1. SDG Status and Perspectives in Serbia

As a relatively novel global strategy, SDGs in Serbia are well grounded in theory, but there is still a lot of continued effort in the long run for their achievement

[1]. The root of the problem is that many global solutions are difficult to scale down to the local level and exploited by a large number of practitioners. As a global concept, it can affect all levels of society at the same time; combined with advanced communication capabilities, it can increase the availability of ideas and solutions on the SDGs. This can ensure that a key aspect of sustainable development is met—the needs of future generations. However, a recent study conducted in the Western Balkans

[2] suggests that even the younger generation (14–30 years old) does not have an adequate understanding of the SDGs.

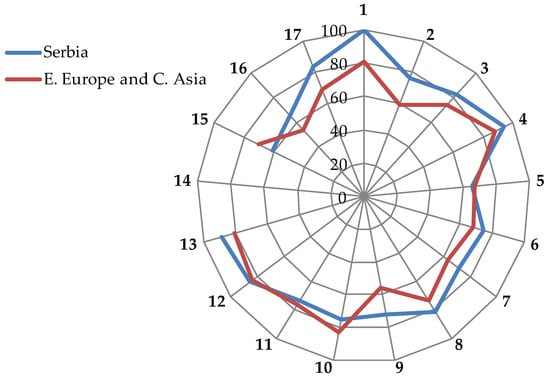

The overall score index measures a country’s total progress towards achieving SDGs. This index for Serbia in 2023 amounted to 77.3%. There is a stable but slow increase in the index score compared over time and compared to 2020 when the score was 71.22%. In 2023, the overall ranking of Serbia is 36 of a total of 166 Countries

[3]. A higher individual score for Serbia was obtained for 2 out of 17 goals, such as eradication of poverty (Goal 1) and quality of education (Goal 4). Significant challenges remain for Goals 5 and 10, while challenges remain for Goals 2, 3, 6, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13 and 16. It appears that a major obstacle for Serbia remains with Goal 15—life on the land. Of particular interest is the achievement of Goal 2 as an indicator that covers sustainable agriculture and food security issues (

Figure 1), which is gradually increasing in recent years. Serbia’s position in the context of SDG achievement can be compared to neighboring countries that encompass similar characteristics in terms of agriculture development and food production

[4][5]. The SDG ranking for Serbia is lower compared to Croatia (12), Hungary (22) and Romania (35) but the obtained results outperformed Bulgaria (44), Bosnia and Herzegovina (47), North Macedonia (60) and Montenegro (67) (

Table 1). It is also evident that the SDG achievement of Serbia in 2023 falls behind the region of East Europe and Central Asia, and this is particularly marked for Goals 1, 2, 3, 4, 9 and 17. It is noticeable that in the recent period, the number of indices for assessment of SDGs in Serbia increases, but collecting data also remains a challenging task, as unavailability for some of the SDG indicators presents a limitation for studying achievement toward SDGs

[5]. Therefore, future efforts should focus on better strategies in collecting data, in order to permit their wider application and understanding. Among the listed countries (

Table 1), a higher SDG index score was achieved in Croatia (81.5) and the lowest in Montenegro (71.5). Serbia has comparable results to those of neighboring countries listed in

Table 1 in terms of SDG index scores and spillover index, and so far holds a middle position.

Figure 1. Sustainable development goal achievement (0–100%) for 2023 of Serbia relative to East Europe and Central Asia countries

[3]. Numbers 1–17 indicate different SDGs.

Table 1. The sustainable development goals 2023

[3].

