Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Pavel Peretyagin | -- | 6660 | 2023-12-05 11:38:50 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 6660 | 2023-12-06 03:33:39 | | | | |

| 3 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 6660 | 2023-12-06 03:38:28 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Sotova, C.; Yanushevich, O.; Kriheli, N.; Grigoriev, S.; Evdokimov, V.; Kramar, O.; Nozdrina, M.; Peretyagin, N.; Undritsova, N.; Popelyshkin, E.; et al. Dental Implants Materials. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52371 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Sotova C, Yanushevich O, Kriheli N, Grigoriev S, Evdokimov V, Kramar O, et al. Dental Implants Materials. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52371. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Sotova, Catherine, Oleg Yanushevich, Natella Kriheli, Sergey Grigoriev, Vladimir Evdokimov, Olga Kramar, Margarita Nozdrina, Nikita Peretyagin, Nika Undritsova, Egor Popelyshkin, et al. "Dental Implants Materials" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52371 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Sotova, C., Yanushevich, O., Kriheli, N., Grigoriev, S., Evdokimov, V., Kramar, O., Nozdrina, M., Peretyagin, N., Undritsova, N., Popelyshkin, E., & Peretyagin, P. (2023, December 05). Dental Implants Materials. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52371

Sotova, Catherine, et al. "Dental Implants Materials." Encyclopedia. Web. 05 December, 2023.

Copy Citation

The development of dental implantology is based on the detailed study of the interaction of implants with the surrounding tissues and methods of osteogenesis stimulation around implants, which has been confirmed by the increasing number of scientific publications presenting the results of studies related to both the influence of the chemical composition of dental implant material as well as the method of its surface modification on the key operational characteristics of implants.

dental implant

Ti and its alloys

stainless steels

Zr and its alloys

1. Introduction

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), oral diseases are prevalent noncommunicable diseases that afflict almost half of the world’s population, i.e., around 45% or 3.5 billion individuals of all ages [1][2]. Complete tooth loss, or adentia, is steadily increasing with a peak occurrence in older age groups. Currently, there are over 350 million cases worldwide, resulting in a global prevalence rate of almost 6.82% [1]. In Russia, partial tooth loss is estimated to affect between 40% and 75% of the population, corresponding to a range of 58 million to 108 million people. And, the number of patients with such problems will increase as the average age of the population rises [3]. In addition to tooth loss caused by accidents (trauma), dental decay and gum diseases are key factors contributing to teeth loss. Untreated caries in permanent teeth affect 2.3 billion individuals, while over 514 million children suffer from untreated deciduous teeth caries, and more than 1 billion people, which represent 19% of the world’s population over 15 years of age, have periodontal disease [1].

Thus, the development of the dental implants market is driven by the high prevalence of oral diseases and the goal of improving people’s quality of life. The worldwide market for dental implants was estimated at $9.27 billion in 2022 and $10.09 billion in 2023, with a forecasted compound annual growth rate (CAGR) of 8.95% to hit $18.42 billion by 2030 [4]. The dental implants market is growing due to a rise in tooth loss cases, increasing demand for cosmetic dentistry, and advancements in dental implant technology [5].

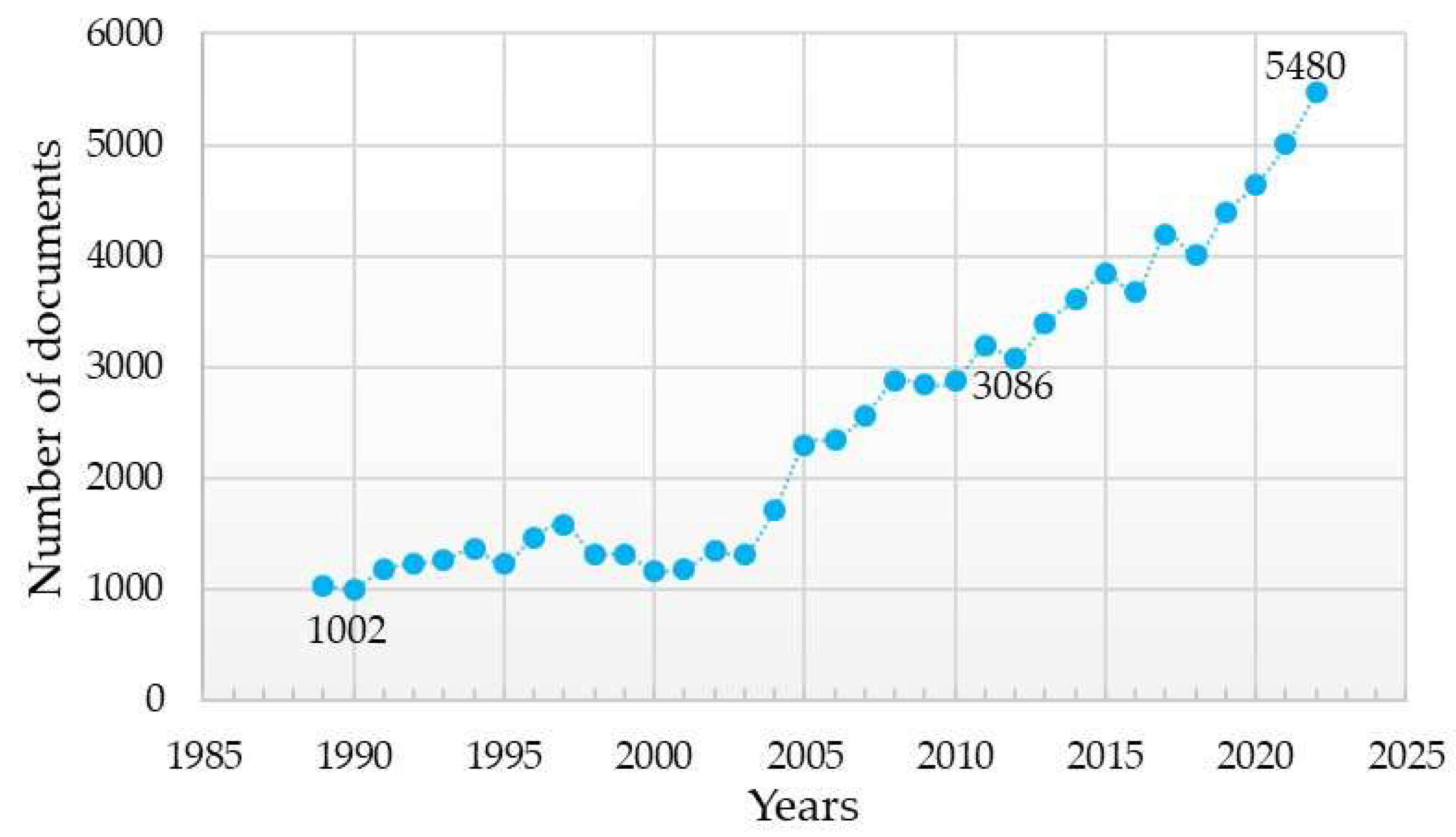

The advancement of dental implantology is based on a detailed study of the interaction of implants with surrounding tissues and methods of stimulating osteogenesis around implants. This has been demonstrated by the increasing number of scientific articles presenting the results of studies on the influence of the chemical composition of the dental implant material and the method of its surface modification on the key characteristics of dental implants (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Analysis of search results for publications using the keywords “dental implant” from 1989, the year when the first patent for a titanium implant was registered, up to the present (according Scopus, ScienceDirect).

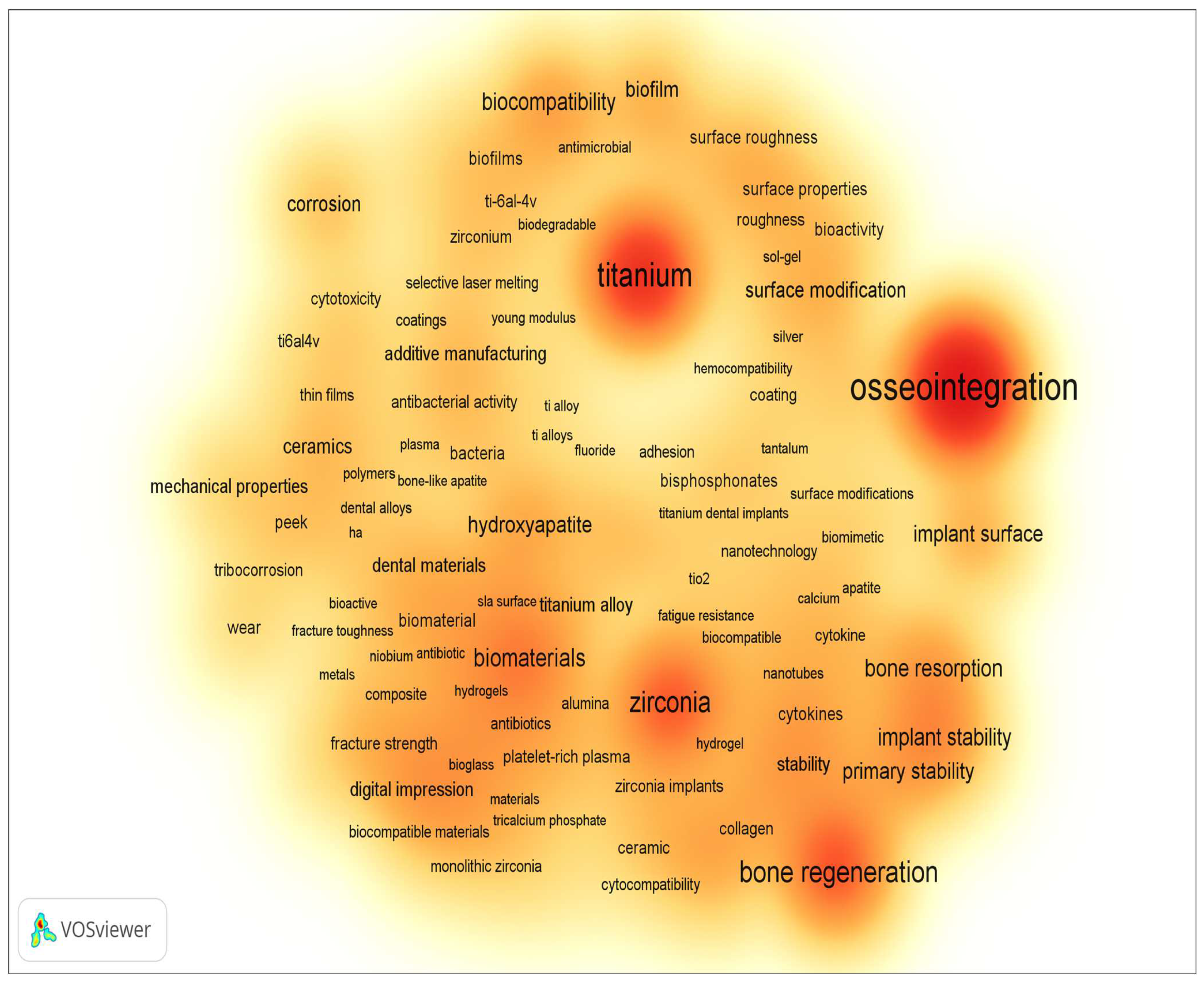

Figure 2 and Figure 3 display the word cloud generated by keywords from the previously mentioned sample, limited to the period from 2014 to the present, where keywords related only to implant material and surface modification methods and properties were selected. According to the results presented, the main requirements for implants are to provide and/or enhance the following properties (these have been the focus of scientific research on the improvement of dental implants):

Figure 2. Overlay visualization of word cloud based on the keywords (dental implant) of publications from 2014 to present (according Scopus, ScienceDirect).

Based on their biocompatibility, materials for dental implants can be divided into biotolerant, bioinert, and bioactive [26]. Biotolerant materials, such as stainless steel and cobalt–chromium alloys, induce osteogenesis in the bone to respond to the irritating effect of the implant in the tissue contact zone. In this case, a layer of soft fibrous tissue separates the bone from the implant composed of these materials. The application of bioinert materials, including alumina, zirconia, titanium, its alloys, and tantalum, leads to the development of contact osteogenesis given favorable mechanical conditions. This means that these materials directly bond with the bone tissue. Bone integration occurs because the surface of such materials is chemically inert to the surrounding tissues and fluids. Bioactive materials such as calcium phosphate ceramics, glass, and glass ceramics cause connective osteogenesis—the direct chemical bonding of the implant with the surrounding bone—due to the presence of free calcium and phosphate on the surface and of their interaction.

