| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Francisco Bergson Moura | -- | 3615 | 2024-12-12 14:35:24 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | -993 word(s) | 2622 | 2024-12-13 00:46:29 | | | | |

| 3 | Catherine Yang | Meta information modification | 2622 | 2024-12-13 00:48:22 | | |

Video Upload Options

This work aims to investigate the dynamics of the rabies virus in the Desmodus rotundus species.

1. Introduction

Chiroptera, a notable group of mammals, possess a unique ability to carry pathogens without falling ill for extended periods. Their capability to fly long distances renders them potential vectors and reservoirs for various diseases. However, little is known about the diseases to which they succumb or reasons for their apparent resistance to numerous pathogens [1].

The order Chiroptera consists of consists of 1,120 species, includes the vampire bats from the family Phyllostomidae and the subfamily Desmodontinae. These bats consist of three Neotropical species only found in the New World [2][3][4][5].

The common vampire bat, D. Rotundus. is the primary reservoir for rabies in both humans and livestock [6]. This species has thrived due to habitat alterations resulting from increased livestock activity [7], which is regarded as one of the key productive activities that have inevitably exposed herbivores to this species and the rabies virus [8].

Although not the most represented mammalian order among zoonotic hosts, bats host more zoonotic viruses per species than rodents. Most resulting zoonoses have been high-profile spillover incidents of extreme pathogenicity [9].

Bats, distinct from other mammals, are often recognized for their gregarious social organization and ability to fly. This evolution has beneficial consequences for their lifespan and immunological functioning without the manifestation of noticeable disease [9]. Moreover, they act as significant hosts, transmitting approximately 200 different types of viruses, including the rabies virus and potentially harmful bacteria [10][11]. The role of bats as reservoirs for emerging infectious diseases has increasingly gained recognition [12].

2. Material and Methods

This study is quantitative and descriptive based on laboratory diagnoses.

The animals were sampled in three municipalities of great epidemiological importance for rabies in the public health and livestock fields: Potiretama (-5ᵒ 43’ 26” S, 38ᵒ 09’ 22” W), Tauá (6ᵒ 00’ 11” S, 40ᵒ 17’ 34” W), and Granja (3ᵒ 07' 13” S, 40ᵒ 49’ 34” W). These are located to the east, southwest, and northwest of the State of Ceará, respectively. Both municipalities experience a Hot Semi-arid Tropical climate with temperature variations between 26ᵒC and 28ᵒC. They also feature similar vegetation types, with open shrubby Caatinga vegetation in Potiretama and Tauá, and Cerrado vegetation in Granja. However, they differ in annual rainfall rates: 790.4, 597.2, and 1,039.9 mm, respectively [13] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Municipalities with great epidemiological importance of rabies in the area of public health and livestock. Source: QGIS 2.18.15

A total of 134 bats from the hematophagous species D. rotundus were captured adhering to inclusion criteria of young and adult age categories in males and females [14]. Their reproductive status was determined through visual verification, and divided into categories: scrotal males (young and adult males with visible testicles in the scrotal sac) and innate females (young and adult females with normal abdomen and undeveloped breasts). No material was extracted from pregnant females (adult females with a detectable fetus upon abdomen palpation) and lactating females (adult females with fully developed breasts) [15][16], to prevent compromising the species’ population.

Field procedures commenced only after analysis and authorization from the Ethics Committee for the Use of Animals (CEUA) No. 5495335/2017 and the Biodiversity Authorization and Information System (SISBIO) No. 82878/2021. Capture sessions started minutes before dusk, using mist nets measuring 7 x 2.5 m, opened to ground level, and lasted a few hours until dawn. There was no discernible pattern in the number of mist nets used or the working hours. After capture, the bats were housed in metal cages measuring 40x 30 x 25 centimeters, with a maximum of 20 animals per cage until the following morning, when sample collection began. This research did not receive any specific grants from public, commercial, or not-for-profit funding agencies.

