Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Hamed Tavakoli | -- | 2242 | 2023-10-16 08:26:40 | | | |

| 2 | Hamed Tavakoli | Meta information modification | 2242 | 2023-10-17 00:50:26 | | | | |

| 3 | Sirius Huang | Meta information modification | 2242 | 2023-10-19 02:40:08 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Tavakoli, H.; Hedayati Marzbali, M.; Maghsoodi Tilaki, M.J. Liminality as a Theoretical Tool in Historic Cities. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/50328 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Tavakoli H, Hedayati Marzbali M, Maghsoodi Tilaki MJ. Liminality as a Theoretical Tool in Historic Cities. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/50328. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Tavakoli, Hamed, Massoomeh Hedayati Marzbali, Mohammad Javad Maghsoodi Tilaki. "Liminality as a Theoretical Tool in Historic Cities" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/50328 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Tavakoli, H., Hedayati Marzbali, M., & Maghsoodi Tilaki, M.J. (2023, October 16). Liminality as a Theoretical Tool in Historic Cities. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/50328

Tavakoli, Hamed, et al. "Liminality as a Theoretical Tool in Historic Cities." Encyclopedia. Web. 16 October, 2023.

Copy Citation

The methods of urban revitalisation in historic cities may include several approaches, from mere preservation to physical intervention or a combination of both. Since Middle Eastern historic cities exist as a transitional phenomenon, spatial liminality is identified as an epistemological tool for their investigation.

dilapidated abandoned buildings (DABs)

spatial liminality

territorial interdependence

revitalization

historic city

1. Theoretical Backgrounds: Socio-Spatial Revitalisation of Historic Cities

Since the 18th century, several global schools of thought have reiterated a need for the revitalisation of heritage sites and cultural properties [1]. The methods of urban revitalisation in historic cities may include several approaches, from mere preservation to physical intervention or a combination of both [2]. Cultural heritage values should direct levels of intervention for the revitalisation of historic cities, and any intervention that would lessen or compromise such values is objectionable and should not occur [3]. It is crucial to understand that the preservation of cultural heritage sites and objects is underpinned by values projected by the public onto essentially inanimate objects that are not static but possess mutable qualities on an intergenerational scale [4].

Since the 1970s, historic cities in the Middle East have undergone a reassessment of their importance [5]. In the 21st century, historic revitalisation is largely associated with city planning and development. Advocates promote preservation as a key driver of urban revitalisation; however, there is a shortage of empirical research that addresses this connection, especially in an Iranian setting [5]. In this respect, the progressive development of regeneration programs created awareness of the impossibility of separating historic centres (either in analytical or in planning terms) from their municipal, territorial, and social contexts, which are linked by mutual, deep relationships [4]. Nonetheless, today, identity generation and empowerment of local communities have become an indispensable part of any regeneration program, especially in the case of old city centres or other historic environments at risk of abandonment [6].

2. Liminality as a Theoretical Tool in Historic Cities

In the 20th century, the radical transformation of historic Middle Eastern cities was a consequence of social-spatial changes driven by the industrial age, despite the fact that changes in such architectural fabrics in previous centuries had occurred naturally and organically [7]. Such socio-spatial disruptions generated an ever-widening chasm between past and future, pulled the present of historic cities apart, and emptied it of many of its essential qualities. Therefore, historic areas in Middle Eastern cities can be viewed as entities suspended between the premodern and contemporary epochs [8], neither entirely losing their traditional properties (e.g., unique structures/land grains/narrow roads), nor capable of adapting themselves to the surrounding modern built environment. Liminality can thus draw new insights into understanding spatial and temporal transitions between heritage fabrics and spaces of everyday life [9][10]. As a result, liminality is a suitable tool for understanding socio-spatial vulnerability in the context of urban regeneration in historic Iranian/Middle Eastern cities, whereby dilapidated abandoned buildings (DABs) can meaningfully reflect the liminal qualities of life. Here, a gap in the relevant scholarship is the relationship between the extent of DABs and the formation of socio-spatial vulnerability, which can be examined using spatial liminality [10].