In addition, a number of scientific studies have been devoted to the influence of the above-mentioned factors on other properties of implants, for example:

Figure 3. Density visualization of word cloud based on the keywords (dental implant) of publications from 2014 to present (according Scopus, ScienceDirect).

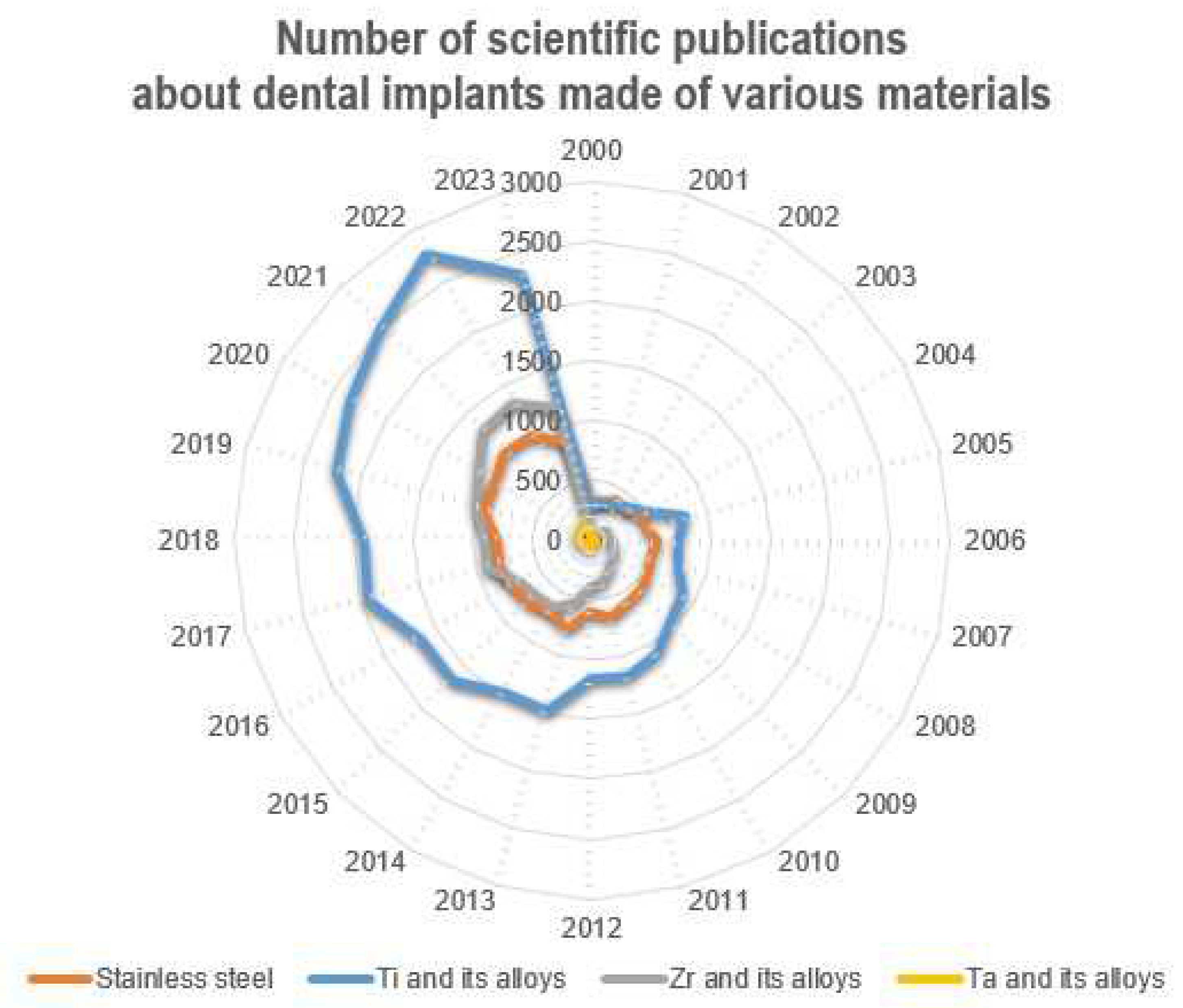

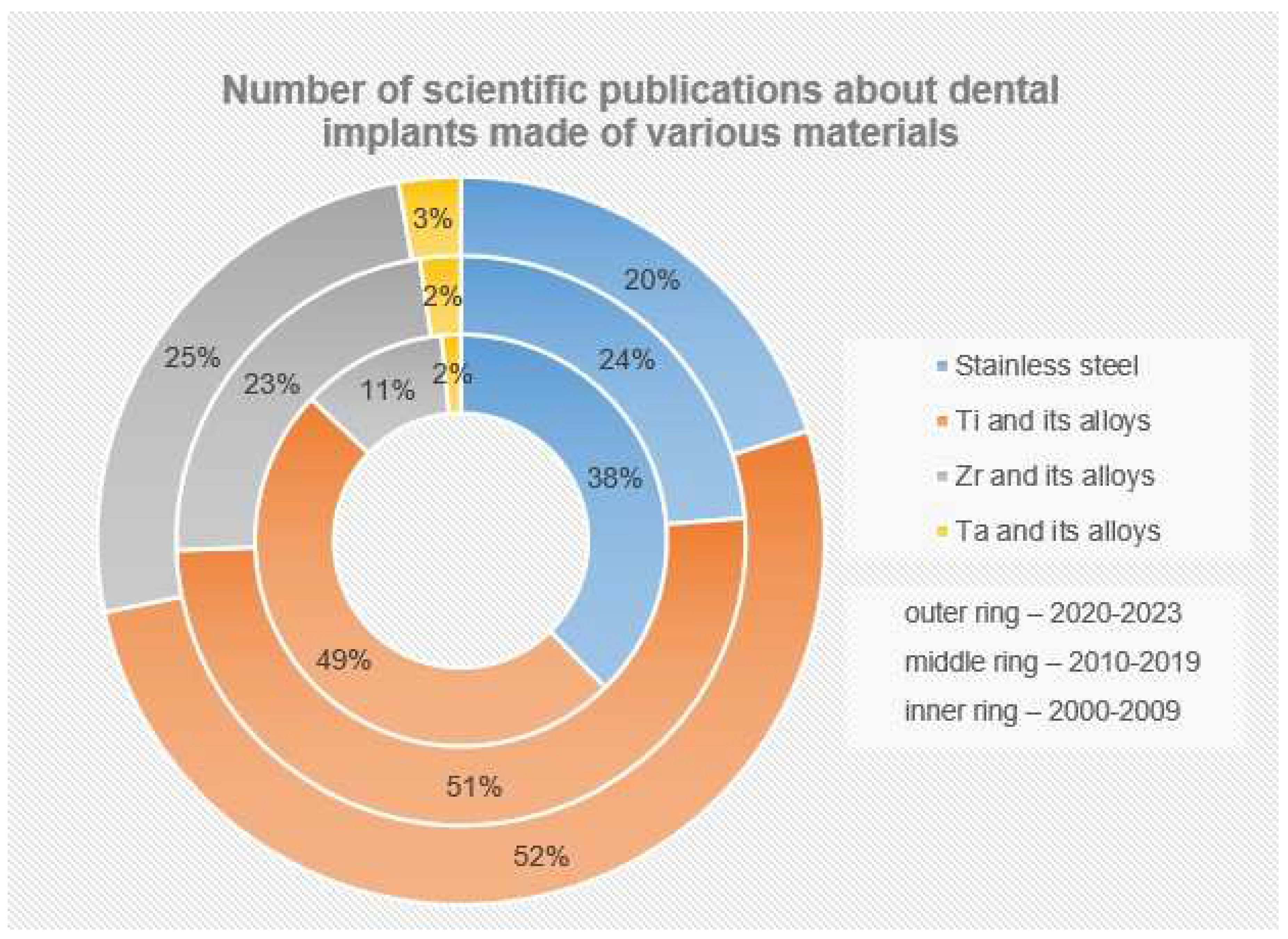

Currently, according to numerous fundamental and applied studies, the main materials for dental implants are titanium and its alloys, stainless steels, zirconium alloys (including ceramics based on zirconium dioxide), and tantalum and its alloys, as well as other materials (ceramics based on aluminum oxide, silicon nitride, etc.). It should be noted that due to the lowest osseointegration and the presence of harmful impurities, the number of publications where the objects of research are implants made of stainless steels is significantly reduced (Figure 4). The great variety of dental implants based on chemical composition and surface layer modification technology indicates that the problem of choosing the optimal material for implant manufacturing has not been finally solved to date.

Figure 4. Number of scientific publications in the search results of publications for the keywords (dental implant*) from 2000 to the present (according to ScienceDirect).

2. Dental Implant Materials

An artificial tooth (denture) is a complex construction (Figure 5) consisting of an implant (1), abutment (2) and crown (3). The implant itself is completely immersed deep into the bone, and the crown is located above the gingiva; the abutments connect them with each other, except in the use of one-piece implants, in which the intraosseous part and the abutment are immediately connected into a monolithic element (one-piece type of implants). However, this variant is mainly used for full jaw restorations, i.e., basal implantation (in one-stage implantation protocols involving immediate loading with a prosthesis).

Figure 5. Dental prosthesis: 1—implant, 2—abutment, 3—crown.

The implant material must meet several requirements [51]:

-

To be strong enough to withstand chewing pressure (sometimes exceeding 100 kgf/cm2) and not to destroy the bone with its weight;

-

To be well machinable at the manufacturing stage in order to retain its shape throughout its entire service life;

-

To not be destroyed (not corroded) by the action of the biological environment (saliva, blood, etc.);

-

To not show toxic, allergenic, and carcinogenic effects on the body;

-

To not provoke an increase in galvanic currents when interacting with metal structures installed in the patient’s mouth.

The main materials for the production of dental implants, as mentioned before, are mainly metal alloys based on titanium, iron, and tantalum, as well as ceramics based on zirconium (Figure 6). At the same time, starting in the last twenty years, the number of studies in which the implants made of stainless steels are the objects of studies has considerably decreased (from 38% to 20%), and this has been connected with the presence of harmful impurities in the steel composition and the insufficient corrosion resistance and biocompatibility of these implants. At the same time, titanium and its alloys, during this period, have steadily occupied the leading positions (~50%), and today, they are the main materials for the production of commercialized dental implants.

Figure 6. Number of scientific publications in the search results of publications for the keywords (dental implant*) from 2000 to the present (according to ScienceDirect). The number of publications (%) is presented relative to their total number for all groups of materials (SS+Ti+Zr+Ta).

2.1. Titanium and Its Alloys

The main materials for the production of dental implants are titanium and its alloys. For commercialized dental implants, the following grades of alloys are mainly used [52][53][54][55][56][57][58][59][60][61][62][63][64][65][66][67]:

The chemical and mechanical properties of these alloys meet the requirements for materials used in dental implantation. They are characterized by high strength at low density, high elasticity (five times higher than the elasticity of bone [26]), and bioinertness [72], but not all titanium alloys are used in dentistry. However, with all these positive properties of titanium and its alloys, they are characterized by low resistance to shear and wear, especially under friction conditions [26].

At the same time, dental implants should be designed with a high coefficient of friction and a low modulus of elasticity to avoid excessive stress on the bone [73]. The modulus of elasticity of solid titanium alloys is 100–115 GPa, while the values for different types of bone are 0.5–20 GPa. This mechanical mismatch is the reason why healthy bones are underloaded and the “stress shielding” effect occurs [74]. The “stress shielding” effect leads to the healthy bone resorption and loosening of the implant, as a result of which the implant functioning period decreases.

This is why studies on obtaining “new”-generation titanium alloys with mechanical properties approaching the properties of bone tissue are conducted widely enough. All of them are aimed at the volumetric alloying of titanium alloys with β-stabilizers (Nb, Ta, Zr, and Mo) to obtain a single-phase β-alloy structure since β-Ti alloy has a lower modulus of elasticity and higher strength than α-Ti alloys and (α+β)-Ti alloys [75]. In addition, the β-type titanium alloy has good technological properties (in particular, cold-pressure machinability), which reduces the cost of implant production [76].

Ti-6Al-4V alloy is 3.0–3.5 times stronger than commercially pure titanium and cheaper to produce [77], which makes it indispensable in the manufacture of thin, reliable implants with special compression threads that are placed in the dense basal regions of the jawbone [52]. However, vanadium and aluminum contained in the alloys have been shown [78][79] to have toxic effects on biological entities and can lead to long-term health problems, such as neurological diseases and Alzheimer’s disease [80][81][82][83], while aluminum and iron (although it is not a toxic element) lead to the formation of a connective tissue layer around the implant and to significant tissue contamination, which is a sign of the insufficient bioinertness of the metal. In addition, iron suppresses the growth of organic cultures. Also, the degree of tissue adhesion to the implants made of titanium alloys is somewhat worse than that to unalloyed titanium [84].

