Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ran Gao | -- | 1461 | 2023-10-16 10:35:01 | | | |

| 2 | Catherine Yang | Meta information modification | 1461 | 2023-10-16 10:45:38 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Gao, R.; Chen, Q.; Li, Y.; Huang, H. Emeralds from Kagem Mine, Kafubu Area, Zambia. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/50335 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Gao R, Chen Q, Li Y, Huang H. Emeralds from Kagem Mine, Kafubu Area, Zambia. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/50335. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Gao, Ran, Quanli Chen, Yan Li, Huizhen Huang. "Emeralds from Kagem Mine, Kafubu Area, Zambia" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/50335 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Gao, R., Chen, Q., Li, Y., & Huang, H. (2023, October 16). Emeralds from Kagem Mine, Kafubu Area, Zambia. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/50335

Gao, Ran, et al. "Emeralds from Kagem Mine, Kafubu Area, Zambia." Encyclopedia. Web. 16 October, 2023.

Copy Citation

Kagem emerald mine in Zambia is deemed the largest open-pit emerald mine in the world, with extremely high economic value and a large market share. Mineral inclusions typically include actinolite, graphite, magnetite, and dolomite. Black graphite encased in actinolite in Kagem emeralds is reported herein for the first time. The FTIR spectrum of Kagem emeralds reveals that the absorption of type II H2O is stronger than that of type I H2O, indicating the presence of abundant alkali metals, which was confirmed through chemical analysis. Kagem emeralds contain high levels of Na (avg. 16,440 ppm), moderate-to-high Cs (avg. 567 ppm), as well as low-to-moderate K (avg. 185 ppm) and Rb (avg. 14 ppm) concentrations.

emerald

Kagem mine

gemological characteristics

origin traceability

1. Introduction

Emerald is the green variety of beryl colored by chromium and vanadium, and its ideal chemical formula is Be3Al2SiO18. The traditional classification system for emerald deposits has been expanded upon by Giuliani et al. (2019) [1]. Emerald occurrences and deposits were reclassified into two main types: tectonic magmatic-related (Type I) and tectonic metamorphic-related (Type II), and further subdivided into seven sub-types based on host rock types. The Kafubu deposit in Zambia was classified as Type IA, associated with mafic-ultramafic rocks.

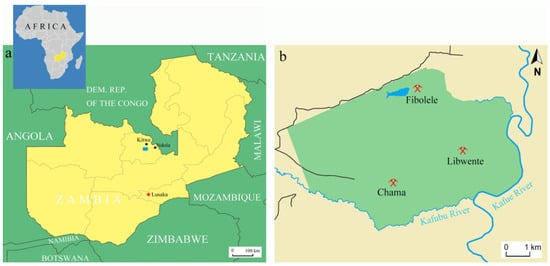

Zambia is one of the most significant emerald sources worldwide, second only to Colombia. Kagem emerald mine is located in the Ndola Rural Emerald Restricted Area and lies south of Kitwe and west of Ndola, in Zambia’s Copperbelt Province (Figure 1). Kagem mine is considered the world’s largest single open-pit emerald mine, accounting for approximately 25%–30% of global emerald production, with a potential mine life of 22 to 2044 years [2]. Besides the Kagem mine, there are other larger mines in the Kafubu area, including Kamakanga, Grizzly, and Chantete [3][4].

Figure 1. (a) Zambia is a landlocked country located in the southern part of Africa; the capital is Lusaka. The Kagem mine (blue rectangle) is located in north-central Zambia, near the Kafubu River in the Ndola Rural Emerald Restricted Area (NRERA); (b) There are three operating pits in the Kagem mine: Chama, Libwente, and Fibolele. Picture: Ran Gao.

Bank (1974) [5] proposed that the necessary chromic element in emeralds, chromium, comes from the magnetite in talc–magnetite schist. Koivula (1982) [6] was the first to report on the presence of tourmaline in Zambian emeralds. Sliwa and Nguluwe (1984) [7] described the geological setting of Zambian emeralds. Seifert et al. (2004a) [8] first provided quantitative geochemical, petrological, and mineralogical data on the major rock types of the Kafubu emerald deposits. Seifert et al. (2004b) [9] conducted a comprehensive study of the environmental impact of the emerald mines in the Kafubu area. Zwaan et al. (2005) [3] first reported the Musakashi area, a new emerald deposit initially worked by local miners in 2002 [10]. In 2014, GIA Lab conducted a field exploration of the history, region geology, mining methodology, processing, operation, and auction of the Kagem mine, and published a detailed report [11]. However, detailed studies on the spectroscopy and chemical composition of Kagem emeralds still need to be completed [12].

