| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | G.G. Flores-Rojas | -- | 876 | 2025-03-14 22:06:13 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | Meta information modification | 876 | 2025-03-17 01:43:00 | | |

Video Upload Options

Cellulose is a widely studied natural polymer due to its availability, biodegradability, non-toxicity, and ease of chemical modification. Currently, cellulose has many applications in science and technology, but it has vast relevance in biomedical applications, such as a protective coating for wound dressing in skin burns, and injuries to avoid bacterial infections. This chapter describes some properties of cellulose such as structure, and biocompatibility. Besides this chapter also describes some methods used to endow cellulose with antimicrobial activity by means of the addition of biocidal groups as N-halamines, quaternary ammonium salts, nanoparticles, enzymes, or through the incorporation of antibiotics for controlled drug delivery.

1. Properties of Cellulose

Cellulose is a straight-chain polysaccharide whose monomeric unit is the D-glucose dimer, consisting of two glucose molecules linked through a β-1-4-glycosidic bond, in which the C1 carbon of a glucose molecule and the C4 of the other are covalently bound to an oxygen atom [1]. The glucoside bond is stabilized by the hydrogen bonds between glucose hydroxyl groups and the oxygen in the bond, resulting in the linear configuration of the polymer. The aforementioned microscopic configuration of cellulose allows a more feasible interaction between chains, thus forming microfibrils bonded by Van der Waals forces and intermolecular hydrogen bonds, which promote the assembling of multiple cellulose chains stacking them in a stable and resistant three-dimensional structure. Microfibrils are made up of two structural regions: a crystalline structure, in which the cellulose chains are organized in a very orderly way, and an amorphous region, where the chains are disordered [2]. The crystalline regions can be extracted from the cellulose microfibrils by acid treatment, resulting in cellulose nanocrystals (CNC) or nanofibers (CNF) depending on the extraction material. The use of nanotechnology techniques allows the design and manufacture of natural cellulose NPs with different dimensions from 1 to 100 nm, from the fibers by homogenization, hydrolysis, or combined chemical and mechanical processes. Cellulose NPs give versatility and improve the properties of a given material [3].

Crystalline cellulose has four widely studied polymorphs (I, II, III, and IV). The first, cellulose type I, is the most abundant in nature since it is produced by plants, urochordates, algae, and bacteria. This structure can be modified to the other polymorphs [4], through a solubilization-recrystallization processes or by mercerization (aqueous sodium hydroxide treatments). Cellulose II has a monoclinic structure that gives it the greatest stability and has been used to produce various materials including cellophane, rayon, and synthetic textile fibers as the Tencel [5] . On the other hand, cellulose III is obtained from cellulose I or II by treatments with liquid ammonia. And finally, cellulose IV is produced by heat treatments of cellulose III [6].

Additionally, cellulose I is formed by two coexisting crystalline structures, whose proportion depends on the source of cellulose extraction; a triclinic structure (Iα) and a monoclinic structure (Iβ), which are named depending on their arrangement “parallel upwards” or “antiparallels” [1][7]. Although the polymorph Iα can be converted into Iβ through hydrothermal treatments (~260 C) in alkaline solution [8][9][10] or high-temperature treatments in organic solvents and inert atmosphere [11] complete conversion is not achieved.

For example, bacterial cellulose fibrils, when treated, can produce micro or nanofibrils [12], without altering their crystallinity, in general, the geometry of the BC is determined by intramolecular and intermolecular forces such as bonds of hydrogen and hydrophobic and Van der Waals interactions, and forms parallel chains (cellulose I). When carrying out the mercerization process (treatment with 5–30 wt% of sodium hydroxide), this material forms a type II antiparallel structure, mostly stabilized by hydrogen bonds, which generates a more stable threedimensional arrangement than cellulose I and nanofibers with random structure and high Young modulus, 118 GPa for a single BC filament almost comparable to Kevlar® and steel [13]. Cellulose micro and nanofibrils have a high surface area, which is related to high porosity and allows greater interaction between the fibrils and decreases the permeability of the material to oxygen. Furthermore, due to a large number of free hydroxyl groups, they show great adsorption of water and the formation of high-viscosity gels. Another advantage of hydroxyl groups is that they can be functionalized by esterification, oxidation, or sulfonation, altering the properties of the biopolymer and expanding the application [14].