The introduction of Nb into the alloy composition, instead of toxic vanadium, improves the bioinertness of alloys and leads to a significant increase in the wear resistance of alloys of the Ti-Al-Nb system in comparison with Ti-Al-V alloys, with comparable values in terms of fatigue strength and the service lives of products. Thus, it was shown in [85] that the wear resistance of Ti-21Al-29Nb and Ti-15Al-33Nb alloys was more than three times higher than that of Ti-6Al-4V. At the same time, at low- and multi-cycle fatigue tests on samples from both alloys, the following were observed: the nucleation of surface cracks, furrows in the zone of propagation of a stable fatigue crack, and equiaxed dimples in the zone of propagation of a fast-fatigue crack. The Ti-15Al-33Nb alloy exhibited ductile fracture morphology whereas the Ti-21Al-29Nb alloy tended to exhibit a more brittle fracture morphology.

The introduction of yttrium-stabilized zirconium oxide into the alloy of the Ti-Al-Nb system increases the Vickers microhardness and biocorrosion resistance of the alloy and improves the corrosion resistance of the alloy [86].

Moreover, Nb is non-toxic and has no harmful effect on the human body, which can be a result of its ability to form a protective oxide film on the implant surface like titanium. According to a study [87], Nb demonstrated good compatibility in contact with cells, providing mitochondrial activity and cell growth. Moreover, Ti-Nb alloys release fewer metal ions into the surrounding tissues compared to Ti-Al-V, Ti-Ni, and Ti-Mo alloys [88][89]. Ti-Nb alloys also have good mechanical strength (e.g., for Ti-42Nb alloy, the tensile strength is 683.17 ± 16.67 MPa and the compressive strength is 1330.74 ± 53.45 MPa [90]) and hardness (microhardness increases with increasing Nb content in the alloy—276 HV0.5 for Ti-13Nb and 287 HV0.5 for Ti-28Nb [91]) because Nb dissolves in the Ti crystal lattice, forming a solid substitution solution, which leads to the hardening of the solid solution β [92].

While, in binary Ti-Zr alloys, zirconium has almost no effect on β-phase stabilization, in multicomponent Ti alloys containing Nb or Ta, Zr acts as an effective β-stabilizer [76]. At the same time, Ti-Nb-Zr (TNZ) alloys have high strength (the tensile strengths of the alloys are in the range of 704–839 MPa) while remaining at the level of Ti-Nb alloys in terms of their low modulus of elasticity (in the range of 62–65 GPa) [76]. In addition, the new series of β-TNZ alloys have excellent cytocompatibility [76][93]. According to [93], due to its good mechanical properties (E = 84.1 GPa), high corrosion resistance, and lack of cytotoxicity toward MC3T3 and NHDF cells, this Ti-13Nb-13Zr alloy can be successfully used in implants, including in bone tissue engineering and dental products.

The additional alloying of a TNZ alloy with tantalum (TNZT alloy) leads to an increase in the corrosion resistance of the alloy in the environment of biological fluids (e.g., saliva, biofilm, and fluoride) while maintaining (with a decreasing trend) a relatively low modulus of elasticity (E = 82 GPa) [94]. The excellent biological and corrosion performance results are achieved mainly due to the oxide film (TiO2, Nb2O5, ZrO2, or Ta2O5) spontaneously formed on Ti and its alloys when exposed to atmospheric air [94]. The introduction of silicon into the composition of the TNZT alloy makes it possible to further reduce the elastic modulus (up to 50 GPa) [95]. At the same time, the Ti-Nb-Zr-Ta-Si alloy has a significant compatibility with bone tissue in comparison with the cp-Ti alloy, which is widely used in dental implants. Thus, in in vitro tests, in comparison with cp-Ti, Ti-Nb-Zr-Ta-Si alloy showed better adhesion, proliferation, and alkaline phosphatase (ALP) activity and promoted the expression of osteocalcin (OCN) mRNA in MG63 cells [95].

The addition of Mo not only stabilizes the β-phase of alloys but also increases the strength and maintains the ductility of Ti-Nb alloys, while Ti-Nb-Mo alloys are not prone to riveting [75]. This leads to a decrease in the modulus of elasticity, which is lower the more Mo is present in the alloy composition. Thus, the reduced elastic modulus (Er measured via nanoindentation) decreases from 67.0 GPa for the Ti-26Nb-2Mo alloy to 54.5 GPa for the Ti-26Nb-8Mo alloy (with the lowest elastic modulus) [75]. In addition, the Ti-26Nb-8Mo alloy has good wear resistance and higher impact toughness than the cp-Ti alloy.

Despite the biocompatible composition, improved corrosion resistance, and low modulus of elasticity of complex-alloyed titanium alloys, serious aspects limiting the effectiveness of titanium alloys for biomedical applications are low tribocorrosion resistance in biological body environments and an inability to prevent bacterial infection in the early stages of recovery [96][97]. The latter can be addressed by alloying with antibacterial components such as Cu, Zn, Ag, and Ga [98].

In one study, although the addition of alloying elements Ga and/or Cu to the Ti-Nb matrix resulted in a slight increase in the elastic modulus to 73–78 GPa (for the base alloy Ti-45Nb, E = 64 GPa), the elastic modulus was still lower than that of the alloys used in clinical practice [99]. Among β-Ti-Nb-Ga alloys, increased wear resistance was noted for the Ti-45Nb-8Ga alloy [100], which is associated with increased microhardness (it increased by 32–44% with the addition of Ga and/or Cu, which the authors [99] attributed to the hardening of solid solutions). Also, the addition of Ga to Ti-45Nb leads to both improved corrosion resistance under mechanical loading as well as the increased strength of the alloy [100].

Another group of alloys used for the fabrication of dental implants, which have been clinically approved and already successfully commercialized, comprises Ti-Zr alloys [68][69][70]. For example, Ti-Zr alloys can compete in the fabrication of small-diameter dental implants. In these cases, cp-Ti is more prone to fracture (due to its relatively low compressive strength), and the use of Ti-Al-V alloy is undesirable due to the toxicity associated with the release of Al and V.

For binary Ti-Zr alloys (as mentioned earlier), Zr is a neutral component with respect to titanium and easily dissolves in both α- and β-solid substitution solutions of unlimited solubility of Ti(Zr) [101] (while strengthening it due to distortion of the crystal lattice of titanium when its atoms are replaced by zirconium atoms [102][103]) since it undergoes a similar allotropic transformation at a close phase transition temperature [104].

Ti-Zr alloys have a predominantly α-crystalline structure, which predetermines the enhanced mechanical properties and excellent electrochemical properties of these alloys [98][103]. Thus, the addition of 5 and 10 wt.% Zr to Ti allowed more than doubling the microhardness of the alloy (HV 416–434) compared to the microhardness of pure titanium cp-Ti (HV ~188), surpassing even the hardness of the Ti-6Al-4V alloy (HV 354) [105]. The tensile strength of binary Ti-Zr alloys also increases with increasing zirconium concentration in the alloy. In [106], it was shown that the tensile strength of Ti-15Zr alloy exceeds that of cp-Ti by about 10–15% (950 MPa vs. 860 MPa, approximately), which the authors attributed, first, to the hardening of the solid solution due to alloying, second, to the refinement of its grain size (1–2 μm in Ti-15Zr as opposed to 20–30 μm in cp-Ti), and third, to the riveting obtained during sample fabrication (strain hardening). However, Ti-Zr alloys have an increased modulus of elasticity, and the modulus of elasticity increases with increasing zirconium concentration in the alloy (for Ti-5Zr, Ti-10Zr, and Ti-15Zr alloys the values were ~86, ~95, and ~110 GPa, respectively [102]), but for Ti-Zr alloy with a Zr concentration of up to 10 wt.%, the modulus of elasticity was significantly lower than for the widely used Ti-6Al-4V alloy, which had a higher elastic modulus (~115 GPa [100]). At the same time, the minimum modulus of elasticity has an alloy containing about 7.5 wt.% Zr [102].

Also, Ti-Zr alloys demonstrate increased corrosion resistance in comparison with traditional titanium alloys, which can be associated with the formation of passivating ZrO2 film on the implant surface. Thus, Zr for Ti is an anodic alloying component, which directly reduces its anodic activity [107], i.e., ZrO2 is a more stable oxide than TiO2. And, although Ti4+ ions are more mobile than Zr4+ ions, which leads to a significant reduction in the amount of ZrO2 oxide in the outer surface layer, the amount of the latter is proportional to the concentration of Zr in the alloy [105]. Higher corrosion protection for Ti-Zr alloys may also be facilitated by their increased hardness (and therefore wear resistance), which may prevent damage to the passivation film by mechanical stresses and ensure long-term rehabilitation success by reducing both the likelihood of corrosion in physiologic environments and the likelihood of impaired osseointegration [108]. In addition, it was shown in a study [105] that higher Zr concentrations resulted in enhanced albumin adsorption (albumin adsorption values for cp-Ti, Ti-6Al-4V, Ti-5Zr, and Ti-10Zr were 600, 650, 650, 750 mg/mL, respectively), suggesting, according to the authors, that there was no negative effect on initial cell adhesion.

Due to the sensitivity of mechanical properties to the structure of binary Ti-Zr alloys, it is possible to reduce the modulus of elasticity by applying strengthening heat treatment (accelerated cooling after heating above the β→α transformation temperature) or strain hardening, which will change the distance between atoms, and this, in turn, can lead to a change in the bonding force between atoms and, as a result, the modulus of elasticity [102][109]. In addition, the use of additive technologies to create porous structures can also contribute to a decrease in the elastic modulus while maintaining the relatively high strength of the alloys. For this connection, additional studies are needed to reveal the influence of technologies for producing products from binary Ti-Zr alloys on their mechanical properties.

The additional alloying of Ti-Zr alloys with β-stabilizers (Nb, Mo and/or Ta) leads to a decrease in the elastic modulus [105][110][111] since the introduction of these components promotes the formation of β-phase in the structure, characterized by the lowest elastic modulus among all phases of titanium alloys [112]. Nb reduces the hardness of Ti-Zr alloy to a value close to the value of cp-Ti (~ 200 HV) [105], which is also associated with the appearance of a softer β-phase in the structure. The influence of zirconium concentration on the hardness of ternary Ti-Nb-Zr alloys is similar to that of binary Ti-Zr alloys; a study [105] showed the higher hardness of Ti-Nb-Zr alloys with higher Zr concentrations (in the range of zirconium concentrations of up to 10 wt.%).

However, as shown by studies, in complex alloys such as Ti-Zr-Nb-Mo, increasing the concentration of Zr from 34 to 40% (by replacing it with niobium while keeping the content of titanium and molybdenum constant) leads to a decrease in hardness (243 ± 4, 2 HV, 238 ± 2.74 HV, and 237 ± 3.07 HV for Ti-34Zr-17Nb-1Mo, Ti-37Zr-14Nb-1Mo, and Ti-40Zr-11Nb-1Mo alloys, respectively) and alloy elastic modulus (75, 72, and 69.5 GPa for Ti-34Zr-17Nb-1Mo, Ti-37Zr-14Nb-1Mo, and Ti-40Zr-11Nb-1Mo alloys, respectively) [111] (in contrast to alloys with low zirconium content, i.e., up to 15 wt.%, for which hardness and elastic modulus increase with an increasing Zr concentration in the alloy [102]).

Biosafety evaluation tests (in accordance with the ISO 10993 series, [113]) of Ti-Zr alloyed with Nb and Ta [110] did not reveal any adverse (negative) effects either during extraction simulating normal use or under conditions of exaggerated extraction, which the authors attributed to the small number of released Ti ions. Thus, the concentrations of Ti in 0.9% NaCl + HCl solution when the samples from Ti-15Zr-4Nb, Ti-15Zr-4Nb-1Ta, and Ti-15Zr-4Nb-4Ta alloys were immersed in it were 0.4, 0.27, and 0.32 μg/mL, respectively. The authors of the study [110] substantiated such results via the presence of a passivating TiO2 film formed on the Ti alloy surface and containing Nb2O5-, ZrO2-, and Ta2O5- oxide films, which inhibited the yield of metal ions.

