| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Qilei Tong | -- | 2822 | 2023-12-11 10:02:19 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | Meta information modification | 2822 | 2023-12-11 10:15:52 | | |

Video Upload Options

Nanofluid-enhanced oil recovery (EOR) technology is an innovative approach to enhancing oil production in oilfields. It entails the dispersion of nanoparticles within a fluid, strategically utilizing the distinctive properties of these nanoparticles (NPs) to engage with reservoir rocks or crude oil, resulting in a significant enhancement of the oil recovery rate.

1. Introduction

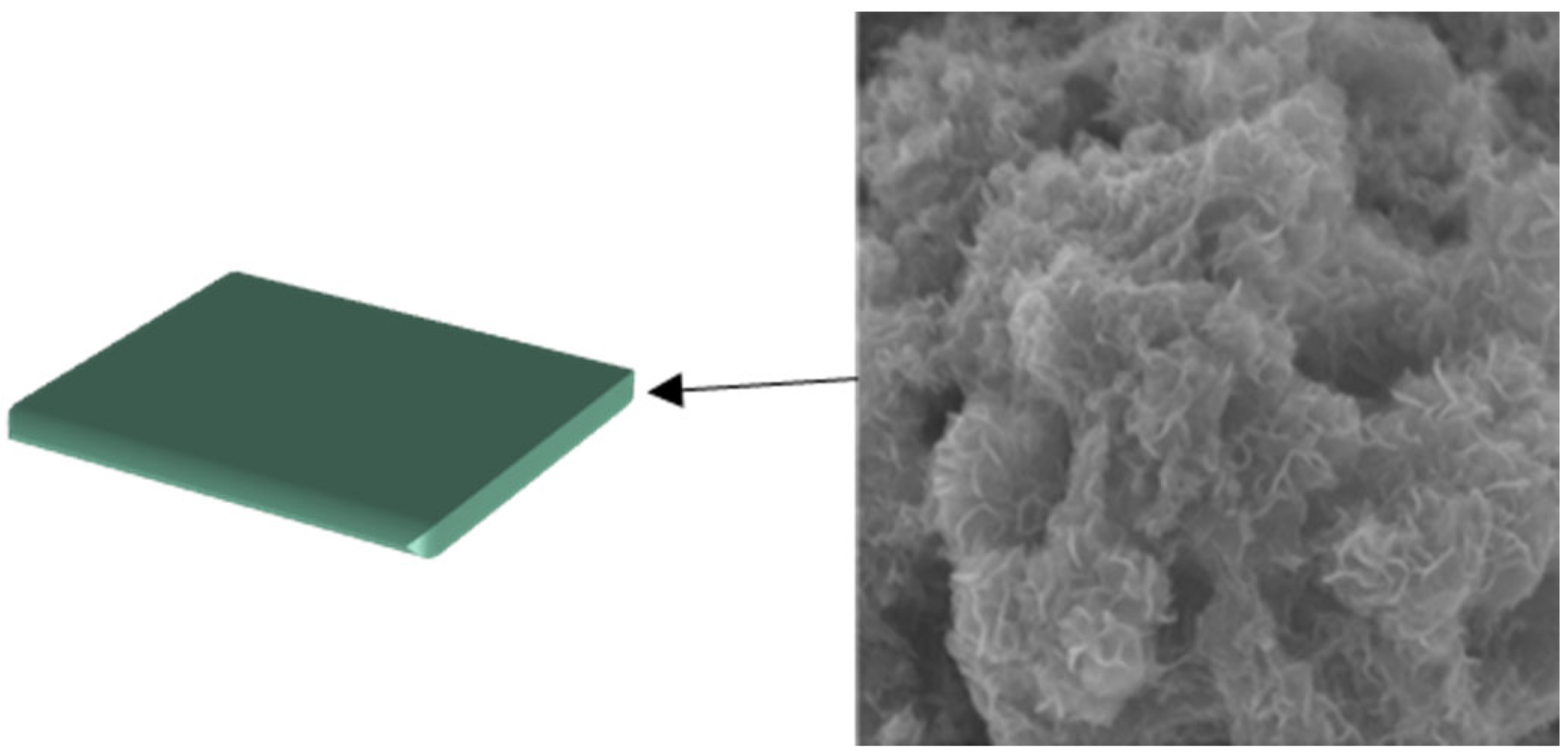

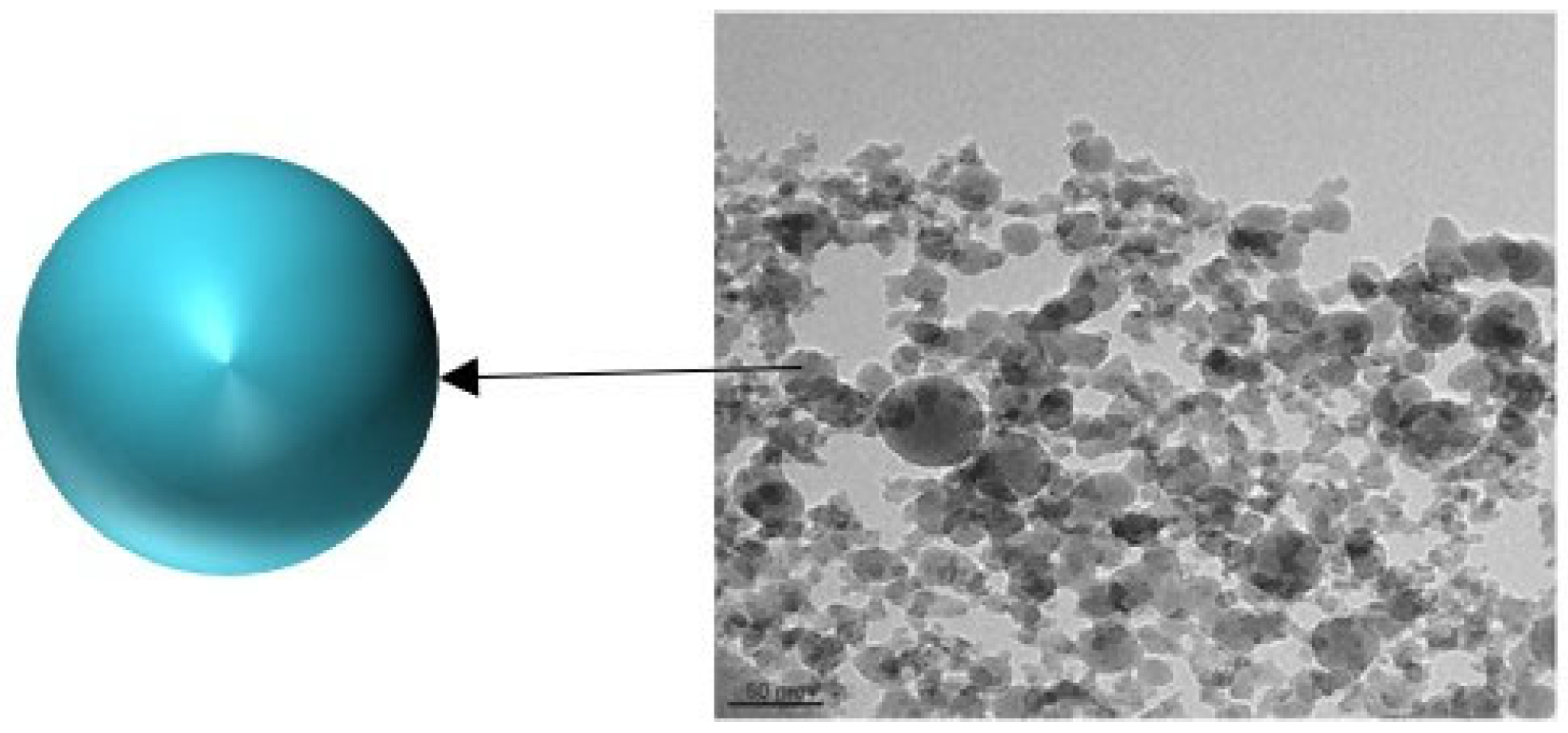

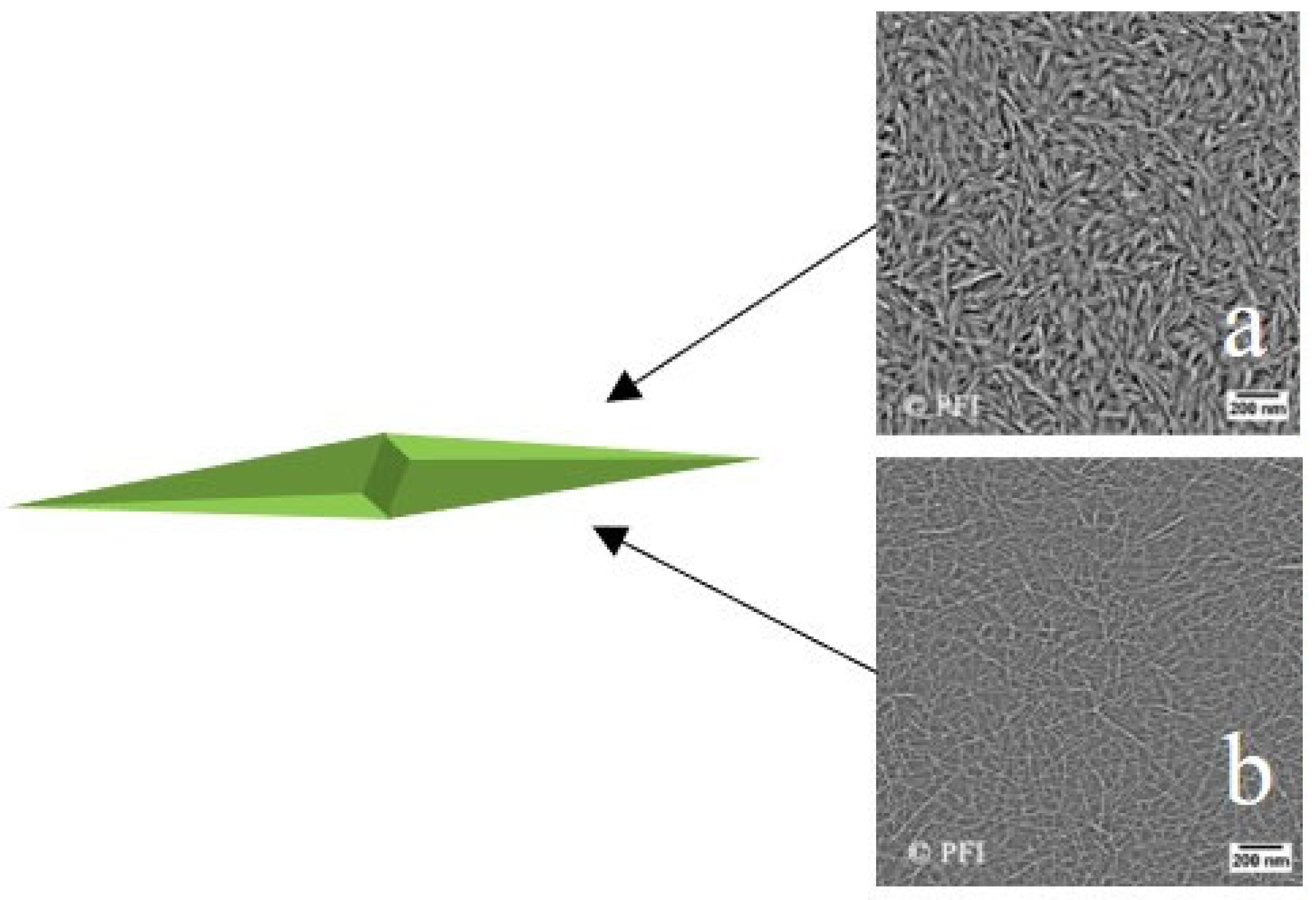

2. Inorganic Nanofluids

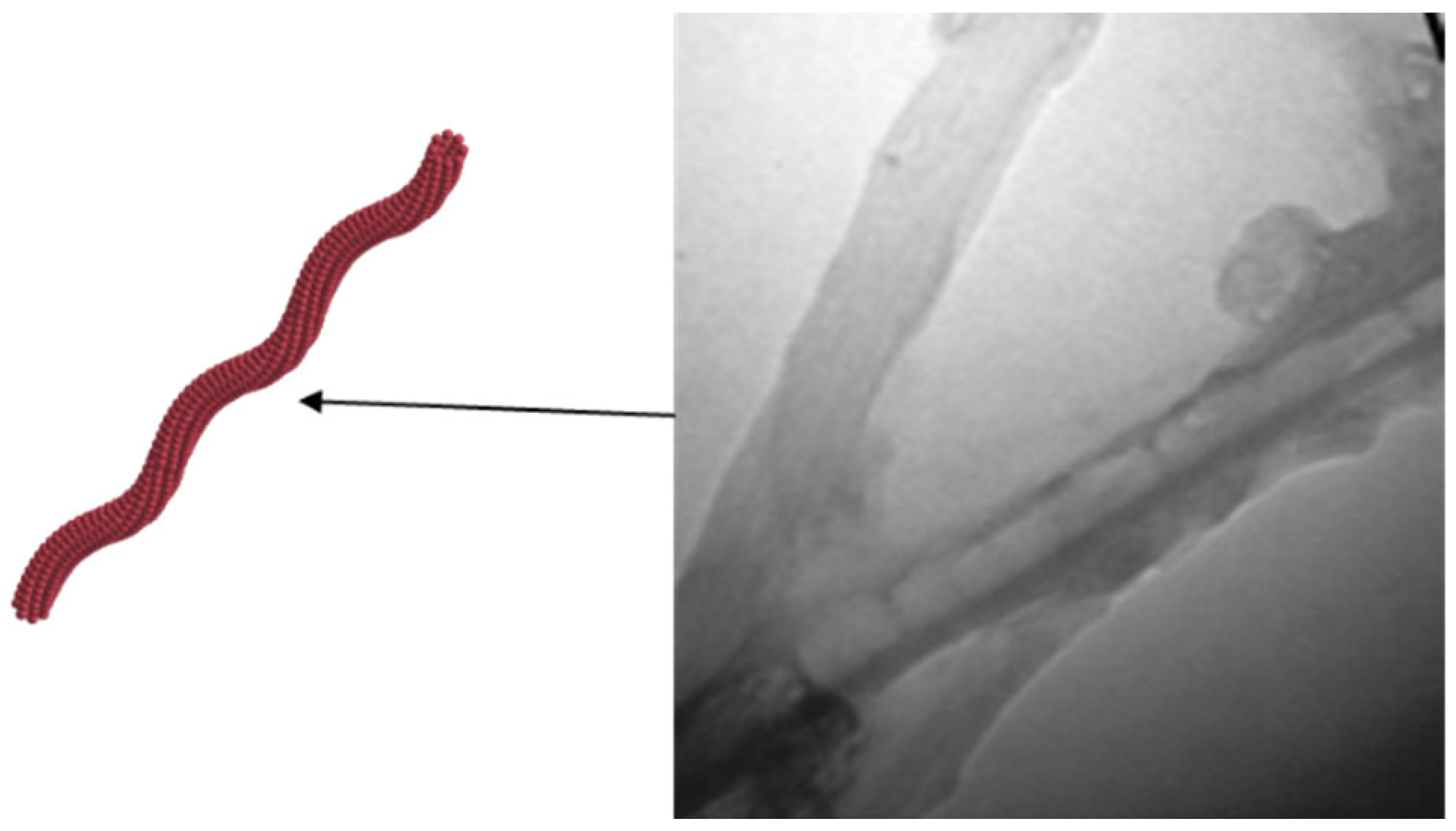

3. Organic Nanofluids

4. Organic–Inorganic Composite Nanofluid

|

Nanofluids |

Main Components |

Mechanism and Effect |

Ref |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Fe3O4 |

Fe3O4 NPs aqueous solution |

Increase oil recovery by 14% under the magnetic field. |

[15] |

|

TiO2 |

TiO2 NPs aqueous solution |

Reduce the forward and backward angles of water from 165.1° and 166.2° to 37.6° and 48.2°. |

[16] |

|

TiO2 NPs; xanthan gum solution |

Increase the CA of oil from 21° to 148°, increase oil recovery by 25%. |

[17] |

|

|

Al2O3 |

Spherical Al2O3 NPs aqueous solution |

Reduce crude oil viscosity, increase 3.1% oil recovery. |

[18] |

|

Sheet-like Al2O3 NPs aqueous solution |

Reduce the IFT, increase 10% oil recovery. |

[22] |

|

|

MgO |

MgO NPs aqueous solution |

Reduce the IFT to 3.7 under high temperature and pressure. |

[25] |

|

ZnO |

ZnO NPs; Steam |

Reduce crude oil viscosity; the efficiency of steam flooding has increased by 35.5%. |

