Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Elzbieta Paszynska | -- | 6072 | 2023-10-31 22:17:26 | | | |

| 2 | Fanny Huang | -3220 word(s) | 2852 | 2023-11-06 02:06:20 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Paszynska, E.; Hernik, A.; Rangé, H.; Amaechi, B.T.; Gross, G.S.; Pawinska, M. Oral Complications of Eating Disorder. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/51017 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Paszynska E, Hernik A, Rangé H, Amaechi BT, Gross GS, Pawinska M. Oral Complications of Eating Disorder. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/51017. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Paszynska, Elzbieta, Amadeusz Hernik, Hélène Rangé, Bennett T. Amaechi, Georgiana S. Gross, Malgorzata Pawinska. "Oral Complications of Eating Disorder" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/51017 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Paszynska, E., Hernik, A., Rangé, H., Amaechi, B.T., Gross, G.S., & Pawinska, M. (2023, October 31). Oral Complications of Eating Disorder. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/51017

Paszynska, Elzbieta, et al. "Oral Complications of Eating Disorder." Encyclopedia. Web. 31 October, 2023.

Copy Citation

Eating disorders (ED) patients were found to present related incidences of oral complications. Studies have reported that the possible course of an ED and comorbidities may be an imbalance in the oral environment. The results showed an association between biological (malnutrition, etc.), behavioral (binge eating episodes, vomiting, acidic diet, poor oral hygiene), and pharmacotherapeutic (addiction, hyposalivation) factors that may threaten oral health. Early diagnosis of the past and present symptoms is essential to eliminate and take control of destructive behaviors. Oral changes need to be tackled with medical insight, and additionally, the perception of dietary interactions is recommended.

eating disorders

nutrition

oral complications

oral hygiene

1. Introduction

Medical professionals, including general practitioners (GPs), dieticians, and dentists, may see eating disorder (ED) patients in their practices. Patients attending medical or dental appointments usually show up for a routine check-up, and EDs can be diagnosed by accident. Those affected by eating disorders are young and often unaware of the seriousness of the complications that can occur as a result of a lack of diagnosis, untreated disease, and dietary errors. Romanos (2012) points out that oral symptoms can appear asymptomatically [1]. Implementing treatment standards, and providing professional medical and psychological help, can happen faster if there is knowledge on and awareness of dietary traps. This increases the chance of not only preventing dangerous health complications manifested in the oral cavity but also improving the prognosis of disease treatment.

2. Eating Disorder Characteristics

2.1. Types of Eating Disorders

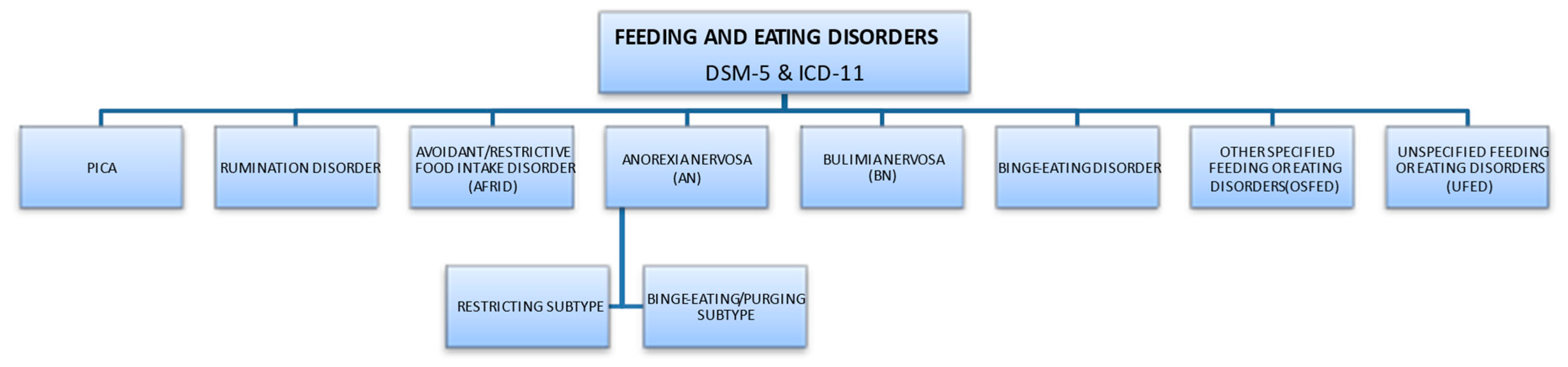

The most important classifications that describe diagnostic criteria are the American Psychiatric Association (APA) guidelines, provided in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM 5th edition, updated in 2013), and the International Classification of Diseases (ICD-11), approved by the World Health Organization (updated 2019) [2][3]. According to ICD-11, this group of diseases falls under behavioral syndromes associated with physiological disorders and physical factors. According to the APA, eating disorders are characterized by ongoing abnormal behaviors related to feeding and eating, followed by changes in food intake or impaired food absorption, and this in turn causes disorders of physical health or social functioning. The symptoms of the disorder allow a clear diagnosis since the diagnosis of a particular disease entity excludes another. Division of EDs according to DSM-5 and ICD-11 subtypes is presented in Figure 1, [2][4].

Figure 1. Division of EDs according to DSM-5 and ICD-11 subtypes.

2.2. ED Risk Factors

Eating disorders are characterized by multiple risk factors, which can be biological, psychological, social, and cultural determinants. Individual theoretical models were considered, referring to socio-cultural determinants (ideal body model, gender role), aspects of personal vulnerability (character and behavioral features, including genetic), family and interpersonal background (disorders occurring in the family, e.g., lack of hierarchy, unclear roles, existence of strong ties, turbulent way of solving problems, perfectionism or overprotection of the family, influences of the environment from the same age group), and influence of traumatic life events (e.g., physical, sexual violence) [5][6]. Risk factors predisposing to the disorder in childhood trigger the first onset of the disease in adolescence [7].

