Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Manuel Burelo | -- | 2995 | 2024-01-15 18:16:21 | | | |

| 2 | Camila Xu | Meta information modification | 2995 | 2024-01-16 02:17:40 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Burelo, M.; Martínez, A.; Hernández-Varela, J.D.; Stringer, T.; Ramírez-Melgarejo, M.; Yau, A.Y.; Luna-Bárcenas, G.; Treviño-Quintanilla, C.D. Bio-Based Polyurethane Elastomers. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/53849 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Burelo M, Martínez A, Hernández-Varela JD, Stringer T, Ramírez-Melgarejo M, Yau AY, et al. Bio-Based Polyurethane Elastomers. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/53849. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Burelo, Manuel, Araceli Martínez, Josué David Hernández-Varela, Thomas Stringer, Monserrat Ramírez-Melgarejo, Alice Y. Yau, Gabriel Luna-Bárcenas, Cecilia D. Treviño-Quintanilla. "Bio-Based Polyurethane Elastomers" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/53849 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Burelo, M., Martínez, A., Hernández-Varela, J.D., Stringer, T., Ramírez-Melgarejo, M., Yau, A.Y., Luna-Bárcenas, G., & Treviño-Quintanilla, C.D. (2024, January 15). Bio-Based Polyurethane Elastomers. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/53849

Burelo, Manuel, et al. "Bio-Based Polyurethane Elastomers." Encyclopedia. Web. 15 January, 2024.

Copy Citation

Elastomers, a category of polymers characterized by high elasticity and viscoelasticity, possess the ability to revert to their initial form after undergoing stretching or deformation and are known for their outstanding resistance to abrasion, tearing, and impact.

bio-based elastomer

rubbers

polyurethane

polyester

polyether

elastomeric properties

1. Introduction

According to PlasticsEurope AISBL©, the global plastics production data in 2021 was 390.7 Mt, and in 2022, it was 400.3 Mt; where Africa produced 9%, Europe 14%, America 21%, and Asia 56%, with China being the country with the highest plastic production, with about 32%. These include conventional plastics and thermoplastics such as PET, PE, PP, PVC, PS, and PU, as well as some thermoset plastics [1][2]. The production and consumption of conventional plastics and polymers show an increase year after year.

Elastomers, a category of polymers characterized by high elasticity and viscoelasticity, possess the ability to revert to their initial form after undergoing stretching or deformation and are known for their outstanding resistance to abrasion, tearing, and impact. Elastomers find applicability across various industries, including automotive, aerospace, construction, electronics, healthcare, and biomedicine [3][4][5]. There are two types of elastomers: thermoplastic elastomers (TPEs) (e.g., thermoplastic polyester elastomers, thermoplastic polyether elastomers, thermoplastic polyurethane elastomer, thermoplastic polyamide elastomers) and thermosets (e.g., vulcanized natural or industrial rubber, epoxidized natural rubber, cross-linked polyester elastomers, cross-linked polyurethane elastomers). Thermoset elastomers predominate in production and consumption. The elastomer industry encompasses three primary kinds: rubber, plastic, and gel. Rubber elastomers, crafted from natural or synthetic polymers, are renowned for their remarkable elasticity and durability. In contrast, plastic elastomers or TPE represent a fusion of rubber and plastic, delivering a harmonious combination of flexibility and rigidity [3][4]. Currently, polymers, including elastomers, are non-recyclable and come from non-renewable sources [5]. Due to this, the synthesis of elastomers from natural and renewable resources has attracted the attention of researchers and industries.

By the definition provided by the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC), the term “bio-based” refers to “materials that are either entirely or partially composed of biological products originating from biomass. This encompasses materials derived from plant, animal, marine, or forestry sources” [6]. In environmental terms, bio-based polymers possess the capacity to mitigate greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions, particularly carbon dioxide (CO2). This reduction occurs because, during the synthesis process using natural resources as raw materials, plants absorb atmospheric CO2 for their growth. As a result, bio-based polymers contribute to a net reduction in atmospheric CO2 levels [7].

A bio-based polymer originates from natural and/or renewable sources, typically derived from biomass, and is recognized for its environmentally friendly characteristics. It exhibits a shorter environmental decomposition time, influenced by both abiotic and biotic factors [8]. This polymer or elastomer may consist partially or entirely of bio-based components, such as a mixture, composite, copolymer, graft, additive, or by employing natural monomers in the synthesis (biopolymer). A higher percentage of bio-based content indicates a more sustainable material, often associated with biodegradable and compostable behavior [9].

2. Bio-Based Elastomers from Natural and Industrial Rubbers

Synthetic elastomers used in tires are derived mainly from petrochemicals, which are not sustainable. Recently, renewable resources have been used to produce several bio-based elastomers. For example, itaconic acid is a renewable resource from fermentations produced by microorganisms, especially Aspergillus terreus; it is used as a bio-based building block. Lei et al. have manufactured silica/poly(di-n-butyl itaconate-co-butadiene) (20–80% butadiene) nanocomposite-based green tires that are prepared by redox-initiated copolymerization of di-n-butyl itaconate and butadiene. These bio-based elastomers have excellent wet skid and low roll resistances, respectively [10].

It is essential to say that not all bio-based polymers are biodegradable (capability of being degraded by biological activity); for example, bio-based plastics such as the bio-polyethylene (Bio-PE) and Bio-poly(ethylene terephthalate) (Bio-PET) that use bioethanol from sugarcane (by the fermentation of glucose) [8][11][12], starch-based crops produced by wet-mill processing as raw material [13][14], the chemical modification of natural rubbers (NR) that have been modified to improve their properties and application, as well as the epoxidized NR under strain-induced crystallization (SIC) [15], are all non-biodegradable polymers.

In particular, natural rubber (NR) is a polymer composed of isoprene units linked to form double bonds with a cis configuration (99.9%, cis-1,4-polyisoprene) when extracted from the latex of the Hevea brasiliensis trees and Parthenium argentatum woody shrub [16][17][18]; trans configuration extracted from the latex of the Palaquium gutta trees (trans-1,4-polyisoprene) [17][19]; and cis/trans isomer mixtures extracted from the latex of the Manilkara zapota trees [17][18][20]. NR (99.9%, cis-1,4-polyisoprene) is widely employed in the fabrication of tires, construction industries, and biomedical applications. NR possesses unique properties due to its low modulus and high elasticity and can rapidly recover its original state upon release of external stress [18].

