Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AHOUD JAZZAR | -- | 1991 | 2023-11-18 11:07:52 | | | |

| 2 | Wendy Huang | Meta information modification | 1991 | 2023-11-20 09:35:35 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Aldehlawi, H.; Jazzar, A. Effect of Licorice on Oral Health. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/51773 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Aldehlawi H, Jazzar A. Effect of Licorice on Oral Health. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/51773. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Aldehlawi, Hebah, Ahoud Jazzar. "Effect of Licorice on Oral Health" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/51773 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Aldehlawi, H., & Jazzar, A. (2023, November 18). Effect of Licorice on Oral Health. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/51773

Aldehlawi, Hebah and Ahoud Jazzar. "Effect of Licorice on Oral Health." Encyclopedia. Web. 18 November, 2023.

Copy Citation

Licorice (Radix glycyrrhizae) is a plant root extract widely used in various applications, including cosmetics, food supplements, and traditional medicine. It has a long history of medicinal use in different cultures due to its diverse pharmacological properties. Licorice has traditionally been used for treating gastrointestinal problems, respiratory infections, cough, bronchitis, arthritis, and skin conditions. The potential therapeutic benefits of licorice for oral health have gained significant interest.

licorice

dental caries

periodontal disease

aphthous ulcer

xerostomia

oral lichen planus

halitosis

oral mucositis

1. Introduction

Licorice root (Radix glycyrrhizae) is obtained from the roots of Glycyrrhiza glabra L. (G. glabra), a small, flowering, bushy perennial plant of the family Fabaceae that is native to Western Asia, North Africa, and Southern Europe [1]. It is also sourced from Glycyrrhiza uralensis Fisch, referred to as Chinese licorice, which is a perennial herb of the family Fabaceae native to Asia [2]. The roots of these plants are harvested, dried, and then processed to produce licorice root extract, which is used in a variety of applications, including cosmetics, foods, tobacco, and traditional and herbal medicine [3]. The importance of medicinal plants is acknowledged on a global scale. They play a crucial role in the lives of rural residents, particularly in the remote parts of nations with few modern health services. Over 70,000 plant species are known to be used for therapeutic reasons [4]. Many studies have investigated the preservation of traditional knowledge and aimed to accelerate the development of new pharmaceuticals since the biodiversity of natural plants in various places offers quick, affordable, and ample alternative supplies for local health care [5]. Cosmetic products utilise licorice root extract due to its anti-inflammatory and skin-soothing properties [6]. In traditional Chinese medicine, “nine out of ten formulae contain licorice”; it is considered one of the essential herbal medications [7]. Licorice root has traditionally been used in herbal medicine to treat gastrointestinal problems [8], such as gastritis and peptic ulcers [9]. It is still commonly recommended for respiratory infections, coughs, bronchitis [10], and arthritis. Additionally, it is applied topically to manage skin conditions like eczema and psoriasis, as well as enhance wound healing [11][12][13]. Recently, the use of licorice in the treatment and management of oral diseases has been recognised [14]. Oral health is an important aspect of overall health and wellbeing. Maintaining good oral health involves maintaining healthy teeth, gums, and oral tissues, which can contribute to preventing oral diseases. Common oro-dental conditions treated or managed by licorice include dental caries, periodontitis, halitosis, candidiasis, and recurrent aphthous ulcers.

Because of its many biological advantages, such as its anti-inflammatory, antioxidative, and antibacterial activities, licorice has been extensively researched [15]. This is because antimicrobial drug resistance has necessitated the creation of alternative medications. Numerous clinical trials and animal studies have been carried out globally to assess the potential of licorice and its bioactive components, such as glabridin, licoricidin, licorisoflavan A, licochalcone A, and glycyrrhizin, in the prevention and treatment of several oral diseases such as dental caries, periodontal diseases, candidiasis, aphthous ulcers, and even severe conditions such as oral cancer [16].

2. Dental Caries

Studies carried out in recent decades have confirmed the anticariogenic role of natural compounds extracted from licorice, specifically glycyrrhizin and triterpenoid saponin glycosides in G. glabra. The first property investigated was the antiadherent property of glycyrrhizin that inhibits the glucosyltransferase activity of Streptococcus mutans, which is required for biofilm formation [17]. Several studies have investigated the surface coating effect of glycyrrhizin, but conflicting results have been reported [18][19][20]. Other studies have used licorice as an ingredient in oral hygiene products [21], but additional clinical trials are required to confirm its potential effectiveness in controlling dental caries.

