Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Amin Mahmoud Thawabteh | -- | 2121 | 2023-09-26 11:45:00 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | Meta information modification | 2121 | 2023-09-27 05:26:15 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Thawabteh, A.M.; Naseef, H.A.; Karaman, D.; Bufo, S.A.; Scrano, L.; Karaman, R. Common Genera of Cyanobacteria and Their Characteristics. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/49658 (accessed on 08 February 2026).

Thawabteh AM, Naseef HA, Karaman D, Bufo SA, Scrano L, Karaman R. Common Genera of Cyanobacteria and Their Characteristics. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/49658. Accessed February 08, 2026.

Thawabteh, Amin Mahmood, Hani A Naseef, Donia Karaman, Sabino A. Bufo, Laura Scrano, Rafik Karaman. "Common Genera of Cyanobacteria and Their Characteristics" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/49658 (accessed February 08, 2026).

Thawabteh, A.M., Naseef, H.A., Karaman, D., Bufo, S.A., Scrano, L., & Karaman, R. (2023, September 26). Common Genera of Cyanobacteria and Their Characteristics. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/49658

Thawabteh, Amin Mahmood, et al. "Common Genera of Cyanobacteria and Their Characteristics." Encyclopedia. Web. 26 September, 2023.

Copy Citation

Blue-green algae, or cyanobacteria, may be prevalent in our rivers and tap water. These minuscule bacteria can grow swiftly and form blooms in warm, nutrient-rich water.