Eating disorders often begin with the selective eating of certain foods or following of specific diets, such as vegetarian diets, that seem easy to accept socially [8]. The image of idealized figures created by social media can also lead to behaviors that promote eating disorders [9]. A contributing factor is perfectionism, an ideal that is an important reference point for the individual [10][11][12]. The following risk groups can be recognized: athletes— including more often female athletes, such as those in cycling, judo, gymnastics, and athletics—and people working in modeling, dance training, the military, catering, and show business [13][14]. Biological backgrounds, e.g., disorders of the serotonergic system, are considered in genetic analysis or as correlations with metabolic and immunological features (including glycemic, lipid) and analysis of the fetal period [7]. Meta-analyses indicate the potential importance of single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) including serotonin receptor gene and serotonin transporter gene (5-HTR2A, 5-HTT), catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) polymorphism (Val158Met), and brain-derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) polymorphism (Val66Met) [15][16]. The heritability in families with mono-dizygotic twins is estimated to be between 48–74% [17]. Genome-wide association studies (GWASs) have identified a chromosome 12 (12q13.2) locus that is relevant to the inheritance of the disease [18].

Researchers’ attention is drawn to changes in both the hunger and satiety centers as well as to the associated regulation of appetite and metabolism. This includes anorexigenic (appetite-reducing) and orexigenic (appetite-stimulating) substances secreted centrally in the central nervous system and peripherally (by adiponectin and enterohormones). Substances that regulate appetite in the short term (e.g., cholecystokinin and other proteins) and long term (hormones leptin, insulin) and enterohormones that interact with the brain–gut axis (e.g., ghrelin, obestatin, neuropeptide B, vaspin phoenixin, spexin, kisspeptin) are involved in the processes of regulating appetite and metabolism [19][20][21][22].

2.3. Epidemiology

Current data show that about 2.9 million people worldwide suffer from anorexia nervosa (AN), with the prevalence in European countries being at the levels of 1–4% (women) and 0.3–0.7% (men) [23][24]. Regarding bulimia nervosa (BN), up to 3% of females and more than 1% of males suffer from this disorder during their lifetime [25]. According to current epidemiological data, EDs are characterized by a long-term course and a high mortality rate [6]. Thus, EDs are an important issue for modern medicine, especially since the incidence rate in Western-civilization countries has been almost declining since the 1970s and the full-blown course is being observed in patients at an increasingly younger age [6][25][26][27].

3. Oral Complications of Eating Disorders

3.1. Oral Hygiene

Until recently, studies have reported conflicting results regarding oral hygiene and periodontal health conditions in ED patients. On the one hand, the ED sufferer exhibits personality traits supposed to lead to overzealous toothbrushing. On the other hand, they suffer from depressive comorbidity with low interest in oral hygiene practices and a higher risk of periodontal diseases. Indeed, periodontal diseases include reversible and irreversible clinical forms of periodontal tissue destruction, known as plaque-induced gingivitis and periodontitis, respectively. The evidence-based pathogenesis of periodontal diseases emphasizes the role of malnutrition [28][29], substance abuse in particular tobacco smoking and alcohol consumption [30], and anxiety [31]. Unbalanced diets with a high consumption of carbohydrates [32][33] and deficiency in vitamins and minerals are frequent in EDs [34]. In addition, mood and anxiety disorders are commonly associated with EDs [35][36]. Hence, ED patients exhibit dietary habits and comorbidities at high risk of periodontal disease. According to the joint classification of the American Academy of Periodontology and the European Federation of Periodontology, plaque-induced gingivitis is an inflammatory response of the gingival tissues resulting from bacterial plaque accumulation located at and below the gingival margin [37]. Managing gingivitis is a primary preventive strategy for periodontitis. Periodontitis is a chronic multifactorial inflammatory disease associated with dysbiotic plaque biofilms and characterized by the progressive destruction of the tooth-supporting apparatus [38]. Its primary features include the loss of periodontal tissue support, manifested through clinical attachment loss (CAL) and radiographically assessed alveolar bone loss; the presence of periodontal pocketing; and gingival bleeding. Without treatment, periodontitis leads to tooth loss.

Case-control studies comparing oral health conditions in EDs with controls have evaluated plaque control with conflicting results. Two studies in the 1990s using the Plaque Index (PI) from Silness and Loe [39], which is a partial recording system prone to bias, found no difference in plaque accumulation between ED and non-ED subjects [40][41]. The oral hygiene level was better in ED outpatients than in non-ED controls in two studies again using non-full-mouth recorded data [42][43]. Poorer plaque control in ED inpatients compared to non-ED controls was shown in two studies [44][45]. In a study with a subgroup analysis, according to the ED diagnosis, plaque control was worse in patients with AN compared to patients with BN and controls with a Plaque Control Record (PCR), measured at 79%, 64%, and 53%, p < 0.01, respectively [44]. Hyposalivation induced by the disease and the psychotropic medications [46] may make plaque control difficult and the lack of salivary mechanical and biological antimicrobial actions can favor plaque accumulation [47][48]. However, in studies, the toothbrushing frequency in people with EDs was not different [49] or even higher than in non-ED controls [44][50].

3.2. Periodontal Health

Several observational studies have assessed the periodontal status of ED patients, mostly those suffering from AN and BN. Gingivitis case definitions used were often heterogeneous among studies based on partial-mouth examination approaches with the Gingival Index (GI) [51], leading to no difference [41] and less gingival inflammation [42][43] in ED patients. However, the two studies with full-mouth bleeding scores showed a higher occurrence of plaque-induced gingivitis in ED patients [44][45]. In addition, two well-designed case-control studies found that ED patients present significantly fewer healthy (no gingival bleeding after probing) sextants, measured by the Community Periodontal Index and Treatment Needs (CPITN) [52], compared with non-ED controls, but found no difference in the number of sextants with periodontitis (probing pocket depth > 3mm) [45][53]. These results are in accordance with those of Pallier and collaborators, who observed a higher CAL, with significantly more sites exhibiting gingival recessions in the ED group in comparison with the control group, but no difference in the number of sites with probing pocket depth [44]. To sum up, ED sufferers are not at risk of periodontitis but are at high risk of plaque-induced gingivitis and gingival recessions.

