Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alessio Calantropio | -- | 3332 | 2023-12-18 11:37:52 | | | |

| 2 | Alessio Calantropio | Meta information modification | 3332 | 2023-12-18 11:38:51 | | | | |

| 3 | Rita Xu | -7 word(s) | 3325 | 2023-12-19 03:02:02 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Calantropio, A.; Chiabrando, F. Underwater Cultural Heritage. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52871 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Calantropio A, Chiabrando F. Underwater Cultural Heritage. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52871. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Calantropio, Alessio, Filiberto Chiabrando. "Underwater Cultural Heritage" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52871 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Calantropio, A., & Chiabrando, F. (2023, December 18). Underwater Cultural Heritage. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52871

Calantropio, Alessio and Filiberto Chiabrando. "Underwater Cultural Heritage." Encyclopedia. Web. 18 December, 2023.

Copy Citation

Underwater cultural heritage (UCH) means "all traces of human existence having a cultural, historical or archaeological character which have been partially or totally under water, periodically or continuously, for at least 100 years such as (i) sites, structures, buildings, artifacts and human remains, together with their archaeological and natural context; (ii) vessels, aircraft, other vehicles or any part thereof, their cargo or other contents, together with their archaeological and natural context; and (iii) objects of prehistoric character".

underwater cultural heritage (UCH)

marine protected areas (MPAs)

marine environment

1. Introduction

The marine environment has always interested scientists and researchers in various disciplines. With more than 70% of the planet’s surface covered by water, marine space is still largely unexplored in many respects. Over time, the international community has achieved an ever-greater awareness of the cultural and historical value of the priceless heritage that our seas and oceans conceal [1][2][3].

Underwater cultural heritage (UCH) means “all traces of human existence having a cultural, historical or archaeological character which have been partially or totally underwater, periodically or continuously, for at least 100 years” [4].

The importance of studying and preserving UCH is stated in three important international conventions and charters: the 1982 UNCLOS (United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea), the 1996 ICOMOS (International Council on Monuments and Sites) Charter on the Protection and Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage, and the 2001 UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage. The 2001 convention recommends protecting ancient shipwrecks or submerged archaeological sites in situ before considering recovery. In marine archaeology, many wooden or metallic artifacts are found in different states of conservation, depending on the environment in which they are discovered [5], and their recovery is not always the best strategy for pursuing their preservation and conservation.

Underwater cultural heritage constitutes an invaluable resource that needs acknowledgment and proper treatment so that it may continue to offer significant benefits to humankind. However, UCH has been neglected in most marine planning attempts despite its indisputable value. Lately, however, the opportunities and challenges for UCH have been considerably different [6].

2. International Charters and Conventions on UCH

2.1. Chronological Analysis of the Evolution of the Legislation on UCH

It is necessary to wait until 1982 to see the birth of the first international text [7], which, although it was drafted to outline the laws of the sea, also includes two articles that refer specifically to underwater archaeological sites and historical objects and provides that the same “shall be preserved or disposed of for the benefit of mankind as a whole, particular regard being paid to the preferential rights of the State or country” [7].

The first specific reference to the submerged cultural heritage dates back to the ICOMOS charter of 1990, which defines the archaeological heritage as “all vestiges of human existence and consists of places relating to all manifestations of human activity, abandoned structures, and remains of all kinds (including subterranean and underwater sites), together with all the portable cultural material associated with them” [8].

The focus of the charter spans structures and infrastructures, such as ports, harbors, and marine systems. Interest has been growing because of the development of underwater exploration technologies and techniques, which has unfortunately opened the road to looters, with subsequent damage to the heritage itself. This prompted the European Council to adopt the 1992 European Convention on the Protection of Archaeological Heritage, with the recommendation to create archaeological parks for underwater heritage [9].