3. Periodontal Disease

The use of herbal formulations is seen as an attractive alternative to conventional antibiotics. Thus, the use of licorice in periodontal therapy has been studied. Licorice extract demonstrated potent anti-inflammatory effects by inhibiting inflammatory cytokines [22][23]. A recent study has shown that licorice and chlorhexidine mouthwash both prevent plaque buildup and gingival irritation [24]. Since the chemical ingredients of mouthwashes commonly available on the market have many side effects with prolonged usage, herbal mouthwash has been a better alternative for self-care treatment. Another study showed that patients who used G. glabra gum paint at a 10% concentration experienced a considerable reduction in gingival bleeding, probing pocket depth, and attachment loss [25]. A comprehensive review has documented a list of studies investigating the therapeutic potential of licorice extract in periodontal therapy [26]. As they have no side effects, they can be used for extended periods of time; therefore, they are an effective substitute for chemicals in the prevention and treatment of periodontal disease. On the other hand, limited studies have investigated the effect of licorice on gingivitis. Aqueous extracts of raw polysaccharides from G. glabra have been shown to have strong antiadhesive effects against Porphyromonas gingivalis (P. gingivalis) [27].

4. Oral Candidiasis

Several animal studies have been conducted investigating the antifungal effect of licorice compounds. In one study, glycyrrhizin treatment increased mice’s resistance to C. albicans infection [28]. The antifungal effects of organic solvent extracts of G. glabra against C. albicans have previously been reported [29]. In an in vitro investigation, it was observed that glabridin exhibits a significant effect against amphotericin-B-resistant isolates of C. albicans [30]. Another study demonstrated that by influencing the CD4+ Th1 immune response, the licorice flavonoid liquiritigenin exhibits an immunomodulatory effect and can protect mice from disseminated candidiasis [31]. Investigations have also been conducted on how licorice ingredients affected the virulence characteristics of C. albicans; it was found that glabridin and licochalcone A both blocked the yeast–hyphal transition. Additionally, they claimed that nystatin and each of these substances could work together to combat C. albicans [32].

5. Recurrent Aphthous Ulcer

Various studies have been published on the effectiveness of licorice in reducing aphthous ulcers’ healing time and controlling pain. Using a mouthwash with a deglycyrrhizinated licorice extract for two weeks seemed to reduce discomfort and hasten the healing of aphthous ulcers [33]. The efficacy of licorice bioadhesive hydrogel patches to promote healing and relieve pain suggested that mechanical mucosal protection alone was crucial in lowering pain and encouraging healing. This conclusion was reached as licorice-containing biopatches are nearly as effective as the control patches without licorice. Due to the small sample size and the use of a low licorice concentration (1%) in the experiment, this study was not conclusive [34]. On the other hand, using a dissolving oral patch containing licorice extract for up to 8 days reduced ulcer size and pain compared to using a placebo patch in a randomised, double-blind clinical trial [35]. It was also shown that over-the-counter patches containing licorice extract modify the course of aphthous ulcers by shortening the time and reducing the size and discomfort of lesions, which speeds up healing [36].

6. Herpes Simplex Virus Infection

Due to its antiviral activity, the potential use of licorice in reducing the severity and duration of herpes simplex virus (HSV) infections has been investigated. It has been demonstrated that by creating an environment that was resistant to HSV1 replication, glycyrrhizin possessed its anti-HSV1 action [37]. A clinical trial has demonstrated that the topical application of the GA derivative (Carbenoxolone) in the management of herpetic gingivostomatitis and recurrent herpes labialis was very effective in reducing the pain and healing time [38]. Another study has tested glycyrrhizin gel on patients who suffer from herpes on their lips and nose; this study also showed a reduction in pain and healing time as in the previous study [39]. In addition, a more recent study evaluated the design and formulation of a gel containing extracts of five herbs, including licorice, and concluded that it reduced the recovery time and that the anti-inflammatory, local analgesic, and wound-healing properties are attributed to licorice and rosemary [40]. Furthermore, a successful resolution upon using topical botanical gel treatment for recurrent oro-facial herpes simplex was reported in a single case [41].

