Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Giustino Varrassi | -- | 2055 | 2025-09-25 10:11:38 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 2055 | 2025-09-25 10:33:19 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Al Sharie, S.; Varga, S.J.; Al-Husinat, L.; Sarzi-Puttini, P.; Araydah, M.; Bal’awi, B.R.; Varrassi, G. Unraveling the Complex Web of Fibromyalgia. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/59060 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Al Sharie S, Varga SJ, Al-Husinat L, Sarzi-Puttini P, Araydah M, Bal’awi BR, et al. Unraveling the Complex Web of Fibromyalgia. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/59060. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Al Sharie, Sarah, Scott J. Varga, Lou’i Al-Husinat, Piercarlo Sarzi-Puttini, Mohammad Araydah, Batool Riyad Bal’awi, Giustino Varrassi. "Unraveling the Complex Web of Fibromyalgia" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/59060 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Al Sharie, S., Varga, S.J., Al-Husinat, L., Sarzi-Puttini, P., Araydah, M., Bal’awi, B.R., & Varrassi, G. (2025, September 25). Unraveling the Complex Web of Fibromyalgia. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/59060

Al Sharie, Sarah, et al. "Unraveling the Complex Web of Fibromyalgia." Encyclopedia. Web. 25 September, 2025.

Copy Citation

Fibromyalgia is a complex and often misunderstood chronic pain disorder. It is characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, and heightened sensitivity, and has evolved in diagnostic criteria and understanding over the years. Initially met with skepticism, fibromyalgia is now recognized as a global health concern affecting millions of people, with a prevalence transcending demographic boundaries.

fibromyalgia

chronic pain

diagnosis

management

1. Introduction

Fibromyalgia, a term coined in the early 1970s, represents a complex and challenging clinical entity that extends beyond the boundaries of traditional medical classifications [1]. In the realm of chronic pain disorders, fibromyalgia stands as a perplexing and often misunderstood condition, characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain, tenderness, and a constellation of associated symptoms [2].

At its core, fibromyalgia is a chronic pain syndrome characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, sleep disturbances, and heightened sensitivity to tactile stimuli [3]. One of the hallmark features is the presence of tender points on the body, as defined by the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) [4]. However, the understanding of fibromyalgia has transcended a mere constellation of symptoms; it encompasses a broader spectrum of physiological and psychological intricacies [5].

The definition of fibromyalgia has undergone notable revisions over the years, reflecting the evolving understanding of the condition [6]. Initially perceived primarily as a rheumatic disorder, it is now recognized as a disorder of pain processing and central nervous system sensitization [6][7]. The diagnostic criteria have shifted from reliance solely on tender points to a more comprehensive evaluation, considering the widespread nature of pain and associated symptoms [8].

The concept of fibromyalgia can be traced back to the early 19th century when physicians described a condition known as muscular rheumatism [1]. However, it was not until the late 20th century that fibromyalgia emerged as a distinct entity. In 1990, the ACR introduced the first set of classification criteria, formalizing fibromyalgia as a recognized medical condition [9].

Historically, fibromyalgia was often met with skepticism within the medical community, with some dismissing it as a psychosomatic disorder [10]. This skepticism, rooted in a lack of objective diagnostic markers, hindered the acknowledgment and understanding of fibromyalgia [10]. Over time, however, advancements in research and a growing body of evidence have elucidated the complex interplay of biological, psychological, and social factors contributing to the syndrome [11][12].

Once considered a rare and enigmatic condition, fibromyalgia has gained recognition as a prevalent health concern on a global scale [13]. Epidemiological studies reveal a staggering prevalence, with estimates suggesting that millions of individuals worldwide are affected by fibromyalgia [14]. The prevalence is not confined to a specific demographic, transcending age, gender, and socio-economic status [14].

The epidemiology of fibromyalgia paints a nuanced picture, showcasing its impact on diverse populations [15]. Women are disproportionately affected, with a prevalence several times higher than that in men [16]. The condition often manifests during middle adulthood, although it can affect individuals of any age, including adolescents and the elderly [17].

2. Clinical Features and Diagnosis

Fibromyalgia presents a clinical panorama marked by a myriad of symptoms, often making the diagnosis a complex process that requires a comprehensive evaluation of the patient’s medical history, physical examination, and consideration of associated factors [18][19][20].

