Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Adekunle Mofolasayo | -- | 8239 | 2024-02-02 06:31:00 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | Meta information modification | 8239 | 2024-02-02 07:52:08 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Mofolasayo, A. Human Factors and Road Traffic Safety. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/54664 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Mofolasayo A. Human Factors and Road Traffic Safety. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/54664. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Mofolasayo, Adekunle. "Human Factors and Road Traffic Safety" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/54664 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Mofolasayo, A. (2024, February 02). Human Factors and Road Traffic Safety. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/54664

Mofolasayo, Adekunle. "Human Factors and Road Traffic Safety." Encyclopedia. Web. 02 February, 2024.

Copy Citation

Human factors play a huge role in road traffic safety. Research has found that a huge proportion of traffic crashes occur due to some form of human error. Improving road user behavior has been the major strategy that has been emphasized for improving road traffic safety. Meanwhile, despite the training efforts, and testing for drivers, the global status of road traffic safety is alarming.

human factors

road traffic safety

vehicle standards

automation

1. Introduction

Human factors play a huge role in road traffic safety. Previous works have reported that more than 90% of road traffic crashes occur because of some form of human error [1][2][3]. Although significant progress in traffic safety has been achieved, the results are still not satisfying [1]. Vehicle collisions have been a significant concern for researchers, governments, and automobile manufacturers over the past two decades [4]. Globally, fatalities due to road crashes are rising [5]. Despite the recent development in tackling the challenges of road safety, especially in developed countries, road traffic crashes account for 1.35 million deaths annually and cost over $65 US billion [6]. Among other things, some researchers [7] noted that the criticality of a road depends on the road condition and human factors. Actually, the major ‘interacting factors’ are the road, the vehicle, the environment, humans in and outside of the vehicle, traffic control devices, other road infrastructures, and various objects in and outside of the vehicle that can contribute to distraction for the driver. The ability to perceive and adequately react to an urgent issue during the driving task is dependent on a range of factors. Perception and reaction times increase with factors such as fatigue, the presence of drugs, and/or alcohol in the driver’s system, age, and the complexity of the reaction [8]. Meanwhile, a driver that is distracted would have traveled some distance before realizing an issue that needs attention on the road. A driver that is fatigued may fall asleep behind the wheel. Human factors in driving can also be related to the level of experience of the driver. The age of drivers and driving history show a significant impact on some driving behavior indices and reaction time [9]. When the difficulty of driving increases, experienced drivers spend more time scanning and less time looking at their surroundings, while novice drivers do the opposite. In addition, some novice drivers cannot reasonably combine both steering and braking for emergency driving like experience drivers [10].

The expected benefits of automated driving include a reduction in traffic accidents and an increase in drive safety and comfort [11]. The European Commission, ref. [12] reported that CAVs are emerging as a new form of mobility and new technology that can help bring down Europe’s number of road fatalities to near zero, help reduce traffic emissions and increase the accessibility of mobility services. The availability of automation technologies for automobiles and other road vehicles is increasing, and further advances are expected in the coming years [13]. More and more cars in the cities today are equipped with autonomous driving systems that are aimed at improving road safety and reducing accidents, to halve accident fatalities as quickly as possible [14]. France published a decree that adapts the provisions of the highway code and transport code to allow for automated driving systems and vehicles that are equipped with delegated driving systems on predefined routes (from September 2022). Similar legislation includes the announcement by the UK government to allow hands-free automated vehicles that offers automated lane-keeping systems on UK roads, while Germany is adopting legislation that will allow driverless delivery services and Robotaxis on public roads by 2022 [15]. Automated commercial motor vehicles have the potential to reduce crashes, significantly reduce the stress of driving, and enhance traffic flow [9]. Although a huge number of challenges must be solved by vehicle manufacturers before the widespread use of autonomous vehicles (AVs) can be achieved, AVs have significant potential to increase road safety in both freight and passenger transport [16]. Expected benefits of vehicles that operate independently of real-time human control include an increase in the capacity of the road network and freeing up of the driver-occupant’s time to engage in leisure or non-driving economically-productive tasks of their choice [17].

Advanced driver assistance system ADAS (which is one of the major objectives of the intelligent transportation system, ITS) technology plays an important role in ensuring driver, vehicle, pedestrian, and passenger safety and comfort [18]. In different parts of the world, the intelligent transportation system (ITS) is gaining acceptance. In many technologically advanced countries, the connected vehicle component of ITS is considered a high research priority as it is expected that connected vehicles will be efficient, safe, and eco-friendly in their operations [19]. To improve safety and performance in driving an automobile, advanced driver support systems such as lane keeping and pre-crash systems have been actively researched [20]. In critical situations, driver assistance systems improve safety by supporting the driver. Safety features like emergency braking assist, automatic emergency braking, and predictive collision warning rely on an accurate measurement of the relative velocity and distance to the preceding vehicle. Side view assist alerts drivers of vehicles that are hidden in the blind spot in critical situations. Optimal collision warnings can help a driver avoid a rear-end collision [1]. Autonomous vehicles face a number of challenges that limits their operation and widespread acceptance. These challenges include cybersecurity, traffic management strategies, moral and ethical challenges, legal terms, and operational challenges. The operational challenges can be further broken down into challenges with environmental perception, vehicle control, path planning, and self-localization. The challenges with environmental perception can be broken down into algorithm challenges (hardware limitations, availability of datasets and training data, computational time and complexity) and operational design domain, ODD (variable weather and lightning conditions, small/distant objects, movement of objects, the reflectivity of objects, obstacles occlusion and truncation, etc. [21]. In order to achieve the vision of widespread use of highly automated driving, the safety of automated vehicles must be guaranteed through extensive testing of the safety systems of the vehicle [22]. In addition, it is necessary for the human driver to safely take over the driving operation when a breakdown occurs or when the system reaches its functional limit [23]. The interest in autonomous driving is not new. To reduce accidents, it is necessary to automate the driving operation [24].

2. Human Factors and Road Traffic Safety

2.1. Driver Fatigue

Driver fatigue has been found to be one of the major factors that negatively impact road traffic safety. Driver fatigue, sleep restriction, and falling asleep while at the wheel has been identified as some of the major factors that contribute to accidents on the road [25]. Various researchers have presented figures that indicated that driver fatigue is a significant contributor to traffic crashes. Some researchers [26] identified driver fatigue as a critical aspect of public health that is responsible for 10–40% of road crashes. The European Transport Safety Council report [27] on the role of driver fatigue in commercial road transport crashes also noted that driver fatigue has been identified as a significant factor that contributes to about 20% of road crashes, with surveys showing that over 50% of long-haul drivers have fallen asleep at some point behind the wheels. Interacting factors that contribute to fatigue have been identified as the time that is available for rest and continuous sleep, length of continuous work and daily duty, and the arrangement of duty with rest and sleep within every 24 h cycle [28]. The Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents [29] indicated that there will be impairment of performance if sleeping is less than 4 h per night. Alertness, concentration, vigilance, and reaction time (critical elements for safe driving) are reduced by sleepiness. The causes of accidents as noted by some other researchers [30] include: sleep disorders, hours of work driving, alcohol and drug abuse, higher levels of sleepiness, higher levels of stress, fatigue, lapses of attention, OSAS associated with alcohol, higher body mass index (BMI), and sleep medication.