The International Committee on the Underwater Cultural Heritage (ICUCH) was founded in 1991 by ICOMOS Australia to promote international cooperation in the protection and management of underwater cultural heritage and to advise the International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS) on issues related to underwater cultural heritage around the world. As a supplement to the 1990 charter, in 1996, ICUCH authored the drafts that led to the ratification of the first document on protecting and managing underwater heritage, i.e., the Charter on the Protection and Management of the Underwater Cultural Heritage [10]. Hand in hand with the need for knowledge and study, awareness of the importance of this type of heritage has also developed in terms of the significant risks to which it is subject. Considerable importance is given to the increasing interest on the part of collectors in finds that come from the seabed; this alarming development is in part linked to recent advances in diving technology and may give rise to forms of looting. The enhancement of underwater heritage must deal with the problems of “protection”, whose solutions are not always easily feasible in a marine context; the action of promoting a submerged discovery, if not adequately reasoned (including through awareness programs for the local population), inevitably puts it at risk of depredation.

In the declaration of Syracuse, adopted in 2001 at the end of a conference on the cultural heritage of the Mediterranean Sea, it was outlined that “the Mediterranean countries have a special responsibility to ensure that the submarine cultural heritage they share is made known and preserved for the benefit of humankind” [11].

Following the International Conference, “Means for the Protection and Touristic Promotion of the Marine Cultural Heritage in the Mediterranean”, held in Palermo and Syracuse, Italy, on 8-10 March 2001 [11], the most recent international document on the subject as of today is the 2001 UNESCO Convention on the Protection of Underwater Cultural Heritage.

This document proposes (for the very first time) the definition of underwater cultural heritage as “all traces of human existence having a cultural, historical or archaeological character which have been partially or totally under water, periodically or continuously, for at least 100 years such as (i) sites, structures, buildings, artifacts and human remains, together with their archaeological and natural context; (ii) vessels, aircraft, other vehicles or any part thereof, their cargo or other contents, together with their archaeological and natural context; and (iii) objects of prehistoric character” [4].

The Convention sets out basic principles for the protection of underwater cultural heritage by outlining four main principles:

“Obligation to Preserve Underwater Cultural Heritage—State Parties should preserve underwater cultural Heritage and take action accordingly. This does not mean that ratifying states would necessarily have to undertake archaeological excavations; they only have to take measures according to their capabilities. The Convention encourages scientific research and public access.

In situ preservation as the first option—The in situ preservation of underwater cultural Heritage (i.e., in its original location on the seafloor) should be considered as the first option before allowing or engaging in any further activities. The recovery of objects may, however, be authorized for the purpose of making a significant contribution to the protection or knowledge of underwater cultural Heritage.

No Commercial Exploitation—The 2001 Convention stipulates that underwater cultural Heritage should not be commercially exploited for trade or speculation and that it should not be irretrievably dispersed. This regulation is in conformity with the moral principles that already apply to cultural heritage on land. It is not to be understood as preventing archaeological research or tourist access.

Training and information Sharing—States Parties shall cooperate and exchange information, promote training in underwater archaeology and promote public awareness regarding the value and importance of underwater cultural heritage.”

Following UNESCO’s Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage (2001), the new stage of the current process of reappropriation of cultural heritage as a common value, a “popular” asset, is represented by the Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society [12], adopted by the Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe on the 13 October 2005 in Faro, effective since 1 June 2011 and ratified by Italy on the 23 September 2020 (House of Representatives). The Convention had the merit of defining an innovative and revolutionary concept of cultural heritage (CH), intended as the body of resources inherited from the past, identified by the citizens as the reflection and expression of their values, beliefs, knowledge, and traditions in continuous evolution. It recognizes the right of the single citizen and all humanity to benefit from CH, tempered by the responsibility of respecting it. These principles are the basis for the chain of research, conservation, protection, management and participation, and cultural dialogue, promoting the birth of a sustainable and multicultural social, political, and economic environment. It is a fact that UCH is increasingly required to have a social return beyond the cultural aspect; a positive impact on a community’s economic and social fabric is sought. On the other hand, the European Union guidelines promote Blue Growth and responsible and sustainable tourism linked to the sea and UCH.

