Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Federica Canfora | -- | 3470 | 2023-12-12 09:14:09 | | | |

| 2 | Mona Zou | Meta information modification | 3470 | 2023-12-14 09:18:51 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Canfora, F.; Ottaviani, G.; Calabria, E.; Pecoraro, G.; Leuci, S.; Coppola, N.; Sansone, M.; Rupel, K.; Biasotto, M.; Di Lenarda, R.; et al. Chronic Orofacial Pain. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52608 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Canfora F, Ottaviani G, Calabria E, Pecoraro G, Leuci S, Coppola N, et al. Chronic Orofacial Pain. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52608. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Canfora, Federica, Giulia Ottaviani, Elena Calabria, Giuseppe Pecoraro, Stefania Leuci, Noemi Coppola, Mattia Sansone, Katia Rupel, Matteo Biasotto, Roberto Di Lenarda, et al. "Chronic Orofacial Pain" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52608 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Canfora, F., Ottaviani, G., Calabria, E., Pecoraro, G., Leuci, S., Coppola, N., Sansone, M., Rupel, K., Biasotto, M., Di Lenarda, R., Mignogna, M.D., & Adamo, D. (2023, December 12). Chronic Orofacial Pain. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52608

Canfora, Federica, et al. "Chronic Orofacial Pain." Encyclopedia. Web. 12 December, 2023.

Copy Citation

In exploring chronic orofacial pain (COFP), it's very important to highlight its global impact on life quality and critiques current diagnostic systems, including the ICD-11, ICOP, and ICHD-3, for their limitations in addressing COFP’s complexity. The mismanagement of pain not only leads to severe physical, psychological, and social repercussions but also incurs substantial economic costs, both in terms of healthcare expenditure and lost productivity.

orofacial pain

burning mouth syndrome

chronic pain

biopsychosocial

trigeminal neuralgia

ICD-11

ICOP

ICHD-3

DSM-5

1. Introduction

Chronic pain, affecting an estimated 30% of the global population, ranks as one of the predominant reasons for seeking medical care [1][2]. Despite the higher mortality associated with conditions such as heart attacks, strokes, infectious diseases, cancer, and diabetes, chronic pain remains a leading cause of human suffering and disability, surpassing many other health challenges in its impact on quality of life [1][3][4].

The mismanagement of pain not only leads to severe physical, psychological, and social repercussions but also incurs substantial economic costs, both in terms of healthcare expenditure and lost productivity [5][6][7].

Patients enduring chronic pain often experience a protracted journey through the healthcare system, spanning months or years, without adequate recognition of their condition [8][9]. This lack of validation can contribute to feelings of alienation and exacerbate their suffering [10]. The inability of healthcare systems to effectively acknowledge and address the multifaceted impact of chronic pain has emerged as a critical issue, necessitating urgent attention in medical and dental practices as well as at the policy level [11][12][13].

Understanding and effectively treating chronic pain is not just a clinical challenge but a societal imperative, in medicine, dentistry, and for the national healthcare system [14][15].

The face and mouth hold special significance in human physiology and social interaction, making pain in this region particularly complex [16][17]. The prevalence of COFP is notable, with approximately 10% of chronic pain cases falling within this category [18][19][20]. It encompasses a range of conditions, from trigeminal neuralgia to burning mouth syndrome, each presenting unique challenges in terms of diagnosis and management [21][22][23].

A central theme of the paper is the exploration of the biopsychosocial model of chronic pain [24][25]. This model emphasizes that pain is not solely a physical symptom but is significantly influenced by psychological and social factors [26][27].

This understanding is crucial for healthcare professionals as it necessitates a highly individualized approach to pain management [28][29][30].

According to the International Association for the Study of Pain (IASP), “pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage” [31][32][33].

The IASP task force expanded this definition in 2020 by adding six key notes [33]:

Pain is always a personal experience that is influenced by biological, psychological, and social factors;

Pain and nociception are different phenomena. Pain cannot be solely deduced from the activity of sensory neurons;

Individuals learn the concept of pain through their life experiences;

The individual’s personal history of pain should be respected;

Although pain usually plays an adaptive role, it can have negative effects on social, psychological, and functional well-being;

Verbal description is just one of many behaviors used to express pain. The inability to communicate does not negate the possibility that a human or non-human being experiences pain [33].

Chronic pain is defined as pain that persists beyond the normal time of healing that is associated with a particular type of damage or disease [34]. According to the IASP task force, chronic pain is defined as persistent or recurrent pain lasting more than 3 months [35].

Pain, a complex and multifaceted experience, can be categorized into three distinct types based on mechanistic differences: nociceptive, neuropathic, and nociplastic pain [36].

Nociceptive pain is defined as pain that arises from actual or potential damage to non-neural tissue due to the stimulation of nociceptors [33]. Therefore, neural tissue is generally healthy, and signal transmission is normal; what creates pain is the stimulation of “nociceptors” present both somatically and viscerally [37].

Nociceptors are primary afferent neurons with a high activation threshold. Acute pain is due to the activation of myelinated nociceptors (mainly Aδ fibers), while chronic pain is generally due to the activation of unmyelinated nociceptors [38][39]. This pain type is distinguished from neuropathic pain by its association with a normally functioning somatosensory nervous system [37][40].

Neuropathic pain is defined as pain caused by a lesion or disease affecting the somatosensory nervous system [41]. It is generally perceived within the territory of innervation of the damaged nerve [35].

Depending on the affected system, it is categorized as peripheral or central: it is peripheral when the lesion and disease affect the peripheral system, and it is central when the central nervous system is affected [34][42].

The somatosensory system includes peripheral receptors and neural pathways through which the central nervous system can detect and process information about the body, such as touch, pressure, vibration, pain, temperature, position, and movement of its parts [43][44]. Therefore, by definition, within the concept of pain, a lesion or disease of the somatosensory system is related to altered pain processing [45][46].

Neuropathic pain can be either spontaneous or evoked, marked by either negative (hypoalgesia, hypoesthesia) or positive sensory signs (hyperalgesia, allodynia) that must be perceived in the territory of innervation of the injured nervous structure [47][48] (Appendix A).