It is generally recognized that fatigue does not only result from prolonged activities. Socioeconomic, psychological, and other environmental factors that affect the body and the mind also cause fatigue [28]. While the contributing factors to fatigue as stated [28] are valid, there may be the need for more research into how other factors that could cause undesirable stress for various people lead to various forms of fatigue, absent-mindedness, and eventually accidents on the road. Although some recommendation that should minimize the impact of driver fatigue has been made in the literature, driver fatigue remains a challenge on the roads. The strategies to prevent crashes include naps, caffeine intake, physical exercise, breaks to rest, healthy nutritional habits, restorative sleep, phototherapy, reducing working hours at the wheel, and treatment of sleep disorders [30].

Some behavioral psychometric and physiological tests that are being used increasingly to evaluate the impact of fatigue on driver performance include polysomnography, actigraphy, oculography, and the maintenance of wakefulness test, etc. [30]. In evaluating the issue of fatigue, sleepiness behind the wheels, and the need for a reasonable degree of automation to help human drivers avoid traffic crashes, some important questions to ask include:

-

Is it possible for humans to completely eradicate various stressors that may result in driver fatigue?

-

Could there be some undiagnosed medical conditions or emotional issues that could result in more likelihood of sleepiness behind the wheel for various people?

-

Will it not be an invasion of people’s privacy if anyone tries to monitor or confirm the amount of sleep that a driver has had before getting behind the wheel?

-

Is there a universal agreement on the amount of rest that everyone needs, to avoid fatigue or sleepiness behind the wheel and can this be effective for everyone?

-

Is it possible to enforce a universal plan (that everyone will truly follow) for work and rest before driving a motor vehicle?

Some researchers [30] in the study about “sleep disorders as a cause of motor vehicle collisions” cited studies that indicated that sleep disorders like insomnia, narcolepsy, obstructive sleep apnea (OSA), etc. are associated with excessive sleepiness, cognitive deficits, and fatigue symptoms like reduced driving skills, and these have been linked to increased risks of highway accidents and fatalities. The study also recommended that all disorders that produce excessive sleepiness should be investigated and monitored to reduce accidents, associated injuries, and loss of lives on the highway. Even if a driver is well rested, it is also not going to be an easy task for law enforcement officers to know at what point a driver needs a break from driving in order to avoid falling asleep.

2.2. Distracted Driving

Distracted driving is a serious issue in road traffic safety. The Center for Disease and Control Prevention, as well as NHTSA, have classified distracted driving into three main categories. These include: visual, a situation in which the eyes are taken off the road, manual, a situation in which the hands are taken off the wheels, and cognitive, a situation in which the minds are taken off driving. While cognitive distraction is a state of diminished vigilance with respect to the driving environment, visual distraction occurs when the attention of the driver is diverted from the direction of travel of the vehicle [31]. Some researchers [32] classified three types of distraction into physical tasks, auditory or visual diversions, and cognitive activities, and further noted that some forms of activities like texting can include three types of distraction (physical, visual and cognitive), given that eyes, minds, and hands can be engaged in the distracting operation. Various efforts have been made in research to evaluate how the distraction of drivers can be evaluated. Gaze angle, eye closure, and blink are usually used to evaluate the variations in the driver’s cognitive states [33]. The human pupil is also considered an indicator of cognitive load. Previous studies have suggested that variation in the size of the pupil is related to cognitive information processing [33]. As opposed to the standard deviations of gaze angle and head rotation angle, some researchers [31] were able to improve the performance for detection of driver’s cognitive distraction by adding the average value of heart rate RRI (interval between R-waves) from the electrocardiogram (ECG) waveforms and the average value of the diameter of the pupil from camera images.

Distraction can occur when drivers have to take their eyes off the road to look at the information on the display boards in the vehicles (Head-down display, HDD). Another study [34] looked into the potential impacts of both head-up-display (HUD) and head-down-display (HDD). There is no agreement in the research effort on whether head-up displays cause less distraction to drivers than head-down displays. The use of smartphones while driving comes with great risk in the task of guiding the vehicle safely [35]. The potential risk to road safety due to the exponential growth in mobile phone use in society has become a matter of concern for policymakers. The proportion of drivers using mobile phones while driving has also increased. Although it may not be an easy task to ascertain the exact impact of the use of mobile phones on crashes, some studies have indicated that drivers who use a cell phone while driving are four times more likely to be involved in a crash [36].

2.2.1. Evaluation of Distance Traveled While Being Distracted

The distance that a vehicle would have traveled within a specified time while being distracted is dependent on the speed at which the vehicle is moving. It is known that the distance covered by a moving object can be represented by a product of speed and time. The higher the speed, the higher the distance that is traveled within a specified time. If the driver is distracted at the same time, there is a high chance of severe collision if an object is on the way. The result presented above shows that in addition to distraction, speed also contributes to fatal collisions in Canada. The Center for Disease and Control (CDC) noted that at 55 mph, a driver that is texting or reading a text, whose eyes are off the road for about 5 s would have traveled a distance that is long enough to cover a football field [37]. Within the period of distraction, traffic crashes that may result in property damage, injury, and even fatality could have occurred.

2.2.2. Expectations of a Good Auto-Pilot System While a Driver Is Distracted

In using automation to assist human driving, it is important to ensure that the driver knows the limit for the auto-pilot. For example:

-

A good automation system should be one that can audibly communicate its limitations in real life.

-

When entering new routes or areas that the automation is not familiar with, the driver should be alerted by the automation system.

-

If road conditions are bad, or when the friction between the tires and the road is such that the estimated time to reach a stopping point may not be achievable, the automation system should be able to alert the driver.

-

If using cameras for the lane departure warning system, and the lane markings are not visible to the auto-assist system (e.g., when the road is covered with snow, or when lane markers are not yet on the road), the automation system should be able to alert the driver, both audibly, on a screen in the vehicle, and possibly through vibration.

-

When the driver decides to take full control of the driving and the driver gets too close to another vehicle either through distraction, sleepiness, etc., a good auto-assist system should be able to alert the driver audibly, through a screen display, a vibration (on the seat, steering or the entire vehicle), and other means that may put the driver back on an alert mode.

-

If the driver is unresponsive to the impending collision, a good auto-assist system should be able to initiate braking operations to avoid or reduce the severity of the traffic crash.

Road traffic safety measures need to consider how the vehicle, human, and environmental risks intersect to influence the likelihood and severity of injury [38].

2.2.3. Perception-Reaction Time (PRT) and Total Stopping Distance

During a driving task, the foot is not applied on the brake immediately when the eye perceives an issue that warrants a reaction. The American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials (AASHTO) [39] noted that 2.5 s is considered adequate as a brake-reaction time, as it exceeds the 90th percentile of reaction time for drivers. However, it was also noted that while some drivers have less reaction time, most complex conditions during driving tasks require a higher reaction time. Various other braking reaction times exist for different situations. In simple braking operations, the perception reaction time (PRT) is said to begin when the driver first perceives an event that warrants a braking action and terminates when the foot is applied to the brake [8]. The equation for the calculation of the expected total stopping distance was presented in previous work [8]. The human factor here is dependent on how quickly the human driver can react to a hazard on the road at a given speed under the prevailing road and weather conditions.

