| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Duygu AĞAGÜNDÜZ | -- | 4630 | 2023-11-02 17:30:19 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | Meta information modification | 4630 | 2023-11-06 02:02:35 | | |

Video Upload Options

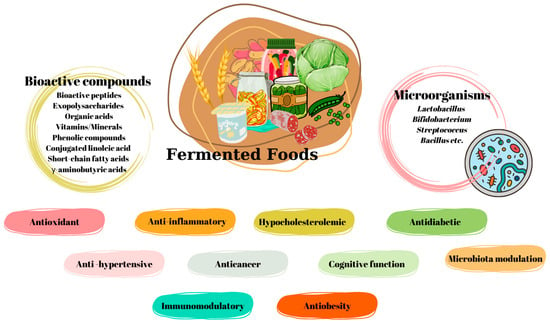

Fermented foods refer to beverages or foods made by carefully regulated microbial growth and the enzymatic conversion of dietary components. Fermented foods have recently become more popular. Studies on fermented foods suggest the types of bacteria and bioactive peptides involved in this process, revealing linkages that may have impacts on human health. By identifying the bacteria and bioactive peptides involved in this process, studies on fermented foods suggest relationships that may have impressions on human health. Fermented foods have been associated with obesity, cardiovascular disease, and type 2 diabetes.

1. Introduction

2. Fermented Dairy Products

2.1. Kefir

2.2. Yogurt

2.3. Cheese

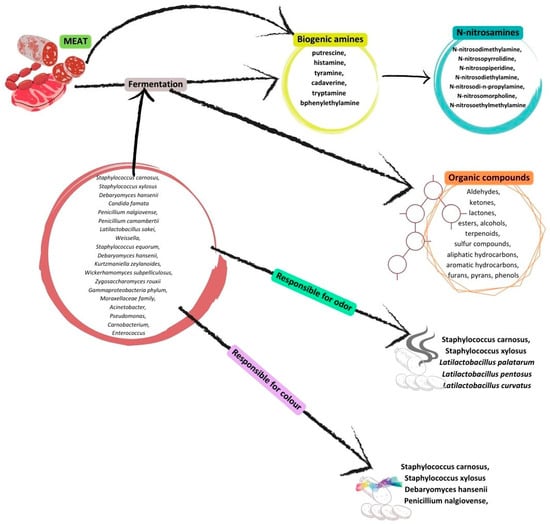

3. Fermented Meats

| Fermented Foods | Certain Bioactive Compounds | Effects on Health | References | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intestine | ||||

| Fermented mutton jerky | x3-2b Lactiplantibacillus plantarum and composite bacteria | Purine content of fermented mutton jerky by x3-2b Lactobacillus plantarum and composite bacteria ↓ In vitro digestion, decreasing purine content by 37x-3 Pediococcus pentosaceus ↑ |

[74] | |

| Cured beef | - | Gastric protein carbonylation ↑ Colonic Ruminococcaceae ↑ Cecal propionate ↑ TBARs and diacetyl in feces ↑ Levels of cecal butyrate, fecal phenol, dimethyl disulfide ↓ Level of fecal carbon disulfide ↑ Colonic Ruminococcaceae ↑ |

[75] | |

| Fermented sausage | Enterococcus faecium CRL 183 | Lactobacillus spp. in ascending colon, transverse colon, and descending colon ↓ Bacteroides spp. in descending colon ↓ Enterobacteriaceae in transverse colon and descending colon ↓ Colonic ammonium ions ↑ Butyric acid concentration in transverse colon, ascending colon, and descending colon ↑ Concentration of propionic acids in ascending colon and transverse colon ↑ Concentration of acetic acid in ascending colon, transverse colon, and descending colon ↓ |

[76] | |

| Fermented sausage | - | Release of free iron in digestive system ↑ Concentration of gastric N-nitrosamine ↑ |

[77] | |

| Fermented sausage | Enterococcus faecium S27 | Transfer of tetracycline resistance determinant (tet(M)) to E. faecium and Enterococcus faecalis ↑ Transfer of Enterococcus faecium’s streptomycin resistance ↑ |

[78] | |

| Fermented sausage | Bologna sausage (a) Dry fermented sausage (b) |

Calcium transporter in Caco-2 cells: in (a) ↑, in (b) ↓ | [79] | |

| Fermented salami | Plant extracts | Phenol and p-cresol in colon ↓ Acetate, propionate, butyrate in colon ↑ Enterobacteriaceae ↓ Bifidobacteriaceae ↑ |

[80] | |

| Fermented fish | Staphylococcus sp. DBOCP6 | Non-hemolytic and non-pathogenic effects against broad and narrow spectrum antibiotics Ability to adhere to the intestinal wall |

[81] | |

| Cardiovascular diseases and ACE-I inhibitory effects | ||||

| - | - | Cardiovascular disease risk, stroke risk ↑ Total mortality risk ↑ |

[82] | |

| Salami Sausage |

Cardiovascular disease risk ↑ | [83] | ||

| - | Cardiovascular disease risk ↑ | [84] | ||

| - | Total stroke incidence ↑ No association between ischemic stroke and coronary heart disease mortality |

[85] | ||

| Bacon Sausage |

- | Cardiovascular death risk ↑ Ischemic heart disease risk ↑ |

[86] | |

| Dry-cured pork ham | - | Levels of total cholesterol, LDL, basal glucose ↓ | [87] | |

| Semi-dry fermented camel sausage | Lactiplantibacillus plantarum KX881772 | Inhibition of ACE ↑ Cytotoxicity activity towards Caco-2 cell line ↑ α-amylase inhibition ↑ α-glucosidase inhibition ↑ |

[88] | |

| Fermented pork sausage | Staphylococcus simulans NJ201 Lactiplantibacillus plantarum CD101 |

ACE inhibition ↑ Superoxide anion scavenging activities ↑ Ferric-reducing antioxidant activity ↑ |

[89] | |

| Dry fermented camel sausage | Staphylococcus xylosus and Lactiplantibacillus plantarum Staphylococcus caarnosus and Latilactobacillus sakei Staphylococcus xylosus and Lactobacillus pentosus |

Antioxidant capacity by <3 kDa peptides ↑ Maximum ACE inhibition by <3 kDa peptides Maximum ACE inhibition in sausages with S. xylosus and L. plantarum |

[90] | |

| Dry-cured ham | - | ACE inhibition ↑ Radical scavenging activity ↑ PAF-AH inhibitory effect ↑ |

[91] | |

| Fermented meat | - | Antioxidant activity against OH-radical by GlnTyr-Pro ↑ | [92] | |

| Dry-fermented sausage | Starter culture (P200S34) and protease (EPg222) | ACE inhibition ↑ Antioxidant activity ↑ |

[93] | |

| - | Risk of cardiovascular mortality, stroke, myocardial infarction via reduction in processed meat ↓ | [94] | ||

| - | Risk of all-mortality cause and cardiometabolic disease via lower consumption ↓ | [95] | ||

| - | Risk of heart failure ↑ | [96] | ||

| Cancer | ||||

| - | Risk of colon cancer, rectal cancer, breast cancer, lung cancer, and colorectal cancer ↑ | [97] | ||

| Ham Sausage Bacon |

- | Breast cancer risk ↑ | [98] | |

| - | Weak positive association with breast cancer | [99] | ||

| - | Breast cancer risk with diet rich in processed meat ↑ | [100] | ||

| Ham Sausage Bacon |

- | Gastric cancer risk ↑ | [101] | |

| Ham Sausage Bacon |

- | Colorectal cancer risk ↑ | [102] | |

| - | Colorectal cancer risk with lower consumption ↓ | [103] | ||

| - | Colorectal cancer risk with lower consumption ↓ | [104] | ||

| - | Colorectal cancer risk ↑ | [105] | ||

| Ham Sausage Bacon |

- | Colorectal cancer risk ↑ | [106] | |

| Ham Sausage Bacon |

- | Colorectal cancer risk ↑ | [107] | |

| - | Colorectal adenoma risk ↑ | [108] | ||

| Ham | - | Risk of renal cell carcinoma ↑ Risk of bladder cancer ↑ |

[109] | |

| Ham Sausage Bacon |

- | Bladder cancer risk ↑ | [110] | |

| Ham Sausage Bacon |

- | Minimal connection to kidney cancer risk | [111] | |

| Ham Salami Sausage Bacon |

- | No association with gliomas | [112] | |

| Risk of hepatocellular carcinoma ↑ | [113] | |||

| Other diseases | ||||

| - | Risk of type 2 diabetes ↑ | [114] | ||

| Bacon Salami Sausages |

- | Risk of diabetes as well as stroke and coronary heart disease ↑ | [115] | |

| - | Risk of type 2 diabetes ↑ | [116] | ||

| - | Type 2 diabetes risk ↑ | [117] | ||

| - | Gestational diabetes mellitus risk ↑ | [118] | ||

| - | No change in Crohn’s disease flares | [119] | ||

| - | Risk of mortality via increase in consumption ↑ | [120] | ||

| - | Mortality risk of all causes (except cancer) and cardiovascular-caused mortality ↑ | [121] | ||