Confirming neuropathic pain often requires demonstrating a nervous system lesion or disease via diagnostic methods such as imaging, biopsies, or neurophysiological tests, with questionnaires serving as supplementary screening tools [49].

The concept of nociplastic pain, a term introduced by the pain research community [35][50], represents the third category [51].

Nociplastic pain is characterized by altered nociception in the absence of clear evidence of either actual or potential tissue damage that would activate peripheral nociceptors, or of any injury to the somatosensory system [52]. Typically, this type of pain presents as multifocal, widespread, and intense, and is often accompanied by a constellation of symptoms including fatigue, sleep disturbances, memory impairment, and mood alterations [36].

Baliki et al. showed changes in brain connectivity in patients with nociplastic pain (chronic back pain and osteoarthritis), demonstrating reduced connectivity of the medial prefrontal cortex and increased connectivity of the insular cortex in proportion to the intensity of pain [53].

This type of pain can manifest itself in isolation, as often occurs in conditions such as fibromyalgia or tension-type headache, or as part of a mixed pain state in combination with nociceptive or neuropathic pain in progress, as might occur in chronic low back pain or chronic orofacial pain [54].

It responds differently to treatments, often showing limited response to anti-inflammatory drugs and opioids [36].

It is crucial to recognize that “neuropathic”, “nociceptive”, and “nociplastic” pain are not specific pathologies in themselves but are used to categorize pain types with potentially shared pathophysiological features [55].

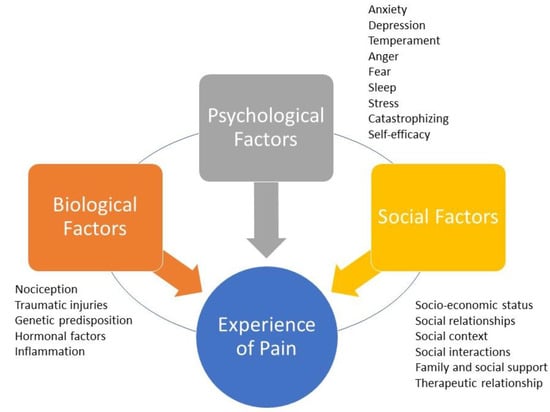

The perception and experience of pain are complex processes that have a multidimensional character, influenced by various factors that do not only involve sensory-discriminative biological processes, but also the interaction of affective, motivational, cognitive, and social factors in a biopsychosocial model, as emphasized by the expansion of the definition by the IASP [31][56]. The model considers the interaction of these factors in the experience of pain [56]. This convergence of diverse elements renders everyone’s pain experience uniquely personal, necessitating a highly individualized approach by healthcare professionals [57][58] (Figure 1).

Figure 1. The biopsychosocial model of pain. The experience of pain is personal because it is mediated by the dynamic, interdependent, and synergistic integration of three factors/domains: biological factors, psychological factors, and social factors. Each domain may have characteristics shared with the others. Biological factors that can negatively affect the perception of pain include traumatic injury, the severity of overall health conditions, and genetic/hormonal predisposition. Psychological factors that can amplify pain include anxiety, depression, sleep disorders, excessive catastrophizing, and low self-efficacy. Social factors that can negatively influence the perception of pain include gender roles, ethnic identity, discrimination, poor family support, and healthcare provider prejudice.

The face and mouth hold a special significance in human physiology and social interaction, serving not just in essential functions like taste, smell, chewing, swallowing, and sensory–motor activities, but also playing a crucial role in interpersonal communication [56][59][60][61]. Consequently, pain in this region gains a multidimensional aspect, often more complex than pain in other body areas [62][63][64]. Facial pain (FP) is commonly defined as pain predominantly occurring below the orbito-meatal line, anterior to the earlobes, and above the neck, with some definitions extending to the forehead, linking certain headaches to orofacial structures [65][66][67][68].

Orofacial pain (OFP) encompasses all structures of the oral cavity [69]. In dental practice, such pain is often associated with dental issues or temporomandibular joint disorders; however, in 30% of cases, dentists may be faced with a type of pain that cannot be attributed to any of the above situations [70][71][72].

Approximately 20% of acute craniofacial pains have the potential to evolve into COFP if not addressed effectively and in good time [73][74]. Dentists play a pivotal role in identifying and managing these conditions, especially when the pain source is not immediately apparent, thus avoiding unnecessary procedures [16][75]. The complexity and often elusive etiology of COFP make diagnosis and treatment challenging, with patients frequently facing delayed diagnosis and intervention, typically 2–3 years post onset, regardless of the pain’s nature [76][77][78].

COFP can be categorized into those with a clear etiology, such as post-herpetic trigeminal neuralgia or post-traumatic neuropathic trigeminal pain [79][80], those associated with chronic diseases like arthritis or diabetes, and a significant number of idiopathic cases where the cause remains unidentified, including conditions like burning mouth syndrome (BMS), persistent idiopathic facial pain (PIFP), or persistent idiopathic dentoalveolar pain (PIDP) [81]. Consequently, COFP is classified as primary when idiopathic and secondary when linked to an identifiable pathological process [73][82]. The impact of COFP extends beyond physical discomfort, often correlating with mood disorders, sleep disturbances, cognitive impairments, and a substantial reduction in quality of life [3][83][84].

Symptomatically, COFP shares common features with other pain types, such as neuropathic characteristics, including spontaneous, intermittent, lancinating, or burning sensations, alongside both positive and negative sensory symptoms [33][85] (Appendix A).

The prevalence of OFP varies, with estimates ranging from 16.1% to 33.2%, and a more realistic figure seems to hover around 25% [86]. Within this spectrum, COFP accounts for about 10%, positioning it among the most common types of chronic pain, after low back, neck, and knee pain [1]. Recent studies indicate an incidence rate of COFP at approximately 38.7 per 100,000 person-years. It is more prevalent in women and tends to increase with age [87].

The majority of COFP cases are linked to musculoskeletal disorders, particularly temporomandibular disorders (TMDs), which affect an average of 4.6% of the general population, with a higher incidence in women (6.3%) compared to men (2.8%) [88].

