Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Birgitte Andersen | -- | 4594 | 2024-02-21 14:32:08 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | + 56 word(s) | 4650 | 2024-02-23 04:36:11 | | | | |

| 3 | Lindsay Dong | Meta information modification | 4650 | 2024-02-29 07:30:58 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Loukou, E.; Jensen, N.F.; Rohde, L.; Andersen, B. Building Associated Fungi and How to Find Them. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/55306 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Loukou E, Jensen NF, Rohde L, Andersen B. Building Associated Fungi and How to Find Them. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/55306. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Loukou, Evangelia, Nickolaj Feldt Jensen, Lasse Rohde, Birgitte Andersen. "Building Associated Fungi and How to Find Them" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/55306 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Loukou, E., Jensen, N.F., Rohde, L., & Andersen, B. (2024, February 21). Building Associated Fungi and How to Find Them. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/55306

Loukou, Evangelia, et al. "Building Associated Fungi and How to Find Them." Encyclopedia. Web. 21 February, 2024.

Copy Citation

The number of buildings experiencing humidity problems and fungal growth appears to be increasing as energy-saving measures and changes in construction practices and climate become more common. Determining the cause of the problem and documenting the type and extent of fungal growth are complex processes involving both building physics and indoor mycology. The most reported building-associated fungi across all materials are Penicillium chrysogenum and Aspergillus versicolor. Chaetomium globosum is common on all organic materials, whereas Aspergillus niger is common on all inorganic materials.

fungal growth

building materials

indoor mycobiota

water damage

Penicillium chrysogenum

Aspergillus versicolor

Chaetomium globosum

1. Introduction

Prolonged indoor exposure, prevalent in industrialised countries, significantly impacts the comfort, health and well-being of individuals [1]. The growth of fungi and bacteria in the humid or wet built environment is one of the key issues of indoor air contamination [2][3] and plays an essential role in occupational and public health problems [4][5]. Indoor mould has been associated with adverse health effects [2][4][6][7][8].

Increased humidity is the most critical factor for indoor fungal growth [2][3][9][10]. Fungal growth in damp buildings is a common problem due to condensation on interior surfaces, water damage from burst pipes or flooding. Furthermore, increased indoor humidity can cause damage to the building construction and materials [11][12] and triggers chemical emissions [13].

Even though fungal spores are ubiquitous, not all fungal species can grow everywhere [14]. Buildings constitute new habitats for fungi to grow and proliferate [4][15][16][17]. These artificial, inorganic environments have different characteristics than natural habitats that fungi have occupied for millions of years [16]. Therefore, the fungal biodiversity indoors is distinct and limited compared to the natural habitats they originate from. While fungal spores can be introduced indoors from various sources such as the soil, food products, potted plants, pets and humans [18], as well as from building materials themselves [19][20], the predominant and primary source is the outdoor air [21].

Not all building materials are equally susceptible to fungal growth. The characteristics of the building material and its moisture content determine which species can grow on it [4] and which mycotoxins and other metabolites will be produced and released into the indoor environment [22][23]. The composition and availability of organic compounds are also critical factors for the suitability of materials to serve as a nutrient source [24]. Consequently, different materials are prone to be colonised by specific fungal species, contingent on the fortuitous deposition of the fungal spores on the designated material and the alignment of moisture level and nutrient composition with the fungus’ needs [4][14][19][25].

The demand to increase energy savings in the built environment has led to new construction techniques and increased airtightness of the building envelope. However, if these measures are not properly designed and implemented, there is a high risk of moisture increase indoors, condensation on the internal surfaces and thus, fungal growth [26]. The combination of highly insulated external walls and inadequate ventilation due to faulty design, installation, operation or maintenance is the main reason for fungal contamination in low-energy buildings [27][28].

Furthermore, fungal contamination of buildings has also a socioeconomic aspect, as it is connected to poor housing conditions, fuel poverty and energy crises [29]. Fungal problems are more common and severe in low-income communities due to the lack of maintenance, insulation, ventilation and heating of buildings [2]. Additionally, indoor space overcrowding leads to increased moisture production that does not correspond to the original mechanical ventilation rates [30].

Sampling, detecting and identifying fungi are important aspects of controlling and preventing fungal growth in the built environment when water damage has occurred. There exists a broad variety of sampling techniques and detection methods but no specific procedures, guidelines or standards for how they should be carried out. Therefore, the results of a building inspection are often not reproducible. Different inspectors may reach different conclusions on the severity, extent and remediation measures for the fungal growth and the building. Each sampling technique has advantages and limitations, while factors like the sampling location significantly affect the outcome of the analysis [17].

Detection of fungal growth in a moisture-damaged building without species identification is not sufficient to address and solve the problem effectively. Different fungal species have different requirements even though they belong to the same fungal genus. Genera like Alternaria, Aspergillus and Penicillium are commonly encountered in the indoor air and dust, but different species have different origins. Some species are food-borne (baseline spora) (e.g., Penicillium digitatum on citrus fruit), whereas others are associated with building materials (indicator species) (e.g., P. chrysogenum on wallpaper) [14][17][31][32].

2. Requirements for Fungal Growth

Fungi’s life cycle includes three phases: (1) spore germination, (2) mycelium growth and (3) spore formation (sporulation). During the first two phases, vegetative growth takes place, while the third phase consists of the fungus’ reproduction [10]. When the environmental conditions are right, the fungal spores that have settled on the different surfaces start germinating. A mycelium is produced, a multi-cellular filamentous structure, to allow food intake. Fungi secrete extracellular enzymes and acids, which break down the growth medium/substrate to access the nutrients they need [33]. During this process, particles, gases and microbial volatile organic compounds (MVOCs) are released into the environment. After the mycelium has grown enough, spores are created from the fruiting bodies, while the mycelium continues growing to produce more spores and ensure further spreading of the microorganism in its habitat. As nutrient availability decreases, the fungus’ life is endangered, and so sporulation increases to ensure its survival and further propagation [10]. Thus, spore diffusion is relatively independent of the growth conditions.

2.1. Abiotic Factors for Fungal Growth

2.1.1. Temperature

Fungi can tolerate a wide range of temperatures, from 0 to 50 °C [10][34]. However, their optimal temperature range for growth is narrower, as fungi enter a dormant state at low temperatures of 0–5 °C by slowing down their metabolic activities, while most fungal species die at high temperatures above 46 °C [33]. Most building-related fungal species have a temperature optimum between 20 and 25 °C [31], which coincidentally is also the desired temperature range in buildings for thermal comfort.