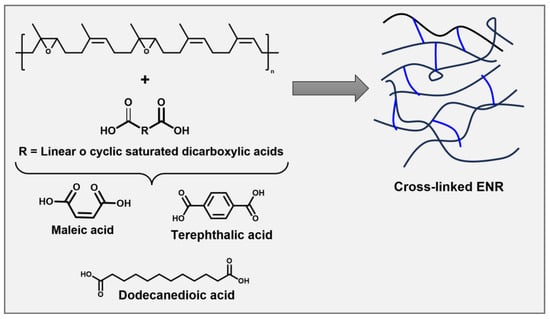

Based on reprocessability, bio-based NR can introduce bio-based chemically crosslinked thermoplastics. The bio-based chemically crosslinked/cross-linkable elastomers (CCEs) from NR and synthetic elastomers derived from bio-based monomers have been reported. CCEs possess better resilience and higher operating temperatures due to covalent three-dimensional (3D) networks [4][21][22][23][24]. Several dicarboxylic acids are used as green crosslinkers to react with ENR (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Crosslinked epoxidized natural rubber (ENR) with dicarboxylic acid.

Srirachya et al. investigated a crosslinking agent for ENR. They demonstrated that it was possible to crosslink ENR with maleic anhydride thermally; no additional catalysts were needed [21]. Riyajan et al. studied the influence on the physical properties, including the swelling behavior, tensile strength, and thermal stability of the vulcanization of ENR latex using a terephthalic acid crosslinker. It was observed that the ENR crosslinked with terephthalic acid depolymerized in natural soil compared to natural rubber vulcanized with sulfur [22]. Pire et al. crosslinked the epoxidized NR by dodecanedioic acid with 1,2-dimethylimidazole. The authors explain that 1,2-Dimethylimidazole accelerates crosslinking, and imidazolium dicarboxylate species are formed to reach the less substituted side of the epoxy site [23][24]. Generally, the ENR crosslinked with dicarboxylic acids improves mechanical properties compared to those vulcanized by sulfur because carbon–oxygen crosslinks possess higher bond energies than sulfur ones [25].

Bio-Based Elastomers with Essential Oils

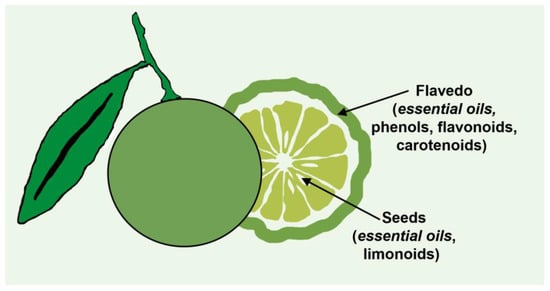

Citric fruits (Rutaceae family) are the most commonly cultivated and consumed fruits worldwide. According to the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO), global overall citrus fruit production in 2020 was around 158.49 million metric tons [26]. The major citrus-producing countries include China, Brazil, and the United States of America. Approximately 40–60% of the fruit is discarded as waste upon consumption. In general, the industrial production of citrus fruits generates 110–120 million tons of citrus waste yearly, such as peels (flavedo and albedo), seeds, and pomace [27][28][29]. It is possible to extract limonoids, essential oils, phenols, flavonoids, carotenoids, and cellulose from these wastes. Significantly, essential oils can be obtained from the peels and seeds of citrus fruit waste, and they are considered potent bio-resource materials for various uses in the food and non-food sectors. Also, these substances are considered plant-based natural products consisting of volatile and aromatic compounds present at low concentrations. Essential oils are compounds made up of isoprene units attached to 10-carbon and 15-carbon structures known as monoterpenoids and sesquiterpenoids, respectively. These compounds are typically found in the oil sacs of citrus peels and cuticles, as shown in Figure 2 [29].

Figure 2. Essential oils in the citrus peels and cuticle of the citrus fruit.

Essential oils or citrus oils have the characteristics of being low in toxicity, inexpensive, and can be obtained by several extraction techniques such as steam distillation and solvent extraction [30][31]. They are mainly used in the pharmaceutical industry to obtain active ingredients, the cosmetics industry in perfume production, food for flavoring preparation, and the chemical industry in packaging materials production, among others. In the bio-based elastomers elaboration, essential oils have significantly modified natural rubber and some industrial elastomers.

Terpenes have emerged as viable candidates to serve as monomers in bio-based elastomer production. The most common type of bio-based elastomers from terpene is β-Myrcene, which is extracted by hops, bay, and thyme oils or can be obtained by pyrolysis from β-pinene [32]. β-Myrcene has two conjugated double bonds in its structure and can be polymerized similarly to its isoprene via anionic, free-radical, coordination, and cationic reactions. These polymerization reactions can have several possibilities for 1,2-; 3,4-; and 1,4-cis or trans myrcene isomerization to obtain elastomers with similar mechanical and thermal properties to NR (Hevea brasiliensis, Palaquium gutta, and Manilkara zapota trees). In 1960, Marvel studied the polymerization of myrcene by Ziegler-type catalysts (triisobutylaluminum, TiCl4, and vanadium trichloride) with a predominantly 1,4 arrangement of the diene unit in the polymer chain, with conversions of 80% of the polymyrcene [33].

It has been reported the stereoselective polymerization of β-myrcene and β-ocimene and their copolymerization with styrene using homogeneous titanium catalysts activated by MAO (methylaluminoxane) showing different stereoselectivity, for example, 1,4-trans-poly myrcene (92%) and its copolymerization with styrene using dichloro{1,4-dithiabutanediyl-2,2′-bis(4,6-di-tert-butyl-phenyl)}titanium complex, and 1,4-cis-poly myrcene (92%) in the presence of Ti(η5-C5H5)-(η2-2,2′-methylene bis(6-tert-butyl-4-methylphenoxo))Cl complexes were obtained. Also, these catalysts were used in the β-ocimene polymerization. Other terpenes are ocimene (which can be produced from the thermal cracking of β-pinene) and farnesene (which can be found in nature like α- and β-isomers); however, farnesene can be obtained through the fermentation of sugar feedstocks [34]. When using the last catalysts with ocimene and a high temperature (70 °C), the 1,4-trans polymer (70%) is formed, while at a lower temperature, an isotactic poly-1,2-ocimene (>99%) was obtained [35].

On the other hand, Lamparelli et al. have reported that the soluble heterocomplexes consisting of sodium hydride in combination with trialkylaluminium derivatives have been used as anionic initiating in the polymerization of myrcene and its copolymerization with styrene and isoprene [36][37].

