Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Mayuri Mudgal | -- | 1634 | 2023-11-24 03:13:25 | | | |

| 2 | Rita Xu | Meta information modification | 1634 | 2023-11-24 03:55:39 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Rahi, M.S.; Parekh, J.; Pednekar, P.; Mudgal, M.; Jindal, V.; Gunasekaran, K. Therapeutic Anticoagulation in COVID-19. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52011 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Rahi MS, Parekh J, Pednekar P, Mudgal M, Jindal V, Gunasekaran K. Therapeutic Anticoagulation in COVID-19. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52011. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Rahi, Mandeep Singh, Jay Parekh, Prachi Pednekar, Mayuri Mudgal, Vishal Jindal, Kulothungan Gunasekaran. "Therapeutic Anticoagulation in COVID-19" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52011 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Rahi, M.S., Parekh, J., Pednekar, P., Mudgal, M., Jindal, V., & Gunasekaran, K. (2023, November 24). Therapeutic Anticoagulation in COVID-19. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/52011

Rahi, Mandeep Singh, et al. "Therapeutic Anticoagulation in COVID-19." Encyclopedia. Web. 24 November, 2023.

Copy Citation

Thrombotic complications from COVID-19 are now well known and contribute to significant morbidity and mortality. Different variants confer varying risks of thrombotic complications. Heparin has anti-inflammatory and antiviral effects. Due to its non-anticoagulant effects, escalated-dose anticoagulation, especially therapeutic-dose heparin, has been studied for thromboprophylaxis in hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