Experiencing the past underwater has rapidly become an enormous asset in the leisure industry and the “experience economy”. This development implies risks and opportunities for protection as not all UCH can be enjoyed through direct access for various reasons; these include the position, depth, and safety/integrity of the assets and the safety and diving capabilities of researchers, citizens, stakeholders, and tourists.

This is particularly true for the submerged deposits of shipwrecks (hull or cargo and onboard equipment). Those that contain inorganic cargo and are located at a limited depth can be accessible, but only under favorable visibility conditions, and to a few divers, who are only a small percentage of the community interested in exploring its past.

After more than 20 years of the Sofia Charter for the Protection and Management of the Underwater Cultural Heritage [10] (5–9 October 1996), a Udine summit (8–9 September 2022) outlined the most recent experiences in the field in the Italian panorama. The discussions and considerations led to a shared proposal, the Udine Charter for the Underwater Archaeology [13]; this document represents the outcome of an intense debate within the scientific community regarding UCH and the related challenges to guaranteeing the development of the research while at the same time promoting a virtuous model of public engagement with the archaeological heritage.

On the 8th and 9th of September 2022, the first workshop aiming to update the Udine Charter took place to ensure the inclusion of the aspects more related to internal waters, i.e., rivers and lakes, and the incorporation of opportunities offered through the development of new remote sensing technologies.