Gingival recession is defined as the apical shift of the gingival margin with respect to the cementoenamel junction; it is associated with attachment loss and with the exposure of the root surface to the oral environment [54]. People with AN and BN have an increased prevalence of gingival recession compared to subjects without EDs of the same age [44][45]. Gingival recessions have multiple maxillary and mandibular localizations. A whitish appearance of the free gingival margin of the recession is frequent as a sign of chemically induced tissue damage by intrinsic and extrinsic acidity. Atypical localizations such as the palatine surfaces of the upper molars are characteristic of ED patients [55]. Toothbrushing frequency is one of the main risk factors for gingival recession along with improper toothbrushing duration and force [54]. This could explain the more frequent generalized gingival recessions observed in ED patients.

Induced by both tooth wear and gingival recessions, dentinal hypersensitivity is also more frequently reported by patients suffering from EDs than controls [40][50].

3.3. Oral Mucosal Health

Oral mucosal lesions are often observed in EDs. Factors such as malnutrition and associated deficiencies of vitamins or micro- and macronutrients, dehydration, or pathological behaviors such as provoking vomiting, overbiting, and other parafunctions predispose to their occurrence [56]. Stress levels and addictions like smoking are also important [49].

When analyzing the published results, it is important to pay attention to the profile of the study group. Some differences will exist due to the fact that previous authors analyzed subjects with varying proportions of AN, BN, and EDNOS cases; disease durations; and ages. Panico et al. (2018) [57] and Lesar et al. (2022) [58] observed oral lesions in up to 94% of patients. Their locations can be on the lips, which are dry in as many as 76.2% [59], 93.2% [49], or 69% [42] of subjects. In addition, exfoliative cheilitis, angular cheilitis, and labial erythema are very frequently diagnosed [1][49][50][57][58][60]. The mucosa is anemic, thin, and prone to injury. As a result, it is pale, and more often, ulcerations and hemorrhagic lesions appear on it, the occurrence of which are significantly influenced by the provocation of vomiting and the highly acidic content of vomit [49][57][58][59][60].

Patients are more likely to report mouth irritation, diagnosed as Burning Mouth Syndrome (BMS) [1][50][60]. This disease can be determined by the dentist on the basis of subjective symptoms reported by the patient as it is usually not accompanied by any objective local changes in the oral mucosa. Johansson et al. (2012) [42] showed that the chance of experiencing episodes of burning mouth is 14.2 times higher in patients with eating disorders than in healthy individuals. This is suggested to be associated with mucosal atrophy, xerostomia, and the general disruption of oral homeostasis. Individuals with eating disorders have also been observed to have more common symptoms of cheek and lip biting, as well as impressions on the tongue and linea alba, associated with increased stress levels [49][57][58][60]. A weakened immune system and dysbiosis resulting from a breach in tissue continuity will promote a variety of bacterial, viral, and fungal infections, with the typical clinical presentation of these pathogens [61][62][63][64].

3.4. Dental Health

3.4.1. Dental Caries

Eating patterns in EDs that may affect the onset of dental caries include, on the one hand, avoiding entire food groups and certain macronutrients without a medical reason, participating in fad diets to lose weight, and intentionally skipping meals, which may result in nutritional deficiency [65][66]. The low intake of nutrients such as proteins; vitamins A, C, and D; and minerals may enhance their susceptibility to demineralization in carious processes [67]. On the other hand, alternative eating behaviors, such as slowing down the pace of eating, the consumption of large amounts of high-caloric and high-carbohydrate food during binge eating, and engaging in making yourself vomit to control body weight, may contribute to the retention of food debris, the formation of dental plaque on the tooth surface, the lowering of the pH of the oral cavity environment, and the promotion of demineralization, and thus favor dental caries [65].

Additional factors that may promote dental caries in ED patients are alterations in the composition of saliva [68]; a decrease in saliva’s buffer capacity and secretion rate [49][50][69][70], which may be associated with the structural changes in the salivary glands [42][71]; self-induced vomiting or starvation; and the side effects of psychotropic drugs (i.e., antidepressants, appetite suppressants), diuretics or laxatives [46]. Undoubtedly, poor oral hygiene in patients with eating disorders, presumably also resulting from psychological reasons, may be a contributing factor to dental caries [44][72].

Numerous studies have examined the association between dental caries and EDs, applying commonly used caries assessment measures such as caries prevalence or caries severity based on the clinical or (less often) radiographic recordings and expressed by the sum of decayed (D), missing (M), and filled (F) teeth (DMFT index) or tooth surfaces (DMFS index) [42][44][49][50][71][72][73][74][75] or the International Caries Detection and Assessment System (ICDAS-II) system) [76]. However, the results obtained are contradictory and vary between 37% and 80% depending on the type of ED and the qualification criteria adopted for diagnosis [71][72][75][76][77][78]. Some authors demonstrated significantly higher values in terms of the DMFT index and its D and M components in comparison with control groups [44][50][72].

Relationships between the caries index and vomiting frequency are also inconsistent although it is clear that gastric acid along with high-carbohydrate food or beverages may initiate the carious process [79].

It is important to emphasize that there is no single ED-associated factor, but rather, all the above-discussed contributing risk factors may have inputs in ED. The following factors should be considered: cariogenic diet, oral hygiene level, remineralization exposure, and taking certain types of medication [78].