[26] |

|

ZnO@PAM nanocomposites; cationic surfactants solution |

Reduced the IFT from 29.16 to 0.176 mN/m; decreased the CA of water from 145.86° to 12.79°; increase 30% oil recovery. |

[42] |

|

|

CuO |

CuO NPs; Surfactant solution |

Increase the thermal conductivity of rocks to 33%, thereby reducing the viscosity of crude oil. |

[27] |

|

SiO2 |

SiO2 NPs; KCl solution. |

Controlling fines migration and reducing the pressure drop in the porous media. |

[29] |

|

Janus C12 aqueous solution |

The Janus-C12 stabilized multiple O/W/O Pickering emulsions improve the oil recovery by 27.2%. |

[39] |

|

|

MoS2 |

MoS2 nanosheets; AOS solution |

The addition of modified nanosheets to the foam generation leads to 12.1% of increased oil recovery. |

[24] |

|

KH-550-MoS2 aqueous solution |

Reduce the IFT to 2.6 mN/m, reduce the CA of water from 131.2° to 51.7°; increase 14% oil recovery. |

[43] |

|

|

Polymer NPs |

Nanogel microsphere aqueous solution |

High water absorption and expansion performance under high temperature and high-salinity-conditions. |

[32] |

|

Cellulose nanocrystals |

CNCs; T-CNFs; LSW |

CNCs can reduce the IFT; T-CNFs can change the wettability of rocks; produced 5.8% of OOIP more oil than LSW. |

[33] |

|

Graphene Oxide |

Aqueous solution of GO-Su-HMDS |

Reduce the IFT from 18.45 to 8.8, change the wettability of rocks; increase oil recovery by 20%. |

[35] |

|

Halloysite nanotubes |

Aqueous solution of halloysite nanotubes containing surfactants inside |

Improved oil displacement by 16% compared to using surfactants alone. |

[40] |

|

Carbon nanotubes |

f-MWCNT-CTAB; LSSW |

Reduced the IFT to 0.3 mN/m, changing the dolomite slabs wettability from an oil-wet toward a neutral-wet state (128–105°), result in a 21% increase in oil recovery after secondary water injection. |

[42] |

References

- Choi, S.U.S.; Eastman, J.A. Enhancing thermal conductivity of fluids with nanoparticles. Asme Fed. 1995, 231, 99–105.

- Dolui, S.; Bhaumik, B.; De, S. Effect of a variable magnetic field on peristaltic slip flow of blood based hybrid nanofluid through a non-uniform annular channel. J. Mech. Med. Biol. 2023, 23, 2250070.

- Baïri, A. Effects of ZnO-H2O nanofluid saturated porous medium on the thermal behavior of electronics contained in tilted hemispherical cavity. An experimental and numerical study. Appl. Therm. Eng. 2018, 138, S924–S933.

- Sadabadi, H.; Sanati Nezhad, A. Nanofluids for performance improvement of heavy machinery journal bearings, A simulation study. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 2120.

- Sajid, M.U.; Bicer, Y. Performance Assessment of Spectrum Selective Nanofluid-Based Cooling for a Self-Sustaining Greenhouse. Energy Technol. 2021, 9, 2000875.

- Peng, B.; Zhang, L.; Luo, J.; Wang, P.; Ding, B.; Zeng, M.; Cheng, Z. A review of nanomaterials for nanofluid enhanced oil recovery. RSC Adv. 2017, 7, 32246–32254.

- Hamza, M.F.; Soleimani, H.; Ridha, S.; Ahmed, A.A.; Sikiru, S. Double layer chemical encapsulation of SiO2 nanoparticles for interfacial tension reduction under low salinity condition. J. Mol. Liq. 2023, 371, 121100.

- He, L.; Yang, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Z.; Shen, J. Removal of Ca2+ and Mg2+ from oilfield wastewater using reusable PEG/Fe3O4/GO-NH2 nanoadsorbents and its efficiency for oil recovery. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2020, 9, 104653.

- Yuan, S.; Wang, Q. New progress and prospect of oilfields development technologies in China. Pet. Explor. Dev. 2018, 45, 698–711.

- Luan, J.; Dong, P.; Zheng, J. Experimental studies on reaction laws during the process of air injection into the oil reservoirs with low permeability. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2020, 194, 107526.

- Nikolov, A.; Zhang, H. The dynamics of capillary-driven two-phase flow, The role of nanofluid structural forces. J. Colloid Interface 2015, 449, 92–101.