2.2.4. The Challenge in Bringing the Vehicle to a Stop after Perception of a Hazardous Event

Apart from the fact that distraction increases the distance traveled before a driver becomes aware of an issue that warrants braking operations, to reduce the total stopping distance after the driver becomes aware of the issue that needs attention, the major factors that determine the total stopping distance include:

-

The perception reaction time,

-

The speed of the vehicle, and

-

The deceleration rates [39]

It may also take a distracted driver a long time to perceive a potential hazard that warrants a reaction. In addition to the speed of the vehicle, the effect of grade and acceleration due to gravity also plays a role in the braking distance [8].

2.2.5. Recommendations to Reduce the Total Stopping Distance from PRT Analysis of Braking Operations

Knowing that the concept of total stopping distance is crucial in road traffic safety (especially, given its impact when a driver is distracted) and that it is highly desirable to bring a vehicle to a stop before a collision with an object, the following recommendations are made:

-

Ensure maintenance and enforcement of appropriate speed limit (giving consideration for the grade of the road, weather conditions, and friction forces between the tires and the road surface)

-

Promote research in technologies that can greatly increase the deceleration rate at operating speeds of vehicles

-

Incorporate autonomous systems that can automatically detect and react to an issue that needs an action during the driving task.

2.2.6. Effects of Outside Objects on Driver Performance

Distraction from an outside object is also a huge factor that negatively impacts road traffic safety. In a review of the impact that billboards have on drivers’ visual behavior, a previous work [40] noted that external distractions seem to account for at least 6–9% of motor vehicle collisions in which distraction was a factor. The study also noted that considerable evidence exists to show that about 10–20% of all glances at billboards were ≥0.75 s. In a study about the effect of roadside advertisements on driver distraction, researchers [41] noted that conservative estimates put external distractors as responsible for up to 10% of all accidents, and although roadside advertisements are designed to attract attention, the industry does not acknowledge their potential threat to road safety.

2.3. Driving under the Influence of Drugs and Alcohol

Driving under the influence of drugs and or alcohol is another dangerous human factor in road traffic safety. In a study aimed at assessing the risk of having a traffic accident after using single drugs, alcohol, or a combination, and determining concentrations in which the risks significantly increased, some researchers [42] (in addition to other findings) noted that alcohol, in general, caused an increased risk of a crash. Cannabis (in general) also resulted in an increased risk of accidents. At a concentration of 2 ng/mL of THC, accident risk was found to be four times the risk of the lowest concentration of THC. A report [43] identified THC as “tetrahydrocannabinol”, a chemical that is responsible for most of the psychological effects of Marijuana. The National Institute of Drug Abuse [44] referred to THC as a mind-altering chemical delta-9-tetrahydrocannabinol that is contained in Marijuana (Cannabis Sativa). THC is said to have the capability to change thinking, induce hallucinations, and cause delusions [43]. Cannabis has been identified as the second most impairing drug that is used in the world, after alcohol. The risk of being involved in a crash is said to be doubled when the blood alcohol level is between 0.05 and 0.08%, and at a blood alcohol level of 0.24%, the risk of a crash increases to more than 150-fold [45]. Road transportation safety will surely be in greater trouble if more people drive on the road with a significant amount of THC or alcohol, which can affect their normal thinking process, perception, and reaction time. While cannabis and alcohol cause acute impairment of many driving-related skills in a dose-related way, the effect of cannabis varies more between people than they do with alcohol, because of differences in smoking techniques, tolerance, and absorptions of THC [46].

Drunk road users in cars and pickups have the greatest odds of being a victim of a fatal crash [47]. The above results indicate that driving ‘under the influence’ is one of the factors that has contributed to fatal collisions in Canada. Drunk drivers are not only a threat to their own safety, they are threats to the safety of other road users. With this knowledge, it is important that enforcement actions be increased to reduce the chance of drunk driving. Random police inspection can be increased, especially during the time that is common that there will be drunk drivers outside. Those who sell alcohol may be obliged to take the car keys away from their customer and call a taxi if the customer is drunk, or even call the police if one of their drunk customers gets behind the wheel. Fines may be issued to liquor sellers if it is known that a drunk person was allowed to drive away from their center without attempting to restrain the drunk person. Police checkpoints for drunk driving may be situated close to liquor stations. These random checks may be increased to discourage drunk drivers. Adequate fines for drunk driving, including revocation of driving license after an agreed limit for a repetition of the drunk driving offence may be considered in places that do not enforce such fines.

2.4. Major Emphasis on Road Safety Approach and the Proposed Way Forward

Improving road user behavior has been the major strategy that has been emphasized for road traffic safety [48]. While efforts to improve road user behavior may include things like driver training, and re-training, public education, enforcement of traffic laws, etc., with the number of traffic fatalities that still occur on the roads in various jurisdictions, does this mean that people do not have adequate driving training before they obtain a driving license? Are the driving licensing officers not doing adequate jobs? As T in this study, there is no doubt that humans have some serious limitations that contribute to traffic crashes. If it is known that relying on the hope of improving road user behavior alone has not improved road traffic safety to the desirable extent worldwide, certainly, it is time to expand the major strategy beyond the realm of hoping to improve road user behavior. It will be desirable to see the implementation of minimum vehicle standards that has various levels of automation to help ensure that human errors do not result in negative consequences for various road users. At a minimum, vehicle standards should be increased to ensure that all vehicles on the road have auto-brake systems to prevent both frontal and backward collisions [49]. Such auto-brake systems should be capable of detecting objects in the trajectory of the moving vehicles and efficiently reduce speed to prevent a collision. Such collision avoidance systems will go a long way to reduce road traffic crashes and their associated consequences globally. If properly enforced, such a collision avoidance system should also help deter/prevent the use of automobiles as weapons of mass destruction for unsuspecting vulnerable road users. If well implemented, connected vehicle technology in combination with auto-braking systems for trucks, busses, and other vehicles for mass transit (as a supplement to human driving efforts) is also expected to help reduce the possibility of collisions at intersections.

While addressing a question about if autonomous vehicles will completely replace human drivers, as raised in the Federal Automated Vehicle Policy [50], a researcher [49] suggested that pilot projects be conducted in various communities to validate the efficiency of autonomous systems. If there are no accidents at all while autonomous vehicles are on the road, this may form the basis for the adoption of fully autonomous vehicles on a large scale. It is no doubt that all traffic crashes require a thorough investigation to determine the cause, and create lessons learned for future improvement. Continuous, and rigorous investigations of any traffic crash involving vehicles with autonomous systems are recommended to ensure that the cause of any system failure is identified, and information about the necessary improvement of the technology is openly shared with all automobile manufacturers. It will be a good idea to ensure that all automobiles have not only a system that can report the present fault in the vehicles, but also a system that can track the repairs, and maintenance that has been conducted on the vehicles.

