| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ana Ibáñez | -- | 2059 | 2026-02-05 10:31:05 | | | |

| 2 | Ana Ibáñez | + 13 word(s) | 2072 | 2026-02-05 10:44:15 | | |

Video Upload Options

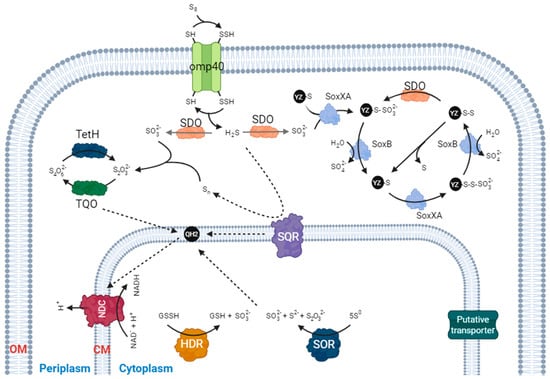

Sulfur oxidation is a cornerstone of the Earth’s sulfur cycle, and members of the genus Acidithiobacillus play a central role as highly specialized sulfur-oxidizing bacteria. These microorganisms are capable of efficiently oxidizing a wide range of reduced inorganic sulfur compounds (RISCs) under extreme acidic conditions, sustaining their autotrophic growth in environments that are inhospitable to most life forms. This metabolic versatility has positioned Acidithiobacillus species as key biological agents in industrial applications such as bioleaching for metal recovery and biological desulfurization processes in bioremediation.

This Encyclopedia entry provides a comprehensive review of the current knowledge on sulfur metabolism in Acidithiobacillus, summarizing the main oxidation pathways described to date and the regulatory mechanisms that coordinate them. While significant advances have been achieved through genomic, transcriptomic, and biochemical studies, the sulfur oxidation network in these bacteria remains only partially understood. Many enzymatic steps, regulatory links, and environmental triggers are still unresolved, highlighting the complexity of sulfur metabolism and the need for further research to fully exploit the biotechnological potential of Acidithiobacillus species.

1. Introduction

2. Sulfur Dioxygenase (SDO)

3. Sulfur Oxygenase Reductase (SOR)

4. Heterodisulfide Reductase (HDR)-like System

References

- Rouchalova, D.; Rouchalova, K.; Janakova, I.; Cablik, V.; Janstova, S. Bioleaching of Iron, Copper, Lead, and Zinc from the Sludge Mining Sediment at Different Particle Sizes, pH, and Pulp Density Using Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. Minerals 2020, 10, 1013.

- Wu, W.; Pang, X.; Lin, J.; Liu, X.; Wang, R.; Lin, J.; Chen, L. Discovery of a New Subgroup of Sulfur Dioxygenases and Characterization of Sulfur Dioxygenases in the Sulfur Metabolic Network of Acidithiobacillus caldus. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0183668.

- Valenzuela, L.; Chi, A.; Beard, S.; Shabanowitz, J.; Hunt, D.F.; Jerez, C.A. Differential-Expression Proteomics for the Study of Sulfur Metabolism in the Chemolithoautotrophic Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans. In Microbial Sulfur. Metabolism; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germnay, 2008; pp. 77–86.

- Suzuki, I.; Werkman, C.H. Glutathione and Sulfuroxidation by Thiobacillus thiooxidans. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1959, 45, 239–244.

- Wang, Z.; Gerstein, M.; Snyder, M. RNA-Seq: A Revolutionary Tool for Transcriptomics. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 57–63.

- Kucera, J.; Pakostova, E.; Janiczek, O.; Mandl, M. Changes in Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans Ability to Reduce Ferric Iron by Elemental Sulfur. Adv. Mat. Res. 2015, 1130, 97–100.

- Rahman, P.K.S.M.; Gakpe, E. Production, Characterisation and Applications of Biosurfactants-Review. Biotechnology 2008, 7, 360–370.

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Liu, J.; Qiu, G. Isolation and Characterization of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans Strain QXS-1 Capable of Unusual Ferrous Iron and Sulfur Utilization. Hydrometallurgy 2013, 136, 51–57.

- Lee, S.-Y.; Kim, E.-G.; Park, J.-R.; Ryu, Y.-H.; Moon, W.; Park, G.-H.; Ubaidillah, M.; Ryu, S.-N.; Kim, K.-M. Effect on Chemical and Physical Properties of Soil Each Peat Moss, Elemental Sulfur, and Sulfur-Oxidizing Bacteria. Plants 2021, 10, 1901.