COVID-19

thrombosis

coagulopathy

anticoagulation

1. Introduction

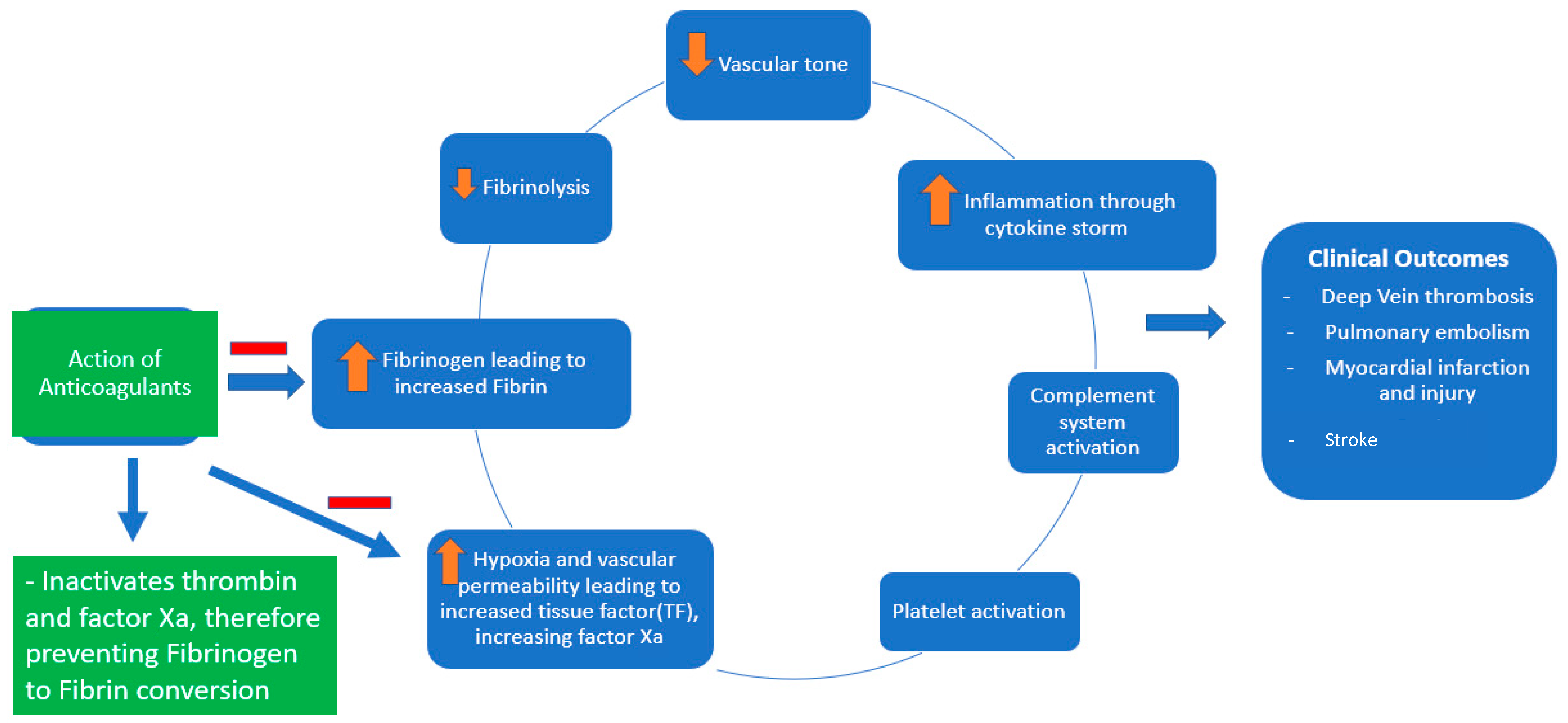

Coagulopathy and thrombosis are now well known complications of COVID-19, contributing to significant morbidity and mortality [1][2]. The pathogenesis of the coagulopathy associated with COVID-19 is complex (Figure 1). It involves macrophage activation, cytokine storm, platelet activation, and endothelial cell activation, eventually activating the intrinsic and extrinsic coagulation pathways [2]. COVID-19 causes DIC, which differs from the typical septic DIC, with less bleeding and elevated fibrinogen levels [1]. Thromboprophylaxis is indispensable in hospitalized patients with COVID-19. There has been significant interest in defining the role of therapeutic-dose anticoagulation, especially with heparin, in patients acutely ill with COVID-19. Although well known for its anticoagulant activity, heparin, either unfractionated heparin (UFH) or low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH), has various other pleiotropic effects [3].

Figure 1. Pathophysiology of COVID-19-associated coagulopathy and the role of anticoagulants (heparin and low-molecular-weight heparin).

Heparin has been shown to exhibit anti-inflammatory and antiviral properties (at a dose of 500–1000 μg/mL heparin in Vero E6 cells) [4][5]. Soluble heparin interacts with the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein and impairs its entry into the host cells [6]. Heparin exerts its anti-inflammatory properties by binding to and inhibiting chemokines, cytokines, and complement, growth, and angiogenic factors. It also prevents endothelial dysfunction and vascular injury by binding to adhesion molecules during inflammation. Heparin reduces vascular leak injury by decreasing thrombin formation [5].

The above-mentioned anti-inflammatory effects (notably, the decreased levels of IL-6, IL-8, and inflammatory biomarkers of COVID-19-CRP and procalcitonin) are also noted with prophylactic doses of LMWH at 40 mg daily [7]. Heparin has been investigated as a therapeutic agent in various inflammatory conditions such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), cystic fibrosis, and sepsis [3][4].