2.1.2. Moisture Content, Water Activity or Relative Humidity

Several factors describe the state of water in materials, i.e., water activity, osmotic pressure, fugacity, water potential and water content [35]. As fungi mostly grow on surfaces, they utilise unbound, available water on the surface of the substrate (i.e., the building material), not what is trapped inside it [35][36]. The water activity (𝑎𝑤)

of surfaces can be used to directly assess the moisture availability for fungal growth [35][37]. The material’s moisture content is another useful factor, while the air relative humidity (RH) only affects the moisture level indirectly [38]. The 𝑎𝑤 refers to the ratio of the vapour pressure of pure water in the material to the vapour pressure of pure water at the same conditions of temperature and pressure [21] (𝑎𝑤 × 100 = % RH at equilibrium) [32]. Every fungus has specific moisture requirements, meaning it has a minimum, a maximum and an optimum 𝑎𝑤 for growth. Although the minimum 𝑎𝑤 may differ from species to species, the optimum level typically ranges between 0.90 and 0.99 [21][39].Often, the fungal growth rate (mm/d) or germination time (d) is plotted as a function of temperature and relative humidity/water activity (isopleth systems). These graphs are species-specific, based on the fungus’ growth requirements. Isopleths provide useful information on the influence of environmental conditions on the growth of fungi. However, they are developed under well-defined, steady-state conditions, which is rarely the case in practice.

The growing medium has an influence, mainly due to its 𝑎𝑤, on species detection and enumeration. Furthermore, the use of different standard media can serve for species identification, as the fungal colonies/conidia colour is determined by the media composition and added trace metals [31]. Finally, the different media are complemented with antibiotics to suppress the contamination of the cultures from bacteria [31].

Based on their moisture requirements, fungi are divided into groups: hydrophilic, mesophilic and xerophilic [25]; the grouping into primary, secondary and tertiary colonisers [38][40][41] has become obsolete since water damage is not necessarily a progression. Between mesophilic and xerophilic fungi, a group for xerotolerant fungi can be added [42]. It is well documented that the most important factor dictating fungal growth on building materials is the moisture availability [3][10][33][34][35][43][44], as dust and dirt that can serve as nutrient sources usually are present in all houses [2][13].

Furthermore, the duration of moisture exposure or time-of-wetness (TOW) [9] and the time of wet–dry cycles under fluctuating conditions are also important factors. Pasanen et al. [44][45] examined the spores’ behaviour under fluctuating conditions of temperature and relative humidity and suggested the hypothesis that conidia may be able to adapt to an unstable environment to survive [45] (Table 1).

Table 1. Minimum water activity (𝑎𝑤) requirements of representative fungal species.

| 𝒂𝒘 [References] | Genus | Species | Media [References] | |

| Hydrophilic | 0.95 [46][47] | Acremonium | charticola | V8 [47]; MEA [48] |

| 0.94–0.95 [21][47][49] | Stachybotrys | chartarum | V8 [14]; MEA [31] | |

| 0.94 [47][48] | Chaetomium | globosum | V8 [14]; MEA [31] | |

| 0.92 [47][48] | Rhodotorula | mucilaginosa | MEA [31] | |

| 0.90–0.95 [47][48][50] | Trichoderma | viride | V8 [47]; MEA [48] | |

| Mesophilic | 0.89–0.90 [40][48] | Alternaria | chartarum | V8 [14] |

| 0.86–0.91 [21][48] | Epicoccum | nigrum | V8 [14] | |

| 0.85–0.89 [21][40][47][48] | Alternaria | alternata | V8 [47]; DG18 [31] | |

| 0.85–0.88 [21][47][51] | Cladosporium | herbarum | V8 [14]; MEA, DG18 [31] | |

| 0.84–0.87 [21][40][47][51] | Cladosporium | cladosporioides | V8 [14]; MEA, DG18 [31] | |

| 0.82–0.85 [21][39][47] | Aspergillus | fumigatus | MEA, DG18 [31] | |

| 0.82–0.84 [40][47][48][51] | Cladosporium | sphaerospermum | V8 [14]; MEA, DG18 [31] | |

| 0.80 [48] | Penicillium | corylophilum | MEA, DG18 [31] | |

| Xerotolerant | 0.79–0.80 [21][48] | Paecilomyces | variotii | MEA, DG18 [31] |

| 0.78–0.85 [21][40][47][48][50] | Penicillium | chrysogenum | MEA, DG18 [31] | |

| 0.77–0.78 [39][47][48] | Aspergillus | niger | V8 [52]; MEA, DG18 [31] | |

| 0.74–0.79 [21][40][47][53] | Aspergillus | versicolor | V8 [14]; MEA, DG18 [31] | |

| 0.78 [21][48] | Aspergillus | sydowii | MEA, DG18 [31] | |

| Xerophilic | 0.69 [21][47][48] | Wallemia | sebi | DG18, MY50G [31] |

| 0.68 [54] | Aspergillus | halophilicus | MY50G [52] | |

| 0.59 [55] | Aspergillus | penicillioides | DG18, M40, M40Y [31][56] |

2.2. Composition and Properties of Building Materials

The characteristics of the building material serving as substrate play an essential role in the appearance of fungal growth and species diversity. The material’s surface structure, hygroscopicity, porosity, water permeability, etc., directly affect moisture availability. Different materials have varying moisture sorption capacity [12]. For instance, plywood, OSB and gypsum board are hygroscopic, meaning they tend to absorb moisture, thereby increasing their susceptibility to fungal growth [15][57][58]. In contrast, glass, ceramic products, polymer-based materials, etc., are hydrophobic and thus more mould-resistant [15][25][59].

The composition of building materials determines the nutrient availability on its surface, which is a key driver for the material’s susceptibility to fungal growth and abundance. When the environmental conditions are favourable for fungal germination, fungi diffuse enzymes into the substrate in order to break down the required nutrients, which can be used for their growth [17]. Building materials have distinct compositions and contain different organic compounds, which can be a good nutrient source for most fungi or just for specific species that can utilise them. Such components can be low molecular weight carbohydrates (e.g., glucose, dextrose), free sugars, natural organic polymers (e.g., starch, pectin, cellulose, hemicellulose, lignin, etc.) or other readily accessible nutrients [15][21][57]. For example, materials rich in organic matter, e.g., wood, plywood, the paper layer of gypsum board, ceiling tiles, etc., are especially good substrates due to their complex polymers [12][15][33][60][61]. On the other hand, paper-free materials or materials with lime composition (e.g., inorganic ceiling tiles, gypsum, etc.) are less susceptible to mould formation [15][60][62].