The hallmark symptom of fibromyalgia is widespread, chronic musculoskeletal pain. Pain is typically present on both sides of the body, above and below the waist, and along the spine [21][22]. The pain is often described as a deep, persistent ache and may vary in intensity [22]. Patients commonly experience profound fatigue, regardless of the quantity or quality of sleep [23].

Sleep disturbances are pervasive in patients affected by fibromyalgia. They frequently report difficulties falling asleep, staying asleep, or experiencing restorative sleep [24]. These disturbances contribute to the cycle of pain and fatigue [24].

Many individuals with fibromyalgia report cognitive difficulties, often referred to as “fibro fog”. This includes problems with concentration, memory, and the ability to perform mental tasks [25]. Moreover, fatigue accounts for one of the most common symptoms of fibromyalgia [26].

The presence of tender points is a characteristic feature, although it is no longer the sole criterion for diagnosis [27]. These tender points are specific anatomical sites where pressure elicits pain [27]. Historically, the ACR defined 18 tender points symmetrically distributed across the body; however, the diagnostic approach has evolved to encompass a more holistic evaluation [28].

Patients may also experience a range of other symptoms, including headaches, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), temporomandibular joint (TMJ) disorders, anxiety, and depression [29][30][31].

The diagnosis of fibromyalgia has evolved from the initial emphasis on tender points to a more comprehensive and inclusive approach [6]. The ACR has updated its diagnostic criteria to better capture the diverse manifestations of fibromyalgia [32]. The current criteria, established in 2010, include:

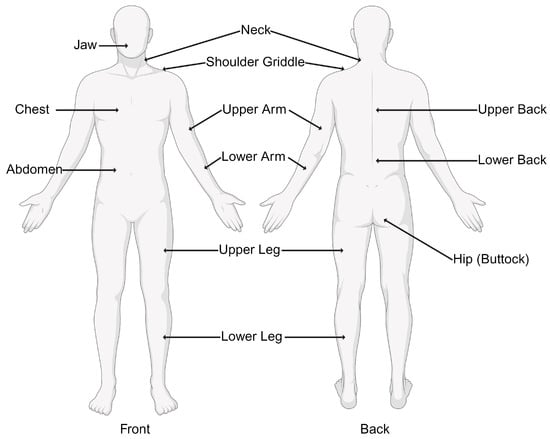

1. Widespread Pain Index (WPI): This involves assessing pain in 19 specified body areas over the past week. The areas include the neck, shoulders, chest, arms, lower back, hips, and legs. Figure 1 demonstrates the 19 specific tender points used in the diagnosis of fibromyalgia.

Figure 1. Nineteen tender points used by the Widespread Pain Index (WPI) in the diagnosis of fibromyalgia.

- 2.

-

Symptom severity (SS) score: In addition to the WPI, the SS score considers the severity of other symptoms such as fatigue, sleep disturbances, and cognitive difficulties. Table 1 demonstrates SS score calculation variables.Table 1. Symptom severity score calculation variables.

No Problem Mild Moderate Severe Fatigue 0 1 2 3 Trouble thinking or remembering 0 1 2 3 Waking up tired (unrefreshed) 0 1 2 3

To meet the diagnostic criteria, a patient must have widespread pain (WPI ≥ 7) and SS score ≥ 5 or WPI of 3–6 and SS score ≥ 9 (29).

3. Differential Diagnosis

Given the overlapping nature of symptoms, fibromyalgia can be challenging to distinguish from other conditions [33]. A thorough differential diagnosis is essential to rule out similar disorders, including rheumatoid arthritis (RA), systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE), and inflammatory arthritis, which present with joint pain and stiffness that can mimic fibromyalgia symptoms, but their inflammatory nature is what sets it apart [34]. Moreover, chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS) can be distinguished by the fact that, unlike fibromyalgia, CFS is primarily characterized by profound fatigue and post-exertional malaise [35]. Furthermore, hypothyroidism can cause fatigue and musculoskeletal pain, resembling fibromyalgia symptoms which can be excluded by a thorough thyroid investigation [36].

Accurate diagnosis involves a thorough evaluation by a healthcare professional, often a rheumatologist, who considers the patient’s symptoms and medical history and excludes other potential causes of pain and fatigue [37]. A multidimensional approach to diagnosis ensures a more accurate and nuanced understanding of fibromyalgia in the context of an individual’s overall health [38].