| Country |

SDG Indicators 2023 |

| Country Rank |

SDG Index Scores |

Spillover Index |

| Croatia |

12 |

81.5 |

75.8 |

| Hungary |

22 |

79.4 |

80.1 |

| Serbia |

36 |

77.3 |

86.6 |

| Romania |

35 |

77.5 |

81.7 |

| Bulgaria |

44 |

74.6 |

88.1 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina |

47 |

74.0 |

89.3 |

| North Macedonia |

60 |

72.5 |

90.8 |

| Montenegro |

67 |

71.4 |

77.2 |

| East Europe and Central Asia |

n.a. |

71.8 |

91.1 |

| EU27 |

n.a. |

72.0 |

63.8 |

There is a general public view that not much action has been taken in the preparation and increasing institutional capacity regarding the SDGs, but Serbia is on the way to aligning national policies with the United Nations Agenda for Sustainable Development by 2030. To comply with the requirement of the SDGs, the conference “How to Reach Sustainable Development in Serbia: UN Agenda 2030” initiated public debate and connected stakeholders from different sectors (

http://www.ciljeviodrzivograzvoja.net/, accessed on 1 December 2023). For a long time, progress towards achieving the SDGs has been slow, but in recent years we have seen an increase in the realization of SDGs as a result of interest in environmental issues and raised awareness about their importance. The progress report from 2022 indicated that Serbia is making progress towards the achievement of Agenda 2030 in several key areas in 43 indicators and showed a high degree of resilience to multiple stresses

[6]. But as seen from

Table 1, it is a long process that must involve all spheres of society. In assessing the socio-economic vulnerability of SDGs in Serbia, Matović and Lović Obradović

[7] identified three indicators: economically inactive population, population without primary education and gross added value per capita as major obstacles. Recent data showed a total of 76.6 million USD of investment in SDG achievement in Serbia to 92 ongoing activities, with unequal distribution to individual goals. The highest share of resources goes to SDGs 10, 11 and 16, while the lowest was allocated for SDGs 6, 1 and 7 (

https://serbia.un.org/en/sdgs, accessed on 1 December 2023). A recent publication, ′Thematic update sustainable food systems′, recommended a green transformation of the Serbian food system towards a more inclusive, sustainable and equitable growth model, which includes climate change mitigation and biodiversity loss

[8]. This shows a general interest in agriculture and its position on the list of priorities for the implementation of SDGs in Serbia, but there seems to be little support for those activities that are more closely related to agriculture and especially primary food production.

2. Contribution of Organic Agriculture to Sustainable Development in Serbia

Practical examples of different types of sustainable agricultural systems can be identified in Serbia, such as permaculture, biodynamic agriculture, regenerative agriculture, agroecology and organic agriculture, but there is also a significant overlapping between them. Although there is a high awareness and need to introduce ecological principles and sustainable intensification, so far, areas under the sustainable agriculture systems in Serbia occupy only a small land-use area; they are not adequately accepted by all farmers, and a significant part of the production is export-oriented

[9]. The fact is that many of these sustainable farming systems were firstly being adopted by NGOs, small farmers and, more recently, by large commercial companies. Various studies have confirmed that there is a positive attitude towards the consumption of products that come as a result of sustainable production

[10][11][12][13]. Organic farming can contribute to sustainable development by showing the model of production or being the lighthouse for sustainability. In other words, this may be the optimal model for achieving SDGs as the most widespread alternative system in Serbia. The advantage of organic agriculture is that there is traceability of production and a clearly defined system for both producers and consumers. As opposed to other sustainable systems, organic farming has been identified with distinctive objectives and a multifunctional approach; it takes up a larger area and is considered to be mainstream in terms of sustainability, compared to the other sustainable farming system for which data were not available. Also, due to seasonal migrations between Serbia and the countries of Western Europe, many consumer trends and habits that started in those countries are present in Serbia. It is important to mention that the pioneers of organic agriculture farming in Serbia were motivated by a desire to resolve long-standing problems of conventional production—environmental pollution, the decline in soil quality, biodiversity loss, lower food quality, nutrients and ubiquitous rural poverty

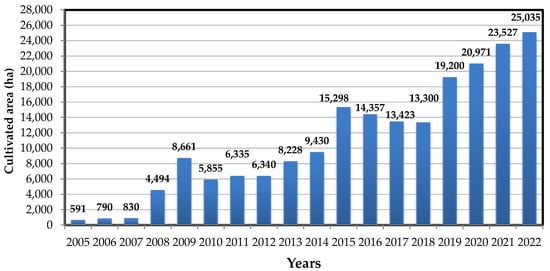

[14]. Today, the organic sector is successfully expanding and gaining in importance with respect to the raised awareness of safe food production and environmental protection. This has led to a balanced approach to organic farming and the development of specificities that are the result of agroecological preconditions and socio-economical background. Organic production in Serbia has been gradually developing for more than three decades