2. Therapeutic-Dose Thromboprophylaxis

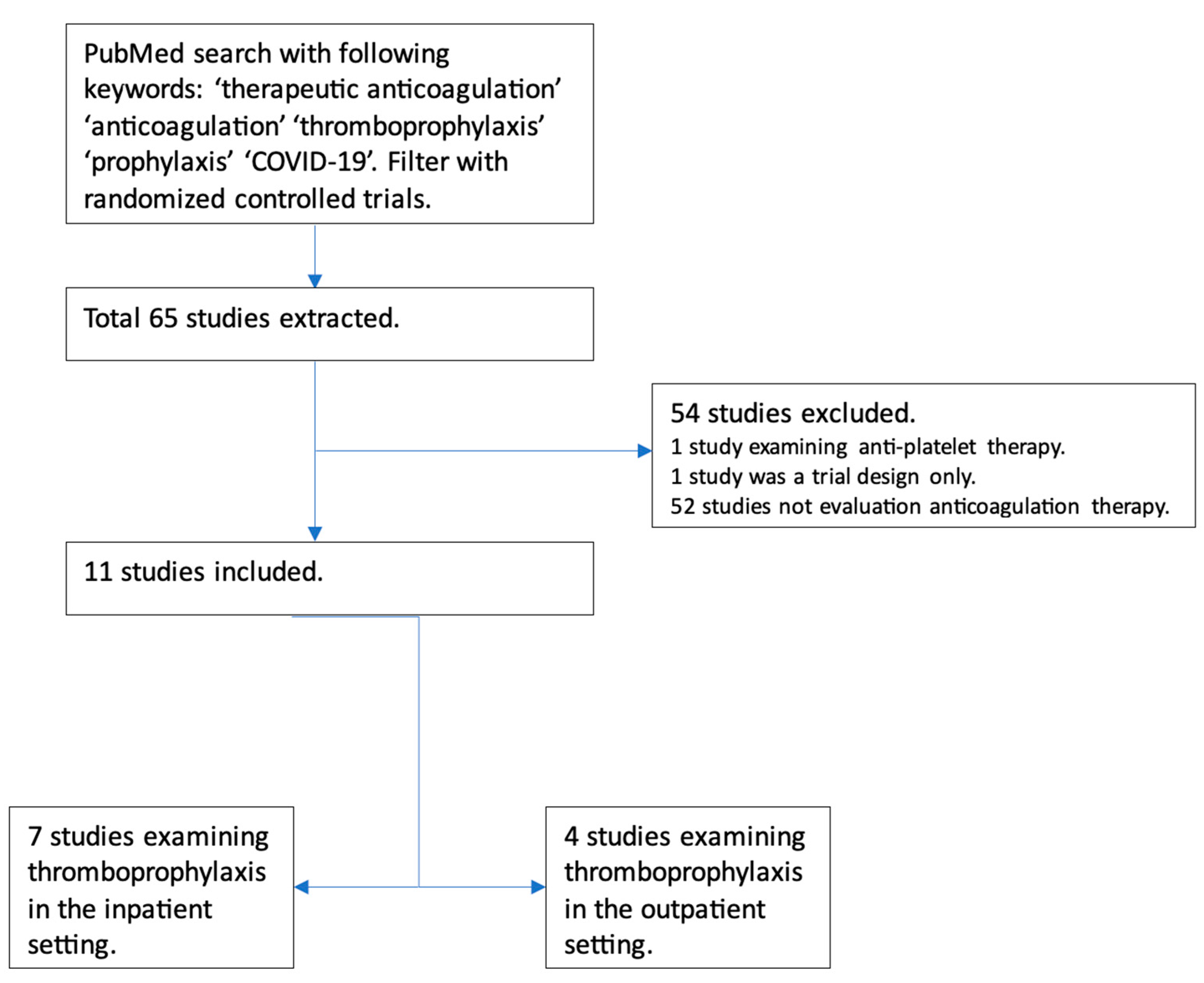

Initial data on the use of anticoagulation in COVID-19 came from China in March 2020, involving 449 patients, out of which 94 received anticoagulation. Still, none of these patients received full-dose anticoagulation [8]. In July 2020, a retrospective analysis was conducted among patients with COVID-19 admitted to a particular health system in New York. This analysis included about 2700 patients with COVID-19. While the exact reason for anticoagulation was unclear among these patients, on multivariate analysis, the study demonstrated survival benefits among the patients who received full-dose anticoagulation compared with those who did not. While it did adjust for prior anticoagulation use before hospitalization for other causes, the study had several limitations. Still, it raised an essential question regarding using full-dose anticoagulation [9]. Researchers identified the clinical trials examining the role of full-dose anticoagulation in patients with COVID-19 infection (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Flowchart depicting trials examining the role of full-dose anticoagulation as prophylaxis in patients with COVID-19 infection.

