You're using an outdated browser. Please upgrade to a modern browser for the best experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Maria J. Melo | -- | 1682 | 2024-01-16 14:09:49 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 1682 | 2024-01-17 02:30:38 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Vieira, M.; Melo, M.J.; Nabais, P.; Lopes, J.A.; Lopes, G.V.; Fernández, L.F. The Colors in Medieval Illuminations of Alfonso X. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/53906 (accessed on 05 January 2026).

Vieira M, Melo MJ, Nabais P, Lopes JA, Lopes GV, Fernández LF. The Colors in Medieval Illuminations of Alfonso X. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/53906. Accessed January 05, 2026.

Vieira, Márcia, Maria João Melo, Paula Nabais, João A. Lopes, Graça Videira Lopes, Laura Fernández Fernández. "The Colors in Medieval Illuminations of Alfonso X" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/53906 (accessed January 05, 2026).

Vieira, M., Melo, M.J., Nabais, P., Lopes, J.A., Lopes, G.V., & Fernández, L.F. (2024, January 16). The Colors in Medieval Illuminations of Alfonso X. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/53906

Vieira, Márcia, et al. "The Colors in Medieval Illuminations of Alfonso X." Encyclopedia. Web. 16 January, 2024.

Copy Citation

The intellectual action associated with Alfonso X, king of the Crown of Castile (r. 1252-84), known as the Learned, is one of the most brilliant cultural enterprises of the medieval West.

color palette

brazilwood lake pigments

Songs of Holy Mary

painting technique

1. Illuminated Manuscripts Produced in the Scriptorium of Alfonso X

The intellectual action associated with Alfonso X, king of the Crown of Castile (r. 1252-84), known as the Learned, is one of the most brilliant cultural enterprises of the medieval West. This sophisticated project was articulated by specialized groups working in different fields of knowledge (history, astronomy and astrology, literature, hagiography, and law) to find and translate numerous sources (in Latin, Arabic, or Hebrew) into Castilian (old Spanish) and Galician-Portuguese, and to compose new works to serve the political and personal interests of the monarch. These works took the form of extraordinary books made by professional teams of copyists and illuminators who worked in coordination with the text’s authors under the orders of the king, who played an active role in their commission and production [1][2][3][4].