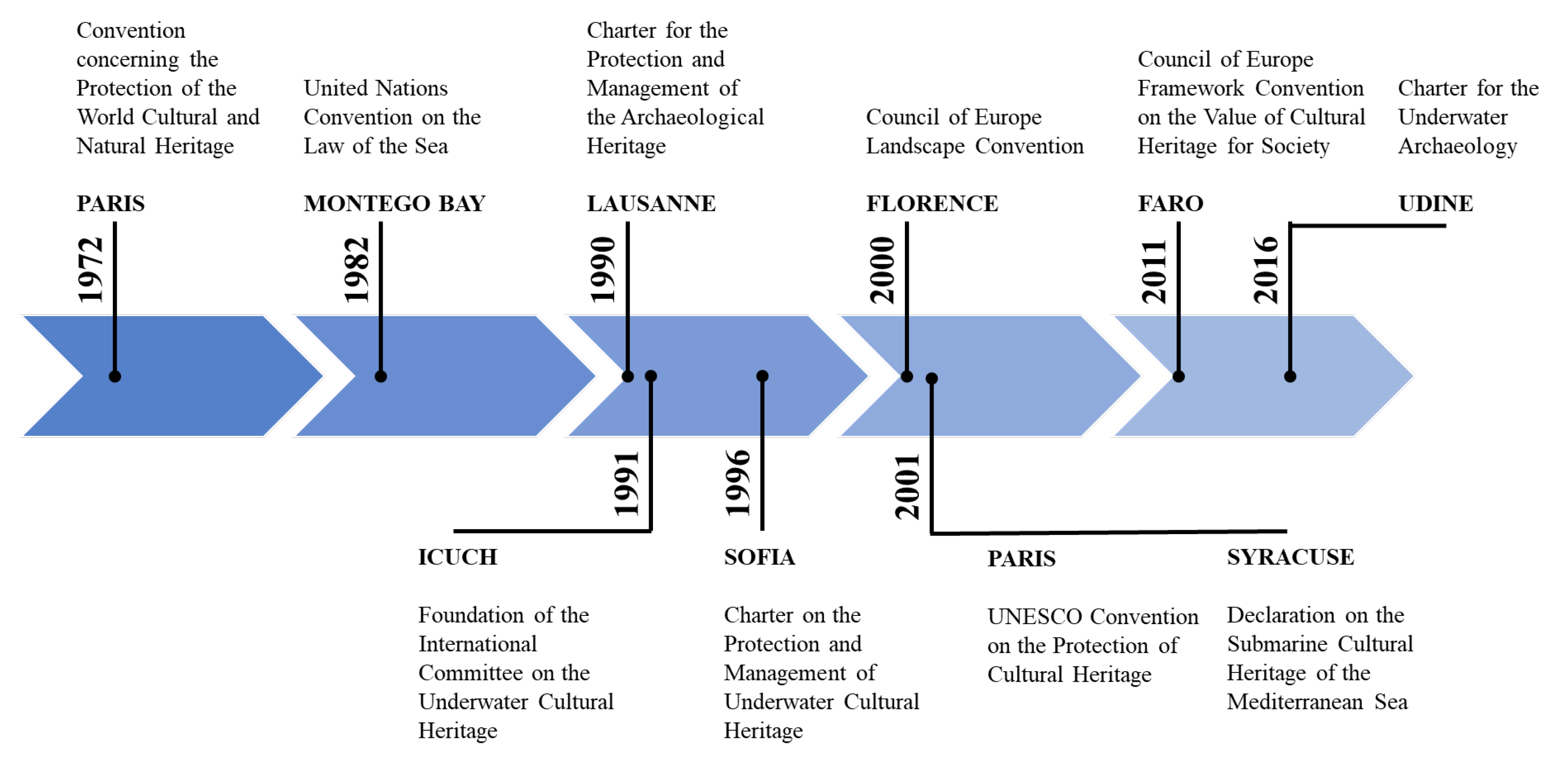

The conventions, charter, and declarations listed above are summarized in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Main conventions and charters on the concept of underwater cultural heritage in recent decades.

2.2. The Concept of In Situ Conservation

The long evolution of the concept of heritage also affects the submarine heritage; the latter is therefore not configured as a nineteenth-century statement but as a very recent conquest. It is noteworthy that in the 2001 Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage [4], for the first time, in situ conservation is explicitly indicated as the preferred choice. It also underlines the importance of and respect for the historical context of cultural heritage sites and their scientific relevance, recognizing that this heritage is (under normal circumstances and for some materials) preserved underwater thanks to the low rate of deterioration due to the absence of oxygen. Therefore, recovery from the seabed is not always automatically justified. Moreover, considering the state of conservation and submersion methods, recovery is not always the action that guarantees maximum preservation of the asset.

For this reason, it is important to consider innovative technologies for documentation and study, even for those who do not have the skills or the ability to go underwater. These technologies should be adopted without ignoring the need for historical and archaeological knowledge, which is indispensable for a careful and intelligent application of today’s technical solutions.

In situ conservation of underwater archaeological heritage is a complex operation in terms of methodological approach and operational workflow. It requires many experts (archaeologists, geomatic specialists, engineers, chemists) to integrate the available archaeometric information. This approach should not be considered to be a sum of the different contributions but rather a complementary coordination towards the improvement of the knowledge of the heritage.

3. The Marine Environment and the Coastal Landscape

3.1. The Notions of “Environment” and “Landscape”

The progressive emergence of the notion of “environment”, which did not exist in the 1948 Italian Constitution, was introduced in Italy by the Franceschini Commission (Commissione d’indagine per la tutela e la valorizzazione del patrimonio storico, archeologico, artistico e del paesaggio, created with the law L. 310 of 1964).

The management and protection of cultural heritage and the natural environment encountered various difficulties in Italy after the Second World War, following the emergence of the concept of “cultural heritage” instead of “historical-artistic heritage”.

Protecting the natural environment has suffered from a series of problems that are still unresolved today and which are linked to the expression “cultural and environmental heritage”, which seems to indicate that environmental heritage is not also cultural. As Oreste Ferrari writes, this “may seem like a simple question of terminology, but in reality, it is a substantial question, which has determined different types of behavior in the protection action” [14].