At this time, it is known that not everyone appears to be comfortable with full autonomy for roadway vehicles. A study [51] that evaluates if consumers are willing to pay to let cars drive for them noted that a semiparametric random parameter logit estimate indicates that there is an approximately even split between, no demand, modest, and high demand for automation. In a study about public opinion on automated driving, some researchers [52] also found that public opinion about autonomous driving is diverse. 69% of people believe that automated driving will reach 50% market share by 2050. While some people welcome the idea of fully automated driving, another large portion of people is of the opinion that autonomous driving will not provide an enjoyable experience and are not willing to pay for it. The study also noted that the main concerns that were raised about autonomous driving include software hacking/misuse, data transmitting issues, legal, and safety.

2.5. What Is a Reasonable Degree of Automation for Roadway Motor Vehicles?

The above question is one that is expected to evolve from one generation to another. It may also be affected by the advancements in technological innovations in the transportation industry. Firstly, it is good to know that it will not be a wise idea to have a technology that can save lives, and not put it to good use. In this age, humanity at large has grown to see innovative technologies that can help humans better monitor the driving environment (or at least complement human efforts), and also take necessary actions to bring the vehicle to a stop to avoid a traffic crash. If these technologies can help save lives, and drastically reduce traffic fatalities on the roads globally, why should anyone be against it? One of the issues that have been raised in previous research is about the ‘enjoyable experience’ in driving operations [52]. If what is presently considered an enjoyable experience in driving operations contributes greatly to 1.25 million fatalities on the road (globally) every year, then humanity at large needs to answer the important question, “is this so-called ‘enjoyable experience’ a reasonable one, considering the number of traffic fatalities”? It is very obvious that humans have great limitations that previous road traffic safety efforts have not been able to overcome.

Even though there is a lot of optimism about the expected safety benefits of autonomous driving, it does not come without its challenges. In order to derive requirements for safe and effective remote assistance and remote driving of autonomous vehicles and also create suitable human-centered solutions for human-machine interfaces, the researchers [53] compiled a set of 74 core scenarios that are likely to occur in public transport while using automated vehicles. Some of the lists of scenarios in remote operation include the cases in which there are:

-

Vandalism (in which there is damage to the autonomous vehicle inside or outside. In this case, AV cannot continue the ride).

-

Passenger abuse of the intercom (that can result in distraction of the controller center employee).

-

Partial defect in the autonomous vehicle, but it is still operatable (in this case, the autonomous vehicle stops).

-

Difficult weather conditions (in which there is overload or soiling of the sensors on the vehicle. In this case, the autonomous vehicle cannot continue its journey), etc.

Rather than trying to navigate through unfamiliar territory, it is reasonable that some autonomous vehicles require that human drivers take over the driving operations when the autonomous systems encounter situations that are beyond their capability. A study [54] noted that a take-over request is issued to transfer the driving operations to the driver (from the system) when the system is unable to continue the driving operations. In this case, a smooth take-over of the driving operation is essential to reduce the chance of traffic crashes. If the driver is asleep, or distracted and unable to respond on time to the take-over request, there is a likelihood of a traffic crash. For situations in which the driver failed to respond to a take-over request in an autonomous driving operation, it is important that such autonomous technology be equipped with systems that will gradually bring the vehicle to a stop while activating the hazard light.

2.6. Addressing the Ethics of Remote Driving and Automatic Braking Systems for Vehicles on the Road

As regards to autonomous driving, researchers [55] noted that there will certainly be problems (that are beyond the programming of autonomous vehicles) that will necessitate human involvement to assess the situation, make necessary corrections or direct the automation process. The summary of the responsibilities of the human driver and system at each level of automation is given by SAE international [56]. Level 0 is no automation, level 1 has driver assistance features, level 2 has partial automation, level 3 has conditional automation, level 4 has high automation, and level 5 is full automation [55][56]. In some cases, autonomous vehicles can be remotely operated. Meanwhile, situational awareness is different when drivers are in the vehicle that they are driving and when they are not there [55]. The detection of objects by autonomous vehicles is an important operation that comes before other tasks such as object tracking, trajectory estimation, and collision avoidance. Other tasks include path planning, ego-vehicle self-localization, environmental perception, and vehicle control. Due to continuous changes in behavior and location, dynamic variables on the road (vehicles, cyclists, and pedestrians) pose a greater challenge [21].

Remote driving comes with the ethical challenge of whether a remote driver should have the capability to override the auto-brake function of an autonomous vehicle. A previous study [57] noted that manual driving must override automated driving when a driver needs to avoid emergencies. The ethical question is the limit to what manual driving should be able to do (Should the ability to collide with an object be removed from manual driving, if it is not a law enforcement vehicle?). To ensure that autonomous vehicles are not being used for terrorist missions, hitting different targets in town without any driver behind the wheels, it is ideal to ensure that all autonomous vehicles have auto-brake functions that remote drivers cannot override (to ensure that the vehicle comes to a full stop upon detection of an obstacle, object, or person). To minimize the potential for head-on collisions, rear-end collisions, etc., the world still struggles with a decision on whether to make the auto-braking function mandatory for all vehicles on the road.

2.7. Removing Barriers to Improving Road Traffic Safety

It is no doubt that since no one can confidently say that humanity has a system that can make people concentrate on the driving task at all times, there is certainly a need for some autonomous system that can ensure that human errors do not result in dangerous consequences. Note that even if systems are implemented that warn drivers about impending danger, there is still a need for the driver to be in a reasonable state of mind to be able to properly respond to such an alert. Will such an alert be efficient for fatigued drivers or for someone who is driving under the influence of drugs or alcohol? Will such alerts stop a terrorist? If everyone has agreed that humans need autonomous systems like automatic braking systems, and other automatic crash prevention systems, the next question to address will be “what are the limiting factors that may create resistance to implementing technologies that are aimed at improving safety for everyone on the roads globally, and how can this be resolved”? Some of the crash avoidance features listed by the Insurance Institute for Highway Safety (IIHS) and the Highway Loss Data Institute (HLDI) mentioned earlier include auto-brake, adaptive headlights, and blind spot detection, lane departure prevention, forward collision warning, etc.

It is not a happy thing to see a traffic crash in which some fellow human beings have lost their lives. If asking people that have witnessed (or heard about) an accident scene (with sad consequences) if they would love to support a technology that could help prevent the loss of life on the road. The reasonable answer will be yes. But if asking these people what their support for the technology will be, if the technology has the potential to dangerously affect the economic well-being of their community, probably, at this point, the question may be going to a seemingly tough area for some people. Normally people will not want anything to affect the source of their income. It is known that the movement of vehicles from one place to the other does not come without other factors that have implications for the economy in various places around the world. To adequately address the issue of road traffic safety, there is also a need to address the economic implications for people in various regions. While there is concern about road traffic safety, there are also other concerns like the release of toxic gases into the atmosphere from various exhaust pipes.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) on the top ten causes of death [58], road traffic injuries were rated among the top 10 causes of death, killing 1.3 million people (76% of this are boys and men), just before tuberculosis (1.4 million), diarrhea (1.4 million), diabetes (1.6 million), lung cancer, including bronchus and trachea cancers (1.7 million), lower respiratory infections (3.2 million), heart diseases and stroke (15 million deaths) in 2015. Although there are other causes of death globally that exceed that of road traffic injuries, road traffic fatality is one that can be drastically reduced and eliminated by having effective changes to transportation policy. Because some autonomous technology systems in transportation that can help ensure that some human error during the driving task does not result in negative consequences are associated with other advanced technology that does not require the use of fossil fuel, to eliminate potential barriers to achieving improved road traffic safety, there is need to implement systems that will first assure those who make a living from sales of fossil fuel that the goal is not aimed at adversely affecting the economy of such nations.

