Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Carlos Afonso Teixeira | -- | 3154 | 2023-11-02 10:49:41 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | + 1 word(s) | 3155 | 2023-11-03 02:20:45 | | | | |

| 3 | Peter Tang | Meta information modification | 3155 | 2023-11-03 02:21:31 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Marques, A.; Teixeira, C.A. Vine and Wine Sustainability in a Cooperative Ecosystem. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/51089 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Marques A, Teixeira CA. Vine and Wine Sustainability in a Cooperative Ecosystem. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/51089. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Marques, Agostinha, Carlos A. Teixeira. "Vine and Wine Sustainability in a Cooperative Ecosystem" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/51089 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Marques, A., & Teixeira, C.A. (2023, November 02). Vine and Wine Sustainability in a Cooperative Ecosystem. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/51089

Marques, Agostinha and Carlos A. Teixeira. "Vine and Wine Sustainability in a Cooperative Ecosystem." Encyclopedia. Web. 02 November, 2023.

Copy Citation

The world is changing, and climate change has become a serious issue. Organizations, governments, companies, and consumers are becoming more conscious of this impact and are combining their forces to minimize it. Cooperatives have a business model that differs from those in the private or public sector. They operate according to their own principles of cooperation, which makes it difficult to obtain results that are in harmony with the objectives of the organization and the cooperative members.

wine cooperative

sustainability

benchmarks

Environmental science

1. Introduction

In 2015, the United Nations established an agenda for 2030 to 2050 and defined the 17 Goals for Sustainable Development, which aim to improve living conditions; combat poverty, hunger, and social inequity; promote access to water, health, and education; combat climate change; and protect the environment [1][2][3]. In this respect, governments, companies, and organizations have been looking for ways to respond to the United Nations’ challenge. Europe, for its part, has taken the leading role in combating climate change, particularly in the food sector, with the creation of the European Green Deal, whose goals include agriculture that is environmentally sustainable and a fair and healthy food system [4].

Wine production is one of the oldest economic activities, and environmental factors have always affected grape production, forcing people to select grape varieties according to the terroir and the soil in order for greater efficiency [5]. The cultivation of wine has transformed landscapes and has become one of the sectors that contributes most to the economic and social sustainability of communities. It is an integral part of culture, providing many experiences, encouraging tourism, and being a source of pride for communities [2][6].

One of the sectors that most contributes to greenhouse gas emissions is agriculture, with the wine sector accounting for 0.3% of global GHG emissions (considering a bottle of wine leaving a cellar), and promoting sustainable environmental behavior has consequently been the subject of certain policies [7]. Viticulture has a large impact on the environment, as the use of chemical products, soil tillage, irrigation, soil management, and mechanization are all responsible for GHG emissions [4][8].

In 2004, the OIV defined viticultural sustainability as a global strategy for grape and wine production which contributes to the economic sustainability of communities by producing quality products and practicing responsible viticulture. Sustainable viticulture is concerned with risks to the environment, product safety, and consumer health, as well as valuing local heritage, history, landscape, and culture [9][10][11]. There is a growing commitment in agriculture to more sustainable practices [12], not only because of the economy, but also for environmental reasons and the legacy for future generations. Sustainability and the efficient use of environmental, social, and economic resources are becoming increasingly important to wine consumers and winemakers. This is clear from the way that markets and consumers prefer products produced and labeled according to “sustainability indicators or terms”, such as organic, sustainable, natural, free, ecological, etc. [9], because for the consumer, the term “sustainable” is associated with the environment and their carbon footprint. Governments, for their part, have been trying to impose measures that encourage consumers to choose products that are more sustainable, for example, by applying environmental taxes (on carbon) [7] or, in the case of monopolies, restricting products that do not meet sustainability standards.

Wine cooperatives are considered to be organizations with sustainable social and economic development as some of their multiple roles and objectives [13], and they feel pressure not only from consumers, but also from governments and monopoly markets. Ziegler [14] argues that wine cooperatives should have objectives and strategies to ensure circular social and ecological sustainability.

Growing pressure for political reasons and customers looking for sustainable products [5][15] have created the need for winegrowing organizations to develop indicators aimed at the efficient use of water, production methods, the use of phytopharmaceuticals, energy efficiency in the vineyard and winery, the promotion of clean energy rather than fossil fuels, waste management, community impact, and employee well-being [5][16]. This is because, for them, and in contrast to the consumer, sustainability is not only environmental, but also economic and social [9]. In addition, consumers are becoming increasingly aware of the need to be more sustainable, and wine producers need to implement sustainable practices in order to stand out in a market with growing competition [2][6][17].