7. Xerostomia

The effect of licorice on xerostomia studied in haemodialysis patients in a randomised controlled trial (RCT) has shown that only the licorice mouthwash offered subjective xerostomia alleviation. Clean water and licorice-containing mouthwash have both improved the objective measurement of salivary flow rate [42]. This implies that using licorice mouthwash may help haemodialysis patients who have dry mouth. It has been suggested that since licorice has a sweet flavour and acts as a gustatory stimulant, it may stimulate saliva production and improve the symptom of xerostomia, which was noted among haemodialysis patients [43].

8. Oral Lichen Planus (OLP)

A Japanese study has shown that patients with OLP who tested positive for HCV have shown clinical improvement in OLP after the intravenous administration of glycyrrhizin [44][45]. Intravenous glycyrrhizin therapy for healthcare patients is well established; it is unclear if this treatment has its effect directly on lichen planus lesions or the underlying viral hepatitis. It would be much easier to understand this mechanism if the topical application of licorice extract was utilized. However, it has been demonstrated that licorice patches are effective at reducing pain but not at improving clinical symptoms compared to topical steroid therapy [46]. Meanwhile, a reduction in pain, erythema, burning sensation, and functional disturbance after using a prepared mouthwash formulation of aloe vera, licorice, and sesame oil in patients with OLP has been reported [47].

9. Halitosis

It has been shown that licorice extract and the two isolates, licoricidin and licorisoflavan, can serve as natural components that have the ability to decrease the production of bacterial volatile sulphur compounds by P. gingivalis, Prevotella intermedia, and Solobacterium moorei and thus potentially manage halitosis [48]. Compared to conventional mouthwashes, the ability of Manuka honey and licorice root extract to reduce P. gingivalis bacterial growth has been studied. There are some safety concerns about the available commercial mouthwashes, necessitating the search for more natural ingredients [49].

10. Oral Mucositis

In cancer patients, particularly those with head and neck cancer, G. glabra extract can be used effectively in the prevention and treatment of oral mucositis following radiation and chemotherapy. It is advantageous in two ways: first, there are no interruptions of their chemotherapy or radiation; second, their food intake is not significantly impacted, allowing patients to maintain their nutritional state [50]. In an RCT, it has been reported that aqueous glycyrrhiza extract can be useful for reducing the severity of oral mucositis in patients with head and neck cancer receiving radiotherapy compared to a placebo [51]. Another RCT found that both triamcinolone and licorice mucoadhesive films are effective in the management of oral mucositis during radiotherapy [52]. A clinically significant decrease in mucositis was also observed when lyophilised licorice extract (5% w/v) was used as a mouthwash before and right after each session of radiation therapy [53].

11. Oral Squamous Cell Carcinoma (OSCC)

Isoliquiritigenin (ISL) is a flavonoid with a significant therapeutic potential for treating adenoid cystic carcinoma and the potential to be used as a cancer chemotherapeutic agent [54]. In another study, licochalcone A was reported to induce the apoptotic cell death of OSCC cells; thus, it can be used as a chemotherapeutic agent [55]. Further cell line studies have reported similar findings [56][57][58]. In addition, it was found that human oral cancer cell proliferation was inhibited by a polysaccharide found in Glycyrrhiza inflata by causing apoptosis via the mitochondrial pathway [59].

12. Oral Submucous Fibrosis (OSF)

Licorice was suggested as a treatment for OSF because it demonstrated antifibrotic effectiveness in human fibroblast cell lines [60].

13. Implications in Endodontics

The usefulness of licorice as a root canal irrigant and medication has only been studied in a small number of in vitro investigations. In one of these studies, it was demonstrated that, compared to Ca(OH)2 alone, licorice extract had a much greater inhibitory impact against Enterococcus faecalis (E. faecalis) [61]. Furthermore, another study has shown that with zinc oxide eugenol-based sealer, the highest zones of bacterial growth inhibition were seen when G. glabra was added [62]. A recent study has found that propolis (a resin-like material made by bees from the buds of poplar and cone-bearing trees) is more effective against E. faecalis compared to G. glabra and Ca(OH)2, despite the reduction in the number of colonies in all types of irrigation [63].

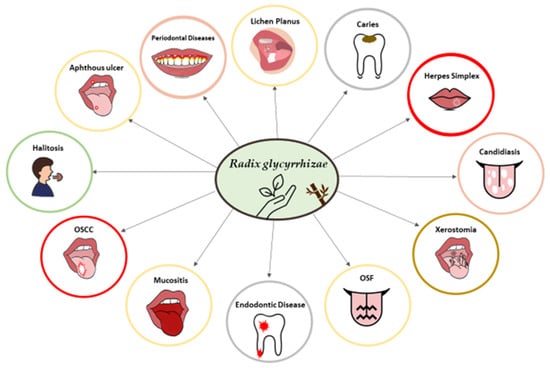

An illustration of the effects of licorice on oral health is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Effect of licorice (Radix glycyrrhizae) on oral health.

