Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Sarah Smith Orr, PhD | -- | 2699 | 2023-12-05 03:46:27 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | -3 word(s) | 2696 | 2023-12-05 04:07:26 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Cartwright, C.T.; Harrington, M.; Orr, S.S.; Sutton, T. Women’s Leadership and COVID-19 Pandemic. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52351 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Cartwright CT, Harrington M, Orr SS, Sutton T. Women’s Leadership and COVID-19 Pandemic. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52351. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Cartwright, Chris T., Maura Harrington, Sarah Smith Orr, Tessa Sutton. "Women’s Leadership and COVID-19 Pandemic" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52351 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Cartwright, C.T., Harrington, M., Orr, S.S., & Sutton, T. (2023, December 05). Women’s Leadership and COVID-19 Pandemic. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52351

Cartwright, Chris T., et al. "Women’s Leadership and COVID-19 Pandemic." Encyclopedia. Web. 05 December, 2023.

Copy Citation

International and national crises often highlight behavioral patterns in the labor market that illustrate women’s courage and adaptability in challenging times. The COVID-19 pandemic and resulting changes in the workplace due to social distancing, remote work, and tele-communications protocols showcased women’s power of authenticity and accessibility (interpersonal and personalized experiences) to engage with their constituents effectively.

women’s leadership

crisis leadership

connective leadership

COVID-19 pandemic

1. Background

We are currently experiencing continuous and complex crises impacting every sector worldwide. Researchers explore the many ways in which women leaders were challenged by internal and external forces brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic, and who have pivoted, adapted, and ultimately transformed their leadership practice to best serve their constituencies [1]. The authors acknowledge the persistent pursuit of understanding the distinctions between women and men concerning biologically influenced and socially constructed factors, particularly leadership styles. The participants identify as women, and the writers embrace hybrid neologisms like “gender/sex” [2] and use these terms interchangeably. The interest in studying COVID-19′s impact on women arises from the recognition that the pandemic has highlighted specific challenges and disparities faced by women, emphasizing the need for behavior frameworks to promote fluidity in leadership roles [3].

The authors have conducted a mixed-method analysis of women’s leadership from before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Through our own experiences in our respective fields of work, we were acutely aware that COVID-19 dramatically impacted women in multiple areas of their lives. We specifically wanted to understand better how women’s leadership behavioral profiles have been reinvented during this difficult period. By examining the challenges and experiences of women across sectors through the lens of the Connective Leadership Model [1], we can shed light on the dynamic circumstances they faced during the crisis and how those circumstances influenced their personal and work relationships.

Researchers employed the Meta-Leadership Model for crisis leadership [4] as a basis to better understand how leaders and their organizations can manage a crisis and become stronger, as well as how the dynamics of change can lead to the timely and adaptive modification of leadership behaviors. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on the leadership and work life of women in this study who serve on the front lines in various sectors such as education, health, government, and nonprofit organizations was profound and worthy of study.

Researchers explore how these women mustered the courage to look deeply within themselves, understand the people they serve, and the context in which they serve to determine adaptations that were authentic to who they are and what they bring to their constituents. They chose to be more accessible and accountable to those who needed them and in new ways, previously outside their arenas of work and life. The crisis became a force to better understand that we live in times where “inclusion is critical and connection is inevitable” [1] (p. xiii).

International and national crises often highlight behavioral patterns in the labor market that illustrate women’s courage and adaptability in challenging times. The COVID-19 pandemic and resulting changes in the workplace due to social distancing, remote work, and tele-communications protocols showcased women’s power of authenticity and accessibility (interpersonal and personalized experiences) to engage with their constituents effectively [5][6][7][8][9][10]. Novotney [3] underscores the importance of studying the impact of COVID-19 on women, which catalyzed this research [3][11]. The COVID-19 pandemic brought to light specific challenges and disparities women faced in the workplace [8]. Eagly asserts that women leaders substantially benefit businesses and organizations [12][13][14]. Decades of research reveal that women leaders enhance productivity, foster collaboration, inspire dedication, and promote fairness in the workplace [12][13][14]. Moreover, Eagly’s [12] research has significantly contributed to understanding the challenges women leaders face due to the cultural incongruity between societal expectations of women as communal and leaders as agentic [13][14].