2.3. Characteristics of Building-Associated Fungal Species

Fungi have developed mechanisms that allow them to access their necessary nutrients [63]. The several different fungal species on a material interact with each other, which can create mutually beneficial or competitive relations. The growing fungi metabolise the components of the material and produce new nutrients that become available for other microbial organisms to use and proliferate in succession [17]. On the other hand, some species can produce toxins to inhibit other organisms (e.g., metabolites against bacteria) with the same growing requirements so they can claim the material [17]. The resulting metabolic products like allergens and toxins are related to the components and nutrients provided by the substrate and the species acting as colonisers [4][18][41][64][65][66][67].

3. Associated Fungi of Common Building Materials

3.1. Wood and Woodchip Materials

The first group of building materials consists of wood, either massive or composed of different sizes of woodchips and different levels of processing. Massive wood is a natural material comprising structural polymers, i.e., cellulose fibres, hemicellulose and lignin, and non-structural constituents called extractives. In contrast, woodchip-containing materials are engineered products manufactured by bonding woodchips by using adhesives (such as resins or glues) or compressed under heat and pressure. Materials like particleboard, OSB, medium-density fibre (MDF), chipboard, plywood, Masonite board, etc., are included in this subcategory.

3.2. Gypsum Board, Paper/Cardboard and Wallpaper

The second group also contains wood-based materials, in which the wood has been heavily processed, and consists of wood fibres. Gypsum board has a core of gypsum, which is a naturally occurring mineral composed of calcium sulfate dihydrate and paper finishes on both sides. Due to the paper, gypsum board, together with acoustic and ceiling tiles that have a similar composition, are grouped as organic materials. Paper and cardboard are listed together, as they are both manufactured from processed wood pulp. Even though wallpaper can be made from various materials such as paper, fabric or vinyl, this table specifically addresses wallpaper derived from wood pulp. Wood pulp is produced by mechanically or chemically breaking down cellulose fibres, which are then formed into sheets. The key differences between them lie in thickness, layering, surface treatment or the use of certain additives to enhance specific properties depending on their intended use.

3.3. Paint, Plaster, Concrete and Fibreglass Wallpaper

The third group includes inorganic materials with different primary components and distinct applications. Paint is a mixture of pigments, binders, solvents and additives for surface decoration. Plaster is composed of materials like gypsum, lime or cement and has usually a high pH value. Concrete is made with cement, water and aggregates to construct building elements. Finally, fibreglass wallpaper consists of woven fibreglass strands coated with a resinous binder for reinforcement or decoration of interior wall surfaces.

3.4. Insulation Materials: Bio-Based, Foam-Based, Mineral-Based

The last group contains insulation materials with different compositions. Bio-based insulation is made from renewable, organic resources. Foam-based insulation contains polymers and chemicals, which result in lightweight, rigid or flexible materials (e.g., Polyurethane, Polyisocyanurate, Polystyrene, Polyethylene, etc.). Mineral-based insulation materials are derived from naturally occurring minerals (e.g., Rockwool, Fibreglass, etc.). Each type of these materials has unique properties and is suitable for specific applications.

3.5. The Building-Associated Fungal Species

Materials, partly or totally organic, could support the growth of 102 different species, while on the inorganic materials, 70 different species were found. A total of 40 species were common to both organic and inorganic materials, with species like A. alternata, C. sphaerospermum, P. variotii and P. corylophilum being the most reported. Other species like A. glaucus and C. globosum were only found on organic materials, while A. charticola and M. spinosus only on inorganic materials.

4. Building Evaluation Process

Visible fungal growth on interior surfaces, furniture and other household effects is the most common reason for starting an investigation. However, often, an investigation is launched even in the absence of visible fungal growth because the occupants or building users experience mouldy odours and/or adverse health effects. An investigation can also be initiated before the renovation of a water-damaged building, e.g., due to flooding or another water-damage incident. Regardless, high humidity or water ingress is always the reason for the presence of fungal growth even though the source of water is not obvious or the building has dried out.

The purpose of an inspection is to ascertain the existence of fungal growth, to locate the source of humidity/water and to design a remediation plan. Knowing which fungal species are growing on a particular material and the preferred 𝑎𝑤

of the fungal species can ensure that all fungal growth is discovered and the correct renovation strategy is proposed [17].

To assess the building-related fungal contamination risk and confirm any moisture problems, it is necessary to quantify the fungal load, identify the microbial diversity and determine the contamination source. The assessment procedure is performed in four phases: (1) physical inspection of the building, (2) sample collection, (3) fungal detection and identification and (4) evaluation report. Figure 1 depicts this process and potential steps.

Figure 1. Fungal contamination assessment process of damp buildings.

Fungal growth can be seen in buildings as discolouration, stains or blots on walls, floors and ceilings, especially on colder surfaces like thermal bridges, below windows, behind furniture, etc. When fungal growth is visible, the procedure is straightforward: to clean off/demolish the affected area, restore it and perform quality control. However, fungal growth can also be hidden in the building construction, cavities and behind the wallpaper or sit in plain sight but be colourless, thin and patchy, thus easily overlooked.

All fungal growth, visible or unseen, can release equally high concentrations of fungal particles in the indoor environment [68], and it can be recognised through high humidity, musty odours or complaints of negative health symptoms by the occupants. Nonetheless, it can be challenging to find and sample, while restoration can be costly. Therefore, it is estimated that there is significant under-reporting of these cases. The microbial assessment of damp and mouldy buildings is an interdisciplinary challenge, spanning across the fields of mycology, building science and public health [69].

There are various sampling techniques that can be used for sample collection, while different detection methods can be applied to the collected samples. Some samples can be analysed by several detection methods, while others are intended for specific analysis. In the following sections, the sampling techniques and detection and identification methods are first analysed independently. Subsequently, it is described how the sampling techniques can be paired with the commercially used detection and identification methods.

4.1. Physical Inspection

A thorough walk-through inspection of the building is pivotal. Through the visual inspection, the investigator can reveal evidence of current or past water ingress, detect critical/problematic areas with humid or mouldy spots and evaluate the mouldy odour, which can be indirect evidence of hidden fungal growth. For that, investigators need to have a broad knowledge of moisture transport in buildings, material properties and behaviour and be able to identify the potential areas for increased or concealed humidity [17].

The inspection can be combined with a survey/questionnaire for the occupants about the experienced indoor air quality, possible symptoms or health problems related to fungal growth, their daily airing routines, cleaning practices, heating, ventilation and air conditioning (HVAC) system and the type and state of the building (e.g., past water damage incidents, insulation level, renovation works, etc.).