The captured bats were anesthetized and euthanized using a fast-acting inhalation anesthetic, isoflurane 2-chloro-2-(dif)-1, 1, 1-trifluoro-ethane, at a concentration > 1 MAC (Minimum Alveolar Concentration). This method is suggested for small mammals according to Resolution No. 714, dated June 20, 2002, as proposed by the Federal Council of Veterinary Medicine. The animals were placed in a purpose-built chamber, ensuring uniform distribution of the anesthetic. This quick-acting concentration facilitated anesthesia and euthanasia via dose-dependent cardiac and respiratory depression, also leading to increased hypotension, thereby sparing them any suffering.

The collection of neural material (brain) was performed by aspiration, using a 170 mm polypropylene Pasteur pipette with a 3 mm diameter tip, possessing a 3 ml capacity, through the foramen magnum [17]. The head was dissected at the level of the atlanto-occipital joint, and the foramen magnum was then cleared with the help of small anatomical forceps to remove the atlas vertebra. The pipette’s tip was inserted through the foramen magnum to aspirate the brain material. This material was immediately deposited in Eppendorf tubes and refrigerated for later laboratory tests: Direct Immunofluorescence and Mouse Inoculation.

Mouse inoculation tests were conducted at the Central Public Health Laboratory of Ceará (LACEN) and the Laboratory of Viral Zoonoses (LVZ), which is a part of the Department of Preventive Medicine of the Faculty of Veterinary Medicine at the University of São Paulo (USP). The aim was to determine whether the captured animals were infected with the rabies virus and the presence of protein nature antigens in their tissues. The Laboratory of Viral Zoonoses (USP) also carried out the molecular diagnosis of the rabies virus using the reverse transcriptase reaction followed by the polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR) with specific primers for the gene encoding the virus nucleoprotein.

When carrying out the Direct Immunofluorescence (DIF) test, impressions of central nervous system fragments were placed on glass slides and fixed in acetone for at least 30 min at -20°C. After the fixation and drying process, the samples were ringed with nail polish on slides that were previously marked with two circles, to keep the conjugate in place. These were then incubated in a humid chamber for 30 min at 37°C. The slides were rinsed with buffered saline solution (pH between 7.2 and 7.5) and distilled water to prevent the formation of crystals. After additional drying, a drop of immersion oil was instilled for examination [18].

The procedure for inoculating mice first involves creating 20% suspensions, and then proceeding with the inoculations the updated mice. One gram from varying central nervous system fragments is weighed to prepare the suspensions, then macerated and integrated with 4 ml of virus diluents. This is followed by a centrifugation process for 15 min after which the supernatants are removed. The preparations are stored at a temperature between 2 to 8°C for inoculation into the mice on the same day, primarily via the intracerebral route (IC). The IC inoculations are administered to mice either 5 days old (0.01 ml per animal) or mice 21 days old weighing between 11 to 14 grams (0.03 ml per animal). Documentation-wise, identification and reading sheets for the samples are created, with 8 to 10 mice being used per each inoculation session. Daily readings continue for 30 days considering the samples hail from hematophagous bats (wild animals). Notes detailing the list of deceased, untreated and euthanized animals are maintained as well. Animals expiring beyond the fifth day of inoculation undergo the IFD test. Disposable 1ml syringes are primarily employed for inoculations – these permit dosages of 0.03ml and take needles of a maximum caliber of 13 x 4.5 The animal subjects are euthanized via cervical dislocation once tests are completed, adhering to Normative Resolution No. 37 issued on 02/15/2018 by the National Council for Control of Animal Experimentation (CONCEA) to maintain good laboratory practices [18].

In the single-sample Nucleoprotein and Cytochrome Oxidase 1 Amplification Assay, nucleic acid extracted using the QIAquick ™ kit (Qiagen - Valencia, CA, USA), adhering to the manufacturer’s instructions. Positive and negative controls were established using rabies virus (RABV) samples derived from mouse brains and nuclease-free water, respectively [19]. For the synthesis of the complementary DNA strand, reverse transcriptase was employed, which was then followed by partial amplification of the gene encoding the N protein [20]. Three primers were utilized for amplifying the N gene: 21G, 504 and 304 [21], plus a pair of primers for amplifying Cytochrome Oxidase 1 (LCO-HCO) [22]. The PCR product was purified using the QIAquick ™ Gel Extraction Kit (Qiagen - Valencia, CA, USA), and gel-purified bands were acquired with a 1% Agarose gel and the QIAquick® gel extraction kit, as per the manufacturer’s guidance. After purification, DNA was quantified visually on a 2% Agarose gel with a low-mass DNA ladder (Invitrogen - Carlsbad, CA, USA), in compliance with the manufacturer’s instructions.