Another highly prevalent form of COFP is BMS [89].

The worldwide prevalence of BMS is estimated at 1.73% in the general population, which notably increases to 7.72% among dental patients, as detailed in a 2021 meta-analysis conducted by Wu et al. [90]. This extensive study included both clinical and population-based research, offering a comprehensive view. However, the exact prevalence rates vary due to differences in population demographics, geographic regions, and diagnostic criteria used. In terms of geographic distribution, BMS prevalence is higher in Europe (5.58%) and North America (1.10%), compared to Asia (1.05%), within the general population. This trend reverses in clinical settings, with Asia reporting a higher prevalence (8.96%) than South America (6.05%) and Europe (6.46%) [90]. Such variations underscore the significant impact of geographic factors on BMS occurrence. A gender-specific analysis of the data reveals a more pronounced prevalence of BMS in females (1.15%) than in males (0.38%) within the general population, indicating a ratio of approximately 3:1 [91]. This notable gender disparity in BMS prevalence may be linked to physiological and behavioral factors specific to each gender [92].

Trigeminal neuralgia (TN) is relatively rare, with a prevalence ranging from 0.03% to 0.3% in the general population, and an incidence of approximately 1 case per 70,000 to 100,000 individuals annually [93][94]. The likelihood of developing TN increases with age and the presence of certain medical conditions, such as migraines [95]. Notably, TN is 15–20 times more prevalent in individuals with multiple sclerosis, where its prevalence ranges between 1.1% and 6.3% [96].

PIFP is also rare, occurring in about 0.03% of the population, with an incidence rate of 4.4 per 100,000 person-years. PIFP predominantly affects females, typically manifesting around the age of 40 [97].

2. Classification System in Medicine

An ideal classification system in medicine is pivotal, serving as a comprehensive, biologically plausible, clinically useful, and reliable framework. In the realm of OFP, such a system is indispensable for accurate disease identification, effective treatment planning, and enhanced patient understanding and acceptance of their condition.

Classification in medicine organizes pathologies into categories based on specific criteria [98]. For OFP, these criteria often stem from etiology, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and management [70]. Clinicians rely on this classification for precise disease identification and treatment strategies. Patients benefit from a clear diagnosis framed within a globally recognized system, aiding in their understanding and acceptance of the disease. Moreover, for research purposes, classification is crucial as it ensures consistent diagnostic criteria are applied across studies, whether in pharmacological trials or pathophysiological investigations.

According to Fillingim et al. [99], an ideal classification system should be:

-

exhaustive (including all clinical diseases or disorders within the field of interest);

-

biologically plausible (symptoms and signs should correspond to known biological processes) and mutually exclusive (there should be no overlap between disease entities due to common symptoms);

-

clinically useful (so that it can be used to aid in treatment and prognosis);

-

reliable (applicable consistently and reproducibly among clinicians);

-

simple for practical use.

However, most current OFP classification systems suffer from deficits in at least one of these qualities.

The variability in definitions across different classifications, drafted by independent clinician groups, further complicates this issue.

Although there is no consensus yet regarding a universal and unique OFP classification, the latest ICOP 2020 classification [69] seems to encompass most of Fillingim et al.’s requirements [99].

Other notable systems include:

The ongoing updates to these classifications, readily available online, reflect the scientific community’s commitment to enhancing the understanding of these pathologies. This process exemplifies the dynamic and evolving nature of medical knowledge, driven by continual research and clinical findings. As new insights emerge, classification systems are systematically refined and expanded, ensuring they remain current and applicable. This iterative approach is integral to advancing medical science and improving diagnostic accuracy, ultimately leading to better patient outcomes and more effective treatments.

The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd edition (ICHD-3) beta version.

Since its inaugural publication in 1988 by the International Headache Society (IHS), the ICHD has undergone significant revisions, with major updates in 2004, 2013 (ICHD-3), in 2018 (ICHD-3 beta version), and in 2020 [65][100]. This taxonomic classification system, primarily focused on headache-related disorders and painful craniofacial conditions, is organized into a three-part system. Parts I and II categorize primary and secondary headaches across 12 main groups. Part III addresses painful cranial neuropathies and other facial pain conditions, particularly those related to the trigeminal nerve [101].

This part has two distinct sections, one for primary painful craniofacial neuralgias and facial pain and the other for unclassified or unspecified headaches. A reference to OFP conditions also appears in Part II of the ICHD-3, dedicated to secondary headaches, which occur when a primary headache worsens in close temporal relationship with a causative OFP condition. Therefore, the ICHD-3 recognizes that some disorders arising from dental, maxillary, maxillary–sinus, eye, ear, and nose elements can cause headaches. However, despite its comprehensive structure, ICHD-3 falls short in encompassing all clinical phenotypes of OFP and does not adequately consider biopsychosocial and behavioral factors [101][102].

The hierarchical nature of the ICHD-3 allows for varying levels of diagnostic detail, adaptable to different clinical settings in which clinicians may decide the necessary level of diagnosis based on the type of practice. Therefore, coding can range from one digit up to five depending on the detail of the criteria used in the diagnosis. This flexibility is crucial for accurately diagnosing and coding over 200 headache-related disorders categorized in 12 main headache categories. The ultimate goal is to align this coding system with the WHO’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11) [14][31].

In oral medicine, the most frequently referenced category within Part III is Category 13, dealing specifically with OFP conditions [103].

Parallel to the ICHD’s development, the IASP has collaborated with the WHO to integrate a systematic classification of chronic pain into the ICD-11.

Every update or recent development related to the ICHD or ICD-11 since 2018 is available on-line.

This integration represents a significant step towards a more comprehensive understanding of chronic pain conditions, including OFP, and emphasizes the need for a multidimensional approach to diagnosis and treatment.

The International Classification of Diseases 11th Revision (ICD-11).

The 11th Revision of the ICD-11 [12], published by the WHO in June 2018, represents a significant evolution in the global standard for health data classification. Its international and multilingual taxonomy is used for collecting and reporting data on health services (e.g., statistics on morbidity and mortality, quality and safety, health costs, and clinical research).

