| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Encyclopedia Editorial Office | -- | 1085 | 2025-08-06 09:58:47 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 1085 | 2025-08-07 05:17:59 | | |

Video Upload Options

Nutrition support refers to the administration of nutrients to individuals who are unable to maintain adequate nutrition through normal food intake. This support is crucial in both clinical and non-clinical settings and may be provided through oral, enteral, or parenteral routes, depending on the patient's condition. The goal is to provide essential macronutrients and micronutrients, promote recovery, and improve or maintain the quality of life. Nutrition support may be indicated for conditions such as severe malnutrition, dysphagia, or illnesses that affect the body’s ability to absorb or utilize nutrients.

1. Historical Background

The concept of nutrition support has evolved significantly over the centuries. In the early 20th century, nutrition therapy was primarily confined to treating basic deficiencies such as scurvy or rickets, caused by the lack of vitamins like Vitamin C or D. However, during World War II and beyond, advances in medical technology and research led to the development of more sophisticated forms of nutrition support. Notably, the introduction of intravenous (IV) feeding, or parenteral nutrition, in the mid-20th century revolutionized nutrition support for patients unable to take food orally.

The 1960s saw significant strides in the field of enteral nutrition, where liquid food was delivered directly into the stomach or intestines. The discovery of more refined methods of intravenous nutrition and the establishment of guidelines for enteral feeding led to better outcomes for critically ill patients. Over time, these techniques have become more tailored to meet individual nutritional needs and improve patient recovery rates [1].

Source: https://medlineplus.gov/nutritionalsupport.html

2. Types of Nutrition Support

2.1. Oral Nutrition Support

Oral nutrition support is often the first line of intervention for patients with insufficient oral intake but still able to swallow. It involves using specially formulated oral nutritional supplements (ONS), which are available in the form of drinks, powders, or gels. These products are designed to provide concentrated nutrients in smaller volumes, making them more accessible for those with a reduced appetite or difficulty consuming solid foods. Oral supplements are often used for patients with chronic diseases such as cancer, HIV/AIDS, and gastrointestinal disorders [2].