Seven major randomized controlled trials have examined the role of therapeutic-dose anticoagulation in patients with COVID-19. These included patients with at least moderate COVID-19 infection, elevated D-dimer levels, and low bleeding risk. Significant limitations of these trials were the lack of a standardized definition of disease severity and varied anticoagulation regimens in terms of agents (DOACs and heparin); the duration of anticoagulation, time to randomization, and duration of follow-up varied significantly as well. Furthermore, all had an open-label design, introducing the risk of bias. Standard-of-care thromboprophylaxis practices in the control patients differed; some received intermediate-dose thromboprophylaxis. Despite the limitations, these trials were conducted during the difficult time of an ongoing pandemic and provided invaluable insight into the role of therapeutic-dose anticoagulation, mainly heparin, in hospitalized COVID-19 patients.

In September 2020, a phase 2 trial compared empiric anticoagulation with standard-dose thromboprophylaxis among patients with COVID-19 and ARDS who required mechanical ventilation. Although only ten patients were included in each arm, they found a statistically significant improvement in the blood gas exchange in addition to a decreased need for mechanical ventilation among the therapeutic anticoagulation group [10]. Another propensity-matched analysis of COVID-19 patients showed a mortality benefit among intubated patients but not in non-critically-ill hospitalized patients [11]. The earliest randomized controlled data came from an open-label trial in Brazil that used the therapeutic-dose rivaroxaban or enoxaparin for anticoagulation in COVID-19 admitted patients. The trial included hospitalized patients with elevated D-dimers, with at least a third of the patients in both groups having severe disease. The study did not reveal a statistical difference in the primary composite outcome, including mortality, duration of hospitalization, or period of oxygen needed to day 30. Still, regarding safety outcomes, there was a higher incidence of bleeding events in the therapeutic anticoagulation group [12]. This trial included patients who had symptoms up to 14 days before randomization with a median time of randomization of day 10. Although >80% of patients had moderate disease at baseline, only a quarter had markedly elevated D-dimer (>3 × ULN). A significant difference in this trial was DOAC, which may not have the same non-anticoagulant effects as heparin does.

In August 2021, NEJM published a large multicenter international randomized controlled trial investigating therapeutic-dose anticoagulation in COVID. The investigators stratified patients into moderate vs. severe disease based on ICU requirements and published the results separately. In the moderate disease subgroup, they found therapeutic anticoagulation, compared with prophylactic anticoagulation, was associated with more organ-support-free days, which was statistically significant regardless of the patient’s baseline D-dimer level. There was no significant difference in the risk of major bleeding [13]. The same study reported outcomes of the severe subgroup separately, revealing that therapeutic anticoagulation did not result in a statistically significant difference in organ-support-free survival days [14]. This difference in results was intriguing and there is a possibility that the benefit of anticoagulation may be present only in the initial period of the disease, which would potentially explain the difference in results. There might also be inherent differences among the population developing severe disease, making therapeutic heparin less beneficial. These trials used the new innovative response-adaptative randomization and complex Bayesian analysis. They included clinically meaningful outcomes of organ-support-free days, mortality, and the need for intubation in addition to the incidence of VTE. Some of the limitations of these trials include the risk of confirmation bias given the open-label design; more than 70% of patients were excluded due to the stringent exclusion criteria, which varied among the three trial platforms, diminishing the generalizability of the results.

Around 28% of patients in the control group received higher than standard doses of thromboprophylaxis, and 20% of patients in the experimental group did not receive therapeutic doses of heparin. Only 36% of the patients received remdesivir, 60% received glucocorticoids, and less than 1% received tocilizumab, deviating from the current standard of care with high usage of glucocorticoids and remdesivir early in the disease course [14][15]. The RAPID trial was another adaptive multicenter open-label randomized controlled trial of 465 patients with COVID-19 and elevated D-dimer who were hospitalized in a non-ICU level of care setting. Although the primary composite outcomes of death, invasive or noninvasive mechanical ventilation, or ICU admission did not differ, the all-cause mortality was significantly lower in the therapeutic anticoagulation group (1.8% vs. 7.6%, OR 0.22, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.65; p = 0.006). No increase in major bleeding was noted in the therapeutic anticoagulation group [16].