2. Cooperative Ecosystem

In 1852, Great Britain declared the cooperative a business for the first time [18]. This shows the cooperative tradition in Europe [19]. According to the “Declaration of Cooperative Identity” defined by the International Cooperative Alliance in 1995, “a cooperative is an autonomous association of persons voluntarily united to meet their common economic, social and cultural needs and aspirations through a jointly owned and democratically controlled enterprise” [14][20][21]. Article 2°, paragraph 1 of the Portuguese Cooperative Code defines a cooperative as “collective and autonomous persons, free constituted, with variable capital and composition, which, through the cooperation and mutual help of their members, in compliance with the cooperative principles, aim, on a non-profit basis, to satisfy their economic, social or cultural needs and aspirations” [20][21]. Cooperatives are governed by seven main principles: voluntary and free membership, democratic management by members, economic participation by members, autonomy and independence, education, training and information, cooperation between cooperatives, and interest in the community [21][22]. In other words, cooperatives are socially based people’s enterprises [22], and stand out for promoting social equality, community development, and the well-being of their members [20]. It can be concluded that cooperatives are the best business model for local development, considering the cooperation between citizens and local, regional, and national organizations [20].

Lately, there has been growing interest in the cooperative model, as this business model has proved to be more resilient in times of prolonged economic crises than capitalist companies [13]. Cooperatives favor the maintenance of jobs, preferring to reduce salaries, and the distribution of surpluses is more balanced to meet needs in times of crisis [13]. Historically, there has been an increase in the creation of cooperatives in times of economic and social crisis [20], such as in the production of the liqueur muscatel in Portugal in the 1950s. Ziegler [14] has conducted a study showing that cooperatives are fundamental to the circular economy and its incorporation into regional economies, concerning revalorization, production, consumption, and lasting use.

These organizations are more sensitive to environmental, social, and economic issues due to their cooperative values [12]. Since equality, community development, the well-being of their members, and combating exclusion and poverty among the most disadvantaged classes are at the genesis of the creation of cooperatives, they are an alternative business model to capitalism [13]. This business model helps small producers to create scale, i.e., they are able to sell their products more easily as they gain the capacity to negotiate by volume [20]. However, there are also weaknesses, since a cooperative demands the acceptance of all the production of its cooperative members, without taking into consideration quality or production methods, and can only impose a few rules that benefit those who comply to the detriment of those who do not [19].

Figueiredo [20] defined cooperatives and cooperative members as “social entrepreneurs” who are orientated towards financial independence and sustainable entrepreneurship to create social value for the less privileged. We can therefore say that cooperatives enable the creation of stronger and more sustainable local economies because they reinvest profits, without forgetting social values and their mission [20].

As cooperatives are solutions for local development, agricultural cooperativism is very much in the spotlight, especially when we look at production. According to Figueiredo [13], 41% of the wine produced in Portugal is made by cooperatives, and the numbers are even more impressive when it comes to milk, which accounts for around 62%. This is why agricultural cooperatives are so important, given that they operate at a rural level and contribute to the conservation of these environments and the environment in general [20]. However, like other companies, they must be competitive and create value in order to become economically, socially, and environmentally sustainable [20].

Climate change has been challenging companies to take urgent action to maintain their competitive edge [19]. Some studies show that cooperatives are more proactive on environmental issues than private companies [12], but there is no evidence of their application in agricultural practices, such as in reducing their carbon footprint, water footprint, use of fossil fuels, etc., since there is a lack of documentation or sustainability reports by cooperatives; these reports could not only show their commitment and sustainability strategy, but could also be seen as an internal learning mechanism [14].

Figueiredo is one of the most widely published authors in the field of cooperatives and their dynamics. Analyzing the articles by Ritcher and Figueiredo has provided a better understanding of the fundamentals and the cooperative business model.