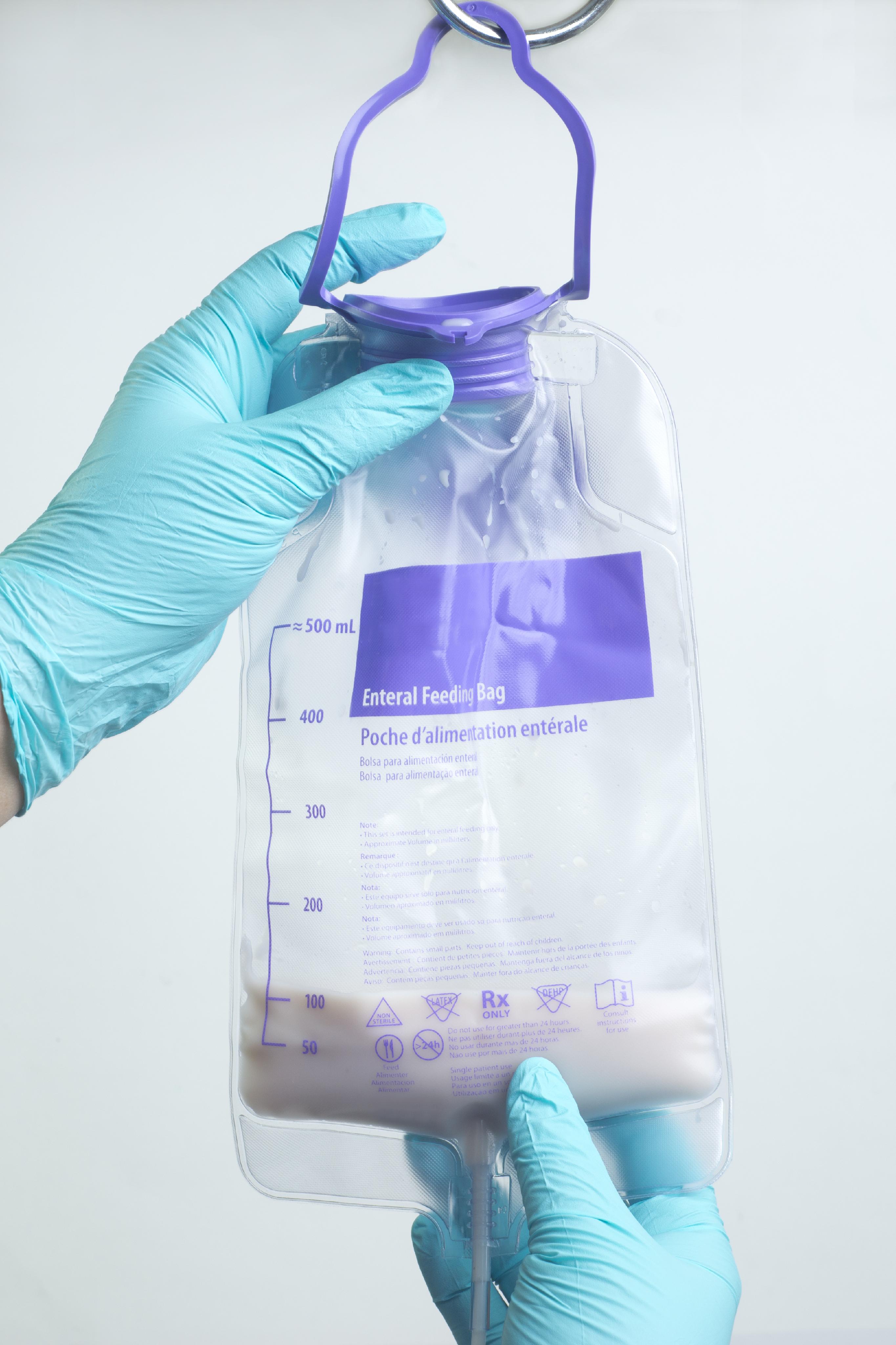

2.2. Enteral Nutrition Support

Enteral nutrition (EN) involves the delivery of nutrients directly into the gastrointestinal (GI) tract through a tube. It is indicated when a patient is unable to eat due to conditions affecting their ability to swallow or chew, such as stroke, surgery, or trauma. The most common types of enteral feeding methods include nasogastric tubes (NGT), percutaneous endoscopic gastrostomy (PEG) tubes, and jejunostomy tubes.

Enteral feeding ensures that the nutrients bypass the oral route while maintaining normal GI function, reducing the risk of complications associated with parenteral nutrition. It is often preferred for patients who have a functioning digestive system, as it preserves the gut’s immune function and reduces the risk of infection [3].

2.3. Parenteral Nutrition Support

Parenteral nutrition (PN) is used when a patient is unable to obtain sufficient nutrients via the GI tract, such as in cases of bowel obstruction, short bowel syndrome, or severe pancreatitis. Parenteral nutrition is administered intravenously, bypassing the GI tract entirely. It includes a mixture of carbohydrates, proteins, fats, vitamins, and minerals delivered directly into the bloodstream.

PN can be administered through peripheral veins (peripheral parenteral nutrition or PPN) or central veins (total parenteral nutrition or TPN). While TPN is more commonly used in long-term nutrition support, PPN is used for short-term cases where the nutritional needs are less demanding [4].

3. Indications for Nutrition Support

Nutrition support is recommended in various clinical settings where nutritional intake is compromised, including the following conditions:

-

Severe Malnutrition: Includes conditions like protein-energy malnutrition (PEM) or marasmus, where the body is significantly deprived of essential nutrients.

-

Trauma and Burns: Severe injury or burns result in increased energy expenditure and a higher nutritional demand.

-

Gastrointestinal Disorders: Includes conditions like Crohn’s disease, pancreatitis, and bowel obstructions where nutrient absorption is impaired.

