Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Kleftodimos Alexandros | -- | 3002 | 2023-11-27 11:30:33 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 3002 | 2023-11-28 02:13:32 | | | | |

| 3 | Rita Xu | -26 word(s) | 2976 | 2023-12-01 08:55:49 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Kleftodimos, A.; Evagelou, A.; Gkoutzios, S.; Matsiola, M.; Vrigkas, M.; Yannacopoulou, A.; Triantafillidou, A.; Lappas, G. Location-Based Augmented Reality Games in Tourism. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52091 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Kleftodimos A, Evagelou A, Gkoutzios S, Matsiola M, Vrigkas M, Yannacopoulou A, et al. Location-Based Augmented Reality Games in Tourism. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52091. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Kleftodimos, Alexandros, Athanasios Evagelou, Stefanos Gkoutzios, Maria Matsiola, Michalis Vrigkas, Anastasia Yannacopoulou, Amalia Triantafillidou, Georgios Lappas. "Location-Based Augmented Reality Games in Tourism" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52091 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Kleftodimos, A., Evagelou, A., Gkoutzios, S., Matsiola, M., Vrigkas, M., Yannacopoulou, A., Triantafillidou, A., & Lappas, G. (2023, November 27). Location-Based Augmented Reality Games in Tourism. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52091

Kleftodimos, Alexandros, et al. "Location-Based Augmented Reality Games in Tourism." Encyclopedia. Web. 27 November, 2023.

Copy Citation

Location-based augmented reality (AR) games can guide users to visit and explore destinations, get informed, gather points and prizes by accomplishing specific tasks, and meet virtual characters that tell stories.

augmented reality

virtual reality

location-based augmented reality

tourism marketing

1. Introduction

Mixed reality (MR) is being increasingly used in many fields for research and commercial purposes. Amongst these fields is tourism, where augmented reality is employed to enhance the touristic experience and educate visitors through applications that combine the promotion of destinations with education and entertainment. Hobson and William stated in their study [1] that travel itself can be regarded as a secondary reality, where tourists escape temporarily. Tourists often seek to escape into simulated experiences like amusement parks (e.g., Disneyland), totally absorbed into new alternate realities [2][3]. It can be argued that virtual and augmented reality (VR and AR) achieve similar experiences where tourists are immersed in alternate realities [4].

AR and VR applications that combine entertainment and education are being utilized to enhance the tourism experience and promote destinations. These applications can intensify the “presence” of the visitor at a destination [5], and create memorable tourism experiences through game elements such as challenges, rewards, competition, and role-playing [6]. Furthermore, they can increase visitor knowledge and awareness about a destination [7]. By experiencing such applications, the users can gain useful information about a destination, such as its history and geography, the natural environment and its flora and fauna, tangible and intangible cultural heritage [8], transport information, and gastronomy. Consequently, visitor satisfaction is enhanced [9], and that in turn has a positive impact on the destination’s sustainability [10].

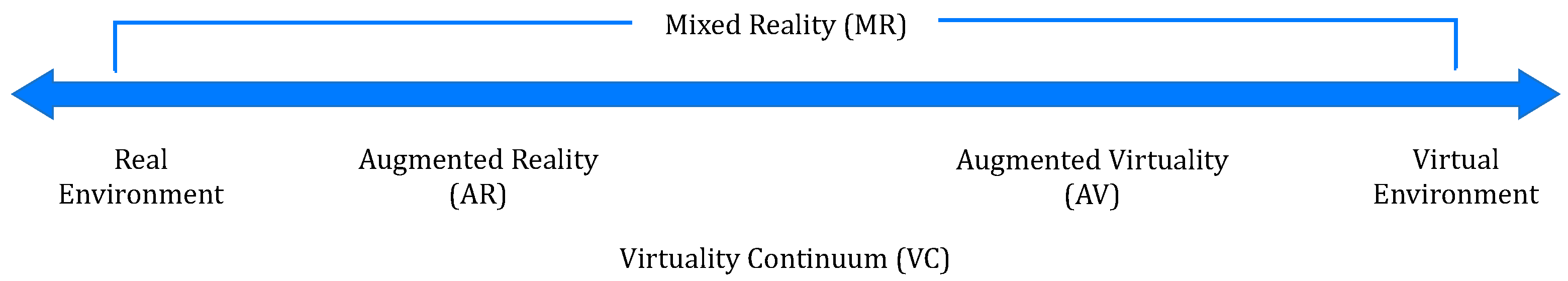

Augmented reality adds a digital information layer to the real world. Augmented reality (AR) applications are situated closer to the left end of the virtuality continuum as can be seen in Figure 1, where real environments lie on the left end and virtual environments on the right end. This space between the two ends contains various levels of mixing between virtual and real-world elements and is known as mixed reality [11].