3. Difficulties in Respect to Responses from Cooperative Members

The cooperative model depends on the ability of cooperatives to satisfy the ambitions of their members, which sometimes do not meet the principles of cooperativism due to the external and internal pressures that management can face [20]. This disruption can lead to a loss of cooperative identity [20]. For this reason, when results are equal to or better than expected, satisfaction is high and fundamental to maintaining trust, cooperation, and commitment between everyone, cooperatives and cooperators, reducing disputes [20]. In addition, through the difficulties inherent in cooperativism, the wine sector suffers from the effects of demographics and land abandonment. According to Figueiredo’s research [13], the average age of cooperative members is around 60, they are mostly men, and they have low literacy levels. They are also resistant to change, and issues of efficiency and performance are of lesser importance. The great challenge for cooperatives lies in their ability to attract younger members to maintain the sustainability of the organization [13].

Another difficulty is related to one of the cooperative principles, freedom, i.e., there is an “open door” policy, which enables the free entry but also the free exit of members, which leads to problems of opportunism and lack of commitment [20]. Differences between members, like quantity, grape production as a main or secondary activity, acceptance of risk, and organization, contribute to a high degree of heterogeneity between members, which slows down decision-making [18]. Due to this heterogeneity, the challenge is to persuade members to apply sustainability measures [19].

However, it is not only the cooperative members who create difficulties. One of the biggest problems is caused by the cooperative itself: the payment periods for cooperative members are long, never less than 90 days, and often more than two years, which is one of the main reasons why cooperative members leave, as they need immediate liquidity [13].

An advantage of the cooperative system is that when the governance model is orientated to innovation and development, this allows access to innovative technologies and techniques, such as precision agriculture [4]. As well as promoting knowledge, this can make investments in technology accessible to cooperative members, since individual investment would be economically unviable. However, this can be criticized due to differences in objectives between management and cooperative members; one of the most common situations is production vs. quality, with the cooperative looking for quality and the cooperative members seeking production [4].

It is difficult for farmers to measure all the indicators they need to take advantage of in a sustainability framework [23]. The lack of a clear standardization of indicators leaves winegrowers in doubt about which indicators are essential for understanding their company’s level of sustainability, and in responding to market demands [24][25] and determining how to do so. The process is more complicated when applied to wine cooperatives. In a private company, the management board easily defines the objectives to be met by the organization, while in the case of cooperatives, the decision-making capacity of the management board is more limited not only because it is an elected position, but also because of the time limitation for implementing long-term objectives [19]. This difficulty is compounded by the fact that, in general, investments in sustainable measures have a long-term effect and the winegrower needs funding in the short-term, so money is more important [18]. Communication between the board and the members is essential; it is important that the members understand that consumers are now willing to pay more for sustainably produced wine [18].

Faced with the current situation and the analyses carried out in this research, it is necessary to provide cooperatives with tools that support them in materializing their values and responding to the markets [12][18], and that allow the cooperative to prevail in the long-term.

Understanding the dynamics of cooperatives requires an understanding of their strengths and weaknesses. Since cooperatives are created to help a large and heterogeneous number of individuals, this creates many challenges that are not found in private companies.

4. Different Sustainability Benchmarks

Over the years, several sustainable certification benchmarks have emerged which differ from organic, biodynamic, and biological certification [15]. Although they have the same objectives, they are different in terms of methodology [15]. This diversity of benchmarks for certification in the wine sector [25] has led to some markets (export, national) feeling the need to create a set of rules in which the sustainability indicators fit in with greater or lesser importance, as is the case with SystemBolarget, created in Sweden [26], and Sonae’s Producers Club in Portugal.

In the wine sector, there are various models of certification. These can involve the certification of vineyards, wineries, or both [15]. For example, although organic farming has a positive impact on the environment, it has little focus on sustainability [15]. ISO 14001 was designed in the 1990s and is an environmental management system with an auditing program. It is voluntary and includes all economic areas, including agriculture and more specifically the wine sector [15].

In order to regulate the sector in 2020, the OIV (International Organization of Vine and Wine) worked on a guide for implementing the principles of sustainability in viticulture [27]. The sustainable certifications that have subsequently emerged use the OIV’s guidelines in this document as a basis [28]. However, while the key indicators are common across the different benchmarks for certification, the ways in which they are described vary; for example, in calculating the carbon footprint, energy consumption, impact of the carbon footprint on soil, GHG [28], water footprint [29], etc. However, the indicators usually tend to be more descriptive than analytical, making it difficult to determine the questions to be measured and their answers, which is a weakness of the system [23].