It is known that fossil fuel resources in an area can be depleted after continuous mining over a long period of time. The Petroleum Technology Research Centre (PTRC) [59] described a project (that occurred between 2000 and 2012) that studied carbon dioxide injection and storage into two depleted oil fields in South-Eastern Saskatchewan. The injected CO2 is used for enhanced oil recovery. PTRC also noted that operators of oilfields in West Texas have been injecting carbon dioxide into oil fields for a long time now. Knowing that the world’s deposits of fossil fuel are not an infinite reserve, while the resource is being wisely extracted for daily use, there is a need to also ensure continuous support for the development of technologies that can use renewable energies.

Allowing for a gradual adjustment to economic situations while improving road traffic safety will be good. Instead of having a viewpoint that somewhat associates automobiles that have a good level of autonomy with automobiles that do not require the use of fossil fuel, a good collaboration between those who have high expertise in producing automobiles with advanced technologies to help ensure that human limitations do not result in negative consequences will be good. In the face of depleting ‘non-renewable energy’, in various municipalities, and the concern about possible economic shock from a drastic change to technologies that use non-renewable energy, it may be good to explore a quota system in which there will be a certain percentage of vehicles that are made that can use non-renewable energy for a pre-determined length of time, while each manufacturer also has a quota for vehicles that use renewable energy. The quotas may be periodically adjusted depending on the need and global concerns. However, the vehicles (either the ones that use fossil fuel or the ones that rely completely on renewable energies should all have a reasonable level of autonomous system) to ensure adequate crash avoidance. The quota system described is aimed at giving various economies the opportunity to adjust and have a smooth transition with global technological developments, and long-term realities of non-renewable resources.

2.8. Improvement in Road Traffic Safety: Few Examples

Measures to improve road traffic safety have been implemented in various places. While some acknowledgeable improvements have been made, road traffic crashes and fatalities are still a big challenge in many places. Places with low road traffic accidents as currently presented on world health rankings include Micronesia, Sweden, Kiribati, United Kingdom, Netherlands, Switzerland, Denmark, Norway, Spain, Japan, Singapore, Israel, Iceland, etc. [60]. As early as 1997, the Swedish parliament has the plan to eradicate road fatalities and injuries (vision-zero). In 1997, the Swedish parliament adopted the vision-zero policy as a new direction for road traffic safety [61]. The aim of the vision-zero policy is to reach a stage where no one will be seriously injured or killed due to traffic accidents. The design of the road transportation system should be based on these requirements.

Sweden’s roads have achieved a record of the world’s safety roads, with three out of every 100,000 people dying on the roads each year [62]. A report about traffic and road conditions in Micronesia indicates that speed limits are very low: in most places, speed limits are 20 miles per hour, and 15 miles per hour when children are present in school zones [63]. Among other things, a report [64] on how South Korea has drastically reduced road deaths indicated that comprehensive policies played a major role in the reduction in children’s deaths from road and traffic injuries. Transport safety acts, guidelines, and regulations were thoroughly revised and complemented as need be. Run-red and speeding cameras were installed on roadsides, and there was an improvement in transportation infrastructures such as new pavements, guardrails, and speed controls for various hazardous locations.

2.9. Pathway to Having a Smooth Transition in Transportation Policy to Reversing Deadly Trends in Road Traffic Safety

2.9.1. Engaging with the Community

-

Create more awareness about the severity of road traffic safety, and the need to take urgent actions.

-

Allow the general populace to contribute to the proposal for the improvement of road traffic safety.

-

Have a team of experts review the suggestions from the community and rate the suggestions.

-

Select the best proposal to improve road traffic safety in your community (lessons learned from other places with great improvement in road traffic safety may be taken into consideration).

-

Use established statistics from research, good reasoning, engineering judgment, and adequate logic to defend the selected proposals.

-

Ensure that those who are in charge of the decisions are people that are not biased, either in favor of a certain technology over another because of economic or political interests (i.e., allow the safety of people to rise above political or economic interests).

2.9.2. Using Research Records as a Defense for Policy Improvements

One of the traditional approaches to traffic safety is on the change in individual road user behavior [65]. It is known that humans have limitations in driving. Efforts to change human behaviors in driving have not achieved the desired goal to eliminate road traffic fatalities for many years. Meanwhile, technologies already exist to help ensure that human errors while driving do not result in negative consequences. To see the effective implementation of a policy that can bring about good change, the following recommendations may be used in various municipalities:

-

Call a meeting with the executives of all car manufacturers in the community.

-

Showcase the newest standards of collision avoidance features that can drastically reduce traffic collisions.

-

In the presence of all, ask to know if there is any car manufacturing company that is unable to produce vehicles that meet the standards for collision avoidance systems, regardless of the form of energy that is used to power such a vehicle.

-

Ensure a good collaboration among the automakers to assist anyone who does not have the technology or facility to meet up with the desired standard.

-

Ensure adequate compensation for those who came up with a technology that is beneficial to all and ensure that the technology is available for use by everyone to improve road traffic safety for all.

-

Ensure unbiased, and continuous testing of all the desirable technologies under every condition that a driver may see on the roads.

-

Make legislation that raises the minimum vehicle standards for all vehicles on the road in that jurisdiction.

-

Make legislation that disallows vehicles that do not meet the desired standards from being imported into the country.

-

Establish a deadline by which all vehicles on the road in that country or jurisdiction must have the minimum standard that is specified.

-

Ensure that adequate centers exist that will check to confirm that all vehicles in each municipality meet the minimum vehicle standards for automatic collision avoidance systems.

-

Ensure that the vehicle manufacturers can provide an upgrading service to existing vehicles to have the desirable collision avoidance systems.

-

Recommend that all vehicle owners take their vehicles to the car dealership for upgrades to the desirable collision avoidance systems.

-

Ensure legislation that mandates everyone in the municipality to either upgrade their vehicles to meet the minimum standard for collision avoidance systems or disallow such vehicles from the community. (A fine may be instituted for violation of the legislation).

-

Refuse to renew vehicle license for any vehicle that does not meet the minimum vehicle standard for collision avoidance systems on the road.

-

Ensure adequate enforcement, which may include a periodic search of any property that has a vehicle that does not meet up with the minimum standards for collision avoidance systems and disallow such vehicles.

The above strategy may be implemented by various task forces that are appointed by governments of nations that are interested in moving towards vision-zero for traffic collisions, injuries, property damage, and fatalities. It can also be used as a guide by subcommittees of legislative bodies that are appointed by various governments to oversee continuous improvements to vehicle standards. Note that except the fully autonomous vehicles are equipped with systems that are able to recognize environmental conditions in which their operations have not been adequately tested, and the safety of road users is guaranteed, (and also refuse to work in a fully autonomous version in such cases) good professional ethics may not allow the approval of fully autonomous vehicles for use in various communities on a large scale.

While there is news about notable achievements in the reduction in traffic crashes with policy improvements in some municipalities, there is still a need to put in more effort to achieve more improvement in road traffic safety in all jurisdictions globally.