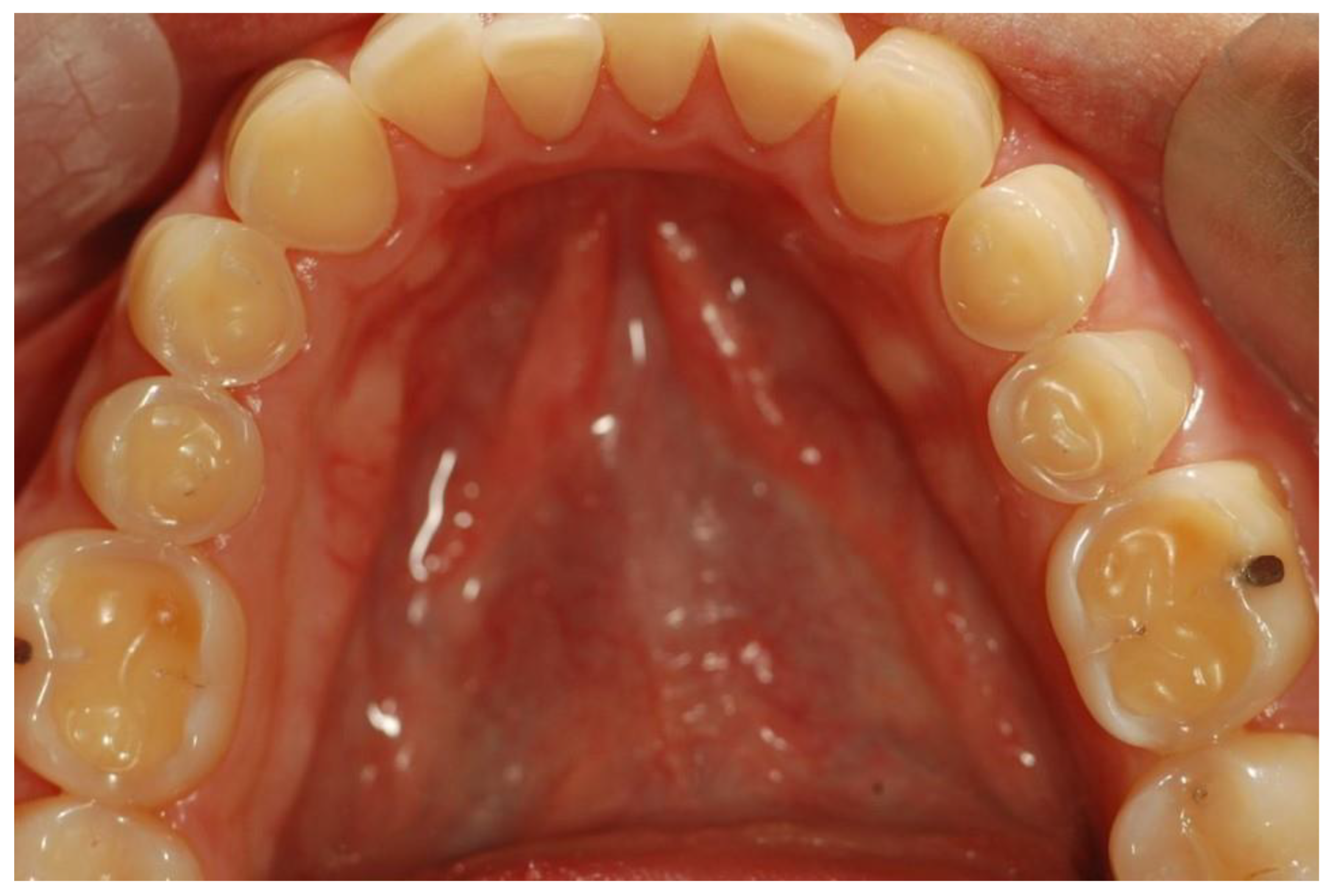

3.4.2. Erosive Tooth Wear

Erosive tooth wear (dental erosion), the irreversible loss of tooth structure due to chemical dissolution by acids not of bacterial origin, is one of the major oral complications of eating disorders [80]. Erosive tooth wear (ETW) is caused by the frequent contact of teeth with acid from either the stomach (gastric acid) or drinking and eating acidic drinks and foods, particularly outside meal times [81]. EDs, particularly BN, can potentially increase the risk for ETW since they may be associated with bingeing on acidic foods and/or drinks followed by vomiting after every meal [42][82][83][84][85]. Some of these patients use these beverages both in the place of normal meals as well as during intense exercise to lose calories [84]. These characteristics are associated with the frequent contact of the teeth with gastric or dietary acids over an extended period of time, with the consequent wearing away of the dental hard tissue through acid demineralization, initially affecting the enamel, and with the progression to an advanced stage, dentin is exposed (Figure 2 and Figure 3). The exposure of dentin may result in dentin hypersensitivity in response to external stimuli of a cold, hot, tactile, or osmotic nature. The acid of gastric juice brought up due to vomiting, the pH of which can be as low as 1, causes the wear of the palatal surfaces of upper incisors (Figure 2), and with lesion progression, the lingual surfaces of premolars and molars become affected, and in more advanced stages, the process extends to the occlusal surfaces of molars and to the facial surfaces of all teeth [85][86]. Erosion due to dietary acid, with pH ranging from 2.7 to 3.8, has no specific distribution pattern, but depends on factors such as the method of application. Thus, EDs in combination with vomiting are associated with an increased occurrence, severity, and risk of dental erosion [85]. The reported prevalence of ETW among eating disorder patients, particularly those with BN, varies among countries and ranges from 42 to 98% [85].

Figure 2. Palatal surfaces of maxillary teeth affected by erosive tooth wear (Courtsey Amaechi BT, UTHSA, San Antonio, TX, USA).

Figure 3. Occlusal surfaces of mandibular teeth affected by erosive teeth wear (Courtsey Amaechi BT, UTHSA, San Antonio, TX, USA).