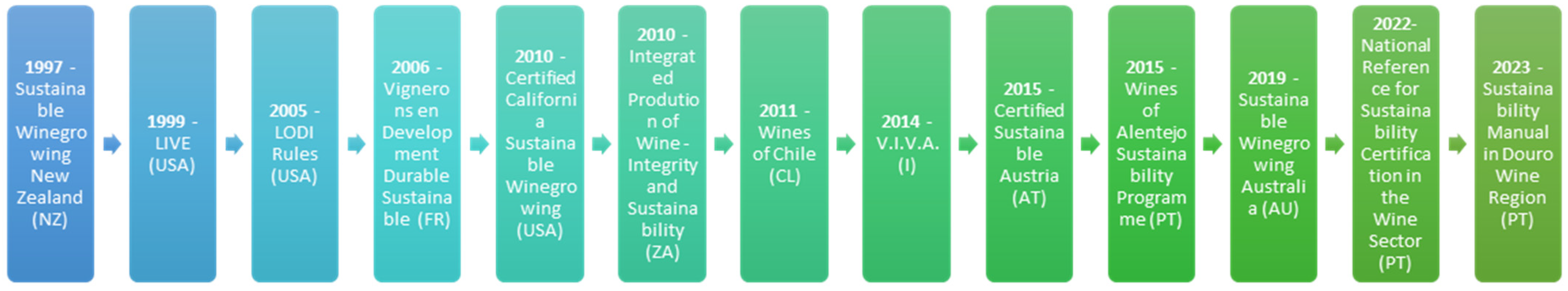

Sustainable certification benchmarks in the wine sector first started in New Zealand in 1997 with the “Sustainable Winegrowing New Zealand” program [30]; others have been emerging [15], most recently in Portugal with ViniPortugal’s “National Reference for Sustainability Certification in the Wine Sector” in 2022 [31] and the IVDP’s “Sustainability Manual for the Douro Wine Region” in 2023 [32] (Figure 1 and Figure 2). Portugal currently has the Alentejo (PSVA), launched in 2015 and promoted by the Alentejo Regional Wine Commission [33].

Figure 1. Timeline for the creation of the different sustainable certification models for the wine sector.

Figure 2. Labels associated with different sustainable certification models in the wine sector.

Some of the best-known sustainable certification benchmarks for the wine sector, created specifically for the vine and wine sector, are described below (Figure 1).