References

- Cântar, I.-C.; Dincă, L. TTrifolium genus species present in “alexandru beldie” herbarium from “marin drăcea” national institute for research and development in forestry. Ann. West. Univ. Timisoara. Ser. Biol. 2018, 21, 123.

- Parvaiz, M.; Hussain, K.; Khalid, S.; Hussnain, N.; Iram, N.; Hussain, Z.; Ali, M.A. A review: Medicinal importance of Glycyrrhiza glabra L.(Fabaceae family). Glob. J. Pharmacol. 2014, 8, 8–13.

- Pastorino, G.; Cornara, L.; Soares, S.; Rodrigues, F.; Oliveira, M. Liquorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra): A phytochemical and pharmacological review. Phytother. Res. 2018, 32, 2323–2339.

- Akbulut, S.; Karaköse, M.; Şen, G. Medicinal plants used in folk medicine of akcaabat district (Turkey). Fresenius Environ. Bull. 2022, 31, 7160–7176.

- Karaköse, M. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants in Güce district, north-eastern Turkey. Plant Divers. 2022, 44, 577–597.

- Yang, R.; Yuan, B.C.; Ma, Y.S.; Zhou, S.; Liu, Y. The anti-inflammatory activity of licorice, a widely used Chinese herb. Pharm. Biol. 2017, 55, 5–18.

- Jiang, M.; Zhao, S.; Yang, S.; Lin, X.; He, X.; Wei, X.; Song, Q.; Li, R.; Fu, C.; Zhang, J.; et al. An “essential herbal medicine”-licorice: A review of phytochemicals and its effects in combination preparations. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2020, 249, 112439.

- Bethapudi, B.; Murugan, S.K.; Nithyanantham, M.; Singh, V.K.; Agarwal, A.; Mundkinajeddu, D. Gut health benefits of licorice and its flavonoids as dietary supplements. In Nutrition and Functional Foods in Boosting Digestion, Metabolism and Immune Health; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2022; pp. 377–417.

- Rahnama, M.; Mehrabani, D.; Japoni, S.; Edjtehadi, M.; Saberi Firoozi, M. The healing effect of licorice (Glycyrrhiza glabra) on Helicobacter pylori infected peptic ulcers. J. Res. Med. Sci. 2013, 18, 532–533.

- Yarnell, E. Herbs for viral respiratory infections. Altern. Complement. Ther. 2018, 24, 35–43.

- Yu, J.J.; Zhang, C.S.; Coyle, M.E.; Du, Y.; Zhang, A.L.; Guo, X.; Xue, C.C.; Lu, C. Compound glycyrrhizin plus conventional therapy for psoriasis vulgaris: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2017, 33, 279–287.

- Biswas, T.K.; Mukherjee, B. Plant medicines of Indian origin for wound healing activity: A review. Int. J. Low. Extrem. Wounds 2003, 2, 25–39.

- Saeedi, M.; Morteza-Semnani, K.; Ghoreishi, M.R. The treatment of atopic dermatitis with licorice gel. J. Dermatol. Treat. 2003, 14, 153–157.

- Sidhu, P.; Shankargouda, S.; Rath, A.; Hesarghatta Ramamurthy, P.; Fernandes, B.; Kumar Singh, A. Therapeutic benefits of liquorice in dentistry. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2020, 11, 82–88.

- Jain, R.; Hussein, M.A.; Pierce, S.; Martens, C.; Shahagadkar, P.; Munirathinam, G. Oncopreventive and oncotherapeutic potential of licorice triterpenoid compound glycyrrhizin and its derivatives: Molecular insights. Pharmacol. Res. 2022, 178, 106138.

- Messier, C.; Epifano, F.; Genovese, S.; Grenier, D. Licorice and its potential beneficial effects in common oro-dental diseases. Oral. Dis. 2012, 18, 32–39.

- Segal, R.; Pisanty, S.; Wormser, R.; Azaz, E.; Sela, M. Anticariogenic activity of licorice and glycyrrhizine I: Inhibition of in vitro plaque formation by Streptococcus mutans. J. Pharm. Sci. 1985, 74, 79–81.