In Italy, the documentation of archaeological underwater and coastal sites has been, in recent years, an essential subject at various conferences and seminars, as the interest in this kind of heritage has increased over the last few decades. In particular, (again in Italy), numerous and significant disastrous events (earthquakes, land exploitation, coastal erosion, landslides, and floods caused by indiscriminate deforestation) have constituted further difficulties that require collective attention and public intervention.

The proceedings of World Environment Day (Held in Rome on 5 June 1985) subsequently promoted the unequivocal interconnection between the “historical-cultural” environment and the “physical-natural” environment. Thanks to this, diagnostic and monitoring systems have been developed that facilitate map-based documentation of the factors that increase the vulnerability of cultural heritage, with particular reference to anthropogenic and environmental phenomena.

The submerged heritage is closely linked to the marine and coastal landscape in which it is located, even though at the beginning of the twentieth century, the protection of landscape assets and the notion of “landscape” was legally considered in the same way as that of “things of art” [15]. At the beginning of the twenty-first century, since there was a need for a vision broader than the concept, researchers find a reference to the marine landscape in the European Landscape Convention, which extended the notion of landscape to “the entire territory of the Parties”, including “natural, rural, urban and peri-urban areas […], land, inland water, and marine areas” [16].

The concept of landscape and the definition of landscape heritage can also be extended to the coastal areas. Westerdahl introduced the first application of this concept internationally as “the whole network of sailing routes, with ports, havens, and harbors along the coast, and its related constructions and other remains of human activity, underwater as well as terrestrial” based on this approach; the landscape defined as such should be compared “to its terrestrial counterpart, but not just as an extension of the latter” also including “shipping, shipbuilding and fishing and their respective hinterlands, with nodal points of coast towns and land roads, fords, ferries, and inland waterways” [17].

3.2. Coastal Areas and the Land–Sea Duality

The relationship between the coastal areas and the land–sea duality has a strong cultural connotation and emblematically represents the symbol of the underwater archaeological heritage, whose conservation cannot preclude the study of its connections with the land. For this specific purpose, it remains crucial to develop new ways of integrating heterogeneous data in specific GISs (Geographic Information Systems), which can represent a good starting point for each conservation and valorization activity regarding the archaeological heritage and the landscape heritage.

The concept of the protection and valorization of coastal areas and the complex relation between sea and land have strong cultural values represented by the importance of many archaeological findings, whose preservation must be linked to the evaluation of historical and environmental dynamics that are in common with land above sea level.

Coastal areas have always been dynamic; natural factors and various anthropogenic factors have affected the seashore (especially in recent years). The study of underwater archaeological sites requires understanding and virtually reconstructing the coastline based on the interpretation of archaeological data and available geomatics, geologic, and geophysics data. Integrating data from those disciplines fosters the acquisition of knowledge about the coastal landscape and archaeology of coastal settlements.

The link between geological phenomena (proximity to a river, composition of the soil and the rocks) and the presence of archaeological evidence is very important; it is the main reason it is possible to find archaeological remains a hundred meters inland from the coastline. In the Mediterranean Sea, we have witnessed a coastline retreat that caused the submersion of human-made artifacts and structures (today, those sites vary in depth, from a few centimeters up to 3–4 m).

The study of the sea level and the interpretation of the causes behind the submersion of such archaeological remains are complex; there are several reasons, such as eustatic sea level change due to changes in the volume of water in the world’s oceans, net changes in the volume of the oceanic basins, vertical tectonic movements, coastal erosion, or mineral deposits formed during the accumulation of sediment on the bottom of rivers and other bodies of water. Each of those causes is related to a different method of studying how and why the phenomena occurred.

The changing coastline of the Mediterranean Sea over the last 2000 years has been drafted by Antonioli and Leoni [18] based on measurements performed on the Roman pool of the imperial period located in the Tyrrhenian Sea. Those structures’ strong relations with the sea level allowed us to understand useful information about that period’s historical sea level (and, therefore, its coastline).