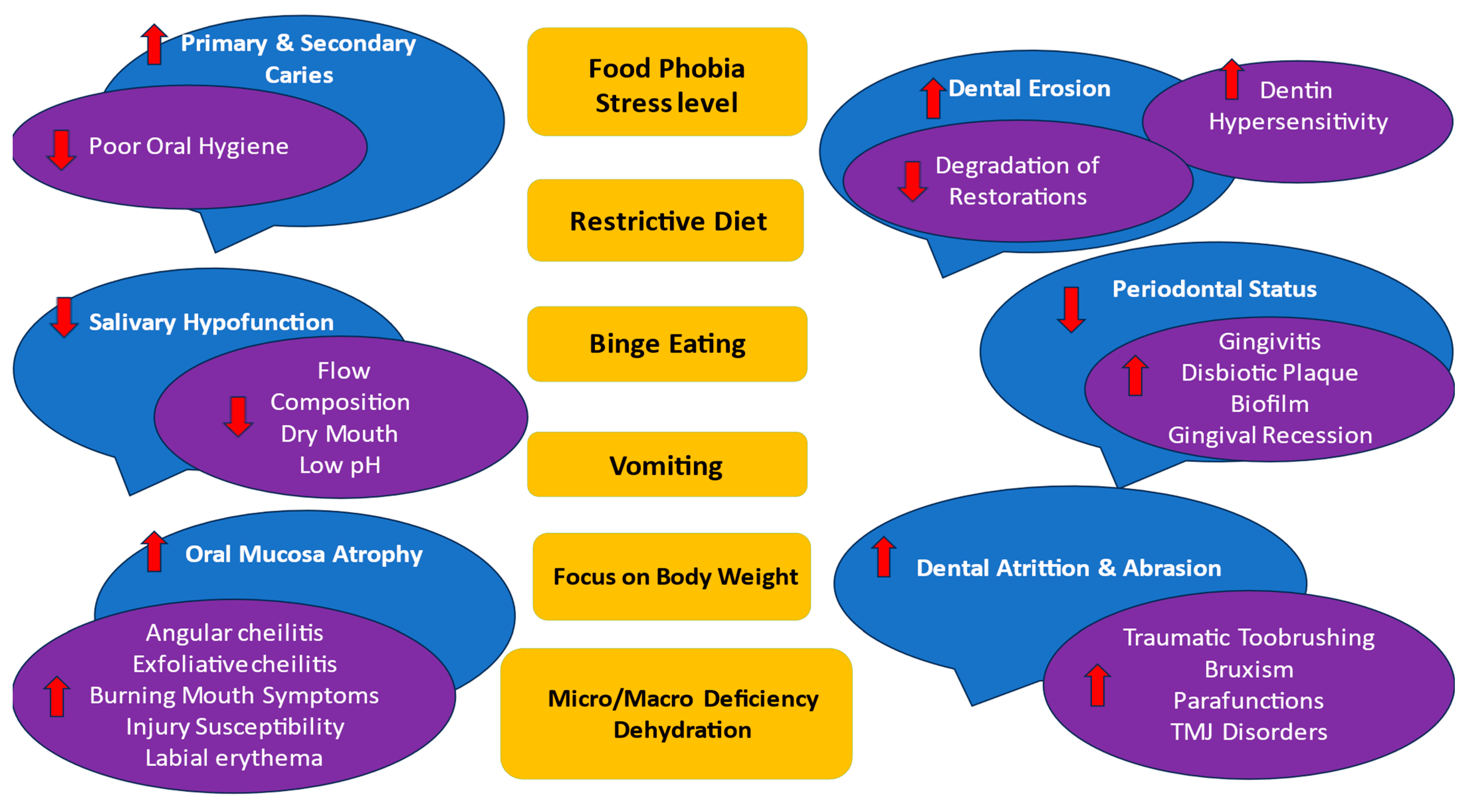

Main ED’s symptoms and oral effects are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4. EDs’ main symptoms (in yellow) and oral effects (in blue and purple). The following factors may influence any oral complications: subtype of AN, BN, and EDNOS according to nutritional behaviors; vomiting frequency; disease duration; age and sex of the patient; general health status; pharmacotherapy and their side effects to salivation; and psychosocial profile; as well as cariogenic/acidic diet, individual oral hygiene, and remineralization exposure. Abbreviations: ↑↓ means the ED symptoms increase the oral effect/decrease the oral effect.

References

- Romanos, G.E.; Javed, F.; Romanos, E.B.; Williams, R.C. Oro-facial manifestations in patients with eating disorders. Appetite 2012, 59, 499–504.

- American Psychiatric Association. Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th ed.; American Psychiatric Publishing: Arlington, TX, USA, 2013.

- International Classification of Diseases, Eleventh Revision (ICD-11), World Health Organization (WHO) 2019/2021. Licensed under Creative Commons Attribution-NoDerivatives 3.0 IGO Licence (CC BY-ND 3.0 IGO). Available online: https://icd.who.int/browse11 (accessed on 1 July 2023).

- Reed, G.M.; First, M.B.; Kogan, C.S.; Hyman, S.E.; Gureje, O.; Gaebel, W.; Maj, M.; Stein, D.J.; Maercker, A.; Tyrer, P.; et al. Innovations and changes in the ICD-11 classification of mental, behavioural and neurodevelopmental disorders. World Psychiatry 2019, 18, 3–19.

- Özbaran, N.B.; Yılancıoğlu, H.Y.; Tokmak, S.H.; YuluğTaş, B.; Çek, D.; Bildik, T. Changes in the psychosocial and clinical profiles of anorexia nervosa patients during the pandemic. Front. Psychiatry 2023, 14, 1207526.

- Jagielska, G.; Kacperska, I. Outcome, comorbidity and prognosis in anorexia nervosa. Psychiatr. Pol. 2017, 51, 205–218.

- Grzelak, T.; Dutkiewicz, A.; Paszynska, E.; Dmitrzak-Weglarz, M.; Slopien, A.; Tyszkiewicz-Nwafor, M. Neurobiochemical and psychological factors influencing the eating behaviors and attitudes in anorexia nervosa. J. Physiol. Biochem. 2017, 73, 297–305.

- Bardone-Cone, A.M.; Fitzsimmons-Craft, E.E.; Harney, M.B.; Maldonado, C.R.; Lawson, M.A.; Smith, R.; Robinson, D.P. The inter-relationships between vegetarianism and eating disorders among females. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2012, 112, 1247–1252.

- Ferguson, C.J.; Muñoz, M.E.; Garza, A.; Galindo, M. Concurrent and prospective analyses of peer, television and social media influences on body dissatisfaction, eating disorder symptoms and life satisfaction in adolescent girls. J. Youth Adolesc. 2014, 43, 1–14.

- Antczak, A.J.; Brininger, T.L. Diagnosed eating disorders in the U.S. Military: A nine year review. Eat. Disord. 2008, 16, 363–377.

- Filaire, E.; Rouveix, M.; Pannafieux, C.; Ferrand, C. Eating Attitudes, Perfectionism and Body-esteem of Elite Male Judoists and Cyclists. J. Sports Sci. Med. 2007, 6, 50–57.

- Penniment, K.J.; Egan, S.J. Perfectionism and learning experiences in dance class as risk factors for eating disorders in dancers. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2012, 20, 13–22.

