Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Domingo C. Salazar-García | -- | 1267 | 2023-10-13 10:19:22 | | | |

| 2 | Lindsay Dong | -41 word(s) | 1226 | 2023-10-15 13:54:47 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Salazar-García, D.C.; García-Borja, P.; Talamo, S.; Richards, M.P. Cova de la Sarsa (València, Spain). Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/50252 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Salazar-García DC, García-Borja P, Talamo S, Richards MP. Cova de la Sarsa (València, Spain). Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/50252. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Salazar-García, Domingo C., Pablo García-Borja, Sahra Talamo, Michael P. Richards. "Cova de la Sarsa (València, Spain)" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/50252 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Salazar-García, D.C., García-Borja, P., Talamo, S., & Richards, M.P. (2023, October 13). Cova de la Sarsa (València, Spain). In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/50252

Salazar-García, Domingo C., et al. "Cova de la Sarsa (València, Spain)." Encyclopedia. Web. 13 October, 2023.

Copy Citation

Cova de la Sarsa (València, Spain) is one of the most important Neolithic impressed ware culture archaeological sites in the Western Mediterranean. It has been widely referenced since it was excavated in the 1920s, due partly to the relatively early excavation and publication of the site, and partly to the qualitative and quantitative importance of its archaeological remains.

Cova de la Sarsa

Early Neolithic

Western Mediterranean

1. Introduction

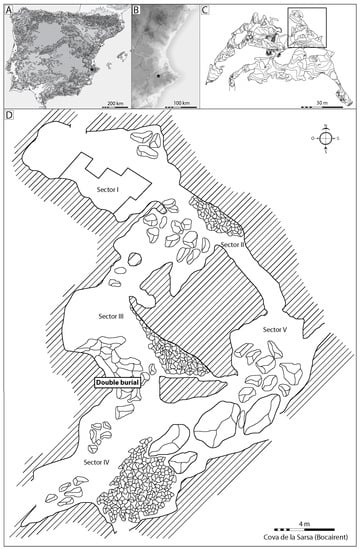

Cova de la Sarsa is situated in the municipality of Bocairent (València, Spain), 860 m above sea level, 650 m away from farming land, ca. 50 km away from the coastline in a straight line, and close to several river systems in the region like those of the Clariano and Serpis rivers (Figure 1). Opened in the karstic terrains formed by biomicrites and yellow loams of the Upper Cretaceous, its main entrance (trapezoid shape, 4.5 m wide × 2 m high) faces the northeast. This access quite possibly underwent modifications since Neolithic times, as fallen rocks along the entrance suggest there was a wide overhang before the cave’s main hall. The main hall (12 m long × 7 m wide × 3 m high) connects with the remaining of the cave towards the southeast through an abrupt step, after which there is a narrow passage that leads into another inner hall before the start of the complex galleries that form a karstic maze of 200 m with 47 m of slope.

Figure 1. Maps of Iberia (A) and Eastern Iberia (B) with Cova de la Sarsa highlighted in them, a plan of the broader cavity in which the site was found (C) and an archaeological plan of the site (D).

2. Cova de la Sarsa (València, Spain)

The first academic visit to the cave was carried out by abbe Henri Breuil in 1913, who named it “Cueva de la Zarza de San Blas”. Later on, Fernando Ponsell carried out the first excavation campaigns between 1927 and 1939 under the patronage of the Servicio de Investigación Prehistórica of the Diputación de Valencia. Since then, Cova de la Sarsa became a relevant site that was initially included as part of the cultural group defined by pottery decorated using a jagged shell, which Colominas named “Montserrat” or Montserratina-type. This was actually Cardial pottery, which was ascribed initially to the “Cultura Central” (or “Cultura de las Cuevas”) and the “Cultura de Almería”. Luis Pericot, influenced by Bosch Gimpera’s work, placed the new Cardial discoveries at Cova de la Sarsa inside the assemblage of Neo-Eneolithic pottery linked to the Bell Beaker world.

This classification was used until the publication of the stratigraphic sequence of the Esquerda de les Roques site (Torrelles de Foix, Barcelona), which demonstrated the older chronology of Cardial pottery and disassociated it from the Bell Beaker one. In the midst of this historiographic context, Cova de la Sarsa acquired more relevance thanks to the studies of Julián San Valero. This author showed the richness of the site, especially its cardial impression decoration, proposing its diffusion throughout Europe and Africa. Martínez Santa-Olalla placed the cave in the Hispano-Mauritanian Culture of which the most relevant element is cardial pottery.