- Edgar, W.M. Reduction in enamel dissolution by liquorice and glycyrrhizinic acid. J. Dent. Res. 1978, 57, 59–64.

- Gedalia, I.; Stabholtz, A.; Lavie, A.; Shapira, L.; Pisanti, S.; Segal, R. The effect of glycyrrhizin on in vitro fluoride uptake by tooth enamel and subsequent demineralization. Clin. Prev. Dent. 1986, 8, 5–9.

- Deutchman, M.; Petrou, I.D.; Mellberg, J.R. Effect of fluoride and glycyrrhizin mouthrinses on artificial caries lesions in vivo. Caries Res. 1989, 23, 206–208.

- Söderling, E.; Karjalainen, S.; Lille, M.; Maukonen, J.; Saarela, M.; Autio, K. The effect of liquorice extract-containing starch gel on the amount and microbial composition of plaque. Clin. Oral. Investig. 2006, 10, 108–113.

- Bodet, C.; La, V.D.; Gafner, S.; Bergeron, C.; Grenier, D. A Licorice Extract Reduces Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Proinflammatory Cytokine Secretion by Macrophages and Whole Blood. J. Periodontol. 2008, 79, 1752–1761.

- La, V.D.; Tanabe, S.-i.; Bergeron, C.; Gafner, S.; Grenier, D. Modulation of Matrix Metalloproteinase and Cytokine Production by Licorice Isolates Licoricidin and Licorisoflavan A: Potential Therapeutic Approach for Periodontitis. J. Periodontol. 2011, 82, 122–128.

- Sharma, S.; Sogi, G.M.; Saini, V.; Chakraborty, T.; Sudan, J. Effect of liquorice (root extract) mouth rinse on dental plaque and gingivitis—A randomized controlled clinical trial. J. Indian. Soc. Periodontol. 2022, 26, 51–57.

- Madan, S.; Kashyap, S.; Mathur, G. Glycyrrhiza glabra: An efficient medicinal plant for control of periodontitis—A randomized clinical trial. J. Int. Clin. Dent. Res. Organ. 2019, 11, 32–35.

- Khan, S.F.; Shetty, B.; Fazal, I.; Khan, A.M.; Mir, F.M.; Moothedath, M.; Reshma, V.J.; Muhamood, M. Licorice as a herbal extract in periodontal therapy. Drug Target. Insights 2023, 17, 70–77.

- Wittschier, N.; Faller, G.; Beikler, T.; Stratmann, U.; Hensel, A. Polysaccharides from Glycyrrhiza glabra L. exert significant anti-adhesive effects against Helicobacter pylori and Porphyromonas gingivalis. Planta Medica 2006, 72, P_238.

- Utsunomiya, T.; Kobayashi, M.; Ito, M.; Pollard, R.B.; Suzuki, F. Glycyrrhizin improves the resistance of MAIDS mice to opportunistic infection of Candida albicans through the modulation of MAIDS-associated type 2 T cell responses. Clin. Immunol. 2000, 95, 145–155.

- Motsei, M.L.; Lindsey, K.L.; van Staden, J.; Jäger, A.K. Screening of traditionally used South African plants for antifungal activity against Candida albicans. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003, 86, 235–241.

- Fatima, A.; Gupta, V.K.; Luqman, S.; Negi, A.S.; Kumar, J.K.; Shanker, K.; Saikia, D.; Srivastava, S.; Darokar, M.P.; Khanuja, S.P. Antifungal activity of Glycyrrhiza glabra extracts and its active constituent glabridin. Phytother. Res. 2009, 23, 1190–1193.

- Lee, J.Y.; Lee, J.H.; Park, J.H.; Kim, S.Y.; Choi, J.Y.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, Y.S.; Kang, S.S.; Jang, E.C.; Han, Y. Liquiritigenin, a licorice flavonoid, helps mice resist disseminated candidiasis due to Candida albicans by Th1 immune response, whereas liquiritin, its glycoside form, does not. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2009, 9, 632–638.

- Messier, C.; Grenier, D. Effect of licorice compounds licochalcone A, glabridin and glycyrrhizic acid on growth and virulence properties of Candida albicans. Mycoses 2011, 54, e801–e806.

- Das, S.K.; Das, V.; Gulati, A.K.; Singh, V.P. Deglycyrrhizinated liquorice in aphthous ulcers. J. Assoc. Physicians India 1989, 37, 647.