Harbors, ports, and pools annexed to Roman villas were built to function with the activities related to the sea, and they demonstrated strong relations between the sea level and the geographical context. Documenting the relationships between the ports, the cities, and the territories is crucial to understanding their role in general maritime politics [19].

The integration of geomatics, geophysics, and archaeological data allows us to understand and reconstruct the coastline as it was in ancient ages and therefore allows not only the comprehension and study of the coastal landscape and the actuation of countermeasures against coastal erosion but also an understanding of the human impact on the recent phenomenon of climate change. This is helped by the possibility of chronologically classifying the archaeological remains along the shore.

The most recent geo-archaeological studies related to the Mediterranean Sea show that the main reason for the submersion of underwater heritage is linked to a slow increase in the sea level, which has caused a slight but noticeable regression of the coastline over the last 2000 years [20][21][22], with some more important tectonic movements (mainly local) such as the case of Campi Flegrei, which have caused a more significant submersion of several meters below the current sea level [23].

The study of this kind of data is important to define the relations between the submerged archaeological heritage and the coastline and the land, with the period and the context of the submersion also being considered in order to define a useful connection for valorization and protective actions.

In an optimal situation, MPA valorization and conservation projects should aim to contextualize the underwater heritage in the surrounding framework from an environmental and landscape point of view. Valorization and conservation projects should also ensure a system of services for enabling the fruition of the heritage; in this way, importance is given not only to the conservation but also to the valorization, keeping a balance between the anthropic risk and the need for promotion and making “visible the invisible”. This must be linked with research activities that aim to communicate scientific data in a fast and easy way, not only to scientists but also to the public (not from the point of view of tourist marketing, but for the promotion of the cultural and historical point of view of specific places and regions).

The idea of the coastal landscape, and the landscape in general, is not the aesthetic “panoramic view” concept, but rather the identity of the places, a compresence of nature, culture, and history, and the assumption of the aesthetic identity of the landscape as an integration of these three elements [24].

References

- Goncalves, R.M. Legal aspects of the underwater cultural heritage in Spain. Current state legislation. Aspectos jurídicos do patrimônio cultural subaquático na Espanha. A legislação estatal atual. Veredas do Direito 2017, 14, 39.

- Miranda Gonçalves, R. La Protección Del Patrimonio Cultural Subacuático En La Convención Sobre La Protección Del Patrimonio Cultural Subacuático De 2001. Rev. Derecho-Univ. Católica Del Norte 2017, 24, 247–262.

- Ribeiro, S.G. Miranda Gonçalves, R. El régimen jurídico del patrimonio cultural subacuático. Especial referencia al ordenamiento jurídico español. Valencia: Tirant lo Blanch. Gladius Scientia. Revista de Seguridad del CESEG 2020, 2, 1–2.

- United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. Convention on the Protection of the Underwater Cultural Heritage. In Proceedings of the Records of the General Conference: 31st Session, Paris, France, 15 October–3 November 2001.

- Bandiera, A.; Alfonso, C.; Auriemma, R.; Di Bartolo, M. Monitoring and Conservation of Archaeological Wooden Elements from Ship Wrecks Using 3D Digital Imaging. In Proceedings of the 2013 Digital Heritage International Congress (DigitalHeritage), Marseille, France, 28 October–1 November 2013; Volume 1, pp. 113–118.

- Papageorgiou, M. Stakes and Challenges for Underwater Cultural Heritage in the Era of Blue Growth and the Role of Spatial Planning: Implications and Prospects in Greece. Heritage 2019, 2, 1060–1069.

- United Nations. UNCLOS III, United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (Law of the Sea Treaty); United Nations: Montego Bay, Jamaica, 1982.

- International Committee for the Management of Archaeological Heritage (ICAHM). Charter for the Protection and Management of the Archaeological Heritage; ICOMOS: Charenton-le-Pont, France, 1990.