3. Results

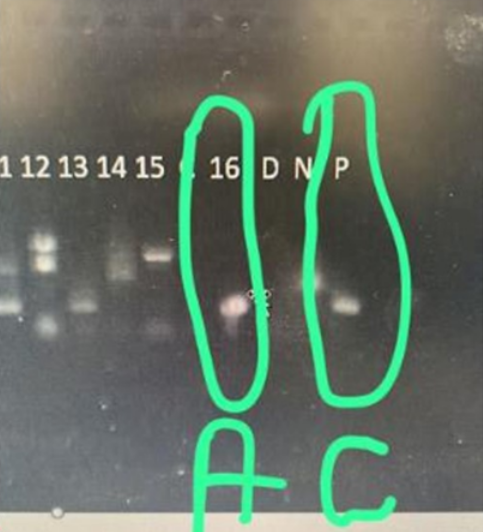

The research results obtained for the circulation of the rabies virus were negative in 133 (99.25%) of the specimens (Table 1), aligning with the health conditions of the specimens analyzed in the two aforementioned reference laboratories. Only 1 (0.75%) specimen tested positive for both Direct Immunofluorescence and Mouse Inoculation diagnoses, which was then submitted for further confirmation via RT-PCR diagnosis (Figure 2).

Table 1. Laboratory results of Direct Immunofluorescence and Inoculation in Mice of hematophagous bats Desmodus rotundus from the municipalities of Potiretama, Tauá and Granja, Ceará.

|

Municipality |

No. of samples |

Animal |

Organ |

Results (IFD, IC) |

|

Potiretama |

85 |

Desmodus rotundus |

Brain |

All negative |

|

Granja |

30 |

Desmodus rotundus |

Brain |

29 Negatives 01 Positive |

|

Tauá |

19 |

Desmodus rotundus |

Brain |

All negative |

|

TOTAL |

134 |

Desmodus rotundus |

Brain |

133 Negatives 01 Positive |

Caption: IFD – Direct Immunofluorescence. IC – Mouse Inoculation Source: LACEN/CE and LVZ/USP

Figure 2. Positive result of the RT-PCR molecular diagnosis of the only hematophagous bat Desmodus rotundus. Legend: A – sample number, C – positive control. Source: LVZ/USP.

4. Discussion

The diversity of viruses associated with bats has led many studies to focus on understanding how these animals can carry numerous pathogens without necessarily succumbing to the diseases these microorganisms cause. It is hypothesized that the ability to fly could be the key to explaining these animal’s resistance to viruses and other pathogens. During flight, metabolism increases, consequently raising the levels of free oxygen radicals. This, in turn, generates more molecules that damage DNA. To prevent unwanted inflammatory responses to damaged DNA, bats have evolved mechanisms to suppress inflammation [23].

The observation of the low prevalence of the rabies virus in the species D. rotundus has been consistent over the years. Sugay and Nilsson [24] discovered a relatively low ratio of rabies virus isolations in D. rotundus bats. Indeed, merely 11 (2.21%) out of 496 specimens studied were from areas where rabies was present in the State of São Paulo.

A study [25] discovered that the rabies virus in naturally infected Chiroptera occurs more often in insectivorous bats compared to other bat species, including D. rotundus.

During 2008 and 2009, rabies outbreaks took place in the municipality of Potiretama. This required intervention from the Rabies Surveillance and Control Program of the Health Department of the State of Ceará. Their key objectives were preventing cases of human rabies originating from the wild cycle and monitoring risk factors for the occurrence of rural rabies. As an outcome of their routine work, they discovered only one D. rotundus bat roost. They investigated 18 locations, three of which had deceased animals (cattle, horses, sheep, goats, and lambs) presenting symptoms of rabies. They captured 52 D. rotundus bats for rabies diagnosis, with all results returning negative.

