Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | monique johanna wilhelmina maria Johanna Wilhelmina Maria Heijmans | -- | 1880 | 2023-12-22 10:26:57 | | | |

| 2 | Jason Zhu | + 74 word(s) | 1954 | 2023-12-25 03:42:33 | | | | |

| 3 | Jason Zhu | Meta information modification | 1954 | 2023-12-29 03:54:41 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Song, Y.; Beltran Puerta, J.; Medina-Aedo, M.; Canelo-Aybar, C.; Valli, C.; Ballester, M.; Rocha, C.; Garcia, M.L.; Salas-Gama, K.; Kaloteraki, C.; et al. Self-Management Interventions for Type II Diabetes. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/53063 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Song Y, Beltran Puerta J, Medina-Aedo M, Canelo-Aybar C, Valli C, Ballester M, et al. Self-Management Interventions for Type II Diabetes. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/53063. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Song, Yang, Jessica Beltran Puerta, Melixa Medina-Aedo, Carlos Canelo-Aybar, Claudia Valli, Marta Ballester, Claudio Rocha, Montserrat León Garcia, Karla Salas-Gama, Chrysoula Kaloteraki, et al. "Self-Management Interventions for Type II Diabetes" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/53063 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Song, Y., Beltran Puerta, J., Medina-Aedo, M., Canelo-Aybar, C., Valli, C., Ballester, M., Rocha, C., Garcia, M.L., Salas-Gama, K., Kaloteraki, C., Santero, M., Niño De Guzmán, E., Spoiala, C., Gurung, P., Willemen, F., Cools, I., Bleeker, J., Poortvliet, R., Laure, T., ...Heijmans, M. (2023, December 22). Self-Management Interventions for Type II Diabetes. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/53063

Song, Yang, et al. "Self-Management Interventions for Type II Diabetes." Encyclopedia. Web. 22 December, 2023.

Copy Citation

Self-management interventions (SMIs) may be promising in the treatment of Diabetes Mellitus Type 2 (T2DM). However, accurate comparisons of their relative effectiveness are challenging, partly due to a lack of clarity and detail regarding the intervention content being evaluated.

diabetes type 2

self-management interventions

evidence mapping

1. Introduction

With the aging of populations worldwide, chronic conditions are a major concern, given their significant impact on individual patients, health care and society as a whole. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that by 2025, chronic diseases will account for 73% of all deaths and 60% of the global disease burden [1].

One chronic disease that has rapidly evolved during the last decades as a major public health problem is Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus (T2DM). The global prevalence of T2DM in adults was about 536.6 million people in 2021, and this number is expected to increase further to 783.2 million people by 2045 [2]. Diabetes is a chronic metabolic disease characterized by dysregulation of carbohydrate, lipid and protein metabolism, and results from impaired insulin secretion, insulin resistance or a combination of both. The management of T2DM often involves a combination of medical treatments and lifestyle changes geared to normalize blood sugar levels and decrease cardiovascular risk. These may include medication, diet, exercise, and regular self-monitoring activities, of which the success ultimately relies on patients’ abilities to accept and take responsibility for their disease [3]. For most patients, this self-management is a difficult task that challenges them on a daily basis and often has a considerable impact on work, family and social life [4][5].

Self-management interventions (SMIs) are developed to support people in their daily self-management tasks. Although different definitions of SMIs exist [6], in general, SMIs can be characterized as supportive interventions that healthcare staff, peers, or laypersons provide to increase patients’ skills and confidence in managing their long-term condition. Interventions to support self-management of T2DM may include, among others, education, support for self-monitoring, lifestyle advice, goal setting for behavioral change and coaching [7].

Evidence has shown that SMIs for type 2 diabetes can be effective, for example, by reducing glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) and by losing weight [8][9]. However, it remains unclear which components or approaches to self-management support contribute most to this effectiveness [6][8]. This is mainly due to the heterogeneity in study design and reporting [10]. Heterogeneity also hinders the knowledge translation from scientific evidence into clinical practice and the replication of successful SMIs by other researchers.

2. Key Characteristics of Included RCTs

The 665 studies, composing 164,437 T2DM adults with a median number of 123 adults per RCT (range 10–14,559) and a median age of 58 years old, were conducted in 64 different countries; 141 were conducted in Europe (21%), 79% outside Europe and only five studies were conducted in more than one country. Most of the studies came from the United States (35%), followed at a distance by Iraq (7%), the United Kingdom (6%), China (6%) and Korea (5%). Almost all studies were implemented on an individual patient level (92%) as compared to the population level. Almost without exceptions, studies were developed for patients (99%), with only one study for caregivers and eight targeting both patients and caregivers.