This latest revision, which has been the international standard for coding since 2022, offers enhanced features for research applicability, clinical detail encoding, and modernized scientific content. One of the pivotal advancements in ICD-11, as highlighted by Scholz et al. [35], is its refined approach to chronic pain, now recognized both as a symptom and as a distinct disease entity, complete with a supportive coding framework.

A groundbreaking feature of ICD-11 is the concept of “multiple parenting”, which allows diagnostic entities to be classified under more than one category. This flexibility overcomes previous limitations where diseases could only be classified singularly by etiology or site [14]. For instance, “Chemotherapy-induced chronic pain” can be categorized both under “Chronic cancer pain” (etiology) and “Chronic neuropathic pain” (mechanism). This multifaceted approach aligns more closely with the interdisciplinary nature of medical practice, bridging gaps between specialties such as oncology and neurology.

The ICD-11 pain classification introduces nine main diagnostic categories [14].

Specifically, neuropathic pain conditions are divided into two major categories:

-

Chronic central neuropathic pain (MG 30.50);

-

Chronic peripheral neuropathic pain (MG 30.51).

Orofacial pain in the ICD-11 is recognized as a significant medical entity, reflecting advancements in understanding pain as a complex, multidimensional experience [104].

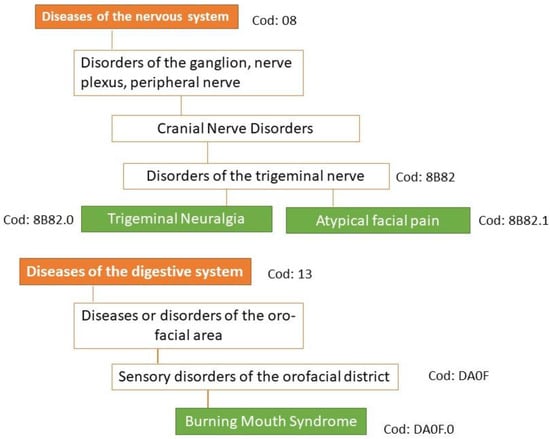

Notably, OFP is categorized under secondary chronic headaches (code MG 30.62) with specific codes assigned to different conditions such as NT, PIFP, and BMS [14][105].

Specific codes for orofacial pain conditions:

-

NT: 8B82.0 under trigeminal disorders (Foundation ID in the ICD-11 browser: 1803581281);

-

PIFP: 8B82.1 under trigeminal disorders (Foundation ID in the ICD-11 browser: 248232693);

-

BMS: DA0F.0: sensory disturbances involving the orofacial region (Foundation ID in the ICD-11 browser: 618998878) (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Classification of the three main types of orofacial pain according to ICD-11. Under the new concept of multiple parenting in ICD-11, each entity can be assigned to other divisions of the classification of chronic pain. In ICD-11, persistent idiopathic facial pain is referred to as atypical facial pain.

See website https://icd.who.int/en accessed on 5 November 2023 for the complete classification of ICD-11.

The ICOP 2020 marks a significant evolution in the understanding and classification of OFP [69]. This system, modeled after the ICHD-3, offers a nuanced approach to diagnosing OFP based on symptomatology and suspected pathophysiology, prioritizing the disorder’s characteristics over its location. This novel approach broadens the diagnostic criteria and fosters a more comprehensive understanding of various OFP forms improving a proper diagnosis and management.

The hierarchical classification system of the ICOP 2020 enables a granular diagnosis, ranging from a broad categorization (first digit) to highly specific classifications (up to the seventh digit) [69]. This level of detail adapts to different clinical contexts, with general medicine often utilizing first or second digit diagnoses, while specialist practices may require more detailed coding.

Unlike ICHD-3, primary and secondary OFP are included in the same group in separate subgroups because, according to experts, the strict structure of the ICHD criteria, using Criterion A to describe the pain, Criterion B to identify the presumed cause, and Criterion C to establish evidence of causality, is not easily applicable to OFP.

In cases where patients present with multiple types of pain, diagnoses should be prioritized based on the patient’s experience of suffering and disability, also including the longitudinal history of pain (how and when did the pain start?), family history, medication effect, relationship with menstrual cycle, age, sex, etc.

For a definitive OFP diagnosis, patients must experience a minimum number of attacks or days with pain, as specified in the detailed criteria for each type or subtype of OFP. Different OFPs must meet a series of other requirements described in the criteria under separate letter headings, i.e., A, B, C, etc. Some letter headings are monothematic, expressing a single requirement. Other letter headings are polythematic and require, for example, two of the four listed characteristics. This structure is common in the ICHD-3 [65].

The diagnostic criteria in this classification do not include the evaluation of the severity and frequency of painful attacks, which should be evaluated and specified [106][107].

Another innovative feature of this classification is the introduction of the “psychosocial assessment of patients with OFP”. This approach integrates psychometric testing for a holistic evaluation of the patient, acknowledging the significant role of psychological factors in pain perception and management [69].

References

- Mills, S.E.E.; Nicolson, K.P.; Smith, B.H. Chronic Pain: A Review of Its Epidemiology and Associated Factors in Population-Based Studies. Br. J. Anaesth. 2019, 123, e273–e283.

- Elliott, A.M.; Smith, B.H.; Penny, K.I.; Smith, W.C.; Chambers, W.A. The Epidemiology of Chronic Pain in the Community. Lancet 1999, 354, 1248–1252.

- Vartiainen, P.; Roine, R.P.; Kalso, E.; Heiskanen, T. Worse Health-Related Quality of Life, Impaired Functioning and Psychiatric Comorbidities Are Associated with Excess Mortality in Patients with Severe Chronic Pain. Eur. J. Pain 2022, 26, 1135–1146.

- Hadi, M.A.; McHugh, G.A.; Closs, S.J. Impact of Chronic Pain on Patients’ Quality of Life: A Comparative Mixed-Methods Study. J. Patient Exp. 2019, 6, 133–141.