- Li, S.; Xu, X.; Li, W.; Wang, L.; Ning, H.; Zhong, S. Monodisperse SiO2 Microspheres with Large Specific Surface Area, Preparation and Particle Size Control. Res. Appl. Mater. Sci. 2021, 3, 17–23.

- Song, W.; Hatzignatiou, D.G. On the reduction of the residual oil saturation through the injection of polymer and nanoparticle solutions. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 208, 109430.

- Matteo, C.; Candido, P.; Vera, R.; Francesca, V. Current and future nanotech applications in the oil industry. Am. J. Appl. Sci. 2012, 9, 784.

- Esmaeilnezhad, E.; Van, S.L.; Chon, B.H.; Choi, H.J.; Schaffie, M.; Gholizadeh, M.; Ranjbar, M. An experimental study on enhanced oil recovery utilizing nanoparticle ferrofluid through the application of a magnetic field. J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 2018, 58, 319–327.

- Hosseini, M.S.; Khazaei, M.; Misaghi, M.; Koosheshi, M.H. Improving the stability of nanofluids via surface-modified titanium dioxide nanoparticles for wettability alteration of oil-wet carbonate reservoirs. Mater. Res. Express 2022, 9, 035005.

- Keykhosravi, A.; Vanani, M.B.; Aghayari, C. TiO2 nanoparticle-induced Xanthan Gum Polymer for EOR, Assessing the underlying mechanisms in oil-wet carbonates. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2021, 204, 108756.

- Samba, M.A.; Hassan, H.A.; Munayr, M.S.; Yusef, M.; Eschweido, A.; Burkan, H.; Elsharafi, M.O. Nanoparticles EOR aluminum oxide (Al2O3) used as a spontaneous imbibition test for sandstone core. ASME International Mechanical Engineering Congress and Exposition. Am. Soc. Mech. Eng. 2019, 59438, V006T06A054.

- Mansouri, M.; Nakhaee, A.; Pourafshary, P. Effect of SiO2 nanoparticles on fines stabilization during low salinity water flooding in sandstones. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2019, 174, 637–648.

- Mollick, M.M.R.; Bhowmick, B.; Mondal, D.; Maity, D.; Rana, D.; Dash, S.K.; Chattopadhyay, S.; Roy, S.; Sarkar, J.; Acharya, K.; et al. Anticancer (in vitro) and antimicrobial effect of gold nanoparticles synthesized using Abelmoschus esculentus (L.) pulp extract via a green route. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 37838–37848.

- Liu, Y.; Liang, F.; Wang, Q.; Qu, X.; Yang, Z. Flexible responsive Janus nanosheets. Chem. Commun. 2015, 51, 3562–3565.

- Zaid, H.M.; Radzi, N.S.A.; Latiff, N.R.A.; Shafie, A. Effect of morphology of aluminium oxide nanoparticles on viscosity and interfacial tension (IFT) and the recovery efficiency in enhanced oil recovery (EOR). AIP Conf. Proc. 2014, 1621, 705–710.

- Pranav, T.; Navpreet, K.; Vinay, S.; Mobin, S.M. High-yield graphene produced from the synergistic effect of inflated temperature and gelatin offers high stability and cellular compatibility. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2018, 20, 20096–20107.

- Raj, I.; Liang, T.; Qu, M.; Xiao, L.; Xian, C. An experimental investigation of MoS2 nanosheets stabilized foams for enhanced oil recovery application. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2020, 606, 125420.

- Nowrouzi, I.; Manshad, A.K.; Mohammadi, A.H. Effects of TiO2, MgO, and γ-Al2O3 nano-particles in carbonated water on water-oil interfacial tension (IFT) reduction in chemical enhanced oil recovery (CEOR) process. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 292, 111348.

- Tajmiri, M.; Ehsani, M.R. Water Saving by using Nanoparticles in Heavy Oil Reservoir through Thermal EOR Method, Special Pertaining to ZnO & CuO. Ambient Sci. 2017, 4, 7–12.

- Barahoei, M.; Hezave, Z.; Sabbaghi, S.; Ayatollahi, S. Copper oxide nano-fluid stabilized by ionic liquid for enhancing thermal conductivity of reservoir formation, Applicable for thermal Enhanced Oil Recovery processes. Chem. Ind. Chem. Eng. Q. 2016, 22, 211–225.