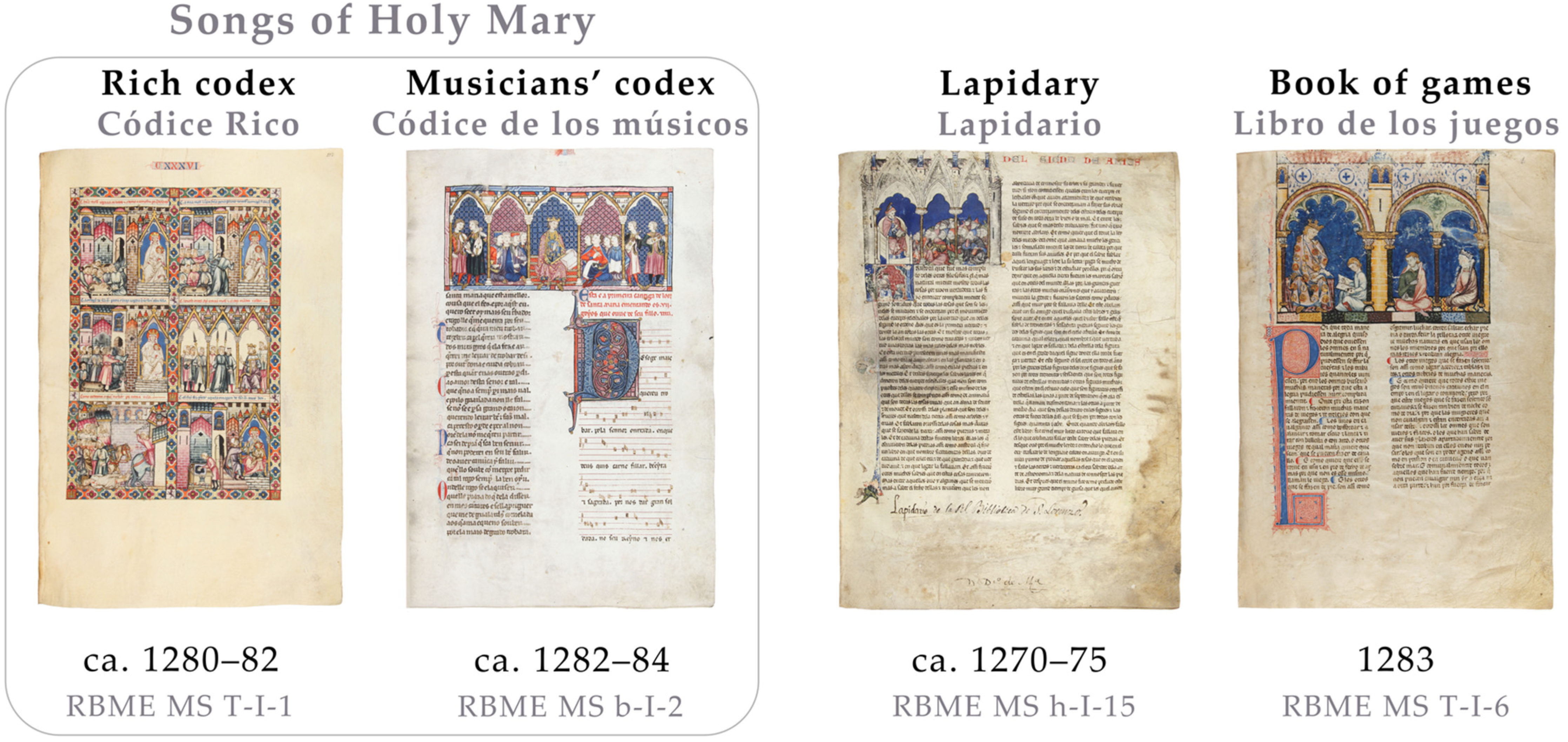

This ambitious project has left us with a large number of manuscripts that, when studied together, reveal common features as they were produced in the royal scriptorium. These manuscripts and their textual and visual content much better today. However, many unknowns exist about their execution, especially technical aspects such as the type of materials and pigments used and the painting technique. Their study may shed some light on the production of manuscripts within an Iberian court in a highly sophisticated scriptorium. To clarify the color palette used in Alfonso’s scriptorium, four manuscripts from the Royal Library of the El Escorial Monastery (Spain) have been analyzed, Figure 1; two manuscripts of the so-called Songs of Holy Mary (Cantigas de Santa Maria), a set of religious songs praising the Virgin Mary and depicting her miracles, the Rich codex (Códice Rico, T-I-1), and the Musicians’ codex (Códice de los músicos, b-I-2); the Lapidary (Lapidario, h-I-15), a manuscript of scientific content that analyzes minerals and their applications in relation to the influence of the stars, and the Book of Games (Libro de los juegos, T-I-6), a treatise that analyzes different types of games from a social perspective.

Figure 1. Four manuscripts from the Royal Library of the El Escorial Monastery (Spain) were studied to uncover the color palette in Alfonso’s scriptorium. Except for the Book of Games, which is dated, the other manuscripts have an approximate dating: Rich codex, ca. 1280–1282, Musicians’ codex, ca. 1282–1284, Lapidary, ca. 1270–1275.

It is possible that it was created in royal or noble Iberian courts at the beginning of the 14th century or in the last decade of the 13th century. Indisputable points of contact between these Alfonsine codices and the Ajuda Songbook exist. Therefore, the comparative study between these manuscripts may prove relevant.

2. Establishing a Chronology through Natural Dyes in Illuminated Manuscripts—The Brazilwood Case

Regarding carmines and roses from brazilwood, the currently accepted chronology would be from the end of the 13th century/beginning of the 14th century until the 16th century [5][6][7][8]. In this context and according to contemporary sources, the pink color produced from brazilwood is a luxury color [9].

These pigments were applied as colors using a binding media called tempera at the time. These tempera in medieval times and in medieval illuminations are based on: (1) proteins (e.g., collagen-based; glair, egg yolk); (2) polysaccharides (e.g., gum arabic, mesquite gum); and (3) mixed tempera (proteinaceous + gums). Quoting Stefanos Kroustallis, “El término latín “temperare” (...) definían el proceso de mezclar un color con su aglutinante en una disolución o emulsión acuosa y así se emplea en los tratados medievales de tecnología artística cuando se trata la preparación de los colores para la “pictura librorum” [10]”. To know more, please see [11].