Figure 1. Representation of the “virtuality continuum”.

Researchers and academics have proposed various definitions for AR [3]. One of the first definitions encountered in the literature was proposed by Azuma in 1997 [12], who defined AR as 3D objects integrated into a 3D real environment in real-time, highlighting three characteristics: (a) a combination of real and virtual, (b) interactive in real-time, and (c) registered in 3D. However, this definition does not encompass all the contemporary variations of augmented reality, and it is more aligned with image-based AR where specific images are needed to register the position of the 3D objects in the real environment [13]. The incorporation of Global Positioning Sensors (GPS) in mobile devices has opened new venues for augmented reality, resulting in a new subset of AR, the location-based or location-aware AR [14]. Location-based AR applications relying on the geolocation capabilities of mobile devices can present to users context-sensitive digital information that is related to their surroundings [3][13][15].

Given that AR, in the years to come after the first definition given by Azuma, evolved to include a variety of applications that blend real and virtual information, a broader and more encompassing definition of AR was needed [16]. By the end of the 2000 decade, many studies presented AR location-based applications that integrate different forms of digital information within real-world settings, such as videos, images, audio, and texts [15][17]. The present study focuses on mobile location-based AR applications and coincides with the broader definition provided by Fitzgerald et al. [16], which defines AR as including “the fusion of any digital information within real-world settings, i.e., being able to augment one’s immediate surroundings with electronic data or information, in a variety of media formats that include not only visual/graphic media but also text, audio, video and haptic overlays”.

Augmented reality can be achieved through wearable and non-wearable devices. Wearable devices include headsets and helmets, such as Microsoft HoloLens, Apple Vision Pro, and Magic Leap and non-wearable devices include mobile devices (smartphones, tablets, etc.) and stationary devices (TVs, PCs, etc.) [18]. Wearable devices are far more expensive than mobile devices, which is why mobile AR applications have played an important role in the significant popularity AR has gained over the last decade.

Quite a few categorizations have been presented throughout the evolution of AR, and one of these is based on the technologies that enable the AR experience (i.e., wearable and non-wearable devices) while another is based on the way that the digital content is triggered. In this categorization, researchers have marker-based, markerless, and location-based augmented reality.

Marker-based AR (or image-based AR) works by scanning a marker that triggers an augmented experience. Markers can be images such as drawings in art museums, street signs, and book pages, as well as real-world objects like statues and bridges. When a marker is viewed through the lens of a mobile device camera or an AR head-mounted display, it will activate digital content. The digital layer of information that superimposes the real world can come in many multimedia forms, such as text, images, videos, sound, 3D models, and 2D and 3D animations.

On the other hand, in markerless AR, digital content is chosen by the users and overlaid on physical surfaces on demand (floor, table, etc.). Finally, location-based AR applications, which can also be considered a type of markerless AR, present digital media to users when they reach specific locations as they move through the physical world. In these applications, GPS sensors constantly track users’ location. Location-based AR has experienced significant growth after the advent of two popular augmented-reality location-based games, namely Pokémon Go and Ingress, created by Niantic in 2014 and 2016, respectively.

Location-based augmented reality games are currently used in several fields, such as entertainment, education, marketing, and tourism. An application can also be used to fulfill more than one purpose. For example, location-based AR games designed for tourism can be used to entertain tourists when they visit a destination, but at the same time, it can also educate them about various aspects of the destination, such as the cultural heritage and history of the place as well as aspects regarding its natural environment (e.g., mountains, rivers, wildlife). Having an experience that combines entertainment and learning about a destination is something that many tourists are looking for today, as acquiring new skills and learning something valuable while traveling is a current trend in tourism, which is especially popular amongst the representatives of Generation Y [19]. Location-based AR games attempt to create a deeper level of engagement between the users and the destination through an experience that combines educational entertainment, storytelling, personalized features, and social interaction [20].

