| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Encyclopedia Editorial Office | -- | 1001 | 2025-08-28 04:27:43 |

Video Upload Options

1. Introduction

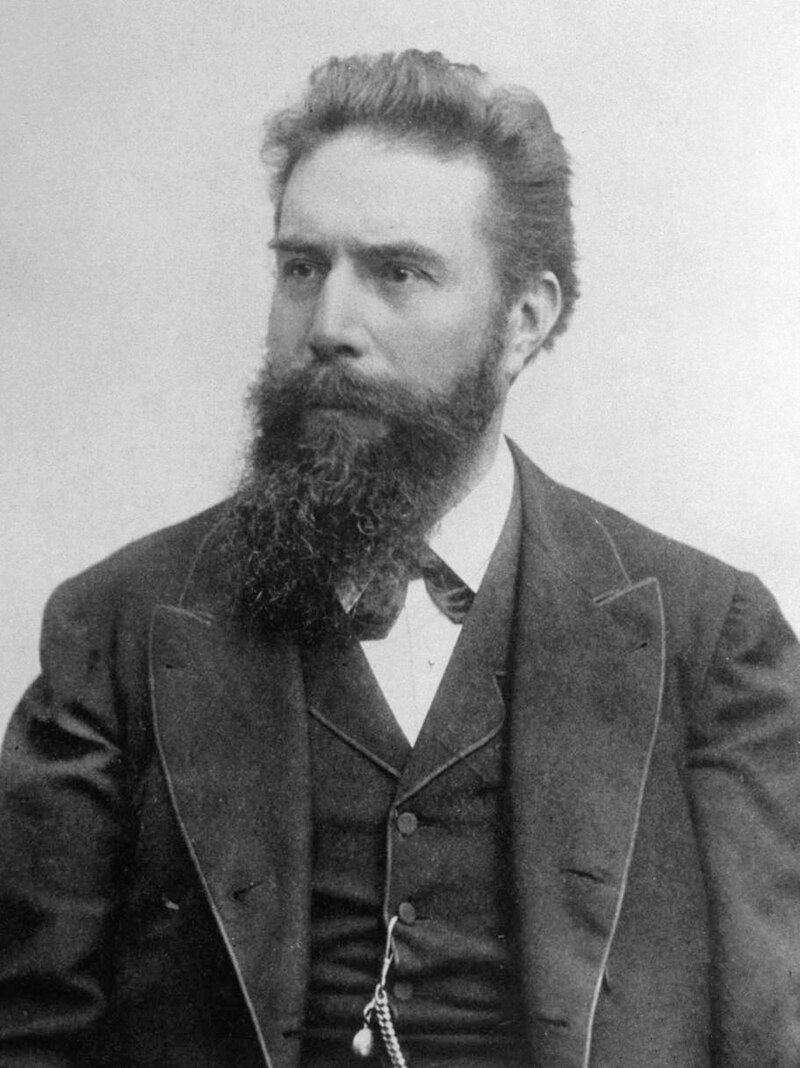

Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen (1845–1923) was a German physicist best known for his discovery of X-rays in 1895, a groundbreaking advancement in medical imaging and physics that revolutionized both science and medicine. He was the first recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1901 for this discovery. Röntgen’s contributions laid the foundation for diagnostic radiology and profoundly influenced twentieth-century medical practice and physical science.

2. Early Life and Education

Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen was born on March 27, 1845, in Lennep, Prussia (now part of Remscheid, Germany), into a family of cloth manufacturers [1]. In 1848, the family moved to Apeldoorn, the Netherlands, where Röntgen received much of his early education. His academic record in school was not exceptional, but he demonstrated a strong aptitude for mechanical work and an inventive spirit, often creating mechanical devices in his youth [2].

In 1865, Röntgen entered the Polytechnic School in Zurich (now ETH Zurich) after initially struggling to meet university entrance requirements. He studied mechanical engineering but was soon drawn toward physics, influenced by prominent figures such as August Kundt, with whom he would later work as an assistant. Röntgen received his Ph.D. in mechanical engineering from the University of Zurich in 1869, focusing on theoretical and experimental aspects of physics.

3. Academic Career

Following his doctorate, Röntgen worked as an assistant to Kundt at the University of Würzburg and later at the University of Strasbourg. His early work included investigations into the thermal conductivity of crystals and studies on specific heats. Röntgen’s academic career took him to various German universities, including Strasbourg, Giessen, and Würzburg, where he eventually became a full professor and director of the physics institute.