- Liljeqvist, M.; Rzhepishevska, O.I.; Dopson, M. Gene Identification and Substrate Regulation Provide Insights into Sulfur Accumulation during Bioleaching with the Psychrotolerant Acidophile Acidithiobacillus ferrivorans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2013, 79, 951–957.

- Kanao, T.; Onishi, M.; Kajitani, Y.; Hashimoto, Y.; Toge, T.; Kikukawa, H.; Kamimura, K. Characterization of Tetrathionate Hydrolase from the Marine Acidophilic Sulfur-Oxidizing Bacterium, Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans Strain SH. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2018, 82, 152–160.

- Silver, M.; Lundgren, D.G. Sulfur-Oxidizing Enzyme of Ferrobacillus ferrooxidans (Thiobacillus ferrooxidans). Can. J. Biochem. 1968, 46, 457–461.

- Sugio, T.; Mizunashi, W.; Inagaki, K.; Tano, T. Purification and Some Properties of Sulfur:Ferric Ion Oxidoreductase from Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. J. Bacteriol. 1987, 169, 4916–4922.

- Suzuki, I. Oxidation of Elemental Sulfur by an Enzyme System of Thiobacillus thiooxidans. Biochim. Biophys. Acta (BBA)—General. Subj. 1965, 104, 359–371.

- Wang, H.; Liu, S.; Liu, X.; Li, X.; Wen, Q.; Lin, J. Identification and Characterization of an ETHE1-like Sulfur Dioxygenase in Extremely Acidophilic Acidithiobacillus spp. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2014, 98, 7511–7522.

- Sattler, S.A.; Wang, X.; Lewis, K.M.; DeHan, P.J.; Park, C.-M.; Xin, Y.; Liu, H.; Xian, M.; Xun, L.; Kang, C. Characterizations of Two Bacterial Persulfide Dioxygenases of the Metallo-β-Lactamase Superfamily. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 18914–18923.

- Liu, H.; Xin, Y.; Xun, L. Distribution, Diversity, and Activities of Sulfur Dioxygenases in Heterotrophic Bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 1799–1806.

- Jackson, M.R.; Melideo, S.L.; Jorns, M.S. Human Sulfide:Quinone Oxidoreductase Catalyzes the First Step in Hydrogen Sulfide Metabolism and Produces a Sulfane Sulfur Metabolite. Biochemistry 2012, 51, 6804–6815.

- Grings, M.; Seminotti, B.; Karunanidhi, A.; Ghaloul-Gonzalez, L.; Mohsen, A.-W.; Wipf, P.; Palmfeldt, J.; Vockley, J.; Leipnitz, G. ETHE1 and MOCS1 Deficiencies: Disruption of Mitochondrial Bioenergetics, Dynamics, Redox Homeostasis and Endoplasmic Reticulum-Mitochondria Crosstalk in Patient Fibroblasts. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 12651.

- Kabil, O.; Banerjee, R. Characterization of Patient Mutations in Human Persulfide Dioxygenase (ETHE1) Involved in H2S Catabolism. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 44561–44567.

- Rohwerder, T.; Sand, W. The Sulfane Sulfur of Persulfides Is the Actual Substrate of the Sulfur-Oxidizing Enzymes from Acidithiobacillus and Acidiphilium spp. Microbiology 2003, 149, 1699–1710.

- Guiliani, N.; Jerez, C.A. Molecular Cloning, Sequencing, and Expression of omp-40, the Gene Coding for the Major Outer Membrane Protein from the Acidophilic Bacterium Thiobacillus ferrooxidans. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 2318–2324.

- Ramírez, P.; Guiliani, N.; Valenzuela, L.; Beard, S.; Jerez, C.A. Differential Protein Expression during Growth of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans on Ferrous Iron, Sulfur Compounds, or Metal Sulfides. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 4491–4498.

- Peng, T.; Chen, L.; Wang, J.; Miao, J.; Shen, L.; Yu, R.; Gu, G.; Qiu, G.; Zeng, W. Dissolution and Passivation of Chalcopyrite during Bioleaching by Acidithiobacillus ferrivorans at Low Temperature. Minerals 2019, 9, 332.

- Janosch, C.; Remonsellez, F.; Sand, W.; Vera, M. Sulfur Oxygenase Reductase (Sor) in the Moderately Thermoacidophilic Leaching Bacteria: Studies in Sulfobacillus thermosulfidooxidans and Acidithiobacillus caldus. Microorganisms 2015, 3, 707–724.