In anthropology, liminality is used as a measure for understanding the vulnerability of individuals or social groups, living in limbo, among (and in interaction with) other human beings [11]. Arnold Van Gennep [12] first coined liminality, upon which he distinguished rites that mark the passage of an individual or social group from one status to another. Following van Gennep, by coining spatial liminality, Thomassen [13] indicated the third dimension of liminality as place, moving beyond the dichotomy of time and event as the foundations of liminality. Thomassen noted van Gennep’s specification that liminality is essentially a spatial concept, demonstrating that, perhaps, the physical passage of a threshold somehow preceded the rites that demarcate a symbolic or spiritual passage.

By elaborating on “spatial liminality”, Thomassen advanced Karl Jaspers’ theory of the Axial Age, demonstrating that there are substantial grounds to believe that Jaspers’ theory could be comprehended using liminality [13], suggesting that in-between spatial positioning could be the primary cause for the simultaneous generation of rites of transition among neighbouring societies.

In a similar context, Stavrides proposed that in-betweenness can be activated by unblocking the paralyzed potential of a threshold space [14]. He further described how a threshold space can generate socio-spatial conditions in which people undergo the transition from one social identity to another, and suggested that societies explicitly control these transitional periods by regulating rites of passage to ensure that liminal people pass to a different social status without threatening social reproduction [14]. Stavrides believes that such threshold spaces could be marked by experiences of social liminality in which in-between spaces do not merely circumscribe a defined area of use, but instead offer a passage from one social status to another [15].

Thus, in-between places are spaces with the power to institute comparisons and encourage new relations/communications between different people. Here, a threshold space connects and separates individuals at the same time [16]. Thus, thresholds as prearranged structures enable societies to symbolically construct their experience of negotiation and simultaneously facilitate the creation of material artefacts, that allow negotiations and generational changes to take place [14].

Threshold spaces can thus offer areas for conciliation and encounters with otherness, which may be created between permeable and evolving identities. In this sense, distinctive cultures can infuse/diffuse across borders and among adjacent interdependent communities [17]. Consequently, porous in-between spaces can arguably be seen to be specifically relevant to the formation of spatial liminality by generating socio-spatial interdependence, that in the past brought meaning to space in Middle Eastern medieval cities/neighbourhoods, and thus be productive of place formation [9].

3. The Formation of Liminal Middle Eastern States

In contrast to the condition of modern territorial states, territorialities of medieval states in the Middle East can be clearly described by spatial liminality, characterised by osmotic borders and territorial interdependence that together facilitate rites of passage amongst neighbouring states. In addition, rites of passage here do not involve the physical crossing of borders, but instead, signify real-life transitions. Consequently, it appears that in a Middle Eastern historic city, liminality operates at various scales, including the civic and communal levels (e.g., within religious groups and subgroups) as well as the national and transnational contexts [9].

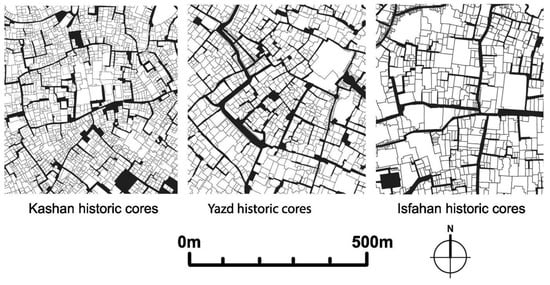

Generally, in Middle Eastern historic cities, the social interconnections between heterogeneous communities were established by private, blind alleys, or semi-private spaces, such as lanes. Cul-de-sacs were regarded strictly as an extension of the household’s private space and could be a place for social interaction between local women and children [18]. As citizens moved from blind alleys to lanes, social relations increased from extended families (or several related families) in blind alleys to more diverse families in semi-private lanes (Figure 1). As residents bypassed these lanes and passages, they became concentrated in small squares that caused even more collisions and formed subsequent social relations amongst diverse neighbourhoods [19].

Figure 1. The cul-de-sac worked as a semi-private space in historic Iranian cities, while tiny squares provided access to dwellings and generated social groupings. Maps show the somehow untouched condition of these cities in 2018 [9].