| - | Depression risk ↑ | [122] | ||

| N-Nitrosodimethylamine | No change in glioma | [123] | ||

| Diethylnitrosamine | Probability of hepatocarcinogenesis | [124] | ||

4. Fermented Vegetables and Fruits

4.1. Fermented Vegetables

4.2. Fermented Fruits

5. Fermented Legumes

6. Fermented Cereals

Cereals are also best processed through fermentation, a time-honored technique [177]. The fermenting method is becoming more and more popular due to the growing interest in dietary consumption and nutrition [178]. In Africa, foods made from fermented grains are used as staple foods [179]. Among the most common grains utilized in fermentation are wheat, corn, teff, sorghum, and millet [180]. It is possible to give examples of regionally fermented grain-based dishes like Mawè and Ogi [181]. Utilizing Streptococcus thermophilus during fermentation enhances texture and flavor while also increasing volatile chemicals (diacetyl and acetoin) [182]. The fermentation process decreases the moisture and carbohydrate contents while increasing the total protein and ash contents in corn beverages fermented with Lactobacillus bulgaricus and Streptococcus thermophilus [183]. The traditional Peruvian drink, “Chicha de siete semillas”, is fermented using Streptococcus macedonicus and Leuconoctoc lactis. This fermented cuisine contains a lot of GABAs and is made from grains, pseudograins, and legumes. Streptococcus macedonicus is typically chosen for maize preparation if corn is to be used as a grain source [184]. Amahewu is another type of fermented grain. Amahewu is a fermented oatmeal or beverage made from corn that is mostly enjoyed in South Africa. Depending on the graft type, the type of maize, and the present fermentation circumstances, Amahewu’s nutritional and sensory qualities may change [185]. Bacillus, Arthrobacter, Lactobacillus, Ilyobacter, Clostridium, and Lactococcus are only a few of the numerous and distinct microbial species that are abundant in the fermented rice-based beverage, Chokot, made in India [186]. A popular fermented beverage made from grains called boza is enjoyed in many Balkan nations. Boza is rich in lactic acid bacteria, including Pediococcus parvulus, Lactobacillus parabuchneri, Limosilolactobacillus fermentum, Lactobacillus coryniformis, and Lactobacillus buchneri. Other types of microbiota found in boza, however, include yeasts such Pichia fermentans, Pichia norvegensis, Pichia guilliermondii, and Torulaspora spp. [187]. Boza, a grain-based food, is likewise high in putrescine, spermidine, and tyramine [188]. It has health impacts in addition to enhancing the functional and nutritive value of fermented grain products and satisfying the demands of contemporary consumers for health-promoting products [189].

7. The Other Side of Fermented Foods

References

- Ray, R.; Joshi, V. Fermented Foods: Past, Present and Future. In Microorganisms and Fermentation of Traditional Foods; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2014.

- Marco, M.L.; Sanders, M.E.; Gänzle, M.; Arrieta, M.C.; Cotter, P.D.; De Vuyst, L.; Hill, C.; Holzapfel, W.; Lebeer, S.; Merenstein, D. The International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics (ISAPP) consensus statement on fermented foods. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2021, 18, 196–208.

- Annunziata, G.; Arnone, A.; Ciampaglia, R.; Tenore, G.C.; Novellino, E. Fermentation of foods and beverages as a tool for increasing availability of bioactive compounds. Focus on short-chain fatty acids. Foods 2020, 9, 999.

- Melini, F.; Melini, V.; Luziatelli, F.; Ficca, A.G.; Ruzzi, M. Health-Promoting Components in Fermented Foods: An Up-to-Date Systematic Review. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1189.

- Leeuwendaal, N.K.; Stanton, C.; O’Toole, P.W.; Beresford, T.P. Fermented Foods, Health and the Gut Microbiome. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1527.

- Mathur, H.; Beresford, T.P.; Cotter, P.D. Health Benefits of Lactic Acid Bacteria (LAB) Fermentates. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1679.

- Marco, M.L.; Heeney, D.; Binda, S.; Cifelli, C.J.; Cotter, P.D.; Foligné, B.; Gänzle, M.; Kort, R.; Pasin, G.; Pihlanto, A. Health benefits of fermented foods: Microbiota and beyond. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2017, 44, 94–102.

- Terefe, N.S. Food Fermentation. In Reference Module in Food Science; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016.

- FAO; WHO. Report of a Joint FAO/WHO Expert Consultation on Evaluation of Health and Nutritional Properties of Probiotics in Food including Powder Milk with Live Lactic Acid Bacteria. pp. 1–29. Available online: https://www.fao.org/3/y6398e/y6398e.pdf (accessed on 11 September 2023).

- International Scientific Association for Probiotics and Prebiotics, ISAPP. Probiotics: Dispelling Myths; ISAPP: Sacramento, CA, USA, 2018.

- Ilango, S.; Antony, U. Probiotic microorganisms from non-dairy traditional fermented foods. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 118, 617–638.

- Diez-Ozaeta, I.; Astiazaran, O.J. Fermented foods: An update on evidence-based health benefits and future perspectives. Food Res. Int. 2022, 156, 111133.

- Jaiswal, S.; Pant, T.; Suryavanshi, M.; Antony, U. Microbiological diversity of fermented food Bhaati Jaanr and its antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties: Effect against colon cancer. Food Biosci. 2023, 55, 102822.

- Papadimitriou, C.G.; Vafopoulou-Mastrojiannaki, A.; Silva, S.V.; Gomes, A.-M.; Malcata, F.X.; Alichanidis, E. Identification of peptides in traditional and probiotic sheep milk yoghurt with angiotensin I-converting enzyme (ACE)-inhibitory activity. Food Chem. 2007, 105, 647–656.

- Gu, Y.; Li, X.; Chen, H.; Sun, Y.; Yang, L.; Ma, Y.; Yong Chan, E.C. Antidiabetic effects of multi-species probiotic and its fermented milk in mice via restoring gut microbiota and intestinal barrier. Food Biosci. 2022, 47, 101619.

- Khakhariya, R.; Sakure, A.A.; Maurya, R.; Bishnoi, M.; Kondepudi, K.K.; Padhi, S.; Rai, A.K.; Liu, Z.; Patil, G.B.; Mankad, M.; et al. A comparative study of fermented buffalo and camel milk with anti-inflammatory, ACE-inhibitory and anti-diabetic properties and release of bio active peptides with molecular interactions: In vitro, in silico and molecular study. Food Biosci. 2023, 52, 102373.

- Tunick, M.H.; Van Hekken, D.L. Dairy Products and Health: Recent Insights. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2015, 63, 9381–9388.

- Nongonierma, A.B.; FitzGerald, R.J. Bioactive properties of milk proteins in humans: A review. Peptides 2015, 73, 20–34.

- Shiby, V.K.; Mishra, H.N. Fermented milks and milk products as functional foods—A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2013, 53, 482–496.

- Fernández, M.; Hudson, J.A.; Korpela, R.; de los Reyes-Gavilán, C.G. Impact on human health of microorganisms present in fermented dairy products: An overview. Biomed. Res. Int. 2015, 2015, 412714.

- Lin, M.Y.; Young, C.M. Folate levels in cultures of lactic acid bacteria. Int. Dairy J. 2000, 10, 409–413.

- Van Wyk, J.; Witthuhn, R.C.; Britz, T.J. Optimisation of vitamin B12 and folate production by Propionibacterium freudenreichii strains in kefir. Int. Dairy J. 2011, 21, 69–74.

- Hugenschmidt, S.; Schwenninger, S.M.; Lacroix, C. Concurrent high production of natural folate and vitamin B12 using a co-culture process with Lactobacillus plantarum SM39 and Propionibacterium freudenreichii DF13. Process Biochem. 2011, 46, 1063–1070.