- Chen, Z.-W.; Liu, Y.-Y.; Wu, J.-F.; She, Q.; Jiang, C.-Y.; Liu, S.-J. Novel Bacterial Sulfur Oxygenase Reductases from Bioreactors Treating Gold-Bearing Concentrates. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2007, 74, 688–698.

- You, X.-Y.; Guo, X.; Zheng, H.-J.; Zhang, M.-J.; Liu, L.-J.; Zhu, Y.-Q.; Zhu, B.; Wang, S.-Y.; Zhao, G.-P.; Poetsch, A.; et al. Unraveling the Acidithiobacillus caldus Complete Genome and Its Central Metabolisms for Carbon Assimilation. J. Genet. Genom. 2011, 38, 243–252.

- Lee, Y.; Sethurajan, M.; van de Vossenberg, J.; Meers, E.; van Hullebusch, E.D. Recovery of Phosphorus from Municipal Wastewater Treatment Sludge through Bioleaching Using Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans. J. Environ. Manag. 2020, 270, 110818.

- Valdés, J.; Pedroso, I.; Quatrini, R.; Holmes, D.S. Comparative Genome Analysis of Acidithiobacillus ferrooxidans, A. thiooxidans and A. caldus: Insights into Their Metabolism and Ecophysiology. Hydrometallurgy 2008, 94, 180–184.

- Chen, L.; Ren, Y.; Lin, J.; Liu, X.; Pang, X.; Lin, J. Acidithiobacillus caldus Sulfur Oxidation Model Based on Transcriptome Analysis between the Wild Type and Sulfur Oxygenase Reductase Defective Mutant. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e39470.

- Yin, H.; Zhang, X.; Li, X.; He, Z.; Liang, Y.; Guo, X.; Hu, Q.; Xiao, Y.; Cong, J.; Ma, L.; et al. Whole-Genome Sequencing Reveals Novel Insights into Sulfur Oxidation in the Extremophile Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans. BMC Microbiol. 2014, 14, 179.

- Liu, L.-J.; Stockdreher, Y.; Koch, T.; Sun, S.-T.; Fan, Z.; Josten, M.; Sahl, H.-G.; Wang, Q.; Luo, Y.-M.; Liu, S.-J.; et al. Thiosulfate Transfer Mediated by DsrE/TusA Homologs from Acidothermophilic Sulfur-Oxidizing Archaeon Metallosphaera cuprina. J. Biol. Chem. 2014, 289, 26949–26959.

- Dahl, C. Cytoplasmic Sulfur Trafficking in Sulfur-Oxidizing Prokaryotes. IUBMB Life 2015, 67, 268–274.

- Ehrenfeld, N.; Levicán, G.J.; Parada, P. Heterodisulfide Reductase from Acidithiobacilli is a Key Component Involved in Metabolism of Reduced Inorganic Sulfur Compounds. Adv. Mat. Res. 2013, 825, 194–197.

- Camacho, D.; Frazao, R.; Fouillen, A.; Nanci, A.; Lang, B.F.; Apte, S.C.; Baron, C.; Warren, L.A. New Insights into Acidithiobacillus thiooxidans Sulfur Metabolism Through Coupled Gene Expression, Solution Chemistry, Microscopy, and Spectroscopy Analyses. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 411.

- Koch, T.; Dahl, C. A Novel Bacterial Sulfur Oxidation Pathway Provides a New Link between the Cycles of Organic and Inorganic Sulfur Compounds. ISME J. 2018, 12, 2479–2491.

- Cao, X.; Koch, T.; Steffens, L.; Finkensieper, J.; Zigann, R.; Cronan, J.E.; Dahl, C. Lipoate-Binding Proteins and Specific Lipoate-Protein Ligases in Microbial Sulfur Oxidation Reveal an Atypical Role for an Old Cofactor. Elife 2018, 7, e37439.

- Tabita, R.; Silver, M.; Lundgren, D.G. The Rhodanese Enzyme of Ferrobacillus ferrooxidans (Thiobacillus ferrooxidans). Can. J. Biochem. 1969, 47, 1141–1145.

- Gardner, M.N.; Rawlings, D.E. Production of Rhodanese by Bacteria Present in Bio-Oxidation Plants Used to Recover Gold from Arsenopyrite Concentrates. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2000, 89, 185–190.

- Berlemont, R.; Gerday, C. Extremophiles. In Comprehensive Biotechnology; Moo-Young, M., Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 229–242. ISBN 978-0-08-088504-9.