2.1. French Books of Hours in Portuguese Collections

Some of the brazilwood-based colors used in the books of hours can be reproduced using the recipes described in the book on how to make all the color paints for illuminating books (abbreviated as book of all color paints) [12][13]. Three formulations were identified in the pinks of the books of hours based on the fluorescence spectra in the visible. For this analysis, 80 emission and 80 excitation spectra were acquired in 18 brazilwood-based colors from 8 illuminated manuscripts produced between the 13th and 15th centuries. The formulations were designated BW1, 2, and 3 [13]. The color BW1 has the presence of calcium carbonate and lead white. In BW2 and BW3, calcium carbonate is accompanied by gypsum. The two colors are distinguished due to a higher proportion of gypsum in BW3. Furthermore, it was possible to compare and analytically match BW 1 and BW 3 with two recipes from the book of all color paints [13]. This was confirmed through their infrared spectra. To know more about these books of hours, see [13].

2.2. Ajuda Songbook’s Pinks

Scientific analysis showed, for the light pinks in the Ajuda Songbook, a different formulation from that found in fifteenth-century books of hours and from all historical reconstructions of these colors prepared to date, Figure 2. In the pink color of Ajuda Songbook, in addition to the brazilwood lake pigment, lead white was also identified, which lightens the color, alongside calcium carbonate that is used as a filler. The binding media is based on mesquite gum [9]. These components are necessary for the stability and durability of the paint. An additive such as calcium carbonate is added in a proportion that does not alter its hue, sometimes improving color perception by increasing opacity. Furthermore, its presence improves the mechanical stability of the paint. It is interesting to note that, nowadays, it remains a filler commonly found in paint formulations, including high-quality ones such as artist pigments.