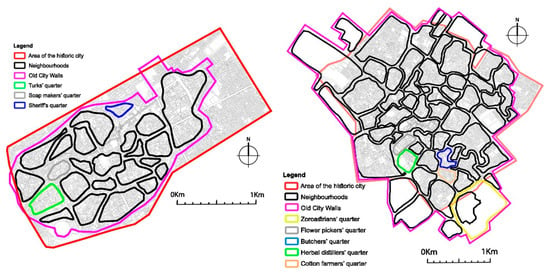

Therefore, public and semi-public roads could accommodate interneighbourhood interactions, thanks to adjacent shops, mosques, caravanserai, schools, and other public spaces, which made such small communities/neighbourhoods interdependent [20]. As a result, most urban traffic used major thoroughfares, roads, and in-between spaces to link important areas for commercial or religious purposes, while neighbourhoods were accessible only by immediate cohorts in a distinct community (Figure 2) [21]. Consequently, diverse communities could establish intergroup negotiations and have access to communal spaces, namely public squares, neighbourhood centres, bazaars, mosques, and schools, using connecting roads [18].

Figure 2. Heterogeneous neighbourhoods in the medieval city of Yazd (right) and Kashan (left) were formed as a result of the accumulation of people with mutual religious identities or similar types of occupations in one place [22].

From a road network system perspective, in historic cities, three types of roads are identifiable: firstly, public roads that connected major neighbourhoods and could be extended as traditional bazaars or stretched to a city gate; secondly, semi-public roads that interconnected public roads and facilitated access to neighbourhoods, including local shops, which also served as a neighbourhood centre for social interaction, a playground for children, and/or a stage for jugglers or street vendors; and thirdly, dead-end alleyways, or semi-private roads branched out from semi-public roads, that provided access to a cluster of private houses [23]. Not unlike roads, the territorial implication of open spaces in historic cities is apparent in the functionality of in-between spaces (e.g., courtyards) and across scales, containing private, semi-private, and public areas in historic cities [24]. In a historic Middle Eastern city, courtyards facilitated multipurpose spaces for communal relations, group games, social entertainment, religious rituals, commercial activities and trades, ceremonial events, and inter-neighbourhood collaborations/negotiations. A courtyard could have facilitated socio-ethical arrangements for extended families (or smaller social groups) to live mutually around a semi-private threshold space. Here, in-between spaces tend to generate complex borders among neighbourhoods, while in most cases, these boundaries are not accurate [22]. Within a traditional neighbourhood, small courtyards in cul-de-sacs functioned as semi-private spaces, used by all the inhabitants of surrounding dwellings for social and recreational activities. These tiny squares, surrounded by and providing access to dwellings/buildings in old cities, generated social values by enhancing socio-spatial associations between residents (Figure 3) [18].

Figure 3. Hierarchical in-between spaces and the formation of spatial liminality in historic Kashan [22].

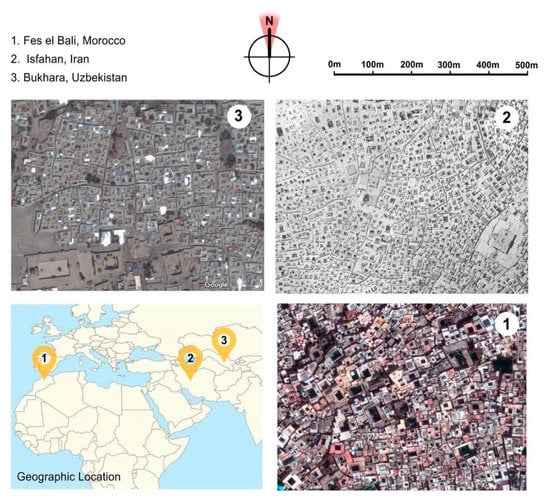

Therefore, those hierarchical divisions arguably reflect that in-between spaces somehow facilitated spatial liminality inside neighbourhoods within historic cities during the medieval era and became porous membranes that led to the facilitation of the rites of passage among social groups (Figure 4) [22].

Figure 4. The morphology of courtyard structures in Middle Eastern and North African cities [22].

4. Social Aspects of Spatial Liminality

Spatial aspects of liminality as a substructure for social interaction involve widespread social ramifications that emerge once people cross a threshold [25]. In this respect, social aspects of liminality in historic cities had been relevant to the formation of sense of place, engendered by socio-spatial exchanges, that may occur within in-between spaces.

