According to the definition by Rosenberg, sarcopenia is characterized as a loss of muscle mass and function due to aging

[1]. The European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People (EWGSOP2) published an updated definition (2018) for sarcopenia based on three main criteria: 1. Lower muscle strength is accompanied by 2. an impaired muscle quality and quantity and 3. lowered physical performance in the patient. A probable sarcopenia is identified by the first criterion and the diagnosis is confirmed by the second. If all three criteria are met by a patient, sarcopenia is diagnosed as severe. Moreover, sarcopenia is subdivided by its etiology into primary (aging) and secondary (disease/inflammation, inactivity, malnutrition)

[2]. Remarkably, the lowered muscle strength became the major criterion. In 2010, the EWGSOP defined sarcopenia on lower muscle mass as the first, lower muscle strength as the second, and low physical performance as the third criterion. Here, depending on how many criteria were met, the stages presarcopenia (only criterion one), sarcopenia, and severe sarcopenia (all criteria) were defined

[3].

2. PI3K/AKT Pathway

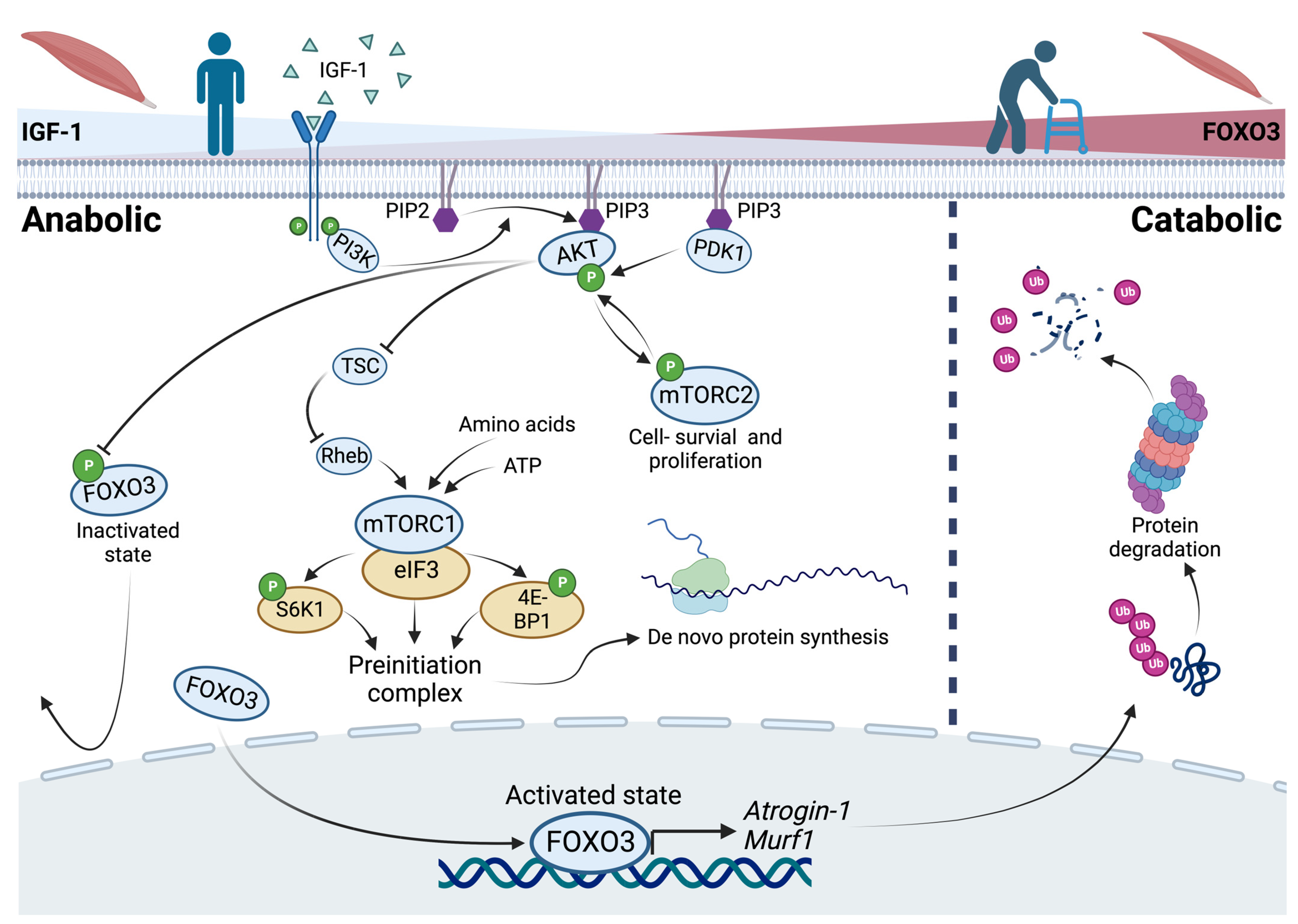

In general, an upregulation of the PI3K/AKT pathway results in inactivation of FOXO3 by phosphorylation. This is governed by IGF-1 as an activator of growth factor receptor protein tyrosine kinases in anabolic situations. In catabolic situations, the absence of IGF-1 results in active FOXO3 that enters the nucleus to bind to the promotor region of the ubiquitin ligases

Atrogin-1 and

Murf-1 [6][7][8][9] (

Figure 1). Both (ATROGIN-1 and MURF-1) are E3 ubiquitin ligases that cause polyubiquitination of proteins and result in proteasomal degradation

[10]. Autophosphorylation of an activated growth factor receptor protein tyrosine kinase, located at the cell membrane, results in recruiting phosphoinositide 3-kinase (PI3K). This kinase converts phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2), a membrane-bound molecule, to phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3). Because of its ability to bind signaling molecules containing a certain pleckstrin homology, PIP3 brings both the serine–threonine protein kinase (AKT) and the phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1) together. If PDK1 is physically close to its downstream target AKT, AKT is activated via phosphorylation. Activated AKT phosphorylates and prevents FOXO3 from entering the nucleus