4.2. Sample Collection

4.2.1. Material Sampling

Sampling of visible fungal biomass directly where it grows is the first and most obvious choice to characterise the fungal contamination of a building. Material sampling techniques are normally used for genus or species identification. A surface sample can be taken to determine whether a stain is caused by fungal growth or another issue [70][71] or the effectiveness of remediation measures [64].

Smaller parts of building material/construction (bulk samples) or larger parts of surfaces (scrapings and shavings) can be removed for analyses in the laboratory [17]. Surfaces can also be sampled and tested for fungal growth using contact plates (for cultivation), sterile swabs (for cultivation or enzymatic analysis) [72] or tape lifts (for microscopy), which is relatively economical and quick [73]. The tape-lift method can be used to complement culture or enzymatic methods.

4.2.2. Dust Sampling

Settled dust, 3 to 6 months old, can be a good proxy for either hidden fungal growth or for evaluation of long-term exposure of occupants to fungal particles. Dust sampling can be performed using sterile swabs, dust fall collectors (DFCs) or electrostatic dust fall collectors (EDCs) for long-term collection. Swab samples (usually 10 cm2) are obtained from horizontal surfaces 1.5 m or more above floor level on places that are not cleaned regularly, like on top of doors or picture frames, curtain rails, bookcases or cupboards [14]. As DFCs (usually 60–100 cm2), an empty, sterile Petri dish without medium can be used [69] or even a cardboard box with aluminium foil-covered inner surfaces [74]. Using the DFC method, airborne dust and fungal particles can be sampled over hours, days, weeks or even months, depending on the aim of the study [75]. EDCs [17][69][74][76] have been mostly used for exposure studies to endotoxins [76]. Floor dust, 1 to 3 weeks old, can also be sampled using a nozzle with micro-vacuum cassettes attached to an ordinary vacuum cleaner [71][77] or by analysing directly the dust collected from an ordinary vacuum cleaner bag (usually the whole living area) [78] and used to identify the present fungal particles [47][79].

4.2.3. Air Sampling

Air sampling provides a short-term exposure assessment through the collection of airborne fungal biomass. It can be done either passively (sampling over time) or actively (volumetric sampling). Passive air sampling is normally performed using Petri dishes containing growth medium, exposing the agar surface to the air for 30–60 min [65]. Active air sampling is carried out by using a device (sampler) drawing in a predefined volume of air. The most commonly used air sampling devices are (1) impactors and sieve samplers, (2) impingers, (3) filter samplers and (4) centrifugal and cyclonic samplers [17][80][81]. Impactors and sieve samplers collect a fixed volume of air impacted onto a Petri dish with growth medium or an adhesive surface (i.e., glass slides or membranes coated with a transparent, sticky substance). Centrifugal and cyclonic samplers use circular flow patterns to increase the airflow and deposit the airborne particles into a liquid, semi-solid or solid growth medium [80].

4.2.4. Choice of Sampling Techniques

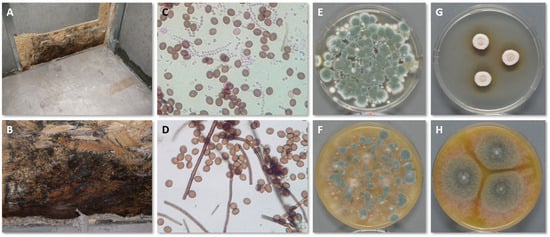

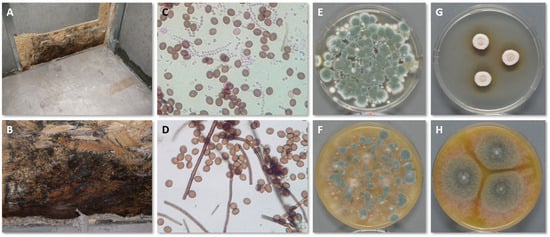

During the sampling process, several parameters and choices can affect the outcome of the investigation, and they must be considered in advance. In most cases, the purpose of the inspection dictates this decision-making process. Figure 2 shows the growth of C. globosum in the interface between OSB and gypsum wallboard (which has been removed) following a basement flood together with tape lifts, air samples on Petri dishes and pure cultures for identification.

Figure 2. Growth of C. globosum in the interface between OSB and gypsum wallboard (A,B). Tape lifts from the OSB and direct microscopy mostly reveal C. globosum (D), but some Penicillium conidia in chains are also present (C). Active air sampling onto DG18 (E) and V8 (F) show mostly Penicillium spp. because the conidia of C. globosum do not become as airborne as Penicillium conidia. Pure cultures of C. globosum on DG18 (G) and V8 (H) also show its hydrophilic nature by better growing on V8 than DG18.

The air sample volume determines the concentration of biomass that can be detected and is dictated by the sampling time and airflow rate [17][82][83]. The sampling time can vary greatly, from minutes to months, based on the selected sampling method and the needs of the investigation. The exact sampling location is important, especially for dust sampling, as the proximity to the source of fungal growth affects the concentration of spores [14].

4.3. Fungal Detection and Identification

Detection and identification methods concern the laboratory analyses of the collected samples to confirm the presence of fungal contaminants, estimate the fungal load and/or perform species identification. The analysis can be quantitative, assessing the amount of fungal biomass, or qualitative, listing the identity of the different fungal species. Samples can be analysed using microscopy, cultivation or molecular methods for identification and chemical/enzymatic methods for biomass determination.

4.3.1. Direct Microscopy

Using a dissecting or stereo microscope (×40 magnification), fungal growth can be observed directly on bulk materials, scrapings or shavings. For tape lifts, either directly from the fungal-infested materials or the bulk materials, scrapings or shavings, a light microscope (×400 magnification) is used. When performing microscopy analysis directly on the material, identification can typically be carried out to genus level only, while its use is limited in highly contaminated sites or samples due to overloading [84]. There is no need for an incubation period, and samples can be analysed directly, making this method low-cost and fast. On the other hand, there are no protocols and guidelines for the analysis, and identification demands a skilled mycologist. Therefore, it is not possible to standardise the processes between different laboratories [17].