5. Different Sustainability Benchmarks

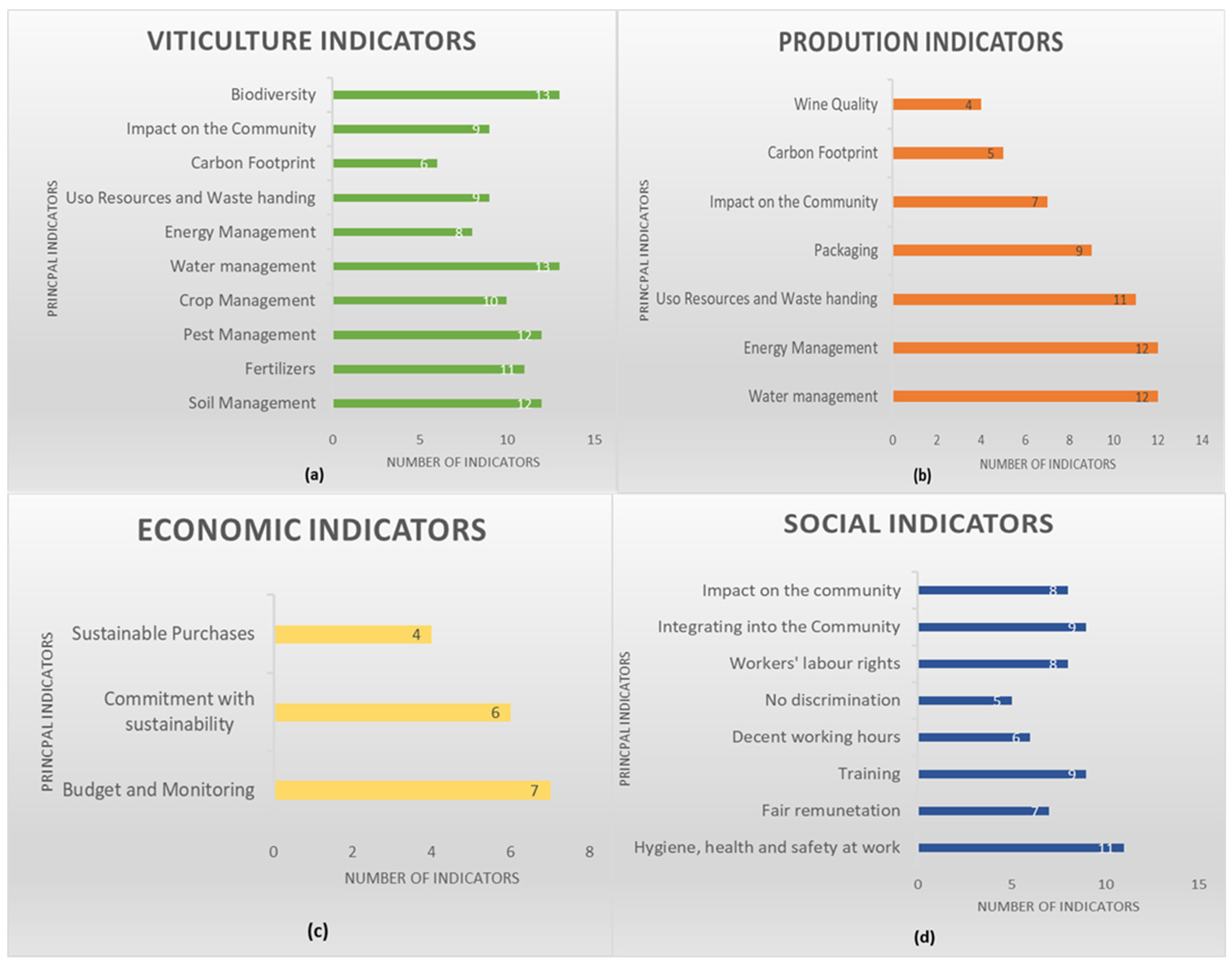

It is possible to analyze which indicators are the most important or eliminatory for each certification model. Furthermore, there has been an evolution in the certification models, with the most recent ones not only being more demanding, but also having more indicators aimed at economic and social sustainability (Figure 3). The first certification models focused more on vineyard, water, and soil aspects [15]. Biodiversity and water management are indicators mentioned in all of the sustainable certification models [10] (Figure 4).

Figure 3. Sustainable certification benchmarks from the oldest to the most recent, showing the most important indicators for each benchmark (legend: green—indicators mentioned in the benchmarks for viticulture; orange—indicators mentioned in the benchmarks for wine production; yellow—economic sustainability indicators mentioned in the benchmarks; blue—social sustainability indicators mentioned in the benchmarks).

Figure 4. The most important sustainability indicators in the different sustainable certification benchmarks: (a) represents the environmental indicators for the vineyard (green color) and the number of benchmarks that measure them, and the most important are biodiversity and water management; (b) represents the environmental indicators for wine production (orange color) and the number of benchmarks that measure them, and again, water management is an important indicator, as is energy management; (c) represents the company’s economic management indicators (yellow color) and the number of benchmarks that measure them, with budget and monitoring being the most relevant; and (d) represents social indicators (blue color) and the company’s relationship with the community and the number of benchmarks that measure them, with hygiene, safety, and health at work being the most mentioned, but others also appear, such as training and integration into the community.

Biodiversity is approached in various ways. In older models, the focus was on maintaining the oldest and regional grape varieties, as well as the ecosystem. The most recent models focus on the vineyard’s ecosystems, such as forest, riparian, small vegetation, and bird nesting sites, and the correct maintenance of these ecosystems. Mulch is becoming increasingly important [31][32][33][34]. In addition to increasing the soil’s ability to retain water, it is a shelter for pest predators and a source of nutrients for the plant, as well as reducing the invasion of undesirable weeds. A good mulch helps to reduce tillage and the use of insecticides, herbicides, and fertilizers, creating greater water retention in the soil and the prevention of soil leaching.

While all the models give importance to the social aspect, it can be seen that “Hygiene, Health and Safety at Work” is present in most of them, as is training. However, these indicators are legal requirements in Europe and the USA, so this is more a way of checking legal compliance, although it can also be seen as an opportunity for improvement.

Below are some graphs (Figure 4) showing which indicators are most relevant to the different benchmarks. Only the most relevant were selected and/or were an eliminating factor in certification.