- Lindberg, L.; Hjern, A. Risk factors for anorexia nervosa: A national cohort study. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2003, 34, 397–408.

- McClelland, L.; Crisp, A. Anorexia nervosa and social class. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2001, 29, 150–156.

- Dmitrzak-Weglarz, M.; Moczko, J.; Skibinska, M.; Slopien, A.; Tyszkiewicz, M.; Pawlak, J.; Zaremba, D.; Szczepankiewicz, A.; Rajewski, A.; Hauser, J. The study of candidate genes related to the neurodevelopmental hypothesis of anorexia nervosa: Classical association study versus decision tree. Psychiatry Res. 2013, 30, 117–121.

- Dmitrzak-Weglarz, M.; Szczepankiewicz, A.; Slopien, A.; Tyszkiewicz, M.; Maciukiewicz, M.; Zaremba, D.; Twarowska-Hauser, J. Association of the glucocorticoid receptor gene polymorphisms and their interaction with stressful life events in Polish adolescent girls with anorexia nervosa. Psychiatr. Danub. 2016, 28, 51–57.

- Baker, J.H.; Schaumberg, K.; Munn-Chernoff, M.A. Genetics of Anorexia Nervosa. Curr. Psychiatry Rep. 2017, 19, 84.

- Boraska, V.; Franklin, C.S.; Floyd, J.A.; Thornton, L.M.; Huckins, L.M.; Southam, L.; Rayner, N.W.; Tachmazidou, I.; Klump, K.L.; Treasure, J. A genome-wide association study of anorexia nervosa. Mol. Psychiatry 2014, 19, 1085–1094.

- Janas-Kozik, M.; Stachowicz, M.; Krupka-Matuszczyk, I.; Szymszal, J.; Krysta, K.; Janas, A.; Rybakowski, J.K. Plasma levels of leptin and orexin a in the restrictive type of anorexia nervosa. Regul. Pept. 2011, 168, 5–9.

- Pałasz, A.; Tyszkiewicz-Nwafor, M.; Suszka-Świtek, A.; Bacopoulou, F.; Dmitrzak-Węglarz, M.; Dutkiewicz, A.; Słopień, A.; Janas-Kozik, M.; Wilczyński, K.M.; Filipczyk, Ł.; et al. Longitudinal study on novel neuropeptides phoenixin, spexin and kisspeptin in adolescent inpatients with anorexia nervosa—Association with psychiatric symptoms. Nutr. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 896–906.

- Grzelak, T.; Tyszkiewicz-Nwafor, M.; Dutkiewicz, A.; Mikulska, A.A.; Dmitrzak-Weglarz, M.; Slopien, A.; Czyzewska, K.; Paszynska, E. Neuropeptide B and Vaspinas New Biomarkers in Anorexia Nervosa. Biomed. Res. Int. 2018, 10, 9727509.

- Tyszkiewicz-Nwafor, M.; Jowik, K.; Paszynska, E.; Dutkiewicz, A.; Słopien, A.; Dmitrzak-Weglarz, M. Expression of immune-related proteins and their association with neuropeptides in adolescent patients with anorexia nervosa. Neuropeptides 2022, 91, 102214.

- Vos, T.; Allen, C.; Arora, M.; Barber, R.M.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Brown, A.; Carter, A.; Casey, D.C.; Charlson, F.J.; Chen, A.Z.; et al. Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 310 diseases and injuries, 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet 2016, 388, 1545–1602.

- Keski-Rahkonen, A.; Mustelin, L. Epidemiology of eating disorders in Europe: Prevalence, incidence, comorbidity, course, consequences, and risk factors. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2016, 29, 340–345.

- van Eeden, A.E.; van Hoeken, D.; Hoek, H.W. Incidence, prevalence and mortality of anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa. Curr. Opin. Psychiatry 2021, 34, 515–524.

- van Noort, B.M.; Lohmar, S.K.; Pfeiffer, E.; Lehmkuhl, U.; Winter, S.M.; Kappel, V. Clinical characteristics of early onset anorexia nervosa. Eur. Eat. Disord. Rev. 2018, 26, 519–525.

- Bryant-Waugh, R. Feeding and Eating Disorders in Children. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2019, 42, 157–167.

- Casarin, M.; da Silveira, T.M.; Bezerra, B.; Pirih, F.Q.; Pola, N.M. Association between different dietary patterns and eating disorders and periodontal diseases. Front. Oral Health 2023, 22, 1152031.

- Dommisch, H.; Kuzmanova, D.; Jönsson, D.; Grant, M.; Chapple, I. Effect of micronutrient malnutrition on periodontal disease and periodontal therapy. Periodontol. 2000 2018, 78, 129–153.

- Kumar, P.S. Interventions to prevent periodontal disease in tobacco-, alcohol-, and drug-dependent individuals. Periodontol. 2000 2020, 84, 84–101.

- Aggarwal, K.; Gupta, J.; Kaur, R.K.; Bansal, D.; Jain, A. Effect of anxiety and psychologic stress on periodontal health: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Quintessence Int. 2022, 53, 144–154.

- Liew, V.P.; Frisken, K.W.; Touyz, S.W.; Beumont, P.J.; Williams, H. Clinical and microbiological investigations of anorexia nervosa. Aust. Dent. J. 1991, 36, 435–441.

- Hellström, I. Oral complications in anorexia nervosa. Scand. J. Dent. Res. 1977, 85, 71–86.

- Hanachi, M.; Dicembre, M.; Rives-Lange, C.; Ropers, J.; Bemer, P.; Zazzo, J.F.; Poupon, J.; Dauvergne, A.; Melchior, J.C. Micronutrients Deficiencies in 374 Severely Malnourished Anorexia Nervosa Inpatients. Nutrients 2019, 5, 792.

- Godart, N.T.; Flament, M.F.; Perdereau, F.; Jeammet, P. Comorbidity between eating disorders and anxiety disorders: A review. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2002, 32, 253–270.

- Godart, N.T.; Perdereau, F.; Rein, Z.; Berthoz, S.; Wallier, J.; Jeammet, P.H.; Flament, M.F. Comorbidity studies of eating disorders and mood disorders. Critical review of the literature. J. Affect. Disord. 2007, 97, 37–49.