- Ibrahim, S.A.; Gyawali, R.; Awaisheh, S.S.; Ayivi, R.D.; Silva, R.C.; Subedi, K.; Aljaloud, S.O.; Anusha Siddiqui, S.; Krastanov, A. Fermented foods and probiotics: An approach to lactose intolerance. J. Dairy Res. 2021, 88, 357–365.

- Prado, M.R.; Blandón, L.M.; Vandenberghe, L.P.; Rodrigues, C.; Castro, G.R.; Thomaz-Soccol, V.; Soccol, C.R. Milk kefir: Composition, microbial cultures, biological activities, and related products. Front. Microbiol. 2015, 6, 1177.

- Bourrie, B.C.; Willing, B.P.; Cotter, P.D. The Microbiota and Health Promoting Characteristics of the Fermented Beverage Kefir. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 647.

- Yirmibesoglu, S.; Tefon Öztürk, B. Comparing microbiological profiles, bioactivities, and physicochemical and sensory properties of donkey milk kefir and cow milk kefir. Turk. J. Vet. Anim. Sci. 2020, 44, 774–781.

- Aires, R.; Gobbi Amorim, F.; Côco, L.Z.; da Conceição, A.P.; Zanardo TÉ, C.; Taufner, G.H.; Nogueira, B.V.; Vasquez, E.C.; Melo Costa Pereira, T.; Campagnaro, B.P.; et al. Use of kefir peptide (Kef-1) as an emerging approach for the treatment of oxidative stress and inflammation in 2K1C mice. Food Funct. 2022, 13, 1965–1974.

- Maalouf, K.; Baydoun, E.; Rizk, S. Kefir induces cell-cycle arrest and apoptosis in HTLV-1-negative malignant T-lymphocytes. Cancer Manag. Res. 2011, 3, 39–47.

- Erdogan, F.S.; Ozarslan, S.; Guzel-Seydim, Z.B.; Kök Taş, T. The effect of kefir produced from natural kefir grains on the intestinal microbial populations and antioxidant capacities of Balb/c mice. Food Res. Int. 2019, 115, 408–413.

- Ton, A.M.M.; Campagnaro, B.P.; Alves, G.A.; Aires, R.; Côco, L.Z.; Arpini, C.M.; Guerra, E.O.T.; Campos-Toimil, M.; Meyrelles, S.S.; Pereira, T.M.C.; et al. Oxidative Stress and Dementia in Alzheimer’s Patients: Effects of Synbiotic Supplementation. Oxidative Med. Cell Longev. 2020, 2020, 2638703.

- Bellikci-Koyu, E.; Sarer-Yurekli, B.P.; Akyon, Y.; Aydin-Kose, F.; Karagozlu, C.; Ozgen, A.G.; Brinkmann, A.; Nitsche, A.; Ergunay, K.; Yilmaz, E.; et al. Effects of Regular Kefir Consumption on Gut Microbiota in Patients with Metabolic Syndrome: A Parallel-Group, Randomized, Controlled Study. Nutrients 2019, 11, 2089.

- Karaffová, V.; Mudroňová, D.; Mad’ar, M.; Hrčková, G.; Faixová, D.; Gancarčíková, S.; Ševčíková, Z.; Nemcová, R. Differences in Immune Response and Biochemical Parameters of Mice Fed by Kefir Milk and Lacticaseibacillus paracasei Isolated from the Kefir Grains. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 831.

- Chen, H.L.; Tung, Y.T.; Chuang, C.H.; Tu, M.Y.; Tsai, T.C.; Chang, S.Y.; Chen, C.M. Kefir improves bone mass and microarchitecture in an ovariectomized rat model of postmenopausal osteoporosis. Osteoporos. Int. 2015, 26, 589–599.

- Malta, S.M.; Batista, L.L.; Silva, H.C.G.; Franco, R.R.; Silva, M.H.; Rodrigues, T.S.; Correia, L.I.V.; Martins, M.M.; Venturini, G.; Espindola, F.S.; et al. Identification of bioactive peptides from a Brazilian kefir sample, and their anti-Alzheimer potential in Drosophila melanogaster. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 11065.

- Hamet, M.F.; Medrano, M.; Pérez, P.F.; Abraham, A.G. Oral administration of kefiran exerts a bifidogenic effect on BALB/c mice intestinal microbiota. Benef. Microbes 2016, 7, 237–246.

- Youn, H.Y.; Kim, D.H.; Kim, H.J.; Bae, D.; Song, K.Y.; Kim, H.; Seo, K.H. Survivability of Kluyveromyces marxianus Isolated from Korean Kefir in a Simulated Gastrointestinal Environment. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 842097.

- Maccaferri, S.; Klinder, A.; Brigidi, P.; Cavina, P.; Costabile, A. Potential probiotic Kluyveromyces marxianus B0399 modulates the immune response in Caco-2 cells and peripheral blood mononuclear cells and impacts the human gut microbiota in an in vitro colonic model system. Appl. Env. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 956–964.

- Youn, H.Y.; Kim, H.J.; Kim, D.H.; Jang, Y.S.; Kim, H.; Seo, K.H. Gut microbiota modulation via short-term administration of potential probiotic kefir yeast Kluyveromyces marxianus A4 and A5 in BALB/c mice. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 32, 589–598.

- Yanni, A.E.; Kartsioti, K.; Karathanos, V.T. The role of yoghurt consumption in the management of type II diabetes. Food Funct. 2020, 11, 10306–10316.

- Qing, J.; Peng, C.; Chen, H.; Li, H.; Liu, X. Small molecule linoleic acid inhibiting whey syneresis via interact with milk proteins in the fermentation of set yogurt fortified with c9,t11-conjugated linoleic acid. Food Chem. 2023, 429, 136849.

- Le Roy, C.I.; Kurilshikov, A.; Leeming, E.R.; Visconti, A.; Bowyer, R.C.E.; Menni, C.; Falchi, M.; Koutnikova, H.; Veiga, P.; Zhernakova, A.; et al. Yoghurt consumption is associated with changes in the composition of the human gut microbiome and metabolome. BMC Microbiol. 2022, 22, 39.

- Sadrzadeh-Yeganeh, H.; Elmadfa, I.; Djazayery, A.; Jalali, M.; Heshmat, R.; Chamary, M. The effects of probiotic and conventional yoghurt on lipid profile in women. Br. J. Nutr. 2010, 103, 1778–1783.

- Chen, Y.; Feng, R.; Yang, X.; Dai, J.; Huang, M.; Ji, X.; Li, Y.; Okekunle, A.P.; Gao, G.; Onwuka, J.U.; et al. Yogurt improves insulin resistance and liver fat in obese women with nonalcoholic fatty liver disease and metabolic syndrome: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2019, 109, 1611–1619.

- Hasegawa, Y.; Pei, R.; Raghuvanshi, R.; Liu, Z.; Bolling, B.W. Yogurt Supplementation Attenuates Insulin Resistance in Obese Mice by Reducing Metabolic Endotoxemia and Inflammation. J. Nutr. 2023, 153, 703–712.

- Rezazadeh, L.; Gargari, B.P.; Jafarabadi, M.A.; Alipour, B. Effects of probiotic yogurt on glycemic indexes and endothelial dysfunction markers in patients with metabolic syndrome. Nutrition 2019, 62, 162–168.

- Wongrattanapipat, S.; Chiracharoenchitta, A.; Choowongwitthaya, B.; Komsathorn, P.; La-Ongkham, O.; Nitisinprasert, S.; Tunsagool, P.; Nakphaichit, M. Selection of potential probiotics with cholesterol-lowering properties for probiotic yoghurt production. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2022, 28, 353–365.

- Asgharian, H.; Homayouni-Rad, A.; Mirghafourvand, M.; Mohammad-Alizadeh-Charandabi, S. Effect of probiotic yoghurt on plasma glucose in overweight and obese pregnant women: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 59, 205–215.

- Mazani, M.; Nemati, A.; Amani, M.; Haedari, K.; Mogadam, R.A.; Baghi, A.N. The effect of probiotic yoghurt consumption on oxidative stress and inflammatory factors in young females after exhaustive exercise. J. Pak. Med. Assoc. 2018, 68, 1748–1754.

- Mirjalili, M.; Salari Sharif, A.; Sangouni, A.A.; Emtiazi, H.; Mozaffari-Khosravi, H. Effect of probiotic yogurt consumption on glycemic control and lipid profile in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: A randomized controlled trial. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2023, 54, 144–149.