Another study [114] showed the prospects of the biomedical application of Ti-Zr alloys additionally alloyed with Fe. The Ti-6Zr-xFe alloy has an (α+β)-structure. With an increasing Fe content, from 4 to 7 wt.%, the volume fraction of α-phase decreases, the fraction of β-phase increases, and the grain size of the alloy as a whole decreases. This leads to an increase in microhardness (264–348 NV), the tensile strength (748–994 MPa) of cast Ti-6Zr-xFe alloys due to the hardening of the solid solution (due to iron alloying) and formation of ω-phase, and elastic modulus (90–94 GPa). At the same time, the alloys Ti-6Zr-4Fe and Ti-6Zr-5Fe (with the lowest Fe content) showed better corrosion resistance.

In each of the binary titanium alloys Ti-Ta and Ti-Mo, alloying with tantalum or molybdenum leads to higher strength and lower modulus of elasticity in the alloy compared to cp-Ti (similar to the effect of niobium) since Ta and Mo are also β-stabilizers. Thus, in a study, Ti-40Ta and Ti-50Ta alloys had higher tensile strength values compared to Ti-6Al-4V (786, 724, and 689 MPa, respectively), which were 14% and 8.9% higher than that of Ti-6Al-4V material [115], and the Ti-40Ta alloy with a biomimetic lamellar structure (obtained using sequential spark plasma sintering at 1200 °C followed by hot rolling at a strain rate of 60% and annealing) had a suitable combination of strength (tensile strength of 980 MPa, which was much higher than cp-Ti and comparable to Ti-6Al-4V) and low modulus of elasticity (80.4 GPa) [116]. It is worth noting that the strength and modulus of elasticity of Ti-Ta alloys are very sensitive to the Ta content; the dependence of these properties on the tantalum content in the binary Ti-Ta alloy has a complex character. Thus, the elastic modulus of the alloy first decreases almost linearly with an increasing Ta content and reaches a local minimum of 69 GPa at 30% Ta, then gradually increases and reaches 88 GPa at 50% Ta, and then gradually decreases and reaches a second local minimum of 67 GPa at 70% Ta. A further increase in Ta content leads to an increase in the elastic modulus, approaching the modulus of pure Ta [117]. The opposite dependence is observed for the tensile strength: at first, with an increasing Ta content, the strength increases, and the tensile strength reaches the first local maximum (595 MPa) at 30% Ta, then the strength slightly decreases to 530 MPa at 50% Ta. After that, it increases again and reaches the peak value of 690 MPa at 60% Ta; a further increase in Ta content slightly decreases the strength of the alloys [117]. The authors of [117] attribute these changes to the influence of tantalum concentration on the structure of binary Ti-Ta alloys (in their study, the alloys had a hexagonal (α’) martensitic structure with a Ta content of up to 20%, orthorhombic (α”) martensitic structure at a Ta content from 30 to 50%, (α” +β)-structure in the alloys with 60% Ta, and single-phase metastable β structure at a Ta content of more than 60%). In addition to tantalum concentration, the structure and, consequently, the properties of binary Ti-Ta alloys (by changing the phase composition and their ratio) are affected by the hardening heat treatment and plastic deformation (as confirmed by studies [117]).

In addition, Ti-Ta alloys have high biocompatibility and corrosion resistance. Thus, the results of a study [118] have confirmed that the corrosion resistance of Ti-Ta alloys with tantalum contents of 30, 40, 50 and 60 wt.% are not inferior to that of the Ti-6Al-7Nb alloy, and in fluorinated acidified saliva, even exceed it, which can be explained by the formation of Ta2O5 oxide film on the surface of a Ti-Ta alloy. At the same time, the authors of another study [119] state that a minimum of 40 wt.% Ta is recommended to achieve excellent corrosion properties in Ti-Ta alloys.

Tantalum also exhibits antibacterial activity against various pathogens such as Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli [120][121], so further studies on the antibacterial activity of Ti-Ta alloys are needed.

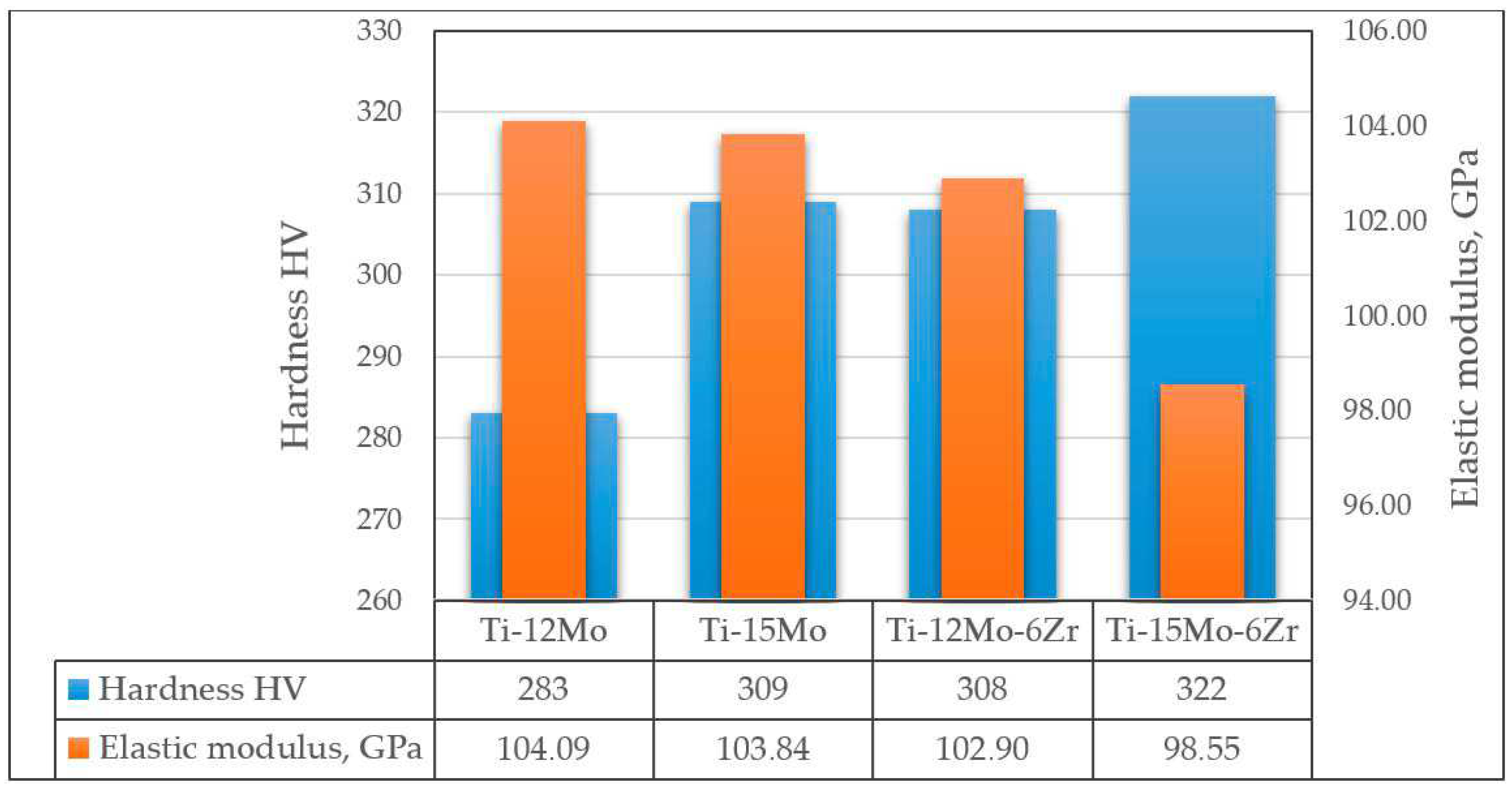

As mentioned above, molybdenum acts as a strong β-stabilizer, which reduces the elastic modulus and increases the corrosion resistance of binary Ti-Mo alloys. Thus, Ti-Mo alloys with Mo content of up to 12% have lower elastic moduli than cp-Ti (138.56 GPa) [122]. However, the character of the influence of Mo concentration (in the concentration range from 3.2 to 12 at.%) on the elastic modulus of the alloy is identical to that of tantalum: the first local minimum corresponds to the Ti-3.2Mo alloy (83.8 GPa), the local maximum to Ti-6Mo (112.092 GPa), and the second local minimum to Ti-8Mo (82.98 GPa). It is worth noting that a significant increase in the elastic modulus between Ti-4.5Mo and Ti-6Mo alloys is observed when the Mo content increases up to 6 at.%, then its value falls sharply when the Mo content increases from 6 to 8 at.%, and when the Mo content changes from 8 to 12 at.%, only a slow increase is observed [122]. A further increase in the amount of molybdenum in binary alloys, as well as their additional alloying with zirconium, leads to an increase in the amount of β-phase in the alloy structure, which contributes to an even greater decrease in the elastic modulus while maintaining the increased strength of the alloy. In [123], it was shown that the ratios of α/β-phase (in %) for Ti-12Mo, Ti-15Mo, Ti-12Mo-6Zr, and Ti-15Mo-6Zr alloys were 53.7/46.3, 50.61/49.39, 40.03/59.97, and 16.26/83.74, respectively. This also led to an increase in the hardness of the alloys and the elastic modulus of the alloys (Figure 7).

Figure 7. Hardness and elastic modulus of Ti-Mo and Ti-Mo-Zr alloys according to data.

The introduction of Fe into the ternary alloy of the Ti-Mo-Zr system reduces the elastic modulus of the alloy (from 105 GPa to 93 GPa with the addition of Fe from 1 to 3% [124]), while Ti-Mo-Zr-Fe alloys (containing from 1 to 4% Fe) are pseudo-β-alloys, i.e., the structure of the alloys contains up to 99% of the β-phase, the grain size of which decreases with increasing iron content [124].

Ti-Cu alloys are promising antibacterial biomaterials that have the potential to be tools against peri-implantitis and antibiotic resistance [125]. It was found that by varying the Cu concentration (1 to 10 wt.%) and aging temperature, the antibacterial properties of Ti-Cu alloys could be controlled. Thus, the best antibacterial properties were observed in the alloy with the maximum Cu content, Ti-10Cu, which was aged at 400 °C for 6 h [125], which may have been due to the high content of Ti2Cu in the aged alloy and, as a consequence, a higher rate of release of Cu ions. It is worth noting that this alloy was the only material that showed an antibacterial effect after two hours of testing, while after six hours, bacteria were destroyed in all alloys with a Cu content of more than 5 wt.%.

Ti-Mg alloys have a low modulus of elasticity while maintaining the high specific strength and corrosion resistance inherent in cp-Ti (while the corrosion resistance and compressive modulus of Ti-Mg alloys decrease with increasing amounts of Mg) [126][127][128]. Moreover, Mg can dissolve in the modeled body fluids and contribute to the formation of a calcium phosphate layer; after the degradation of Mg, it is possible to obtain a porous titanium framework that promotes bone sprouting into the implant volume, i.e., the osseointegration and bioactivity of the implant are increased [128].

The introduction of Sr slows down the degradation rate of Ti-Mg alloys and increases their biocompatibility and bioactivity [129]. Sr promotes bone tissue regeneration and osteointegration at the interface (bone–implant), stimulates protein amalgamation, prevents osteoporosis, and suppresses bone resorption.

The alloys of the Ti-Mg-Sr system showed high mechanical properties in comparison with traditional alloys (cp-Ti, Ti-Al-V). Thus, the Ti-10Mg-20Sr alloy showed a low elastic modulus of 36 ± 7 GPa (measured by nanoindentation) with a hardness of 1.8 ± 0.8 GPa [129].

The addition of calcium to both titanium as well as noble metals (in particular, Pd, Pt) leads to an increase in the corrosion resistance of the binary alloys Ti-Ca, Ti-Pt, and Ti-Pd in acidic fluoride aqueous solutions (e.g., HF + NaF) adapted to different pH values (from 4.7 to 3.4) [130]. This was confirmed in a study [131], where it was shown that titanium alloys Ti-0.2Pd and Ti-0.3Mo-0.8Ni exhibited higher corrosion resistance than cp-Ti at fluoride concentrations below 0.002 M due to the accelerating effect of Pd and Ni on the cathodic process and the inhibiting effect of Mo on the anodic process.

In addition, the introduction of calcium and palladium into the composition of a titanium alloy contributes to the improvement of the osteointegration of the alloy. Thus, after 60 days of exposure to immersion in SBF solution with the addition of bovine serum albumin (0.8 g/l), precipitated CaP compounds (with Ca:P ratios from 1:0.7 to 1:4.4) were found on the surfaces of Ti-0.2Pd alloy samples [132].