- Murakami, S.; Mealey, B.L.; Mariotti, A.; Chapple, I.L.C. Dental plaque-induced gingival conditions. J. Periodontol. 2018, 89, 17–27.

- Papapanou, P.; Sanz, M.; Buduneli, N.; Dietrich, T.; Feres, M.; Fine, D.H.; Flemmig, T.F.; Garcia, R.; Giannobile, W.V.; Graziani, F.; et al. Periodontitis: Consensus report of workgroup 2 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, 162–170.

- Silness, J.; Loe, H. Periodontal Disease in Pregnancy. II. Correlation between Oral Hygiene and Periodontal Condtion. Acta Odontol. Scand. 1964, 22, 121–135.

- Altschuler, B.D.; Dechow, P.C.; Waller, D.A.; Hardy, B.W. An investigation of the oral pathologies occurring in bulimia nervosa. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1990, 9, 191–199.

- Milosevic, A.; Slade, P.D. The orodental status of anorexics and bulimics. Br. Dent. J. 1989, 22, 66–70.

- Johansson, A.K.; Norring, C.; Unell, L.; Johansson, A. Eating disorders and oral health: A matched case-control study. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2012, 120, 61.

- Philipp, E.; Willershausen-Zönnchen, B.; Hamm, G.; Pirke, K.M. Oral and dental characteristics in bulimic and anorectic patients. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1991, 10, 423–431.

- Pallier, A.; Karimovaa, A.; Boillota, A.; Colon, P.; Ringuenete, D.; Bouchard, P. Dental and periodontal health in adults with eating disorders: A case-control study. J. Dent. 2019, 84, 55–59.

- Touyz, S.; Liew, V.; Tseng, P.; Frisken, K.; Williams, H.; Beumont, P. Oral and Dental Complications in Dieting Disorders. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1993, 14, 341–347.

- Kisely, S.; Baghaie, H.; Lalloo, R.; Johnson, N. Association between poor oral health and eating disorders: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Br. J. Psychiatry 2015, 207, 299–305.

- Chapple, I.L.; Bouchard, P.; Cagetti, M.G.; Campus, G.; Carra, M.C.; Cocco, F.; Nibali, L.; Hujoel, P.; Laine, M.l.; Lingstrom, P.; et al. Interaction of lifestyle, behaviour or systemic diseases with dental caries and periodontal diseases: Consensus report of group 2 of the joint EFP/ORCA workshop on the boundaries between caries and periodontal diseases. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2017, 44, 39–51.

- Chapple, I.L.; Mealey, B.L.; Van Dyke, T.E.; Bartold, P.M.; Dommisch, H.; Eickholz, P.; Geisinger, M.L.; Genco, R.J.; Glogauer, M.; Goldstein, M.; et al. Periodontal health and gingival diseases and conditions on an intact and a reduced periodontium: Consensus report of workgroup 1 of the 2017 World Workshop on the Classification of Periodontal and Peri-Implant Diseases and Conditions. J. Clin. Periodontol. 2018, 45, 68–77.

- Garrido-Martínez, P.; Domínguez-Gordillo, A.; Cerero-Lapiedra, R.; Burgueño-García, M.; Martínez-Ramírez, M.J.; Gómez-Candela, C.; Cebrián-Carretero, J.L.; Esparza-Gómez, G.G. Oral and dental health status in patients with eating disorders in Madrid, Spain. Med. Oral Patol. Oral Cir. Bucal. 2019, 24, 595–602.

- Lourenço, M.; Azevedo, A.; Brandão, I.; Gomes, P. Orofacial manifestations in outpatients with anorexia nervosa and bulimia nervosa focusing on the vomiting behaviour. Clin. Oral Investig. 2018, 22, 1915–1922.

- Loe, H.; Silness, J. Periodontal Disease in Pregnancy. I. Prevalence and Severity. Acta Odontol. Scand. 1963, 21, 533–551.

- Cutress, T.W.; Ainamo, J.; Sardo-Infirri, J. The community periodontal index of treatment needs (CPITN) procedure for population groups and individuals. Int. Dent. J. 1987, 37, 222–333.

- Chiba, F.Y.; Sumida, D.H.; Moimaz, S.A.S.; Chaves Neto, A.H.; Nakamune, A.; Garbin, A.J.I.; Garbin, C.A.S. Periodontal condition, changes in salivary biochemical parameters, and oral health-related quality of life in patients with anorexia and bulimia nervosa. J. Periodontol. 2019, 90, 1423–1430.

- Cortellini, P.; Bissada, N.F. Mucogingival conditions in the natural dentition: Narrative review, case definitions, and diagnostic considerations. J. Periodontol. 2018, 45, 190–198.

- Range, H.; Colon, P.; Godart, N.; Kapila, Y.; Bouchard, P. Eating disorders through the periodontal lens. Periodontol. 2000 2021, 87, 17–31.

- Stanislav, N.; Tolkachjov, M.D.; Bruce, A.J. Oral manifestations of nutritional disorders. Clin. Dermatol. 2017, 35, 441–452.

- Panico, R.; Piemonte, E.; Lazos, J.; Gilligan, G.; Zampini, A.; Lanfranchi, H. Oral mucosal lesions in Anorexia Nervosa, Bulimia Nervosa and EDNOS. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2018, 96, 178–182.

- Lesar, T.; Vidović Juras, D.; Tomić, M.; Čimić, S.; Kraljević Šimunković, S. Oral Changes in Pediatric Patients with Eating Disorders. Acta Clin. Croat. 2022, 61, 185–192.

- Mascitti, M.; Coccia, E.; Vignini, A.; Aquilanti, L.; Santarelli, A.; Salvolini, E.; Sabbatinelli, J.; Mazzanti, L.; Procaccini, M.; Rappelli, G. Anorexia, Oral Health and Antioxidant Salivary System: A Clinical Study on Adult Female Subjects. Dent. J. 2019, 7, 60.

- Paszyńska, E.; Słopień, A.; Slebioda, Z.S.; Dyszkiewicz-Konwińska, M.; Monika Weglarz, M.; Rajewski, A. Macroscopic evaluation of the oral mucosa and analysis of salivary pH in patients with anorexia nervosa. Psychiatr. Pol. 2014, 48, 453–464.