A recent meta-analysis that included over 5000 patients found that escalated-dose prophylactic anticoagulation (intermediate or therapeutic dose) did not reduce all-cause mortality when compared with standard-dose prophylactic anticoagulation (17.8% vs. 18.6%; risk ratio (RR) 0.96, 95% CI 0.78–1.18). Escalated-dose prophylactic anticoagulation decreased the rates of VTE (2.5% vs. 4.7%; RR 0.55, 95% CI 0.41–0.74) with a number needed to treat (NNT) of 46 but increased the risk of major bleeding (2.4% vs. 1.4%; RR 1.73, 95% CI 1.15–2.60) with a number needed to harm (NNH) of 102. Results did not differ for the subgroups of critically ill and non-critically ill patients. An interesting finding from the meta-analysis was that the median time to randomization was ten days, which one can argue might be late to have benefited from the non-anticoagulation properties of heparin [17]. In contrast, another systematic review included 23 retrospective studies and over 25,000 patients. Therapeutic anticoagulation reduced mortality (RR 0.30, 95% CI 0.15–0.60; I2 58%) but increased the risk of bleeding (RR 2.53, 95% CI 1.60–4.00; I2 58%). The results should be interpreted with caution. All the included studies were observational, and the subgroup analysis had a high degree of heterogeneity [18].

The INSPIRATION trial examined the role of intermediate-dose thromboprophylaxis compared with a standard dose in 562 critically ill patients with COVID-19. There was no difference in the composite outcome of venous or arterial thrombosis, treatment with ECMO, or 30-day mortality. The intermediate-dosing group had statistically significant thrombocytopenia but without increased risk of major bleeding [19]. Following this, Perepu et al. analyzed 176 patients with COVID-19 who were critically ill and received either intermediate-dose or standard-dose thromboprophylaxis. There were no differences in all-cause mortality, thrombotic complications, or major bleeding events [20]. In a recent trial, rivaroxaban was superior to prophylactic enoxaparin in preventing thrombotic events with less bleeding in patients with mild to moderate COVID-19 infection. This study included only 230 patients, limiting the generalizability [21].

The role of anticoagulation has also been studied in outpatients, given the concern for thrombosis in this subgroup of patients. The ACTIV 4B trial compared antithrombotics and anticoagulants in symptomatic COVID-19 patients in the outpatient setting. The study included four groups: low-dose aspirin, 2.5 mg apixaban, 5 mg apixaban, and placebo. All groups had similar primary outcomes: a composite of all-cause mortality, symptomatic venous or arterial thromboembolism, and hospitalization from pulmonary and cardiovascular events, including myocardial infarction and stroke. There were no major bleeding events [22]. In another multicenter trial from Brazil, rivaroxaban at discharge in patients at high risk for venous thromboembolism reduced the risk of venous or arterial thromboembolic events and cardiovascular death on day 35 [23]. The ETHIC trial, examining the role of LMWH in unvaccinated outpatients with COVID-19, was stopped early due to slow enrollment and low event rates. It suggested no benefit of using LMWH [24]. Another prospective trial examining the role of post-discharge thromboprophylaxis with apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily was inconclusive, as the study was stopped early due to a low event rate [25].

References

- Asakura, H.; Ogawa, H. COVID-19-associated coagulopathy and disseminated intravascular coagulation. Int. J. Hematol. 2021, 113, 45–57.

- Rahi, M.S.; Jindal, V.; Reyes, S.-P.; Gunasekaran, K.; Gupta, R.; Jaiyesimi, I. Hematologic disorders associated with COVID-19: A review. Ann. Hematol. 2021, 100, 309–320.

- Tritschler, T.; Le Gal, G.; Brosnahan, S.; Carrier, M. POINT: Should Therapeutic Heparin Be Administered to Acutely Ill Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19? Yes. Chest 2022, 161, 1446–1448.

- Conzelmann, C.; Müller, J.A.; Perkhofer, L.; Sparrer, K.M.; Zelikin, A.N.; Münch, J.; Kleger, A. Inhaled and systemic heparin as a repurposed direct antiviral drug for prevention and treatment of COVID-19. Clin. Med. Lond 2020, 20, e218–e221.