Thus, alloying titanium alloys with β-stabilizers (Nb, Mo, Zr (for triple and more alloys), Fe, etc.) leads to a significant decrease in the elastic modulus and increase in the strength of alloys in comparison with traditional commercially available alloys (cp-Ti, Ti-6Al-4V), but it is not enough (the minimum elastic modulus of titanium alloys is 40–50 GPa, and that of bone is 4–30 GPa). The further reduction of Young’s modulus is possible by creating porous structures with pore sizes of 100–500 μm for better ingrowth of new bone tissue [127][133]. The prospectivity of this has been supported by some studies. For example, it has been shown [127] that porous Ti fabricated using the high-pressure solid-state sintering (HPSSS) method has a high strength (~115 MPa), relatively low Young’s modulus (~18 GPa), excellent ductility, and suitable pore sizes (50–300 μm), which make it attractive for load-bearing implant applications. Meanwhile, the strength of porous titanium can also be improved by alloying with Mo and Nb. Thus, porous alloy Ti-12.5Mo, with a porosity of 40–45%, and alloy Ti-25Nb, with a porosity of 39–48%, sintered at 1050 °C for 2 h, have excellent properties close to the properties of human cortical bone (Young’s modulus is in the range of 5–18 GPa, with compressive strength in the range of 141–286 MPa), which correspond to the properties of bone [134]. In addition, in the study, the compressive strength and Young’s modulus increased linearly with the decreasing porosity of the samples.

2.2. Zirconium and Its Alloys

In modern practice zirconium, and its alloys are used for dental implant manufacturing [135][136][137][138][139][140]. Comparing the values of the electrode potentials of titanium (-1.63 mV) and zirconium (-1.4 mV), it can be assumed that implants based on zirconium alloy are more preferable, which is due to the negative influence of the negative potential of the implantation material surface on the surrounding tissues [141]. The higher the negative value of the standard electrode potential of a metal is, the greater its solubility and reactivity will be [142].

The conducted analysis of the results of the above-mentioned search query has shown that two groups of zirconium-based alloys are used for dental implant manufacturing:

-

Ceramic materials based on zirconium dioxide:

- ◦

- ◦

- ◦

- ◦

Zirconium is a rather soft gray metal, but it has a lower modulus of elasticity (92 GPa), better corrosion resistance than Ti [168], and good biocompatibility and osteoinductivity [169]. Zr, similar to titanium, is allotropic. Therefore, metal alloys based on it (in particular, Zr-Nb) belong to the group of alloys with solid-solution hardening and differ from intermetallic alloys, i.e., those inclined to magnetization, which include titanium, based on the high characteristics of fatigue endurance that do not depend much on the metal structure [141].

In [145], the microstructure and mechanical properties of cast Zr-(0-24)Nb alloys were investigated. It was found that when Nb was introduced in small amounts (up to 6 wt.%), Zr-Nb alloys consisting mainly of α’-phase (containing less than 6 wt.% Nb) showed the highest strength (786–881 MPa), moderate ductility (6.5–3.7%), and relatively high Young’s modulus (74 GPa) while maintaining low magnetic susceptibility. A further increase in niobium content led to a decrease in alloy strength (tensile strength of Zr-22Nb alloy was 605 MPa), which was associated with both the appearance of ω-phase as well as an increase in the amount of a less strong β-phase. It is worth noting that Young’s modulus of Zr-Nb alloys at a niobium concentration of up to 24% (over the whole investigated range) was lower than the elastic modulus of the titanium alloy Ti-6Al-4V, with the minimum value of Young’s modulus (48.4 GPa) being associated with alloy Zr-20Nb. Although the strength of this alloy was inferior to that of the Ti-6Al-4V alloy (687 MPa vs. 994 MPa), its value exceeded that of bone strength, and the magnetic susceptibility of the Zr-20Nb alloy was half that of the Ti-6Al-4V alloys, making it a preferred implant material for patients requiring MRI studies [145].

As mentioned above, zirconium and titanium have close atomic sizes and allotropic transformation temperatures, which allows these elements to form solid solutions of unlimited solubility. The properties of binary alloys Ti-xZr (where x is up to 90 at.%) have been discussed in detail above. Let us only add that metallic zirconium has excellent corrosion resistance in acid or alkali solutions but is subject to localized corrosion in media containing chloride or fluoride. The introduction of titanium into the alloy composition reduces the local corrosion of Zr-Ti alloys (while increasing the titanium content contributes to a decrease in the corrosion rates of the alloys), but their resistance to pitting corrosion is still inferior to that of cp-Ti [146]. Zr-20Ti and Zr-40Ti alloys exhibit good mechanical properties (the ultimate strength values are 1630 MPa and 1884 Mpa, and the microhardness values are 330 HV and 340 HV, respectively) and good machinability in cold deformation (alloy deformations at fracture are 25.2% and 26.8%, respectively) [146].

Binary Zr-Ti alloys have a predominantly α-crystalline structure, and the introduction of molybdenum, which is a β-stabilizer, leads to a change in the alloy structure. With the gradual addition of Mo from 0 to 12.5 wt.%, the phase composition of the alloys changes as α → α + β → β, with the amount of β-phase increasing with the increasing Mo content [135]. The properties of Zr-Ti-Mo alloys fully meet the requirement of aligning with the mechanical properties of biomedical dental implants. Thus, the alloys Zr-25Ti-xMo (where x is from 0 to 12.5 wt.%) have a reduced compressive strength in the range of 1154.4 to 1310.8 MPa, yield strength of 673.2 to 996.0 MPa, and Young’s modulus of 17.74 to 24.44 GPa, and the alloy Zr-25Ti-7.5Mo shows the best wear and corrosion resistance [135].

The introduction of Nb into the composition of Zr-Ti alloys also leads to the change of its structure to the β-type. Thus, the microstructure of the cast Zr-19Ti-21,4Nb alloy is represented by β-grains of 150–200 μm in size. The mechanical properties of this alloy in the deformed state correspond to the properties of the Ti-6Al-4V alloy (the tensile strength of the Zr-19Ti-21,4Nb alloy was 850–900 MPa, and the deformation of the alloy at fracture, characterizing plasticity, was 10.5%), but the modulus of elasticity is much closer to that of natural bone (37.6 GPa) [150]. The experiment with cell cultivation demonstrated the adequate adhesion of osteoblasts on the first day to both sr-Ti and Zr-Ti-Nb alloys, with subsequent proliferation on days 3 and 7. These data indicate the biocompatibility of Zr-19Ti-21,4Nb alloy and the absence of toxicity to cells [150].

The introduction of silver (6%) into Zr-Ti alloys leads to increased resistance to electrochemical corrosion (in particular, in artificial saliva containing fluorine). Moreover, the effect of Ag is stronger the more titanium is in the alloy composition since the joint action of titanium and silver promotes the formation of a thick, compact, and stable passive film [146]. At the same time, silver slightly changes the mechanical properties of Zr-xTi alloys. Thus, in a study, the introduction of 6% Ag increased the hardness of the Zr-20Ti alloy from HV 329 to HV 338, and the hardness of the Zr-40Ti alloy increased from HV 340 to HV 349 [146].

The Zr-30Ta and Zr-25Ta-5Ti alloys also showed improved biocompatibility and osteogenic activity in comparison with cp-Ti due to, among other things, favorable surface properties (increased surface hydrophilicity and roughness) [9]. Thus, the Zr-25Ta-5Ti alloy had the smallest contact angle (~30.6°) and the largest roughness value (Ra = 34.8 nm) while, for the Zr-30Ta alloy, the values of the contact angle of wettability and roughness were 46.6° and 20.7 nm, respectively (for comparison, these characteristics for cp-Ti were 52° and 13.1 nm). The differences between the samples were statistically significant (p < 0.01). In addition, the Zr-30Ta and Zr-25Ta-5Ti alloys also induced the balanced expression of M1 and M2 macrophage phenotypes during the first 24 h. A Zr-25Ta-5Ti sample adsorbed three times more protein ((147.4± 13.26) μg) compared to Zr-30Ta ((32.1 ± 4.57) μg) and CP-Ti ((32.4 ± 3.7) μg) samples.

Unlike metallic zirconia, ZrO2, zirconium dioxide, is an ultra-hard material; at the same time, it has a white color similar to that of the natural tooth root, which is favorable for restorations in the smile area [153], and it is biocompatible, does not provoke allergies, and is one of the most durable in service [141]. The zirconia surface is poorly adhered to by bacteria (40% less adhesion than metals) [170][171], and ceramic materials are less prone to plaque accumulation than metal substrates [167].

References

- Global Oral Health Status Report: Towards Universal Health Coverage for Oral Health by 2030. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240061484 (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Follow-Up to the Political Declaration of the Third High-Level Meeting of the General Assembly on the Prevention and Control of Noncommunicable Diseases. Available online: https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA75/A75_10Add1-ru.pdf (accessed on 15 August 2023). (In Russian).

- Russian Nanotitanium for Bioimplants Has No Analogues in the World. Available online: https://new.ras.ru/activities/news/rossiyskiy-nanotitan-dlya-bioimplantatov-ne-imeet-analogov-v-mire (accessed on 15 August 2023). (In Russian).

- Global Dental Implants Market by Design, Type, Price, Procedure, Material, Component, End User—Cumulative Impact of COVID-19, Russia Ukraine Conflict, and High Inflation—Forecast 2023–2030. Available online: https://www.researchandmarkets.com/report/dental-implant#reld0-4620505 (accessed on 15 August 2023).

- Dental Implants Market—Growth, Trends, COVID-19 Impact and Forecasts (2023–2028). Available online: https://www.mordorintelligence.com/ru/industry-reports/dental-implants-market (accessed on 24 August 2023).

- Thalji, G.; Cooper, L.F. Molecular assessment of osseointegration in vitro: A review of current literature. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2014, 29, 171–199.

- Yuan, K.; Chan, Y.-J.; Kung, K.-C.; Lee, T.-M. Comparison of Osseointegration on Various Implant Surfaces After Bacterial Contamination and Cleaning: A Rabbit Study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2014, 29, 32–40.

- Yao, L.; Al-Bishari, A.M.; Shen, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, T.; Sheng, L.; Wu, G.; Lu, L.; Xu, L.; Liu, J. Osseointegration and anti-infection of dental implant under osteoporotic conditions promoted by gallium oxide nano-layer coated titanium dioxide nanotube arrays. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 22961–22969.

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, H.; Juaim, A.N.; Chen, X.; Lu, C.; Zou, L.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, X. Biocompatibility and osteogenic activity of Zr–30Ta and Zr–25Ta–5Ti sintered alloys for dental and orthopedic implants. Trans. Nonferrous Met. Soc. China 2023, 33, 851–864.

- Wang, S.; Zhao, X.; Hsu, Y.; He, Y.; Wang, F.; Yang, F.; Yan, F.; Xia, D.; Liu, Y. Surface modification of titanium implants with Mg-containing coatings to promote osseointegration. Acta Biomater. 2023, 169, 19–44.

- Gaur, S.; Chugh, A.; Chaudhry, K.; Bajpayee, A.; Jain, G.; Chugh, V.K.; Kumar, P.; Singh, S. Efficacy and Safety of Concentrated Growth Factors and Platelet- Rich Fibrin on Stability and Bone Regeneration in Patients with Immediate Dental Implants: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2022, 37, 784–792.

- Han, C.-H.; Kim, S.; Chung, M.-K.; Heo, S.-J.; Rhyu, I.-C.; Kwon, Y.; Chang, J.-S. Regenerated Bone Pattern Around Exposed Implants with Various Designs. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2019, 34, 61–67.

- Bang, S.-M.; Moon, H.-J.; Kwon, Y.-D.; Yoo, J.-Y.; Pae, A.; Kwon, I.K. Osteoblastic and osteoclastic differentiation on SLA and hydrophilic modified SLA titanium surfaces. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2014, 25, 831–837.

- Alavi, S.E.; Alavi, S.Z.; Gholami, M.; Sharma, A.; Sharma, L.A.; Shahmabadi, H.E. Biocomposite-based strategies for dental bone regeneration. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2023, in press.

- Tangri, S.; Hasan, N.; Kaur, J.; Mohammad, F.; Maan, S.; Kesharwani, P.; Ahmad, F.J. Drug loaded bioglass nanoparticles and their coating for efficient tissue and bone regeneration. J. Non-Cryst. Solids 2023, 616, 122469.