Even with the best of plans for how to routinely address problems, crisis moments will happen, which call for complex problem-solving skills—ones that require the leader to move well beyond their customary sphere of authority and influence—to evaluate impact, determine how to handle a variety of situations effectively, facilitate adaptive responses, and be resilient [3][9][10]. How a leader thinks, behaves, and acts will determine the outcome. A crisis like the COVID-19 pandemic demands that the leader have at their disposal a repertoire of leadership behaviors to engage and deploy resources and connections critical to how the crisis will be defused and managed.

The emotional impact of the pandemic on women and their work is another crucial area to study. Exploring the psychological and emotional toll the pandemic has taken on women in the workplace will help us to understand the long-term effects and the importance of supporting their mental well-being [11]. This emotional toll can include discussing the challenges of balancing personal and professional responsibilities, coping with increased workloads, increased caregiving responsibilities, and managing stress, such as “Zoom fatigue” and burnout [12][13].

Kolga discussed how the change from physical locations to a virtual “online platform” required creating “new ways of working within which the balance of home life and organizational priorities became challenging” [15] (p. 406). Carli was prescient in her sense that rather than a temporary solution, telecommuting “may place an even greater burden on women who have more domestic responsibilities than men and may face more difficulties balancing paid work and family obligations while telecommuting” [14] (p. 647).

Conversely, there are also new levels of balance and resiliency that can only be realized after emerging from a crucible experience, like the COVID-19 pandemic. Our women leaders describe how they transformed themselves and their leadership model despite the extraordinary challenges they faced. “Fulfilling your potential as a leader requires a keen awareness and understanding of how your personal experiences—your decisions, stumbles, and triumphs—got you to where you are now. Each prepares you for the moment when ‘you’re it” [8] (p. 3).

2. Connective Leadership

The genesis of the Connective Leadership Model [1] can be found in Dr. Jean Lipman Blumen’s 1970 Harvard doctoral dissertation, “Educational Aspirations of Married Women.” The major finding suggested that married women met their achievement needs vicariously by identifying with and contributing to the achievements of others. That work continued in a research group led by Lipman-Blumen and Professor Harold J. Leavitt, at Stanford University, in 1972-73. The collaboration produced a more comprehensive model of leadership behavior [16] [17], which acknowledged the differences between male and female preferences. The model has contributed to scholars’ and practitioners’ understanding of the behaviors that leaders use. It has also produced a significant database of over 45,000 leadership profiles spanning the past 50 years. The current study builds upon that foundation by demonstrating that agility and resilience are needed to adapt to new leadership challenges provoked by the COVID-19 pandemic as well as other crises.

A “connective leader” is any individual who uses the appropriate knowledge, skills, and temperament to lead other individuals who differ according to various dimensions (e.g., gender, age, race, nationality, religion, political persuasion, as well as educational and/or occupational background) to work together effectively. Connective leaders understand the complex, broad-based diversity, and technology-enhanced interconnections of their constituents. In a world where interconnectivity has rapidly become global, connective leaders are adept at guiding groups of individuals who differ significantly in myriad ways. The authors of this study felt that the CL model as ideal for research on ways in which women leaders respond to crises, such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

The Connective Leadership/Achieving Styles Model is based on the premise that these leadership styles are learned behaviors which can be used in various combinations. Moreover, training helps individuals to understand which behaviors are most appropriate for any given situation. Both training and practice also enable individuals to improve their skills in using these best-suited styles. The participants in this study were all educated in the CL model prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and had taken the ASI at that time.

To enable groups of diverse individuals to work together effectively, connective leaders call upon a nine-fold repertoire of behavioral strategies (“achieving styles”) to achieve their tasks and accomplish their goals. These achieving styles were studied and described in the 1980s [17] and have been studied across international boundaries, with cultural influences affecting the frequency, strength, and circumstances under which these nine behaviors are implemented [18].