4.3.2. Culture-Based Analysis

Traditionally, the most-used method has been culture-based analysis. It can be applied to most sample sources and types, while it can be used for species identification. On the other hand, it is time- and labour-intensive and requires skilled mycologists for correct species identification. For culture analysis, spores, fungal fragments or microparticles are collected and cultivated in different media in the laboratory under controlled conditions. The media selection and growing conditions are of great importance to the outcome of the analysis. Each cultivation medium favours specific genera and species, and it is, therefore, necessary to use a variety of media (e.g., DG18, V8, MEA) to cover the whole spectrum of indoor fungi [43]. Even the selected technique to introduce the sampled organic matter in the Petri dish (e.g., scattering, shaking, direct or dilution plating) can influence the growth rate and detected species [17][85].

4.3.3. Molecular Analysis

Molecular analysis of fungal biomass by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) or next-generation sequencing (NGS) has been gaining popularity in recent years, as it can provide quantitative results of high specificity, precision and sensitivity [72][84][86]. Culture-independent methods can detect both viable and most non-viable fungal fragments. The method has a fast analysis turnaround, and identification does not require highly trained mycologists. There are two approaches to molecular diagnostics, qPCR assays (commercial use) are designed to detect targeted, known species, while NGS (research use) provides higher discovery power to identify any species present [87].

4.3.4. Enzymatic/Chemical Analysis

Finally, chemical tests use surrogate markers [88] detecting specific proteins, enzymes or other organic compounds. Usually, these tests provide an assessment of the indoor microbial load. A widely used commercial method for the built environment is the 𝛽-N-acetylhexosaminidase (NAHA) enzyme test, which assesses the indoor microbial load [89]. The test has been developed for both surface and air sampling and lies in the detection of the NAHA enzyme [90].

4.3.5. Other Methods

There is a plethora of studies that have investigated the use of MVOCs and ergosterol, which could be used as biological markers [22][23][67][77][91]. For example, the particulate (1→3)-𝛽-D-Glucan is a carbohydrate that has been extensively researched as a measure of fungal biomass [17][22][75][92]. However, no commercial methods are available yet for assessing indoor environmental contamination due to the difficulty of determining the emission source [77].

4.3.6. Choice of Analytical Methods

All methods have strengths and weaknesses, and at present, no single method can be used to reliably confirm whether there is moisture or microbial damage [52][69][86][93]. Culture-dependent methods are highly selective due to the growing conditions, medium properties and the fact that heavy spore-producing, tolerant or general species are overestimated as they outgrow predominantly mycelial taxa and slow-developing, more fragile or specialised fungi [17][85]. In addition, spores’ viability is species-specific [17]. Molecular analysis can detect non-viable spores and fragments that cannot grow in a culture. That information can provide long-term insight, for example, about older water damage incidents that might have dried out or dead spores coated in toxins that might still be present, as spores and fragments can be allergenic despite their culturability [14][17]. On the other hand, culture methods do not require special equipment; they are widely used, well characterised and extensively researched and reliable reference data are available [84].

4.4. Evaluation Report

After the completion of the investigation, the outcome of the inquiry needs to be reported and communicated to the building owner and occupants. The results must be interpreted, and their significance explained in layman’s terms. It is fundamental that the report states the source and cause of moisture, a plan for repair and a risk assessment. The report should also contain all investigation steps with photo documentation, a description of the performed analyses and procedures, analyses’ results and conclusions. Finally, an action plan for the renovation of the building should be provided, including means to remove the fungal growth, a cleaning scheme and quality control of fungal removal.

5. Conclusions and Perspectives

Overall, the literature highlights the challenges of investigating the existence of fungal growth. At the same time, a targeted approach is often needed where the inspector knows which species to look for [52][69]. Focusing on specific fungal groups and species likely to grow in damp indoor environments and on the present, specific building materials can help, for example, to choose the suitable medium for isolation or adequate detection method. In addition, research has shown that the production of mycotoxins is species-specific [65] and the substrate and its characteristics influence their production [66]. Therefore, a better understanding of the associations between fungal species and various construction materials can be employed to limit adverse health effects stemming from exposure to building-related fungal species, as well as reduce material decay [15]. Nevertheless, standardised, widely accepted protocols and guidelines are missing [69][71][80][88], making it difficult to obtain reproducible and comparable results, as well as definite recommendations on fungal contamination problems.

References

- Rohde, L.; Larsen, T.S.; Jensen, R.L.; Larsen, O.K. Framing holistic indoor environment: Definitions of comfort, health and well-being. Indoor Built Environ. 2020, 29, 1118–1136.

- WHO Guidelines for Indoor Air Quality: Dampness and Mould; WHO Regional Office for Europe: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2009.

- Yang, C.S.; Heinsohn, P.A. Sampling and Analysis of Indoor Microorganisms; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2007.

- Miller, J.D. Fungal bioaerosols as an occupational hazard. Curr. Opin. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2023, 23, 92–97.

- Ghodrati, N.; Samari, M.; Shafiei, M.W.M. Green buildings impacts on occupants’ health and productivity. J. Appl. Sci. Res. 2012, 8, 4235–4241.

- Bornehag, C.G.; Blomquist, G.; Gyntelberg, F.; Järvholm, B.; Malmberg, P.; Nordvall, L.; Nielsen, A.; Pershagen, G.; Sundell, J. Dampness in buildings and health. Nordic interdisciplinary review of the scientific evidence on associations between exposure to “dampness” in buildings and health effects (NORDDAMP). Indoor Air 2001, 11, 72–86.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Damp Indoor Spaces and Health. Damp Indoor Spaces and Health; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2004.

- Mendell, M.J.; Mirer, A.G.; Cheung, K.; Tong, M.; Douwes, J. Respiratory and allergic health effects of dampness, mold, and dampness-related agents: A review of the epidemiologic evidence. Environ. Health Perspect. 2011, 119, 748–756.

- Adan, O.C.G.; Huinink, H.P.; Bekker, M. Water relations of fungi in indoor environments. In Fundamentals of Mold Growth in Indoor Environments and Strategies for Healthy Living; Adan, O.C.G., Samson, R.A., Eds.; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2011; pp. 41–65.

- Sedlbauer, K. Prediction of Mould Fungus Formation on the Surface of and Inside Building Components. Ph.D. Thesis, Fraunhofer Institute for Building Physics, Stuttgart, Germany, 2001.

- Kazemian, N.; Pakpour, S.; Milani, A.S.; Klironomos, J. Environmental factors influencing fungal growth on gypsum boards and their structural biodeterioration: A university campus case study. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0220556.

- Mensah-Attipoe, J.; Reponen, T.; Salmela, A.; Veijalainen, A.M.; Pasanen, P. Susceptibility of green and conventional building materials to microbial growth. Indoor Air 2015, 25, 273–284.