-

A concerted effort is needed (cooperation between all nations on improvement to transportation safety).

-

Open sharing of knowledge on what has resulted in positive achievements (improvement) in road safety in various municipalities on a constant basis is recommended.

-

There is a need to legislate an increase to the minimum safety standard for all motor vehicles on the road.

-

There is a need to ensure that all manufacturers of motor vehicles are aware of the increased minimum safety standards for motor vehicles. Enforcement of these increased standards is recommended.

-

There is a need to create a sense of global accountability for road traffic safety for people in all jurisdictions. This should be strictly motivated by the intention to improve road traffic safety in all communities globally.

-

There is a need to set a timeline for various nations to come up with adequate legislation, and enforcement of legislation aimed to improve road traffic safety.

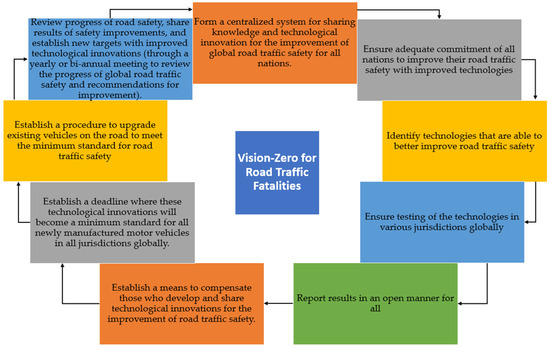

Some researchers [1] noted that further big successes in improving road traffic safety are only possible through a broad penetration of active safety and driver assistance systems that has great potential to reduce injury risks or fatalities on the roads. Broader penetration of active safety and driver assistance systems can be facilitated by periodic reviews of efficient innovative technologies to improve road traffic safety and subsequent legislation to increase the minimum standards for motor vehicles to reduce the impact of human errors on the road. Given various human limitations (which the present driver training and law enforcement have not been able to eradicate for many years) that affect the driving operation, and the fact that the achievement of zero traffic death is still a challenge in a lot of countries, it is high time for the world to explore the breakthrough idea to turn around from what presently appears to be an unending journey with road traffic fatalities in many places. The need to welcome a reasonable degree of autonomous motor vehicle technologies to ensure that human limitations in the driving of motor vehicles do not lead to negative consequences has been discussed in this report. This report recommends adequate testing of the technologies on a large scale in every community, in an open and unbiased way. This report also recommends that technologies that are found to be efficient in improving traffic safety be made as minimum standards for all motor vehicles on the road. A periodic and consistent review of the status of transportation safety standards and subsequent improvements to the standards is recommended in every community globally. A model for continuous improvement of road traffic safety as in Figure 1 will be beneficial in sharing knowledge about what has helped to improve road traffic safety in some jurisdictions and how others can benefit from it. The idea of vision-zero for road traffic fatalities is one that ought to be consistently pursued by all countries. With a prediction that indicates that the anticipated goals by the European Union as in vision-zero cannot be achieved within a 10-year period from 2015 to 2025, a previous work [66] reported that to achieve vision-zero, there is a need to explore more opportunities. Some other researchers [1] also noted that new technical concepts are needed for vision-zero.

Figure 1. Model for continuous improvement of road traffic safety on a global scale.

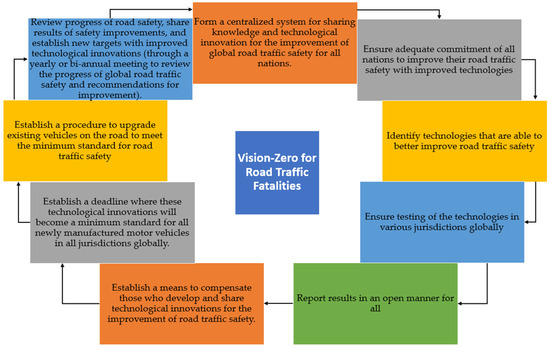

2.9.3. Actionable Strategies Towards the Achievement of Vison-Zero for Road Traffic Fatalities Globally

-

Form a centralized system for sharing knowledge and technological innovation for the improvement of global road traffic safety for all nations.

-

Ensure adequate commitment of all nations to improve their road traffic safety with improved technologies.

-

Identify technologies that are able to better improve road traffic safety.

-

Ensure testing of the technologies in various jurisdictions globally.

-

Report results in an open manner for all.

-

Establish a means to compensate those who develop and share technological innovations for the improvement of road traffic safety.

-

Establish a deadline where these technological innovations will become a minimum standard for all newly manufactured motor vehicles in all jurisdictions globally.

-

Establish a procedure to upgrade existing vehicles on the road to meet the minimum standard for road traffic safety.

-

Review progress of road safety, share results of road safety improvements, and establish new targets with improved technological innovations (through a yearly or a bi-annual meeting to review the progress of global road traffic safety and recommendations for improvement).

The effort to eradicate road traffic fatalities should not be just a one-time thing in which some standards are legislated, with no action taken to improve on the minimum vehicle standards for many years. Efforts to improve vehicle standards should be an ongoing event until the world is able to achieve a state where there will be no more fatalities on the roads globally. The goal to achieve zero fatalities on the road also extends beyond improving the functionalities of the vehicle to complement human errors in driving. There is a need to attend to issues from all other factors that interact during the driving operation. On a topic about complete street concepts and ensuring the safety of vulnerable road users, a scholar [67] mentioned various measures to improve road traffic safety for various factors that interact during motor vehicle driving operation (the road, the driver, the car, the environment, etc.). This report recommends a periodic meeting in a minimum of a 2-year interval to review global road traffic safety, examine what improvements in automobile technologies have yielded positive results, and what new improvements need to be implemented, to see better results. These meetings should be followed by new mandates to all car manufacturers to implement the suggested improvements in all automobiles. As there is an effort in improving the technology system for automobiles, it will also be good to see an agreement on a concerted effort to see improvement in the infrastructure systems for developing nations. Recall, good roads are also essential for road traffic safety everywhere.

References

- Schanz, A.E.; Hamann, R. Towards “Vision Zero”. In Proceedings of the SAE 2012 World Congress & Exhibition SAE International, Detroit, MI, USA, 24–26 April 2012; SAE International: Warrendale, PA, USA, 2012; ISSN 0148-7191. e-ISSN: 2688-3627.

- Sing, S. Critical Reasons for Crashes Investigated in the National Motor Vehicle Crash Causation Survey; National Center for Statistics and Analysis: Washington, DC, USA, 2018.

- Durić, P.; Miladinov-Mikov, M. Some characteristics of drivers having caused traffic accidents. Med. Pregl. 2008, 61, 464–469.

- Kaul, A.; Altaf, I. Vehicular adhoc network-traffic safety management approach: A traffic safety management approach for smart road transportation in vehicular ad hoc networks. Int. J. Commun. Syst. 2022, 35, e5132.

- Das, R.C.; Shfie, I.K.; Hamim, O.F.; Hoque, M.S.; Mcllroy, R.C.; Plant, K.L.; Stanton, N.A. Why do road traffic collision types repeat themselves? Look back before moving forward. Hum. Factors Ergon. Man. 2021, 31, 652–663.