Connective leaders draw upon the entire nine-fold repertoire of achieving styles, in each case depending upon their interpretation of situational cues and their expectation that certain styles will increase their odds of success. By contrast, most other leaders, as well as individuals generally, rely primarily upon their past successes, calling mostly upon a relatively limited subset of previously effective achieving styles.

3. The Achieving Styles Model

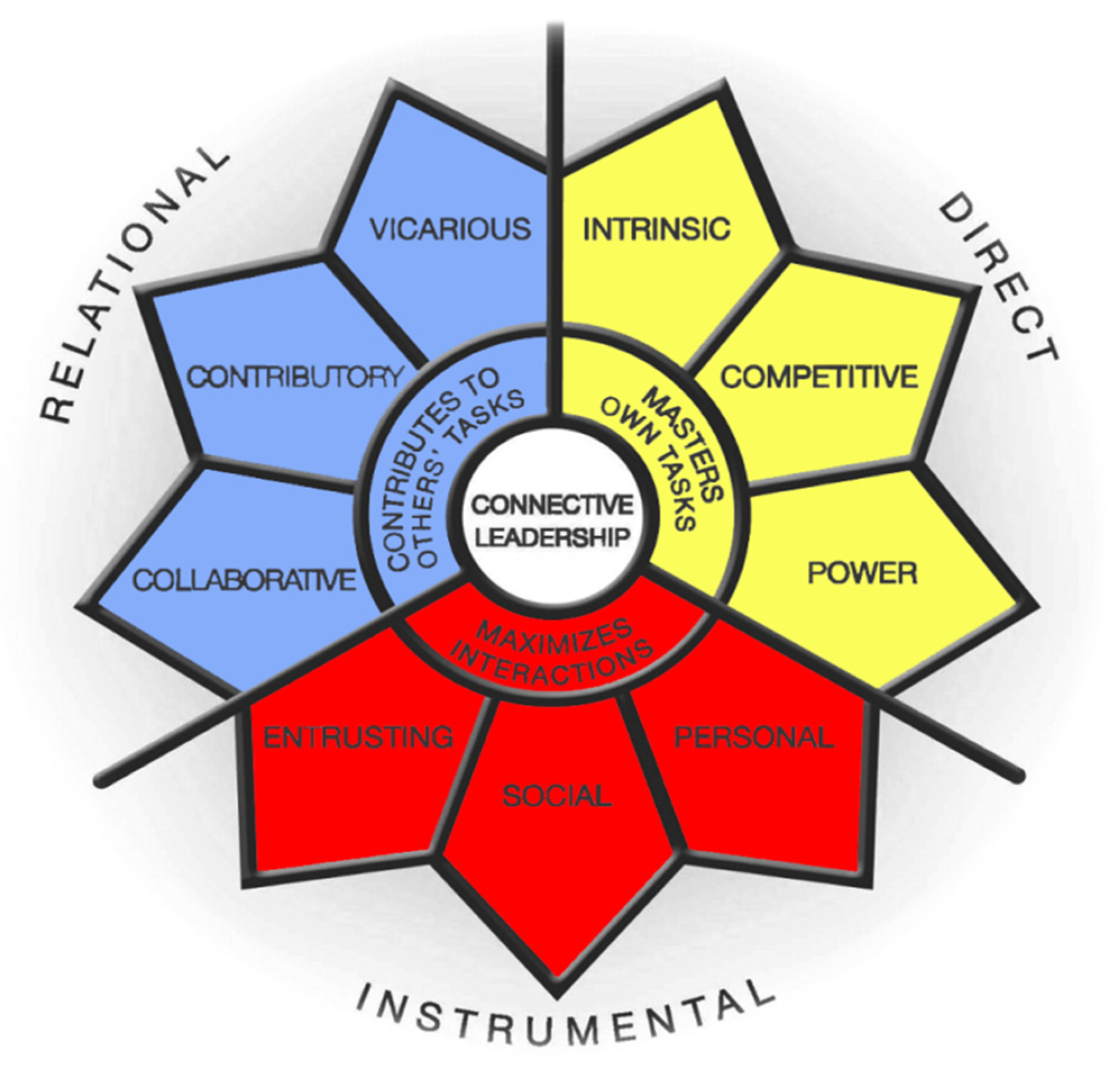

The nine styles are grouped into three sets of domains: direct, instrumental, and relational. Each of these three domains subsumes three styles, resulting in the nine-fold achieving styles repertoire (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Connective Leadership Model.

