| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Encyclopedia Editorial Office | -- | 874 | 2025-03-11 09:37:20 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | Meta information modification | 874 | 2025-03-19 02:07:39 | | |

Video Upload Options

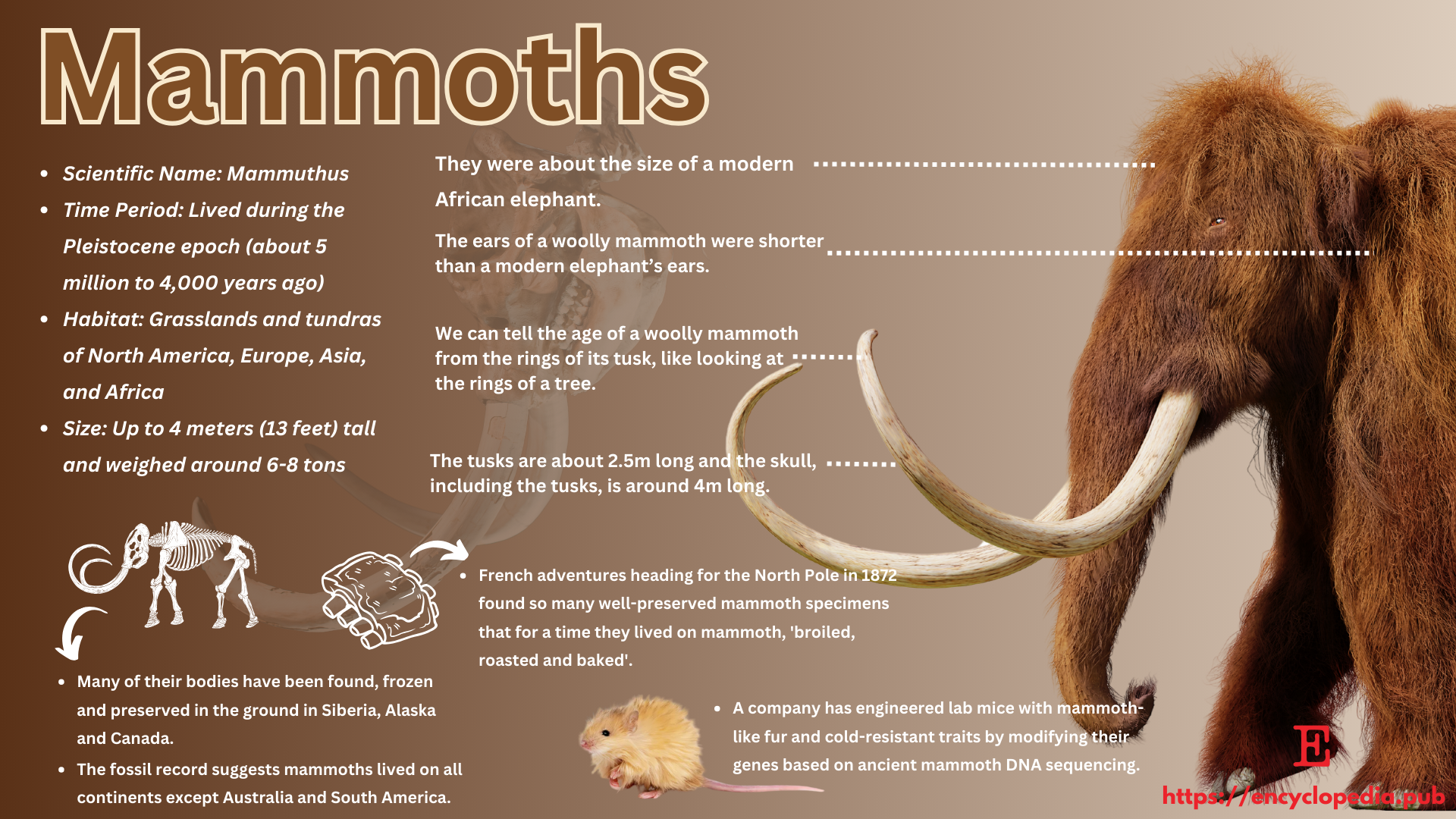

The woolly mammoth (Mammuthus primigenius) was a large, elephant-like mammal that lived during the Ice Age. It belonged to the family Elephantidae, which includes modern elephants. It was characterized by its long, curved tusks, thick fur, and adaptations to extremely cold climates. The woolly mammoth was one of the last surviving members of the Mammuthus genus and played a significant role in Pleistocene ecosystems. Its extinction around 4,000 years ago was due to a combination of climate change and human activity.

1. Introduction

The woolly mammoth was one of the most iconic prehistoric animals, often associated with Ice Age landscapes and early human societies. It roamed the vast tundra and steppe regions of Eurasia and North America, coexisting with species like the saber-toothed cat, cave bear, and giant ground sloth. Early humans hunted woolly mammoths for meat, hides, and bones, which they used for tools and shelter. Mammoth imagery appears in ancient cave paintings, highlighting its cultural and ecological significance.