It is well known that NR and industrial elastomers such as polybutadiene (PB) and poly(styrene-butadiene-styrene) (SBS) are materials used in the production of tires, adhesives, and rubber bands, among others. The properties of elastomers are amorphous polymers found above their glass transition (Tg), which explains their deformability. Authors have demonstrated that modified elastomers such as NR are proposed to expand the application [38]. It has been reported that d-limonene, β-pinene terpenes, some menthol, β-citronellol, and citral terpenoids, mainly extracted from turpentine, lemon, mandarin, orange, mint, citronella oils, citral, and other terpenes, contain in their structure carbon–carbon double bonds, and they are used in the natural rubber modification via metathesis reactions [39][40][41][42].

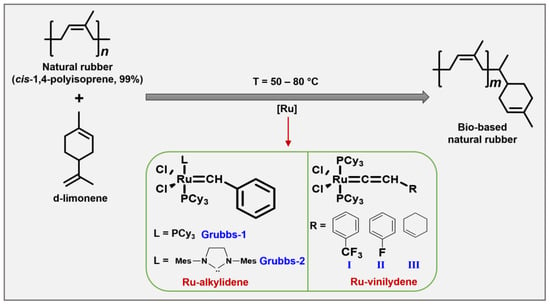

Some reports have shown that d-limonene, considered the most abundant component in mandarin (74%), lemon (87%), and orange (97%) essential oils, is used as a chain transfer agent (CTA) in the cross-metathesis reaction of NR in the presence of ruthenium carbene-alkylidene and vinylidene complex catalysts (Figure 3). These two classes of catalysts tolerate a wide range of functional groups (e.g., amino, carboxyl, acetoxy, ester, hydroxy, fluorine, and chlorine), and they are active with more sterically hindered substrates such as natural rubber [43][44][45].

Figure 3. Synthesis of bio-based NR with d-limonene via cross-metathesis.

NR modification with limonene and mandarin oils via cross-metathesis allows the synthesis of mono-terminated or terpene-terminated oligomers (Table 1) with low molecular weight around Mn × 102 g × mol−1 and yields of 80% when the catalyst Grubbs-2 is used (entries 1 and 3). In contrast, with Grubbs-1 and vinylidene-II and -III catalysts [40], the molecular weights of terpene-terminated oligomers are around Mn × 104 g × mol−1 with yields ranging from 70–96% (entries 2, 7, and 8).

Table 1. Examples of terpene-terminated oligomers (bio-based elastomers) obtained by cross-metathesis reaction of NR and SBS with d-limonene and essential oils using Ru-carbene complexes.

| Entry | Elastomer | CTA | Catalyst | [NR] b /[CTA] |

Temp. (°C) |

Yield c % |

Molecular Weight | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mn d (1H-NMR) |

Mn e (GPC) |

||||||||

| 1 | Natural rubber a | d-limonene | Grubbs-2 | 1:1 | 50 | 80 | 722 | 779 | [39] |

| 2 | Mandarin oil | Grubbs-1 | 1:1 | 100 | 74 | 16,836 | 17,554 | ||

| 3 | Mandarin oil | Grubbs-2 | 1:1 | 50 | 80 | 836 | 811 | ||

| 4 | 5:1 | 50 | 95 | 3184 | 4745 | ||||

| 5 | 10:1 | 50 | 92 | 5675 | 7281 | ||||

| 6 | Mandarin oil | I | 1:1 | 80 | 95 | 9488 | 9800 | [41] | |

| 7 | Mandarin oil | II | 1:1 | 80 | 95 | 10,941 | 10,398 | [40] | |

| 8 | Mandarin oil | III | 1:1 | 80 | 96 | 10,693 | 10,700 | [41] | |

| 9 | Poly(styrene-co-butadiene) (SBS, 30% styrene) | d-limonene | I | 1:1 | 80 | 96 | 289 | 295 | |

| 10 | Orange | I | 1:1 | 80 | 92 | 297 | 307 | ||

| 11 | Orange | Grubbs-1 | 1:1 | 50 | 93 | 285 | 325 | [40] | |

a Hevea brasiliensis natural rubber, Mn = 1.7 × 106; molar ratio [C=C]/catalyst = 250, reaction time = 24 h. b Molar ratio of NR to CTA; chain transfer agent (essential oil). c Isolated yield of products. d Mn determined by 1H-NMR end groups analysis, where one unit of d-limonene is attached to the end-group of the isoprene oligomeric chain. e Number-average (Mn) molecular weights were calculated by gel permeation chromatography (GPC). The low molecular weights were calculated by SEC.

It essential to note that Ru-vinylidene catalysts (I) showed higher catalytic efficiency in the cross-metathesis reaction of NR with d-limonene and mandarin oil to give terpene-terminated oligomers with Mn × 103 g × mol−1 (entry 6) [41] Also, authors reported that cross-metathesis reaction can control the molecular weight by the NR/CTA molar ratio (entries 3–5). A similar approach, bio-based NR, was obtained using lemon, orange, and β-pinene terpene as CTAs [39][40][41][46]. This easily accessible class of Ru complexes showed high thermal stability combined with good activity in the NR cross-metathesis.

Theoretical studies have shown that trisubstituted internal olefin (NR, d-limonene) is more difficult to break the C=C bond than one disubstituted unsaturation of the cis-polybutadiene and other polyalkenamers due to the steric hindrance of the methyl group of the NR, which makes difficult the coordination between the M=C complex and C=C double bond of isoprene [47]. For example, this has been confirmed by experimental studies in the cross-metathesis of SBS synthetic elastomer using d-limonene and orange oil as CTA. The SBS-terpene elastomer modification in the presence of ruthenium–vinylidene catalysts (I) and Grubbs-1 to several molar ratios [rubber]/[CTA] was accomplished.

3. Bio-Based Polyurethane Elastomers

The global production of polyurethane (PU) remains between 5.3 and 5.5% compared to conventional plastics such as PET, PE, PP, PVC, and PS [1][2][8]. PU has gained much attention due to its excellent thermal, mechanical, and chemical properties, diversity in material types, and their applications. There are different types of polyurethanes, including thermoplastic polyurethanes (TPUs), thermostable polyurethanes, and elastomeric polyurethanes (EPUs). The most common thermostable polyurethanes are foams, widely used as thermal insulators; among the most common EPUs are those used as adhesives, high-performance sealants, shoe soles, paints, textile fibers, gaskets, and in the construction, furniture, medical, and automotive industries. The characteristic properties of elastomeric PU include high resistance to wear and abrasion, good cushioning capacity, good flexibility at low temperatures, high resistance to fats, oils, oxygen, and ozone, excellent elastic recovery, transparency, and adhesion [48][49][50][51].