The number of intervention arms (n = 879 in total) in these 665 studies varied between two and five, but the majority of the studies (90%) included two arms. Most studies compared an SMI to usual care (n = 530, 80%), whereas 135 studies compared one or more intervention arms (head-to-head interventions). Usual care was defined as such by the authors and included regular visits and a form of education in most cases. In some studies, usual care (as indicated by the authors) consisted of something more than just information or education, for example, skills training or coaching. In this case, researchers called it ‘usual care plus’. In 20% of all intervention arms (n = 879), the intervention content or delivery methods were tailored to the characteristics of the study population (e.g., educational material of an existing intervention that was simplified because of respondents with low health literacy, translated because of Spanish speaking people, or adapted because of known gender differences between men and women).

3. Characteristics of the Participants

Across all studies, participants were more often female (mean 57%, SD 49–67%); the mean age was 58 years old, and the mean time since diagnosis was 8.6 years across studies. Although most studies used general samples of T2DM, others used more specific inclusion criteria: 72 studies (11%) focused specifically on populations with a low socio-economic status. In most of these studies, education or income was used as a proxy for inclusion; 13% of the studies targeted specific minority groups. These were mostly studies from the United States and concerned immigrants in general or more specific groups such as African Americans, Mexican Americans, Latinos or veterans. Information on health literacy levels was only provided in 29 studies (4%); 13% (n = 88) of the studies focused on diabetes patients with comorbidity; among them, 22% did not specify the type of comorbidity. In studies that did, obesity, hypertension and depression were the most common comorbidities.

Most studies described their T2DM populations with respect to sex (96%), age (97%) and diabetes control (HbA1c; 83%). Other information on study populations, such as illness duration, comorbidities, socio-economic status characteristics and health literacy levels, were described less frequently. Age (61% of trials used an age range for patients to be included) and diabetes control (41% of the studies used a threshold value for HbA1c) were most often used as specific inclusion criteria. Other characteristics, such as time since diagnosis (17%), belonging to a cultural minority group (11%), having comorbidity (9%), sex (4%), socio-economic status (4%) and health literacy levels (1%), were less often used as explicit inclusion criteria for the SMIs in diabetes.

4. Characteristics of the SMIs Reported

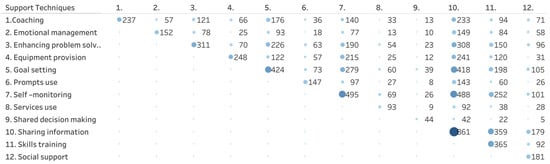

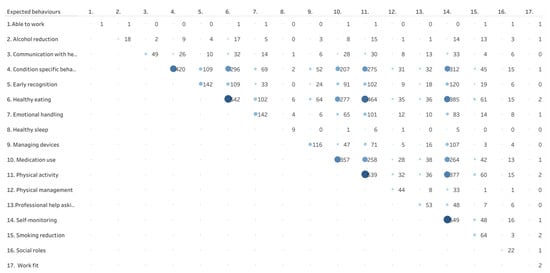

Figure 1 shows a matrix with the frequency with which specific SM support techniques are combined across studies. Figure 2 shows the number of studies in which expected behaviors go together in one study.

Figure 1. Frequency in which support techniques are combined across intervention arms (n = 879). The size and color of the bubble indicates the number of studies including each combination presented, with bigger size and darker color referring to more studies included.

Figure 2. Frequency in which expected behaviors are combined across intervention arms (n = 879). The size and color of the bubble indicates the number of studies including each combination presented, with bigger size and darker color referring to more studies included.

4.1. Self-Management Support Techniques

Self-management techniques are techniques or methods used to provide care and encouragement to people with chronic conditions and their carers to help them understand their central role in managing their condition, make informed decisions about care and engage in appropriate behaviors. In the intervention arms, the number of self-management support techniques varied between 1 and 11 (median 4, IQR 3–6). Sharing information was used in almost all intervention arms (98%), followed by self-monitoring (56%), goal setting (48%) and skills training (42%). Other techniques, for example, learning skills to handle emotions and learning to use social support or external resources, such as specific websites, were reported in less than a fifth of the studies. Shared decision-making was least mentioned as a technique to support self-management (5%). It appeared that in the 879 intervention arms, a specific combination of support techniques was frequently offered: sharing information plus self-monitoring (n = 488), sharing information plus goal setting (n = 418), sharing information plus skills training (n = 359), sharing information plus problem-solving (n = 308) and self-monitoring plus goal setting (n = 279) (Figure 1).