[14][15], but statistical monitoring dates back to 2005 (

Figure 2). At the same time, institutional and legal regulation in line with EU standards began. The review of the historical data of organic production in Serbia identified emerging trends and showed that many operators in the sector are trying hard to advance on the road defined by the Plan for Organic Agriculture Development in Serbia 2021–2026

[16]. This plan is a part of the National Rural Development Program of the Republic of Serbia, 2018–2020, which was adopted by the Government of the Republic of Serbia in 2018. This strategic program strongly supports the development of organic production in Serbia and identifies the challenges that impede its development and defines aims and measures to overcome them.

Figure 2 shows that the area under organic production has increased by roughly 30 times from the beginning and the number of producers by not as many times (

Figure 2,

Table 2). One of the weaknesses of the organic sector stems from the fact that, for a long time, the subsidy policy for organic agriculture in Serbia was not separated from conventional agriculture and therefore shared the same fate as conventional agriculture.

Figure 2. Changes in land area under organic agriculture in Serbia (source: MAFWM

[17]).

Table 2. Basic data of organic agriculture of Balkan countries according to Fibl survey 2023

[18].

| Country |

Indicators |

Years |

Relative Change 2010/2022 (%) |

| 2010 |

2012 |

2014 |

2016 |

2018 |

2020 |

2022 * |

| Hungary |

Organic area (ha) |

127.605 |

130.609 |

124.841 |

186.347 |

209.382 |

301.430 |

293.597 |

+230 |

| Producers |

1.557 |

1.560 |

1.672 |

3.414 |

3.929 |

5.128 |

5.129 |

+329 |

| Organic share (%) |

3.02 |

3.1 |

2.7 |

4.0 |

4.5 |

6 |

5.9 |

+195 |

| Bulgaria |

Organic area (ha) |

25.648 |

39.137 |

74.352 |

160.620 |

128.839 |

116.253 |

86.310 |

+453 |

| Producers |

717 |

2.754 |

3893 |

6.964 |

6.471 |

5.942 |

5.942 |

+828 |

| Organic share (%) |

0.84 |

1.3 |

2.4 |

3.5 |

3.5 |

2.3 |

1.7 |

+273 |

| Romania |

Organic area (ha) |

72.300 |

288.261 |

289.252 |

226.309 |

326.260 |

468.887 |

578.718 |

+800 |

| Producers |

2.986 |

15.315 |

14.159 |

10.083 |

8.518 |

9.647 |

11.562 |

+387 |

| Organic share (%) |

1.4 |

2.1 |

2.1 |

1.7 |

2.5 |

3.5 |

4.3 |

+307 |

| Croatia |

Organic area (ha) |

23.351 |

31.903 |

50.054 |

93.593 |

103.166 |

108.610 |

121.924 |

+522 |

| Producers |

1.125 |

1.528 |

2.194 |

3.546 |

4.374 |

5.153 |

6.024 |

+535 |

| Organic share (%) |

1.8 |

2.4 |

3.8 |

6.0 |

6.6 |

7.2 |

8.1 |

+450 |

| Serbia |

Organic area (ha) |

8.635 |

6.340 |

9.548 |

14.358 |

19.254 |

20.971 |

23.527 |

+272 |

| Producers |

224 |

202 |

215 |

286 |

373 |

439 |

458 |

+204 |

| Organic share (%) |

0.2 |

0.1 |

0.2 |

0.4 |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

+350 |

North

Macedonia |

Organic area (ha) |

35.164 |

12.731 |

3.146 |

3.245 |

4.409 |

3.727 |

7.794 |

−451 |

| Producers |

342 |

554 |

331 |

509 |

775 |

863 |

887 |

+259 |

| Organic share (%) |

3 |

3.3 |

1.19 |

1.3 |

0.3 |

0.3 |

0.6 |

−500 |

| Montenegro |

Organic area (ha) |

1.865 |

3.561 |

3.038 |

3.470 |

4.455 |

4.823 |

3.381 |

+181 |

| Producers |

25 |

62 |

62 |

280 |

328 |

423 |

422 |

+1688 |

| Organic share (%) |

0.36 |

0.69 |

0.6 |

1.5 |

1.9 |

1.9 |

1.7 |

+472 |

| Bosnia and Herzegovina |

Organic area (ha) |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

1.692 |

2.495 |

/ |

| Producers |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

90 |

/ |

| Organic share (%) |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

n.a. |

0.14 |

/ |

One of the preconditions for the development of sustainable agriculture is land availability, land policy and soil quality

[17]. Analyzing the areas used in agriculture according to the World Bank