Educational tourism (Edutourism) has been a trend in the global tourism industry for quite some time [21][22]. The main purpose of educational travel is to obtain knowledge and experience on certain topics rather than just enjoying the travel experience. Furthermore, AR and VR through wearable headsets can also promote destinations and educate individuals about these destinations before, during, and after their visit. Overall mixed reality (AR and VR applications) can be a significant asset in tourism marketing and educational tourism [23].

2. Location-Based Augmented Reality Games in Tourism Marketing and Education

There are many initiatives where virtual and augmented reality are used to enhance the destination experience by entertaining and educating the public. In order to spot these research initiatives, the literature was explored by searching Scholar Google and by conducting a bibliometric analysis using VOSViewer 1.6.20 [24] and publications from Scopus. The keywords used were virtual reality and augmented reality in tourism research.

Starting from various initiatives that concern location-based AR games, the authors in [19] analyze how gamified augmented reality experiences impact tourist attractiveness. Their study focuses on the city of Bydgoszcz, which lacks the most popular attributes of sun, sand, and sea, a similar case to the Western Macedonia region in Greece. Their research aimed to analyze the potential of increasing the number of visitors in the city by creating a location-based AR game. The authors also explored whether the game created a memorable experience for the visitors, an experience that would bring them back to the city. The responses received using a survey led to the conclusion that a location-based mobile game using gamification techniques and AR is a memorable experience, and the development of such a game and its introduction on the market would increase the potential of foreign tourism in the destination.

The authors of [7] research through Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) the impact of location-based AR games on the users’ intentions to visit a touristic destination, the role that gained knowledge plays in the experience, and factors driving the adoption of AR games. The study revealed that knowledge gained during gameplay has a statistically significant impact on intentions to visit.

To promote film-induced tourism in Macau, China, the authors of [25] proposed an AR application called “IfilmAR-tour-APP”, which is a location-based AR mobile tour system related to film characters. The application provides film-related information (e.g., film shooting sites and transport to the attractions) as well as emotional attachment with film celebrities. Macau is a place where many film productions take place and this application is intended for tourists that visit film sites.

Location-based AR games are also used extensively in cultural heritage communication and education as this field holds an important role in tourism since many tourists are interested in exploring the history and cultural heritage of the places they visit. Heritage tourism is primarily concerned with the exploration of tangible (material) and intangible (immaterial) remnants of the past [26].

In the recent literature, there are many examples of initiatives that utilize the power of AR to present information regarding the history and cultural heritage of a destination.

For example, in [27], a mobile application called Korat Historical Explorer was developed and evaluated. Korat is the largest province in Thailand with many historical sites including more than 2000 temples. The application has three important AR usage modes consisting of (1) an AR map mode used for looking at the map in the form of print media to display 3D simulations of 10 tourist attractions in Korat, (2) AR landmark mode used for viewing actual objects in their actual locations such as ancient art paintings and mural paintings to view relevant 3D images, and (3) AR direction mode used for leading the user to the important points of the tourist attractions.

Museums and archaeological sites are also entities that employ AR to transmit information in a more engaging way. In these initiatives, when the user gets close to certain locations, the real environment is enriched with digital information, which can be in many multimedia forms such as text and sound, digital stories, animations, 3D reconstructions of monuments, etc.

For example, in [28][29], the researchers explored the enhancement of the visitor experience in outdoor archeological sites and indoor museums with the use of augmented reality technology. These AR applications managed to educate a broad and non-specialized audience with historical and archaeological content in the form of 3D virtual reconstructions. The visitors of these archaeological sites and museums may visualize these reconstructions by looking through the camera lens of their mobile devices at specific targets of the real world.