A study on the isolation of the rabies virus [26], involving 6,389 bats. Out of those, 311 (5.6%) were of the hematophagous species D. rotundus, with none of the specimens diagnosed with the rabies virus in the study area during the specified period. The families with the highest number of instances were the insectivorous Vespertilionidae (37/0.57%) and Molossidae (21/0.32%), followed by the Phyllostomidae (18/0.28%).

In their studies, [27][28] it was cited that epidemiological investigations of rabies in wild animals demonstrated how the rabies virus can specifically adapt and transmit to a certain species, becoming less capable of infecting other species. This host-parasite relationship is referred to as the compartmentalization of the rabies virus. Some authors suggest that this compartmentalization exists when the rabies virus in a certain bat species does not exhibit characteristics similar to viruses isolated from other bat species.

According to [23], bats are well equipped to control viral infections through mechanisms that limit inflammation and, consequently, the incidental damage these responses might cause in their bodies. Not only have mutations been observed but also suppression of expression and low activity of molecules involved in inflammatory responses in bats. This allows their immune system to manage viruses without triggering an overblown inflammatory response, which could result in tissue damage and deteriorating health conditions. This may be critical mechanism that explains the longevity and status of bats as virus reservoirs.

The mechanisms of inflammatory limitations in bats are primarily related to viral pattern recognition receptors and the initiation of signaling events. These results in the production of cytokines involved in viral evasion of the host’s IFN response [23][29].

The molecular patterns utilized by the host to detect viral infections are more restricted than those used to discern bacterial invasions; these generally consist of nucleic acid recognition. Viral DNA and RNA are identified by several distinct classes of host pattern recognition receptors [30].

The Retinoic Acid-inducible Gene-I Like receptor (RIG-I) serves as a vital component in the innate immune system for recognizing virus-infected cells and orchestrating the Interferon type 1 (IFN-1) response. Similar to RIG-I, Cytoplasmic RLRs detect viral dsRNA within the Cytosol [29][30][31][32].

Endosomal Toll-like receptors (TLRs) 3, 7, 8, and 9 have, for the most part, evolved under similar functional constraints as in other mammals. Among these, D. rotundus exhibits classical genetic characteristics. TLRs 3, 7, and 8 recognize viral RNA, while TLR 9 recognizes viral, bacterial, and protozoan DNA [30].

Intracellular nucleotide oligomerization domain (NOD) receptors recognize pathogens due to entry by or through membrane pores, and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs), which are associated with cellular stress.

Nucleotidyltransferase (cGAS) is a cytosolic DNA sensor that activates a type I interferon response [30][31][32].

According to [33], micro-RNAs are a family of small, endogenous RNAs that do not code for proteins. They are approximately 21-24 nucleotides long and regulate gene expression through translational repression or degradation of their complementary mRNAs. Originating from tiny endogenous precursor structures of the stem-loop type they regulate various eukaryotic processes, including virus-host cell interaction, immunity, and cell death. Beyond these functions, micro-RNAs are significant negative regulators of eukaryotic gene expression. MicroRNA clusters that evolve rapidly seem to target genes managing virus-host interactions in bats, dampening inflammatory responses. This process limits both immunopathology and possibly energy expenditure. These genes include those that are active in antiviral immunity, DNA damage response, apoptosis and autophagy. One example of this is found in the flying fox bat of the Pteropus alecto species, which serves as a natural reservoir for the human pathogens Hendra virus and Australian Bat lyssavirus [30].

The recent discovery of viral endogenous elements in animal genomes suggests that bat immune systems may be able to accept pathogens as intrinsic parts of their organism. However, this pathogen tolerance in bats is not universal, as severe morbidity and mortality in bats can result from infection by certain viral, bacterial, and fungal pathogens. In the majority of these cases, it is the host’s immunopathological response rather than the pathogen itself, that is primarily responsible for mortality. A possible major exception to this is rabies-related mortality, where the virus can cause direct pathology in the central nervous system while completely evading immune detection [9].