- Back-Brito, G.N.; da Mota, A.J.; de Souza Bernardes, L.Â.; Takamune, S.S.; Prado Ede, F.; Cordás, T.A.; Balducci, I.; da Nobrega, F.G.; Koga-Ito, C.Y. Effects of eating disorders on oral fungal diversity. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. 2012, 113, 512–517.

- Hedman, A.; Breithaupt, L.; Hübel, C.; Thornton, L.M.; Tillander, A.; Norring, C.; Birgegård, A.; Larsson, H.; Ludvigsson, J.F.; Sävendahl, L.; et al. Bidirectional relationship between eating disorders and autoimmune diseases. J. Child Psychol. Psychiatry 2019, 60, 803–812.

- Yadav, K.; Prakash, S. Dental Caries: A review. Asian J. Biomed. Pharm. Sci. 2016, 6, 1–7.

- Moynihan, P.; Petersen, P.E. Diet, nutrition and the prevention of dental diseases. Public Health Nutr. 2004, 7, 201–226.

- Johansson, A.K.; Norring, C.; Unell, L.; Johansson, A. Diet and behavioral habits related to oral health in eating disorder patients: A matched case-control study. J. Eat. Disord. 2020, 8, 7.

- Jung, E.H.; Jun, M.K. Relationship between risk factors related to eating disorders and subjective health and oral health. Children 2022, 9, 786.

- Sheetal, A.; Hiremath, V.K.; Patil, A.G.; Sajjansetty, S.; Kumar, S.R. Malnutrition and its oral outcome—A review. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2013, 7, 178–180.

- Johansson, A.K.; Norring, C.; Unell, L.; Johansson, A. Eating disorders and biochemical composition of saliva: A retrospective matched case–control study. Eur. J. Oral Sci. 2015, 123, 158–164.

- Paszynska, E.; Schlueter, N.; Slopien, A.; Dmitrzak-Weglarz, M.; Dyszkiewicz-Konwinska, M.; Hannig, C. Salivary enzyme activity in anorexic persons-a controlled clinical trial. Clin. Oral Investig. 2015, 19, 1981–1989.

- Dynesen, A.W.; Bardow, A.; Petersson, B.; Nielsen, L.R.; Nauntofte, B. Salivary changes and dental erosion in bulimia nervosa. Oral Surg. Oral Med. Oral Pathol. Oral Radiol. Endodontology 2008, 106, 696–707.

- Ximenes, R.; Couto, G.; Sougey, E. Eating disorders in adolescents and their repercussions in oral health. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2010, 43, 59–64.

- Paszynska, E.; Hernik, A.; Slopien, A.; Roszak, M.; Jowik, K.; Dmitrzak-Weglarz, M.; Tyszkiewicz-Nwafor, M. Risk of dental caries and erosive tooth wear in 117 children and adolescents anorexia nervosa population-a case-control study. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 874263.

- Szupiany-Janeczek, T.; Rutkowski, K.; Pytko-Polończyk, J. Oral cavity clinical evaluation in psychiatric patients with eating disorders: A case-control study. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 4792.

- Manevski, J.; Stojšin, I.; Vukoje, K.; Janković, O. Dental aspects of purging bulimia. Vojnosanit. Pregl. 2020, 77, 300–307.

- Shaughnessy, B.F.; Feldman, H.A.; Cleveland, R.; Sonis, A.; Brown, J.N.; Gordon, C.M. Oral health and bone density in adolescents and young women with anorexia nervosa. J. Clin. Pediatr. Dent. 2008, 33, 87–92.

- Hermont, A.P.; Pordeus, I.A.; Paiva, S.M.; Abreu, M.H.; Auad, S.M. Eating disorder risk behavior and dental implications among adolescents. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 2013, 46, 677–683.

- Brandt, L.M.T.; Freitas Fernandes, L.H.; Silva Aragão, A.; Costa Aguiar, Y.P.; Auad, S.M.; Dias de Castro, R.; D’Ávila Lins Bezerra, B.; Leite Cavalcanti, A. Relationship between risk behavior for eating disorders and dental caries and dental erosion. Sci. World J. 2017, 2017, 1656417.

- Jugale, P.V.; Pramila, M.; Murthy, A.K.; Rangath, S. Oral manifestations of suspected eating disorders among women of 20–25 years in Bangalore City, India. J. Health Popul. Nutr. 2014, 32, 46–50.

- De Moor, R.J.G. Eating disorder-induced dental complications: A case report. J. Oral Rehabil. 2004, 31, 725–732.

- Amaechi, B.T.; Higham, S.M. Dental erosion: Possible approaches to prevention and control. J. Dent. 2005, 33, 243–252.

- The Erosive Tooth Wear Foundation. What Is Erosive Toothwear? Available online: www.erosivetoothwear.com (accessed on 13 August 2023).

- Schebendach, J.E.; Mayer, L.E.; Devlin, M.J.; Attia, E.; Contento, I.R.; Wolf, R.L.; Walsh, B.T. Dietary energy density and diet variety as predictors of outcome in anorexia nervosa. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 87, 810–816, Erratum in Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2012, 96, 222.

- Raatz, S.K.; Jahns, L.; Johnson, L.K.; Crosby, R.; Mitchell, J.E.; Crow, S.; Peterson, C.; Le Grange, D.; Wonderlich, S.A. Nutritional adequacy of dietary intake in women with anorexia nervosa. Nutrients 2015, 15, 3652–3665.

- Monteiro, C.A.; Cannon, G.; Lawrence, M.; Costa Louzada, M.; Pereira Machado, P. Ultra-Processed Foods, Diet Quality, and Health Using the NOVA Classification System; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations: Rome, Italy, 2019.

- Schlueter, N.; Luka, B. Risk groups. Br. Dent. J. 2018, 224, 364–370.

- Schlueter, N.; Tveit, A.B. Prevalence of erosive tooth wear in risk groups. Monogr. Oral Sci. 2014, 25, 74–98.

More

Information

Subjects:

Dentistry, Oral Surgery & Medicine

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

577

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

06 Nov 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No