Jiang et al. [30] examined the efficacy of AR for enhancing the memorability of tourism experiences (MTE) at the heritage site of the Great Wall of China, using a smartphone app, equipped with four interrelated AR heritage tourism experiences. In [31], an AR location-based application that added a layer of 3D models of historical buildings in the real world was created. The 3D models presented how these constructions were in their past state. The authors of [32] developed an AR game called “The buildings speak about our city”, which is a combination of location-based and marker-based augmented reality. The game aims to motivate primary school students to discover the buildings of tobacco warehouses in a city in western Greece, which have historical, architectural, and cultural value, and explore their relationship with the city’s economic and cultural development.

Location-based AR can also be utilized in interior spaces (e.g., museums) where GPS signals are absent with the use of beacons and other tracking devices [29][33].

Furthermore, AR location-based games often harness the power of storytelling to transform an AR tour into a more exciting and engaging experience. Storytelling is known to be a powerful communication method. Storytelling is deeply embedded in human learning, as it provides an organizational structure for new experiences and knowledge [34]. People can mentally organize and memorize information better if it is communicated through stories. Any advancements in media technology that enable people to convey stories in new and innovative ways can have a profound impact. Storytelling is also an effective method of education and instruction. Stories can contain lessons, codified bits of wisdom that are passed on in a memorable and enjoyable form [35].

One of the earliest attempts of AR location-based games that utilize storytelling to entertain and educate tourists is REXplorer [36], an application created for tourists visiting the town of Regensburg, in Germany. REXplorer players encounter virtual characters and, more specifically, spirits of historical figures during gameplay. These virtual characters relate to historic buildings. The AR game aims to make the task of learning history a fun process. The spirits interact with the users, prompting them to go on quests at specific locations within the city center. By performing these quests, the players indirectly explore the historical city center and learn history in an entertaining and engaging way. Of course, there are also plenty of recent examples where AR and storytelling are jointly utilized in tourism to educate the public about a place’s history and cultural heritage [37][38].

Furthermore, as already mentioned, Virtual Reality (VR) is also a technology that is utilized for tourism destination marketing and education, although often in a different way.

Examples of VR applications in tourism can be found in related literature reviews (e.g., [3][39][40]). Yung and Khoo-Lattimore [3] provide a systematic literature review on virtual reality and augmented reality in tourism research, while other reviews focus on either the use of VR or AR in tourism exclusively. For example, Beck et al. provide a state-of-the-art review on virtual reality in tourism [40], Theodoropoulos and Antoniou [39] provide a systematic review of VR games in cultural heritage, while Jingen and Elliot provide a systematic review on AR in tourism research [41]. In the Yung and Khoo-Lattimore review [3], virtual worlds were the most common focus (39% of the studies), and all studies of virtual worlds were based on the Second Life virtual world. The most common focus was studying the destination marketing potential of Second Life. Furthermore, the applications used for the enhancement of the touristic experience were exclusively AR applications. The authors argue that this could be explained with the higher mobile nature of AR when compared to VR, which typically demands the user to be stationary and requires more processing power. Similarly, Moro, Rita, Ramos, and Esmerado argue in their study [42] that although both AR and VR are progressively becoming more common in tourism experiences, VR is commonly designed as the basis of an experience, whilst AR is used to supplement an existing experience. In the study of Roman et al [43], more than 87% of the respondents that took part in a survey believed that VR tourism cannot substitute real-world tourism in the long run. However, the authors argue that VR tourism will be more beneficial for the citizens of developing countries who face difficulties in traveling to developed countries due to economic as well as other reasons (e.g., visas). Furthermore, virtual sightseeing may also constitute an alternative for people who cannot travel due to disabilities or other health conditions.

Moreover, the authors of [41] claim that while virtual reality might be a threat to travel and tourism as a potential substitute, augmented reality allows users to interact with the real environment that could potentially enhance visitors’ experience. On the other hand, one of the findings of the Beck et al. literature review on virtual reality in tourism [40] is that research in this field has most commonly examined the pre-travel phase, using VR as a marketing tool for promotion and communication purposes and therefore end up investigating variables such as travel planning, behavioral intentions, or attitude. Study results suggest that VR, regardless of whether it is non-, semi-, or fully immersive, can positively influence the individual motivation to visit a place. Similarly, several studies that were analyzed in the review conducted by Yung and Khoo-Lattimore [3] found that the engagement and involvement participants felt when interacting with VR led to increased positive feelings toward the destination (e.g., [44][45][46]).