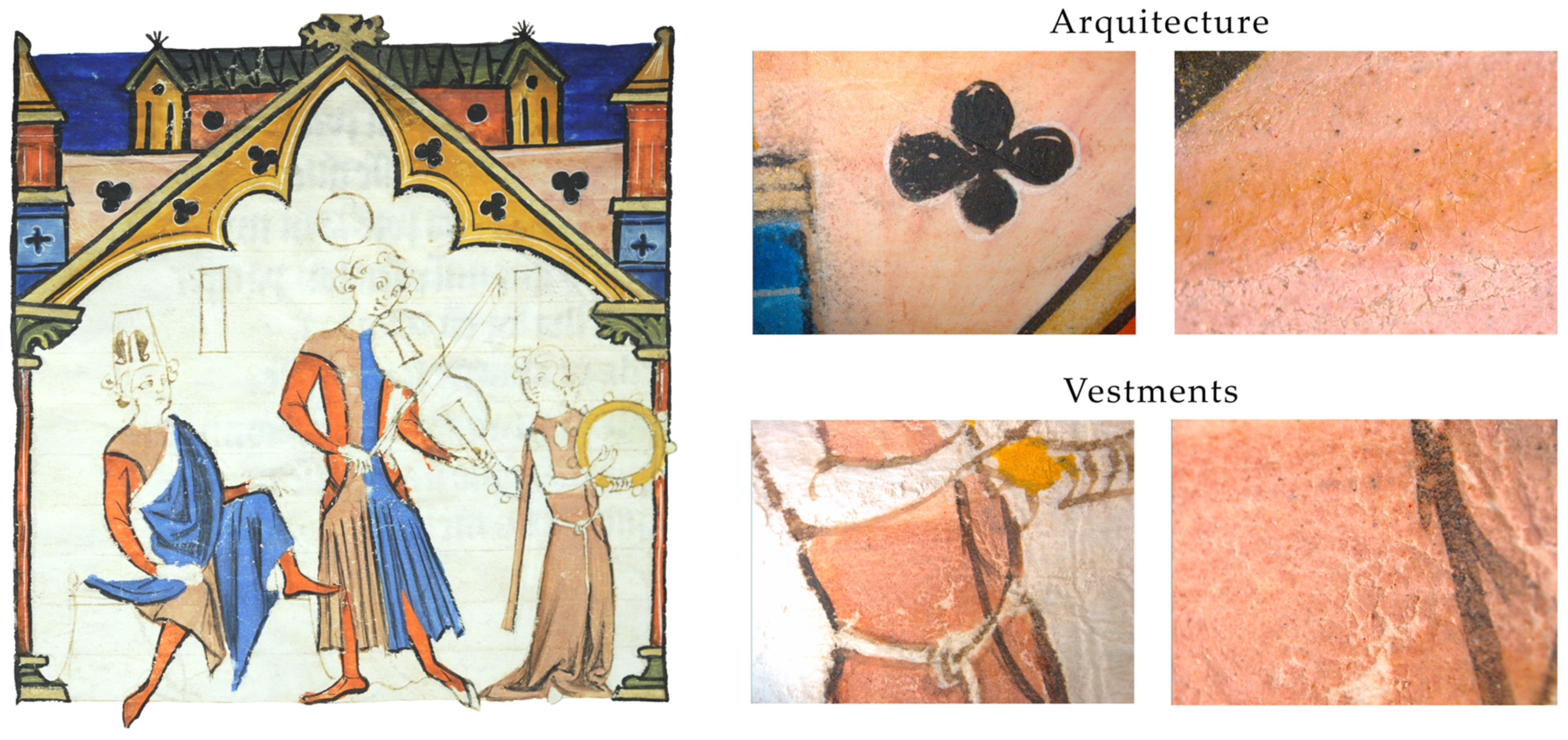

Figure 2. The pink colors in the Ajuda Songbook have a specific formulation. Details of these pinks in the architectural background and vestments (folio 21).

These pinks were applied to the architectural backgrounds and musical scenes, particularly in the aristocratic clothing [14]. Five shades of pink were studied from the garments used in folios 16r, 17r, 21r, 40v, and 59r, including three folios from Évora (fols. 16r, 17r, 40v) (While most of the manuscript of the Ajuda Songbook was found in Colégio dos Nobres in Lisbon at the beginning of the nineteenth century, a quire and loose folios were found in Biblioteca Pública de Évora, in 1842. These were then integrated into the main manuscript, but the existence of these loose folios points out to the location of the Ajuda Songbook in Évora at a certain point in history [9][14]). Unlike the architectural background, the musical scenes are unfinished. Differences were found in the additives when compared to the pinks used in architecture. The translucent rose was prepared as paint, using the same formulation from the architectural backgrounds. The correct proportions were determined through infrared spectra as translucent pink brazilwood lake pigment (0.4%), lead white (19.9%), calcium carbonate (4.9%), and mesquite gum (74.8%). For a more in-depth analysis, see [9][13][15].

An orcein-based purple was also identified on pages 1, 12, 13, 31, and 55. These complex purples are extracted from various lichen species [16]. These pages are included in the Lineage book, dated to the fourteenth century, and are bound with the Ajuda Songbook. They were used in the filigreed initials of the Lineage book. To know more about its identification, please see [16].

3. Brazilwood Trade during the Kingdom of Alfonso X

Brazilwood has been imported to Europe from Asia as Biancaea sappan since at least the 12th century, probably earlier, being introduced by the Islamic world into the Iberian Peninsula through the silk trade [17][18][19]. Its main use was possibly related to textile production. Still, the work carried out in recent years also proves its use in manuscript illuminations [14][20][21][22]. In the Iberian Peninsula, documentation proves the commercialization and circulation of brazilwood since the 13th century in the territories of Castile and Aragon [23]. The oldest record is a document relating to the customs duties of the Crown of Aragon, dated 1243. Even more intriguing are the privileges granted to the city of Murcia, issued on 18 May 1267 and then ratified on 28 April 1272, which express that the inhabitants of the city of Murcia can acquire and use any dye except indigo, lac dye, cochineal, and brazilwood since these were to be used only in textile production carried out in a cauldron managed by the court. However, in 1313 and 1322, a request was made to Alfonso XI to lift the ban on using these materials by the population, as was done in other places, claiming that the cauldron for royal textile production had never existed. Regardless of whether the monopoly on these dyes was effective, this information is important because it shows the use and commercialization of these colors [23]. According to Partearroyo Lacaba, the supply of brazilwood was interrupted in 1453 with the capture of Constantinople by the Turks [17]. The Portuguese resumed the commerce of the dye in 1500 in Brazil, using a different tree species, Paubrasilia echinata [24].

These accounts provide evidence that brazilwood was present in Iberian commerce since early medieval times and that being a luxury material [25], there was a clear wish from the Castilian crown to monopolize its production and use [23].

4. A Multi-Analytical Approach for the Study of Colors in Medieval Manuscripts

In a paint, there are several essential components: the colorant, the tempera, and the additives, which may have suffered degradation, depending on the history of the manuscript [15][26][27]. So, the paints of Alfonso X manuscripts were first analyzed using optical microscopy (magnifying from 7× to 80×) to understand how the final color was built up and to detect possible degradation phenomena (loss of adhesion to the support, changes in color, etc.). The complete identification of the paint requires molecular techniques such as infrared and Raman spectroscopy [15][20][28][29][30][31][32][33][34]. It is complemented with elemental analysis using energy-dispersive X-ray fluorescence microspectrometry (microXRF) whenever possible. Using microXRF, elements are detected and semi-quantified. sis area, make it possible to selectively excite different paint components, thus simplifying the interpretation of the spectra [15]. However, these types of equipment are only available in the laboratory. In future work, the complex formulations used in these colors will be explored using infrared and Raman spectra as well as fluorescence spectra in the visible [13][14][15][21].