- Rayner, L.; Hotopf, M.; Petkova, H.; Matcham, F.; Simpson, A.; McCracken, L.M. Depression in Patients with Chronic Pain Attending a Specialised Pain Treatment Centre: Prevalence and Impact on Health Care Costs. Pain 2016, 157, 1472–1479.

- Kawai, K.; Kawai, A.T.; Wollan, P.; Yawn, B.P. Adverse Impacts of Chronic Pain on Health-Related Quality of Life, Work Productivity, Depression and Anxiety in a Community-Based Study. Fam. Pract. 2017, 34, 656–661.

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Advancing Pain Research, Care, and Education. Relieving Pain in America: A Blueprint for Transforming Prevention, Care, Education, and Research. In The National Academies Collection: Reports Funded by National Institutes of Health; National Academies Press (US): Washington, DC, USA, 2011.

- Koesling, D.; Bozzaro, C. Chronic Pain Patients’ Need for Recognition and Their Current Struggle. Med. Health Care Philos. 2021, 24, 563–572.

- Varenna, M.; Crotti, C.; Ughi, N.; Zucchi, F.; Caporali, R. Determinants of Diagnostic Delay in Complex Regional Pain Syndrome Type 1: An Observational Study of 180 Consecutive New Cases. J. Clin. Rheumatol. 2021, 27, e491–e495.

- Nicola, M.; Correia, H.; Ditchburn, G.; Drummond, P.D. Defining Pain-Validation: The Importance of Validation in Reducing the Stresses of Chronic Pain. Front. Pain Res. 2022, 3, 884335.

- Chmieliauskaite, M.; Stelson, E.A.; Epstein, J.B.; Klasser, G.D.; Farag, A.; Carey, B.; Albuquerque, R.; Mejia, L.; Ariyawardana, A.; Nasri-Heir, C.; et al. Consensus Agreement to Rename Burning Mouth Syndrome and Improve ICD-11 Disease Criteria: An International Delphi Study. Pain 2021, 162, 2548–2557.

- ICD-11 for Mortality and Morbidity Statistics. Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse/11/2018/mms/en (accessed on 11 November 2023).

- National Pain Strategy Overview|IPRCC. Available online: https://www.iprcc.nih.gov/national-pain-strategy-overview (accessed on 13 November 2023).

- The Lancet. ICD-11. Lancet 2019, 393, 2275.

- Heath, L.; Philip, A. Chronic Pain Care: Time for Excellence. Fam. Med. Community Health 2020, 8, e000285.

- Costa, Y.M.; De Koninck, B.P.; Elsaraj, S.M.; Exposto, F.G.; Herrero Babiloni, A.; Kapos, F.P.; Sharma, S.; Shimada, A. Orofacial Pain Education in Dentistry: A Path to Improving Patient Care and Reducing the Population Burden of Chronic Pain. J. Dent. Educ. 2021, 85, 349–358.

- Kappesser, J. The Facial Expression of Pain in Humans Considered from a Social Perspective. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2019, 374, 20190284.

- Häggman-Henrikson, B.; Liv, P.; Ilgunas, A.; Visscher, C.M.; Lobbezoo, F.; Durham, J.; Lövgren, A. Increasing Gender Differences in the Prevalence and Chronification of Orofacial Pain in the Population. Pain 2020, 161, 1768–1775.

- Benoliel, R.; Pertes, R.A.; Eliav, E. Chapter 17—OROFACIAL PAIN. In Current Therapy in Pain; Smith, H.S., Ed.; W.B. Saunders: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2009.

- Taheri, J.B.; Anbari, F.; Sani, S.K.; Mirmoezi, S.M.; Khalighi, H.R. A 10-Year Overview of Chronic Orofacial Pain in Patients at an Oral Medicine Center in Iran. J. Dent. Anesth. Pain. Med. 2022, 22, 289–294.

- Kumar, A.; Brennan, M.T. Differential Diagnosis of Orofacial Pain and Temporomandibular Disorder. Dent. Clin. North Am. 2013, 57, 419–428.

- Peng, K.-P.; Oppermann, T. Orofacial Pain Disorders: An Overview and Diagnostic Approach. Cephalalgia Rep. 2022, 5, 25158163221097349.

- Adamo, D.; Spagnuolo, G. Burning Mouth Syndrome: An Overview and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 20, 682.

- Meints, S.M.; Edwards, R.R. Evaluating Psychosocial Contributions to Chronic Pain Outcomes. Prog. Neuropsychopharmacol. Biol. Psychiatry 2018, 87, 168–182.

- Párraga, J.P.; Castellanos, A. A Manifesto in Defense of Pain Complexity: A Critical Review of Essential Insights in Pain Neuroscience. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 7080.

- Jensen, M.P.; Moore, M.R.; Bockow, T.B.; Ehde, D.M.; Engel, J.M. Psychosocial Factors and Adjustment to Chronic Pain in Persons with Physical Disabilities: A Systematic Review. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil. 2011, 92, 146–160.

- Prego-Domínguez, J.; Skillgate, E.; Orsini, N.; Takkouche, B. Social Factors and Chronic Pain: The Modifying Effect of Sex in the Stockholm Public Health Cohort Study. Rheumatology 2022, 61, 1802–1809.

- Borsook, D.; Kalso, E. Transforming Pain Medicine: Adapting to Science and Society. Eur. J. Pain 2013, 17, 1109–1125.

- Ablin, J.N.; Buskila, D. Personalized Treatment of Pain. Curr. Rheumatol. Rep. 2013, 15, 298.

- Hui, D.; Bruera, E. A Personalized Approach to Assessing and Managing Pain in Patients with Cancer. J. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 32, 1640–1646.

- Scholz, J.; Finnerup, N.B.; Attal, N.; Aziz, Q.; Baron, R.; Bennett, M.I.; Benoliel, R.; Cohen, M.; Cruccu, G.; Davis, K.D.; et al. The IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for ICD-11: Chronic Neuropathic Pain. Pain 2019, 160, 53–59.

- Cohen, M.; Quintner, J.; van Rysewyk, S. Reconsidering the International Association for the Study of Pain Definition of Pain. Pain. Rep. 2018, 3, e634.