A brief overview of the domains and dimensions of the Connective Leadership/Achieving Styles Model [1] is offered in Table 1 below.

Table 1. The Connective Leadership Model domains and dimensions.

| DOMAIN/Dimension | Description |

|---|---|

| DIRECT SET | Acts directly on the situation. Controls both the inputs and the outputs of the endeavor. |

| Intrinsic | Self-motivated, incorporates a high standard of excellence for self. |

| Competitive | Derives satisfaction from performing tasks better than others. |

| Power | Prefers to organize, be in control, and manage people, resources, and processes. |

| INSTRUMENTAL SET | Uses self and others as instruments for achievement. Controls the inputs and begins to share the outputs of the endeavor. |

| Personal | Uses their personality, charisma, appearance, intelligence, and background, to attract others and further their goals. |

| Social | Engages other people with relevant training, skills, and/or experience in achieving their goals. |

| Entrusting | Empowers others, even those with no specifically relevant training or experience. |

| RELATIONAL SET | Achieves through relationships. Often sharing both the inputs and the outcomes of the endeavor. |

| Collaborative | Joins others (singularly or as part of a multi-person team) to increase the odds of success. |

| Contributory | Works behind the scenes to help others achieve their goals. |

| Vicarious | Derives a genuine sense of accomplishment for the success of others with whom they identify. |

In sum, these nine achieving styles that constitute the Connective Leadership Model [1] represent the available repertoire used effectively by connective leaders. The styles may be utilized in various combinations. While no individual style is intrinsically better than any other, the purpose of the Achieving Styles Model is to identify leadership strategies appropriate for each specific situation. Moreover, the Connective Leadership Model [1], based upon the nine achieving styles, describes the wide range of behaviors for promoting effectiveness in a world pulled in multiple directions by broad-based diversity and increasing interdependence.

The Connective Leadership Model [1] has wide applicability and flexibility in helping to assess and direct individuals, teams, and organizations to achieve greater and more fulfilling success through its emphasis on diversity and interdependence. This model of leadership is useful in understanding all individuals’ profiles, whether they are in management/leadership positions or not, since it assumes that all individuals accomplish their tasks and achieve their goals through their Achieving Styles Profile.

4. Crisis Leadership

Convinced that the Connective Leadership Model [1] is a highly effective model for leaders during good times and difficult times, especially the COVID-19 pandemic, we identified a crisis leadership model to support our research project. We believed that this additional lens would bring focus to our study of the competencies and skills necessary for leaders as they navigate a crisis.

Sriharan et al. [19] conducted a meta-analysis of 35 crisis leadership and pandemic-related articles drawn from business and medical sources published between 2003 (since SARS) and December 2020. The purpose of this study was to identify the leadership skills and competencies deemed critical during a pandemic. The analysis resulted in the creation of a model that organized crisis leadership into three thematic categories, task, people, and adaptive competencies, while recognizing the relationship with and importance of identifying politics, structure, and culture as contextual enablers and/or barriers [19], p. 482. The three overlapping competency groupings were illustrated and described as follows:

-

Tasks: preparing, planning, communication, and collaboration

-

People: inspiring and influencing, leadership presence, empathy, and awareness

-

Adaptive: decision making, systems thinking/sensemaking, and tacit skills

Sriharan et al.’s [19] meta-analysis reinforced that of Marcus [4]. This earlier work evolved through the founding and research work of the National Preparedness Leadership Initiative (NPLI). The formation of NPLI emerged from a gathering of government leaders and faculty from across Harvard University post-9/11, who met to gain an understanding of and plan for a more effective national response to crises [4] (p. ix). This work has been applied to the Boston Marathon bombings as well as the COVID-19 pandemic [4].