The reference to Cova de la Sarsa then became mandatory for any synthesis on the Neolithic of Iberia and the Western Mediterranean, at a time where the study of other sites like Cueva de la Cocina (Dos Aguas), Cova de Malladetes (Barx) or Covacha de Llatas (Andilla) showed the existence of Mesolithic layers before the arrival of the Neolithic to the region. However, the archaeological sequence that explained the origin of the materials from Cova de la Sarsa, and that greatly influenced the future Iberian peninsula Neolithic expansion synthesis, was discovered in the northwest of Italy. In 1956, Luigi Bernabò Brea published the second volume of the excavations at the archaeological site of Arene Candide. His thoughts on the site drove the change from an Africanist Mediterranean perspective into a coastal continental Mediterranean perspective when he explained the diffusion of the Neolithic, discarding the African perspective in favor of one that considered that the cultural origin of the Mediterranean Neolithic must be searched for in the Near East instead. He also proposed that the impressed ware culture belonged to the Early Neolithic.

These new proposals were immediately included in the Spanish bibliography. Furthermore, a new Neolithic cave-site that presents similar archaeological evidence to Cova de la Sarsa was included at that time in the bibliography, Cova de l’Or, whose excavation was important to contextualize more precisely the Cova de la Sarsa materials. From then onwards, both Cova de la Sarsa and Cova de l’Or became key in any synthesis of the Iberian or Western Mediterranean Neolithic. In the review that Fortea undertook on the association of Epipalaeolithic and Neolithic contexts, Cova de la Sarsa and Cova de l’Or were defined as paradigm sites of “pure” Neolithic groups inside his “Dual model” proposal. They were portrayed as sites without influence from the previous Mesolithic levels and, therefore, pointing to the existence of a colonization process associated with the expansion of the Neolithic throughout the Mediterranean.

Soon thereafter, Cova de la Sarsa was excavated again under the supervision of María Dolores Asquerino, who contacted Vicent Casanova, a local who briefly dug the site in 1969 after he discovered some human remains in the crevice of the cave. Asquerino’s excavations are divided into two stages: the first one between 1971 and 1974, and the second one between 1978 and 1981. The main objective of these campaigns was to establish the archaeological sequence of the cave and contextualize the new findings. Unfortunately, she found that the stratigraphy of the cave was destroyed by the older excavations. Since then, Cova de la Sarsa stopped being a mandatory citation in the new ideas on the nature of the Neolithic expansion developed during the 1980s and 1990s, and does not appear much in the debates of the end of the 20th century. Only the study of specific materials, such as personal adornments, bone industry and pottery with certain symbolic significance associated with the discovered macroschematic art, was mentioned. Faunal remains have also been studied, suggesting that domestic animals (mainly Ovis aries and Capra hircus, but also Sus domesticus and Bos taurus) were the main source of meat even though wild species (mainly Cervus elaphus, Capra pyrenaica, Capreolus capreolus and Oryctolagus cuniculus) were still consumed. Although zooarchaeologists and a few radiocarbon dates suggest that most of the faunal remains are from the Neolithic period, the lack of stratigraphy, together with the existence of different moments of occupation of the cave, demand caution.

At the beginning of the 21st century, new studies have reactivated the research on Cova de la Sarsa, aiming to return the site into current debates on the Mediterranean Neolithic. Case studies on schematic rock art, polished stone objects, pottery, human remains and funerary contexts have been carried out. These studies have also allowed the incorporation of materials from this cave to more ambitious projects aimed to study proteins in domestic remains and perform ancient mitochondrial and nuclear DNA analysis in contexts of the Early Cardial Neolithic in the Western Mediterranean. Radiocarbon dates from a high number of human and faunal remains, together with isotopic analysis for reconstructing dietary practices, have also shed new lights into human subsistence and the use of the site from te Early Neolithic to the Medieval time period. More details and further references in [1].

References

- Salazar-García, D.C.; García-Borja, P.; Talamo, S.; Richards, M.P. Rediscovering Cova de la Sarsa (València, Spain): A Multidisciplinary Approach to One of the Key Early Neolithic Sites in the Western Mediterranean. Heritage 2023, 6, 6547-6569. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6100342

More

Information

Subjects:

Archaeology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

843

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

15 Oct 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No