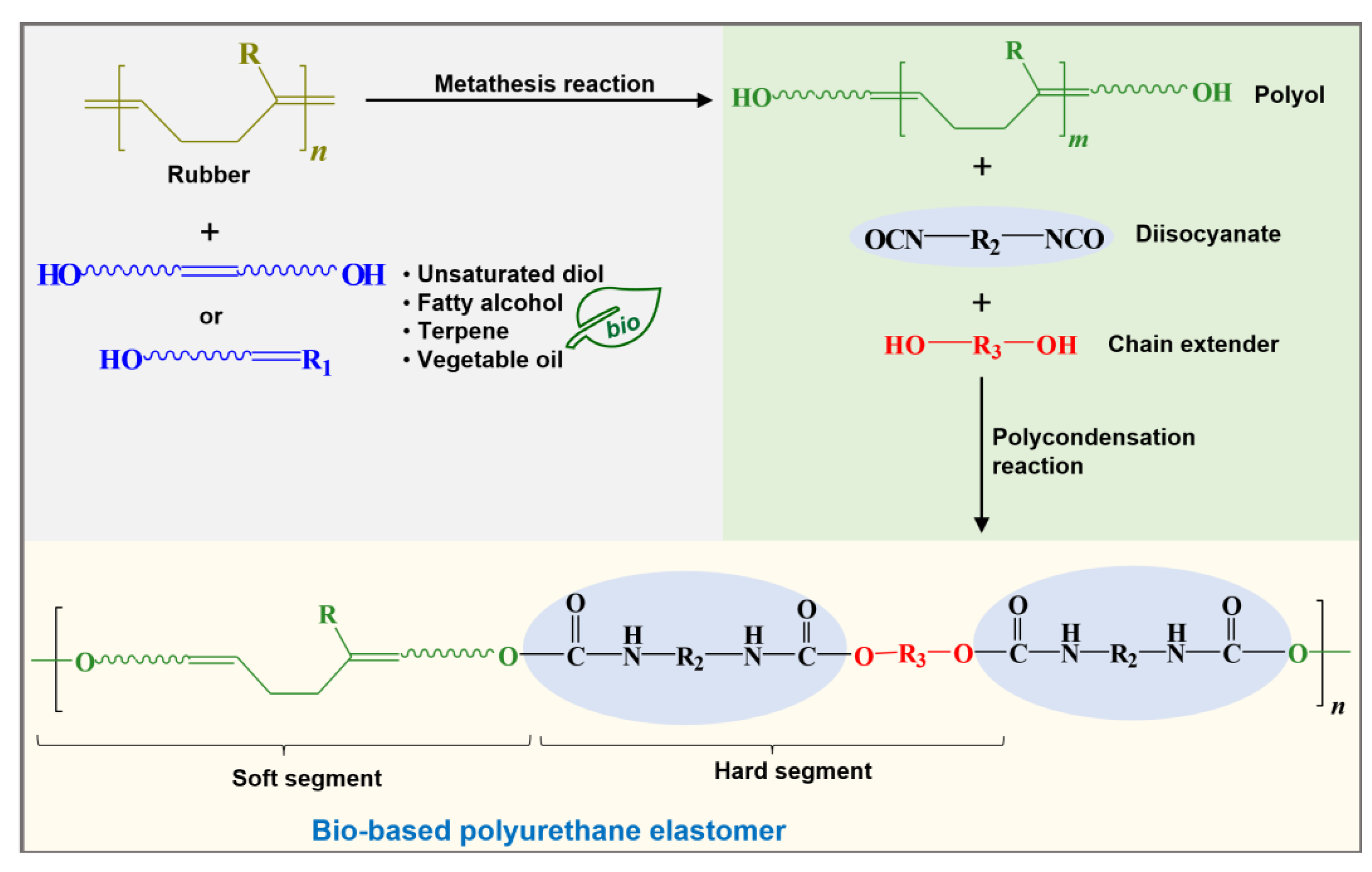

PU is synthesized by a polycondensation reaction between a diisocyanate and polyol or macrodiol with an average molecular weight in the range from 600 to 4000 g/mol, using a short-chain diol or chain extender with molecular weights in the range of 62 to 400 g/mol to increase the chain’s molecular weight and define the material’s rigidity. The polyol forms the soft and flexible segments and provides an elastomeric matrix responsible for most of the elastic properties of EPU. The diisocyanate, polyol, and diol are used at different molar ratios, and the reaction mixture will define the soft and hard segments, the type of PU, its properties, and its applications [49][52][53][54].

These three components or raw materials for the production of PU are derived from oil resources. Currently, PU is a non-recyclable polymer that comes from non-renewable sources. It can also be a thermoplastic PU, which makes it a complex material to recycle and reuse; moreover, there is no adequate waste management. It takes hundreds to thousands of years to decompose or biodegrade, contributing to plastic waste accumulation, nano and microplastic formation, and environmental pollution [55][56]. Due to this, the synthesis of PU from natural and renewable resources has attracted the attention of researchers and industries to form different types of bio-based PU [51][57][58][59]. Precisely for this study, bio-based EPU shares elastic properties like rubbers and thermoplastic polyurethane; these properties are provided mainly by the polyol from natural resources, making it ideal for different applications.