References

- Fernández Fernández, L. El Scriptorium Alfonsí: Coordenadas de Estudio. In Alfonso X el Sabio: Cronista y Protagonista de su Tiempo; Fidalgo, E., Ed.; Cilengua: San Millán de la Cogolla, Spain, 2020; Volume 1, pp. 89–114. ISBN 8418088070.

- Fernández Fernández, L. De Escriptos e Libros: Los Manuscritos de Alfonso X. In Alfonso X. El Universo Político y Cultural de un Reinado; Otín, M.J.L., Igual, D., Gómez, Ó.L., Eds.; Universidad de Castilla la Mancha: Toledo, Spain, 2023; in press.

- Kennedy, K. Alfonso X of Castile-León: Royal Patronage, Self-Promotion and Manuscripts in Thirteenth-Century Spain; Amsterdam University Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 1, ISBN 9789048541386.

- Bango, I. Alfonso X El Sabio; Región de Murcia: Murcia, Spain, 2009; ISBN 9788475645223.

- Pastoureau, M. Jésus Chez Le Teinturier: Couleurs et Teintures Dans L’occident Médiéval; Le Léopard d’or: Paris, France, 2000; ISBN 9782863771501.

- Daveri, A.; Doherty, B.; Moretti, P.; Grazia, C.; Romani, A.; Fiorin, E.; Brunetti, B.G.; Vagnini, M. An Uncovered XIII Century Icon: Particular Use of Organic Pigments and Gilding Techniques Highlighted by Analytical Methods. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2015, 135, 398–404.

- Edwards, H.G.M.; Farwell, D.W.; Newton, E.M.; Rull Perez, F.; Jorge Villar, S. Raman Spectroscopic Studies of a 13th Century Polychrome Statue: Identification of a “forgotten” Pigment. J. Raman Spectrosc. 2000, 31, 407–413.

- Karapanagiotis, I.; Daniilia, S.; Tsakalof, A.; Chryssoulakis, Y. Identification of Red Natural Dyes in Post-Byzantine Icons by HPLC. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2005, 28, 739–749.

- Vieira, M.; Nabais, P.; Hidalgo, R.J.D.; Melo, M.J.; Pozzi, F. The Only Surviving Medieval Codex of Galician-Portuguese Secular Poetry: Tracing History through Luxury Pink Colors. Herit. Sci. 2023, 11, 37.

- Kroustallis, S. Quomodo Decoratur Pictura Librorum, Materiales y Técnicas de La Iluminación Medieval. Anu. Estud. Mediev. 2011, 41, 775–802.

- Kroustallis, S. Binding Media in Medieval Manuscript Illumination: A Source of Research. Rev. História Arte 2011, 1, 113–125. Available online: https://revistadehistoriadaarte.files.wordpress.com/2011/09/art08.pdf (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Melo, M.J.; Castro, R.; Nabais, P.; Vitorino, T. The Book on How to Make All the Colour Paints for Illuminating Books: Unravelling a Portuguese Hebrew Illuminators’ Manual. Herit. Sci. 2018, 6, 44.

- Nabais, P.; Melo, M.J.; Lopes, J.A.; Vieira, M.; Castro, R.; Romani, A. Organic Colorants Based on Lac Dye and Brazilwood as Markers for a Chronology and Geography of Medieval Scriptoria: A Chemometrics Approach. Herit. Sci. 2021, 9, 32.

- Nabais, P.; Castro, R.; Lopes, G.V.; Sousa, L.C.; Melo, M.J. Singing with Light: An Interdisciplinary Study on the Medieval Ajuda Songbook. J. Mediev. Iber. Stud. 2016, 8, 283–312.

- Melo, M.J.; Nabais, P.; Vieira, M.; Araújo, R.; Otero, V.; Lopes, J.; Martín, L. Between Past and Future: Advanced Studies of Ancient Colours to Safeguard Cultural Heritage and New Sustainable Applications. Dye Pigment. 2022, 208, 110815.

- Melo, M.J.; Nabais, P.; Guimarães, M.; Araújo, R.; Castro, R.; Oliveira, M.C.; Whitworth, I. Organic Dyes in Illuminated Manuscripts: A Unique Cultural and Historic Record. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. A Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2016, 374, 20160050.