- Odamaki, T.; Kato, K.; Sugahara, H.; Xiao, J.Z.; Abe, F.; Benno, Y. Effect of probiotic yoghurt on animal-based diet-induced change in gut microbiota: An open, randomised, parallel-group study. Benef. Microbes 2016, 7, 473–484.

- Del Carmen, S.; de Moreno de LeBlanc, A.; LeBlanc, J.G. Development of a potential probiotic yoghurt using selected anti-inflammatory lactic acid bacteria for prevention of colitis and carcinogenesis in mice. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2016, 121, 821–830.

- Bintsis, T. Yeasts in different types of cheese. AIMS Microbiol. 2021, 7, 447–470.

- Fröhlich-Wyder, M.T.; Arias-Roth, E.; Jakob, E. Cheese yeasts. Yeast 2019, 36, 129–141.

- Zhang, M.; Dong, X.; Huang, Z.; Li, X.; Zhao, Y.; Wang, Y.; Zhu, H.; Fang, A.; Giovannucci, E.L. Cheese consumption and multiple health outcomes: An umbrella review and updated meta-analysis of prospective studies. Adv. Nutr. 2023, 14, 1170–1186.

- Kurbanova, M.; Voroshilin, R.; Kozlova, O.; Atuchin, V. Effect of Lactobacteria on Bioactive Peptides and Their Sequence Identification in Mature Cheese. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 2068.

- Shafique, B.; Murtaza, M.A.; Hafiz, I.; Ameer, K.; Basharat, S.; Mohamed Ahmed, I.A. Proteolysis and therapeutic potential of bioactive peptides derived from Cheddar cheese. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 11, 4948–4963.

- Helal, A.; Tagliazucchi, D. Peptidomics Profile, Bioactive Peptides Identification and Biological Activities of Six Different Cheese Varieties. Biology 2023, 12, 78.

- Álvarez Ramos, L.; Arrieta Baez, D.; Dávila Ortiz, G.; Carlos Ruiz Ruiz, J.; Manuel Toledo López, V. Antioxidant and antihypertensive activity of Gouda cheese at different stages of ripening. Food Chem. X 2022, 14, 100284.

- Martín-Del-Campo, S.T.; Martínez-Basilio, P.C.; Sepúlveda-Álvarez, J.C.; Gutiérrez-Melchor, S.E.; Galindo-Peña, K.D.; Lara-Domínguez, A.K.; Cardador-Martínez, A. Production of Antioxidant and ACEI Peptides from Cheese Whey Discarded from Mexican White Cheese Production. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 158.

- Timón, M.L.; Andrés, A.I.; Otte, J.; Petrón, M.J. Antioxidant peptides (<3 kDa) identified on hard cow milk cheese with rennet from different origin. Food Res. Int. 2019, 120, 643–649.

- Abedin, M.M.; Chourasia, R.; Chiring Phukon, L.; Singh, S.P.; Kumar Rai, A. Characterization of ACE inhibitory and antioxidant peptides in yak and cow milk hard chhurpi cheese of the Sikkim Himalayan region. Food Chem. X 2022, 13, 100231.

- Dimitrov, Z.; Chorbadjiyska, E.; Gotova, I.; Pashova, K.; Ilieva, S. Selected adjunct cultures remarkably increase the content of bioactive peptides in Bulgarian white brined cheese. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equip. 2015, 29, 78–83.

- Helal, A.; Cattivelli, A.; Conte, A.; Tagliazucchi, D. Effect of Ripening and In Vitro Digestion on Bioactive Peptides Profile in Ras Cheese and Their Biological Activities. Biology 2023, 12, 948.

- Donmez, M.; Kemal Seckin, A.; Sagdic, O.; Simsek, B. Chemical characteristics, fatty acid compositions, conjugated linoleic acid contents and cholesterol levels of some traditional Turkish cheeses. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2005, 56, 157–163.

- Laskaridis, K.; Serafeimidou, A.; Zlatanos, S.; Gylou, E.; Kontorepanidou, E.; Sagredos, A. Changes in fatty acid profile of feta cheese including conjugated linoleic acid. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2013, 93, 2130–2136.

- Santurino, C.; López-Plaza, B.; Fontecha, J.; Calvo, M.V.; Bermejo, L.M.; Gómez-Andrés, D.; Gómez-Candela, C. Consumption of Goat Cheese Naturally Rich in Omega-3 and Conjugated Linoleic Acid Improves the Cardiovascular and Inflammatory Biomarkers of Overweight and Obese Subjects: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Nutrients 2020, 12.

- Koba, K.; Yanagita, T. Health benefits of conjugated linoleic acid (CLA). Obes. Res. Clin. Pr. 2014, 8, e525–e532.

- den Hartigh, L.J. Conjugated Linoleic Acid Effects on Cancer, Obesity, and Atherosclerosis: A Review of Pre-Clinical and Human Trials with Current Perspectives. Nutrients 2018, 11, 370.

- Omer, A.K.; Mohammed, R.R.; Ameen, P.S.M.; Abas, Z.A.; Ekici, K. Presence of Biogenic Amines in Food and Their Public Health Implications: A Review. J. Food Prot. 2021, 84, 1539–1548.

- Herrero-Fresno, A.; Martínez, N.; Sánchez-Llana, E.; Díaz, M.; Fernández, M.; Martin, M.C.; Ladero, V.; Alvarez, M.A. Lactobacillus casei strains isolated from cheese reduce biogenic amine accumulation in an experimental model. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2012, 157, 297–304.

- Smoke, T.; Smoking, I. IARC Monographs on the Evaluation of Carcinogenic Risks to Humans. In Red Meat and Processed Meat; International Agency for Research on Cancer: Lyon, France, 2018.

- Toldrá, F.; Reig, M. Innovations for healthier processed meats. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 22, 517–522.

- Liu, J.; Sun, X.; Zhang, Y.; Jin, Y.; Sun, L.; Chai, X.; Wang, D.; Su, L.; Zhao, L. The impact of different fermenting microbes on residual purine content in fermented lamb jerky following in vitro digestion. Food Chem. 2023, 405, 134997.

- Van Hecke, T.; Vossen, E.; Goethals, S.; Boon, N.; De Vrieze, J.; De Smet, S. In vitro and in vivo digestion of red cured cooked meat: Oxidation, intestinal microbiota and fecal metabolites. Food Res. Int. 2021, 142, 110203.

- Roselino, M.N.; Sakamoto, I.K.; Tallarico Adorno, M.A.; Márcia Canaan, J.M.; de Valdez, G.F.; Rossi, E.A.; Sivieri, K.; Umbelino Cavallini, D.C. Effect of fermented sausages with probiotic Enterococcus faecium CRL 183 on gut microbiota using dynamic colonic model. LWT 2020, 132, 109876.

- Keuleyan, E.; Bonifacie, A.; Sayd, T.; Duval, A.; Aubry, L.; Bourillon, S.; Gatellier, P.; Promeyrat, A.; Nassy, G.; Scislowski, V.; et al. In vitro digestion of nitrite and nitrate preserved fermented sausages—New understandings of nitroso-compounds’ chemical reactivity in the digestive tract. Food Chem. X 2022, 16, 100474.

- Jahan, M.; Zhanel, G.G.; Sparling, R.; Holley, R.A. Horizontal transfer of antibiotic resistance from Enterococcus faecium of fermented meat origin to clinical isolates of E. faecium and Enterococcus faecalis. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 199, 78–85.

- Soto, A.M.; Morales, P.; Haza, A.I.; García, M.L.; Selgas, M.D. Bioavailability of calcium from enriched meat products using Caco-2 cells. Food Res. Int. 2014, 55, 263–270.

- Nissen, L.; Casciano, F.; Di Nunzio, M.; Galaverna, G.; Bordoni, A.; Gianotti, A. Effects of the replacement of nitrates/nitrites in salami by plant extracts on colon microbiota. Food Biosci. 2023, 53, 102568.

- Borah, D.; Gogoi, O.; Adhikari, C.; Kakoti, B.B. Isolation and characterization of the new indigenous Staphylococcus sp. DBOCP06 as a probiotic bacterium from traditionally fermented fish and meat products of Assam state. Egypt. J. Basic. Appl. Sci. 2016, 3, 232–240.

- Iqbal, R.; Dehghan, M.; Mente, A.; Rangarajan, S.; Wielgosz, A.; Avezum, A.; Seron, P.; AlHabib, K.F.; Lopez-Jaramillo, P.; Swaminathan, S.; et al. Associations of unprocessed and processed meat intake with mortality and cardiovascular disease in 21 countries : A prospective cohort study. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 114, 1049–1058.