- Cassinelli, G.; Naggi, A. Old and new applications of non-anticoagulant heparin. Int. J. Cardiol. 2016, 212 (Suppl. 1), S14–S21.

- Kim, S.Y.; Jin, W.; Sood, A.; Montgomery, D.W.; Grant, O.C.; Fuster, M.M.; Fu, L.; Dordick, J.S.; Woods, R.J.; Zhang, F.; et al. Characterization of heparin and severe acute respiratory syndrome-related coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) spike glycoprotein binding interactions. Antivir. Res. 2020, 181, 104873.

- Saithong, S.; Saisorn, W.; Tovichayathamrong, P.; Filbertine, G.; Torvorapanit, P.; Wright, H.L.; Edwards, S.W.; Leelahavanichkul, A.; Hirankarn, N.; Chiewchengchol, D. Anti-Inflammatory Effects and Decreased Formation of Neutrophil Extracellular Traps by Enoxaparin in COVID-19 Patients. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 4805.

- Tang, N.; Bai, H.; Chen, X.; Gong, J.; Li, D.; Sun, Z. Anticoagulant treatment is associated with decreased mortality in severe coronavirus disease 2019 patients with coagulopathy. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2020, 18, 1094–1099.

- Paranjpe, I.; Fuster, V.; Lala, A.; Russak, A.J.; Glicksberg, B.S.; Levin, M.A.; Charney, A.W.; Narula, J.; Fayad, Z.A.; Bagiella, E.; et al. Association of Treatment Dose Anticoagulation with In-Hospital Survival Among Hospitalized Patients With COVID-19. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 122–124.

- Lemos, A.C.B.; do Espírito Santo, D.A.; Salvetti, M.C.; Gilio, R.N.; Agra, L.B.; Pazin-Filho, A.; Miranda, C.H. Therapeutic versus prophylactic anticoagulation for severe COVID-19: A randomized phase II clinical trial (HESACOVID). Thromb. Res. 2020, 196, 359–366.

- Yu, B.; Gutierrez, V.P.; Carlos, A.; Hoge, G.; Pillai, A.; Kelly, J.D.; Menon, V. Empiric use of anticoagulation in hospitalized patients with COVID-19: A propensity score-matched study of risks and benefits. Biomark. Res. 2021, 9, 29.

- Lopes, R.D.; de Barros E Silva, P.G.M.; Furtado, R.H.M.; Macedo, A.V.S.; Bronhara, B.; Damiani, L.P.; Barbosa, L.M.; de Aveiro Morata, J.; Ramacciotti, E.; de Aquino Martins, P.; et al. Therapeutic versus prophylactic anticoagulation for patients admitted to hospital with COVID-19 and elevated D-dimer concentration (ACTION): An open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 2021, 397, 2253–2263.

- Lawler, P.R.; Goligher, E.C.; Berger, J.S.; Neal, M.D.; McVerry, B.J.; Nicolau, J.C.; Gong, M.N.; Carrier, M.; Rosenson, R.S.; Reynolds, H.R.; et al. Therapeutic Anticoagulation with Heparin in Noncritically Ill Patients with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 790–802.

- Goligher, E.C.; Bradbury, C.A.; McVerry, B.J.; Lawler, P.R.; Berger, J.S.; Gong, M.N.; Carrier, M.; Reynolds, H.R.; Kumar, A.; Turgeon, A.F.; et al. Therapeutic Anticoagulation with Heparin in Critically Ill Patients with COVID-19. N. Engl. J. Med. 2021, 385, 777–789.

- Jimenez, D.; Rali, P.; Doerschug, K. COUNTERPOINT: Should Therapeutic Heparin Be Administered to Acutely Ill Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19? No. Chest 2022, 161, 1448–1451.

- Sholzberg, M.; Tang, G.H.; Rahhal, H.; AlHamzah, M.; Kreuziger, L.B.; Áinle, F.N.; Alomran, F.; Alayed, K.; Alsheef, M.; AlSumait, F.; et al. Effectiveness of therapeutic heparin versus prophylactic heparin on death, mechanical ventilation, or intensive care unit admission in moderately ill patients with COVID-19 admitted to hospital: RAPID randomised clinical trial. Bmj 2021, 375, n2400.