- Partearroyo Lacaba, C. Estudio Histórico-Artístico de Los Tejidos de al-Andalus y Afines. Bienes Cult.—Tejidos Hisp. 2005, 5, 37–74.

- Cardon, D. Natural Dyes: Sources, Tradition, Technology and Science; Archetype: London, UK, 2007; ISBN 9781904982005.

- Bechtold, T.; Mussak, R. Handbook of Natural Colorants; Bechtold, T., Mussak, R., Eds.; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2009; ISBN 9780470511992.

- Melo, M.J.; Otero, V.; Vitorino, T.; Araújo, R.; Muralha, V.S.F.; Lemos, A.; Picollo, M. A Spectroscopic Study of Brazilwood Paints in Medieval Books of Hours. Appl. Spectrosc. 2014, 68, 434–443.

- Roger, P.; Villela-Petit, I.; Vandroy, S. Les Laques de Brésil Dans l’enluminure Médiévale. Stud. Conserv. 2003, 48, 155–170.

- Vitorino, T.; Melo, M.J.; Carlyle, L.; Otero, V. New Insights into Brazilwood Lake Pigments Manufacture through the Use of Historically Accurate Reconstructions. Stud. Conserv. 2016, 61, 255–273.

- Fernández Fernández, L.; Melo, M.J.; Vieira, M. Pigmentos Para Un Rey: El Rosa de “palo Brasil” En La Paleta Cromática de Los Manuscritos de Alfonso X. In El Libro Manuscrito Medieval: Del Pergamino al Metadato; Editorial Dykinson: Madrid, Spain, 2023; in press.

- Jansen, P. Dyes and Tannins 3: Plant Resources of Tropical Africa; Jansen, P., Cardon, D., Eds.; PROTA Foundation: Wageningen, The Netherlands, 2005; Volume 3, ISBN 9789057821592.

- Dunlop, L.J.V. The Use of Colour in Parisian Manuscript Illumination c.1320–c.1420 with Special Reference to the Availability of Pigments and Their Commerce at That Period. Ph.D. Thesis, Faculty of Arts, University of Manchester, Manchester, UK, 1988.

- Melo, M.J.; Nabais, P.; Araújo, R.; Vitorino, T. The Conservation of Medieval Manuscript Illuminations: A Chemical Perspective. Phys. Sci. Rev. 2019, 4, 20180017.

- Melo, M.J.; Castro, R.; Miranda, A. Colour in Medieval Portuguese Manuscripts: Between Beauty and Meaning. In Science and Art: The Painted Surface; Sgamellotti, A., Brunetti, B.G., Miliani, C., Eds.; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 9781849738187.

- Coupry, C. A La Recherche des Pigments. Rev. História Arte 2011, 1, 127–136. Available online: https://revistadehistoriadaarte.files.wordpress.com/2011/09/art09.pdf (accessed on 5 September 2023).

- Knipe, P.; Eremin, K.; Walton, M.; Babini, A.; Rayner, G. Materials and Techniques of Islamic Manuscripts. Herit. Sci. 2018, 6, 55.

- Orna, M. March of the Pigments: Color History, Science and Impact, 1st ed.; Royal Society of Chemistry: London, UK, 2022; Volume 1, ISBN 9781839163159.

- Doherty, B.; Daveri, A.; Clementi, C.; Romani, A.; Bioletti, S.; Brunetti, B.; Sgamellotti, A.; Miliani, C. The Book of Kells: A Non-Invasive MOLAB Investigation by Complementary Spectroscopic Techniques. Spectrochim. Acta A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2013, 115, 330–336.

- Ricciardi, P.; Pallipurath, A.; Rose, K. “It’s Not Easy Being Green”: A Spectroscopic Study of Green Pigments Used in Illuminated Manuscripts. Anal. Methods 2013, 5, 3819–3824.

- Panayotova, S.; Ricciardi, P. Manuscripts in the Making: Art & Science; Panayotova, S., Ricciardi, P., Eds.; Harvey Miller Publishers: London, UK, 2017; Volume I and II, ISBN 9781909400108, 9781912554133.

- Salvadó, N.; Butí, S.; Cotte, M.; Cinque, G.; Pradell, T. Shades of Green in 15th Century Paintings: Combined Microanalysis of the Materials Using Synchrotron Radiation XRD, FTIR and XRF. Appl. Phys. A Mater. Sci. Process. 2013, 111, 47–57.

More

Information

Subjects:

Cultural Studies

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

756

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

17 Jan 2024

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No