Through their extensive studies, Marcus [4] created a transformational crisis leadership model, Meta-Leadership [14], that consists of three dimensions of leadership (see Table 2) used to describe the various leadership behaviors and means (or tools) in a crisis to “seize the opportunity” as leaders to “find and achieve a complex equilibrium that extends [beyond a single leader or organization] to the broader community” [4] (p. 19). Circling back to the Connective Leadership Model [1] and linking these two models, the leader must understand the complexity and dynamic nature of a situation and modify their leadership style accordingly to see the opportunity and challenges ahead. We believe that this reciprocal relationship validates the Connective Leadership Model [1] as one that can be used in a crisis and beyond; one that embodies the competencies, skills, and behaviors included in other studies, especially compared to the Meta-Leadership Model [4]. Table 2 below compares the two models.

Table 2. Comparison of the Meta-Leadership [4] and Connective Leadership Model [1] and their dimensions.

| Crisis Leadership Meta-Leadership Model Key Elements |

Connective Leadership Model Key Elements |

|---|---|

| The Concept: “Meta-leadership is the idea that in complex systems, a big part of leadership is the capacity to work well with and help steer organizations beyond one’s immediate circle …” [2] (Foreword). “Forging the connectivity enabled them to lead down to reports, lead up to their bosses, lead across to colleagues within their organization, and lead beyond to the people outside their organization’s chain of command … they were together” [4] (p. 20). | The Concept: “Connective Leadership™ is a method that leaders can consciously and systematically use in several ways. The model allows leaders to assess not only their own leadership styles and those of others but also the leadership behaviors most needed in any particular situation and the leadership styles most valued in each organization …” [1] (p. 13). |

| Meta-Leadership’s Dimensions: | Connective Leadership Domains: |

| The Person: Embodying emotional intelligence and a capacity to engage, bonding work with unity of purpose. | Direct Set: Behaviors that confront their own tasks individually and directly. |

| The Situation: Ready for what could come next with little notion of what it might be. | Relational Set: Behaviors that work on group tasks or to help others attain their goals. |

| The Connectivity of Effort: Learning to finesse connections in order to better coordinate and be responsive and adaptive. | Instrumental Set: Behaviors that use personal strengths to attract supporters, create social networks, and entrust others. |

The Connective Leadership Model [1] and the additional lens of the Meta-Leadership Model [4] provide leaders with tools and processes to achieve high levels of authenticity, accountability, accessibility, and adaptability as they lead in a crisis.

Their behaviors “represented a blend of task and relational skills” described as elements of complexity leadership theory and their capacity to “initiate the development of ‘care’ behaviors as part of an androgynous approach to leadership” [15] (pp. 406–407). Through their understanding of the complexities or context of their situation, they were able to facilitate adaptive responses individually and through their teams, allowing for innovation, learning, and growth—”adaptive space”—giving them the opportunity to achieve a variety of system changes [10] (p. 403).

As in Kolga’s 2023 study, our women leaders demonstrated indispensable behaviors during the COVID-19 pandemic for effective communication and relationships that included “nurturing, empathy, cooperation, sensitivity, and warmth, behaviors often attributed to women’s or feminine leadership” [15] (p. 405); behaviors consistent with Eagly’s [14] gender social role theory that “women are communal and men are agentic” [20]. However, our women leaders, as noted above, utilized a “blend” of leadership behaviors embodying a “blended androgynous approach” [15] (p. 409). They are leaders who employed the broadest and most flexible leadership repertoire to meet the complex challenges manifested through a variety of contexts, meeting the demands of leadership in the Connective Era.

References

- Lipman-Blumen, J. Connective Leadership: Managing in a Changing World; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1996.

- Schudson, Z.C.; Beischel, W.J.; van Anders, S.M. Individual variation in gender/sex category definitions. Psychol. Sex. Orientat. Gend. Divers. 2019, 6, 448–460.