- Shi, C.; Gao, J.; Wang, M.; Fu, J.; Wang, D.; Zhu, Y. Ultra-trace silver-doped hydroxyapatite with non-cytotoxicity and effective antibacterial activity. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2015, 55, 497–505.

- Li, Y.; Liu, X.; Tan, L.; Cui, Z.; Yang, X.; Yeung, K.W.K.; Pan, H.; Wu, S. Construction of N-halamine labeled silica/zinc oxide hybrid nanoparticles for enhancing antibacterial ability of Ti implants. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2017, 76, 50–58.

- Li, M.; Liu, Q.; Jia, Z.; Xu, X.; Shi, Y.; Cheng, Y.; Zheng, Y. Polydopamine-induced nanocomposite Ag/CaP coatings on the surface of titania nanotubes for antibacterial and osteointegration functions. J. Mater. Chem. B 2015, 45, 8796–8805.

- Lung, C.Y.K.; Khan, A.S.; Zeeshan, R.; Akhtar, S.; Chaudhry, A.A.; Matinlinna, J.P. An antibacterial porous calcium phosphate bilayer functional coatings on titanium dental implants. Ceram. Int. 2023, 49, 2401–2409.

- Andrade del Olmo, J.; Pérez-Álvarez, L.; Sáez Martínez, V.; Benito Cid, S.; Ruiz-Rubio, L.; Pérez González, R.; Vilas-Vilela, J.L.; Alonso, J.M. Multifunctional antibacterial chitosan-based hydrogel coatings on Ti6Al4V biomaterial for biomedical implant applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2023, 231, 123328.

- Zhao, Z.; Wan, Y.; Yu, M.; Wang, H.; Cai, Y.; Liu, C.; Zhang, D. Biocompability evaluation of micro textures coated with zinc oxide on Ti-6Al-4V treated by nanosecond laser. Surf. Coat. Technol. 2021, 422, 127453.

- Hashim, N.C.; Nordin, D. Nano-Hydroxyapatite Powder for Biomedical Implant Coating. Mater. Today 2019, 19, 1562–1571.

- Mishra, S.; Chowdhary, R. PEEK materials as an alternative to titanium in dental implants: A systematic review. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2019, 21, 208–222.

- Zou, R.; Bi, L.; Huang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Li, L.; Liu, J.; Feng, L.; Jiang, X.; Deng, B. A biocompatible silicon nitride dental implant material prepared by digital light processing technology. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. 2023, 141, 105756.

- Jayasree, R.; Raghava, K.; Sadhasivam, M.; Srinivas, P.V.V.; Vijay, R.; Pradeep, K.G.; Rao, T.N.; Chakravarty, D. Bi-layered metal-ceramic component for dental implants by spark plasma sintering. Mater. Lett. 2023, 344, 134403.

- Zagorsky, V.A. Dental implantation. Materials and components. Symb. Sci. 2016, 9, 132–136. (In Russian)

- Jae-Hyun, L.; Kim, J.C.; Kim, H.-Y.; Yeo, I.-S.L. Influence of Connections and Surfaces of Dental Implants on Marginal Bone Loss: A Retrospective Study Over 7 to 19 Years. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2020, 35, 1195–1202.

- Canullo, L.; Peñarrocha, D.; Clementini, M.; Iannello, G.; Micarelli, C. Impact of plasma of argon cleaning treatment on implant abutments in patients with a history of periodontal disease and thin biotype: Radiographic results at 24-month follow-up of a RCT. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2015, 26, 8–14.

- Ding, L.; Zhang, P.; Wang, X.; Kasugai, S. A doxycycline-treated hydroxyapatite implant surface attenuates the progression of peri-implantitis: A radiographic and histological study in mice. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2019, 21, 154–159.

- Fraser, D.; Mendonca, G.; Sartori, E.; Funkenbusch, P.; Ercoli, C.; Meirelles, L. Bone response to porous tantalum implants in a gap-healing model. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2019, 30, 156–168.

- Anchieta, R.B.; Baldassarri, M.; Guastaldi, F.; Tovar, N.; Janal, M.N.; Gottlow, J.; Dard, M.; Jimbo, R.; Coelho, P.G. Mechanical property assessment of bone healing around a titanium-zirconium alloy dental implant. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2014, 16, 913–919.

- Alves, S.A.; Rossi, A.L.; Ribeiro, A.R.; Toptan, F.; Pinto, A.M.; Shokuhfar, T.; Celis, J.-P.; Rocha, L.A. Improved tribocorrosion performance of bio-functionalized TiO2 nanotubes under two-cycle sliding actions in artificial saliva. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. 2018, 80, 143–154.

- Oh, J.-S.; Seo, Y.-S.; Lee, G.-J.; You, J.-S.; Kim, S.-G. A comparative study with biphasic calcium phosphate and deproteinized bovine bone in maxillary sinus augmentation: A prospective randomized controlled clinical trial. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2019, 34, 233–242.

- Jiang, Q.-H.; Gong, X.; Wang, X.-X.; He, F.-M. Osteogenesis of rat mesenchymal stem cells and osteoblastic cells on strontium-doped nanohydroxyapatite-coated titanium surfaces. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2015, 30, 461–471.

- Hunziker, E.B.; Spiegl-Habegger, M.; Rudolf, S.; Liu, Y.; Gu, Z.; Lippuner, K.; Shintani, N.; Enggist, L. A novel experimental dental implant permits quantitative grading of surface-property effects on osseointegration. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2018, 33, 967–978.

- Fardjahromi, M.A.; Ejeian, F.; Razmjou, A.; Vesey, G.; Mukhopadhyay, S.C.; Derakhshan, A.; Warkiani, M.E. Enhancing osteoregenerative potential of biphasic calcium phosphates by using bioinspired ZIF8 coating. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2021, 123, 111972.

- Bryington, M.; Mendonça, G.; Nares, S.; Cooper, L.F. Osteoblastic and cytokine gene expression of implant-adherent cells in humans. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2014, 25, 52–58.

- Zhou, C.; Ge, Z.; Song, L.; Yan, J.; Lang, X.; Zhang, Y.; He, F. Strontium-modified titanium substrate promotes osteogenic differentiation of MSCs and implant osseointegration via upregulating CDH2. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2023, 34, 297–311.

- Mehl, C.; Gaßling, V.; Schultz-Langerhans, S.; Açil, Y.; Bähr, T.; Wiltfang, J.; Kern, M. Influence of four different abutment materials and the adhesive joint of two-piece abutments on cervical implant bone and soft tissue. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2016, 31, 1264–1272.

- Chappuis, V.; Cavusoglu, Y.; Gruber, R.; Kuchler, U.; Buser, D.; Bosshardt, D.D. Osseointegration of Zirconia in the Presence of Multinucleated Giant Cells. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2016, 18, 686–698.

- Zavan, B.; Ferroni, L.; Gardin, C.; Sivolella, S.; Piattelli, A.; Mijiritsky, E. Release of VEGF from dental implant improves osteogenetic process: Preliminary in vitro tests. Materials 2017, 10, 1052.

- Gross, M.D. Occlusion in implant dentistry. A review of the literature of prosthetic determinants and current concepts. Aust. Dent. J. 2008, 53 (Suppl. 1), S60–S68.

- Mishra, S.K.; Chowdhary, R.; Chrcanovic, B.R.; Brånemark, P.-I. Osseoperception in Dental Implants: A Systematic Review. J. Prosthodont. 2016, 25, 185–195.

- González-Gil, D.; Dib-Zaitun, I.; Flores-Fraile, J.; López-Marcos, J. Active Tactile Sensibility in Implant Prosthesis vs. Complete Dentures: A Psychophysical Study. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 6819.

- Toledano-Serrabona, J.; Sánchez-Garcés, M.Á.; Gay-Escoda, C.; Valmaseda-Castellón, E.; Camps-Font, O.; Verdeguer, P.; Molmeneu, M.; Gil, F.J. Mechanical properties and corrosion behavior of Ti6Al4V particles obtained by implantoplasty: An in vitro study. Part II. Materials 2021, 14, 6519.

- Sikora, C.L.; Alfaro, M.F.; Yuan, J.C.-C.; Barao, V.A.; Sukotjo, C.; Mathew, M.T. Wear and Corrosion Interactions at the Titanium/Zirconia Interface: Dental Implant Application. J. Prosthodont. 2018, 27, 842–852.

- Revathi, A.; Borrás, A.D.; Muñoz, A.I.; Richard, C.; Manivasagam, G. Degradation mechanisms and future challenges of titanium and its alloys for dental implant applications in oral environment. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2017, 76, 1354–1368.

- Weller, J.; Vasudevan, P.; Kreikemeyer, B.; Ekat, K.; Jackszis, M.; Springer, A.; Chatzivasileiou, K.; Lang, H. The role of bacterial corrosion on recolonization of titanium implant surfaces: An in vitro study. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2022, 24, 664–675.

- Silva, M.D.; Walton, T.R.; Alrabeah, G.O.; Layton, D.M.; Petridis, H. Comparison of corrosion products from implant and various golad-based abutment couplings: The effect of gold plating. J. Oral. Implant. 2021, 47, 370–379.

- Eliaz, N. Corrosion of metallic biomaterials: A review. Materials 2019, 12, 407.

- Trezubov, V.N.; Mishnev, L.M.; Zhulev, E.N.; Trezubov, V.V. Orthopedic Dentistry. Applied Materials Science, 7th ed.; MED Press-inform: Moscow, Russia, 2017; 328p.

- Grigoriev, S.; Sotova, C.; Vereschaka, A.; Uglov, V.; Cherenda, N. Modifying Coatings for Medical Implants Made of Titanium Alloys. Metals 2023, 13, 718.

- Falanga, A.; Laheurte, P.; Vahabi, H.; Tran, N.; Khamseh, S.; Saeidi, H.; Khodadadi, M.; Zarrintaj, P.; Saeb, M.R.; Mozafari, M. Niobium-treated titanium implants with improved cellular and molecular activities at the tissue-implant interface. Materials 2019, 12, 3861.

- Fintová, S.; Dlhý, P.; Mertová, K.; Chlup, Z.; Duchek, M.; Procházka, R.; Hutař, P. Fatigue properties of UFG Ti grade 2 dental implant vs. conventionally tested smooth specimens. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. 2021, 123, 104715.

- Monetta, T.; Acquesta, A.; Bellucci, F. Evaluation of roughness and electrochemical behavior of titanium in biological environment. Metall. Ital. 2014, 106, 13–21.

- Laurindo, C.A.H.; Torres, R.D.; Mali, S.A.; Gilbert, J.L.; Soares, P. Incorporation of Ca and P on anodized titanium surface: Effect of high current density. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2014, 37, 223–231.

- Babuska, V.; Palan, J.; Dobra, J.K.; Kulda, V.; Duchek, M.; Cerny, J.; Hrusak, D. Proliferation of osteoblasts on laser-modified nanostructured titanium surfaces. Materials 2018, 11, 1827.

- Fintová, S.; Kuběna, I.; Palán, J.; Mertová, K.; Duchek, M.; Hutař, P.; Pastorek, F.; Kunz, L. Influence of sandblasting and acid etching on fatigue properties of ultra-fine grained Ti grade 4 for dental implants. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. 2020, 111, 104016.

- Wennerberg, A.; Jimbo, R.; Stübinger, S.; Obrecht, M.; Dard, M.; Berner, S. Nanostructures and hydrophilicity influence osseointegration: A biomechanical study in the rabbit tibia. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2014, 25, 1041–1050.

- Jacobs, N.; Seghi, R.; Johnston, W.M.; Yilmaz, B. Displacement and performance of abutments in narrow-diameter implants with different internal connections. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 127, 100–106.

- Catauro, M.; Bollino, F.; Papale, F.; Pacifico, S. Modulation of indomethacin release from ZrO2/PCL hybrid multilayers synthesized via solegel dip coating. J. Drug Deliv. Sci. Technol. 2015, 26, 10–16.

- Moghaddam, N.S.; Skoracki, R.; Miller, M.; Elahinia, M.; Dean, D. Three Dimensional Printing of Stiffness-tuned, Nitinol Skeletal Fixation Hardware with an Example of Mandibular Segmental Defect Repair. Procedia CIRP 2016, 49, 45–50.

- Mastrangelo, F.; Quaresima, R.; Abundo, R.; Spagnuolo, G.; Marenzi, G. Esthetic and physical changes of innovative titanium surface properties obtained with laser technology. Materials 2020, 13, 1066.