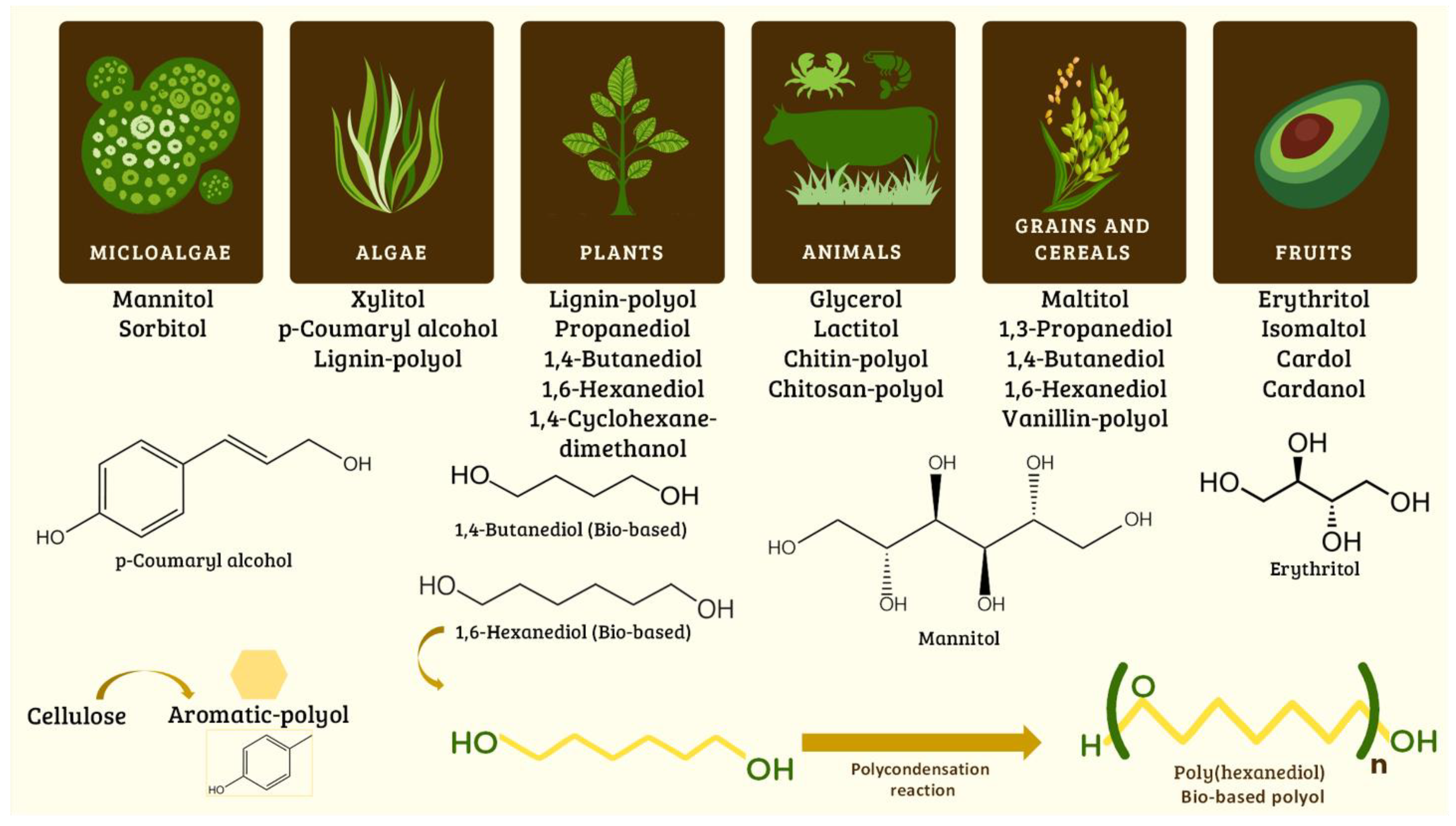

Different diols and polyols have been used to synthesize bio-based EPUs derived from algae, plants, animals, crustaceans, grains, cereals, and fruits. Some diols and polyols are mannitol, sorbitol, xylitol, glycerol, cardol, 1,3-propanediol, 1,4-butanediol, and 1,6-hexanediol bio-based (Figure 4). Many polyols have been obtained and modified from lignin, chitin, chitosan, and cellulose (aromatic polyol) [60][61][62][63][64][65][66]. Some diols can be converted into polyols by a polycondensation reaction; for example, polyhexanediol (bio-based polyol) has been obtained from 1,6-hexanediol [62].

Figure 4. Synthesis of bio-based diols and polyols from natural and renewable resources used to synthesize polyurethanes.

Various polyols have been synthesized from industrial and natural rubbers, which have elastomeric properties because they come from rubbers, such as excellent elastic recovery, low transition temperature (Tg), and flexibility at low temperatures, which will be transmitted to the polyurethane. Polyols from polybutadiene (PB), polybutadiene rubber (BR), or SBS copolymer have been synthesized. BR has repeating butadiene units, which can be trans or cis-1,4-polybutadiene and are modified with another compound or reagent with hydroxyl (-OH)-terminated groups, which are called “hydroxy-terminated polybutadiene” (HTPB), hydroxy telechelic polybutadiene or polyols; these have been obtained by different methods such as oxidation or oxidolysis [67][68], anionic polymerization [69], via copolymerization [70], via nickel catalyst [71], and by olefin metathesis [72][73]. Other polyols have been obtained from natural rubber (NR), NR comes from the rubber tree, or from its synthetic form, polyisoprene rubber (IR), which has repeating isoprene units and can be trans or cis-1,4-polyisoprene [18]. In the same way, NR is modified with another compound with -OH groups, which are called “hydroxy-terminated polyisoprene” (HTPI or HTNR) or polyols; these have been obtained by different methods such as epoxidation [74][75], anionic polymerization [76], and by olefin metathesis [42].

Of the mentioned methods, obtaining polyols by olefin metathesis reaction has shown that both natural and industrial rubbers can be modified or degraded under mild conditions, at low temperatures and atmospheric pressure, in solvent-free conditions, or allowing the use of green solvents, and using fatty alcohol, terpenes, diols, or essential oils with OH groups from natural resources such as chain transfer agent CTA for the synthesis and production of bio-based elastomeric polyurethanes (Figure 5). This is a new and promising synthesis route to produce bio-based polyols for applications in engineering polymers and elastomeric materials.

Figure 5. Synthesis of bio-based polyurethane elastomer from polyols obtained by industrial or natural rubbers degradation (providing the elastomeric part) and essential oils or fatty alcohols derived from natural resources. R is for rubber repetitive unit (R = H for PB, BR; R = CH3 for PI, IR, NR). R1 is for vegetable oil, unsatured diol, fatty alcohol, or terpene (e.g., 9-decen-1-ol, 10-undecen-1-ol, castor oil (Ricinus communis), citronellol, geraniol, myrcenol, eugenol). R2 is for aromatic or aliphatic structures for diisocyanates (e.g., MDI, TDI, IPDI, HDI). R3 is for C2–C6 chain extender length (e.g., ethanediol, propanediol, butanediol, hexanediol).

References

- Plastics Europe AISBL Plastics-the Facts 2022. Available online: https://plasticseurope.org/knowledge-hub/plastics-the-facts-2022/ (accessed on 17 November 2023).

- Plastics Europe AISBL Plastics-the Fast Facts 2023. Available online: https://plasticseurope.org/knowledge-hub/plastics-the-fast-facts-2023/ (accessed on 28 November 2023).

- Aiswarya, S.; Awasthi, P.; Banerjee, S.S. Self-Healing Thermoplastic Elastomeric Materials: Challenges, Opportunities and New Approaches. Eur. Polym. J. 2022, 181, 111658.