2. Geological Setting

The Kagem emerald concession covers an area of approximately 46 square kilometers within a 200-square-kilometer productive zone, and comprises the current operating Chama open pit mine and the bulk sampling pits at Libwente and Fibolelem [3].

The Kafubu area is located geologically at the center of the transcontinental Pan-African belts in central-southern Africa. The Crustal evolution is thought to be related to three successive orogenic events: the Ubendian, Irumide, and Lufilian (Pan-African) [13][14][15]. The Kafubu emerald deposits occur within metamorphic rocks of the Muva Supergroup that date back to around 1700 Ma [million years ago] [16][17]. The Muva Supergroup overlays the basement granite gneisses, consisting of footwall mica schist, talc–magnetite schist, amphibolite, and quartz–mica schist from bottom to top. The entire crustal domain subsequently underwent folding, thrusting, and metamorphism during the Pan-African orogeny, peaking at 530 Ma [18].

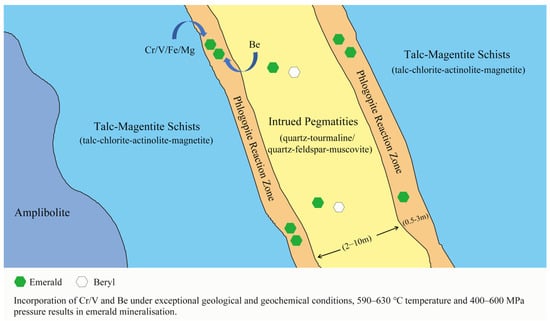

Emerald mineralization in the Kagem mine is hosted by the talc–magnetite schist, which contains talc–chlorite–actinolite–magnetite schists (Figure 2) [7][14]. These schists were identified as metamorphosed komatiites—Mg-rich ultramafic rocks [9]. During the late stages of the Pan-African orogeny, the talc–magnetite schist was intruded by beryllium-rich pegmatite dykes (typically 2–10 m thick) [19][20]. These pegmatites appear as feldspar–quartz–muscovite bodies or as minor quartz–tourmaline veins, and are believed to be related to neighboring granitic rocks [7]. The steeply inclined pegmatite dykes and quartz tourmaline veins typically trend north to south or northwest to southeast.

The emerald mineralization in the Kagem mine results from the interaction between metabasites and pegmatites and their accompanying hydrothermal fluids [9][19]. Emeralds are found in the phlogopite reaction zone (typically 0.5–3 m wide) between the talc–magnetite schist and the pegmatites, and in the quartz–tourmaline veins, which produces gem-quantity emeralds, but only a tiny percentage [3]. In the reaction zone, talc–magnetite schist provides the important chromophore of chromium, while the pegmatites provided the beryllium. Emeralds were formed under the proper pressure, temperature conditions (400–600 MPa and 590–630 °C), and chemical environment, around 500 Ma [9][21]. The area subsequently underwent intense shearing and folding during the Lufilian orogeny, which may account for the fracturing and opacity of many emerald crystals [7].

Figure 2. Schematic representation of the metasomatic reaction zone between the talc–magnetite schists, and the pegmatite-formed common beryl and gem-quality emeralds. Modified from [22].

3. History

There are two major emerald areas in Zambia: the Musakashi and Kafubu areas. The Musakashi area was first reported in 2005. The emeralds from this area were characterized by their intense bluish-green color and multiphase inclusions, which were similar to the emeralds found in Muzo, Colombia [3][10][23]. Beryl was first discovered in the Kafubu area in 1928 by two geologists named Dicks and Baker. Some small exploration works were carried out during the 1940s and 50s [7]. Zambia’s Geological Survey Department mapped the Miku area and verified the deposit in 1971 [13][14]. After new occurrences were discovered in the 1970s, the Kafubu area became a significant producer of high-quality emeralds. Because of the dramatic expansion of production and extensive illegal mining, the Government relocated the local population and established a restricted zone called the Ndola Rural Emerald Restricted Area [9]. In 1980, Kagem Mining Ltd. (55% owned by the Zambian Government) was authorized to explore and mine the Kafubu area in the same year [9].