- Du, C.; Li, B.; Yu, W. Indoor mould exposure: Characteristics, influences and corresponding associations with built environment—A review. J. Build. Eng. 2021, 35, 101983.

- Andersen, B.; Frisvad, J.C.; Dunn, R.R.; Thrane, U. A pilot study on baseline fungi and moisture indicator fungi in danish homes. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 71.

- Zhao, D.; Cardona, C.; Gottel, N.; Winton, V.J.; Thomas, P.M.; Raba, D.A.; Kelley, S.T.; Henry, C.; Gilbert, J.A.; Stephens, B. Chemical composition of material extractives influences microbial growth and dynamics on wetted wood materials. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14500.

- Kelley, S.T.; Gilbert, J.A. Studying the microbiology of the indoor environment. Genome Biol. 2013, 14, 202.

- Hung, L.L.; Caulfield, S.M.; Miller, J.D. (Eds.) Recognition, Evaluation, and Control of Indoor Mold, 2nd ed.; American Industrial Hygiene Association: Falls Church, VA, USA, 2020.

- Nevalainen, A.; Täubel, M.; Hyvärinen, A. Indoor fungi: Companions and contaminants. Indoor Air 2015, 25, 125–156.

- Andersen, B.; Dosen, I.; Lewinska, A.M.; Nielsen, K.F. Pre-contamination of new gypsum wallboard with potentially harmful fungal species. Indoor Air 2017, 27, 6–12.

- Andersen, B.; Smedemark, S.H.; Jensen, N.F.; Andersen, H.V. Forsegling af Skjult Skimmelsvampevækst/Sealing of Hidden Fungal Growth; BUILD Rapport Nr. 2022:11; Institut for Byggeri, By og Miljø (BUILD), Aalborg Universitet: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022.

- Flannigan, B.; Samson, R.A.; Miller, J.D. Microorganisms in Home and Indoor Work Environments: Diversity, Health Impacts, Investigation and Control, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2011.

- Seo, S.C.; Reponen, T.; Levin, L.; Borchelt, T.; Grinshpun, S.A. Aerosolization of particulate (1→3)-β-D-glucan from moldy materials. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 585–593.

- Wilkins, K.; Larsen, K.; Simkus, M. Volatile metabolites from mold growth on building materials and synthetic media. Chemosphere 2000, 41, 437–446.

- Jensen, N.F.; Bjarløv, S.P.; Rode, C.; Andersen, B.; Møller, E.B. Laboratory-based investigation of the materials’ water activity and pH relative to fungal growth in internally insulated solid masonry walls. Indoor Air 2021, 31, 1252–1266.

- Hyvärinen, A.; Meklin, T.; Vepsäläinen, A.; Nevalainen, A. Fungi and actinobacteria in moisture-damaged building materials-Concentrations and diversity. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2002, 49, 27–37.

- Di Giuseppe, E. Nearly Zero Energy Buildings and Proliferation of Microorganisms; SpringerBriefs in Applied Sciences and Technology; Springer: Cham, Germany, 2013.

- Carpino, C.; Loukou, E.; Austin, M.C.; Andersen, B.; Mora, D.; Arcuri, N. Risk of fungal growth in Nearly Zero-Energy Buildings (nZEB). Buildings 2023, 13, 1600.

- Niculita-Hirzel, H.; Yang, S.; Jörin, C.H.; Perret, V.; Licina, D.; Pernot, J.G. Fungal contaminants in energy efficient dwellings: Impact of ventilation type and level of urbanization. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 4936.

- Couldburn, L.; Miller, W. Prevalence, risk factors and impacts related to mould-affected housing: An Australian Integrative Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 1854.

- Ginestet, S.; Aschan-Leygonie, C.; Bayeux, T.; Keirsbulck, M. Mould in indoor environments: The role of heating, ventilation and fuel poverty. A French perspective. Build. Environ. 2020, 169, 106577.

- Samson, R.A.; Houbraken, J.; Thrane, U.; Frisvad, J.C.; Andersen, B. Food and Indoor Fungi, 2nd ed.; CBS-KNAW Fungal Biodiversity Centre: Utrecht, The Netherlands, 2019.

- Andersen, B.; Frisvad, J.C.; Søndergaard, I.; Rasmussen, I.S.; Larsen, L.S. Associations between fungal species and water-damaged building materials. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 4180–4188.

- Mensah-Attipoe, J.; Toyinbo, O. Fungal growth and aerosolization from various conditions and materials. In Fungal Infection; de Loreto, É.S., Tondolo, J.S.M., Eds.; IntechOpen Limited: London, UK, 2019.

- Viitanen, H.A.; Vinha, J.; Salminen, K.; Ojanen, T.; Peuhkuri, R.; Paajanen, L.; Lähdesmäki, K. Moisture and bio-deterioration risk of building materials and structures. J. Build. Phys. 2010, 33, 201–224.

- Adan, O.C.G.; Samson, R.A. Fundamentals of Mold Growth in Indoor Environments and Strategies for Healthy Living; Wageningen Academic Publishers: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2011.

- Adan, O. On the Fungal Defacement of Interior Finishes. Ph.D. Thesis, Eindhoven University of Technology, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 1994.

- Mendell, M.J.; Macher, J.M.; Kumagai, K. Measured moisture in buildings and adverse health effects: A review. Indoor Air 2018, 28, 488–499.

- Pasanen, A.L.; Kalliokoski, P.; Pasanen, P.; Jantunen, M.J.; Nevalainen, A. Laboratory studies on the relationship between fungal growth and atmospheric temperature and humidity. Environ. Int. 1991, 17, 225–228.

- Ayerst, G. The effects of moisture and temperature on growth and spore germination in some fungi. J. Stored Prod. Res. 1969, 5, 127–141.

- Grant, C.; Hunter, C.A.; Flannigan, B.; Bravery, A.F. The moisture requirements of moulds isolated from domestic dwellings. Int. Biodeterior. 1989, 25, 259–284.

- Nielsen, K.F.; Gravesen, S.; Nielsen, P.A.; Andersen, B.; Thrane, U.; Frisvad, J.C. Production of mycotoxins on artificially and naturally infested building materials. Mycopathologia 1999, 145, 43–56.

- Kanekar, P.P.; Kanekar, S.P. Halophilic and Halotolerant Microorganisms. In Diversity and Biotechnology of Extremophilic Microorganisms from India. Microorganisms for Sustainability; Springer: Singapore, 2022; pp. 13–69.

- Nielsen, K.F. Mould Growth on Building Materials Secondary Metabolites, Mycotoxins and Biomarkers. Ph.D. Thesis, The Mycology Group, Technical University of Denmark, Lyngby, Denmark, 2001.