- Mortimer, M.; Kasemets, K.; Heinlaan, M.; Kurvet, I.; Kahru, A. High throughput kinetic Vibrio fischeri bioluminescence inhibition assay for study of toxic effects of nanoparticles. Toxicol. Vitr. 2008, 22, 1412–1417.

- Tangestani, E.; Vafaie, S.M.; Shadman, M.M.; Kazemi, T.E.; Ahmadi, S. Performance of low-salinity water flooding for enhanced oil recovery improved by SiO2 nanoparticles. Pet. Sci. 2019, 16, 357–365.

- Sun, Z.; Wang, X.; Kang, X. The Reservoir Adaptability Evaluation and Oil Displacement Mechanism of a Novel Particle-Type Polymer Flooding Technology. Soc. Sci. Electron. Publ. 2021, 3898483.

- Caplan, S.P.C.; Silva, T.B.G.; Franscisco, A.D.S.; Lachter, E.R.; Nascimento, R.S.V. Sulfonated Polystyrene Nanoparticles as Oleic Acid Diethanolamide Surfactant Nanocarriers for Enhanced Oil Recovery Processes. Polymers 2019, 11, 1513.

- Esfahlan, M.S.; Khodapanah, E.; Tabatabaei-Nezhad, S.A. Fabrication, optimization and characterization of preformed-particle-gel containing nanogel particles for conformance control in oil reservoirs. Polym. Bull. 2022, 79, 7137–7159.

- Aadland, R.C.; Akarri, S.; Heggset, E.B.; Syverud, K.; Torster, O. A core flood and microfluidics investigation of nanocellulose as a chemical additive to water flooding for EOR. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1296.

- Huang, P.; Jia, H.; Wang, T.; Xu, Y.; Liu, D. Effects of modification degrees on the colloidal stability of amphiphilic Janus graphene oxide in aqueous solution with and without electrolytes. Langmuir 2021, 37, 10061–10070.

- Jafarbeigi, E.; Salimi, F.; Kamari, E.; Mansouri, M. Effects of modified graphene oxide (GO) nanofluid on wettability and IFT changes, Experimental study for EOR applications. Pet. Sci. 2022, 19, 1779–1792.

- Wang, B.; Hu, J.; Liu, K.; Zhang, L.; Jiang, H.; Li, C. Reinforcement mechanism of silica surface hydroxyl, The opposite effect. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 623, 157000.

- Zhou, R.; Ma, H.; Zhou, Z.; Xu, W.; Ren, F.; Li, C. Preparation of SiO2 particles with silicone-methoxy groups on surface and its co-curing hydroxyl silicone oil. Mater. Res. Express 2020, 7, 065309.

- Afifi, H.R.; Mohammadi, S.; Derazi, A.M.; Alemi, F.M. Enhancement of smart water-based foam characteristics by SiO2 nanoparticles for EOR applications. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 627, 127143.

- Jia, H.; Dai, J.; Miao, L.; Wei, X.; Tang, H.; Huang, P.; Liu, D. Potential application of novel amphiphilic Janus-SiO2 nanoparticles stabilized O/W/O emulsion for enhanced oil recovery. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2021, 622, 126658.

- Ojo, O.F.; Farinmade, A.; John, V.; Nguyen, D. A nanocomposite of halloysite/surfactant/wax to inhibit surfactant adsorption onto reservoir rock surfaces for improved oil recovery. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 8074–8084.

- Asl, F.O.; Zargar, G.; Manshad, A.K.; Iglauer, S.; Keshavarz, A. Experimental investigation and simulation for hybrid of nanocomposite and surfactant as EOR process in carbonate oil reservoirs. Fuel 2022, 319, 123591.

- Mahdavinezhad, M.; Kazemi-Beydokhti, A.; Sanati, A.; Malayeri, M.R. Efficacy of f-MWCNT-CTAB nano-complex in low-salinity seawater EOR operation. J. Pet. Sci. Eng. 2022, 208, 109532.

- Liang, T.; Hou, J.; Xi, J. Mechanisms of nanofluid based modification MoS2 nanosheet for enhanced oil recovery in terms of interfacial tension, wettability alteration and emulsion stability. J. Dispers. Sci. Technol. 2023, 44, 26–37.