- Raja, S.N.; Carr, D.B.; Cohen, M.; Finnerup, N.B.; Flor, H.; Gibson, S.; Keefe, F.; Mogil, J.S.; Ringkamp, M.; Sluka, K.A.; et al. The Revised IASP Definition of Pain: Concepts, Challenges, and Compromises. Pain 2020, 161, 1976–1982.

- Treede, R.-D.; Rief, W.; Barke, A.; Aziz, Q.; Bennett, M.I.; Benoliel, R.; Cohen, M.; Evers, S.; Finnerup, N.B.; First, M.B.; et al. Chronic Pain as a Symptom or a Disease: The IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11). Pain 2019, 160, 19–27.

- Nicholas, M.; Vlaeyen, J.W.S.; Rief, W.; Barke, A.; Aziz, Q.; Benoliel, R.; Cohen, M.; Evers, S.; Giamberardino, M.A.; Goebel, A.; et al. IASP Taskforce for the Classification of Chronic Pain. The IASP classification of chronic pain for ICD-11: Chronic primary pain. Pain. 2019, 160, 28–37.

- Fitzcharles, M.-A.; Cohen, S.P.; Clauw, D.J.; Littlejohn, G.; Usui, C.; Häuser, W. Nociplastic Pain: Towards an Understanding of Prevalent Pain Conditions. Lancet 2021, 397, 2098–2110.

- St John Smith, E. Advances in Understanding Nociception and Neuropathic Pain. J. Neurol. 2018, 265, 231–238.

- Dubin, A.E.; Patapoutian, A. Nociceptors: The Sensors of the Pain Pathway. J. Clin. Investig. 2010, 120, 3760–3772.

- Eilers, H.; Schumacher, M.A. Mechanosensitivity of Primary Afferent Nociceptors in the Pain Pathway. In Mechanosensitivity in Cells and Tissues; Kamkin, A., Kiseleva, I., Eds.; Academia: Moscow, Russia, 2005.

- Tajti, J.; Szok, D.; Csáti, A.; Szabó, Á.; Tanaka, M.; Vécsei, L. Exploring Novel Therapeutic Targets in the Common Pathogenic Factors in Migraine and Neuropathic Pain. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 4114.

- Costigan, M.; Scholz, J.; Woolf, C.J. Neuropathic Pain. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2009, 32, 1–32.

- Nie, L.; Jiang, L.; Quinn, J.P.; Grubb, B.D.; Wang, M. TRPA1-Mediated Src Family Kinases Activity Facilitates Cortical Spreading Depression Susceptibility and Trigeminovascular System Sensitization. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 12273.

- Raju, H.; Tadi, P. Neuroanatomy, Somatosensory Cortex. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023.

- Spekker, E.; Tanaka, M.; Szabó, Á.; Vécsei, L. Neurogenic Inflammation: The Participant in Migraine and Recent Advancements in Translational Research. Biomedicines 2022, 10, 76.

- Finnerup, N.B.; Haroutounian, S.; Kamerman, P.; Baron, R.; Bennett, D.L.H.; Bouhassira, D.; Cruccu, G.; Freeman, R.; Hansson, P.; Nurmikko, T.; et al. Neuropathic Pain: An Updated Grading System for Research and Clinical Practice. Pain 2016, 157, 1599–1606.

- Tanaka, M.; Török, N.; Tóth, F.; Szabó, Á.; Vécsei, L. Co-Players in Chronic Pain: Neuroinflammation and the Tryptophan-Kynurenine Metabolic Pathway. Biomedicines 2021, 9, 897.

- Baron, R. Neuropathic Pain: A Clinical Perspective. In Handbook of Experimental Pharmacology; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009; pp. 3–30.

- Toraman, A.; Toraman, E.; Özkaraca, M.; Budak, H. Evaluated Periodontal Tissues and Oxidative Stress in Rats with Neuropathic Pain-like Behavior. Mol. Biol. Rep. 2023, 50, 9315–9322.

- Attal, N.; Bouhassira, D.; Baron, R. Diagnosis and Assessment of Neuropathic Pain through Questionnaires. Lancet Neurol. 2018, 17, 456–466.

- Kosek, E.; Cohen, M.; Baron, R.; Gebhart, G.F.; Mico, J.-A.; Rice, A.S.C.; Rief, W.; Sluka, A.K. Do We Need a Third Mechanistic Descriptor for Chronic Pain States? Pain 2016, 157, 1382–1386.

- Alcántara Montero, A. Importance of Nociplastic Pain in Patients with Rheumatic Diseases. Clinics 2023, 78, 100309.

- Kosek, E.; Clauw, D.; Nijs, J.; Baron, R.; Gilron, I.; Harris, R.E.; Mico, J.-A.; Rice, A.S.C.; Sterling, M. Chronic Nociplastic Pain Affecting the Musculoskeletal System: Clinical Criteria and Grading System. Pain 2021, 162, 2629.

- Baliki, M.N.; Mansour, A.R.; Baria, A.T.; Apkarian, A.V. Functional Reorganization of the Default Mode Network across Chronic Pain Conditions. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e106133.

- Woolf, C.J.; Mannion, R.J. Neuropathic Pain: Aetiology, Symptoms, Mechanisms, and Management. Lancet 1999, 353, 1959–1964.

- Bonezzi, C.; Fornasari, D.; Cricelli, C.; Magni, A.; Ventriglia, G. Not All Pain Is Created Equal: Basic Definitions and Diagnostic Work-Up. Pain Ther. 2020, 9, 1–15.

- Gatchel, R.J.; Peng, Y.B.; Peters, M.L.; Fuchs, P.N.; Turk, D.C. The Biopsychosocial Approach to Chronic Pain: Scientific Advances and Future Directions. Psychol. Bull. 2007, 133, 581–624.

- Gevers-Montoro, C.; Liew, B.X.W.; Deldar, Z.; Conesa-Buendia, F.M.; Ortega-De Mues, A.; Falla, D.; Khatibi, A. A Network Analysis on Biopsychosocial Factors and Pain-Related Outcomes Assessed during a COVID-19 Lockdown. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 4399.