- Tang, S.; Li, J.; Wang, R.; Zhang, J.; Lu, Y.; Hu, G.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, L. Current Trends in Bio-based Elastomer Materials. SusMat 2022, 2, 2–33.

- Chen, S.; Wu, Z.; Chu, C.; Ni, Y.; Neisiany, R.E.; You, Z. Biodegradable Elastomers and Gels for Elastic Electronics. Adv. Sci. 2022, 9, 2105146.

- Vert, M.; Doi, Y.; Hellwich, K.; Hess, M.; Hodge, P.; Kubisa, P.; Rinaudo, M.; Schué, F. Terminology for Biorelated Polymers and Applications (IUPAC Recommendations 2012). Chem. Int.-Newsmag. IUPAC 2012, 84, 377–410.

- Vanderreydt, I.; Rommens, T.; Tenhunen, A.; Mortensen, L.F. European Topic Centre Waste and Materials in a Green Economy; European Environment Agency: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2021; pp. 1–68.

- Burelo, M.; Hernández-Varela, J.D.; Medina, D.I.; Treviño-Quintanilla, C.D. Recent Developments in Bio-Based Polyethylene: Degradation Studies, Waste Management and Recycling. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21374.

- Rosenboom, J.G.; Langer, R.; Traverso, G. Bioplastics for a Circular Economy. Nat. Rev. Mater. 2022, 7, 117–137.

- Lei, W.; Zhou, X.; Russell, T.P.; Hua, K.C.; Yang, X.; Qiao, H.; Wang, W.; Li, F.; Wang, R.; Zhang, L. High Performance Bio-Based Elastomers: Energy Efficient and Sustainable Materials for Tires. J. Mater. Chem. A Mater. 2016, 4, 13058–13062.

- Mülhaupt, R. Green Polymer Chemistry and Bio-Based Plastics: Dreams and Reality. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2013, 214, 159–174.

- Morschbacker, A. Bio-Ethanol Based Ethylene. Polym. Rev. 2009, 49, 79–84.

- McAloon, A.; Taylor, F.; Yee, W.; Regional, E.; Ibsen, K.; Wooley, R.; Biotechnology, N. Determining the Cost of Producing Ethanol from Corn Starch and Lignocellulosic Feedstocks; National Renewable Energy Laboratory: Golden, CO, USA, 2000; Volume 44.

- Ferreira-Leitao, V.; Gottschalk, L.M.F.; Ferrara, M.A.; Nepomuceno, A.L.; Molinari, H.B.C.; Bon, E.P.S. Biomass Residues in Brazil: Availability and Potential Uses. Waste Biomass Valorization 2010, 1, 65–76.

- Zhang, X.; Niu, K.; Song, W.; Yan, S.; Zhao, X.; Lu, Y.; Zhang, L. The Effect of Epoxidation on Strain-Induced Crystallization of Epoxidized Natural Rubber. Macromol. Rapid Commun. 2019, 40, 1–5.

- Heng, T.S.; Joo, G.K. Rubber. Encycl. Appl. Plant Sci. 2016, 3, 402–409.

- Barlow, F.W. Rubber, Gutta, and Chicle. In Natural Products of Woody Plants: Chemicals Extraneous to the Lignocellulosic Cell Wall; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1989; pp. 1028–1050.

- Cruz-Morales, J.A.; Gutiérrez-Flores, C.; Zárate-Saldaña, D.; Burelo, M.; García-Ortega, H.; Gutiérrez, S. Synthetic Polyisoprene Rubber as a Mimic of Natural Rubber: Recent Advances on Synthesis, Nanocomposites, and Applications. Polymers 2023, 15, 4074.

- Darvell, B.W. More Polymers. In Materials Science for Dentistry; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 699–718.

- Reyes-Gómez, S.; Montiel, R.; Tlenkopatchev, M.A. Chicle Gum from Sapodilla (Manilkara zapota) as a Renewable Resource for Metathesis Transformation. J. Mex. Chem. Soc. 2018, 61, 1–15.

- Srirachya, N.; Kobayashi, T.; Boonkerd, K. An Alternative Crosslinking of Epoxidized Natural Rubber with Maleic Anhydride. Key Eng. Mater. 2017, 748, 84–90.

- Riyajan, S.A.; Khiatdet, W.; Leejarkpai, T.; Riyapan, D. Crosslinking of Epoxidized Natural Rubber with Terephthalic Acid: Effect of Terephthalic Acid and Cassava Starch. J. Polym. Mater. 2014, 31, 145–158.

- Pire, M.; Lorthioir, C.; Oikonomou, E.K.; Norvez, S.; Iliopoulos, I.; Le Rossignol, B.; Leibler, L. Imidazole-Accelerated Crosslinking of Epoxidized Natural Rubber by Dicarboxylic Acids: A Mechanistic Investigation Using NMR Spectroscopy. Polym. Chem. 2012, 3, 946–953.

- Pire, M.; Oikonomou, E.K.; Imbernon, L.; Lorthioir, C.; Iliopoulos, I.; Norvez, S. Crosslinking of Epoxidized Natural Rubber by Dicarboxylic Acids: An Alternative to Standard Vulcanization. Macromol. Symp. 2013, 331–332, 89–96.

- Pire, M.; Norvez, S.; Iliopoulos, I.; Le Rossignol, B.; Leibler, L. Epoxidized Natural Rubber/Dicarboxylic Acid Self-Vulcanized Blends. Polymer 2010, 51, 5903–5909.

- Smilanick, J.L.; Erasmus, A.; Palou, L. Citrus Fruits. Fresh and Processed; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021.

- Sharma, K.; Mahato, N.; Cho, M.H.; Lee, Y.R. Converting Citrus Wastes into Value-Added Products: Economic and Environmently Friendly Approaches. Nutrition 2017, 34, 29–46.

- Anticona, M.; Blesa, J.; Frigola, A.; Esteve, M.J. High Biological Value Compounds Extraction from Citruswaste with Non-Conventional Methods. Foods 2020, 9, 811.

- Suri, S.; Singh, A.; Nema, P.K. Current Applications of Citrus Fruit Processing Waste: A Scientific Outlook. Appl. Food Res. 2022, 2, 100050.

- Stratakos, A.C.; Koidis, A. Methods for Extracting Essential Oils. In Essential Oils in Food Preservation, Flavor and Safety; Preedy, V.R., Ed.; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016; pp. 31–38. ISBN 9780124166417.

