| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Stefanos Karapetis | -- | 979 | 2025-09-02 22:23:06 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | -76 word(s) | 958 | 2025-09-03 02:45:08 | | |

Video Upload Options

1. Introduction

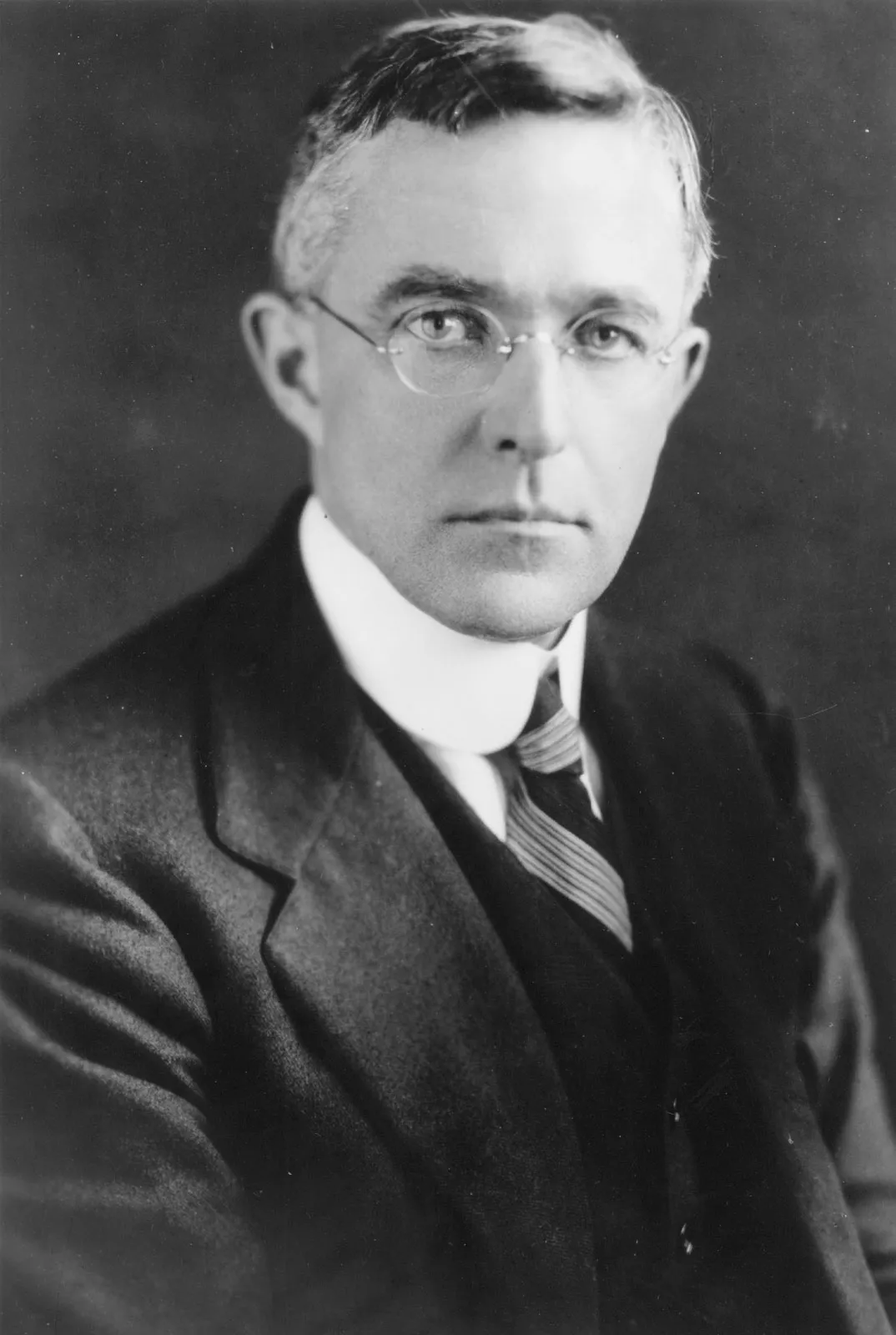

Irving Langmuir (1881–1957) was an American chemist and physicist whose groundbreaking work laid the foundation for modern surface science and membrane biophysics. He earned his undergraduate degree in metallurgical engineering from the Columbia University School of Mines and later obtained his doctorate from the University of Göttingen, Germany, under the mentorship of Walther Nernst (Perutz, 1987) [1][2][3][4].

Langmuir is best known for his contributions to surface chemistry, particularly his development of the Langmuir monolayer and Langmuir adsorption isotherm, which describe molecular behavior at interfaces. His 1917 paper, “The Constitution and Fundamental Properties of Solids and Liquids,” introduced a model for molecular adsorption that became fundamental in colloid and interface science (Langmuir, 1917). He later expanded this work to biological systems, establishing methods for studying lipid monolayers at the air–water interface, a concept still applied in the Langmuir-Blodgett technique for constructing artificial membranes (Adamson & Gast, 1997).

For his achievements, Langmuir was awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1932, “for his discoveries and investigations in surface chemistry” (Nobel Foundation, 1932). Beyond chemistry, his research influenced areas such as vacuum technology, electron emission, and plasma physics. Terms such as the Langmuir trough, Langmuir probe, and Langmuir waves remain standard in scientific literature, underscoring his lasting impact across disciplines.