The design of those cities thus reinforced the sense of citizenship by implementing special zoning practices, including building semi-private quarters or blocks allocated to cohorts according to their ethnic/citizenship origin. Accordingly, such neighbourhood zoning became socially ideal, as each social group was accustomed to maintaining strong ties between its members, preferring to live in a territory close to each other. However, the implication of such communitarian design practices, e.g., neighbourhood zoning (that generated the territoriality of social groups), and the consequent intergroup negotiations/relations (via in-between spaces) fostered multiple communities in historic cities to live together, which culminated in medieval diversity [26].

Based on the above discussion on liminality, it could be assumed that rites of passage (generated via spatial liminality) for communities, as described by Thomassen [25], had occurred as a consequence of socio-spatial intergroup relationships within threshold spaces, which occurred amongst social groups (made up of individual citizens) separated by spatial territorialities. Here, Thomassen’s [25] discussion regarding in-between spatial positioning, in-between spaces, and the formation of interacting/liminal societies as signifying territorial interdependence, is not dissimilar to what Stavrides [27] described as “heterotopia”, by which he refers to interdependent places that maintain osmotic boundaries/territorialities while generating porous urban spaces, suitable for “acts of encounter” between communities. Stavrides refers to Foucault’s assertion that “heterotopias always presuppose a system of opening and closing that isolates them and makes them penetrable at one and the same time”: those “other places”, therefore, are simultaneously connected to and separated from the places from which they differ [27]. Here, such resemblances between descriptions of the two thinkers of liminality (Thomassen and Stavrides) verify that rites of passage in both cases could represent spatial liminality as specified herein, must have at least five intrinsic qualities: Firstly, within heterotopia, medieval Middle Eastern states/neighbourhoods and centres of the Axial Age, several unique social groups need to coexist. Secondly, individuals within such distinct social groups receive a special membership in terms of being a right-bearing citizen of the community. Thirdly, such heterogeneous communities should be bounded by specific territorialities that make certain places different from other places [28]. Fourthly, for the survival of such social groups, different socio-spatial interactions need to be established. Fifthly, (and most importantly in our discussion) the existence of threshold and osmotic (in-between) spaces becomes necessary for the improvisation of such socio-spatial interactions. Such qualities clearly show the relational status of spatial liminality in heterotopia, medieval Middle Eastern states/cities and identity societies of the Axial Age (Table 1).

Table 1. Five essential elements of spatial liminality.

| Components of Spatial Liminality | Heterotopia | The Axial Age | Middle Eastern States | Neighbourhoods in Middle Eastern Cities |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Citizenship/Membership | Membership of the heterotopia as opposed to the surrounding spaces of normality | Membership of a specific civilization or religion | Membership of a specific state | Membership of a specific neighbourhood/ community |

| Formation of interdependent social/identity groups | Social groups in neighbourhoods | Larger societies, nationalities | Interdependent states | Interdependent neighbourhoods/communities |

| Formation of territoriality | Physical areas inside the boundaries of neighbourhoods | Continents, countries or larger geographic–ethnic regions | Countries and States | Physical areas inside the boundaries of neighbourhoods |

| Formation of socio-spatial interactions | Interneighbourhood relationships (e.g., trades, negotiations, games, etc.) | International discourses, large-scale wars, trades, and religious debates | Interstate discourses, regional wars, trades, and religious debates | Interneighbourhood relationships (e.g., trades, negotiations, games, etc.) |

| In-between/threshold spaces as places of negotiation/interactions | In-between public spaces among neighbourhoods | Thresholds in-between countries (e.g., Mesopotamia) | In between boundary zones | In-between public spaces among neighbourhoods (e.g., roads and courtyards) |

References

- Behzadfar, M. Strategic Plan for Historic Yazd Volume 6-1; Ministry for Roads and Urban Development: Tehran, Iran, 2012.

- Spennemann, D.H. The Shifting Baseline Syndrome and Generational Amnesia in Heritage Studies. Heritage 2022, 5, 2007–2027.

- Australia ICOMOS. Burra Charter: The Australia ICOMOS Charter for Places of Cultural Significance; Autralia ICOMOS: Burwood, Australia, 1999.

- Roberts, P.; Sykes, H.; Granger, R. Urban Regeneration, 2nd ed.; Sage: London, UK, 2016.

