| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Giovanna Giovinazzo | + 1713 word(s) | 1713 | 2020-12-16 09:32:21 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 1713 | 2021-01-06 10:22:10 | | |

Video Upload Options

SARS-CoV-2 first emerged in China during late 2019 and rapidly spread all over the world. Alterations in the inflammatory cytokines pathway represent a strong signature during SARS-COV-2 infection and correlate with poor prognosis and severity of the illness. The hyper-activation of the immune system results in an acute severe systemic inflammatory response named cytokine release syndrome (CRS). No effective prophylactic or post-exposure treatments are available, although some anti-inflammatory compounds are currently in clinical trials. Studies of plant extracts and natural compounds show that polyphenols can play a beneficial role in the prevention and the progress of chronic diseases related to inflammation. The aim of this manuscript is to review the published background on the possible effectiveness of polyphenols to fight SARS-COV-2 infection, contributing to the reduction of inflammation. Here, some of the anti-inflammatory therapies are discussed and although great progress has been made though this year, there is no proven cytokine blocking agents for COVID currently used in clinical practice. In this regard, bioactive phytochemicals such as polyphenols may become promising tools to be used as adjuvants in the treatment of SARS-CoV-2 infection. Such nutrients, with anti-inflammatory and antioxidant properties, associated to classical anti-inflammatory drugs, could help in reducing the inflammation in patients with COVID-19.

1. Polyphenols as Natural Molecules with Anti-Inflammatory Activity

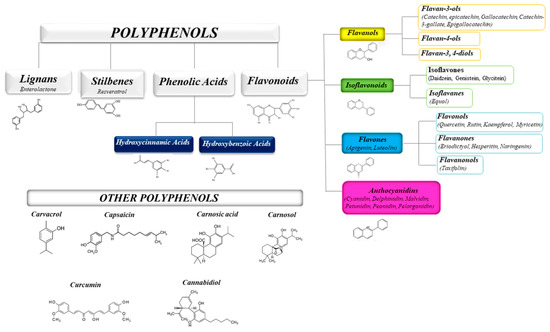

The health-promoting activities of plant polyphenols have been widely ascertained by numerous scientific publications. Studies on plant extracts and phytochemicals showed that polyphenols can play an anti-inflammatory action in the prevention and the progression of chronic diseases [1][2][3][4][5]. Polyphenols are ubiquitous in plants, being the products of plants’ secondary metabolism present either as glycosides or as free aglycones [6] (Figure 1). Thousands of structural variants (more than 8000) exist in the polyphenol family. In the plant kingdom, polyphenols determinate color, flavor, and defense activity [2]. They are grouped according to chemical structures into flavonoids such as flavones, flavonols, flavanol isoflavones, anthocyanins, proanthocyanidins, and non flavonoids, such as phenolic acids, and stilbenes [7][8]. Nowadays, the consumers prefer using natural food ingredients due to their plethora of healthy properties [9][10].

Figure 1. Schematic classification of the polyphenol family and flavonoid groups putatively exploited as antiviral phytochemical.

The anti-inflammatory activity of plant polyphenols has been demonstrated by in vitro and in vivo studies supporting their role as therapeutic tools in different acute and chronic disorders [5][11][12].

The ability of polyphenols to modulate the expression of several pro-inflammatory genes as well as the immune system, in addition to their anti-oxidant activity, contributes to the regulation of inflammatory signaling [13][14][15] (see Table 1).

Table 1. Natural polyphenols and their anti-inflammatory activity.

| Plant Natural Products | Models of Inflammation | Main Effects on Inflammation | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Capsaicin, Carvacrol | Various in vitro and in vivo animal models (e.g., LPS-induced inflammation) | Inhibition of the production of TNF-α, activation of PPAR-α and γ and suppresses COX-2 expression | [16][17][18] |

| Lignans, Flavonoids | In-vitro studies in cells |

|

[2][19] |

| Curcumin, Apigenin, Quercetin, Cinnamaldehyde, Resveratrol Epigallocatechin-3-gallate |