- Szmukler-Moncler, S.; Blus, C.; Schwarz, D.M.; Orrù, G. Characterization of a macro-and micro-textured titanium grade 5 alloy surface obtained by etching only without sandblasting. Materials 2020, 13, 5074.

- Ghensi, P.; Bettio, E.; Maniglio, D.; Bonomi, E.; Piccoli, F.; Gross, S.; Caciagli, P.; Segata, N.; Nollo, G.; Tessarolo, F. Dental implants with anti-biofilm properties: A pilot study for developing a new sericin-based coating. Materials 2019, 12, 2429.

- Di Giulio, M.; Traini, T.; Sinjari, B.; Nostro, A.; Caputi, S.; Cellini, L. Porphyromonas gingivalis biofilm formation in different titanium surfaces, an in vitro study. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2016, 27, 918–925.

- Sancar, B.; Dayı, E. Evaluation of metal concentrations in hair and nails after dental implant placement. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 128, 625–631.

- More than Solid—Roxolid®. Reducing Invasiveness. Straumann® Roxolid®. Available online: https://www.straumann.com/content/dam/media-center/straumann/en/documents/interactive-sales-presentation/490.137-en_low.pdf (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- El Chaar, E.; Zhang, L.; Zhou, Y.; Sandgren, R.; Fricain, J.-C.; Dard, M.; Pippenger, B.; Catros, S. Osseointegration of superhydrophilic implants placed in defect grafted bones. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2019, 34, 443–450.

- Lotz, E.M.; Olivares-Navarrete, R.; Hyzy, S.L.; Berner, S.; Schwartz, Z.; Boyan, B.D. Comparable responses of osteoblast lineage cells to microstructured hydrophilic titanium–zirconium and microstructured hydrophilic titanium. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2017, 28, e51–e59.

- Xiao, W.; Chen, Y.; Chu, C.; Dard, M.M.; Man, Y. Influence of implant location on titanium-zirconium alloy narrow-diameter implants: A 1-year prospective study in smoking and nonsmoking populations. J. Prosthet. Dent. 2022, 128, 159–166.

- Mishra, S.K.; Chowdhary, R. Evolution of dental implants through the work of per-ingvar branemark: A systematic review. Indian J. Dent. Res. 2020, 31, 930–956.

- Caparrós, C.; Ortiz-Hernandez, M.; Molmeneu, M.; Punset, M.; Calero, J.A.; Aparicio, C.; Fernández-Fairén, M.; Perez, R.; Gil, F.J. Bioactive macroporous titanium implants highly interconnected. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2016, 27, 151.

- Liens, A.; Etiemble, A.; Rivory, P.; Balvay, S.; Pelletier, J.-M.; Cardinal, S.; Fabrègue, D.; Kato, H.; Steyer, P.; Munhoz, T.; et al. On the potential of Bulk Metallic Glasses for dental implantology: Case study on Ti40Zr10Cu36Pd14. Materials 2018, 11, 249.

- Li, P.; Ma, X.; Tong, T.; Wang, Y. Microstructural and mechanical properties of β-type Ti–Mo–Nb biomedical alloys with low elastic modulus. J. Alloys Compd. 2020, 815, 152412.

- Ozan, S.; Lin, J.; Li, Y.; Ipek, R.; Wen, C. Development of Ti–Nb–Zr alloys with high elastic admissible strain for temporary orthopedic devices. Acta Biomater. 2015, 20, 176–187.

- Hua, F.; Mon, K.; Pasupathi, P.; Gordon, G.; Shoesmith, D. A review of corrosion of titanium grade 7 and other titanium alloys in nuclear waste repository environments. Corrosion 2005, 61, 987–1003.

- Steinemann, S.G.; Perren, S.M. Titanium alloys as metallic biomaterials. In Proceedings of the Fifth World Conference On Titanium, Munich, Germany, 10–14 September 1984; Volume 2, pp. 1327–1334.

- Sidelnikov, A.I. Comparative characteristics of materials of the titanium group used in the production of modern dental implants. InfoDENT 2000, 5, 10–12.

- Mirza, A.; King, A.; Troakes, C.; Exley, C. Aluminium in brain tissue in familial Alzheimer’s disease. J. Trace Elem. Med. Biol. 2017, 40, 30–36.

- Cremasco, A.; Messias, A.D.; Esposito, A.R.; Duek, E.A.R.; Caram, R. Effects of alloying elements on the cytotoxic response of titanium alloys. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2011, 31, 833–839.

- Lin, C.-W.; Ju, C.-P.; Lin, J.-H.C. A comparison of the fatigue behavior of cast Ti–7.5Mo with c.p. titanium, Ti–6Al–4V and Ti–13Nb–13Zr alloys. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 2899–2907.

- Cardoso, G.C.; de Almeida, G.S.; Corrêa, D.O.G.; Zambuzzi, W.F.; Buzalaf, M.A.R.; Correa, D.R.N.; Grandini, C.R. Preparation and characterization of novel as-cast Ti-Mo-Nb alloys for biomedical applications. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11874.

- Albrektsson, T.; Hansson, H.A.; Ivarsson, B. Interface analysis of titanium and zirconium bone implants. Biomaterials 1985, 6, 97–101.

- Boehlert, C.J.; Cowen, C.J.; Quast, J.P.; Akahori, T.; Niinomi, M. Fatigue and wear evaluation of Ti-Al-Nb alloys for biomedical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2008, 28, 323–330.

- Msweli, N.P.; Akinwamide, S.O.; Olubambi, P.A.; Obadele, B.A. Microstructure and biocorrosion studies of spark plasma sintered yttria stabilized zirconia reinforced Ti6Al7Nb alloy in Hanks’ solution. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2023, 293, 126940.

- Eisenbarth, E.; Velten, D.; Müller, M.; Thull, R.; Breme, J. Biocompatibility of β-stabilizing elements of titanium alloys. Biomaterials 2004, 25, 5705–5713.

- Huang, H.-H.; Tung, K.-L.; Lin, Y.-Y. Treating Ti containing dental orthodontic wires with nitrogen plasma immersion ion implantation to reduce the metal ions release and bacterial adhesion. Mater. Technol. 2015, 30, B73–B79.

- Okazaki, Y.; Gotoh, E. Comparison of metal release from various metallic biomaterials in vitro. Biomaterials 2005, 26, 11–21.

- Schulze, C.; Weinmann, M.; Schweigel, C.; Keßler, O.; Bader, R. Mechanical properties of a newly additive manufactured implant material based on Ti-42Nb. Materials 2018, 11, 124.

- Fikeni, L.; Annan, K.A.; Mutombo, K.; Machaka, R. Effect of Nb content on the microstructure and mechanical properties of binary Ti-Nb alloys. Mater. Today 2021, 38, 913–917.

- Cremasco, A.; Osório, W.R.; Freire, C.M.A.; Garcia, A.; Caram, R. Electrochemical corrosion behavior of a Ti–35Nb alloy for medical prostheses. Electrochim. Acta 2008, 53, 4867–4874.

- Hoppe, V.; Szymczyk-Ziółkowska, P.; Rusińska, M.; Dybała, B.; Poradowski, D.; Janeczek, M. Assessment of mechanical, chemical, and biological properties of Ti-Nb-Zr alloy for medical applications. Materials 2021, 14, 126.

- Cordeiro, J.M.; Nagay, B.E.; Ribeiro, A.L.R.; Cruz, N.C.; Rangel, E.C.; Fais, L.M.G.; Vaz, L.G.; Barão, V.A.R. Functionalization of an experimental Ti-Nb-Zr-Ta alloy with a biomimetic coating produced by plasma electrolytic oxidation. J. Alloys Compd. 2019, 770, 1038–1048.

- Meng, X.; Wang, X.; Guo, Y.; Ma, S.; Luo, W.; Xiang, X.; Zhao, J.; Zhou, Y. Biocompatibility evaluation of a newly developed Ti-Nb-Zr-Ta-Si alloy implant. J. Biomater. Tissue Eng. 2016, 6, 861–869.

- Souza, J.G.S.; Bertolini, M.M.; Costa, R.C.; Nagay, B.E.; Dongari-Bagtzoglou, A.; Barão, V.A.R. Targeting implant-associated infections: Titanium surface loaded with antimicrobial. iScience 2021, 24, 102008.

- Sarraf, M.; Ghomi, E.R.; Alipour, S.; Ramakrishna, S.; Sukiman, N.L. A state-of-the-art review of the fabrication and characteristics of titanium and its alloys for biomedical applications. Bio-Design Manuf. 2022, 5, 371–395.

- Lemire, J.; Harrison, J.; Turner, R. Antimicrobial activity of metals: Mechanisms, molecular targets and applications. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2013, 11, 371–384.

- Alberta, L.A.; Vishnu, J.; Hariharan, A.; Pilz, S.; Gebert, A.; Calin, M. Novel low modulus beta-type Ti–Nb alloys by gallium and copper minor additions for antibacterial implant applications. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2022, 20, 3306–3322.

- Alberta, L.A.; Vishnu, J.; Douest, Y.; Perrin, K.; Trunfio-Sfarghiu, A.-M.; Courtois, N.; Gebert, A.; Ter-Ovanessian, B.; Calin, M. Tribocorrosion behavior of β-type Ti-Nb-Ga alloys in a physiological solution. Tribol. Int. 2023, 181, 108325.

- Zhao, Q.; Ueno, T.; Wakabayashi, N. A review in titanium-zirconium binary alloy for use in dental implants: Is there an ideal Ti-Zr composing ratio? Jpn. Dent. Sci. Rev. 2023, 59, 28–37.

- Correa, D.R.N.; Vicente, F.B.; Donato, T.A.G.; Arana-Chavez, V.E.; Buzalaf, M.A.R.; Grandini, C.R. The effect of the solute on the structure, selected mechanical properties, and biocompatibility of Ti–Zr system alloys for dental applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2014, 34, 354–359.

- Ho, W.-F.; Chen, W.-K.; Wu, S.-C.; Hsu, H.-C. Structure, mechanical properties, and grindability of dental Ti–Zr alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2008, 19, 3179–3186.

- Hsu, H.-C.; Wu, S.-C.; Sung, Y.-C.; Ho, W.-F. The structure and mechanical properties of as-cast Zr–Ti alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2009, 488, 279–283.

- Cordeiro, J.M.; Beline, T.; Ribeiro, A.L.R.; Rangel, E.C.; da Cruz, N.C.; Landers, R.; Faverani, L.P.; Vaz, L.G.; Fais, L.M.G.; Vicentei, F.B.; et al. Development of binary and ternary titanium alloys for dental implants. Dent. Mater. 2017, 33, 1244–1257.

- Medvedev, A.E.; Molotnikov, A.; Lapovok, R.; Zeller, R.; Berner, S.; Habersetzer, P.; Dalla Torre, F. Microstructure and mechanical properties of Ti-15Zr alloy used as dental implant material. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. 2016, 62, 384–398.

- Grandin, H.M.; Berner, S.; Dard, M. A Review of Titanium Zirconium (TiZr) Alloys for Use in Endosseous Dental Implants. Materials 2012, 5, 1348–1360.

- Hacisalihoglu, I.; Samancioglu, A.; Yildiz, F.; Purcek, G.; Alsaran, A. Tribocorrosion properties of different type titanium alloys in simulated body fluid. Wear 2015, 332–333, 679–686.

- Froes, F.H. Titanium Alloys: Thermal Treatment and Thermomechanical Processing. In Encyclopedia of Materials: Science and Technology, 2nd ed.; Buschow, K.H.J., Cahn, R.W., Flemings, M.C., Ilschner, B., Kramer, E.J., Mahajan, S., Veyssière, P., Eds.; Elsevier Ltd.: Exeter Devon, UK, 2001; pp. 9369–9373.

- Okazaki, Y.; Katsuda, S.-I. Biological safety evaluation and surface modification of biocompatible ti–15Zr–4Nb alloy. Materials 2021, 14, 731.

- Eldabah, N.M.; Shoukry, A.; Khair-Eldeen, W.; Kobayashi, S.; Gepreel, M.A.-H. Design and characterization of low Young’s modulus Ti-Zr-Nb-based medium entropy alloys assisted by extreme learning machine for biomedical applications. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 968, 171755.

- Hon, Y.-H.; Wang, J.-Y.; Pan, Y.-N. Composition/Phase Structure and Properties of Titanium-Niobium Alloys. Mater. Trans. 2003, 44, 2384–2390.

- ISO 10993; Biological Evaluation of Medical Devices. The International Organization for Standard (ISO): Geneva, Switzerland, 2010.