- León, C.; Jordán, E.P.; Salazar, K.; Castellanos, E.X.; Salazar, F.W. Extraction System for the Industrial Use of Essential Oil of the Subtle Lemon (Citrus aurantifolia). J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2020, 1432, 012044.

- Behr, A.; Toepell, S. Comparison of Reactivity in the Cross Metathesis of Allyl Acetate-Derivatives with Oleochemical Compounds. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 2015, 92, 603–611.

- Marvel, C.S.; HWA, C.C.L. Polymyrcene. J. Polym. Sci. 1960, 45, 25–34.

- Benjamin, K.R.; Silva, I.R.; Cherubim, J.P.; McPhee, D.; Paddon, C.J. Developing Commercial Production of Semi-Synthetic Artemisinin, and of β-Farnesene, an Isoprenoid Produced by Fermentation of Brazilian Sugar. J. Braz. Chem. Soc. 2016, 27, 1339–1345.

- Naddeo, M.; Buonerba, A.; Luciano, E.; Grassi, A.; Proto, A.; Capacchione, C. Stereoselective Polymerization of Biosourced Terpenes β-Myrcene and β-Ocimene and Their Copolymerization with Styrene Promoted by Titanium Catalysts. Polymer 2017, 131, 151–159.

- Lamparelli, D.H.; Kleybolte, M.M.; Winnacker, M.; Capacchione, C. Sustainable Myrcene-based Elastomers via a Convenient Anionic Polymerization. Polymers 2021, 13, 838.

- Lamparelli, D.H.; Winnacker, M.; Capacchione, C. Stereoregular Polymerization of Acyclic Terpenes. Chempluschem 2022, 87, e202100366.

- Pineda-Contreras, A.; Vargas, J.; Santiago, A.A.; Martínez, A.; Cruz-Morales, J.A.; Reyes-Gómez, S.; Burelo, M.; Gutiérrez, S. Metátesis de Olefinas En México: Desarrollo y Aplicaciones En Nuevos Materiales Poliméricos y En Química Sustentable. Mater. Av. 2018, 29, 65–81.

- Martínez, A.; Tlenkopatchev, M.A. Metathesis Transformations of Natural Products: Cross-Metathesis of Natural Rubber and Mandarin Oil by Ru-Alkylidene Catalysts. Molecules 2012, 17, 6001.

- Martínez, A.; Clark-Tapia, R.; Tlenkopatchev, M. Synthesis and Characterization of New Ruthenium Vinylidene Complexes. Lett. Org. Chem. 2014, 11, 748–754.

- Martínez, A.; Zuniga-Villarreal, N.; Tlenkopatchev, A.M. New Ru-Vinylidene Catalysts in the Cross-Metathesis of Natural Rubber and Poly(Styrene-Co-Butadiene) with Essential Oils. Curr. Org. Synth. 2016, 13, 876–882.

- Burelo, M.; Martínez, A.; Cruz-Morales, J.A.; Tlenkopatchev, M.A.; Gutiérrez, S. Metathesis Reaction from Bio-Based Resources: Synthesis of Diols and Macrodiols Using Fatty Alcohols, β-Citronellol and Natural Rubber. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2019, 166, 202–212.

- Li, H.; Caire da Silva, L.; Schulz, M.D.; Rojas, G.; Wagener, K.B. A Review of How to Do an Acyclic Diene Metathesis Reaction. Polym. Int. 2017, 66, 7–12.

- Tlenkopatchev, M.A.; Barcenas, A.; Fomine, S. Computational Study of Metathesis Degradation of Rubber, 1. Distribution of Cyclic Oligomers via Intramolecular Metathesis Degradation of Cis -Polybutadiene. Macromol. Theory Simul. 1999, 8, 581–585.

- Gutierras, S.; Vargas, S.M.; Tlenkopatchev, M.A. Computational Study of Metathesis Degradation of Rubber. Distributions of Products for the Ethenolysis of 1,4-Polyisoprene. Polym. Degrad. Stab. 2004, 83, 149–156.

- Martínez, A.; Tlenkopatchev, M.A. Citrus Oils as Chain Transfer Agents in the Cross-Metathesis Degradation of Polybutadiene in Block Copolymers Using Ru-Alkylidene Catalysts. Nat. Sci. 2013, 05, 857–864.

- Korshak, Y.V.; Tlenkopatchev, M.A.; Dolgoplosk, B.A.; Avdexina, E.G.; Kutepov, D.F. Intra- and Intermolecular Metathesis Reactions in the Formation and Degradation of Unsaturated Polymers. J. Mol. Catal. 1982, 15, 207–218.

- McKeen, L.W. Elastomers and Rubbers. In Film Properties of Plastics and Elastomers; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017; Volume 13, pp. 419–448.

- Drobny, J.G. Thermoplastic Polyurethane Elastomers. In Handbook of Thermoplastic Elastomers; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; Volume 9, pp. 233–253.

- Agnol, L.D.; Toso, G.T.; Dias, F.T.G.; Soares, M.R.F.; Bianchi, O. Thermoplastic Polyurethane/Butylene-Styrene Triblock Copolymer Blends: An Alternative to Tune Wear Behavior. Polym. Bull. 2022, 79, 5199–5217.

- Hernández-Zea, N.; Gaytán, I.; Burelo, M. Poliuretanos Sintéticos y Biobasados: Síntesis, Producción, Reciclaje y Métodos de Degradación. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, Mexico City, Mexico, 2023; pp. 64–80.

- Ornaghi, H.L.; Nohales, A.; Asensio, M.; Gómez, C.M.; Bianchi, O. Effect of Chain Extenders on the Thermal and Thermodegradation Behavior of Carbonatodiol Thermoplastic Polyurethane. Polym. Bull. 2023, 1–20.

- Touchet, T.J.; Cosgriff-Hernandez, E.M. Hierarchal Structure-Property Relationships of Segmented Polyurethanes. In Advances in Polyurethane Biomaterials; Elsevier Inc.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016; Volume 1, pp. 3–22. ISBN 9780081006221.

- Kasprzyk, P.; Głowińska, E.; Parcheta-Szwindowska, P.; Rohde, K.; Datta, J. Green TPUs from Prepolymer Mixtures Designed by Controlling the Chemical Structure of Flexible Segments. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7438.

- Burelo, M.; Gaytán, I.; Loza-Tavera, H.; Cruz-Morales, J.A.; Zárate-Saldaña, D.; Cruz-Gómez, M.J.; Gutiérrez, S. Synthesis, Characterization and Biodegradation Studies of Polyurethanes: Effect of Unsaturation on Biodegradability. Chemosphere 2022, 307, 136136.