|

|

[6][17][19][20][21][22][23] |

| Catethin, Epicatechin |

|

|

[4][5][24] |

| Carnosolic acid, Carnosol | Fusion receptor of the yeast Gal4-DNA binding domain joined to the hinge region and ligand binding domain of the human PPARγ in combination with a Gal4-driven luciferase reporter gene, cotransfected into Cos7 cells | Activation of Gal4-PPAR-γ fusion receptor, in a concentration-dependent manner. | [17][25] |

| Various polyphenols | LPS induced Inflammation in bone marrow derived dendritic cells | Reduction in IL-6, IL-12 and TNF-α levels | [26] |

| 3-Hydroxyanthranilic acid | LPS-induced inflammation in RAW 264.7 and in peritoneal macrophages | Reduction of NO, IL-1β, IL-6 and TNF-α expression; a significant increase in IL-10 expression; reduction in NFκB activity | [27] |

| Curcumin analog EF31 | LPS-induced inflammation in RAW 264.7 cells | Inhibition of the expression and secretion of TNF-α, IL-1-β, and IL-6 | [28] |

| Anthocyanins | Humans | Reduction of inflammation score in patients’ blood, reflected by decreasing serum levels of IL-6, IL-12, and high sensitivity C reactive protein | [29] |

| Ferulic acid, Coumaric acid | LPS-induced inflammation in RAW 264.7 cells | Reduction of the production of TNF-α, interleukine-1-beta (IL-1-β) and IL-6 expression | [30] |

| Syringic, Vanillic, p-Hydroxybenzoic acids | LPS-induced inflammation in RAW 264.7 cells | Reduction of iNOS, COX-2, IL-1β, TNF-α, and IL-6 | [31] |

Indeed, resveratrol from red wine showed an anti-atherogenesis property mainly due to its anti-inflammatory properties. In vivo and in vitro studies (in murine and rat macrophages) showed that resveratrol inhibited COX, peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma (PPARγ), and activated eNOS (endothelial nitric oxide synthase) [24][26][27][32]. Curcumin and its chemical analogues were shown to inhibit NF-κB activated by several different inflammatory stimuli [21][33]. Moreover, curcumin and analogues reduced the expression of inflammatory cytokines: tumor necrosis factor (TNF) and IL-1, adhesion molecules like intercellular adhesion molecule-1 (ICAM-1), and vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 (VCAM-1) in human cell systems.

Macrophages are affected by polyphenols as well. Macrophages initiate inflammation by secreting pro-inflammatory mediators and cytokines like IL-6 and TNF-α. Polyphenols such as ferulic acid and coumaric acid (from propolis) reduce the production of TNF-α, interleukine-1-beta (IL-1-β) and IL-6 expression by inhibiting cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2), and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) [22][23][28][34][35].

2. Polyphenols and Cytokine Modulation

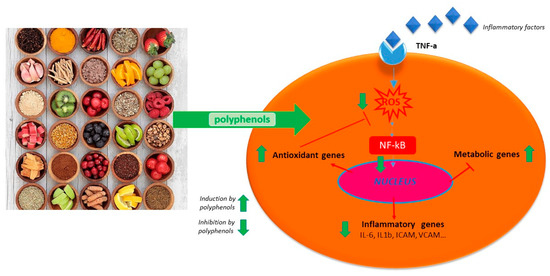

Polyphenols act on macrophages by inhibiting some of the key regulators of the inflammatory response such as TNF-α, IL-1-β, and IL-6 (Figure 1). A diet abundant in fruits rich in anthocyanins (such as red berry fruits) is related to a lower serum levels of IL-6, IL-12, and high sensitivity C reactive protein and therefore, to a decreased inflammation score in patient blood [35]. Moreover, polyphenol-enriched extra virgin olive oil and olive vegetation water have shown the capacity to reduce IL-6 and C-reactive protein expression. They also inhibit the production of TNF-α, which is usually activated by inflammation during a clinical trial on stable coronary heart disease patients and in vivo model system [29][34][36]. Table 1 shows the flavonoids able to inhibit the expression of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8, in several in vitro cell systems [13][24]. In addition, propolis extracts act as inhibitor on TNF-α, IL-1-β, and IL-6 in murine macrophages stimulated by LPS [37][38][39]. Likewise, polyphenols extract of chamomile, and isolated polyphenols such as quercetin from the extract, reduced the secretion of TNF-α and IL-6 without IL-1β modulation [30]. Polyphenols like quercetin and catechins work by balancing pro- and anti-inflammatory cytokines production; they enhance IL-10 release while inhibit TNFα and IL-1β [40] (Figure 2). A diet rich in such compounds may help patients with COVID-19 to reduce their inflammation due to the hyper-activation of cytokines such as TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, and IL-8.