- Pasanen, A.L.; Rautiala, S.; Kasanen, J.P.; Raunio, P.; Ramtamäki, J.; Kalliokoski, P. The relationship between measured moisture conditions and fungal concentrations in water-damaged building materials. Indoor Air 2000, 10, 111–120.

- Pasanen, A.L.; Kasanen, J.P.; Rautiala, S.; Ikäheimo, M.; Rantammäki, J.; Kääriäinen, H.; Kalliokoski, P. Fungal growth and survival in building materials under fluctuating moisture and temperature conditions. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2000, 46, 117–127.

- Ponizovskaya, V.B.; Rebrikova, N.L.; Kachalkin, A.V.; Antropova, A.B.; Bilanenko, E.N.; Mokeeva, V.L. Micromycetes as colonizers of mineral building materials in historic monuments and museums. Fungal Biol. 2019, 123, 290–306.

- Thrane, U.; Olsen, K.C.; Brandt, E.; Ebbehøj, N.E.; Gunnarsen, L. SBi-Anvisning 274: Skimmelsvampe i Bygninger-Undersøgelse af Vurdering/SBi Guidelines 274: Fungal Growth in Buildings-Investigation and Assessment; BUILD, Aalborg Universitet: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2020.

- Pitt, J.I.; Hocking, A.D. Fungi and Food Spoilage, 3rd ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2009.

- Frazer, S.; Magan, N.; Aldred, D. The influence of water activity and temperature on germination, growth and sporulation of Stachybotrys chartarum strains. Mycopathologia 2011, 172, 17–23.

- Ponizovskaya, V.B.; Antropova, A.B.; Mokeeva, V.L.; Bilanenko, E.N.; Chekunova, L.N. Effect of Water Activity and Relative Humidity on the Growth of Penicillium chrysogenum Thom, Aspergillus repens (Corda) Sacc., and Trichoderma viride Pers. Isolated from Living Spaces. Microbiology 2011, 80, 378–385.

- Segers, F.J.J.; Meijer, M.; Houbraken, J.; Samson, R.A.; Wösten, H.A.B.; Dijksterhuis, J. Xerotolerant Cladosporium sphaerospermum are predominant on indoor surfaces compared to other Cladosporium species. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0145415.

- Bastholm, C.J.; Madsen, A.M.; Andersen, B.; Frisvad, J.C.; Richter, J. The mysterious mould outbreak—A comprehensive fungal colonisation in a climate-controlled museum repository challenges the environmental guidelines for heritage collections. J. Cult. Herit. 2022, 55, 78–87.

- Smith, S.L.; Hill, S. Influence of temperature and water activity on germination and growth of Aspergillus restrictus and A. versicolor. Trans. Br. Mycol. Soc. 1982, 79, 558–560.

- Hocking, A.D.; Pitt, J.I. Two new species of xerophilic fungi and a further record of Eurotium halophilicum. Mycologia 1988, 80, 82–88.

- Stevenson, A.; Hamill, P.G.; O’Kane, C.J.; Kminek, G.; Rummel, J.D.; Voytek, M.A.; Dijksterhuis, J.; Hallsworth, J.E. Aspergillus penicillioides differentiation and cell division at 0.585 water activity. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 19, 687–697.

- Sklenář, F.; Jurjević, Ž.; Zalar, P.; Frisvad, J.; Visagie, C.; Kolařík, M.; Houbraken, J.; Chen, A.; Yilmaz, N.; Seifert, K.; et al. Phylogeny of xerophilic aspergilli (subgenus Aspergillus) and taxonomic revision of section Restricti. Stud. Mycol. 2017, 88, 161–236.

- Laks, P.E.; Richter, D.L.; Larkin, G.M. Fungal susceptibility of interior commercial building panels. For. Prod. J. 2002, 52, 41–44.

- Vanpachtenbeke, M.; Bulcke, J.V.D.; Acker, J.V.; Roels, S. Performance of wood and wood-based materials regarding fungal decay. E3S Web Conf. 2020, 172, 20010.

- Johansson, P.; Ekstrand-Tobin, A.; Svensson, T.; Bok, G. Laboratory study to determine the critical moisture level for mould growth on building materials. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2012, 73, 23–32.

- Hoang, C.P.; Kinney, K.A.; Corsi, R.L.; Szaniszlo, P.J. Resistance of green building materials to fungal growth. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2010, 64, 104–113.

- Singh, J. Dry rot and other wood-destroying fungi: Their occurrence, biology, pathology and control. Indoor Built Environ. 1999, 8, 3–20.

- Piecková, E.; Pivovarová, Z.; Sternová, Z.; Droba, E. Building materials vs. fungal colonization-Model experiments. In Environmental Health Risk IV; Brebbia, C., Ed.; WIT Transactions on Biomedicine and Health, WIT Press, Ashurst Lodge, Ashurst: Southampton, UK, 2007; Volume 11, pp. 71–78.

- Valette, N.; Perrot, T.; Sormani, R.; Gelhaye, E.; Morel-Rouhier, M. Antifungal activities of wood extractives. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2017, 31, 113–123.

- Méheust, D.; Cann, P.L.; Reboux, G.; Millon, L.; Gangneux, J.P. Indoor fungal contamination: Health risks and measurement methods in hospitals, homes and workplaces. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2014, 40, 248–260.

- Polizzi, V.; Delmulle, B.; Adams, A.; Moretti, A.; Susca, A.; Picco, A.M.; Rosseel, Y.; Kindt, R.; Bocxlaer, J.V.; Kimpe, N.D.; et al. JEM Spotlight: Fungi, mycotoxins and microbial volatile organic compounds in mouldy interiors from water-damaged buildings. J. Environ. Monit. 2009, 11, 1849–1858.

- Jagels, A.; Stephan, F.; Ernst, S.; Lindemann, V.; Cramer, B.; Hübner, F.; Humpf, H.U. Artificial vs natural Stachybotrys infestation—Comparison of mycotoxin production on various building materials. Indoor Air 2020, 30, 1268–1282.

- Tuomi, T.; Reijula, K.; Johnsson, T.; Hemminki, K.; Hintikka, E.L.; Lindroos, O.; Kalso, S.; Koukila-Kähkölä, P.; Mussalo-Rauhamaa, H.; Haahtela, T. Mycotoxins in crude building materials from water-damaged buildings. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 1899–1904.