- Bougna, T.; Hundale, G.; Taniform, P. Quantitative Analysis of the Social Costs of Road Traffic Crashes Literature. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2022, 165, 106282.

- Martins, M.A.; Garcez, T.V. A multidimensional and multi-period analysis of safety on roads. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2021, 162, 106401.

- Roess, R.P.; Prassas, E.S.; McShane, W.R. Traffic Engineering, 4th ed.; Pearson Higher Education, Inc.: Upper Saddle River, NJ, USA, 2011.

- Samani, A.R.; Mishra, S.; Dey, K. Assessing the effect of long-automated driving operation, repeated take-over requests, and driver’s characteristics on commercial motor vehicle drivers’ driving behavior and reaction time in highly automated vehicles. Transp. Res. F 2022, 84, 239–261.

- Xu, J.; Guo, K.; Sun, P.Z.H. Driving Performance Under Violations of Traffic Rules: Novice vs. Experienced Drivers. IEEE Trans. Intell. 2022, 7, 4.

- Liu, T.; Zhou, H.; Itoh, M.; Kitazaki, S. The Impact of Explanation on Possibility of Hazard Detection Failure on Driver Intervention under Partial Driving Automation. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium, IV, Changshu, China, 26–30 June 2018.

- European Commission. Ethics of Connected and Automated Vehicles. In Recommendations on Road Safety, Privacy, Fairness, Explainability and Responsibility; Independent expert report; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2020; ISBN 978-92-76-17867-5.

- Kong, Y.; Vine, S.L.; Liu, X. Capacity Impacts and Optimal Geometry of Automated Cars’ Surface Parking Facilities. J. Adv. Transp. 2018, 2018, 6908717.

- Palma, D.C.; Galdi, V.; Calderaro, V.; Luca, F.D. Driver Assistance System for Trams: Smart Tram in Smart Cities. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 2020 IEEE Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe, EEEIC/I and CPS Europe, Madrid, Spain, 9–12 June 2020.

- Connected Automated Driving.eu. France Takes Lead on Allowing Automated Driving on Public Roads. Available online: https://www.connectedautomateddriving.eu/blog/france-takes-lead-on-allowing-automated-driving-on-public-roads/ (accessed on 8 March 2023).

- Szucs, H.; Hezer, J. Road Safety Analysis of Autonomous Vehicles. An Overview. Period. Polytech. Transp. Eng. 2022, 50, 426–434.

- Vine, S.L.; Zolfaghari, A.; Polak, J. Autonomous cars: The tension between occupant experience and intersection capacity. Transp. Res. Part C Emerg. Technol. 2015, 52, 1–14.

- Jegham, I.; Khalifa, A.B.; Alouani, I.; Mahjoub, M.A. A novel public dataset for multimodal multiview and multispectral driver distraction analysis: 3MDAD. Signal Process. Image Commun. 2020, 88, 115960.

- Khan, A. Cognitive Connected Vehicle Information System Design Requirement for Safety: Role of Bayesian Artificial Intelligence. Comput. Sci. 2013, 11, 54–59.

- Tanaka, Y.; Okano, H.; Tanabe, S. Analysis of Haptic Interaction between Limbs in Operations of Vehicular Driving Interfaces. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE International Conference on Mechatronics and Automation, Takamatsu, Japan, 6–9 August 2017.

- Khatab, E.; Onsy, A.; Varley, M.; Abouelfarag, A. Vulnerable objects detection for autonomous driving: A review. Integration 2021, 78, 36–48.

- Gogri, M.; Hartstern, M.; Stork, W.; Winsel, T. A Methodology to Determine Test Scenarios for Sensor Constellation Evaluations. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 3rd Connected and Automated Vehicles Symposium, CAVS, Victoria, BC, Canada, 18 November–16 December 2020.

- Abe, G.; Sato, K.; Uchida, N.; Itoh, M. Effect of Changes in Levels of Automated Driving on Manual Control Recovery. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2019, 52, 79–84.

- Yoshino, K.; Yokoi, H. A basic study on a learning motor vehicle using basic elements for neural computer, continuous-time Folthrets. Neurocomputing 1998, 19, 59–76.

- Jamroz, K.; Smolarek, L. Driver Fatigue and Road Safety on Poland’s National Roads. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2013, 19, 297–309.

- Fletcher, A.; McCulloch, K.; Baulk, S.D.; Dawson, D. Countermeasures to driver fatigue: A review of public awareness campaigns and legal approaches. Centre for Sleep Research, University of South Australia. Aust. N. Z. J. Public Health 2007, 29, 471–476.

- European Transport Safety Council, Brussels. The Role of Driver Fatigue in Commercial Road Transport Crashes. 2001. Available online: http://etsc.eu/wp-content/uploads/The-role-of-driver-fatigue-in-commercial-road-transport-crashes.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2017).

- Brown, I.D. Driver Fatigue. Hum. Factors 1994, 36, 298–314.

- The Royal Society for the Prevention of Accidents (ROSPA). Driver Fatigue and Road Accidents. A Literature Review and Position Paper. 2001. Available online: https://www.rospa.com/rospaweb/docs/advice-services/road-safety/drivers/fatigue-litreview.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2017).

- Mello, M.T.D.; Narciso, F.V.; Tufik, S.; Paiva, T.; Spence, D.W.; Bahammam, A.S.; Verster, J.C.; Pandi-Perumal, S.R. Sleep Disorders as a Cause of Motor Vehicle Collisions. Int. J. Prev. Med. 2013, 4, 246–257.

- Kawanaka, H.; Miyaji, M.; Bhuiyan, M.S.; Oguri, K. Identification of Cognitive Distraction Using Physiological Features for Adaptive Driving Safety Supporting System. Int. J. Veh. Technol. 2013, 2013, 817179.

- Foss, R.D.; Goodwin, A.H. Distracted Driver Behaviors and Distracting Conditions among Adolescent Drivers: Findings from a Naturalistic Driving Study. J. Adolesc. Health 2004, 54, 5.

- Nagase, A.; Kawanaka, H.; Bhuiyan, M.S.; Oguri, K. Multi-class Identification of Driver’s Cognitive Distraction with Error-Correcting Output Coding (ECOC) Method. In Proceedings of the 12th International IEE Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems, St. Louis, MO, USA, 4–7 October 2009.

- Russell, S.; Radlbeck, J.; Atwood, J.; Schaudt, W.A.; McLaughlin, S. Headup Displays and Distraction Potential; Report No. DOT HS 813 293; National Highway Traffic Safety Administration: Washington, DC, USA, 2023.

- Morgenstern, T.; Wogerbauer, E.M.; Naujoks, F.; Krems, J.F.; Keinath, A. Measuring driver distraction—Evaluation of the box task method as a tool for assessing in-vehicle system demand. Appl. Ergon. 2020, 88, 103181.

- World Health Organization (WHO); NHTSA. Mobile Phone Use: A Growing Problem of Driver Distraction. 2011. Available online: http://www.who.int/violence_injury_prevention/publications/road_traffic/distracted_driving_en.pdf (accessed on 21 June 2017).

- Center for Disease and Control Prevention (CDC). Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/motorvehiclesafety/distracted_driving/index.html (accessed on 29 June 2017).