Figure 2. Schematic anti-inflammatory activities of natural polyphenols.

3. Active Anti-Inflammatory Plant Extracts

In several studies, the biological activities have been evaluated by utilizing isolated single natural biomolecule. This approach was demonstrated to have both advantages and disadvantages. Advantages are a better understanding of a purified active molecule mechanism of action, and performing slight modifications on its structure to obtain molecules more efficacious (Table 1).

Polyphenols isolated from red wine, such as flavonols, soluble acids, and stilbenes such as trans-resveratrol were found to have anti-inflammatory effects [3]. Studies confirmed the anti-inflammatory activities of quercetin extracted from onions (Allium cepa), grape (Vitis vinifera L.), and red wine [3][28][41][42].

The anti-inflammatory activity of Houttuynia cordata Thunb., a perennial herbaceous plant mostly distributed in East Asia, has been studied [31]. Nowadays, fresh leaves of H. cordata are considered for a high-value industrial crop in Thailand and it has been fermented with probiotic bacteria to yield a fermentation product (HCFP) commercially available. The anti-inflammatory activities of aqueous and methanolic HCFP phenolic extracts have been demonstrated, and they are manifested by inhibiting the production of NO, PGE2, and inflammatory cytokines such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6, in in vitro and in vivo assays (see Table 1).

Moreover, cannabinoids can suppress the immune activation and inflammatory cytokine production [43]. CB1 and CB2 are receptors for endocannabinoid. While CB1 is expressed overall in the central nervous system [3], CB2 is expressed by varieties of immune cells and in lymphoid tissues, airway tissues respond to both CB2 receptor-dependent and independent effects of cannabinoids [44][45][46]. Activation of CB2 receptor can suppress the release of inflammatory IL-1, IL-6, IL-12, and TNF-α [47].

Scientific data increasingly confirm the idea that the immunomodulatory approach targeting the over-production of cytokines could be proposed for viral pulmonary disease treatment. The peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor PPAR-γ, a member of the PPAR transcription factor family, also represses the inflammatory process and could represent a potential target [17]. In Table 1, we review the main nutritional PPAR-γ ligands, suggesting an approach based on the strengthening of the immune system exploiting dietary strategies as an attempt to contrast the rising of cytokine storm in the case of coronavirus infection. In addition, nutritional ligands of PPAR-like curcumin, carvacrol, carnosol, and capsaicin, possess anti-inflammatory properties through PPAR-activation.

4. Anti-Inflammatory and Anti-Viral Activity: The Case of Resveratrol

Among non flavonoid bioactive polyphenols, resveratrol has been studied for its capability to inhibit the growth of bacteria, fungi, viruses, and for its anti-inflammatory activity [48][49][50]. In particular, resveratrol inhibits virus-induced inflammatory mediators and the replication of several respiratory viruses such as rhinovirus, influenza A virus, respiratory syncytial virus, Middle East respiratory syndrome-coronavirus (MERS-CoV), and human meta pneumovirus [51][52][53][54][55]. It has been demonstrated that resveratrol could counteract the MERS-CoV-inducing apoptosis by down-regulating FGF-2 signaling [25]. Moreover, resveratrol may inhibit the NF-κB pathway activated by MERS-CoV, reducing inflammation [56][57]. Resveratrol could be used in patients with COVID-19 as well.

The therapeutic application of resveratrol as anti-inflammatory agent was delayed due to the low bioavailability. A recently published study reported the anti-inflammatory and anti-viral solution containing resveratrol plus carboxymethyl-β-glucan in children with allergic rhinitis and acute rhinopharyngitis [58][59]. The positive effects observed might be related to resveratrol and to the immune-modulation and osmotic activities provided by the glucan [60][61].