4. Etiology and Pathophysiology

Fibromyalgia’s etiology and pathophysiology are intricate and multifaceted, involving a complex interplay of genetic, neurological, and immunological factors [18]. While the precise mechanisms remain incompletely understood, contemporary research has provided valuable insights into the contributors to the development and perpetuation of fibromyalgia [39].

4.1. Genetic Factors

Genetic predisposition plays a significant role in a person’s susceptibility to fibromyalgia [40]. Studies have identified specific genetic markers associated with an increased risk of developing the condition [41]. The heritability of fibromyalgia is estimated to be around 50%, indicating a substantial genetic influence [42]. Variations in genes involved in pain perception, neurotransmitter regulation, and immune function have been implicated [43].

The identification of genetic factors provides a foundation for understanding the hereditary nature of fibromyalgia, but it is important to recognize the interaction between genetics and environmental factors [40]. Environmental triggers, such as physical trauma, infections, or stressful life events, may act as catalysts in individuals with a genetic predisposition, contributing to the onset of fibromyalgia [44].

A study by D’Agnelli et al. [45] suggests that potential candidate genes associated with fibromyalgia include SLC64A4, TRPV2, MYT1L, and NRXN3 and that a gene–environment interaction, involving epigenetic alterations, has been proposed as a triggering mechanism. Moreover, they have demonstrated that fibromyalgia exhibits a hypomethylated DNA pattern in genes related to stress response, DNA repair, autonomic system response, and subcortical neuronal abnormalities.

4.2. Neurotransmitter Dysregulation

Neurotransmitter dysregulation is a central feature in the pathophysiology of fibromyalgia, impacting the processing of pain signals in the central nervous system [46]. Several neurotransmitters, including serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine, are implicated in the altered pain perception observed in fibromyalgia patients [46].

Low levels of serotonin have been consistently observed in fibromyalgia [46]. A case–control study focusing on fibromyalgia involved 35 healthy women (Group I) as controls and 130 women with fibromyalgia (Group II) [47]. The study found a significantly lower serum serotonin level in fibromyalgia patients compared to healthy individuals and a positive significant correlation was observed between serotonin levels and tender points in fibromyalgia patients, suggesting associations between fibromyalgia and certain demographic factors, hematological platelet indices, and serotonin levels.

Moreover, the dysregulation of norepinephrine, which plays a role in the body’s stress response and pain modulation, is also evident in fibromyalgia [48]. This dysregulation may contribute to the heightened sensitivity to pain and the characteristic fatigue experienced by fibromyalgia patients [48].

A prospective double-blind controlled study involving 20 fibromyalgia patients, 20 rheumatoid arthritis patients, and 20 healthy controls aimed to assess norepinephrine-evoked pain by injecting norepinephrine and a placebo (saline solution) into separate forearms [49]. The study showed that 80% of fibromyalgia patients experienced norepinephrine-evoked pain, compared to 30% of rheumatoid arthritis patients and 30% of healthy controls. The intensity of norepinephrine-evoked pain was significantly greater in fibromyalgia patients (2.5 ± 2.5) compared to rheumatoid arthritis patients (0.3 ± 0.7) and healthy controls (0.3 ± 0.8) with a p-value less than 0.0001 suggesting that fibromyalgia patients exhibit heightened sensitivity to norepinephrine-induced pain compared to the other groups studied [49].

Also, dopamine has been implicated in the emotional aspects of fibromyalgia as the dysregulation of dopamine pathways may contribute to the mood disorders often observed in fibromyalgia patients [50]. The findings of a study suggest that fibromyalgia patients experience disrupted release of endogenous dopamine in response to both experimental pain and nonpainful stimulation in the basal ganglia [51]. This dysfunction in dopaminergic neurotransmission may explain the main clinical symptoms of fibromyalgia, e.g., widespread pain and bodily tenderness. It also raises the possibility that other symptoms of fibromyalgia may also result from this abnormality [51].

4.3. Central Sensitization

Central sensitization is a key concept in understanding the amplification of pain signals in fibromyalgia [52]. It involves an abnormal response of the central nervous system to stimuli, leading to an exaggerated and prolonged pain experience [53].

It is linked to alterations in the function of N-methyl-D-aspartate (NMDA) receptors and an imbalance in excitatory and inhibitory neurotransmitter systems [54]. This phenomenon contributes to the widespread and persistent pain experienced by individuals with fibromyalgia [53].