- Bovalino, S.; Charleson, G.; Szoeke, C. The impact of red and processed meat consumption on cardiovascular disease risk in women. Nutrition 2016, 32, 349–354.

- Damigou, E.; Kosti, R.I.; Anastasiou, C.; Chrysohoou, C.; Barkas, F.; Adamidis, P.S.; Kravvariti, E.; Pitsavos, C.; Tsioufis, C.; Liberopoulos, E.; et al. Associations between meat type consumption pattern and incident cardiovascular disease: The ATTICA epidemiological cohort study (2002−2022). Meat Sci. 2023, 205, 109294.

- de Medeiros, G.; Mesquita, G.X.B.; Lima, S.; Silva, D.F.O.; de Azevedo, K.P.M.; Pimenta, I.; de Oliveira, A.; Lyra, C.O.; Martínez, D.G.; Piuvezam, G. Associations of the consumption of unprocessed red meat and processed meat with the incidence of cardiovascular disease and mortality, and the dose-response relationship: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 1–14.

- Zhang, J.; Hayden, K.; Jackson, R.; Schutte, R. Association of red and processed meat consumption with cardiovascular morbidity and mortality in participants with and without obesity: A prospective cohort study. Clin. Nutr. 2021, 40, 3643–3649.

- Montoro-García, S.; Zafrilla-Rentero, M.P.; Celdrán-de Haro, F.M.; Piñero-de Armas, J.J.; Toldrá, F.; Tejada-Portero, L.; Abellán-Alemán, J. Effects of dry-cured ham rich in bioactive peptides on cardiovascular health: A randomized controlled trial. J. Funct. Foods 2017, 38, 160–167.

- Ayyash, M.; Liu, S.-Q.; Al Mheiri, A.; Aldhaheri, M.; Raeisi, B.; Al-Nabulsi, A.; Osaili, T.; Olaimat, A. In vitro investigation of health-promoting benefits of fermented camel sausage by novel probiotic Lactobacillus plantarum: A comparative study with beef sausages. LWT 2019, 99, 346–354.

- Kong, Y.-w.; Feng, M.-q.; Sun, J. Effects of Lactobacillus plantarum CD101 and Staphylococcus simulans NJ201 on proteolytic changes and bioactivities (antioxidant and antihypertensive activities) in fermented pork sausage. LWT 2020, 133, 109985.

- Mejri, L.; Vásquez-Villanueva, R.; Hassouna, M.; Marina, M.L.; García, M.C. Identification of peptides with antioxidant and antihypertensive capacities by RP-HPLC-Q-TOF-MS in dry fermented camel sausages inoculated with different starter cultures and ripening times. Food Res. Int. 2017, 100, 708–716.

- Li, H.; Wu, J.; Wan, J.; Zhou, Y.; Zhu, Q. Extraction and identification of bioactive peptides from Panxian dry-cured ham with multifunctional activities. LWT 2022, 160, 113326.

- Ohata, M.; Uchida, S.; Zhou, L.; Arihara, K. Antioxidant activity of fermented meat sauce and isolation of an associated antioxidant peptide. Food Chem. 2016, 194, 1034–1039.

- Fernández, M.; Benito, M.J.; Martín, A.; Casquete, R.; Córdoba, J.J.; Córdoba, M.G. Influence of starter culture and a protease on the generation of ACE-inhibitory and antioxidant bioactive nitrogen compounds in Iberian dry-fermented sausage “salchichón”. Heliyon 2016, 2, e00093.

- Zeraatkar, D.; Han, M.A.; Guyatt, G.H.; Vernooij, R.W.M.; El Dib, R.; Cheung, K.; Milio, K.; Zworth, M.; Bartoszko, J.J.; Valli, C.; et al. Red and Processed Meat Consumption and Risk for All-Cause Mortality and Cardiometabolic Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Cohort Studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 171, 703–710.

- Vernooij, R.W.M.; Zeraatkar, D.; Han, M.A.; El Dib, R.; Zworth, M.; Milio, K.; Sit, D.; Lee, Y.; Gomaa, H.; Valli, C.; et al. Patterns of Red and Processed Meat Consumption and Risk for Cardiometabolic and Cancer Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis of Cohort Studies. Ann. Intern. Med. 2019, 171, 732–741.

- Cui, K.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, L.; Mei, X.; Jin, P.; Luo, Y. Association between intake of red and processed meat and the risk of heart failure: A meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 354.

- Farvid, M.S.; Sidahmed, E.; Spence, N.D.; Mante Angua, K.; Rosner, B.A.; Barnett, J.B. Consumption of red meat and processed meat and cancer incidence: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2021, 36, 937–951.

- Anderson, J.J.; Darwis, N.D.M.; Mackay, D.F.; Celis-Morales, C.A.; Lyall, D.M.; Sattar, N.; Gill, J.M.R.; Pell, J.P. Red and processed meat consumption and breast cancer: UK Biobank cohort study and meta-analysis. Eur. J. Cancer 2018, 90, 73–82.

- Alexander, D.D.; Morimoto, L.M.; Mink, P.J.; Cushing, C.A. A review and meta-analysis of red and processed meat consumption and breast cancer. Nutr. Res. Rev. 2010, 23, 349–365.

- Dandamudi, A.; Tommie, J.; Nommsen-Rivers, L.; Couch, S. Dietary Patterns and Breast Cancer Risk: A Systematic Review. Anticancer. Res. 2018, 38, 3209–3222.

- Kim, S.R.; Kim, K.; Lee, S.A.; Kwon, S.O.; Lee, J.K.; Keum, N.; Park, S.M. Effect of Red, Processed, and White Meat Consumption on the Risk of Gastric Cancer: An Overall and Dose–Response Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2019, 11, 826.

- Chan, D.S.; Lau, R.; Aune, D.; Vieira, R.; Greenwood, D.C.; Kampman, E.; Norat, T. Red and processed meat and colorectal cancer incidence: Meta-analysis of prospective studies. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e20456.

- Ubago-Guisado, E.; Rodríguez-Barranco, M.; Ching-López, A.; Petrova, D.; Molina-Montes, E.; Amiano, P.; Barricarte-Gurrea, A.; Chirlaque, M.D.; Agudo, A.; Sánchez, M.J. Evidence Update on the Relationship between Diet and the Most Common Cancers from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition (EPIC) Study: A Systematic Review. Nutrients 2021, 13, 3582.

- Schwingshackl, L.; Schwedhelm, C.; Hoffmann, G.; Knüppel, S.; Laure Preterre, A.; Iqbal, K.; Bechthold, A.; De Henauw, S.; Michels, N.; Devleesschauwer, B.; et al. Food groups and risk of colorectal cancer. Int. J. Cancer 2018, 142, 1748–1758.

- Vieira, A.R.; Abar, L.; Chan, D.S.M.; Vingeliene, S.; Polemiti, E.; Stevens, C.; Greenwood, D.; Norat, T. Foods and beverages and colorectal cancer risk: A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies, an update of the evidence of the WCRF-AICR Continuous Update Project. Ann. Oncol. Off. J. Eur. Soc. Med. Oncol. 2017, 28, 1788–1802.

- Händel, M.N.; Rohde, J.F.; Jacobsen, R.; Nielsen, S.M.; Christensen, R.; Alexander, D.D.; Frederiksen, P.; Heitmann, B.L. Processed meat intake and incidence of colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 2020, 74, 1132–1148.

- Alexander, D.D.; Miller, A.J.; Cushing, C.A.; Lowe, K.A. Processed meat and colorectal cancer: A quantitative review of prospective epidemiologic studies. Eur. J. Cancer Prev. Off. J. Eur. Cancer Prev. Organ. (ECP) 2010, 19, 328–341.

- Aune, D.; Chan, D.S.M.; Vieira, A.R.; Navarro Rosenblatt, D.A.; Vieira, R.; Greenwood, D.C.; Kampman, E.; Norat, T. Red and processed meat intake and risk of colorectal adenomas: A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Cancer Causes Control 2013, 24, 611–627.

- Rosato, V.; Negri, E.; Serraino, D.; Montella, M.; Libra, M.; Lagiou, P.; Facchini, G.; Ferraroni, M.; Decarli, A.; La Vecchia, C. Processed Meat and Risk of Renal Cell and Bladder Cancers. Nutr. Cancer 2018, 70, 418–424.