- Novotney, A. Women Leaders MAKE Work Better. Here’s the Science Behind How to Promote Them. Available online: https://www.apa.org/topics/women-girls/female-leaders-make-work-better (accessed on 23 March 2023).

- McNulty, E.J.; Marcus, L.; Grimes, J.O.; Henderson, J.; Serino, R. The Meta-Leadership Model for Crisis Leadership. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2021.

- Bardhan, R.; Byrd, T.; Boyd, J. Workforce Management during the Time of COVID-19—Lessons Learned and Future Measures. COVID 2022, 3, 1–27.

- Carli, L. Women, Gender Equality and COVID-19; Emerald Insight; Department of Psychology, Wellesley College: Wellesley, MA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.emerald.com/insight/1754-2413.htm (accessed on 29 July 2023).

- Fulk, A.; Saenz-Escarcega, R.; Kobayashi, H.; Maposa, I.; Agusto, F. Assessing the Impacts of COVID-19 and Social Isolation on Mental Health in the United States of America. COVID 2023, 3, 807–830.

- Luebstorf, S.; Allen, J.A.; Eden, E.; Kramer, W.S.; Reiter-Palmon, R.; Lehmann-Willenbrock, N. Digging into “Zoom Fatigue”: A Qualitative Exploration of Remote Work Challenges and Virtual Meeting Stressors. Merits 2023, 3, 151–166.

- Serafini, A.; Peralta, G.; Martucci, P.; Tagliaferro, A.; Hutchinson, A.; Barbetta, C. COVID-19 Pandemic: Brief Overview of the Consequences on Family Informal Caregiving. COVID 2023, 3, 381–391.

- Ul-Bien, M. Complexity and COVID-19: Leadership and followership in a complex world. J. Manag. Stud. 2021, 58, 1400–1404.

- Carli, L.L.; Eagly, A.H. Women face a labyrinth: An examination of metaphors for women leaders. Gend. Manag. Int. J. 2016, 31, 514–527.

- Eagly, A.H.; Diekman, A.B.; Johannesen-Schmidt, M.C.; Koenig, A.M. Gender Gaps in Sociopolitical Attitudes: A Social Psychological Analysis. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 2004, 87, 796–816.

- Eagly, A.H. Once More: The Rise of Female Leaders. American Psychological Association Research Brief. September 2020. Available online: https://www.apa.org/topics/women-girls/female-leaders (accessed on 21 July 2023).

- Eagly, A.H. Sex Differences in Social Behavior: A Social-Role Interpretation, 1st ed.; Distinguished Lecture Series; A Psychology Press Book; Routledge: London, UK, 1987.

- Kolga, M. Engaging “Care” Behaviors in Support of Employee and Organizational Wellbeing through Complexity Leadership Theory. Merits 2023, 3, 405–415.

- Lipman-Blumen, J.; Leavitt, H.J. Vicarious and Direct Achievement Patterns in Adulthood. Couns. Psychol. 1976, 6, 26–32.

- Lipman-Blumen, J.; Handley-Isaksen, A.; Leavitt, H. Achieving styles in men and women: A model, an instrument, and some findings. In Achievement and Achievement Motives: Psychological and Sociological Approaches; Spence, J., Ed.; Freeman: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1983; pp. 151–204.

- Cartwright, C.; Parvanta, S. Nation-Building: Applying Frames of Analysis a Case Study of Afghanistan. Available online: https://culture-impact.net/nation-building-applying-frames-of-analysis-a-case-study-of-afghanistan/ (accessed on 21 July 2023).

- Sriharan, A.; Hertelendy, A.J.; Banaszak-Holl, J.; Fleig-Palmer, M.M.; Mitchell, C.; Nigam, A.; Gutberg, J.; Rapp, D.J.; Singer, S.J. Public Health and Health Sector Crisis Leadership During Pandemics: A Review of the Medical and Business Literature. Med. Care Res. Rev. 2022, 79, 475–486.

- Alqahtani, T. Barriers to Women’s Leadership. Granite J. Postgrad. Interdiscip. J. 2019, 3, 34–41.

More

Information

Subjects:

Womens Studies

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

871

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

05 Dec 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No