- Ortega-Paz, L.; Galli, M.; Capodanno, D.; Franchi, F.; Rollini, F.; Bikdeli, B.; Mehran, R.; Montalescot, G.; Gibson, C.M.; Lopes, R.D.; et al. Safety and efficacy of different prophylactic anticoagulation dosing regimens in critically and non-critically ill patients with COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Pharmacother. 2021, 8, 677–686.

- Parisi, R.; Costanzo, S.; Di Castelnuovo, A.; de Gaetano, G.; Donati, M.B.; Iacoviello, L. Different Anticoagulant Regimens, Mortality, and Bleeding in Hospitalized Patients with COVID-19: A Systematic Review and an Updated Meta-Analysis. Semin. Thromb. Hemost. 2021, 47, 372–391.

- Sadeghipour, P.; Talasaz, A.H.; Rashidi, F.; Sharif-Kashani, B.; Beigmohammadi, M.T.; Farrokhpour, M.; Sezavar, S.H.; Payandemehr, P.; Dabbagh, A.; Moghadam, K.G.; et al. Effect of Intermediate-Dose vs Standard-Dose Prophylactic Anticoagulation on Thrombotic Events, Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Treatment, or Mortality among Patients with COVID-19 Admitted to the Intensive Care Unit: The INSPIRATION Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021, 325, 1620–1630.

- Perepu, U.S.; Chambers, I.; Wahab, A.; Ten Eyck, P.; Wu, C.; Dayal, S.; Sutamtewagul, G.; Bailey, S.R.; Rosenstein, L.J.; Lentz, S.R. Standard prophylactic versus intermediate dose enoxaparin in adults with severe COVID-19: A multi-center, open-label, randomized controlled trial. J. Thromb. Haemost. 2021, 19, 2225–2234.

- Kumar, D.; Kaimaparambil, V.; Chandralekha, S.; Lalchandani, J. Oral Rivaroxaban in the Prophylaxis of COVID-19 Induced Coagulopathy. J. Assoc. Physicians India 2022, 70, 11–12.

- Connors, J.M.; Brooks, M.M.; Sciurba, F.C.; Krishnan, J.A.; Bledsoe, J.R.; Kindzelski, A.; Baucom, A.L.; Kirwan, B.A.; Eng, H.; Martin, D.; et al. Effect of Antithrombotic Therapy on Clinical Outcomes in Outpatients with Clinically Stable Symptomatic COVID-19: The ACTIV-4B Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 2021, 326, 1703–1712.

- Ramacciotti, E.; Barile Agati, L.; Calderaro, D.; Aguiar, V.C.R.; Spyropoulos, A.C.; de Oliveira, C.C.C.; Lins Dos Santos, J.; Volpiani, G.G.; Sobreira, M.L.; Joviliano, E.E.; et al. Rivaroxaban versus no anticoagulation for post-discharge thromboprophylaxis after hospitalisation for COVID-19 (MICHELLE): An open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet 2022, 399, 50–59.

- Cools, F.; Virdone, S.; Sawhney, J.; Lopes, R.D.; Jacobson, B.; Arcelus, J.I.; Hobbs, F.D.R.; Gibbs, H.; Himmelreich, J.C.L.; MacCallum, P.; et al. Thromboprophylactic low-molecular-weight heparin versus standard of care in unvaccinated, at-risk outpatients with COVID-19 (ETHIC): An open-label, multicentre, randomised, controlled, phase 3b trial. Lancet Haematol. 2022, 9, e594–e604.

- Wang, T.Y.; Wahed, A.S.; Morris, A.; Kreuziger, L.B.; Quigley, J.G.; Lamas, G.A.; Weissman, A.J.; Lopez-Sendon, J.; Knudson, M.M.; Siegal, D.M.; et al. Effect of Thromboprophylaxis on Clinical Outcomes after COVID-19 Hospitalization. Ann. Intern. Med. 2023, 176, 515–523.

More

Information

Subjects:

Hematology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

689

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

24 Nov 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No