At this point, it has to be said that initiatives that combine both AR and VR are rather rare. For example the idea of “virtual portals” is presented in [47] for outdoor archaeological sites. “Virtual portals” is an idea inspired by many TV series, movies, and video games. Through these portals, the users perform transfers (or jumps) between the real world, AR, and VR reality. The authors explored the possibilities of a mixed reality that contains “shortcuts” (virtual portals) for performing “time travels” to bring the user from the real environment of the present to the virtual environment of the past. The ArkaeVision project [48] is such another example that utilizes both AR and VR but also storytelling and gamification. More specifically, ArkaeVision introduces a game-like exploration of a 3D environment, virtually reconstructed, with elements of digital fiction and engaging storytelling, applied to two case studies: the exploration of the Hera II Temple of Paestum with virtual reality (VR) technology, and the exploration of the slab of the Swimmer Tomb with augmented reality (AR).

As far as education in tourism context is concerned, findings are contradicting amongst studies. In [40], it is stated that VR research in tourism in an educational context is rare, and there is a need for such VR applications. On the other hand, in the systematic review conducted by Yung and Khoo-Lattimore [3], VR and AR research in tourism education is found to be the second most common category.

References

- Perry Hobson, J.S.; Williams, A.P. Virtual reality: A new horizon for the tourism industry. J. Vacat. Mark. 1995, 1, 124–135.

- Cohen, E. Rethinking the sociology of tourism. Ann. Tour. Res. 1979, 6, 18–35.

- Yung, R.; Khoo-Lattimore, C. New realities: A systematic literature review on virtual reality and augmented reality in tourism research. Curr. Issues Tour. 2019, 22, 2056–2081.

- Williams, P.; Hobson, J.P. Virtual reality and tourism: Fact or fantasy? Tour. Manag. 1995, 16, 423–427.

- Champion, E. Critical Gaming: Interactive History and Virtual Heritage; Routledge: London, UK, 2016; ISBN 978-1-317-15739-7.

- Xu, F.; Tian, F.; Buhalis, D.; Weber, J.; Zhang, H. Tourists as Mobile Gamers: Gamification for Tourism Marketing. J. Travel Tour. Mark. 2016, 33, 1124–1142.

- Lacka, E. Assessing the impact of full-fledged location-based augmented reality games on tourism destination visits. Curr. Issues Tour. 2020, 23, 345–357.

- Mortara, M.; Catalano, C.E.; Bellotti, F.; Fiucci, G.; Houry-Panchetti, M.; Petridis, P. Learning cultural heritage by serious games. J. Cult. Herit. 2014, 15, 318–325.

- Prakasa, F.B.P.; Emanuel, A.W.R. Review of Benefit Using Gamification Element for Countryside Tourism. In Proceedings of the 2019 International Conference of Artificial Intelligence and Information Technology (ICAIIT), Yogyakarta, Indonesia, 13–15 March 2019; pp. 196–200.

- Yoo, C.; Kwon, S.; Na, H.; Chang, B. Factors Affecting the Adoption of Gamified Smart Tourism Applications: An Integrative Approach. Sustainability 2017, 9, 2162.

- Milgram, P.; Kishino, F. A Taxonomy of Mixed Reality Visual Displays. IEICE Trans. Inf. Syst. 1994, 77, 1321–1329. Available online: https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/A-Taxonomy-of-Mixed-Reality-Visual-Displays-Milgram-Kishino/f78a31be8874eda176a5244c645289be9f1d4317 (accessed on 20 August 2023).

- Azuma, R.T. A Survey of Augmented Reality. Presence Teleoperators Virtual Environ. 1997, 6, 355–385.

- Cheng, K.-H.; Tsai, C.-C. Affordances of Augmented Reality in Science Learning: Suggestions for Future Research. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 2013, 22, 449–462.

- Martin, S.; Diaz, G.; Sancristobal, E.; Gil, R.; Castro, M.; Peire, J. New technology trends in education: Seven years of forecasts and convergence. Comput. Educ. 2011, 57, 1893–1906.