4.4. Immune System Involvement

Emerging evidence suggests that immune system dysregulation and abnormalities in immune function, including increased levels of inflammatory cytokines, may contribute to the pathophysiology of fibromyalgia [55]. A study discussed the reduced immune system responsiveness in fibromyalgia and compared the two groups [55]. The characteristics of the fibromyalgia group included higher pain levels, greater fatigue, lower quality of life, and a higher prevalence of depression. It also exhibited altered responses to nociceptive tests. Moreover, the study analyzed monocyte characteristics and peripheral blood mononuclear cell (PBMC) responses after stimulation. The fibromyalgia group showed differences in the percentage of cells with monocytic properties, particularly under unstimulated conditions. Additionally, there were variations in CD14 and CD16 cell percentages and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) after stimulation. PBMC cultures from both groups exhibited a similar capacity to secrete IL-6 and IL-10 after stimulation, with a tendency for a lower stimulation index for IL-6 in the fibromyalgia group. B-cell and T-cell characteristics were also examined, revealing lower percentages of CD19+ B-cells in the fibromyalgia group. Both groups responded similarly to stimulation, with an increase in CD69+ cells. The study also investigated cytokine secretion related to T-helper subsets and T-cytotoxic cells, finding lower stimulation indices for IFN-γ in the fibromyalgia group. Correlation analysis revealed a negative correlation between the IFN-γ stimulation index and the cold pain threshold in the fibromyalgia group.

4.5. Oxidative Stress

Oxidative stress has been explored as a potential contributor to the pathophysiology of fibromyalgia [56]. Mitochondrial dysfunction, evident in increased ROS production, has been associated with fibromyalgia, suggesting a role for disrupted energy metabolism [57]. Additionally, oxidative stress may contribute to the heightened pain sensitivity characteristic of fibromyalgia by activating nociceptive neurons and impacting pain pathways [56]. The antioxidant defenses in fibromyalgia patients may be compromised, as evidenced by lower levels of antioxidants, further exacerbating oxidative stress [58]. The influence of oxidative stress on neurotransmitter systems implicated in pain perception and mood regulation adds another layer to the complex nature of fibromyalgia [58].

A study by Coppens et al. investigated the response of fibromyalgia patients to stress. It focused on cortisol levels and subjective stress in response to the Trier Social Stress Test (TSST), considering the influence of early childhood adversities (ECA). Key findings included fibromyalgia patients showing blunted cortisol responsivity to stress compared to controls, especially when ECA was accounted for [59].

References

- Inanici, F.; Yunus, M.B. History of fibromyalgia: Past to present. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2004, 8, 369–378.

- Goldenberg, D.L.; Bradley, L.A.; Arnold, L.M.; Glass, J.M.; Clauw, D.J. Understanding fibromyalgia and its related disorders. Prim. Care Companion J. Clin. Psychiatry 2008, 10, 133–144.

- Wood, P.B. Fibromyalgia. In Encyclopedia of Stress, 2nd ed.; Fink, G., Ed.; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 56–62.

- Wolfe, F.; Smythe, H.A.; Yunus, M.B.; Bennett, R.M.; Bombardier, C.; Goldenberg, D.L.; Tugwell, P.; Campbell, S.M.; Abeles, M.; Clark, P.; et al. The American College of Rheumatology 1990 Criteria for the Classification of Fibromyalgia. Report of the Multicenter Criteria Committee. Arthritis Rheum. 1990, 33, 160–172.

- Galvez-Sánchez, C.M.; Duschek, S.; Reyes Del Paso, G.A. Psychological impact of fibromyalgia: Current perspectives. Psychol. Res. Behav. Manag. 2019, 12, 117–127.

- Wolfe, F.; Rasker, J.J. The Evolution of Fibromyalgia, Its Concepts, and Criteria. Cureus 2021, 13, e20010.

- Woolf, C.J. Central sensitization: Implications for the diagnosis and treatment of pain. Pain 2011, 152, S2–S15.

- Bidari, A.; Ghavidel Parsa, B.; Ghalehbaghi, B. Challenges in fibromyalgia diagnosis: From meaning of symptoms to fibromyalgia labeling. Korean J. Pain 2018, 31, 147–154.

- Ahmed, S.; Aggarwal, A.; Lawrence, A. Performance of the American College of Rheumatology 2016 criteria for fibromyalgia in a referral care setting. Rheumatol. Int. 2019, 39, 1397–1403.