- Sánchez-Reyes, A.; Gaytán, I.; Pulido-García, J.; Burelo, M.; Vargas-Suárez, M.; Cruz-Gómez, M.J.; Loza-Tavera, H. Genetic Basis for the Biodegradation of a Polyether-Polyurethane-Acrylic Copolymer by a Landfill Microbial Community Inferred by Metagenomic Deconvolution Analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2023, 881, 163367.

- Scheelje, F.C.M.; Meier, M.A.R. Non-Isocyanate Polyurethanes Synthesized from Terpenes Using Thiourea Organocatalysis and Thiol-Ene-Chemistry. Commun. Chem. 2023, 6, 239.

- Burelo, M.; Jiménez Olivares, A.; Tlenkopatchev, M.A.; Gutiérrez, S. Síntesis y Caracterización de Poliuretanos Biodegradables. Rev. Tend. Docencia Investig. Química 2018, 4, 546–552.

- Contreras, J.; Valdés, O.; Mirabal-Gallardo, Y.; de la Torre, A.F.; Navarrete, J.; Lisperguer, J.; Durán-Lara, E.F.; Santos, L.S.; Nachtigall, F.M.; Cabrera-Barjas, G.; et al. Development of Eco-Friendly Polyurethane Foams Based on Lesquerella Fendleri (A. Grey) Oil-Based Polyol. Eur. Polym. J. 2020, 128, 109606.

- Cronjé, Y.; Farzad, S.; Mandegari, M.; Görgens, J.F. A Critical Review of Multiple Alternative Pathways for the Production of a High-Value Bioproduct from Sugarcane Mill Byproducts: The Case of Adipic Acid. Biofuel Res. J. 2023, 10, 1933–1947.

- Beerthuis, R.; Rothenberg, G.; Shiju, N.R. Catalytic Routes towards Acrylic Acid, Adipic Acid and ε-Caprolactam Starting from Biorenewables. Green Chem. 2015, 17, 1341–1361.

- Sardon, H.; Mecerreyes, D.; Basterretxea, A.; Avérous, L.; Jehanno, C. From Lab to Market: Current Strategies for the Production of Biobased Polyols. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 10664–10677.

- Laurichesse, S.; Huillet, C.; Avérous, L. Original Polyols Based on Organosolv Lignin and Fatty Acids: New Bio-Based Building Blocks for Segmented Polyurethane Synthesis. Green Chem. 2014, 16, 3958–3970.

- Guo, X.; Wang, J.; Chen, L.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Fang, L. Liquefied Chitin-Derived Super Tough, Sustainable, and Anti-Bacterial Polyurethane Elastomers. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 465, 143074.

- Huang, J.; Wang, H.; Liu, W.; Huang, J.; Yang, D.; Qiu, X.; Zhao, L.; Hu, F.; Feng, Y. Solvent-Free Synthesis of High-Performance Polyurethane Elastomer Based on Low-Molecular-Weight Alkali Lignin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 225, 1505–1516.

- Gang, H.; Lee, D.; Choi, K.Y.; Kim, H.N.; Ryu, H.; Lee, D.S.; Kim, B.G. Development of High Performance Polyurethane Elastomers Using Vanillin-Based Green Polyol Chain Extender Originating from Lignocellulosic Biomass. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2017, 5, 4582–4588.

- Zhang, P.; Tan, W.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Yuan, J.; Deng, J. Chemical Modification of Hydroxyl-Terminated Polybutadiene and Its Application in Composite Propellants. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2021, 60, 3819–3829.

- Zhou, Q.; Jie, S.; Li, B.G. Preparation of Hydroxyl-Terminated Polybutadiene with High Cis-1,4 Content. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2014, 53, 17884–17893.

- Chen, J.M.; Lu, Z.J.; Pan, G.Q.; Qi, Y.X.; Yi, J.J.; Bai, H.J. Synthesis of Hydroxyl-Terminated Polybutadiene Possessing High Content of 1,4-Units via Anionic Polymerization. Chin. J. Polym. Sci. 2010, 28, 715–720.

- Zhang, Q.; Shu, Y.; Liu, N.; Lu, X.; Shu, Y.; Wang, X.; Mo, H.; Xu, M. Hydroxyl Terminated Polybutadiene: Chemical Modification and Application of These Modifiers in Propellants and Explosives. Cent. Eur. J. Energetic Mater. 2019, 16, 153–193.

- Min, X.; Fan, X. A New Strategy for the Synthesis of Hydroxyl Terminated Polystyrene-b-Polybutadiene-b-Polystyrene Triblock Copolymer with High Cis-1, 4 Content. Polymers 2019, 11, 598.

- Bielawski, C.W.; Scherman, O.A.; Grubbs, R.H. Highly Efficient Syntheses of Acetoxy-and Hydroxy-Terminated Telechelic Poly(Butadiene)s Using Ruthenium Catalysts Containing N-Heterocyclic Ligands. Polymer 2001, 42, 4939–4945.

- Burelo, M.; Gutiérrez, S.; Treviño-Quintanilla, C.D.; Cruz-Morales, J.A.; Martínez, A.; López-Morales, S. Synthesis of Biobased Hydroxyl-Terminated Oligomers by Metathesis Degradation of Industrial Rubbers SBS and PB: Tailor-Made Unsaturated Diols and Polyols. Polymers 2022, 14, 4973.

- Sukhawipat, N.; Saetung, N.; Pilard, J.F.; Bistac, S.; Saetung, A. Synthesis and Characterization of Novel Natural Rubber Based Cationic Waterborne Polyurethane: Effect of Emulsifier and Diol Class Chain Extender. J. Appl. Polym. Sci. 2018, 135, 45715.

- Tsupphayakorn-aek, P.; Suwan, A.; Tulyapitak, T.; Saetung, N.; Saetung, A. A Novel UV-Curable Waterborne Polyurethane-Acrylate Coating Based on Green Polyol from Hydroxyl Telechelic Natural Rubber. Prog. Org. Coat. 2022, 163, 106585.

- Qiang-Qiang, S.; Zai-Jun, L.; Lin, Z.; Kai, D.; Xuan, L. Synthesis of Hydroxyl-Terminated Polyisoprene Telechelic Polymers with High Content of 1,4-Structures. Acta Chim. Sin. 2008, 66, 117–120.

More

Information

Subjects:

Polymer Science

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.2K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

16 Jan 2024

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No