- Dunleavy, M.; Dede, C. Augmented Reality Teaching and Learning. In Handbook of Research on Educational Communications and Technology; Spector, J.M., Merrill, M.D., Elen, J., Bishop, M.J., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 735–745. ISBN 978-1-4614-3184-8.

- FitzGerald, E.; Ferguson, R.; Adams, A.; Gaved, M.; Mor, Y.; Thomas, R. Augmented Reality and Mobile Learning: The State of the Art. Int. J. Mob. Blended Learn. 2013, 5, 43–58.

- Klopfer, E. Augmented Learning: Research and Design of Mobile Educational Games; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2008; ISBN 978-0-262-11315-1.

- Peddie, J. Types of Augmented Reality. In Augmented Reality; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; pp. 29–46. ISBN 978-3-319-54501-1.

- Enhancing Tourism Potential by Using Gamification Techniques and Augmented Reality in Mobile Games|International Business Information Management Association (IBIMA). Available online: https://ibima.org/accepted-paper/enhancing-tourism-potential-by-using-gamification-techniques-and-augmented-reality-in-mobile-games/ (accessed on 5 August 2023).

- Weber, J. Augmented Reality Gaming: A new Paradigm for Tourist Experience. In Information and Communication Technologies in Tourism 2014: Proceedings of the International Conference in Dublin, Ireland, 21–24 January 2014; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2014; pp. 57–64.

- McGladdery, C.A.; Lubbe, B.A. Rethinking educational tourism: Proposing a new model and future directions. Tour. Rev. 2017, 72, 319–329.

- Ritchie, B. An Introduction to Educational Tourism; Channel View Publications: Clevedon, UK, 2003; ISBN 978-1-873150-50-4.

- Zarzuela, M.M.; Pernas, F.J.D.; Calzón, S.M.; Ortega, D.G.; Rodríguez, M.A. Educational Tourism through a Virtual Reality Platform. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2013, 25, 382–388.

- Leiden University. VOSViewer, Visualizing Scientific landscapes. Available online: https://www.vosviewer.com/ (accessed on 27 October 2023).

- Wu, X.; Lai, I.K.W. The acceptance of augmented reality tour app for promoting film-induced tourism: The effect of celebrity involvement and personal innovativeness. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2021, 12, 454–470.

- Gravari-Barbas, M. Heritage and tourism: From opposition to coproduction. In A Research Agenda for Heritage Tourism; Gravari-Barbas, M., Ed.; Edward Elgar Publishing: Cheltenham, UK, 2020; ISBN 978-1-78990-352-2.

- Phithak, T.; Kamollimsakul, S. Korat Historical Explorer: The Augmented Reality Mobile Application to Promote Historical Tourism in Korat. In Proceedings of the 2020 3rd International Conference on Computers in Management and Business, Tokyo, Japan, 31 January–2 February 2020; pp. 283–289.

- Cisternino, D.; Gatto, C.; De Paolis, L.T. Augmented Reality for the Enhancement of Apulian Archaeological Areas. In Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality, and Computer Graphics; De Paolis, L.T., Bourdot, P., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 10851, pp. 370–382. ISBN 978-3-319-95281-9.

- Tsai, T.-H.; Shen, C.-Y.; Lin, Z.-S.; Liu, H.-R.; Chiou, W.-K. Exploring Location-Based Augmented Reality Experience in Museums. In Universal Access in Human–Computer Interaction. Designing Novel Interactions; Antona, M., Stephanidis, C., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 10278, pp. 199–209. ISBN 978-3-319-58702-8.

- Jiang, S.; Moyle, B.; Yung, R.; Tao, L.; Scott, N. Augmented reality and the enhancement of memorable tourism experiences at heritage sites. Curr. Issues Tour. 2023, 26, 242–257.

- Panou, C.; Ragia, L.; Dimelli, D.; Mania, K. An Architecture for Mobile Outdoors Augmented Reality for Cultural Heritage. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2018, 7, 463.

- Koutromanos, G.; Styliaras, G. “The buildings speak about our city”: A location based augmented reality game. In Proceedings of the 2015 6th International Conference on Information, Intelligence, Systems and Applications (IISA), Corfu, Greece, 6–8 July 2015; pp. 1–6.