- Häuser, W.; Burgmer, M.; Köllner, V.; Schaefert, R.; Eich, W.; Hausteiner-Wiehle, C.; Henningsen, P. Fibromyalgia syndrome as a psychosomatic disorder—Diagnosis and therapy according to current evidence-based guidelines. Z. Psychosom. Med. Psychother. 2013, 59, 132–152.

- Dizner-Golab, A.; Lisowska, B.; Kosson, D. Fibromyalgia—Etiology, diagnosis and treatment including perioperative management in patients with fibromyalgia. Reumatologia 2023, 61, 137–148.

- Nicholas, M.; Vlaeyen, J.W.S.; Rief, W.; Barke, A.; Aziz, Q.; Benoliel, R.; Cohen, M.; Evers, S.; Giamberardino, M.A.; Goebel, A.; et al. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: Chronic primary pain. Pain 2019, 160, 28–37.

- Kwiatkowska, B.; Amital, H. Diagnostic and therapeutic challenge-fibromyalgia. Reumatologia 2018, 56, 273–274.

- Wolfe, F.; Walitt, B.; Perrot, S.; Rasker, J.J.; Häuser, W. Fibromyalgia diagnosis and biased assessment: Sex, prevalence and bias. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0203755.

- Neumann, L.; Buskila, D. Epidemiology of fibromyalgia. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2003, 7, 362–368.

- Arout, C.A.; Sofuoglu, M.; Bastian, L.A.; Rosenheck, R.A. Gender Differences in the Prevalence of Fibromyalgia and in Concomitant Medical and Psychiatric Disorders: A National Veterans Health Administration Study. J. Womens Health 2018, 27, 1035–1044.

- Taylor, S.; Furness, P.; Ashe, S.; Haywood-Small, S.; Lawson, K. Comorbid Conditions, Mental Health and Cognitive Functions in Adults with Fibromyalgia. West J. Nurs. Res. 2021, 43, 115–122.

- Siracusa, R.; Paola, R.D.; Cuzzocrea, S.; Impellizzeri, D. Fibromyalgia: Pathogenesis, Mechanisms, Diagnosis and Treatment Options Update. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3891.

- Varrassi, G.; Rekatsina, M.; Perrot, S.; Bouajina, E.; Paladini, A.; Coaccioli, S.; Narvaez Tamayo, M.A.; Sarzi Puttini, P. Is Fibromyalgia a Fashionable Diagnosis or a Medical Mystery? Cureus 2023, 15, e44852.

- Sarzi-Puttini, P.; Giorgi, V.; Atzeni, F.; Gorla, R.; Kosek, E.; Choy, E.H.; Bazzichi, L.; Häuser, W.; Ablin, J.N.; Aloush, V.; et al. Diagnostic and therapeutic care pathway for fibromyalgia. Clin. Exp. Rheumatol. 2021, 39 (Suppl. S130), 120–127.

- Perrot, S. Fibromyalgia syndrome: A relevant recent construction of an ancient condition? Curr. Opin. Support. Palliat. Care 2008, 2, 122–127.

- Culpepper, L. Evaluating the patient with fibromyalgia. J. Clin. Psychiatry 2010, 71, e25.

- Climent-Sanz, C.; Morera-Amenós, G.; Bellon, F.; Pastells-Peiró, R.; Blanco-Blanco, J.; Valenzuela-Pascual, F.; Gea-Sánchez, M. Poor Sleep Quality Experience and Self-Management Strategies in Fibromyalgia: A Qualitative Metasynthesis. J. Clin. Med. 2020, 9, 4000.

- Bigatti, S.M.; Hernandez, A.M.; Cronan, T.A.; Rand, K.L. Sleep disturbances in fibromyalgia syndrome: Relationship to pain and depression. Arthritis Rheum. 2008, 59, 961–967.

- Galvez-Sánchez, C.M.; Reyes Del Paso, G.A.; Duschek, S. Cognitive Impairments in Fibromyalgia Syndrome: Associations with Positive and Negative Affect, Alexithymia, Pain Catastrophizing and Self-Esteem. Front. Psychol. 2018, 9, 377.

- Thierheimer, M.; Cioffi, G.; Waite, K.A.; Kruchko, C.; Ostrom, Q.T.; Barnholtz-Sloan, J.S. Mortality trends in primary malignant brain and central nervous system tumors vary by histopathology, age, race, and sex. J. Neurooncol. 2023, 162, 167–177.