In this set of graphs (Figure 4), the importance of environmental indicators is clear, especially in the vineyard. Economic indicators are only evaluated in a macro way, which encourages analyses in the direction of economic sustainability. Social indicators are becoming increasingly important, especially on the part of consumers. Consumers prefer products whose production respects human rights, such as fair wages, non-discrimination, and social equity [9][26]. Interaction with the local community is also valued, in terms of the circular economy and minimizing the environmental impact of the activity [5][6][16].

The carbon footprint is an indicator that is not directly addressed in some of the certification benchmarks, but most organizations have online availability so that producers can calculate it [32][34][35][36][37]. However, this is the indicator that consumers recognize most easily, perhaps because it is applicable to all products and is valued more highly than the certification label [12].

There are other certification benchmarks that have not been mentioned, but which are also important for environmental sustainability, such as integrated production (management of natural resources, favoring natural regulation, control of agrochemicals used, and safety times), organic production (determining the type of agrochemicals used, favoring biodiversity, preservation of natural resources) [38] or the Global GAP (benchmark for good agricultural practices) [39]. These models only focus on agricultural practices, but they are also applicable to viticulture.

References

- Chabin, Y.; Rochard, J. UN Sustainable du Development Goals (SDGs) and Corporate Social Responsibility in the wine sector: Concepts and applications. BIO Web Conf. 2023, 56, 03011.

- Ferrer, J.R.; García-Cortijo, M.C.; Pinilla, V.; Castillo-Valero, J.S. The business model and sustainability in the Spanish wine sector. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 330, 129810.

- United Nations. 2023. Available online: https://sdgs.un.org/goals (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Nazzaro, C.; Stanco, M.; Uliano, A.; Lerro, M.; Marotta, G. Collective smart innovations and corporate governance models in Italian wine cooperatives: The opportunities of the farm-to-fork strategy. IFAMA 2022, 25, 723–736.

- Tsalidis, G.A.; Kryona, Z.-P.; Tsirliganis, N. Selecting south European wine based on carbon footprint. Resour. Environ. Sustain. 2022, 9, 100066.

- Martínez-Falcó, J.; Martínez-Falcó, J.; Marco-Lajara, B.; Sánchez-García, E.; Visser, G. Aligning the Sustainable development Goals in the wine industry: A bibliometric analysis. Sustainability 2023, 15, 8172.

- Soregaroli, C.; Ricci, E.C.; Stranieri, S.; Nayga, R.M., Jr.; Capri, E.; Castellari, E. Carbon footprint information, prices, and restaurant wine choices by customers: A natural field experiment. Ecol. Econ. 2021, 186, 107061.

- Litskas, V.D.; Irakleous, T.; Tzortzakis, N.; Stavrinides, M.C. Determining the carbon footprint of indigenous and introduced grape varieties through Life Cycle Assessment using the island of Cyprus as a case study. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 156, 418–425.

- Lamastra, L.; Balderacchi, M.; Di Guardom, A.; Monchiero, M.; Trevsisan, M. A novel fuzzy expert system to assess the sustainability of the viticulture at the wine-estate scale. Sci. Total Environ. 2016, 572, 724–733.

- Marras, S.; Masia, S.; Duce, P.; Spano, D.; Sirca, C. Carbon footprint assessment on a mature vineyard. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2015, 214–215, 350–356.

- Casolani, N.; D’Eusania, M.; Liberatore, L.; Raggi, A.; Petti, L. Life Cycle Assessment in the wine sector: A review on inventory phase. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 376, 134404.

- Calle, F.; González-Moreno, A.; Carrasco, I.; Vargas-Vargas, M. Social economy, environmental proactivity eco-innovation and performance in the Spanish wine sector. Sustainability 2020, 12, 5908.

- Figueiredo, V.; Franco, M. Wine Cooperatives as a form of social entrepreneurship: Empirical evidence about their impact on society. Land Use Policy 2018, 79, 812–821.

- Ziegler, R.; Poirier, C.; Lacasse, M.; Murray, E. Circular Economy and Cooperatives—An Exploratory Survey. Sustainability 2023, 15, 2530.

- Moscovici, D.; Reed, A. Comparing wine sustainability certifications around the word: History, status and opportunity. J. Wine Res. 2018, 29, 1–25.

- D’Ammaro, D.; Capri, E.; Valentino, F.; Grillo, S.; Fiorini, E.; Lamastra, L. A multi-criteria approach to evaluate the sustainability performances of wines: The Italian red wine case study. Sci. Total Environ. 2021, 799, 149446.