In addition to the molecular patterns leveraged by the host to identify viral infections, there’s evidence suggesting that bats have evolved adaptive intracellular mitochondria to alleviate the oxidative stress accumulated during metabolically intensive activities such as flying. Current research emphasizes an increasing recognition of mitochondria’s crucial role in cellular signaling and defense. It is proposed that bats could control pathogenesis in microbe-invaded cells via autophagy and apoptosis processes, which initially evolved to manage metabolic stress, thereby evading immunopathological consequences. However, these control mechanisms are restricted to intracellular pathways, rendering bats susceptible to the immunopathological ramifications of attempted extracellular infections [9].

5. Conclusion

Although significant circulation of the rabies virus has not been observed among hematophagous bats, specifically D. rotundus, it appears that this species can restrict immune responses to avoid immunopathology in a rabies virus infection, underscoring a deep evolutionary history. As such, this research serves as an important tool in understanding the immunological dynamics, maintenance, and circulation of the rabies virus within the D. rotundus species.

References

- Buckles EL. Chiroptera (Bats). In: Fowler’s Zoo and Wild Animal Medicine, Volume 8. Elsevier; 2015. p. 281–90.

- Santos AP dos, Mottin VD, Aita RS, Franciscatto C, Lopes ST dos A, Franco W dos S, et al. Hematological and biochemical values of vampire bats (Desmodus rotundus) in southern Brazil. Acta Sci Vet. 2018; 35 (1):55. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.22456/1679-9216.15813.

- Almeida BFM, Barbosa TS, Ciarlini LSRP. Hematological values of vampire bats Desmodus rotundus (E. Geoffroy, 1810) suspended in captivity. 16: 780–5.

- Seetahal JFR, Sanchez- Vazquez MJ, Vokaty A, Carrington CVF, Mahabir R, Adesiyun AA, et al. Of bats and cattle: The epidemiology of rabies in Trinidad, West Indies. Vet Microbiol 2019; 228:93 –100. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.vetmic.2018.11.020.

- Rocha F, Dias RA. The common vampire bat Desmodus rotundus (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae) and rabies virus transmission to livestock: a contact network approach and recommendations for surveillance and control, Preventive Veterinary Medicine, 2019. Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 2019.

- Becker DJ, Broos A, Bergner LM, Meza DK, Simmons NB, Fenton MB, et al. Temporal patterns of vampire bat rabies and host connectivity in Beliz. bioRxiv, 2020. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1101/2020.07.16.204446.

- Sanchez-Gomez WS, Selem-Salas CI, Cordova-Aldana DI, Erales-Villamil JA. Common vampire bat (Desmodus rotundus) abundance and frequency of attacks to cattle in landscapes of Yucatan , Mexico. Trop Anim Health Prod. 2022; 54 (2):130. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11250-022-03122-w.

- Mendoza-Sáenz VH, Navarrete -Gutiérrez DA, Jiménez-Ferrer G, Kraker-Castañeda C, Saldaña-Vázquez RA. The abundance of the common vampire bat and feeding prevalence on cattle along a gradient of landscape disturbance in southeastern Mexico. Mamm Res. 2021; 66 (3):481–95. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s13364-021-00572-9.

- Brook CE, Dobson AP. Bats as special reservoirs for emerging zoonotic pathogens . Trends in microbiology. 2015; (23):172–80.

- Horta D, Oliveira DG, Miranda EM. Serological survey of rabies virus infection among bats in Brazil. Virus Rev Res 2018; (23):1–10.

- Menezes PQ. Hematological reference intervals of the bat Tardarida brasiliensis (Molossidae, Chiroptera) in Southern Brazil. 2020. 84f. Dissertation (Master’s Degree in). Animal Biology) Institute of Biology.

- Kuzmin IV, Bozick B, Guagliardo SA. Bats, emerging infectious diseases, and the rabies paradigm revisited. Emerging Health Threats Journal. 2011.

- Ceará Institute of Economic Research and Strategy. 2017.

- Anthony ELP. Age determination in bats. In: Kunz TH, ed. Ecological and behavioral methods for the study of bats. Washington: Smithsonian Institution; 1988. p. 47–58.