References

- Andriantsitohaina, R.; Auger, C.; Chataigneau, T.; Étienne-Selloum, N.; Li, H.; Martínez, M.C.; Schini-Kerth, V.B.; Laher, I. Molecular mechanisms of the cardiovascular protective effects of polyphenols. Br. J. Nutr 2012, 108, 1532–1549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azab, A.; Nassar, A.; Azab, A. Anti-Inflammatory activity of natural products. Molecules 2016, 21, 1321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calabriso, N.; Massaro, M.; Scoditti, E.; Pellegrino, M.; Ingrosso, I.; Giovinazzo, G.; Carluccio, M. Red grape skin polyphenols blunt matrix metalloproteinase-2 and -9 activity and expression in cell models of vascular inflammation: Protective role in degenerative and inflammatory diseases. Molecules 2016, 21, 1147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spagnuolo, C.; Russo, M.; Bilotto, S.; Tedesco, I.; Laratta, B.; Russo, G.L. Dietary polyphenols in cancer prevention: The example of the flavonoid quercetin in leukemia: Quercetin in cancer prevention and therapy. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2012, 1259, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yahfoufi, N.; Alsadi, N.; Jambi, M.; Matar, C. The immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory role of polyphenols. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, R. Chemistry and biochemistry of dietary polyphenols. Nutrients 2010, 2, 1231–1246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovinazzo, G.; Grieco, F. Functional properties of grape and wine polyphenols. Plant. Foods Hum. Nutr. 2015, 70, 454–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Yagiz, Y.; Hsu, W.-Y.; Simonne, A.; Lu, J.; Marshall, M.R. Antioxidant, antibacterial, and antibiofilm properties of polyphenols from muscadine grape (Vitis rotundifolia Michx.) pomace against selected foodborne pathogens. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2014, 62, 6640–6649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scalbert, A.; Manach, C.; Morand, C.; Rémésy, C.; Jiménez, L. Dietary polyphenols and the prevention of diseases. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2005, 45, 287–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, G.-Y.; Zhao, C.-N.; Liu, Q.; Feng, X.-L.; Xu, X.-Y.; Cao, S.-Y.; Meng, X.; Li, S.; Gan, R.-Y.; Li, H.-B. Potential of grape wastes as a natural source of bioactive compounds. Molecules 2018, 23, 2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, C.M.; Sandrasaigaran, P.; Tong, C.K.; Adam, A.; Ramasamy, R. Immunomodulatory activity of polyphenols derived from Cassia auriculata flowers in aged rats. Cell. Immunol. 2011, 271, 474–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malireddy, S.; Kotha, S.R.; Secor, J.D.; Gurney, T.O.; Abbott, J.L.; Maulik, G.; Maddipati, K.R.; Parinandi, N.L. Phytochemical antioxidants modulate mammalian cellular epigenome: Implications in health and disease. Antioxid. Redox Signal. 2012, 17, 327–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ribeiro, A.; Almeida, V.I.; Costola-de-Souza, C.; Ferraz-de-Paula, V.; Pinheiro, M.L.; Vitoretti, L.B.; Gimenes-Junior, J.A.; Akamine, A.T.; Crippa, J.A.; Tavares-de-Lima, W.; et al. Cannabidiol improves lung function and inflammation in mice submitted to LPS-induced acute lung injury. Immunopharmacol. Immunotoxicol. 2015, 37, 35–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuolo, F.; Petronilho, F.; Sonai, B.; Ritter, C.; Hallak, J.E.C.; Zuardi, A.W.; Crippa, J.A.; Dal-Pizzol, F. Evaluation of serum cytokines levels and the role of cannabidiol treatment in animal model of asthma. Mediat. Inflamm. 2015, 2015, 538670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuolo, F.; Abreu, S.C.; Michels, M.; Xisto, D.G.; Blanco, N.G.; Hallak, J.E.; Zuardi, A.W.; Crippa, J.A.; Reis, C.; Bahl, M.; et al. Cannabidiol reduces airway inflammation and fibrosis in experimental allergic asthma. Eur. J. Pharm. 