- Fitzcharles, M.A.; Yunus, M.B. The clinical concept of fibromyalgia as a changing paradigm in the past 20 years. Pain Res. Treat. 2012, 2012, 184835.

- Kim, S.M.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, H.R. Applying the ACR Preliminary Diagnostic Criteria in the Diagnosis and Assessment of Fibromyalgia. Korean J. Pain 2012, 25, 173–182.

- Garofalo, C.; Cristiani, C.M.; Ilari, S.; Passacatini, L.C.; Malafoglia, V.; Viglietto, G.; Maiuolo, J.; Oppedisano, F.; Palma, E.; Tomino, C.; et al. Fibromyalgia and Irritable Bowel Syndrome Interaction: A Possible Role for Gut Microbiota and Gut-Brain Axis. Biomedicines 2023, 11, 1701.

- Gui, M.S.; Pimentel, M.J.; Rizzatti-Barbosa, C.M. Temporomandibular disorders in fibromyalgia syndrome: A short-communication. Rev. Bras. Reumatol. 2015, 55, 189–194.

- Cetingok, S.; Seker, O.; Cetingok, H. The relationship between fibromyalgia and depression, anxiety, anxiety sensitivity, fear avoidance beliefs, and quality of life in female patients. Medicine 2022, 101, e30868.

- Wolfe, F.; Clauw, D.J.; Fitzcharles, M.A.; Goldenberg, D.L.; Katz, R.S.; Mease, P.; Russell, A.S.; Russell, I.J.; Winfield, J.B.; Yunus, M.B. The American College of Rheumatology preliminary diagnostic criteria for fibromyalgia and measurement of symptom severity. Arthritis Care Res. 2010, 62, 600–610.

- Qureshi, A.G.; Jha, S.K.; Iskander, J.; Avanthika, C.; Jhaveri, S.; Patel, V.H.; Rasagna Potini, B.; Talha Azam, A. Diagnostic Challenges and Management of Fibromyalgia. Cureus 2021, 13, e18692.

- Pineda-Sic, R.A.; Vega-Morales, D.; Santoyo-Fexas, L.; Garza-Elizondo, M.A.; Mendiola-Jiménez, A.; González Marquez, K.I.; Carrillo-Haro, B. Are the cut-offs of the rheumatoid factor and anti-cyclic citrullinated peptide antibody different to distinguish rheumatoid arthritis from their primary differential diagnoses? Int. J. Immunogenet. 2023, 51, 1–9.

- Stussman, B.; Williams, A.; Snow, J.; Gavin, A.; Scott, R.; Nath, A.; Walitt, B. Characterization of Post-exertional Malaise in Patients with Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Front. Neurol. 2020, 11, 1025.

- Fischer, S.; Markert, C.; Strahler, J.; Doerr, J.M.; Skoluda, N.; Kappert, M.; Nater, U.M. Thyroid Functioning and Fatigue in Women with Functional Somatic Syndromes—Role of Early Life Adversity. Front. Physiol. 2018, 9, 564.

- McManimen, S.L.; Jason, L.A. Post-Exertional Malaise in Patients with ME and CFS with Comorbid Fibromyalgia. SRL Neurol. Neurosurg. 2017, 3, 22–27.

- Hackshaw, K. Assessing our approach to diagnosing Fibromyalgia. Expert Rev. Mol. Diagn. 2020, 20, 1171–1181.

- Schmidt-Wilcke, T.; Diers, M. New Insights into the Pathophysiology and Treatment of Fibromyalgia. Biomedicines 2017, 5, 22.

- Park, D.J.; Lee, S.S. New insights into the genetics of fibromyalgia. Korean J. Intern. Med. 2017, 32, 984–995.

- Shukla, H.; Mason, J.L.; Sabyah, A. Identifying genetic markers associated with susceptibility to cardiovascular diseases. Future Sci. OA 2019, 5, Fso350.

- Dutta, D.; Brummett, C.M.; Moser, S.E.; Fritsche, L.G.; Tsodikov, A.; Lee, S.; Clauw, D.J.; Scott, L.J. Heritability of the Fibromyalgia Phenotype Varies by Age. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020, 72, 815–823.

- van Reij, R.R.I.; Joosten, E.A.J.; van den Hoogen, N.J. Dopaminergic neurotransmission and genetic variation in chronification of post-surgical pain. Br. J. Anaesth. 2019, 123, 853–864.