- Johnson, K.B.; Wei, W.; Weeraratne, D.; Frisse, M.E.; Misulis, K.; Rhee, K.; Zhao, J.; Snowdon, J.L. Precision Medicine, AI, and the Future of Personalized Health Care. Clin. Transl. Sci. 2021, 14, 86–93.

- Abramson, L.; Petranker, R.; Marom, I.; Aviezer, H. Social Interaction Context Shapes Emotion Recognition through Body Language, Not Facial Expressions. Emotion 2021, 21, 557–568.

- Frith, C. Role of Facial Expressions in Social Interactions. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. B Biol. Sci. 2009, 364, 3453–3458.

- Langeslag, S.J.; Gootjes, L.; van Strien, J.W. The Effect of Mouth Opening in Emotional Faces on Subjective Experience and the Early Posterior Negativity Amplitude. Brain Cogn. 2018, 127, 51–59.

- Hargreaves, K.M. CONGRESS Orofacial Pain. Pain 2011, 152, S25–S32.

- Zimet, G.D.; Dahlem, N.W.; Zimet, S.G.; Farley, G.K. The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. J. Personal. Assess. 1988, 52, 30–41.

- Canfora, F.; Calabria, E.; Pecoraro, G.; D′Aniello, L.; Aria, M.; Marenzi, G.; Sammartino, P.; Mignogna, M.D.; Adamo, D. The Use of Self-Report Questionnaires in an Analysis of the Multidimensional Aspects of Pain and a Correlation with the Psychological Profile and Quality of Life in Patients with Burning Mouth Syndrome: A Case-Control Study. J. Oral Rehabil. 2022, 49, 890–914.

- Gobel, H.; The International Classification of Headache Disorders. ICHD-3. Available online: https://ichd-3.org/ (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- Weiss, A.L.; Ehrhardt, K.P.; Tolba, R. Atypical Facial Pain: A Comprehensive, Evidence-Based Review. Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2017, 21, 8.

- Ziegeler, C.; Beikler, T.; Gosau, M.; May, A. Idiopathic Facial Pain Syndromes–An Overview and Clinical Implications. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2021, 118, 81–87.

- Van Deun, L.; de Witte, M.; Goessens, T.; Halewyck, S.; Ketelaer, M.-C.; Matic, M.; Moens, M.; Vaes, P.; Van Lint, M.; Versijpt, J. Facial Pain: A Comprehensive Review and Proposal for a Pragmatic Diagnostic Approach. Eur. Neurol. 2020, 83, 5–16.

- International Classification of Orofacial Pain, 1st Edition (ICOP). Cephalalgia 2020, 40, 129–221.

- Labanca, M.; Gianò, M.; Franco, C.; Rezzani, R. Orofacial Pain and Dentistry Management: Guidelines for a More Comprehensive Evidence-Based Approach. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 2854.

- Crandall, J.A. An Introduction to Orofacial Pain. Dent. Clin. North Am. 2018, 62, 511–523.

- Ghurye, S.; McMillan, R. Orofacial Pain—An Update on Diagnosis and Management. Br. Dent. J. 2017, 223, 639–647.

- Sessle, B.J. Chronic Orofacial Pain: Models, Mechanisms, and Genetic and Related Environmental Influences. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7112.

- Ananthan, S.; Benoliel, R. Chronic Orofacial Pain. J. Neural Transm. 2020, 127, 575–588.

- Hadlaq, E.M.; Khan, H.; Mubayrik, A.B.; Almuflehi, N.S.; Mawardi, H. Dentists’ Knowledge of Chronic Orofacial Pain. Niger. J. Clin. Pract. 2019, 22, 1365–1371.

- Tomoyasu, Y.; Higuchi, H.; Mori, M.; Takaya, K.; Honda, Y.; Yamane, A.; Yabuki, A.; Hayashi, T.; Ishii-Maruyama, M.; Jinzenji, A.; et al. Chronic Orofacial Pain in Dental Patients: Retrospective Investigation over 12 Years. Acta Med. Okayama 2014, 68, 269–275.

- Sarlani, E.; Balciunas, B.A.; Grace, E.G. Orofacial Pain—Part I: Assessment and Management of Musculoskeletal and Neuropathic Causes. AACN Clin. Issues 2005, 16, 333–346.

- Adamo, D.; Mignogna, M.D.; Wang, X.-Q.; Femminella, G.D. Editorial: Chronic Pain in Neuropsychiatric Diseases. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2023, 17, 1213217.

- Veerapaneni, K.D.; Kapoor, N.; Veerapaneni, P.; Nalleballe, K. Trigeminal Neuropathy. In StatPearls; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2023.

- Fisher, R.; Clarkson, E. Medication Management of Neuropathic Pain Disorders. Dent. Clin. North Am. 2024, 68, 121–131.

- Heir, G.M.; Ananthan, S.; Kalladka, M.; Kuchukulla, M.; Renton, T. Persistent Idiopathic Dentoalveolar Pain: Is It a Central Pain Disorder? Dent. Clin. North Am. 2023, 67, 71–83.

- Ayoub, L.J.; Seminowicz, D.A.; Moayedi, M. A Meta-Analytic Study of Experimental and Chronic Orofacial Pain Excluding Headache Disorders. NeuroImage Clin. 2018, 20, 901–912.

- Lovette, B.C.; Bannon, S.M.; Spyropoulos, D.C.; Vranceanu, A.-M.; Greenberg, J. “I Still Suffer Every Second of Every Day”: A Qualitative Analysis of the Challenges of Living with Chronic Orofacial Pain. J. Pain Res. 2022, 15, 2139–2148.

- Vickers, E.R.; Boocock, H. Chronic Orofacial Pain Is Associated with Psychological Morbidity and Negative Personality Changes: A Comparison to the General Population. Aust. Dent. J. 2005, 50, 21–30.

- Foreman, P.A. Chronic Orofacial Pain: A Clinical Challenge. N. Z. Dent. J. 2008, 104, 44–48.