[11] (

Figure 1). More specifically, AKT phosphorylates FOXO3 at Ser253, S315, and T32 in vitro and in vivo. The phosphorylated FOXO3 is bound by the protein 14-3-3, which isolates FOXO3 as inactive in the cytoplasm

[12]. Notably, there are other proteins that regulate

Foxo3 both negatively and positively (see

[13]). Two examples of positive regulation are demonstrated: At first, MAPK-activated protein kinase 5 can phosphorylate and activate FOXO3 in response to DNA damage

[14]. Also, the AMP-activated protein kinase activates the transcriptional activity of FOXO3 through phosphorylation at low energy levels

[15]. By comparing the contrary regulatory mechanisms of FOXO3, the targetability of

Foxo3 itself is highlighted.

Figure 1. The PI3K/AKT pathway and the role of FOXO3 in anabolic and catabolic conditions as a reflection of changes in the catabolic state, like aging. In anabolic situations, recruitment of phosphoinositide-3-kinases (PI3K) to an activated growth factor receptor results in the conversion of phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) to phosphatidylinositol-3,4,5-trisphosphate (PIP3) bringing the serine–threonine protein kinase (AKT) and phosphoinositide-dependent kinase 1 (PDK1) together. AKT inhibits the Forkhead-Box Protein O3 (FOXO3) by phosphorylation. Further, AKT promotes cell survival via the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 2 (mTORC2) and indirectly promotes protein synthesis via the mammalian target of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1). In catabolic situations, FOXO3 regulates the expression of its downstream targets Atrogin-1 and Murf-1 as ubiquitin ligases that cause proteasomal degradation of proteins.

3. Post-Translational Modification of FOXO3: Acetylation and Deacetylation

Another regulatory mechanism of FOXO3 involves post-translational modification through acetylation and corresponding deacetylation. The CBP/p300 coactivator mediates acetylation, while SIRT1 and SIRT2 mediate deacetylation

[16]. However, acetylation of FOXO3 has been reported to induce its cytosolic translocation and consequent proteasomal degradation in C57BL/6J mice in vivo

[17].