- Dressler, M. Sustainable Business Model Design: A Multi-Case Approach Exploring Generic Strategies and Dynamic Capabilities on the Example of German Wine Estates. Sustainability 2023, 15, 3880.

- Ritcher, B.; Hanf, J.H. Cooperatives in wine Industry: Sustainable Management practices and digitalisation. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5543.

- Ritcher, B.; Hanf, J.H. Sustainability as “Value of Cooperatives”—Can (wine) Cooperatives use sustainability as a driver for a brand concept? Sustainability 2021, 13, 12344.

- Figueiredo, V.; Franco, M. Factors influencing cooperator satisfaction: A study applied to wine cooperatives in Portugal. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 191, 15–25.

- Ramos, M.E.; Azevedo, A.; Meira, D.; Malta, M.C. Cooperatives and the Use of Artificial Intelligence: A Critical View. Sustainability 2023, 15, 329.

- CASES. Código Cooperativo Lei nº119/2015 of 31 August Amended by Lei nº66/2017 of 9 August; CASES: Lisboa, Portugal, 2018.

- Whitehead, J. Prioritizing sustainability indicators: Using materiality analysis to guide sustainability assessment and strategy. Bus. Strategy Environ. 2017, 26, 399–412.

- Borsato, E.; Zucchinelli, M.; D’Ammaro, D.; Giubilato, E.; Zabeo, A.; Criscione, P.; Pizzol, L.; Cohen, Y.; Tarolli, P.; Lamastra, L.; et al. Use of multiple indicators to compare sustainability performance of organic vs conventional vineyard management. Sci. Total Envorin. 2020, 711, 135081.

- Merli, R.; Preziosi, M.; Acampora, A. Sustainability experiences in the wine sector: Toward the development of an international indicators system. J. Clean. Prod. 2018, 172, 3791–3805.

- Omsystmenbolaget. 2023. Available online: https://www.omsystembolaget.se/english/sustainability/labels/sustainable-choice/environmental-certifications (accessed on 4 August 2023).

- OIV. 2020. Available online: https://www.oiv.int/public/medias/7601/oiv-viti-641-2020-en.pdf (accessed on 3 August 2023).

- Da Silva, L.P.; Da Silva, J.C.G.E. Evaluation of the carbon footprint of the life cycle of wine production: A review. Clean. Circ. Bioeconomy 2022, 2, 100021.

- Herath, I.; Green, S.; Singh, R.; Horne, D.; Zijpp, S.; Clothier, B. Water footprint of agricultural products: A hydrological assessment for the water footprint of New Zealand’s wines. J. Clean. Prod. 2013, 41, 232–243.

- Discover Sustainable Wine. 2023. Available online: https://discoversustainablewine.com/new-zealand/ (accessed on 5 August 2023).

- Referencial de Sustentabilidade Para o Setor Vitivinícola, ViniPortugal. 2023. Available online: https://www.viniportugal.pt/pt/sustentabilidade/ (accessed on 5 August 2023).

- IVDP. 2023. Available online: https://digital.ivdp.pt/douro-sustentavel/manual-de-sustentabilidade-na-regiao-do-douro-vinhateiro/ (accessed on 6 August 2023).

- PSA. 2023. Available online: https://sustentabilidade.vinhosdoalentejo.pt/pt/certificacao-psva (accessed on 5 August 2023).

- California Sustainable Winegrowing Alliance (CSWA). 2023. Available online: https://www.sustainablewinegrowing.org/sustainable_winegrowing_program.php (accessed on 2 August 2023).

- LIVE. 2023. Available online: https://livecertified.org (accessed on 4 August 2023).

- LODI WINE Growers. 2023. Available online: https://lodigrowers.com/certification/ (accessed on 4 August 2023).

- VIVA. 2022. Available online: https://viticolturasostenibile.org/en/ (accessed on 4 August 2023).

- Direção-Geral de Agricultura e Desenvolvimento Rural. 2023. Available online: https://www.dgadr.gov.pt/producao-integrada2 (accessed on 8 August 2023).

- Global GAP. 2023. Available online: https://www.globalgap.org/pt/ (accessed on 8 August 2023).

More

Information

Subjects:

Environmental Sciences; Agronomy

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

624

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

03 Nov 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No