- Crippa, A.; Larsson, S.C.; Discacciati, A.; Wolk, A.; Orsini, N. Red and processed meat consumption and risk of bladder cancer: A dose-response meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Eur. J. Nutr. 2018, 57, 689–701.

- Alexander, D.D.; Cushing, C.A. Quantitative assessment of red meat or processed meat consumption and kidney cancer. Cancer Detect. Prev. 2009, 32, 340–351.

- Saneei, P.; Willett, W.; Esmaillzadeh, A. Red and processed meat consumption and risk of glioma in adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J. Res. Med. Sci. Off. J. Isfahan Univ. Med. Sci. 2015, 20, 602–612.

- Yu, J.; Liu, Z.; Liang, D.; Li, J.; Ma, S.; Wang, G.; Chen, W. Meat Intake and the Risk of Hepatocellular Carcinoma: A Meta-Analysis of Observational Studies. Nutr. Cancer 2022, 74, 3340–3350.

- Schwingshackl, L.; Hoffmann, G.; Lampousi, A.M.; Knüppel, S.; Iqbal, K.; Schwedhelm, C.; Bechthold, A.; Schlesinger, S.; Boeing, H. Food groups and risk of type 2 diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective studies. Eur. J. Epidemiol. 2017, 32, 363–375.

- Micha, R.; Wallace, S.K.; Mozaffarian, D. Red and processed meat consumption and risk of incident coronary heart disease, stroke, and diabetes mellitus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Circulation 2010, 121, 2271–2283.

- Yang, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, C.; Mao, Z.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, L.; Fan, M.; Cui, S.; Li, L. Meat and fish intake and type 2 diabetes: Dose–response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Diabetes Metab. 2020, 46, 345–352.

- Zhang, R.; Fu, J.; Moore, J.B.; Stoner, L.; Li, R. Processed and Unprocessed Red Meat Consumption and Risk for Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus: An Updated Meta-Analysis of Cohort Studies. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 10788.

- Mijatovic-Vukas, J.; Capling, L.; Cheng, S.; Stamatakis, E.; Louie, J.; Cheung, N.W.; Markovic, T.; Ross, G.; Senior, A.; Brand-Miller, J.C.; et al. Associations of Diet and Physical Activity with Risk for Gestational Diabetes Mellitus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Nutrients 2018, 10, 698.

- Albenberg, L.; Brensinger, C.M.; Wu, Q.; Gilroy, E.; Kappelman, M.D.; Sandler, R.S.; Lewis, J.D. A Diet Low in Red and Processed Meat Does Not Reduce Rate of Crohn’s Disease Flares. Gastroenterology 2019, 157, 128–136.e5.

- Taneri, P.E.; Wehrli, F.; Roa-Díaz, Z.M.; Itodo, O.A.; Salvador, D.; Raeisi-Dehkordi, H.; Bally, L.; Minder, B.; Kiefte-de Jong, J.C.; Laine, J.E.; et al. Association Between Ultra-Processed Food Intake and All-Cause Mortality: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Am. J. Epidemiol. 2022, 191, 1323–1335.

- Wang, X.; Lin, X.; Ouyang, Y.Y.; Liu, J.; Zhao, G.; Pan, A.; Hu, F.B. Red and processed meat consumption and mortality: Dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. Public Health Nutr. 2016, 19, 893–905.

- Nucci, D.; Fatigoni, C.; Amerio, A.; Odone, A.; Gianfredi, V. Red and Processed Meat Consumption and Risk of Depression: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 6686.

- Michaud, D.S.; Holick, C.N.; Batchelor, T.T.; Giovannucci, E.; Hunter, D.J. Prospective study of meat intake and dietary nitrates, nitrites, and nitrosamines and risk of adult glioma12. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2009, 90, 570–577.

- Travis, C.C.; McClain, T.W.; Birkner, P.D. Diethylnitrosamine-induced hepatocarcinogenesis in rats: A theoretical study. Toxicol. Appl. Pharmacol. 1991, 109, 289–304.

- Harris, J.; Tan, W.; Raneri, J.E.; Schreinemachers, P.; Herforth, A. Vegetables for Healthy Diets in Low- and Middle-Income Countries: A Scoping Review of the Food Systems Literature. Food Nutr. Bull. 2022, 43, 232–248.

- Irakoze, M.L.; Wafula, E.N.; Owaga, E. Potential Role of African Fermented Indigenous Vegetables in Maternal and Child Nutrition in Sub-Saharan Africa. Int. J. Food Sci. 2021, 2021, 3400329.

- Lee, S.J.; Jeon, H.S.; Yoo, J.Y.; Kim, J.H. Some Important Metabolites Produced by Lactic Acid Bacteria Originated from Kimchi. Foods 2021, 10, 2148.

- Park, K.Y.; Jeong, J.K.; Lee, Y.E.; Daily, J.W., 3rd. Health benefits of kimchi (Korean fermented vegetables) as a probiotic food. J. Med. Food 2014, 17, 6–20.

- Kim, H.J.; Noh, J.S.; Song, Y.O. Beneficial Effects of Kimchi, a Korean Fermented Vegetable Food, on Pathophysiological Factors Related to Atherosclerosis. J. Med. Food 2018, 21, 127–135.

- Woo, M.; Kim, M.J.; Song, Y.O. Bioactive Compounds in Kimchi Improve the Cognitive and Memory Functions Impaired by Amyloid Beta. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1554.

- Kim, H.J.; Lee, J.S.; Chung, H.Y.; Song, S.H.; Suh, H.; Noh, J.S.; Song, Y.O. 3-(4′-hydroxyl-3′,5′-dimethoxyphenyl)propionic acid, an active principle of kimchi, inhibits development of atherosclerosis in rabbits. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 10486–10492.

- Yun, Y.R.; Kim, H.J.; Song, Y.O. Kimchi methanol extract and the kimchi active compound, 3′-(4′-hydroxyl-3′,5′-dimethoxyphenyl)propionic acid, downregulate CD36 in THP-1 macrophages stimulated by oxLDL. J. Med. Food 2014, 17, 886–893.

- Noh, J.S.; Kim, H.J.; Kwon, M.J.; Song, Y.O. Active principle of kimchi, 3-(4′-hydroxyl-3′,5′-dimethoxyphenyl)propionic acid, retards fatty streak formation at aortic sinus of apolipoprotein E knockout mice. J. Med. Food 2009, 12, 1206–1212.

- Jeong, J.W.; Choi, I.W.; Jo, G.H.; Kim, G.Y.; Kim, J.; Suh, H.; Ryu, C.H.; Kim, W.J.; Park, K.Y.; Choi, Y.H. Anti-Inflammatory Effects of 3-(4′-Hydroxyl-3′,5′-Dimethoxyphenyl)Propionic Acid, an Active Component of Korean Cabbage Kimchi, in Lipopolysaccharide-Stimulated BV2 Microglia. J. Med. Food 2015, 18, 677–684.

- Shankar, T.; Palpperumal, S.; Kathiresan, D.; Sankaralingam, S.; Balachandran, C.; Baskar, K.; Hashem, A.; Alqarawi, A.A.; Abd Allah, E.F. Biomedical and therapeutic potential of exopolysaccharides by Lactobacillus paracasei isolated from sauerkraut: Screening and characterization. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 2943–2950.

- Yu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Li, S.; Li, C.; Li, D.; Yang, Z. Evaluation of probiotic properties of Lactobacillus plantarum strains isolated from Chinese sauerkraut. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2013, 29, 489–498.

- Palani, K.; Harbaum-Piayda, B.; Meske, D.; Keppler, J.K.; Bockelmann, W.; Heller, K.J.; Schwarz, K. Influence of fermentation on glucosinolates and glucobrassicin degradation products in sauerkraut. Food Chem. 2016, 190, 755–762.

- Tai, A.; Fukunaga, K.; Ohno, A.; Ito, H. Antioxidative properties of ascorbigen in using multiple antioxidant assays. Biosci. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2014, 78, 1723–1730.

- Amarakoon, D.; Lee, W.J.; Tamia, G.; Lee, S.H. Indole-3-Carbinol: Occurrence, Health-Beneficial Properties, and Cellular/Molecular Mechanisms. Annu. Rev. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 14, 347–366.

- Dreher, M.L. Whole Fruits and Fruit Fiber Emerging Health Effects. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1833.

- Leitão, M.; Ribeiro, T.; García, P.A.; Barreiros, L.; Correia, P. Benefits of Fermented Papaya in Human Health. Foods 2022, 11, 563.

