| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Martin George Wynn | -- | 652 | 2026-01-07 01:48:51 | | | |

| 2 | Abigail Zou | Meta information modification | 652 | 2026-01-07 06:46:32 | | | | |

| 3 | Abigail Zou | + 2 word(s) | 654 | 2026-01-22 07:47:14 | | |

Video Upload Options

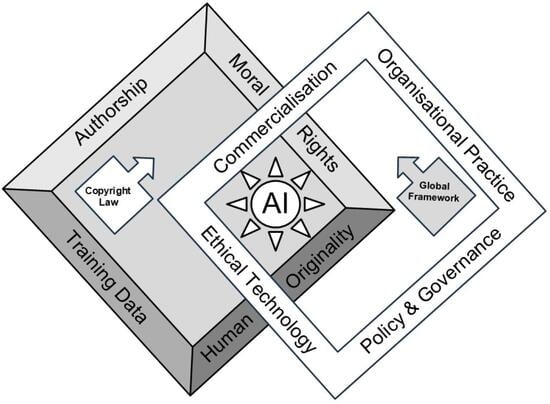

This entry explores the implications of generative AI for the underlying foundational premises of copyright law and the potential threat it poses to human creativity. It identifies the gaps and inconsistencies in legal frameworks as regards authorship, training-data use, moral rights, and human originality in the context of AI systems that are capable of imitating human expression at both syntactic and semantic levels. The entry includes: (i) a comparative analysis of the legal frameworks of the United Kingdom, United States, and Germany, using the Berne Convention as a harmonising baseline, (ii) a systematic synthesis of the relevant academic literature, and (iii) insights gained from semi-structured interviews with legal scholars, AI developers, industry stakeholders, and creators. Evidence suggests that existing laws are ill-equipped for semantic and stylistic reproduction; there is no agreement on authorship, no clear licensing model for training data, and inadequate protection for the moral identity of creators—especially posthumously, where explicit protections for likeness, voice, and style are fragmented. The entry puts forward a draft global framework to restore legal certainty and cultural value, incorporating a semantics-aware definition of the term “work”, and encompassing licensing and remuneration of training data, enhanced moral and posthumous rights, as well as enforceable transparency. At the same time, parallel personality-based safeguards, including rights of publicity, image, or likeness, although present in all three jurisdictions studied, are not subject to the same copyright and thus do not offer any coherent or adequate protection against semantic or stylistic imitation, which once again highlights the need for a more unified and robust copyright strategy.

References

- Turvill, W. Elton and Paul in harmony over the dangers of AI. Sunday Times Business and Money. 26 January 2025. Available online: https://www.thetimes.com/business-money (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Neubauer, A. AI and Authorship Redefined—Towards a Global Copyright Framework for Commerce and Human Originality. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Gloucestershire, Cheltenham, UK, 2025.