By Lou.gruber - Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=3524067

2. Physical Characteristics

Woolly mammoths were well adapted to the harsh, icy environments of the Pleistocene. Their thick coat of fur, which could reach up to 90 cm (3 feet) in length, helped insulate them against the cold. The fur was composed of a dense undercoat and a longer, coarse outer layer. Beneath the skin, they had a layer of fat up to 10 cm (4 inches) thick, providing additional warmth.

Adult woolly mammoths stood between 2.7 and 3.4 meters (9 to 11 feet) tall at the shoulder and weighed between 4,500 and 6,800 kg (10,000 to 15,000 lbs), similar in size to modern African elephants (Loxodonta africana). Their long, curved tusks could grow up to 4.2 meters (14 feet) long and were used for digging through snow, defense, and displays of dominance among males.

Genetic studies indicate that woolly mammoths also had small ears and short tails to reduce heat loss, a trait seen in modern arctic animals. Their hemoglobin was adapted to efficiently transport oxygen in cold temperatures.

By Thomas Quine - https://www.flickr.com/photos/quinet/44598416660/, CC BY 2.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=80400437

3. Habitat and Distribution

Woolly mammoths were widespread across the northern hemisphere, from Europe and Siberia to North America. Their primary habitat was the mammoth steppe, an expansive, treeless grassland that covered parts of Russia, Canada, Alaska, and Scandinavia during the Ice Age. This environment was rich in grasses, shrubs, and mosses, which provided an abundant food source.

The cold, dry conditions of the Pleistocene were ideal for woolly mammoths. However, as the climate warmed after the Ice Age, forests expanded, reducing the open grasslands that the mammoths depended on.

4. Diet and Behavior

Woolly mammoths were herbivores, consuming grasses, sedges, shrubs, mosses, and even small trees. Their large, flat molars were specialized for grinding tough plant material. A single adult mammoth needed to consume around 150 kg (330 lbs) of food per day to sustain its massive body.

Fossil evidence and modern elephant behavior suggest that woolly mammoths lived in matriarchal herds, led by an older female. These herds provided protection, social bonding, and guidance in finding food. Males likely left the herd upon reaching maturity, leading solitary lives or forming small bachelor groups.

Evidence from preserved mammoth dung and stomach contents found in permafrost indicates that their diet varied with the seasons, much like modern elephants.

5. Extinction

The woolly mammoth disappeared around 10,000 years ago from most of its range due to a combination of factors:

- Climate Change: As the Ice Age ended, rising temperatures led to the expansion of forests and the reduction of open grasslands, limiting their food sources.

- Human Hunting: Early human societies hunted mammoths for food, skins, and bones. Archaeological sites show evidence of mammoth butchering, suggesting that humans played a role in their decline.

- Genetic Decline: Studies on the last mammoth populations from Wrangel Island suggest that inbreeding and genetic mutations weakened them before their final extinction [1].

The last known population survived on Wrangel Island, in the Arctic Ocean, until about 1650 BCE, long after most other woolly mammoths had vanished.

6. Fossil Discoveries and Research

Woolly mammoth fossils have been found across Europe, North America, and Asia, with some exceptionally well-preserved specimens recovered from Siberian permafrost. These frozen mammoths provide unique insights into their physiology and even contain intact DNA, stomach contents, and muscle tissue.

One of the most famous discoveries was the Yuka mammoth, a 39,000-year-old carcass found in Siberia in 2010, which had preserved skin, muscle, and hair. Such discoveries help scientists understand mammoth genetics and Ice Age ecology [2].

7. Modern Efforts and De-Extinction

Scientists are exploring de-extinction efforts to bring back woolly mammoths using genetic engineering. By editing the genome of Asian elephants—their closest living relatives—researchers hope to create a hybrid species with mammoth-like traits, capable of thriving in Arctic environments [3].

However, there are ethical and ecological concerns, including the feasibility of reintroducing a resurrected species into modern ecosystems. Some argue that efforts should focus on conserving existing endangered species instead.

8. Conclusion

The woolly mammoth remains one of the most fascinating prehistoric creatures, playing a key role in Ice Age ecosystems and human history. From fossil discoveries to de-extinction projects, its legacy continues to inspire scientific research and public interest.

References

- Palkopoulou, E., et al. (2015). "Complete genomes reveal signatures of demographic and genetic declines in the woolly mammoth." Current Biology, 25(10), 1395-1400.

- Lister, A., & Bahn, P. (2007). Mammoths: Giants of the Ice Age. Frances Lincoln.

- Shapiro, B. (2015). How to Clone a Mammoth: The Science of De-Extinction. Princeton University Press.