-

Cancer and Chemotherapy: Patients undergoing cancer treatments often experience decreased appetite and malabsorption.

-

Neurological Disorders: Conditions such as stroke, dementia, or swallowing difficulties (dysphagia) may limit a patient's ability to consume sufficient food [1].

Nutrition support is also used in post-surgery recovery, in ICU settings for critically ill patients, and for individuals with advanced-stage diseases [2].

4. Clinical Applications and Benefits

Proper nutrition is essential for recovery, immunity, and overall health, and nutrition support plays a critical role in achieving these outcomes in clinical settings. Among the key benefits of nutrition support are:

-

Enhanced Healing: Adequate nutrition is essential for tissue repair, wound healing, and immune system support [5].

-

Improved Clinical Outcomes: Studies have shown that early and appropriate nutrition support can reduce the length of hospital stays, decrease complications, and improve recovery outcomes [6].

-

Prevention of Muscle Wasting: In critically ill patients, especially those on mechanical ventilation or in prolonged bed rest, nutrition support can help preserve muscle mass and prevent cachexia [7].

-

Reduced Mortality Rates: Patients receiving timely nutrition support, especially in ICU settings, have a lower risk of mortality, particularly those with malnutrition [6].

5. Challenges and Complications

While nutrition support offers significant benefits, there are several challenges and risks associated with its use:

-

Infections: Both enteral and parenteral feeding routes present risks of infection. Enteral feeding tubes can become infected or displaced, while parenteral nutrition poses a risk of bloodstream infections and sepsis.

-

Gastrointestinal Complications: Diarrhea, constipation, and bloating are common issues associated with enteral nutrition. Overfeeding or rapid administration can also lead to gastrointestinal distress [4].

-

Nutrient Imbalances: Ensuring the correct composition of nutrients is crucial, as incorrect formulations or dosages can lead to nutrient imbalances or deficiencies [7].

-

Cost and Accessibility: Parenteral nutrition, in particular, is costly and may not be accessible in all healthcare settings, especially in low-resource environments [2].

-

Psychological and Social Impact: For patients requiring long-term feeding support, there can be psychological impacts related to body image, social isolation, and the overall burden of treatment [5].

6. Future Directions in Nutrition Support

As medical technology continues to evolve, there are promising developments in the field of nutrition support:

-

Personalized Nutrition: Advances in genetic and metabolomics research may lead to more individualized nutrition support plans, tailored to the specific needs of each patient.

-

Home-Based Nutrition Support: Increased emphasis is being placed on delivering nutrition support at home, particularly for patients requiring long-term enteral or parenteral nutrition [3].

-

Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Nutrition Assessment: AI and machine learning tools may enhance the accuracy and efficiency of nutritional assessments and the development of support plans.

-

Telemedicine: Remote monitoring of nutrition support via telemedicine may allow for better oversight and quicker intervention, especially in the case of home patients [6].

References

- Evans, R. M., & Strychar, I. (2013). Oral Nutrition Support: Benefits and Risks. Nutrition in Clinical Practice, 28(6), 682–688.

- Jones, T. M., et al. (2018). Enteral Nutrition: Clinical Applications and Risk Management. Clinical Nutrition, 37(2), 352–360.

- Smith, K. W., & Collins, J. M. (2015). Total Parenteral Nutrition in Critical Care. Journal of Critical Care Medicine, 28(1), 101–110.

- Bistrian, B. R. (2017). Enteral and Parenteral Nutrition in Critical Illness. Nutritional Therapy in Critical Care, 28(3), 312–318.

- Jensen, G. L., & Compher, C. (2014). Adult Nutrition Support Guidelines. Journal of the American Dietetic Association, 114(2), 163–179.

- Hickson, M. (2018). The Importance of Nutrition Support in the Hospital Setting. British Journal of Nursing, 27(4), 234–240.

- Mattox, K. L. (2016). Nutrition Support for Critically Ill Patients: A Case-Based Approach. Critical Care Medicine, 44(2), 184–192.