In 2004, the British public-listed Gemfields Resources PLC began systematic exploration near the Pirala mine, south of the Ndola River, and discovered significant emerald deposits. Gemfields was awarded a management contract there in 2007. In the following year, Gemfields acquired 75% ownership of the mine, the remainder being held by the Government [11].

Kagem is primarily an open-pit mine, which presents the advantage of providing accessibility to every carat of emerald (Figure 3). After the surrounding rock is removed, miners utilize hammers and chisels to recover the emeralds. Any extracted production goes into a red production box (Figure 4). Since 2010, the Kagem mine has been responsible for approximately 50% of emerald production in Zambia. Despite the high production volume, only a small portion of gem-quality emeralds are available for exportation. In 2022, the Kagem mine produced a total of 37.2 million carats of emeralds and beryl, including 259,500 carats of premium emeralds [24].

Figure 3. The Kagem mine is the world’s largest open-pit mine for emeralds and is located in the Ndola Rural District, Copperbelt Province, Zambia. Photo by Xiangjie Xiao.

Figure 4. (a) Miners use hammers and chisels to extract emeralds from the rock in the reaction zone; (b) The collected emeralds in a secure box. Photo by Xiangjie Xiao.

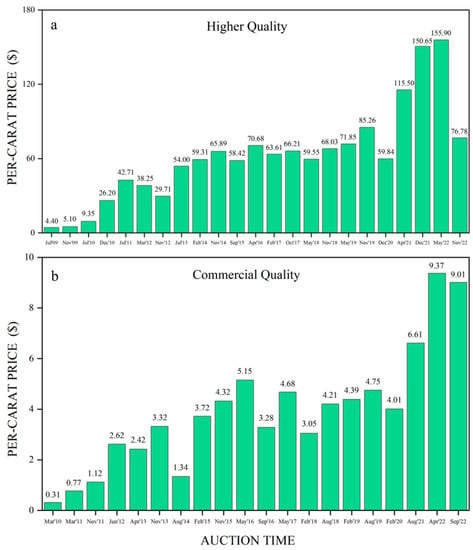

Colored gemstone auctions have become a major source of revenue for the Gemfields Group. The company established its proprietary grading system to assess each gem according to its individual characteristics (size, color, shape and clarity) and implemented a pioneering auction and trading platform. The auctions were divided into two quality ranges: one for higher-quality (HQ) emeralds and one for commercial-quality (CQ, formerly known as lower-quality before 2016) emeralds [2]. The auctions are held in multiple cities, including Jaipur, Johannesburg, Lusaka, London, Dubai, and Singapore [24]. Gemfields had held 43 auctions of emerald and beryl mined at Kagem up to November 2022, and generated $899 million in aggregate revenues [24]. The per carat price for HQ and CQ emeralds in 43 auctions has been recorded (Figure 5a,b). The specific auction mix and the quality of the lots offered at each auction vary in characteristics such as size, color and clarity due to changes in mined production and market demand. Overall, the price of emeralds has shown a clear upward trend, with HQ emeralds increasing from an initial $4.40 per carat (July 2009) to a peak of $155.90 (May 2022) per carat and CQ emeralds rising from an initial $0.31 per carat (January 2010) to a highest $9.37 per carat (April 2022). The value of and demand for emeralds are rising steadily.

Figure 5. (a) The per carat price (calculated as: received/total weight sold) for higher quality emeralds from the Kagem mine at auctions, tracked since July 2009; (b) The per carat price for commercial quality emeralds from the Kagem mine at auctions, recorded since March 2010. Auction data from [24].

References

- Giuliani, G.; Groat, L.A.; Marshall, D.; Fallick, A.E.; Branquet, Y. Emerald Deposits: A Review and Enhanced Classification. Minerals 2019, 9, 105.

- Gemfields Group Limited 2022. Interim Report 2022. Available online: https://senspdf.jse.co.za/documents/2022/jse/isse/GMLE/Interim22.pdf (accessed on 13 September 2022).

- Zwaan, J.C.; Seifert, A.; Vrána, S.; Laurs, B.; Anckar, B.; Simmons, W.; Falster, A.; Lustenhouwer, W.; Koivula, J.; Garcia-Guillerminet, H. Emeralds from the Kafubu Area, Zambia. Gems Gemol. 2005, 41, 116–148.

- Zhang, Y.; Yu, X.-Y. Inclusions and Gemological Characteristics of Emeralds from Kamakanga, Zambia. Minerals 2023, 13, 341.

