| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ashraf M. Salama | -- | 1663 | 2025-09-08 04:38:54 | | | |

| 2 | Vicky Zhou | Meta information modification | 1663 | 2025-09-08 04:45:19 | | |

Video Upload Options

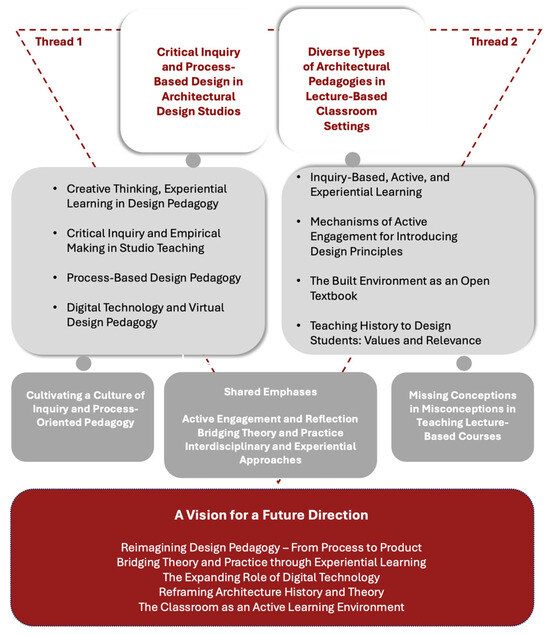

This entry is based on the premise that pressing issues of climate change, social injustice, and post-COVID practices appear to have superseded some essential values of architectural and design pedagogy, leading to improvements in content that may be offset by a loss of focus on the core curriculum. The entry reimagines architectural pedagogy by arguing for a transformative shift from traditional product-based education to a process-oriented, inquiry-driven approach that cultivates critical thinking and empirical making, predicated upon experiential learning. It aims to integrate rigorous critical inquiry into both studio-based and lecture-based settings, thus critiquing assumed limitations of conventional approaches that prioritise final outcomes over iterative design processes, dialogue, and active engagement. Employing a comprehensive qualitative approach that incorporates diverse case studies and critical reviews, the analysis is divided into two main threads: one that places emphasis on the studio environment and another that focuses on lecture-based courses. Within these threads, the analysis is structured around a series of key themes central to experiential learning, each of which concludes with a key message that synthesises the core insights derived from case studies. The two threads instigate the identification of aligned areas of emphasis which articulate the need for active engagements and reflection, for bridging theory and practice, and for adopting interdisciplinary and experiential approaches. Conclusions are drawn to establish guidance for a future direction of a strengthened and pedagogically enriched architectural education.

Rationale and Brief Argument

Objectives

-

Examine the role of critical inquiry, empirical making, and process-oriented approaches in architectural pedagogy.

-

Demonstrate how experiential learning and digital technologies can enhance studio teaching.

-

Explore approaches to encourage active engagement in lecture-based courses or taught modules.

-

Develop recommendations for cultivating a culture of inquiry and collaboration within the student body, and between students and staff.

Approach to Analysis

References

- Morin, E. Seven Complex Lessons in Education for the Future; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 1999.

- Jenkins, A.; Healey, M. Institutional Strategies to Link Teaching and Research; Higher Education Academy: York, UK, 2005; Available online: http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/assets/York/documents/ourwork/research/Institutional_strategies.pdf (accessed on 19 March 2025).

- Bose, M.; Pennypacker, E.; Yahner, T. Enhancing Critical Thinking through ‘Independent Decision-Making’ in the Studio. Open House Int. 2006, 31, 33–42.

- Burton, L.O.; Salama, A.M. Sustainable Development Goals and the Future of Architectural Education—Cultivating SDGs-Centred Architectural Pedagogies. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2023, 17, 421–442.

- Salama, A.M.; Burton, L.O. Pedagogical Traditions in Architecture: The Canonical, the Resistant, and the Decolonized. Tradit. Dwell. Settl. Rev. 2023, 35, 47–71.

- Kolb, D.A. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development; Prentice Hall: Englewood Cliffs, NJ, USA, 1984.

- Schön, D.A. The Reflective Practitioner; Jossey-Bass: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1983.

- Salama, A.M. A Process Oriented Design Pedagogy: KFUPM Sophomore Studio. CEBE Trans. 2005, 2, 16–31.

- McAllister, K. The Design Process: Making It Relevant for Students. Archnet-IJAR Int. J. Archit. Res. 2010, 4, 76–89.

- UIA-EDUCOM. UNESCO-UIA Architectural Study Programme Validation. International Union of Architects. 2023. Available online: https://www.uia-architectes.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/FINAL_UNESCO-UIA_Validation_Manual_2023.pdf (accessed on 23 February 2025).

- Boyer, E.L.; Mitgang, L.D. Building Community: A New Guide for Architectural Education and Practice; Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1996. Available online: https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED399717.pdf (accessed on 1 March 2025).

- Koch, A.; Schwennsen, K.; Dutton, T.; Smith, D. The Redesign of Studio Culture. In Studio Culture Task Force; The American Institute of Architecture Students-AIAS: Washington, DC, USA, 2002; Available online: https://www.aias.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/09/The_Redesign_of_Studio_Culture_2002.pdf (accessed on 15 February 2025).

- AACA. National Standard of Competency for Architects; Architects Accreditation Council of Australia: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2021; Available online: https://aaca.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2021-NSCA.pdf (accessed on 22 February 2025).

- AACA. Architectural Practice Examination Overview; Architects Accreditation Council of Australia: Canberra, ACT, Australia, 2023; Available online: https://aaca.org.au/architectural-practice-examination/ (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- RIBA. 2030 Climate Challenge; Royal Institute of British Architects: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.architecture.com/about/policy/climate-action/2030-climate-challenge (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- RIBA. The Way Ahead—An Introduction to the New RIBA Education and Professional Development Framework and an Overview of Its Key Components; Royal Institute of British Architects: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.architecture.com/knowledge-and-resources/resources-landing-page/the-way-ahead (accessed on 2 March 2025).

- ACSA. Equity in Architectural Education; Association of Collegiate Schools of Architecture: Washington, DC, USA, 2023; Available online: https://www.acsa-arch.org/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Equity_in_Architectural_Education_Supplement.pdf (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- NAAB. Conditions for Accreditation and Procedures for Accreditation; National Architectural Accrediting Board: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.naab.org/accreditation/conditions-and-procedures/ (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- Salama, A.M. Spatial Design Education: New Directions for Pedagogy in Architecture and Beyond, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2016.

- Salama, A.M. Transformative Pedagogy in Architecture and Urbanism, 1st ed.; Routledge Revivals; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2021.

- Hadjiyanni, T. Integrating Social Science Research into Studio Teaching. Open House Int. 2006, 31, 60–66.

- Silva, K.D.; Fernando, N.A. (Eds.) Theorizing Built Form and Culture: The Legacy of Amos Rapoport, 1st ed.; Routledge Research in Architecture; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2023; pp. 235–246.

- Salama, A.M.; Osborne Burton, L. Defying a Legacy or an Evolving Process? A Post-Pandemic Architectural Design Pedagogy. Proc. ICE—Urban Des. Plan. 2022, 175, 5–21.

- Samuel, F.; Dye, A. Demystifying Architectural Research: Adding Value to Your Practice, 1st ed.; RIBA Publishing: London, UK, 2019.

- Groat, L.N.; Wang, D. Architectural Research Methods, 2nd ed.; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013.

- Lucas, R. Research Methods for Architecture; Laurence King Publishing: London, UK, 2016.