4.2. Expected Self-Management Behaviors

Expected self-management behaviors refer to decisions and behaviors that patients with chronic diseases are expected to engage in to improve their health. These behaviors are the focus of the self-management interventions and support techniques. In the intervention arms, the number of expected behaviors mentioned varied between 1 and 12 (median 3, IQR 2–5). Expected behaviors of T2DM patients most often included healthy eating (62%) and physical activity (61%), both being lifestyle-related behaviors; self-monitoring (63%), condition-specific behaviors like checking your feet (48%) and medication use (41 were also frequently mentioned; behaviors in relation to work and social roles, healthy sleep, alcohol or smoking reduction and communicating with health care were seldomly reported (Figure 2). Figure 2 also shows that in the 879 intervention arms, the combinations of healthy eating and physical activity (n = 474), healthy eating and self-monitoring (n = 390) and physical activity and self-monitoring (n = 380) are addressed together.

4.3. Mode of Delivery

Support delivery methods. In the intervention arms, half of the arms (53%) used support sessions; 10% used clinical visits, 11% were self-guided, and a quarter (26%) of the interventions used a combination of methods. Almost half of the interventions were conducted face-to-face; one-third of the interventions used a combination of face-to-face contacts and remote mediums, mainly phones. Two-thirds of the interventions were given to individual patients. One-third in groups (not in table).

Type of location. Most interventions took place in a single location (75%). Outpatient care (43%) and homecare (24%) were the locations mentioned most often; 16% of the interventions took place in a virtual surrounding; 15% in community settings; SMIs for diabetes were hardly given in hospitals, long-term care facilities or at the workplace.

Type of provider. In the majority of the interventions (58%), only one provider was involved in the intervention arm, most of the time being a nurse (36%), educator (29%), physician (20%) or nutritionist (18%). Peers and laypersons, psychologists or social workers were hardly involved in SMIs for T2DMs. In one-third of the intervention arms, two or more providers were involved.

5. Outcomes Reported in the Included RCTs

Table 1 shows the frequency of reported outcomes in the 665 included RCTs. Clinical outcomes were most frequently used as outcomes for the effectiveness of SMIs in T2DM, including HbA1c (83%), weight (53%), lipid profile (45%) and blood pressure management (42%). Quality of life and physical activity were reported as outcomes in 27% of the studies. Other outcomes, such as adherence to a diet or medication, were reported in less than 16% of the trials. One out of six addressed outcomes related to empowerment, such as self-efficacy (18%) or knowledge (16%). Other empowerment outcomes, such as patient activation or level of health literacy, were not used as outcome measures. The same counts for outcomes related to experiences with care and healthcare use (<5%).

Table 1. Frequency in which Core Outcomes (COS) were addressed in studies (N = 665).

| Category of Outcomes | Type | n | % |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basic empowerment | Self-efficacy | 120 | 18% |

| Knowledge | 109 | 16% | |

| Patient activation | 11 | 2% | |

| Health literacy | 3 | 0% | |

| Adherence to | Physical activity | 153 | 23% |

| Dietary habits | 106 | 16% | |

| Self-management activities in general | 111 | 17% | |

| Medication | 92 | 14% | |

| Smoking cessation | 14 | 2% | |

| Self-monitoring | 63 | 10% | |

| Clinical | HbA1c | 550 | 83% |

| Weight | 353 | 53% | |

| Lipid profile | 296 | 45% | |

| Blood pressure | 281 | 42% | |

| Hypoglycemia | 28 | 4% | |

| Hyperglycemia | 13 | 2% | |

| Complications | 15 | 2% | |

| Life expectancy | 2 | 0% | |

| Quality of life | Quality of life | 180 | 27% |

| Care perceptions | Participation in decision-making | 4 | 1% |

| Experience/satisfaction with care | 34 | 5% | |

| Health care use | Unscheduled care | 26 | 4% |

| Scheduled care | 13 | 2% |

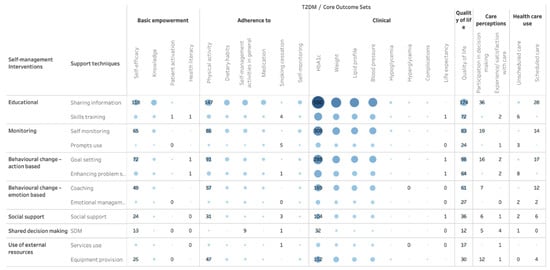

Figure 3 presents the combinations of self-management support techniques and outcomes from the COS. To improve HbA1c, education was most often used, followed or combined with self-monitoring and goal setting. Also, in targeting other outcomes such as self-efficacy, blood pressure and quality of life, education, monitoring and goal setting for T2DM patients are favorite. Other techniques, such as enhancing problem-solving skills, learning how to handle emotions, and shared decision-making, were used relatively less often.