- Bradley, L.A. Pathophysiology of fibromyalgia. Am. J. Med. 2009, 122, S22–S30.

- D’Agnelli, S.; Arendt-Nielsen, L.; Gerra, M.C.; Zatorri, K.; Boggiani, L.; Baciarello, M.; Bignami, E. Fibromyalgia: Genetics and epigenetics insights may provide the basis for the development of diagnostic biomarkers. Mol. Pain 2019, 15, 1744806918819944.

- Becker, S.; Schweinhardt, P. Dysfunctional neurotransmitter systems in fibromyalgia, their role in central stress circuitry and pharmacological actions on these systems. Pain Res. Treat. 2012, 2012, 741746.

- Al-Nimer, M.S.M.; Mohammad, T.A.M.; Alsakeni, R.A. Serum levels of serotonin as a biomarker of newly diagnosed fibromyalgia in women: Its relation to the platelet indices. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2018, 23, 71.

- Ali, Z.; Raja, S.N.; Wesselmann, U.; Fuchs, P.N.; Meyer, R.A.; Campbell, J.N. Intradermal injection of norepinephrine evokes pain in patients with sympathetically maintained pain. Pain 2000, 88, 161–168.

- Martinez-Lavin, M.; Vidal, M.; Barbosa, R.E.; Pineda, C.; Casanova, J.M.; Nava, A. Norepinephrine-evoked pain in fibromyalgia. A randomized pilot study . BMC Musculoskelet. Disord. 2002, 3, 2.

- Albrecht, D.S.; MacKie, P.J.; Kareken, D.A.; Hutchins, G.D.; Chumin, E.J.; Christian, B.T.; Yoder, K.K. Differential dopamine function in fibromyalgia. Brain Imaging Behav. 2016, 10, 829–839.

- Wood, P.B.; Schweinhardt, P.; Jaeger, E.; Dagher, A.; Hakyemez, H.; Rabiner, E.A.; Bushnell, M.C.; Chizh, B.A. Fibromyalgia patients show an abnormal dopamine response to pain. Eur. J. Neurosci. 2007, 25, 3576–3582.

- Smeets, Y.; Soer, R.; Chatziantoniou, E.; Preuper, R.; Reneman, M.F.; Wolff, A.P.; Timmerman, H. Role of non-invasive objective markers for the rehabilitative diagnosis of central sensitization in patients with fibromyalgia: A systematic review. J. Back Musculoskelet. Rehabil. 2023.

- Latremoliere, A.; Woolf, C.J. Central sensitization: A generator of pain hypersensitivity by central neural plasticity. J. Pain 2009, 10, 895–926.

- Liu, Y.J.; Li, Y.L.; Fang, Z.H.; Liao, H.L.; Zhang, Y.Y.; Lin, J.; Liu, F.; Shen, J.F. NMDARs mediate peripheral and central sensitization contributing to chronic orofacial pain. Front. Cell. Neurosci. 2022, 16, 999509.

- Björkander, S.; Ernberg, M.; Bileviciute-Ljungar, I. Reduced immune system responsiveness in fibromyalgia—A pilot study. Clin. Immunol. Commun. 2022, 2, 46–53.

- Rekatsina, M.; Paladini, A.; Piroli, A.; Zis, P.; Pergolizzi, J.V.; Varrassi, G. Pathophysiology and Therapeutic Perspectives of Oxidative Stress and Neurodegenerative Diseases: A Narrative Review. Adv. Ther. 2020, 37, 113–139.

- Cordero, M.D.; de Miguel, M.; Carmona-López, I.; Bonal, P.; Campa, F.; Moreno-Fernández, A.M. Oxidative stress and mitochondrial dysfunction in fibromyalgia. Neuro Endocrinol. Lett. 2010, 31, 169–173.

- Assavarittirong, C.; Samborski, W.; Grygiel-Górniak, B. Oxidative Stress in Fibromyalgia: From Pathology to Treatment. Oxid. Med. Cell. Longev. 2022, 2022, 1582432.

- Coppens, E.; Kempke, S.; Van Wambeke, P.; Claes, S.; Morlion, B.; Luyten, P.; Van Oudenhove, L. Cortisol and Subjective Stress Responses to Acute Psychosocial Stress in Fibromyalgia Patients and Control Participants. Psychosom. Med. 2018, 80, 317–326.

More

Information

Subjects:

Rheumatology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

96

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

25 Sep 2025

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No