- Sekiama ML. A study on bats addressing occurrence and captures, reproductive aspects, diet, and seed dispersal in Iguaçu National Park. In: Chiroptera; Mammalia) 2003 80 f: il Thesis (Doctorate. Paraná, Brazil (Curitiba).

- Zortéa M. Reproductive patterns and feeding habits of three nectarivorous bats (Phyllostomidae: Glossophaginae) from the Brazilian Cerrado. Brazilian Journal of Biology. 2003; 63 (1):159–68.

- King AA, Palmer SR, Soulsby L. Zoonosis. Simpson DIH, organizer. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 1998.

- Health Surveillance Secretariat. Department of Epidemiological Surveillance. Rabies Laboratory Diagnosis Manual / Ministry of Health, Health Surveillance Secretariat, Department of Epidemiological Surveillance. In: Ministry of Health Publishing House. Brasilia; 2008.

- Fahl WO, Carnieli P Jr, Castilho JG, Carrieri ML, Kotait I, Iamamoto K, et al. Desmodus rotundus and Artibeus spp. bats might present distinct rabies virus lineages. Braz J Infect Dis. 2012; 16 (6):545–51. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.bjid.2012.07.002.

- Carnieli P Jr, Fahl W de O, Castilho JG, Oliveira R de N, Macedo CI, Durymanova E, et al. Characterization of Rabies virus isolated from canids and identification of the main wild canid host in Northeastern Brazil, Virus Res. 2008; 131 (1):33–46. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.virusres.2007.08.007.

- Orciari LA, Niezgoda M, Hanlon CA, Shaddock JH, Sanderlin DW, Yager PA, et al. Rapid elimination of SAG-2 rabies virus from dogs after oral vaccination. Vaccine. 2001;19(31):4511–8. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/s0264-410 x (01)00186-4.

- Folmer OF, Lutz RA. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial cytochrome c oxidase subunit I from various metazoan invertebrates. Marine Molecular Biology and Biotechnology. 1994; 3(5):294–9.

- Moratelli R, Neto APC, Filardy A. Bats and deadly viruses. “Julio de Mesquita Filho” State University of São Paulo.

- Sugay W, Nilsson MR. Isolation of rabies virus from vampire bats from São Paulo State, Brazil. Bulletin of La Oficina Santaria Panamericana. 1966; 310–5.

- Scheffer KC, Carrieri ML, Albas A. Rabies virus in naturally infected bats in the State of São Paulo, Brazil infected bats in the State of Sao Paulo. Southeastern Brazil Public Health Review. 2007; 389–95.

- Favaro ABBC. Positivity for rabies virus in bats in the state of São Paulo and potential risk factors. Aracatuba; 2018.

- Scheffer KC. Detection of rabies virus in organs of bats of the genus Artibeus (Leach, 1821) RT-PCR, Hemi-Nested RT-PCR and Real-Time RT-PCR. 2011. 145 f.: ill. Thesis (Doctorate in Experimental Epidemiology Applied to Zoonoses) - Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Science. São Paulo.

- Fahl WO. Molecular markers for the pathogenesis of rabies virus: the relationship among incubation periods, viral load and the genes encoding the viral P and L proteins. Thesis (Doctorate in Science) - Faculty of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Science, University of São Paulo, São Paulo.

- Matsumiya T, Stafforini DM. Function and regulation of retinoic acid-inducible gene-I. Crit Rev Immunol. 2010; 30(6):489–513. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1615/critrevimmunol.v30.i6.10.

- Beltz LA. Bats and human health: Ebola, SARS, rabies and beyond. John Wiley & Sons; 2017.

- Solis M, Nakhaei P, Jalalirad M, Lacoste J, Douville R, Arguello M, et al. RIG-I-mediated antiviral signaling is inhibited in HIV-1 infection by protease-mediated RIG-I sequestration. J Virol. 2011; 85 (3):1224–36. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1128/jvi.01635-10.

- Kell AM, Gale M Jr. RIG-I in RNA viruses recognition. Virology. 2015; 479–480:110–21. Available at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.virol.2015.02.017.

- Costa E, Oliveira, Pacheco C. Micro-RNAs: Current perspectives on the regulation of gene expression in eukaryotes. Biohealth, v. 2012; 14(2):81–93.