- Council of Europe. European Convention on the Protection of the Archaeological Heritage; Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 1992; Volume 143.

- International Council on Monuments and Sites (ICOMOS). Charter on the Protection and Management of Underwater Cultural Heritage; ICOMOS: Charenton-le-Pont, France, 1996.

- Università di Milano “Bicocca” (Dipartimento Giuridico delle Istituzioni Nazionali ed Europee); Regione Siciliana (Assesorato dei Beni Culturali ed Ambientali e della Pubblica Istruzione); Università degli Studi di Palermo, Facoltà di Economia (Istituto di Diritto del Lavoro e della Navigazione). Syracuse Declaration on the Submarine Cultural Heritage of the Mediterranean Sea. In Proceedings of the Conference “Strumenti per la Protezione del Patrimonio Culturale Marino nel Mediterraneo”, Palermo—Siracusa, Italy, 8–10 March 2001.

- The Member States of the Council of Europe. Council of Europe Framework Convention on the Value of Cultural Heritage for Society (CETS No. 199); Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2005.

- Capulli, M. Il patrimonio culturale sommerso. Ricerche e proposte per il futuro dell’archeologia subacquea in Italia; Forum Edizioni: Udine, Italy, 2019; ISBN 978-88-328-3112-2.

- Ferrari, O. Beni Culturali. In Enciclopedia del Novecento; II Supplemento; Treccani: Rome, Italy, 1998.

- Alibrandi, T. Beni Culturali e Ambientali. In Enciclopedia Giuridica; Treccani: Rome, Italy, 1988.

- The Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe. Council of Europe Landscape Convention; The Committee of Ministers of the Council of Europe: Strasbourg, France, 2000.

- Westerdahl, C. The Maritime Cultural Landscape. Int. J. Naut. Archaeol. 1992, 21, 5–14.

- Antonioli, F.; Leoni, G. Holocene sea level rise research using archaeological site (Siti archeologici sommersi e loro utilizzazione quali indicatori per lo studio delle variazioni recenti del livello del mare). Ital. J. Quat. Sci. 1998, 11, 122–139.

- Felici, E. La Ricerca Sui Porti Romani in Cementizio: Metodi e Obiettivi. In Proceedings of the VIII Ciclo di Lezioni sulla Ricerca Applicata in Archeologia: Archeologia Subacquea, Come Opera l’archeologo Sott’acqua. Storie dalle acque; Volpe, G., Ed.; All’insegna del Giglio, Sesto Fiorentino: Florence, Italy, 1998; pp. 275–340.

- Benjamin, J.; Rovere, A.; Fontana, A.; Furlani, S.; Vacchi, M.; Inglis, R.H.; Galili, E.; Antonioli, F.; Sivan, D.; Miko, S.; et al. Late Quaternary Sea-Level Changes and Early Human Societies in the Central and Eastern Mediterranean Basin: An Interdisciplinary Review. Quat. Int. 2017, 449, 29–57.

- Lambeck, K.; Antonioli, F.; Purcell, A.; Silenzi, S. Sea-Level Change along the Italian Coast for the Past 10,000 yr. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2004, 23, 1567–1598.

- Lambeck, K.; Purcell, A. Sea-Level Change in the Mediterranean Sea since the LGM: Model Predictions for Tectonically Stable Areas. Quat. Sci. Rev. 2005, 24, 1969–1988.

- Pappalardo, U.; Russo, F. Il Bradisismo Dei Campi Flegrei: Dati Geomorfologici Ed Evidenze Archeologiche. In Forma Maris; Gianfrotta, P.A., Maniscalco, F., Eds.; Massa Editore: Neaples, Italy, 2001; pp. 107–119.

- D’Angelo, P. Estetica e Paesaggio; Il Mulino: Bologna, Italy, 2009; ISBN 978-88-15-13234-5.

More

Information

Subjects:

Archaeology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.7K

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

19 Dec 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No