2019, 843, 251–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hotta, M.; Nakata, R.; Katsukawa, M.; Hori, K.; Takahashi, S.; Inoue, H. Carvacrol, a component of thyme oil, activates PPARα and γ and suppresses COX-2 expression. J. Lipid Res. 2010, 51, 132–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciavarella, C.; Motta, I.; Valente, S.; Pasquinelli, G. Pharmacological (or synthetic) and nutritional agonists of PPAR-γ as candidates for cytokine storm modulation in COVID-19 disease. Molecules 2020, 25, 2076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suntres, Z.E.; Coccimiglio, J.; Alipour, M. The Bioactivity and toxicological actions of carvacrol. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2015, 55, 304–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beg, S.; Hasan, H.; Hussain, M.S.; Swain, S.; Barkat, M. Systematic review of herbals as potential anti-inflammatory agents: Recent advances, current clinical status and future perspectives. Phcog. Rev. 2011, 5, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karunaweera, N.; Raju, R.; Gyengesi, E.; Münch, G. Plant polyphenols as inhibitors of NF-kB induced cytokine production—A potential anti-inflammatory treatment for Alzheimer’s disease? Mol. Neurosci. 2015, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewlings, S.; Kalman, D. Curcumin: A review of its’ effects on human health. Foods 2017, 6, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchiani, A.; Rozzo, C.; Fadda, A.; Delogu, G.; Ruzza, P. Curcumin and curcumin-like molecules: From spice to drugs. Curr. Med. Chem. 2014, 21, 204–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noorafshan, A.; Ashkani-Esfahani, S. A Review of therapeutic effects of curcumin. Curr. Pharm. Des. 2013, 19, 2032–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohar, S.D.; Malik, S. The sirtuin system: The holy grail of resveratrol? J. Clin. Exp. Cardiol. 2012, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, O.; Wurglics, M.; Paulke, A.; Zitzkowski, J.; Meindl, N.; Bock, A.; Dingermann, T.; Abdel-Tawab, M.; Schubert-Zsilavecz, M. Carnosic acid and carnosol, phenolic diterpene compounds of the labiate herbs rosemary and sage, are activators of the human peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma. Planta Med. 2006, 72, 881–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasutto, L.; Mattarei, A.; Zoratti, M. Resveratrol and health: The starting point. ChemBioChem 2012, 13, 1256–1259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capiralla, H.; Vingtdeux, V.; Venkatesh, J.; Dreses-Werringloer, U.; Zhao, H.; Davies, P.; Marambaud, P. Identification of potent small-molecule inhibitors of STAT3 with anti-inflammatory properties in RAW 264.7 macrophages. FEBS J. 2012, 279, 3791–3799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.T.; Campos, K.M.; Cerqueira-Lima, A.T.; Cana Brasil Carneiro, T.; da Silva Velozo, E.; Ribeiro Melo, I.C.A.; Figueiredo, E.A.; de Jesus Oliveira, E.; de Vasconcelos, D.F.S.A.; Pontes-de-Carvalho, L.C.; et al. Potential therapeutic effect of Allium cepa L. and quercetin in a murine model of Blomia tropicalis induced asthma. Daru J. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kolehmainen, M.; Mykkänen, O.; Kirjavainen, P.V.; Leppänen, T.; Moilanen, E.; Adriaens, M.; Laaksonen, D.E.; Hallikainen, M.; Puupponen-Pimiä, R.; Pulkkinen, L.; et al. Bilberries reduce low-grade inflammation in individuals with features of metabolic syndrome. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2012, 56, 1501–1510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sengupta, R.; Sheorey, S.D.; Hinge, M.A. Analgesic and anti-inflammatory plants: An updated review. Int. J. Pharm. Sci. Rev. Res. 2012, 12, 114–119. [Google Scholar]