- Tavakoli, H.; Marzbali, M.H. Urban Public Policy and the Formation of Dilapidated Abandoned Buildings in Historic Cities: Causes, Impacts and Recommendations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6178.

- Tanrıkul, A.; Hoşkara, Ş. A new framework for the regeneration process of Mediterranean historic city centres. Sustainability 2019, 11, 4483.

- Tavakoli, H. Spatial Liminality as a Framework for Evaluating Revitalisation Programs in Historic Iranian Cities: The Case of the Imam-Ali Project in Isfahan. In Proceedings of the What If? What Next? Speculations on History’s Futures, Perth, Australia, 18–25 November 2020; pp. 261–278.

- Maghsoodi-Tilaki, M.J.; Marzbali, M.H.; Safizadeh, M.; Abdullah, A. Quality of place and resident satisfaction in a historic–religious urban settlement in Iran. J. Place Manag. Dev. 2021, 14, 462–480.

- Tavakoli, H.; Westbrook, N.; Sharifi, E.; Marzbali, M.H. Socio-spatial vulnerability and dilapidated abandoned buildings (Dabs) through the lens of spatial liminality: A case study in Iran. A/Z ITU J. Fac. Archit. 2020, 17, 61–78.

- Roberts, L. Spatial Anthropology: Excursions in Liminal Space; Rowman & Littlefield: London, UK, 2018.

- Szakolczai, A. Liminality and experience: Structuring transitory situations and transformative events. Int. Political Anthropol. 2009, 2, 141–172.

- van Gennep, A. The Rites of Passage: A Classic Study of Cultural Celebrations; University of Chicago: Chicago, IL, USA, 1960.

- Thomassen, B. Revisiting liminality: The danger of empty spaces. In Liminal Landscapes; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 37–51.

- Stavrides, S. Towards the City of Thresholds, Professional Dreamers; Professional Dreamers: Toronto, ON, Canada, 2010.

- Stavrides, S. Open space appropriations and the potentialities of a “City of Thresholds”. In Terrain Vague; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 62–75.

- Simmel, G. The metropolis and mental life. In The Urban Sociology Reader; Routledge: London, UK, 1997; pp. 37–45.

- Foucault, M.; Miskowiec, J. Of other spaces. Diacritics 1986, 16, 22–27.

- Mortada, H. Traditional Islamic Principles of Built Environment; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2003.

- Habib, F.; Moztarzadeh, H.; Hodjati, V. The concept of neighborhood and its constituent elements in the context of traditional neighborhoods in Iran. Adv. Environ. Biol. 2013, 2270–2279.

- Holt, P. The Islamic city. Edited by AH Hourani and SM Stern. J. R. Asiat. Soc. 2011, 104, 147–148.

- Correia, J. Looking beyond the lens’ veil. In Inside/Outside Islamic Art and Architecture: A Cartography of Boundaries in and of the Field; Bloomsbury Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2021; p. 61.

- Tavakoli, H. Dilapidated Abandoned Buildings (DABs) and Socio-Spatial Vulnerability: Application of Spatial Liminality for Revitalising Historic Iranian Cities; The University of Adelaide: Adelaide, Australia, 2020.

- Habibi, K. Behsazi va Nosazi-e Bafthaye-i Kohane-i Shahri ; Nashri Entekhab: Tehran, Iran, 2010.

- Alawadi, K. A return to the old landscape? Balancing physical planning ideals and cultural constraints in Dubai’s residential neighborhoods. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2019, 34, 235–263.

- Thomassen, B. Liminality and the Modern: Living through the In-Between; Routledge: London, UK, 2016.

- Saoud, R. Introduction to the Islamic City. In Discover the Golden Age of Muslim Civilization; Foundation for Science Technology and Civilization: Manchester, UK, 2001; pp. 90–98.

- Stavrides, S. Heterotopias and the experience of porous urban space. In Loose Space; Routledge: London, UK, 2007; pp. 174–192.

- Hosseini, A.; Finn, B.M.; Momeni, A. The complexities of urban informality: A multi-dimensional analysis of residents’ perceptions of life, inequality, and access in an Iranian informal settlement. Cities 2023, 132, 104099.

More

Information

Subjects:

Urban Studies

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.1K

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

19 Oct 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No