Langmuir's career was largely spent at the General Electric Research Laboratory in Schenectady, New York, where he became the first industrial scientist to win a Nobel Prize. His work exemplifies the productive intersection of theoretical insight and applied science, shaping modern understandings of molecular interactions at interfaces.

Irving Langmuir's Education

-

Undergraduate Education

Langmuir earned a Bachelor of Science in Metallurgical Engineering from the Columbia University School of Mines in 1903. During this time, he developed a strong interest in physical chemistry and physics. -

Graduate Studies

After working briefly as an instructor and chemist, Langmuir pursued advanced studies in Germany. He studied under Walther Nernst at the University of Göttingen, one of the leading centers for physical chemistry at the time. There, he earned his Ph.D. in Chemistry in 1906 with a dissertation focused on dissociation phenomena in gases.

Langmuir’s education in both engineering and theoretical chemistry gave him a rare interdisciplinary foundation, enabling him to bridge industrial research and academic science throughout his career.

Irving Langmuir's Research Contributions

Irving Langmuir’s research spanned physical chemistry, surface science, plasma physics, and industrial chemistry. Below is a breakdown of his most influential contributions:

2. Surface Chemistry

-

Langmuir Monolayers

He developed a technique to study molecular films at the air–water interface. These monolayers were used to understand molecular orientation and packing density, forming the basis for the Langmuir-Blodgett film technique used in membrane and materials science. -

Langmuir Adsorption Isotherm (1916)

Langmuir formulated a mathematical model describing how molecules adsorb onto solid surfaces—a foundational equation in surface science and catalysis.

Key Paper: Langmuir, I. (1918). The adsorption of gases on plane surfaces of glass, mica and platinum. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 40(9), 1361–1403.

3. Plasma Physics and Electron Theory

-

Langmuir Probes:

Invented for measuring electron temperature and density in ionized gases (plasmas). Still used in plasma diagnostics today. -

Langmuir Waves:

He studied oscillations in plasma now known as Langmuir waves, foundational in astrophysics and space plasma research.

4. Chemical Bonding

-

Langmuir introduced the term "covalent bond" and refined Lewis’s electron pair theory, contributing to early models of molecular structure.

He proposed that atoms bond by sharing electron pairs—a concept later incorporated into quantum chemistry.

5. Vacuum Technology and Light Bulbs

-

While working at General Electric, Langmuir improved incandescent lamp efficiency by introducing inert gas (argon) and coiling tungsten filaments—technological advances that revolutionized lighting.

6. Atmospheric Science

-

Later in his career, he researched cloud seeding and weather modification, using silver iodide to induce rain—early steps in applied meteorology.

7. Legacy

Langmuir's interdisciplinary work made him one of the first true industrial scientists. His name lives on in terms such as:

-

Langmuir monolayer

-

Langmuir isotherm

-

Langmuir probe

-

Langmuir waves

-

Langmuir (the scientific journal)

He received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 1932 for his work in surface chemistry.

8. Personal Life of Irving Langmuir

Born: January 31, 1881, in Brooklyn, New York, USA

Died: August 16, 1957, in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, USA

Irving Langmuir was raised in a family that valued education and intellectual curiosity. His father, Charles Langmuir, was an insurance executive with a strong interest in science, which helped spark young Irving’s fascination with nature and experimentation .

Langmuir was known for his modesty, deep curiosity, and methodical thinking. He was not only a scientist but also an accomplished amateur mountaineer, photographer, and nature enthusiast. He often spent summers with his family in the Adirondacks, where he indulged his love for the outdoors and physical activity. He believed that personal experience in nature enhanced scientific creativity and clarity.

In 1912, Langmuir married Marian Mersereau, a former nurse. They had one son, Kenneth Langmuir. His family life was described as warm and supportive, and he remained devoted to his wife and son throughout his life.

Langmuir was also a skilled communicator and mentor, known for explaining complex ideas in accessible terms. His ability to move between theoretical concepts and practical applications made him a valued figure in both academic and industrial communities.

He spent most of his professional career at General Electric’s Research Laboratory in Schenectady, New York, where he was encouraged to pursue open-ended scientific inquiry—a rare freedom in industrial research at the time.

Langmuir passed away in 1957 at the age of 76, leaving behind a legacy of innovation, humility, and scientific excellence.

References

- Langmuir, I. (1917). The Constitution and Fundamental Properties of Solids and Liquids. Part I. Solids. Journal of the American Chemical Society, 39(9), 2221–2295. https://doi.org/10.1021/ja02254a006.

- Nobel Foundation. (1932). The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1932 – Irving Langmuir. Retrieved from https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/chemistry/1932/langmuir/biographical

- Adamson, A. W., & Gast, A. P. (1997). Physical Chemistry of Surfaces (6th ed.). Wiley-Interscience.

- Perutz, M. F. (1987). Irving Langmuir: Surface Chemistry and Beyond. Nature, 328(6129), 661–662. https://doi.org/10.1038/328661a0.

Location: Brooklyn, New York, U.S.