- National Slate Museum Application. Available online: https://appadvice.com/app/national-slate-museum-amgueddfa-lechi-cymru/1122132874 (accessed on 25 August 2020).

- Mandler, J.M. Stories, Scripts, and Scenes; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA; Taylor and Francis Group: London, UK, 2014; ISBN 978-1-317-76859-3.

- Azuma, R. Chapter 11: Location-Based Mixed and Augmented Reality Storytelling. In Fundamentals of Wearable Computers and Augmented Reality, 2nd ed.; Barfield, W., Ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2015; pp. 259–276. ISBN 978-1-4822-4350-5.

- Ballagas, R.A.; Kratz, S.G.; Borchers, J.; Yu, E.; Walz, S.P.; Fuhr, C.O.; Hovestadt, L.; Tann, M. REXplorer: A mobile, pervasive spell-casting game for tourists. In Proceedings of the CHI ’07 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 28 April—3 May 2007; pp. 1929–1934.

- Nobrega, R.; Jacob, J.; Coelho, A.; Weber, J.; Ribeiro, J.; Ferreira, S. Mobile location-based augmented reality applications for urban tourism storytelling. In Proceedings of the 2017 24o Encontro Português de Computação Gráfica e Interação (EPCGI), Guimaraes, Portugal, 12–13 October 2017; pp. 1–8.

- Spierling, U.; Winzer, P.; Massarczyk, E. Experiencing the Presence of Historical Stories with Location-Based Augmented Reality. In Interactive Storytelling; Nunes, N., Oakley, I., Nisi, V., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2017; Volume 10690, pp. 49–62. ISBN 978-3-319-71026-6.

- Theodoropoulos, A.; Antoniou, A. VR Games in Cultural Heritage: A Systematic Review of the Emerging Fields of Virtual Reality and Culture Games. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 8476.

- Beck, J.; Rainoldi, M.; Egger, R. Virtual reality in tourism: A state-of-the-art review. Tour. Rev. 2019, 74, 586–612.

- Jingen Liang, L.; Elliot, S. A systematic review of augmented reality tourism research: What is now and what is next? Tour. Hosp. Res. 2021, 21, 15–30.

- Moro, S.; Rita, P.; Ramos, P.; Esmerado, J. Analysing recent augmented and virtual reality developments in tourism. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2019, 10, 571–586.

- Roman, M. Virtual and Space Tourism as New Trends in Travelling at the Time of the COVID-19 Pandemic. Sustainability 2022, 14, 628.

- Huang, Y.; Backman, S.J.; Backman, K.F. Exploring the impacts of involvement and flow experiences in Second Life on people’s travel intentions. J. Hosp. Tour. Technol. 2012, 3, 4–23.

- Huang, Y.C.; Backman, K.F.; Backman, S.J.; Chang, L.L. Exploring the Implications of Virtual Reality Technology in Tourism Marketing: An Integrated Research Framework. Int. J. Tour. Res. 2016, 18, 116–128.

- Kim, J.; Hardin, A. The Impact of Virtual Worlds on Word-of-Mouth: Improving Social Networking and Servicescape in the Hospitality Industry. J. Hosp. Mark. Manag. 2010, 19, 735–753.

- Cisternino, D.; Gatto, C.; D’Errico, G.; De Luca, V.; Barba, M.C.; Paladini, G.I.; De Paolis, L.T. Virtual Portals for a Smart Fruition of Historical and Archaeological Contexts. In Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality, and Computer Graphics; De Paolis, L.T., Bourdot, P., Eds.; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; Volume 11614, pp. 264–273. ISBN 978-3-030-25998-3.

- Bozzelli, G.; Raia, A.; Ricciardi, S.; De Nino, M.; Barile, N.; Perrella, M.; Tramontano, M.; Pagano, A.; Palombini, A. An integrated VR/AR framework for user-centric interactive experience of cultural heritage: The ArkaeVision project. Digit. Appl. Archaeol. Cult. Herit. 2019, 15, e00124.

More

Information

Subjects:

Communication

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

2.5K

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

01 Dec 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No