, and osteopontin. Int. J. Obes.. 2020, 44, 948-963.

- Susan H. Smith; Channa Jayawickreme; David J. Rickard; Edwige Nicodeme; Thi Bui; Cathy Simmons; Christine M. Coquery; Jessica Neil; William M. Pryor; David Mayhew; Deepak K. Rajpal; Katrina Creech; Sylvia Furst; James Lee; Dalei Wu; Fraydoon Rastinejad; Timothy M. Willson; Fabrice Viviani; David C. Morris; John T. Moore; Javier Cote-Sierra; Tapinarof Is a Natural AhR Agonist that Resolves Skin Inflammation in Mice and Humans. J. Investig. Dermatol.. 2017, 137, 2110-2119.

- Jonathan I. Silverberg; Mark Boguniewicz; Francisco J. Quintana; Rachael A. Clark; Lara Gross; Ikuo Hirano; Anna M. Tallman; Philip M. Brown; Doral Fredericks; David S. Rubenstein; Kimberly A. McHale; Tapinarof validates the aryl hydrocarbon receptor as a therapeutic target: A clinical review. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol.. 2023, 154, 1-10.

- Susan H. Smith; Channa Jayawickreme; David J. Rickard; Edwige Nicodeme; Thi Bui; Cathy Simmons; Christine M. Coquery; Jessica Neil; William M. Pryor; David Mayhew; Deepak K. Rajpal; Katrina Creech; Sylvia Furst; James Lee; Dalei Wu; Fraydoon Rastinejad; Timothy M. Willson; Fabrice Viviani; David C. Morris; John T. Moore; Javier Cote-Sierra; Tapinarof Is a Natural AhR Agonist that Resolves Skin Inflammation in Mice and Humans. J. Investig. Dermatol.. 2017, 137, 2110-2119.

- Jonathan I. Silverberg; Mark Boguniewicz; Francisco J. Quintana; Rachael A. Clark; Lara Gross; Ikuo Hirano; Anna M. Tallman; Philip M. Brown; Doral Fredericks; David S. Rubenstein; Kimberly A. McHale; Tapinarof validates the aryl hydrocarbon receptor as a therapeutic target: A clinical review. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol.. 2023, 154, 1-10.