- Aktas, Y.D.; Ioannou, I.; Altamirano, H.; Reeslev, M.; D’Ayala, D.; May, N.; Canales, M. Surface and passive/active air mould sampling: A testing exercise in a North London housing estate. Sc. Total Environ. 2018, 643, 1631–1643.

- Adams, R.I.; Sylvain, I.; Spilak, M.P.; Taylor, J.W.; Waring, M.S.; Mendell, M.J. Fungal signature of moisture damage in buildings: Identification by targeted and untargeted approaches with mycobiome data. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 86, e01047-20.

- Vesper, S. Traditional mould analysis compared to a DNA-based method of mould analysis. Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 2011, 37, 15–24.

- Portnoy, J.M.; Barnes, C.S.; Kennedy, K. Sampling for indoor fungi. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2004, 113, 189–198.

- Ding, X.; Lan, W.; Gu, J.D. A review on sampling techniques and analytical methods for microbiota of cultural properties and historical architecture. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 8099.

- Aktas, Y.D.; Altamirano, H.; Ioannou, I.; May, N.; D’Ayala, D. Indoor Mould Testing and Benchmarking: A Public Report; UK Centre for Moisture in Buildings (UKCMB): Leicestershire, UK, 2018.

- Frankel, M.; Timm, M.; Hansen, E.W.; Madsen, A.M. Comparison of sampling methods for the assessment of indoor microbial exposure. Indoor Air 2012, 22, 405–414.

- Würtz, H.; Sigsgaard, T.; Valbjørn, O.; Doekes, G.; Meyer, H.W. The dustfall collector-A simple passive tool for long-term collection of airborne dust: A project under the Danish Mould in Buildings program (DAMIB). Indoor Air 2005, 15, 33–40.

- Noss, I.; Wouters, I.M.; Visser, M.; Heederik, D.J.J.; Thorne, P.S.; Brunekreef, B.; Doekes, G. Evaluation of a low-cost Electrostatic Dust Fall Collector for indoor air endotoxin exposure assessment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2008, 74, 5621–5627.

- Ruiz-Jimenez, J.; Heiskanen, I.; Tanskanen, V.; Hartonen, K.; Riekkola, M.L. Analysis of indoor air emissions: From building materials to biogenic and anthropogenic activities. J. Chromatogr. Open 2022, 2, 100041.

- Hyvärinen, A.; Roponen, M.; Tiittanen, P.; Laitinen, S.; Nevalainen, A.; Pekkanen, J. Dust sampling methods for endotoxin—An essential, but underestimated issue. Indoor Air 2006, 16, 20–27.

- Andersen, B. Anvendelse af Støv fra støVsugerposer-Som mål til Vurdering af Skimmelsvampevækst i Boliger/Use of Dust from Vacuum Cleaner Bags as a Measure for Assessing Fungal Growth in Homes; BUILD Rapport Nr. 2022:12; Institut for Byggeri, By og Miljø (BUILD), Aalborg Universitet: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2022.

- Pasanen, A.L. A Review: Fungal Exposure Assessment in Indoor Environments. Indoor Air 2001, 11, 87–98.

- Bellanger, A.P.; Reboux, G.; Scherer, E.; Vacheyrou, M.; Millon, L. Contribution of a Cyclonic-Based Liquid Air Collector for Detecting Aspergillus Fumigatus by QPCR in Air Samples. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2012, 9, D7–D11.

- Cox, J.; Mbareche, H.; Lindsley, W.G.; Duchaine, C. Field sampling of indoor bioaerosols. Aerosol Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 572–584.

- Mbareche, H.; Brisebois, E.; Veillette, M.; Duchaine, C. Bioaerosol sampling and detection methods based on molecular approaches: No pain no gain. Sc. Total Environ. 2017, 599–600, 2095–2104.

- Unterwurzacher, V.; Pogner, C.; Berger, H.; Strauss, J.; Strauss-Goller, S.; Gorfer, M. Validation of a quantitative PCR based detection system for indoor mold exposure assessment in bioaerosols. Environ. Sci. Processes. Impacts. 2018, 20, 1454–1468.

- Švajlenka, J.; Kozlovská, M.; Pošiváková, T. Assessment and biomonitoring indoor environment of buildings. Int. J. Environ. Health Res. 2017, 27, 427–439.

- Pietarinen, V.M.; Rintala, H.; Hyvärinen, A.; Lignell, U.; Kärkkäinen, P.; Nevalainen, A. Quantitative PCR analysis of fungi and bacteria in building materials and comparison to culture-based analysis. J. Environ. Monit. 2008, 10, 655–663.

- Advantages of Next-Generation Sequencing vs. qPCR. Available online: https://emea.illumina.com/science/technology/next-generation-sequencing/ngs-vs-qpcr (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Niemeier, R.T.; Sivasubramani, S.K.; Reponen, T.; Grinshpun, S.A. Assessment of fungal contamination in moldy homes: Comparison of different methods. J. Occup. Environ. Hyg. 2006, 3, 262–273.

- Reeslev, M.; Miller, M.; Nielsen, K.F. Quantifying mold biomass on gypsum board: Comparison of ergosterol and beta-N-acetylhexosaminidase as mold biomass parameters. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 3996–3998.

- Efthymiopoulos, S.; Aktas, Y.D.; Altamirano, H. Mind the gap between non-activated (non-aggressive) and activated (aggressive) indoor fungal testing: Impact of pre-sampling environmental settings on indoor air readings. UCL Open Environ. 2023, 5, e055.

- Park, J.H.; Sulyok, M.; Lemons, A.R.; Green, B.J.; Cox-Ganser, J.M. Characterization of fungi in office dust: Comparing results of microbial secondary metabolites, fungal internal transcribed spacer region sequencing, viable culture and other microbial indices. Indoor Air 2018, 28, 708–720.

- Andersson, M.A.; Nikulin, M.; Köljalg, U.; Andersson, M.C.; Rainey, F.; Reijula, K.; Hintikka, E.L.; Salkinoja-Salonen, M. Bacteria, molds, and toxins in water-damaged building materials. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1997, 63, 387–393.

- Trovão, J.; Portugal, A.; Soares, F.; Paiva, D.S.; Mesquita, N.; Coelho, C.; Pinheiro, A.C.; Catarino, L.; Gil, F.; Tiago, I. Fungal diversity and distribution across distinct biodeterioration phenomena in limestone walls of the old cathedral of Coimbra, UNESCO World Heritage Site. Int. Biodeterior. Biodegrad. 2019, 142, 91–102.

More

Information

Subjects:

Construction & Building Technology; Mycology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.5K

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

29 Feb 2024

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No