- Bank, H. The emerald occurrence of Miku, Zambia. J. Gemmol. 1974, 14, 8–15.

- Koivula, J. Tourmaline as an Inclusion in Zambian Emeralds. Gems Gemol. 1982, 18, 225–227.

- Sliwa, A.S.; Nguluwe, C.A. Geological setting of Zambian emerald deposits. Precambrian Res. 1984, 25, 213–228.

- Seifert, A.; Vrána, S.; Lombe, D.K.; Mwale, M. Impact Assessment of Mining of Beryl Mineralization on the Environment in the Kafubu Area; Problems and Solutions. Geol. Surv. Czech Rep. 2004, 1, 63.

- Seifert, A.; Žáček, V.; Vrána, S.; Pecina, V.; Zacharias, J.; Zwaan, J.C. Emerald mineralization in the Kafubu area, Zambia. Bull. Geosci. 2004, 79, 1–40.

- Saeseaw, S.; Pardieu, V.; Sangsawong, S. Three-Phase Inclusions in Emerald and Their Impact on Origin Determination. Gems Gemol. 2014, 50, 114–132.

- Hsu, T.; Lucas, A.; Pardieu, V.; Gessner, R. A Visit to the Kagem Open-pit Emerald Mine in Zambia. Gems Gemol. Available online: http://www.gia.edu/gia-news-research-kagem-emerald-mine-zambia (accessed on 22 July 2022).

- Behling, S.; Wilson, W.E. The kagem emerald mine: Kafubu area, Zambia. Mineral. Rec. 2010, 41, 59–67.

- Hickman, A.C.J. The Miku emerald deposit. Geol. Surv. Zambia Econ. Rep. 1972, 27, 35.

- Hickman, A.C.J. The Geology of the Luanshya Area. Geol. Surv. Zambia Rep. 1973, 46, 32.

- Tembo, F.; Kambani, S.; Katongo, C.; Simasiku, S. Draft Report on the Geological and Structural Control of Emerald Mineralization in the Ndola Rural Area, Zambia; University of Zambia, School of Mines: Lusaka, Zambia, 2000; p. 72.

- Daly, M.; Unrug, R. The Muva Supergroup of Northern Zambia: A craton to mobile belt sedimentary sequence. Trans. Geol. Soc. S. Afr. 1982, 85, 155–165.

- Waele, B.D.; Wingate, M.T.D.; Mapani, B.; Fitzsimons, I. Untying the Kibaran knot: A reassessment of Mesoproterozoic correlations in southern Africa based on SHRIMP U-Pb data from the Irumide belt. Geology 2003, 31, 509–512.

- John, T.; Schenk, V.; Mezger, K.; Tembo, F. Timing and PT Evolution of Whiteschist Metamorphism in the Lufilian Arc-Zambezi Belt Orogen (Zambia): Implications for the Assembly of Gondwana. J. Geol. 2004, 112, 71–90.

- Cosi, M.; Debonis, A.; Gosso, G.; Hunziker, J.; Martinotti, G.; Moratto, S.; Robert, J.P.; Ruhlman, F. Late proterozoic thrust tectonics, high-pressure metamorphism and uranium mineralization in the Domes Area, Lufilian Arc, Northwestern Zambia. Precambrian Res. 1992, 58, 215–240.

- Parkin, J. Geology of the St. Francis Mission and Musakashi River Areas. Explanation of Degree Sheet 1226 NE and SE Quarters and Part of 1126 SE Quarter. Geol. Surv. Zambia Rep. 2000, 80, 49.

- Holland, T.; Blundy, J. Non-ideal interactions in calcic amphiboles and their bearing on amphibole-plagioclase thermometry. Contrib. Mineral. Petrol. 1994, 116, 433–447.

- Gemfields Group Limited 2015. A Competent Persons Report on the Kagem Emerald Mine, Zambia. Available online: https://www.gemfieldsgroup.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/08/U6512_Kagem_Report_v14R.pdf (accessed on 22 September 2022).

- Pardieu, V.; Detroyat, S.; Sangsawong, S.; Saeseaw, S. In Search of Emeralds from the Musakashi Area of Zambia. InColor 2015, 6–12.

- Gemfields Group Limited 2023. Operational Market Update For the year ended 31 December 2022. Available online: https://www.gemfieldsgroup.com/operational-market-update-31-december-2022/?upf=dl&id=13426 (accessed on 12 February 2023).

More

Information

Subjects:

Others

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

2.0K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

16 Oct 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No