Figure 3. Support techniques for SMIs used to address outcomes for T2DM. The size and color of the bubble indicates the number of studies including each combination presented, with bigger size and darker color referring to more studies included.

7. Risk of Bias of the Included Studies

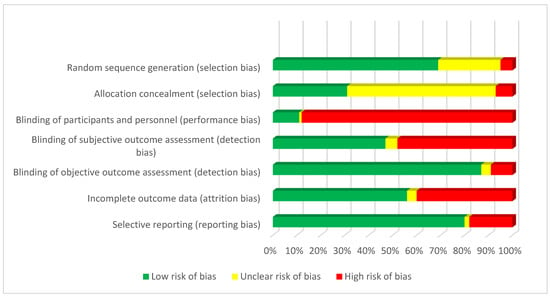

Figure 4 shows that most studies had a low risk of bias in the sequence generation of the random number for the allocation of participants, but there was a lack of clarity in reporting the methods for concealment of the allocation. The main methodological limitation of the included studies was the lack of blinding of the intervention. This limitation affected the assessment of the subjective outcomes (i.e., quality of life) and objective outcomes that might be influenced by the assessor (i.e., blood pressure). Around 40% of the studies also have a significant number of drop-outs during follow-up, raising concerns about the high risk of bias due to attrition in those studies. The risk of selective reporting was more difficult to evaluate as few studies made available their protocols before the publication of the results.

Figure 4. Risk of bias of included RCTs.

References

- WHO. Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of NCDs 2013–2020; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013.

- Lin, X.; Xu, Y.; Pan, X.; Xu, J.; Ding, Y.; Sun, X. Global, regional, and national burden and trend of diabetes in 195 countries and territories: An analysis from 1990 to 2025. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 14790.

- Glasgow, R.E.; Eakin, E.G. Issues in Diabetes Self-Management. The Handbook of Health Behavior Change, 2nd ed.; Springer Publishing Company: New York, NY, USA, 1998; pp. 435–461.

- Peyrot, M.; Rubin, R.R.; Lauritzen, T.; Snoek, F.J.; Matthews, D.R.; Skovlund, S.E. Psychosocial problems and barriers to improved diabetes management: Results of the Cross-National Diabetes Attitudes, Wishes and Needs (DAWN) Study. Diabet. Med. 2005, 22, 1379–1385.

- Effing, T.W.; Bourbeau, J.; Vercoulen, J.; Apter, A.J.; Coultas, D.; Meek, P.; Valk, P.V.; Partridge, M.R.; van Palen, J. Self-management programmes for COPD: Moving forward. Chron. Respir. Dis. 2012, 9, 27–35.

- Carpenter, R.; DiChiacchio, T.; Barker, K. Interventions for self-management of type 2 diabetes: An integrative review. Int. J. Nurs. Sci. 2018, 14, 70–91.

- Jonkman, N.H.; Schuurmans, M.J.; Jaarsma, T.; Shortridge-Baggett, L.M.; Hoes, A.W.; Trappenburg, J.C. Self-management interventions: Proposal and validation of a new operational definition. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 80, 34–42.

- Captieux, M.; Pearce, G.; Parke, H.L.; Epiphaniou, E.; Wild, S.; Taylor, S.J.C. Supported self-management for people with type 2 diabetes: A meta-review of quantitative systematic reviews. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e024262.

- Chrvala, C.A.; Sherr, D.; Lipman, R.D. Diabetes self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review of the effect on glycemic control. Patient Educ. Couns. 2016, 99, 926–943.

- Orrego, C.; Ballester, M.; Heymans, M.; Camus, E.; Groene, O.; Nino de Guzman, E.; Pardo-Hernandez, H.; Sunol, R.; COMPAR-EU Group. Talking the same language on patient empowerment: Development and content validation of a taxonomy of self-management interventions for chronic conditions. Health Expect. 2021, 24, 1626–1638.

More

Information

Subjects:

Health Care Sciences & Services

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

437

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

29 Dec 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No