- Klinjun, N.; Kelly, M.; Praditsathaporn, C.; Petsirasan, R. Identification of Factors Affecting Road Traffic Injuries Incidence and Severity in Southern Thailand Based on Accident Investigation Reports. Sustainability 2021, 13, 22.

- American Association of State Highway and Transportation Officials, AASHTO. A Policy on Geometric Design of Highways and Streets, 5th ed.; AASHTO: Washington DC, USA, 2004.

- Decker, J.S.; Stannard, S.J.; Mcmanus, B.; Wittig, S.M.O.; Sisopiku, V.P.; Stavrinos, D.; PMC; NCBI. The Impact of Billboards on Driver Visual Behavior: A Systematic Literature Review. 2015. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4411179/ (accessed on 30 June 2017).

- Young, M.S.; Mahfoud, J.M. Driven to Distraction: Determining the Effect of Roadside Advertisement on Driver Attention. Ergonomics Research Group, School of Engineering and Design, Brunel University. 2007. Available online: http://www.reesjeffreys.co.uk/reports/Roadside%20distractions%20final%20report%20%28Brunel%29.pdf (accessed on 29 June 2017).

- Kuypers, K.P.C.; Legrand, S.-A.; Ramaekers, J.G.; Verstraete, A.G. A Case-Control Study Estimating Accident Risk for Alcohol, Medicines and Illegal Drugs. PLoS Med. 2012, 7, e43496.

- Bradford, A. What is THC. Live Science. 2017. Available online: https://www.livescience.com/24553-what-is-thc.html (accessed on 28 June 2017).

- National Institute of Drug Abuse. “Marijuana”. 2017. Available online: https://www.drugabuse.gov/publications/drugfacts/marijuana (accessed on 28 June 2017).

- Brubacher, J.R. Cannabis and motor vehicle crashes. BCMJ 2011, 53, 6.

- Sewell, R.A.; Poling, J.; Sofuoglu, M. The Effect of Cannabis Compared with Alcohol on Driving. PMC. US National Library of Medicine. National Institute of Health. 2009. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2722956/ (accessed on 28 June 2017).

- Srisurin, P.; Chalermpon, S. Analyzing Human, Roadway, Vehicular and Environmental Factors Contributing to Fatal Road Traffic Crashes in Thailand. Eng. J. Thai. 2021, 25, 27–38.

- Ran Naor Foundation for Advancement of Road Safety Research. “Road Traffic Safety Research and Education in Israel”. 2007. Available online: http://www.rannaorf.org.il/webfiles/files/Road%20traffic%20safety%20research.pdf (accessed on 5 July 2017).

- Mofolasayo, A. Evaluation of Potential Policy Issues When Planning for Autonomous Vehicles. In Proceedings of the 53rd Annual Conference, Canadian Transportation Research Forum, Gatineau, QC, Canada, 3–6 June 2018; Available online: https://ctrf.ca/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/CTRF_2018_Mofolasayo_6_1.pdf (accessed on 13 March 2023).

- US Department of Transportation (USDOT); National Highway Traffic Safety Administration (NHTSA). “Federal Automated Vehicles Policy. Accelerating the Next Revolution in Roadway Safety”. 2016. Available online: https://www.transportation.gov/sites/dot.gov/files/docs/AV%20policy%20guidance%20PDF.pdf (accessed on 25 February 2017).

- Daziano, R.A.; Sarrias, M.; Leard, B. Are consumers willing to pay to let cars drive for them? Analysing response to Autonomous vehicles. Transport Res. C-Emer. 2017, 78, 150–164.

- Kyriakidis, M.; Happee, R.; Winter, J.C.F.D. Public opinion on automated driving: Results of an international questionnaire among 5000 respondents. Transp. Res. F Traffic Psychol. Behav. 2015, 32, 127–140.

- Kettwich, C.; Schrank, A.; Avsar, H.; Oehl, M. A Helping Human Hand: Relevant Scenarios for the Remote Operation of Highly Automated Vehicles in Public Transport. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4350.

- Suzuki, R.; Madokoro, H.; Nix, S.; Kazuki, S.; Saruta, K.; Saito, T.K.; Sato, K. Readiness Estimation for a Take-Over Request in Automated Driving on an Expressway. In Proceedings of the 22nd International Conference on Control, Automation and Systems, Busan, Republic of Korea, 27 November–1 December 2022.

- Mutzenich, C.; Durant, S.; Helman, S.; Dalton, P. Updating our understanding of situation awareness in relation to remote operators of autonomous vehicles. Cogn. Res. Princ. Implic. 2021, 6, 9.

- SAE International TM. Automated Driving. Levels of Driving Automation Are Defined in New SAE International Standard J3016. 2014. Available online: http://www.sae.org/misc/pdfs/automated_driving.pdf (accessed on 11 March 2017).

- Minaki, R. Experimental verification of man-machine interface based on electric power steering control for advanced driver assistance system. In Proceedings of the 31st International Electric Vehicle Symposium and Exhibition, EVS 2018 and International Electric Vehicle Technology Conference 2018, EVTeC, Kobe, Japan, 30 September–3 October 2018.

- World Health Organization (WHO). “The Top 10 Causes of Death”. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs310/en/ (accessed on 27 June 2017).

- Petroleum Technology Research Center (PTRC). “Weyburn-Midale—The IEAGHG Weyburn-Midale CO2 Monitoring and Storage Project”. Available online: https://ptrc.ca/projects/weyburn-midale (accessed on 28 June 2017).

- World Health Rankings. Road Traffic Accidents. Available online: https://www.worldlifeexpectancy.com/cause-of-death/road-traffic-accidents/by-country/ (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Kristianssen, A.-C.; Andersson, R.; Belin, M.-A.; Nilsen, P. Swedish Vision Zero policies for safety—A comparative policy content analysis. Saf. Sci. 2018, 103, 260–269.

- The Economis. Why Sweden Has So Few Road Deaths. 2014. Available online: https://www.economist.com/the-economist-explains/2014/02/26/why-sweden-has-so-few-road-deaths (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Country Reports-Travel Edition. Traffic and Road Conditions in Micronesia. Available online: https://www.countryreports.org/travel/Micronesia/traffic.htm (accessed on 27 April 2019).

- Sung, N.M.; Ríos, M.O.; World Economic Forum. “How South Korea Has Dramatically Reduced Road Deaths”. World Bank. 2015. Available online: https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2015/06/how-south-korea-has-dramatically-reduced-road-deaths/ (accessed on 28 June 2017).

- Transportation Association of Canada, TAC. Vision Zero and the Safe System Approach: A Primer for Canada. Transportation Association of Canada. 2023. Available online: https://www.tac-atc.ca/sites/default/files/site/doc/publications/2023/prm-vzss-e.pdf (accessed on 24 October 2023).

- Hosse, R.S.; Becker, U.; Manz, H. Grey Systems Theory Time Series Prediction applied to Road Traffic Safety in Germany. IFAC-PapersOnLine 2016, 49, 231–236.

- Mofolasayo, A. Complete Street Concept, and Ensuring Safety of Vulnerable Road Users. In Proceedings of the World Conference on Transport Research—WCTR 2019, Mumbai, India, 26–31 May 2020.

More

Information

Subjects:

Transportation

Contributor

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

4.3K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

02 Feb 2024

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No