- Setty, S.; David, J. Classification and Epidemiology of Orofacial Pain. In Orofacial Pain: A Clinician’s Guide; Vadivelu, N., Vadivelu, A., Kaye, A.D., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2014.

- Derafshi, R.; Rezazadeh, F.; Ghapanchi, J.; Basandeh Sharif, D.; Farzin, M. Prevalence of Chronic Orofacial Pain in Elderly Patients Referred to Shiraz Dental School From 2005 to 2017. Anesth. Pain Med. 2019, 9, e91182.

- Isong, U.; Gansky, S.A.; Plesh, O. Temporomandibular Joint and Muscle Disorder-Type Pain in US Adults: The National Health Interview Survey. J. Orofac. Pain 2008, 22, 317–322.

- Khawaja, S.N.; Alaswaiti, O.F.; Scrivani, S.J. Burning Mouth Syndrome. Dent. Clin. North. Am. 2023, 67, 49–60.

- Wu, S.; Zhang, W.; Yan, J.; Noma, N.; Young, A.; Yan, Z. Worldwide Prevalence Estimates of Burning Mouth Syndrome: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Oral Dis. 2021, 28, 1431–1440.

- Kohorst, J.J.; Bruce, A.J.; Torgerson, R.R.; Schenck, L.A.; Davis, M.D.P. The Prevalence of Burning Mouth Syndrome: A Population-Based Study. Br. J. Dermatol. 2015, 172, 1654–1656.

- Adamo, D.; Canfora, F.; Calabria, E.; Coppola, N.; Sansone, M.; Spagnuolo, G.; Pecoraro, G.; Aria, M.; D’Aniello, L.; Mignogna, M.D.; et al. Burning Mouth Syndrome and Hypertension: Prevalence, Gender Differences and Association with Pain and Psycho-Social Characteristics-A Case Control Study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2040.

- Araya, E.I.; Claudino, R.F.; Piovesan, E.J.; Chichorro, J.G. Trigeminal Neuralgia: Basic and Clinical Aspects. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2020, 18, 109–119.

- Khawaja, S.N.; Scrivani, S.J. Trigeminal Neuralgia. Dent. Clin. North Am. 2023, 67, 99–115.

- Mungoven, T.J.; Meylakh, N.; Marciszewski, K.K.; Macefield, V.G.; Macey, P.M.; Henderson, L.A. Microstructural Changes in the Trigeminal Nerve of Patients with Episodic Migraine Assessed Using Magnetic Resonance Imaging. J. Headache Pain 2020, 21, 59.

- Laakso, S.M.; Hekali, O.; Kurdo, G.; Martola, J.; Sairanen, T.; Atula, S. Trigeminal Neuralgia in Multiple Sclerosis: Prevalence and Association with Demyelination. Acta Neurol. Scand. 2020, 142, 139–144.

- Schweiger, V.; Nocini, R.; De Santis, D.; Procacci, P.; Zanette, G.; Secchettin, E.; Del Balzo, G.; Fior, A.; Martini, A.; Nizzero, M.; et al. Persistent Idiopathic Facial Pain (PIFP) in Patients Referred to a Multidisciplinary Centre in Italy: A Retrospective Observational Study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 3821.

- Haendel, M.A.; Chute, C.G.; Robinson, P.N. Classification, Ontology, and Precision Medicine. N. Engl. J. Med. 2018, 379, 1452–1462.

- Fillingim, R.B.; Bruehl, S.; Dworkin, R.H.; Dworkin, S.F.; Loeser, J.D.; Turk, D.C.; Widerstrom-Noga, E.; Arnold, L.; Bennett, R.; Edwards, R.R.; et al. The ACTTION-American Pain Society Pain Taxonomy (AAPT): An Evidence-Based and Multidimensional Approach to Classifying Chronic Pain Conditions. J. Pain 2014, 15, 241–249.

- Headache Classification Committee of the International Headache Society (IHS). The International Classification of Headache Disorders, 3rd Edition (Beta Version). Cephalalgia 2013, 33, 629–808.

- Manzoni, G.C.; Grisendi, I.; Torelli, P. ICHD-3: What Changes Do We Need Regarding Migraine? Curr. Pain Headache Rep. 2011, 15, 170–176.

- Göbel, C.H.; Karstedt, S.C.; Münte, T.F.; Göbel, H.; Wolfrum, S.; Lebedeva, E.R.; Olesen, J.; Royl, G. ICHD-3 Is Significantly More Specific than ICHD-3 Beta for Diagnosis of Migraine with Aura and with Typical Aura. J. Headache Pain 2020, 21, 2.

- Gobel, H.; 13.11 Burning Mouth Syndrome (BMS). ICHD-3. Available online: https://ichd-3.org/13-painful-cranial-neuropathies-and-other-facial-pains/13-11-persistent-idiopathic-facial-pain-pifp/ (accessed on 9 February 2022).

- Benoliel, R.; Svensson, P.; Evers, S.; Wang, S.-J.; Barke, A.; Korwisi, B.; Rief, W.; Treede, R.-D. IASP Taskforce for the Classification of Chronic Pain. The IASP Classification of Chronic Pain for ICD-11: Chronic Secondary Headache or Orofacial Pain. Pain 2019, 160, 60–68.

- Peng, K.-P.; Benoliel, R.; May, A. A Review of Current Perspectives on Facial Presentations of Primary Headaches. J. Pain Res. 2022, 15, 1613–1621.

- Üstün Özek, S. A Study on the Correlation between Pain Frequency and Severity and Vitamin B12 Levels in Episodic and Chronic Migraine. Arq. Neuropsiquiatr. 2022, 80, 586–592.

- Akgün, N.; Acıman Demirel, E.; Açıkgöz, M.; Çelebi, U.; Köktürk, F.; Atasoy, H.T. The Effect of Weather Variables on the Severity, Duration, and Frequency of Headache Attacks in the Cases of Episodic Migraine and Episodic Tension-Type Headache. Turk. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 51, 1406–1412.

More

Information

Subjects:

Neurosciences

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

504

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

14 Dec 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No