[19], it can be seen that the countries of Eastern Europe (the Balkan Peninsula in general) lead in the share of land area used for agriculture. Romania has the largest share with 59% and Montenegro the smallest with 19%. Serbia has an average share of 40%, which is close to the EU27 average value, which amounts to 41%. These data are important because they can basically represent the potential for the development of organic agriculture in Serbia by taking the experience and capacities of conventional producers. The Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Water Management (MAWF)

[20] and the Group for Organic Agriculture, which is in charge of maintaining the database on organic agriculture, have provided data indicating that in the following years, both the number of producers and the organic area will continue to expand. Currently in Serbia, 0.6% of the arable land has been allocated for organic farming. Since Serbia lacks an established approach for gathering data on the total area utilized for collecting and harvesting plant species from their natural environment, this area does not include land used for the collection of wild berries, mushrooms and herbs

[15]. Since the beginning of organic development, Serbia’s organic producers have primarily been classified into two general groups or types: the independent producers who have direct contractual relationships with control bodies, and agricultural cooperatives whose production is subject to group certification, as permitted by Serbian law. When compared to individual farmers, this kind of collaboration has a considerably greater participation rate, which indicates its great success. However, the strategic approach should be focused on creating incentives for and cooperatives of the farmers at the regional level. In addition to that, the first biodistrict in Serbia was created to help sustainably manage local resources

[21]. This could be a step forward in the better articultaion of SDGs and organic agriculture.

The last decade also brought a more intensive development of the processing industry, domestic market and public consciousness, with the whole sector achieving significant results in export, about 29.7 million EUR, which proves the high demand for Serbian organic products both on the EU market and on other continents

[15][20]. However, compared with neighboring countries, Serbia showed a slower development regarding the area, in terms of number of producers and organic land share (%) (

Table 2). Considering the similar agroecological background of the Balkan countries, statistical data (2010–2022) indicate that only North Macedonia and Bosnia and Herzegovina showed a lower performance in some parameters compared with Serbia

[18]. The country of ex-Yugoslavia and the EU countries were ahead with all indicators, as well as positive trends in growth compared with Serbia. Therefore, taking into account the current tendency in Serbia, it would be difficult to expect a dramatic growth in the organic agriculture area and increase in the number of producers in the near future. This means that there are many challenges in Serbia that have not been successfully overcome or properly addressed since the introduction of organic agriculture as an alternative to conventional agriculture.

Organic farming has a great potential to grow in Serbia, despite its undeniably substantial accomplishments and favorable agroecological settings, but there are still a lot of critical challenges that need to be appropriately addressed. Creating capital at every stage of the value chain, making better use of foreign funding and improving the effectiveness of production, processing and marketing are all critical concerns that must be resolved as Serbia’s organic industry develops. To ensure the organic sector grows more intensively in the future, government policy must be more focused and must include clear, long-term, national initiatives that apply to all of society

[17][22]. The concept of sustainable agricultural and rural development could be successfully implemented in the future with proper institutional support and greater utilization of available funds

[23]. However, critics argue that, with organic agriculture, more area is needed to produce the same amount of food, and this expansion can only be achieved at the expense of areas allocated to nature, as explained in

[24]. There is a general belief that consumers who are concerned about food safety are more likely to buy organic food

[25]. According to Radojević et al.