On the other hand, it was found that SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of FOXO3 increases its activity in the nucleus accumbens of C57BL/6J mice in vivo

[18]. Remarkably, SIRT1-mediated deacetylation of FOXO3 also leads to a decrease in its activity in vitro

[19]. Another study confirmed that FOXO3 activity was reduced by SIRT1 deacetylation as well as by SIRT2 in vitro

[20]In conclusion, the post-translational modification of FOXO3 appeared to be intricate. Although its acetylation seemed to reduce its activity, deacetylation has been observed to both increase and decrease FOXO3 activity

[16].

4. De Novo Protein Synthesis via mTOR Signaling

In vitro studies revealed that IGF-1 caused myotube hypertrophy in C2C12 myoblasts (an immortalized myoblast cell line used to study myogenesis) to be mediated via the PI3K/AKT/mTOR pathway, which was prevented by applying Rapamycin, an inhibitor of the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)

[21]. The protein kinase mTOR is contained in two complexes with different functions. The first one, mTORC1, mediates cell growth and is sensitive to rapamycin. The other one, mTORC2, mediates cell survival and proliferation but is insensitive to rapamycin

[22]. Increased ATP or amino acid levels, predominantly in anabolic conditions, positively regulate the activity of mTORC1 independently

[23][24]. Activated mTORC1 binds to eIF3 and phosphorylates S6K1 and 4E-BP1, leading to an assembly of the preinitiation complex and therefore de novo protein synthesis in vitro

[25][26]. Another positive but indirect regulator of mTORC1 is AKT itself. AKT phosphorylates the tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), leading to a release from the GTPase Rheb which in turn activates mTORC1

[27]. In conclusion, a positive effect of mTORC1 in terms of myotube hypertrophy and protein synthesis is described. In contrast, an in vivo mouse model revealed that mTORC1 inhibition by rapamycin had positive effects on age-related muscle loss, whereas TSC knockout mice (higher levels of active mTORC1) showed a sarcopenic muscle fiber pattern due to impaired stability of the neuromuscular junction

[28]. This implies that in addition to atrophy, the etiology of denervation plays an important role in sarcopenia. However, mTORC2 mediates the IGF-1 signaling as a direct target of AKT. Moreover, PDK1 phosphorylates and activates AKT, yet activates mTORC2 by phosphorylation. Via a positive feedback loop, the activation of AKT is boosted by phosphorylation of mTORC2

[29][30].

Fiber Type Composition during Aging

In the aging of skeletal muscle, different types of fibers follow different paths, which is important to understand for the development of a specific molecular therapy. A comparative study analyzing human M. vastus lateralis biopsies of younger (23–31 years) and older (68–70 years) men identified myosin heavy chain (MHC) type I fibers as constant in size upon aging, but MHC type IIa and IIx fibers decreasing in size in older subjects

[31]. The phenomenon of a type II fiber size decrease in aging was identified to be reversed when resistance training (RT) was applied. As a result of 6 months of training, type II fiber size was increased by RT, but type I fibers remained constant in size in younger (23 years) compared to older (71 years) men

[32]. The different muscle types were also rigorously studied in a mouse model. Fast-twitch gastrocnemius muscle (type II) was identified to undergo the highest impairment by aging-dependent atrophy, while slow-twitch (type I) soleus muscle remained unaffected. This finding mirrors the observed human fiber type II atrophy due to aging, as described above

[33]. As another response to exercise, the peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor γ coactivator 1α (PGC-1α) is more highly expressed in human and rat muscle in in vivo models after endurance training

[34][35][36].