- Qi, P.; Li, B.; Wang, T.; Zhou, L.; Nie, Z. Microstructure and properties of a novel ternary Ti–6Zr–xFe alloy for biomedical applications. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 854, 157119.

- Trillo, E.A.; Ortiz, C.; Dickerson, P.; Villa, R.; Stafford, S.W.; Murr, L.E. Evaluation of mechanical and corrosion biocompatibility of TiTa alloys. J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Med. 2001, 12, 283–292.

- Huang, Q.; Xu, S.; Ouyang, Z.; Yang, Y.; Liu, Y. Multi-scale nacre-inspired lamella-structured Ti-Ta composites with high strength and low modulus for load-bearing orthopedic and dental applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2021, 118, 111458.

- Zhou, Y.L.; Niinomi, M.; Akahori, T. Effects of Ta content on Young’s modulus and tensile properties of binary Ti–Ta alloys for biomedical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. A-Struct. 2004, 371, 283–290.

- Mareci, D.; Chelariu, R.; Gordin, D.-M.; Ungureanu, G.; Gloriant, T. Comparative corrosion study of Ti–Ta alloys for dental applications. Acta Biomater. 2009, 5, 3625–3639.

- Mendis, S.; Xu, W.; Tang, H.P.; Jones, L.A.; Liang, D.; Thompson, R.; Choong, P.; Brandt, M.; Qian, M. Characteristics of oxide films on Ti-(10–75)Ta alloys and their corrosion performance in an aerated Hank’s balanced salt solution. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 506, 145013.

- Schildhauer, T.; Robie, B.; Muhr, G.; Köller, M. Bacterial Adherence to Tantalum Versus Commonly Used Orthopedic Metallic Implant Materials. J. Orthop. Trauma 2006, 20, 476–484.

- Wang, X.; Ning, B.; Pei, X. Tantalum and its derivatives in orthopedic and dental implants: Osteogenesis and antibacterial properties. Colloid. Surf. B 2021, 208, 112055.

- Zhang, W.; Liu, Y.; Wu, H.; Song, M.; Zhang, T.; Lan, X.; Yao, T. Elastic modulus of phases in Ti–Mo alloys. Mater. Charact. 2015, 106, 302–307.

- Mohan, P.; Rajak, D.K.; Pruncu, C.I.; Behera, A.; Amigó-Borrás, V.; Elshalakany, A.B. Influence of β-phase stability in elemental blended Ti-Mo and Ti-Mo-Zr alloys. Micron 2021, 142, 102992.

- Mohan, P.; Elshalakany, A.B.; Osman, T.A.; Amigo, V.; Mohamed, A. Effect of Fe content, sintering temperature and powder processing on the microstructure, fracture and mechanical behaviours of Ti-Mo-Zr-Fe alloys. J. Alloys Compd. 2017, 729, 1215–1225.

- Fowler, L.; Masia, N.; Cornish, L.A.; Chown, L.H.; Engqvist, H.; Norgren, S.; Öhman-Mägi, C. Development of antibacterial Ti-Cux alloys for dental applications: Effects of ageing for alloys with up to 10 wt% Cu. Materials 2019, 12, 4017.

- Tejeda-Ochoa, A.; Kametani, N.; Carreño-Gallardo, C.; Ledezma-Sillas, J.E.; Adachi, N.; Todaka, Y.; Herrera-Ramirez, J.M. Formation of a metastable fcc phase and high Mg solubility in the Ti-Mg system by mechanical alloying. Powder Technol. 2020, 374, 348–352.

- Cai, X.; Ding, S.; Li, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wen, K.; Xu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Shen, T. Simultaneous sintering of low-melting-point Mg with high-melting-point Ti via a novel one-step high-pressure solid-phase sintering strategy. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 858, 158344.

- Liu, Y.; Li, K.; Luo, T.; Song, M.; Wu, H.; Xiao, J.; Tan, Y.; Cheng, M.; Chen, B.; Niu, X.; et al. Powder metallurgical low-modulus Ti–Mg alloys for biomedical applications. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2015, 56, 241–250.

- Pradeep, N.B.; Rajath Hegde, M.M.; Rajendrachari, S.; Surendranathan, A.O. Investigation of microstructure and mechanical properties of microwave consolidated TiMgSr alloy prepared by high energy ball milling. Powder Technol. 2022, 408, 117715.

- Haruna, T. Development of Ti alloys for dental devices with corrosion resistance to fluoride solutions. Zairyo-to-Kankyo/Corros. Eng. 2014, 63, 309–315.

- Wang, Z.B.; Hu, H.X.; Zheng, Y.G.; Ke, W.; Qiao, Y.X. Comparison of the corrosion behavior of pure titanium and its alloys in fluoride-containing sulfuric acid. Corros. Sci. 2016, 103, 50–65.

- Wang, X.-L.; Zhou, Q.; Yang, K.; Zou, C.-H.; Wang, L. Performance of surface on ultrafine grained Ti-0.2Pd in simulated body fluid. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 434, 957–966.

- Issariyapat, A.; Huang, J.; Teramae, T.; Kariya, S.; Bahador, A.; Visuttipitukul, P.; Umeda, J.; Alhazaa, A.; Kondoh, K. Microstructure refinement and strengthening mechanisms of additively manufactured Ti-Zr alloys prepared from pre-mixed feedstock. Addit. Manuf. 2023, 73, 103649.

- Yang, D.; Guo, Z.; Shao, H.; Liu, X.; Ji, Y. Mechanical Properties of Porous Ti-Mo and Ti-Nb Alloys for Biomedical Application by Gelcasting. Procedia Eng. 2012, 36, 160–167.

- Wei, C.; Luo, L.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Su, S.; Zhan, Y. New Zr–25Ti–xMo alloys for dental implant application: Properties characterization and surface analysis. J. Mech. Behav. Biomed. 2020, 111, 104017.

- Ruiz Henao, P.A.; Caneiro Queija, L.; Mareque, S.; Tasende Pereira, A.; Liñares González, A.; Blanco Carrión, J. Titanium vs. ceramic single dental implants in the anterior maxilla: A 12-month randomized clinical trial. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2021, 32, 951–961.

- Siddiqi, A.; Khan, A.S.; Zafar, S. Thirty years of translational research in zirconia dental implants: A systematic review of the literature. J. Oral. Implant. 2017, 43, 314–326.

- Siddiqi, A.; Kieser, J.A.; De Silva, R.K.; Thomson, W.M.; Duncan, W.J. Soft and Hard Tissue Response to Zirconia versus Titanium One-Piece Implants Placed in Alveolar and Palatal Sites: A Randomized Control Trial. Clin. Implant Dent. Relat. Res. 2015, 17, 483–496.

- Thoma, D.S.; Ioannidis, A.; Cathomen, E.; Hämmerle, C.H.; Hüsler, J.; Jung, R.E. Discoloration of the peri-implant mucosa caused by zirconia and titanium implants. Int. J. Periodontics Restor. 2016, 36, 38–45.

- Chiou, L.-L.; Panariello, B.H.D.; Hamada, Y.; Gregory, R.L.; Blanchard, S.; Duarte, S. Comparison of In Vitro Biofilm Formation on Titanium and Zirconia Implants. BioMed Res. Int. 2023, 2023, 8728499.

- Yegorov, A.A.; Drovosekov, M.N.; Aronov, A.M.; Rozhnova, O.M.; Yegorova, O.P. Comparative characteristics of materials used in dental implantation. Bull. Sib. Med. 2014, 13, 41–47. (In Russian)

- Paraskevich, V.L. Dental Implantology: Fundamentals of Theory and Practice, 3rd ed.; Medical Information Agency LLC: Moscow, Russia, 2011; 400p. (In Russian)

- Korniienko, V.; Oleshko, O.; Husak, Y.; Deineka, V.; Holubnycha, V.; Mishchenko, O.; Kazek-Kęsik, A.; Jakóbik-Kolon, A.; Pshenychnyi, R.; Leśniak-Ziółkowska, K.; et al. Formation of a bacteriostatic surface on ZrNb alloy via anodization in a solution containing Cu nanoparticles. Materials 2020, 13, 3913.

- Oleshko, O.; Deineka, V.V.; Husak, Y.; Korniienko, V.; Mishchenko, O.; Holubnycha, V.; Pisarek, M.; Michalska, J.; Kazek-Kesik, A.; Jakóbik-Kolon, A.; et al. Ag nanoparticle-decorated oxide coatings formed via plasma electrolytic oxidation on ZrNb alloy. Materials 2019, 12, 3742.

- Kondo, R.; Nomura, N.; Suyalatu; Tsutsumi, Y.; Doi, H.; Hanawa, T. Microstructure and mechanical properties of as-cast Zr–Nb alloys. Acta Biomater. 2011, 7, 4278–4284.

- Cui, W.F.; Liu, N.; Qin, G.W. Microstructures, mechanical properties and corrosion resistance of the Zr-xTi (Ag) alloys for dental implant application. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2016, 176, 161–166.

- Akimoto, T.; Ueno, T.; Tsutsumi, Y.; Doi, H.; Hanawa, T.; Wakabayashi, N. Evaluation of corrosion resistance of implant-use Ti-Zr binary alloys with a range of compositions. J. Biomed. Mater. Res. B Appl. Biomater. 2018, 106, 73–79.

- Bolat, G.; Izquierdo, J.; Santana, J.; Mareci, D.; Souto, R.M. Electrochemical characterization of ZrTi alloys for biomedical applications. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 88, 447–456.

- Bolat, G.; Izquierdo, J.; Mareci, D.; Sutiman, D.; Souto, R.M. Electrochemical characterization of ZrTi alloys for biomedical applications. Part 2: The effect of thermal oxidation. Electrochim. Acta 2013, 106, 432–439.

- Mishchenko, O.; Ovchynnykov, O.; Kapustian, O.; Pogorielov, M. New Zr-Ti-Nb alloy for medical application: Development, chemical and mechanical properties, and biocompatibility. Materials 2020, 13, 1306.

- Michalska, J.; Sowa, M.; Stolarczyk, A.; Warchoł, F.; Nikiforow, K.; Pisarek, M.; Dercz, G.; Pogorielov, M.; Mishchenko, O.; Simka, W. Plasma electrolytic oxidation of Zr-Ti-Nb alloy in phosphate-formate-EDTA electrolyte. Electrochim. Acta 2022, 419, 140375.

- Roehling, S.; Gahlert, M.; Janner, S.; Meng, B.; Woelfler, H.; Cochran, D.L. Ligature-induced peri-implant bone loss around loaded zirconia and titanium implants. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2019, 34, 357–365.

- Bahadirli, G.; Yilmaz, S.; Jones, T.; Sen, D. Influences of implant and framework materials on stress distribution: A three-dimensional finite element analysis study. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Implant. 2018, 33, e117–e126.

- Sancho-Puchades, M.; Hämmerle, C.H.F.; Benic, G.I. In vitro assessment of artifacts induced by titanium, titanium-zirconium and zirconium dioxide implants in cone-beam computed tomography. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2015, 26, 1222–1228.

- Steiger-Ronay, V.; Krcmaric, Z.; Schmidlin, P.R.; Sahrmann, P.; Wiedemeier, D.B.; Benic, G.I. Assessment of peri-implant defects at titanium and zirconium dioxide implants by means of periapical radiographs and cone beam computed tomography: An in-vitro examination. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2018, 29, 1195–1201.

- Benic, G.I.; Thoma, D.S.; Sanz-Martin, I.; Munoz, F.; Hämmerle, C.H.F.; Cantalapiedra, A.; Fischer, J.; Jung, R.E. Guided bone regeneration at zirconia and titanium dental implants: A pilot histological investigation. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2017, 28, 1592–1599.

- Schriber, M.; Yeung, A.W.K.; Suter, V.G.A.; Buser, D.; Leung, Y.Y.; Bornstein, M.M. Cone beam computed tomography artefacts around dental implants with different materials influencing the detection of peri-implant bone defects. Clin. Oral. Implant. Res. 2020, 31, 595–606.

- Saito, M.M.; Onuma, K.; Yamamoto, R.; Yamakoshi, Y. New insights into bioactivity of ceria-stabilized zirconia: Direct bonding to bone-like hydroxyapatite at nanoscale. Mater. Sci. Eng. C Mater. Biol. Appl. 2021, 121, 111665.

- Palmero, P.; Fornabaio, M.; Montanaro, L.; Reveron, H.; Esnouf, C.; Chevalier, J. Towards long lasting zirconia-based composites for dental implants: Part I: Innovative synthesis, microstructural characterization and invitro stability. Biomaterials 2015, 50, 38–46.