[10], consumers in Serbia make decisions about whether or not to purchase organic products primarily based on price and product quality, which is influenced by their socioeconomic status. The results of the research

[26]. showed that organic food consumers in Serbia are more educated and have higher incomes. Thereby, eco-marketing should focus more on appealing to these already’more environmentally and health-conscious’ consumers, as this will help to improve the domestic market for organic products. In line with this, corresponding research in Serbia

[10][13] showed a degree of mistrust regarding “organic” products. Therefore, it is imperative to establish trust and reinforce the producer certification system institutionally to allay any concerns.

3. Synergies of Sustainable Development Paradigm and Organic Agriculture

The starting point for the expansion of the certified organic farming area in Serbia could be an idea that agriculture is not only about the activities and processes involved in producing food, but also about the environment, the people and institutions involved in producing, processing, delivering and ultimately consuming food

[27][28][29]. Therefore, it is necessary to take a closer look at the relationships that exist among players in the food system or value chains and to examine a broader context of agriculture and local agricultural heritage in the development of organic agriculture in Serbia. The legacies of traditional agriculture allow us to increase the multifunctional nature of organic agriculture as an important issue in the development of rural areas during the 21st century

[29].

At the moment, there is a weak link between organic farming and the SDGs in Serbia, both in practice and in the socio-economic domain. The assuption is that SDG implementation has the potential in organic agriculture to secure and accelerate innovation, knowledge transfer and economic growth

[30]. However, in order to effectively achieve the SDGs, it is essential to build on the work being done at the local scale

[29]. One of the obstacles to the poor link between organic agriculture and SDGs is that producers and consumers in Serbia recognize the sustainability concept as a purely ecological idea

[31]. The perspective of SDG 1 depends on the successful communication and real partnership between the government and the local authorities, and in some cases, this can result in the stagnation and even the involution of certain social categories of the population

[29]. The assumption is that ecology greatly underpins sustainable agriculture, relies on renewable resources and small-scale agroecosystems to create a self-sufficient food value chain. It is also a widely accepted idea that sustainable agriculture can be expanded with increased consumer requirements for healthy food consumption, and together they offer the possibility of a compromise between ecology, environmental protection and food security

[31][32]. The global narrative is that the sustainable agricultural system cannot provide a sufficient quantity of production of food and plant products for other technical purposes as well as achieving economic efficiency. However a range of such systems can successfully meet goals and interact with natural habitats, preserving basic natural resources and energy, and protecting the environment

[33]. Yet, Serbia has a considerable area with preserved natural resources, a large number of protected natural parks, small agricultural holdings and a relatively large number of farms, with extensive agriculture, especially in mountainous areas, where an underutilized environment has a higher potential for organic production

[11][15][27]. Although abundant natural resources can be a significant advantage, their accelerated exploitation is not recommended, as it can lead to significant impacts on the environment and have a negative impact on the achievement of SDGs. This is indicated by the research of Nzié and Pepeah

[34], which showed that countries that lag behind in achieving sustainability goals must be responsive to the use of natural resources. It is considered that a large part of the mountainous areas of Serbia is beyond the significant influence of intensive (conventional) agriculture and anthropogenic pressure. Agricultural production in these areas takes place without intensive agro-technical measures (mineral fertilizers and chemical means of protection), with diverse crop rotation, extensive self-sufficient livestock production and their own labor force. Therefore, organic agriculture would be very suitable as a way of managing natural resources in protected areas: national parks, nature reserves, water supply zones, landscape features and other vulnerable and endangered parts of Serbia. As a modern model of agricultural production, based on biological principles, organic farming can provide a broader range of rural activities by including various economic actions and providing financial benefits not just for the food production that ovelaps with SDGs

[35]. Encouraging organic production and integrating it with other production activities will preserve the diversity of rural performance and pave the way for the growth of multipurpose tourism, ecotourism and ethnotourism. Above all, it could create the conditions for people to stay in rural areas and establish small, self-sufficient farms. On the other hand, problems can hinder the exploitation of rural regions, the most important of which is the decline in population and the departure of young people from rural areas

[36][37].