- Woranam, K.; Senawong, G.; Utaiwat, S.; Yunchalard, S.; Sattayasai, J.; Senawong, T. Anti-inflammatory activity of the dietary supplement Houttuynia cordata fermentation product in RAW264.7 cells and Wistar rats. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0230645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Speciale, A.; Chirafisi, J.; Cimino, F. Nutritional antioxidants and adaptive cell responses: An update. Curr. Mol. Med. 2011, 11, 770–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panahi, Y.; Hosseini, M.S.; Khalili, N.; Naimi, E.; Simental-Mendía, L.E.; Majeed, M.; Sahebkar, A. Effects of curcumin on serum cytokine concentrations in subjects with metabolic syndrome: A post-hoc analysis of a randomized controlled trial. Biomed. Pharm. 2016, 82, 578–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Drummond, E.M.; Harbourne, N.; Marete, E.; Martyn, D.; Jacquier, J.; O’Riordan, D.; Gibney, E.R. Inhibition of proinflammatory biomarkers in THP1 macrophages by polyphenols derived from chamomile, meadowsweet and willow bark: Antiinflammatory polyphenols from herbs. Phytother. Res. 2013, 27, 588–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.C.; Prasad, S.; Kim, J.H.; Patchva, S.; Webb, L.J.; Priyadarsini, I.K.; Aggarwal, B.B. Multitargeting by curcumin as revealed by molecular interaction studies. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2011, 28, 1937. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The members of the SOLOS Investigators; Fitó, M.; Cladellas, M.; de la Torre, R.; Martí, J.; Muñoz, D.; Schröder, H.; Alcántara, M.; Pujadas-Bastardes, M.; Marrugat, J.; et al. Anti-inflammatory effect of virgin olive oil in stable coronary disease patients: A randomized, crossover, controlled trial. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 62, 570–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aravindaram, K.; Yang, N.-S. Anti-inflammatory plant natural products for cancer therapy. Planta Med. 2010, 76, 1103–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyu, S.Y.; Park, W.B. Production of cytokine and NO by RAW 264.7 macrophages and PBMC in vitro incubation with flavonoids. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2005, 28, 573–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watzl, B. Anti-inflammatory effects of plant-based foods and of their constituents. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 2008, 78, 293–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, K.; Ping, S.; Huang, S.; Hu, L.; Xuan, H.; Zhang, C.; Hu, F. Molecular mechanisms underlying the In Vitro anti-inflammatory effects of a flavonoid-rich ethanol extract from chinese propolis (Poplar Type). Evid. Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2013, 2013, 127672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arreola, R.; Quintero-Fabián, S.; López-Roa, R.I.; Flores-Gutiérrez, E.O.; Reyes-Grajeda, J.P.; Carrera-Quintanar, L.; Ortuño-Sahagún, D. Immunomodulation and anti-inflammatory effects of garlic compounds. J. Immunol. Res. 2015, 2015, 401630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bose, S.; Laha, B.; Banerjee, S. Anti-inflammatory activity of isolated allicin from garlic with post-acoustic waves and microwave radiation. J. Od Adv. Pharm. Educ. Res. 2013, 3, 512–515. [Google Scholar]