- Cousin, F.J.; Le Guellec, R.; Schlusselhuber, M.; Dalmasso, M.; Laplace, J.M.; Cretenet, M. Microorganisms in Fermented Apple Beverages: Current Knowledge and Future Directions. Microorganisms 2017, 5, 39.

- Lee, B.H.; Hsu, W.H.; Hou, C.Y.; Chien, H.Y.; Wu, S.C. The Protection of Lactic Acid Bacteria Fermented-Mango Peel against Neuronal Damage Induced by Amyloid-Beta. Molecules 2021, 26, 3503.

- Huang, C.H.; Hsiao, S.Y.; Lin, Y.H.; Tsai, G.J. Effects of Fermented Citrus Peel on Ameliorating Obesity in Rats Fed with High-Fat Diet. Molecules 2022, 27, 8966.

- Wu, C.C.; Huang, Y.W.; Hou, C.Y.; Chen, Y.T.; Dong, C.D.; Chen, C.W.; Singhania, R.R.; Leang, J.Y.; Hsieh, S.L. Lemon fermented products prevent obesity in high-fat diet-fed rats by modulating lipid metabolism and gut microbiota. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 60, 1036–1044.

- Yang, J.; Sun, Y.; Gao, T.; Wu, Y.; Sun, H.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, C.; Zhou, C.; Han, Y.; Tao, Y. Fermentation and Storage Characteristics of “Fuji” Apple Juice Using Lactobacillus acidophilus, Lactobacillus casei and Lactobacillus plantarum: Microbial Growth, Metabolism of Bioactives and in vitro Bioactivities. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 833906.

- Yassunaka Hata, N.N.; Surek, M.; Sartori, D.; Vassoler Serrato, R.; Aparecida Spinosa, W. Role of Acetic Acid Bacteria in Food and Beverages. Food Technol. Biotechnol. 2023, 61, 85–103.

- Perjéssy, J.; Hegyi, F.; Nagy-Gasztonyi, M.; Zalán, Z. Effect of the lactic acid fermentation by probiotic strains on the sour cherry juice and its bioactive compounds. Food Sci. Technol. Int. 2022, 28, 408–420.

- Muhialdin, B.J.; Kadum, H.; Zarei, M.; Meor Hussin, A.S. Effects of metabolite changes during lacto-fermentation on the biological activity and consumer acceptability for dragon fruit juice. LWT 2020, 121, 108992.

- Cirlini, M.; Ricci, A.; Galaverna, G.; Lazzi, C. Application of lactic acid fermentation to elderberry juice: Changes in acidic and glucidic fractions. LWT 2020, 118, 108779.

- Wang, Z.; Feng, Y.; Yang, N.; Jiang, T.; Xu, H.; Lei, H. Fermentation of kiwifruit juice from two cultivars by probiotic bacteria: Bioactive phenolics, antioxidant activities and flavor volatiles. Food Chem. 2022, 373, 131455.

- Ousaaid, D.; Mechchate, H.; Laaroussi, H.; Hano, C.; Bakour, M.; El Ghouizi, A.; Conte, R.; Lyoussi, B.; El Arabi, I. Fruits Vinegar: Quality Characteristics, Phytochemistry, and Functionality. Molecules 2021, 27, 222.

- Bakir, S.; Toydemir, G.; Boyacioglu, D.; Beekwilder, J.; Capanoglu, E. Fruit Antioxidants during Vinegar Processing: Changes in Content and in Vitro Bio-Accessibility. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2016, 17, 1658.

- Budak, H.N.; Guzel-Seydim, Z.B. Antioxidant activity and phenolic content of wine vinegars produced by two different techniques. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2010, 90, 2021–2026.

- Hadi, A.; Pourmasoumi, M.; Najafgholizadeh, A.; Clark, C.C.T.; Esmaillzadeh, A. The effect of apple cider vinegar on lipid profiles and glycemic parameters: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. BMC Complement. Med. Ther. 2021, 21, 179.

- Gheflati, A.; Bashiri, R.; Ghadiri-Anari, A.; Reza, J.Z.; Kord, M.T.; Nadjarzadeh, A. The effect of apple vinegar consumption on glycemic indices, blood pressure, oxidative stress, and homocysteine in patients with type 2 diabetes and dyslipidemia: A randomized controlled clinical trial. Clin. Nutr. ESPEN 2019, 33, 132–138.

- Ousaaid, D.; Laaroussi, H.; Bakour, M.; ElGhouizi, A.; Aboulghazi, A.; Lyoussi, B.; ElArabi, I. Beneficial Effects of Apple Vinegar on Hyperglycemia and Hyperlipidemia in Hypercaloric-Fed Rats. J. Diabetes Res. 2020, 2020, 9284987.

- Halima, B.H.; Sonia, G.; Sarra, K.; Houda, B.J.; Fethi, B.S.; Abdallah, A. Apple Cider Vinegar Attenuates Oxidative Stress and Reduces the Risk of Obesity in High-Fat-Fed Male Wistar Rats. J. Med. Food 2018, 21, 70–80.

- Yagnik, D.; Serafin, V.; Shah, A.J. Antimicrobial activity of apple cider vinegar against Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus and Candida albicans; downregulating cytokine and microbial protein expression. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1732.

- Tripathi, S.; Kumari, U.; Mitra Mazumder, P. Ameliorative effects of apple cider vinegar on neurological complications via regulation of oxidative stress markers. J. Food Biochem. 2020, 44, e13504.

- Shams, F.; Aghajani-Nasab, M.; Ramezanpour, M.; Fatideh, R.H.; Mohammadghasemi, F. Effect of apple vinegar on folliculogenesis and ovarian kisspeptin in a high-fat diet-induced nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in rat. BMC Endocr. Disord. 2022, 22, 330.

- Bolarinwa, I.; Al-Ezzi, M.; Carew, I.; Muhammad, K. Nutritional Value of Legumes in Relation to Human Health: A Review. Adv. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 17, 72–85.

- Cakir, Ö.; Ucarli, C.; TARHAN, Ç.; Pekmez, M.; Turgut-Kara, N. Nutritional and health benefits of legumes and their distinctive genomic properties. Food Sci. Technol. 2019, 39, 1–12.

- Juárez-Chairez, M.F.; Cid-Gallegos, M.S.; Meza-Márquez, O.G.; Jiménez-Martínez, C. Biological functions of peptides from legumes in gastrointestinal health. A review legume peptides with gastrointestinal protection. J. Food Biochem. 2022, 46, e14308.

- Garrido-Galand, S.; Asensio-Grau, A.; Calvo-Lerma, J.; Heredia, A.; Andrés, A. The potential of fermentation on nutritional and technological improvement of cereal and legume flours: A review. Food Res. Int. 2021, 145, 110398.

- Qiao, Y.; Zhang, K.; Zhang, Z.; Zhang, C.; Sun, Y.; Feng, Z. Fermented soybean foods: A review of their functional components, mechanism of action and factors influencing their health benefits. Food Res. Int. 2022, 158, 111575.

- Liu, L.; Chen, X.; Hao, L.; Zhang, G.; Jin, Z.; Li, C.; Yang, Y.; Rao, J.; Chen, B. Traditional fermented soybean products: Processing, flavor formation, nutritional and biological activities. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 62, 1971–1989.

- Kim, I.S.; Hwang, C.W.; Yang, W.S.; Kim, C.H. Current Perspectives on the Physiological Activities of Fermented Soybean-Derived Cheonggukjang. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 5746.

- Kaufman, P.B.; Duke, J.A.; Brielmann, H.; Boik, J.; Hoyt, J.E. A comparative survey of leguminous plants as sources of the isoflavones, genistein and daidzein: Implications for human nutrition and health. J. Altern. Complement. Med. 1997, 3, 7–12.

- Jayachandran, M.; Xu, B. An insight into the health benefits of fermented soy products. Food Chem. 2019, 271, 362–371.

- Nikmaram, N.; Dar, B.N.; Roohinejad, S.; Koubaa, M.; Barba, F.J.; Greiner, R.; Johnson, S.K. Recent advances in γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) properties in pulses: An overview. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2017, 97, 2681–2689.

- Das, G.; Paramithiotis, S.; Sundaram Sivamaruthi, B.; Wijaya, C.H.; Suharta, S.; Sanlier, N.; Shin, H.S.; Patra, J.K. Traditional fermented foods with anti-aging effect: A concentric review. Food Res. Int. 2020, 134, 109269.

- Belobrajdic, D.P.; James-Martin, G.; Jones, D.; Tran, C.D. Soy and Gastrointestinal Health: A Review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1959.