- Moghadamnia, A.A.; Motallebnejad, M.; Khanian, M. The efficacy of the bioadhesive patches containing licorice extract in the management of recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Phytother. Res. 2009, 23, 246–250.

- Martin, M.D.; Sherman, J.; van der Ven, P.; Burgess, J. A controlled trial of a dissolving oral patch concerning glycyrrhiza (licorice) herbal extract for the treatment of aphthous ulcers. Gen. Dent. 2008, 56, 206–210; quiz 211-202, 224.

- Burgess, J.A.; van der Ven, P.F.; Martin, M.; Sherman, J.; Haley, J. Review of over-the-counter treatments for aphthous ulceration and results from use of a dissolving oral patch containing glycyrrhiza complex herbal extract. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2008, 9, 88–98.

- Laconi, S.; Madeddu, M.A.; Pompei, R. Autophagy activation and antiviral activity by a licorice triterpene. Phytother. Res. 2014, 28, 1890–1892.

- Partridge, M.; Poswillo, D.E. Topical carbenoxolone sodium in the management of herpes simplex infection. Br. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Surg. 1984, 22, 138–145.

- Segal, R.; Pisanty, S. Glycyrrhizin gel as a vehicle for idoxuridine--I. Clinical investigations. J. Clin. Pharm. Ther. 1987, 12, 165–171.

- Aslani, A.; Zolfaghari, B.; Fereidani, Y. Design, formulation, and evaluation of a herbal gel contains melissa, sumac, licorice, rosemary, and geranium for treatment of recurrent labial herpes infections. Dent. Res. J. 2018, 15, 191–200.

- Nelson, E.O.; Ruiz, G.G.; Kozin, A.F.; Turner, T.C.; Langland, E.V.; Langland, J.O. Resolution of Recurrent Oro-facial Herpes Simplex Using a Topical Botanical Gel: A Case Report. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2020, 93, 277–281.

- Yu, I.C.; Tsai, Y.F.; Fang, J.T.; Yeh, M.M.; Fang, J.Y.; Liu, C.Y. Effects of mouthwash interventions on xerostomia and unstimulated whole saliva flow rate among hemodialysis patients: A randomized controlled study. Int. J. Nurs. Stud. 2016, 63, 9–17.

- Khatab, H.E. Effect of Licorice Mouthwash on Xerostomia among Hemodialysis Patients. Alex. Sci. Nurs. J. 2019, 21, 17–32.

- Nagao, Y.; Sata, M.; Tanikawa, K.; Kameyama, T. A case of oral lichen planus with chronic hepatitis C successfully treated by glycyrrhizin. Kansenshogaku Zasshi. J. Jpn. Assoc. Infect. Dis. 1995, 69, 940–944.

- Nagao, Y.; Sata, M.; Suzuki, H.; Tanikawa, K.; Itoh, K.; Kameyama, T. Effectiveness of glycyrrhizin for oral lichen planus in patients with chronic HCV infection. J. Gastroenterol. 1996, 31, 691–695.

- ARBABI, K.F.; Nosratzehi, T.; Hamishehkar, H.; Delazar, A. Comparison of effectiveness of the bioadhesive pastes containing licorice 5% and topical corticosteroid for the treatment of oral lichen planus: A pilot study. Zahedan J. Res. Med. Sci. 2014, 16, 7–9.

- Inamdar, H.; Sable, D.; Subramaniam, A.V.; Subramaniam, T.; Choudhery, A. Evaluation of efficacy of indigenously prepared formulation of aloe vera, licorice and sesame oil in treatment of oral lichen planus: An in vivo study. J. Adv. Clin. Res. Insights 2015, 2, 237–241.

- Tanabe, S.; Desjardins, J.; Bergeron, C.; Gafner, S.; Villinski, J.R.; Grenier, D. Reduction of bacterial volatile sulfur compound production by licoricidin and licorisoflavan A from licorice. J. Breath. Res. 2012, 6, 016006.

- Chandran, S.; Venkatachalam, K. Effect of Manuka Honey and Licorice Root Extract on the Growth of Porphyromonas gingivalis: An In Vitro Study. J. Emerg. Investig. 2018.

- Das, D.; Agarwal, S.; Chandola, H. Protective effect of Yashtimadhu (Glycyrrhiza glabra) against side effects of radiation/chemotherapy in head and neck malignancies. AYU (Int. Q. J. Res. Ayurveda) 2011, 32, 196–199.