Interestingly, PGC-1α transgenic mice are protected from denervation and fasting-induced muscle atrophy and show a reduced expression of genes required for glycolysis and oxidative phosphorylation

[37]. This suggests that PGC-1α creates a milieu typically preferred by type I fibers. Consequently, if the PGC-1α gene was placed downstream of the muscle creatine kinase and subsequently selectively expressed in skeletal and cardiac muscle, type II muscle fibers switched and became type I fibers, indicated by the expression of typical genes for type I fibers (such as troponin I, myoglobin, and cytochrome C) and showed a higher fatigue resistance, induced by electrical stimulation

[38][39]. Interestingly, PGC-1α is able to block FOXO3 binding to its responsive element on the

Atrogin-1 promotor

[37]. Both ubiquitin ligases (

Atrogin-1 and

Murf-1) have been identified to be expressed more highly and selectively in cardiac and skeletal muscle during muscle atrophy in an in vivo mouse model

[40]. Further, skeletal muscle atrophy was observed to be more severe in glycolytic (IId/x and IIb) compared to oxidative (I and IIa) fibers in vivo

[41]. These findings suggest a link between FOXO3 and its target genes (

Atrogin-1 and

Murf-1) and therefore the PI3K/AKT pathway to sarcopenia, highlighting FOXO3 as a possible target.

5. The Influence of Physical Activity and Aging upon the Expressional Profile of FOXO3 in Humans

Foxo3 content and its target genes have also been studied in the context of physical activity. Here, in mice with unilaterally immobilized hindlimbs, immobilization caused an increase in FOXO3 acetylation and a reduction in gastrocnemius muscle weight in vivo. However, this increase was reversible. Within a few days of unrestricted movement, FOXO3 acetylation levels decreased again. The authors conclude that acetylation of FOXO3 promotes muscle atrophy, while deacetylation of FOXO3 increases muscle regeneration potential, highlighting the importance of physical activity

[42].

Two in vivo human studies of younger (20 years) and older (70 years) healthy male and female subjects independently showed that

ATROGIN1 and

MURF1 expression did not change during aging

[43][44]. Further investigations showed that ubiquitin expression did not change in human rectus abdominis muscles either

[45]. However, the overall ubiquitin protein content showed an age-dependent increase. Ubiquitin protein levels were increased in older (70–79 years) human quadriceps muscle biopsies compared to younger (20–29 years) subjects’ biopsies

[46]. In contrast, another study identified increased levels of

FOXO3 and

MURF1 (but not

ATROGIN1) in older healthy females (85 years) compared to younger females (23 years) in M. vastus lateralis biopsies. After a single session of RT, the

FOXO3 expression remained unchanged, whereas

ATROGIN1 expression was markedly increased in older subjects, and

MURF1 accumulated in both groups

[47]. A follow-up study in older women (70 years) performing long-term training (12 weeks on a cycle ergometer) revealed decreased

FOXO3 expression levels with no significant effect on the protein levels and no change in expression of

ATROGIN1 and

MURF1 [48] (Table 1). An additional comparative study investigated 12 weeks of RT with a focus on FOXO3 protein content in younger (24 years) and older (85 years) females. In the untrained state, older subjects showed lower levels of cytosolic phosphorylated FOXO3 (P-FOXO3) and therefore less inactivated FOXO3. After the training period, increased levels of total nuclear FOXO3 were observed in older subjects. On the other side, younger subjects showed higher levels of P-FOXO3 in response to RT. These results indicate an increase in total nuclear FOXO3 due to aging and impaired nuclear phosphorylation and thus inactivation in response to resistance training, which may attenuate the beneficial effect of physical activity

[49] (

Table 1).

Table 1. FOXO3 levels upon different (training) conditions.

In summary, these results suggest that the aging muscle is atrophic through increased protein content of Ubiquitin and nuclear FOXO3. Moreover, it suggests an imbalanced anabolic/catabolic interaction, linking FOXO3 as a potential molecular target for the clinical treatment of sarcopenia.

Therapeutical Targets

To evaluate the targetability of the PI3K/AKT pathway, the current prospects can be subdivided into an AKT-dependent and an AKT-independent treatment strategy.