- Costiniuk, C.T.; Jenabian, M.-A. Cannabinoids and inflammation: Implications for people living with HIV. AIDS 2019, 33, 2273–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galiegue, S.; Mary, S.; Marchand, J.; Dussossoy, D.; Carriere, D.; Carayon, P.; Bouaboula, M.; Shire, D.; Fur, G.; Casellas, P. Expression of central and peripheral cannabinoid receptors in human immune tissues and leukocyte subpopulations. Eur. J. Biochem. 1995, 232, 54–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarafian, T.; Montes, C.; Harui, A.; Beedanagari, S.; Kiertscher, S.; Stripecke, R.; Hossepian, D.; Kitchen, C.; Kern, R.; Belperio, J. Clarifying CB2 receptor-dependent and independent effects of THC on human lung epithelial cells. Toxicol. Appl. Pharm. 2008, 231, 282–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martín-Fontecha, M.; Angelina, A.; Rückert, B.; Rueda-Zubiaurre, A.; Martín-Cruz, L.; van de Veen, W.; Akdis, M.; Ortega-Gutiérrez, S.; López-Rodríguez, M.L.; Akdis, C.A.; et al. A fluorescent probe to unravel functional features of cannabinoid receptor CB 1 in human blood and tonsil immune system cells. Bioconjug. Chem. 2018, 29, 382–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, J.M.; Kaplan, B.L.F. Immune responses regulated by cannabidiol. Cannabis Cannabinoid Res. 2020, 5, 12–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abba, Y.; Hassim, H.; Hamzah, H.; Noordin, M.M. Antiviral activity of resveratrol against human and animal viruses. Adv. Virol. 2015, 2015, 184241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campagna, M.; Rivas, C. Antiviral activity of resveratrol. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2010, 38, 50–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vestergaard, M.; Ingmer, H. Antibacterial and antifungal properties of resveratrol. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2019, 53, 716–723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, S.-C.; Ho, C.-T.; Chuo, W.-H.; Li, S.; Wang, T.T.; Lin, C.-C. Effective inhibition of MERS-CoV infection by resveratrol. BMC Infect. Dis. 2017, 17, 144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lin, C.; Lin, H.-J.; Chen, T.-H.; Hsu, Y.-A.; Liu, C.-S.; Hwang, G.-Y.; Wan, L. Polygonum cuspidatum and its active components inhibit replication of the influenza virus through toll-like receptor 9-induced interferon beta expression. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mastromarino, P.; Capobianco, D.; Cannata, F.; Nardis, C.; Mattia, E.; De Leo, A.; Restignoli, R.; Francioso, A.; Mosca, L. Resveratrol inhibits rhinovirus replication and expression of inflammatory mediators in nasal epithelia. Antivir. Res. 2015, 123, 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palamara, A.T.; Nencioni, L.; Aquilano, K.; De Chiara, G.; Hernandez, L.; Cozzolino, F.; Ciriolo, M.R.; Garaci, E. Inhibition of influenza A virus replication by resveratrol. J. Infect. Dis 2005, 191, 1719–1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Zang, N.; Li, S.; Wang, L.; Deng, Y.; He, Y.; Yang, X.; Liu, E. Resveratrol inhibits respiratory syncytial virus-induced IL-6 production, decreases viral replication, and downregulates TRIF expression in airway epithelial cells. Inflammation 2012, 35, 1392–1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeung, M.-L.; Yao, Y.; Jia, L.; Chan, J.F.W.; Chan, K.-H.; Cheung, K.-F.; Chen, H.; Poon, V.K.M.; Tsang, A.K.L.; To, K.K.W.; et al. MERS coronavirus induces apoptosis in kidney and lung by upregulating Smad7 and Fgf2. Nat. Microbiol. 2016, 1, 16004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Chu, H.; Li, C.; Wong, B.H.-Y.; Cheng, Z.-S.; Poon, V.K.-M.; Sun, T.; Lau, C.C.-Y.; Wong, K.K.-Y.; Chan, J.Y.-W.; et al. Active replication of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus and aberrant induction of inflammatory cytokines and chemokines in human macrophages: Implications for pathogenesis. J. Infect. Dis. 2014, 209, 1331–1342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miraglia Del Giudice, M.; Maiello, N.; Decimo, F.; Capasso, M.; Campana, G.; Leonardi, S.; Ciprandi, G. Resveratrol plus carboxymethyl-β-glucan may affect respiratory infections in children with allergic rhinitis. Pediatr. Allergy Immunol. 2014, 25, 724–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, W.; Yu, H.; Huang, S.; Zhu, P. Resveratrol protects against TNF-α-induced injury in human umbilical endothelial cells through promoting sirtuin-1-induced repression of NF-KB and p38 MAPK. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baldassarre, M.E.; Di Mauro, A.; Labellarte, G.; Pignatelli, M.; Fanelli, M.; Schiavi, E.; Mastromarino, P.; Capozza, M.; Panza, R.; Laforgia, N. Resveratrol plus carboxymethyl-β-glucan in infants with common cold: A randomized double-blind trial. Heliyon 2020, 6, e03814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varricchio, A.M.; Capasso, M.; della Volpe, A.; Malafronte, L.; Mansi, N.; Varricchio, A.; Ciprandi, G. Resveratrol plus carboxymethyl-β-glucan in children with recurrent respiratory infections: A preliminary and real-life experience. Ital. J. Pediatr. 2014, 40, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]