At the University of Würzburg, Röntgen established himself as a meticulous experimental physicist, known for his thoroughness, patience, and unwillingness to publish preliminary results. He cultivated a reputation for working in isolation, preferring careful repetition of experiments until results could be verified beyond doubt.

4. Discovery of X-rays

On November 8, 1895, while experimenting with cathode rays in a darkened laboratory at the University of Würzburg, Röntgen observed that a fluorescent screen coated with barium platinocyanide glowed despite being shielded from the direct path of the cathode rays by thick cardboard. This suggested the presence of an unknown penetrating radiation, which he initially termed “X-rays” to signify their mysterious nature.

Over the following weeks, Röntgen conducted systematic experiments to study the properties of these rays. He demonstrated their ability to penetrate various materials, their differential absorption depending on density, and most famously, their ability to produce images of bones within living tissue. The first X-ray image he produced was of his wife Anna Bertha’s hand, clearly showing the bones and her wedding ring. This iconic image, presented in December 1895, sparked immediate international attention.

Röntgen published his findings in his seminal paper “On a New Kind of Rays” (Über eine neue Art von Strahlen) in late 1895, which was rapidly disseminated across scientific communities worldwide. His discovery was hailed as one of the most significant scientific achievements of the nineteenth century.

5. Scientific Contributions Beyond X-rays

Although Röntgen is most famous for discovering X-rays, his broader body of work contributed to multiple areas of physics. He conducted research on the properties of crystals, the electrical behavior of dielectrics, and the thermal conductivity of gases. His experimental precision and focus on physical phenomena beyond immediate theoretical explanation reflected his pragmatic scientific philosophy.

Röntgen’s X-ray discovery, however, overshadowed his other scientific work, though his contributions to the study of elasticity and the piezoelectric effect remain recognized within physics [3].

6. Nobel Prize and Recognition

In 1901, Röntgen became the first laureate of the Nobel Prize in Physics, awarded “in recognition of the extraordinary services he has rendered by the discovery of the remarkable rays subsequently named after him” [4]. He refused to patent the discovery, insisting that the knowledge should benefit humanity freely, a decision that facilitated rapid global adoption of X-rays in medical and scientific contexts.

Röntgen received numerous honors during his lifetime, including honorary doctorates, medals, and membership in prestigious academies of science. Despite widespread fame, he remained modest, often preferring his laboratory to public life.

7. Impact on Medicine and Science

The discovery of X-rays transformed diagnostic medicine. For the first time, physicians could visualize the internal structure of the human body without invasive surgery. This capability revolutionized trauma care, orthopedics, and later oncology. Within months of Röntgen’s publication, hospitals worldwide were using X-rays for diagnostic purposes.

Beyond medicine, X-rays became essential tools in physics, chemistry, and materials science. They enabled studies of crystal structures, leading eventually to the development of X-ray crystallography, which would be pivotal in discoveries such as the structure of DNA.

The discovery also accelerated research in nuclear physics and radiation science, laying the foundation for radiotherapy, nuclear medicine, and advanced imaging technologies such as CT scans.

8. Later Life

Despite his fame, Röntgen lived modestly. He declined to use his discovery for personal financial gain, and after World War I, much of his fortune was lost due to inflation in Germany. He continued to work in physics until his retirement. His wife Anna Bertha died in 1919, and the couple had no biological children but adopted a niece, Josephine Bertha Ludwig.

Röntgen died on February 10, 1923, in Munich, Germany, from carcinoma of the intestine. His legacy endures in the medical and scientific communities worldwide, and his name remains immortalized in the “roentgen,” a unit once used to measure radiation exposure.

9. Legacy

Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen’s discovery marked the beginning of the modern era of medical imaging and radiological sciences. The societal and scientific impact of his work is vast, spanning healthcare, physics, engineering, and public health. His decision to release his discovery without seeking personal profit exemplifies a commitment to the advancement of science for the common good. Today, he is remembered not only as the discoverer of X-rays but also as a model of scientific integrity and humanitarian spirit.

References

- Glasser, O. Wilhelm Conrad Röntgen and the Early History of the Roentgen Rays. Charles C. Thomas, 1993.

- Assmus, A. "Early History of X Rays." Beam Line 27, no. 3 (1997): 10–17.

- Pais, A. Inward Bound: Of Matter and Forces in the Physical World. Oxford University Press, 1986.

- NobelPrize.org. “The Nobel Prize in Physics 1901.” https://www.nobelprize.org/prizes/physics/1901/rontgen/

Location: Lennep, Rhine Province, Kingdom of Prussia, German Confederation