2. Chemical Modification of Cellulose

Cellulose has a large number of hydroxyl groups, which are reactive and act as active sites, allowing a wide variety of chemical modifications that result in unique cellulose derivatives [15]

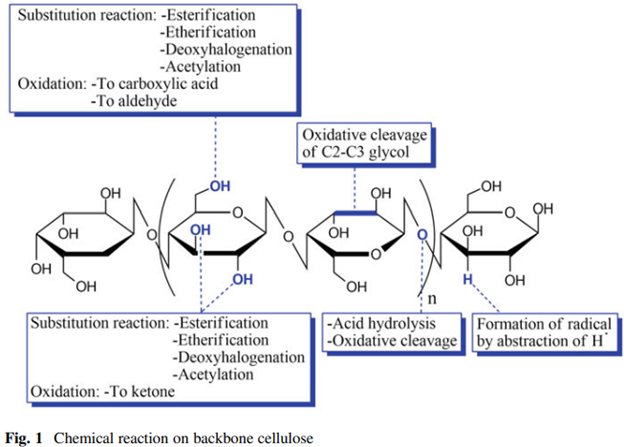

Chemical modifications provide cellulosic materials with antimicrobial activity by incorporating biocidal agents either by covalent bonds or cellulose binding interactions. The main chemical methods of cellulose modification include esterifications, etherifications, and hydroxyl group oxidation reactions. Other chemical modifications include ionic and radical grafting, acetylation, and deoxyhalogenation (Fig. 1). These chemical modifications may provoke drastic changes in the cellulose solubility allowing water and organic solvents to dissolve it.

Chemical modification of cellulose with different functional groups allows the design of antiadhesive and biocidal materials. Functional groups include siloxanes, silanes, amines, hydrazide, acyl hydrazide, aminooxy, alkenes, alkoxysilanes, acyl chlorides, epoxides, and isocyanates. Although cellulose may require a pretreatment to insert more complex functional groups, the chemical modification is a great alternative for the fabrication of diverse materials at different scales, which is achieved by two approaches: from intermediates or semi-finished materials, Fig. 2 shows an overview of the chemical modification process of cellulose.

References

- Azizi Samir MAS, Alloin F, Dufresne A. Review of recent research into cellulosic whiskers, their properties and their application in nanocomposite field.. Biomacromolecules . 2005, 6(2), 612–626.

- Nishiyama Y. Structure and properties of the cellulose microfibril.. J Wood Sci . 2009, 55 (4), 241–249.

- Vasconcelos NF, Feitosa JPA, da Gama FMP, Morais JPS, Andrade FK, de Souza Filho M, de Rosa MF. Bacterial cellulose nanocrystals produced under different hydrolysis conditions: properties and morphological features.. Carbohydr Polym . 2017, 155, 425–431.

- O’Sullvian ACC. Cellulose: the structure slowly unravels. Cellulose . 1997, 4(3), 173–207.

- Klemm D, Heublein B, Fink HP, Bohn A. Cellulose: fascinating biopolymer and sustainable raw material.. Angew Chem Int Ed. 2005, 44(22), 3358–3393.

- Ishikawa A, Okano T, Sugiyama J. Fine structure and tensile properties of ramie fibres in the crystalline form of cellulose I, II, IIII and IVI. . Polymer. 1997, 38(2), 463–468.

- Nishiyama Y. Structure and properties of the cellulose microfibril.. J Wood Sci . 2009, 55 (4), 241–249..

- Yamamoto H, Horii F. CPMAS carbon-13 NMR analysis of the crystal transformation induced for Valonia cellulose by annealing at high temperatures.. Macromolecules . 1993, 26 (6), 1313–1317.

- Watanabe A, Morita S, Ozaki Y. Study on temperature-dependent changes in hydrogen bonds in cellulose Iβ by infrared spectroscopy with perturbation-correlation moving-window two-dimensional correlation spectroscopy. Biomacromolecules . 2006, 7(11), 3164–3170.

- Horikawa Y, Sugiyama J. Localization of crystalline allomorphs in cellulose microfibril. Biomacromolecules . 2009, 10(8), 2235–2239.

- Debzi EM, Chanzy H, Sugiyama J, Tekely P, Excoffier G. The Iα !Iβ transformation of highly crystalline cellulose by annealing in various mediums. . Macromolecules . 1991, 24 (26), 6816–6822.

- Costa AFS, Almeida FCG, Vinhas GM, Sarubbo LA. Production of bacterial cellulose by Gluconacetobacter hansenii using corn steep liquor as nutrient sources. Front Microbiol . 2017, 8, 1–12.

- Picheth GF, Pirich CL, Sierakowski MR, Woehl MA, Sakakibara CN, de Souza CF, Martin AA, da Silva R, de Freitas RA. Bacterial cellulose in biomedical applications: a review. Int J Biol Macromol . 2017, 104, 97–106.

- Berto GL, Arantes V. Kinetic changes in cellulose properties during defibrillation into microfibrillated cellulose and cellulose nanofibrils by ultra-refining. Int J Biol Macromol . 2019, 127, 637–648.

- Jedvert K, Heinze T. Cellulose modification and shaping - a review. . . J Polym Eng . 2017, 37 (9), 845–860.