- Das, D.; Sarkar, S.; Borsingh Wann, S.; Kalita, J.; Manna, P. Current perspectives on the anti-inflammatory potential of fermented soy foods. Food Res. Int. 2022, 152, 110922.

- Hu, K.; Huang, H.; Li, H.; Wei, Y.; Yao, C. Legume-Derived Bioactive Peptides in Type 2 Diabetes: Opportunities and Challenges. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1096.

- Das, D.; Sarkar, S.; Bordoloi, J.; Wann, S.B.; Kalita, J.; Manna, P. Daidzein, its effects on impaired glucose and lipid metabolism and vascular inflammation associated with type 2 diabetes. BioFactors 2018, 44, 407–417.

- Tsafrakidou, P.; Michaelidou, A.M.; Biliaderis, C.G. Fermented Cereal-based Products: Nutritional Aspects, Possible Impact on Gut Microbiota and Health Implications. Foods 2020, 9, 734.

- Goksen, G.; Sugra Altaf, Q.; Farooq, S.; Bashir, I.; Cappozzi, V.; Guruk, M.; Lucia Bavaro, S.; Kumar Sarangi, P. A Glimpse into Plant-based Fermented Products Alternative to Animal Based Products: Formulation, Processing, Health Benefits. Food Res. Int. 2023, 173, 113344.

- Hlangwani, E.; Njobeh, P.B.; Chinma, C.E.; Oyedeji, A.B.; Fasogbon, B.M.; Oyeyinka, S.A.; Sobowale, S.S.; Dudu, O.E.; Molelekoa, T.B.J.; Kesa, H.; et al. Chapter 2—African cereal-based fermented products. In Indigenous Fermented Foods for the Tropics; Adebo, O.A., Chinma, C.E., Obadina, A.O., Soares, A.G., Panda, S.K., Gan, R.-Y., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; pp. 15–36.

- Pswarayi, F.; Gänzle, M. African cereal fermentations: A review on fermentation processes and microbial composition of non-alcoholic fermented cereal foods and beverages. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2022, 378, 109815.

- Zannou, O.; Agossou, D.J.; Miassi, Y.; Agani, O.B.; Darino Aisso, M.; Chabi, I.B.; Euloge Kpoclou, Y.; Azokpota, P.; Koca, I. Traditional fermented foods and beverages: Indigenous practices of food processing in Benin Republic. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2022, 27, 100450.

- Kütt, M.-L.; Orgusaar, K.; Stulova, I.; Priidik, R.; Pismennõi, D.; Vaikma, H.; Kallastu, A.; Zhogoleva, A.; Morell, I.; Kriščiunaite, T. Starter culture growth dynamics and sensory properties of fermented oat drink. Heliyon 2023, 9, e15627.

- Ramos, P.I.K.; Tuaño, A.P.P.; Juanico, C.B. Microbial quality, safety, sensory acceptability, and proximate composition of a fermented nixtamalized maize (Zea mays L.) beverage. J. Cereal Sci. 2022, 107, 103521.

- Rebaza-Cardenas, T.; Montes-Villanueva, N.D.; Fernández, M.; Delgado, S.; Ruas-Madiedo, P. Microbiological and physical-chemical characteristics of the Peruvian fermented beverage “Chicha de siete semillas”: Towards the selection of strains with acidifying properties. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2023, 406, 110353.

- Oyeyinka, A.T.; Siwela, M.; Pillay, K. A mini review of the physicochemical properties of amahewu, a Southern African traditional fermented cereal grain beverage. LWT 2021, 151, 112159.

- Bhattacharjee, S.; Sarkar, I.; Sen, G.; Ghosh, C.; Sen, A. Biochemical and Metagenomic sketching of microbial populations in the starter culture of ‘Chokot’, a rice-based fermented liquor of Rabha Tribe in North Bengal, India. Ecol. Genet. Genom. 2023, 29, 100193.

- Osimani, A.; Garofalo, C.; Aquilanti, L.; Milanović, V.; Clementi, F. Unpasteurised commercial boza as a source of microbial diversity. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2015, 194, 62–70.

- Yeğin, S.; Üren, A. Biogenic amine content of boza: A traditional cereal-based, fermented Turkish beverage. Food Chem. 2008, 111, 983–987.

- Zhang, J.; Liu, M.; Zhao, Y.; Zhu, Y.; Bai, J.; Fan, S.; Zhu, L.; Song, C.; Xiao, X. Recent Developments in Fermented Cereals on Nutritional Constituents and Potential Health Benefits. Foods 2022, 11, 2243.

- Li, L.; Wang, P.; Xu, X.; Zhou, G. Influence of various cooking methods on the concentrations of volatile N-nitrosamines and biogenic amines in dry-cured sausages. J. Food Sci. 2012, 77, C560–C565.

- Drabik-Markiewicz, G.; Dejaegher, B.; De Mey, E.; Kowalska, T.; Paelinck, H.; Vander Heyden, Y. Influence of putrescine, cadaverine, spermidine or spermine on the formation of N-nitrosamine in heated cured pork meat. Food Chem. 2011, 126, 1539–1545.

- Gushgari, A.J.; Halden, R.U. Critical review of major sources of human exposure to N-nitrosamines. Chemosphere 2018, 210, 1124–1136.

- WHO. Iarc Monographs on the Identification of Carcinogenic Hazards to Humans; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 1–33.

- Ahmad, W.; Mohammed, G.I.; Al-Eryani, D.A.; Saigl, Z.M.; Alyoubi, A.O.; Alwael, H.; Bashammakh, A.S.; O’Sullivan, C.K.; El-Shahawi, M.S. Biogenic Amines Formation Mechanism and Determination Strategies: Future Challenges and Limitations. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2020, 50, 485–500.

- Doeun, D.; Davaatseren, M.; Chung, M.S. Biogenic amines in foods. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 26, 1463–1474.

- Wójcik, W.; Łukasiewicz, M.; Puppel, K. Biogenic amines: Formation, action and toxicity—A review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2021, 101, 2634–2640.

- Jaguey-Hernández, Y.; Aguilar-Arteaga, K.; Ojeda-Ramirez, D.; Añorve-Morga, J.; González-Olivares, L.G.; Castañeda-Ovando, A. Biogenic amines levels in food processing: Efforts for their control in foodstuffs. Food Res. Int. 2021, 144, 110341.

- Lin, X.; Tang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Sun, Q.; Lv, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wu, C.; Zhu, M.; He, Q.; et al. Sodium Reduction in Traditional Fermented Foods: Challenges, Strategies, and Perspectives. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 8065–8080.

- Bautista-Gallego, J.; Rantsiou, K.; Garrido-Fernández, A.; Cocolin, L.; Arroyo-López, F.N. Salt Reduction in Vegetable Fermentation: Reality or Desire? J. Food Sci. 2013, 78, R1095–R1100.

- Laranjo, M.; Gomes, A.; Agulheiro-Santos, A.C.; Potes, M.E.; Cabrita, M.J.; Garcia, R.; Rocha, J.M.; Roseiro, L.C.; Fernandes, M.J.; Fraqueza, M.J.; et al. Impact of salt reduction on biogenic amines, fatty acids, microbiota, texture and sensory profile in traditional blood dry-cured sausages. Food Chem. 2017, 218, 129–136.

- Dugat-Bony, E.; Sarthou, A.S.; Perello, M.C.; de Revel, G.; Bonnarme, P.; Helinck, S. The effect of reduced sodium chloride content on the microbiological and biochemical properties of a soft surface-ripened cheese. J. Dairy Sci. 2016, 99, 2502–2511.

- Laranjo, M.; Gomes, A.; Agulheiro-Santos, A.C.; Potes, M.E.; Cabrita, M.J.; Garcia, R.; Rocha, J.M.; Roseiro, L.C.; Fernandes, M.J.; Fernandes, M.H.; et al. Characterisation of “Catalão” and “Salsichão” Portuguese traditional sausages with salt reduction. Meat Sci. 2016, 116, 34–42.

- Zhou, Q.; Zang, S.; Zhao, Z.; Li, X. Dynamic changes of bacterial communities and nitrite character during northeastern Chinese sauerkraut fermentation. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2018, 27, 79–85.

- Shen, Q.; Zeng, X.; Kong, L.; Sun, X.; Shi, J.; Wu, Z.; Guo, Y.; Pan, D. Research Progress of Nitrite Metabolism in Fermented Meat Products. Foods 2023, 12, 1485.