- Najafi, S.; Koujan, S.E.; Manifar, S.; Kharazifard, M.J.; Kidi, S.; Hajheidary, S. Preventive Effect of Glycyrrhiza Glabra Extract on Oral Mucositis in Patients Under Head and Neck Radiotherapy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. J. Dent. 2017, 14, 267–274.

- Ghalayani, P.; Emami, H.; Pakravan, F.; Nasr Isfahani, M. Comparison of triamcinolone acetonide mucoadhesive film with licorice mucoadhesive film on radiotherapy-induced oral mucositis: A randomized double-blinded clinical trial. Asia Pac. J. Clin. Oncol. 2017, 13, e48–e56.

- Ismail, A.A.; Behkite, A.A.; Badria, F.M.; Guemei, A.A. Licorice in prevention of radiation induced mucositis. J. Clin. Oncol. 2004, 22, 8268.

- Chen, G.; Hu, X.; Zhang, W.; Xu, N.; Wang, F.-Q.; Jia, J.; Zhang, W.-F.; Sun, Z.-J.; Zhao, Y.-F. Mammalian target of rapamycin regulates isoliquiritigenin-induced autophagic and apoptotic cell death in adenoid cystic carcinoma cells. Apoptosis 2012, 17, 90–101.

- Cho, J.J.; Chae, J.-I.; Yoon, G.; Kim, K.H.; Cho, J.H.; Cho, S.-S.; Cho, Y.S.; Shim, J.-H. Licochalcone A, a natural chalconoid isolated from Glycyrrhiza inflata root, induces apoptosis via Sp1 and Sp1 regulatory proteins in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Int. J. Oncol. 2014, 45, 667–674.

- Shen, H.; Zeng, G.; Tang, G.; Cai, X.; Bi, L.; Huang, C.; Yang, Y. Antimetastatic effects of licochalcone A on oral cancer via regulating metastasis-associated proteases. Tumor Biol. 2014, 35, 7467–7474.

- Kim, J.-S.; Park, M.-R.; Lee, S.-Y.; Kim, D.K.; Moon, S.M.; Kim, C.S.; Cho, S.S.; Yoon, G.; Im, H.-J.; You, J.S. Licochalcone A induces apoptosis in KB human oral cancer cells via a caspase-dependent FasL signaling pathway. Oncol. Rep. 2014, 31, 755–762.

- Hsia, S.M.; Yu, C.C.; Shih, Y.H.; Yuanchien Chen, M.; Wang, T.H.; Huang, Y.T.; Shieh, T.M. Isoliquiritigenin as a cause of DNA damage and inhibitor of ataxia-telangiectasia mutated expression leading to G2/M phase arrest and apoptosis in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Head Neck 2016, 38, E360–E371.

- Shen, H.; Zeng, G.; Sun, B.; Cai, X.; Bi, L.; Tang, G.; Yang, Y. A polysaccharide from Glycyrrhiza inflata Licorice inhibits proliferation of human oral cancer cells by inducing apoptosis via mitochondrial pathway. Tumor Biol. 2015, 36, 4825–4831.

- James, A.; Gunasekaran, N.; Krishnan, R.; Arunachalam, P.; Mahalingam, R. Anti-fibrotic activity of licorice extract in comparison with colchicine on areca nut-induced fibroblasts: An in vitro study. J. Oral. Maxillofac. Pathol. 2022, 26, 173–178.

- Badr, A.; Omar, N.; Badria, F. A laboratory evaluation of the antibacterial and cytotoxic effect of Liquorice when used as root canal medicament. Int. Endod. J. 2011, 44, 51–58.

- Saha, S.; Dhinsa, G.; Ghoshal, U.; Afzal Hussain, A.N.F.; Nag, S.; Garg, A. Influence of plant extracts mixed with endodontic sealers on the growth of oral pathogens in root canal: An in vitro study. J. Indian Soc. Pedod. Prev. Dent. 2019, 37, 39–45.

- Tamhankar, K.; Dhaded, N.S.; Kore, P.; Nagmoti, J.M.; Hugar, S.M.; Patil, A.C. Comparative Evaluation of Efficacy of Calcium Hydroxide, Propolis, and Glycyrrhiza glabra as Intracanal Medicaments in Root Canal Treatment. J. Contemp. Dent. Pract. 2021, 22, 707–712.

More

Information

Subjects:

Others

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.4K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

20 Nov 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No