cyanobacteria blooms

cyanotoxins

Microcystis

Anabaena

Water treatment

Oscillatoria

Cylindrospermopsis

1. Introduction

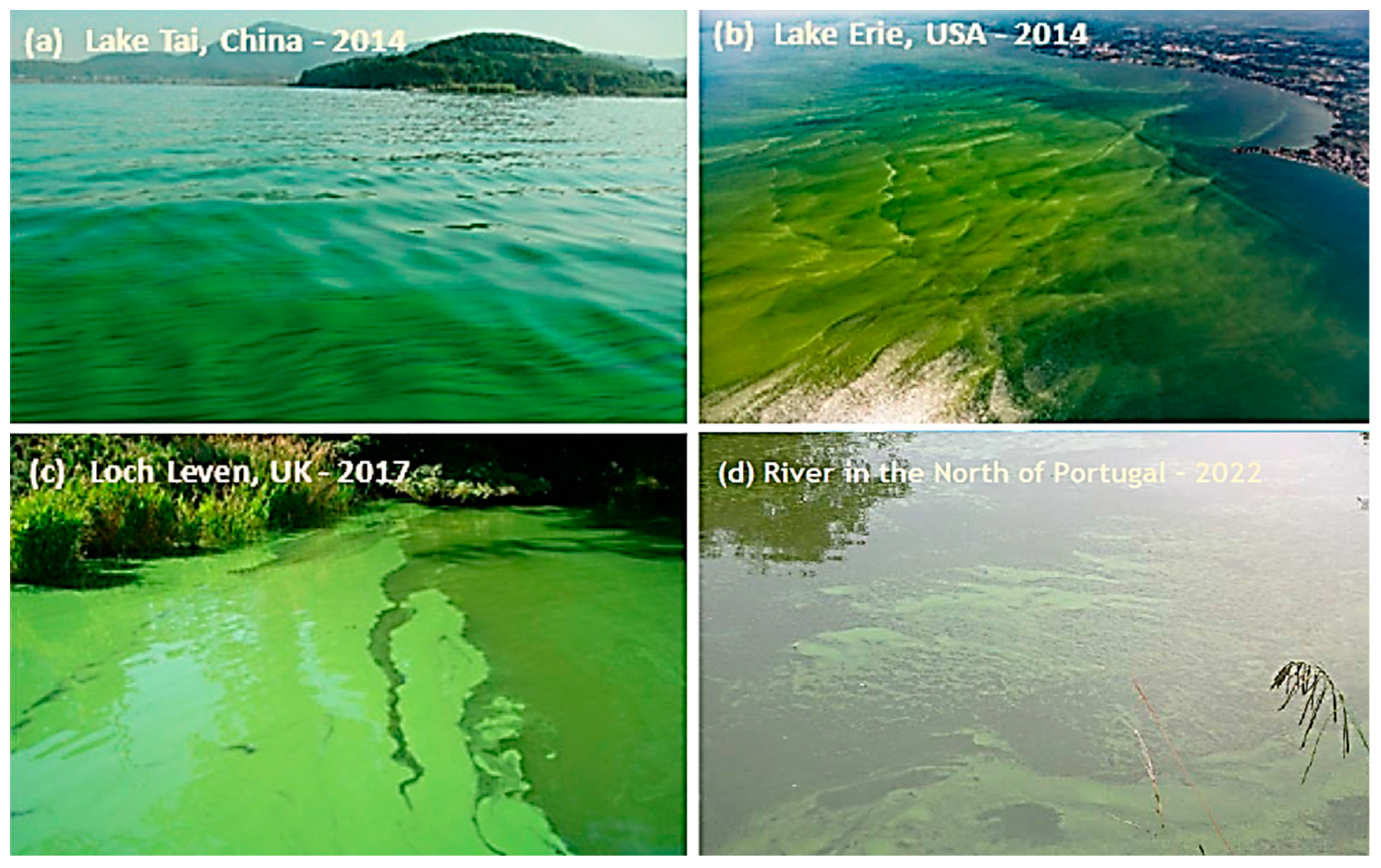

On occasion, drinking tap water results in an earthy flavor that is detectable right away. In addition to colored scum that can develop on river surfaces, foam can occasionally form on lake or rive’ surfaces. Cyanobacteria are depicted in Figure 1 [1][2][3][4] as the colorful scum and the earthy taste of tap water. This unpleasant, old-growth organism contaminates many of our freshwater supplies, which threatens human health. While cyanobacteria are naturally present in our rivers and water supply, green growth and environmental modifications brought on by human activity might hasten their spread [2][3][4][5][6][7]. Our rivers and tap water may include cyanobacteria. These tiny bacteria can swiftly produce blooms in warm, nutrient-rich water, endangering humans and aquatic life. Toxins produced by cyanobacteria include Microcystins, which are well-known for their toxicity and capacity to harm plants. These poisons contaminate rivers and streams and threaten our drinking water supply since they can sneak through standard water treatment systems unnoticed [6][7][8].

Figure 1. Cyanobacterial growth and dissemination on lake (a–c) and river (d) surfaces [3][8]. Reproduced with permission from Tao Lyu, Lirong Song, Qiuwen Chen, and Gang Pan, Water Journal; published by MDPI, 2020. Reproduced with permission from Moreira, C.; Vasconcelos, V.; Antunes, A., Earth Journal; published by MDPI, 2022.

Since these bacteria thrive in warmer climates, they pose a severe risk when river levels rise in the summer. To make matters worse, getting rid of cyanobacteria from nearby bodies of water can be challenging once a bloom has occurred. Because of this, we must comprehend the dangers of cyanobacteria and how to stop their spread in our drinking water [2][7][8][9].

In practically every freshwater ecosystem, cyanobacteria can be found alone or in combination with other organisms. In addition, there are numerous distinct cyanobacteria genera, each with unique properties. The common cyanobacteria genera discovered in freshwater systems are Synechococcus, Anabaena, Rivularia, Gloeotrichia, Oscillatoria, Cylindrospermopsis, Aphanizomenon, Planktothrix, Scytonema, Tolypothrix, Merismopedia, and Microcystis [10][11][12][13].

2. Microcystis: Colonial, Spherical Cells, Toxin Producer, Toxic, and Bloom-Forming

One of the most prevalent genera of cyanobacteria found in freshwater environments is Microcystis, a genus of colonial, spherical cells. Microcystis can produce toxins; they are poisonous and can cause blooms. Their colonies can be any shade of green, from deep olive to vivid blue-green. Microcystis colonies expand swiftly and have a milliliter cell density of over 1 million [11][12][13]. They prefer to form mats on the water’s surface along with other species like Anabaena, Oscillatoria, or Aphanizomenon and are photosynthetic organisms [14][15][16].

Moving water like rivers or streams and standing water like ponds, lakes, or reservoirs can harbor Microcystis. Because of the lower levels of oxygen and warmer temperatures throughout the summer, blooms are more likely to happen. Due to decreased oxygen levels and the development of chemicals that can harm humans and plant life, the blooms may result in drop-down water quality [17][18].

3. Anabaena: Filamentous, Heterocysts for Nitrogen Fixation and Diazotrophic

Anabaena inhabits environments in freshwater. These cyanobacteria are particularly important for their capacity to fix nitrogen since they include heterocyst cells capable of doing so. Anabaena also has akinetes cells, which act as protective spores and can withstand harsh environmental conditions [19][20].

The filaments that make up an Anabaena comprise individual trichome cells, which are one cell thick. Each trichome contains photosynthetic cells with a thick cell wall and an external peptidoglycan coating. The nucleoids, thylakoids, and carboxysomes of the cells are home to the enzymes involved in photosynthesis. Along the length of the trichome, heterocysts act as the central locations for nitrogen fixation [20][21][22]. Anabaena has undergone extensive research due to its ability to produce diazotrophic endospores that can be used to study other cyanobacterial species further. It is commonly used in aquatic systems to increase their nutritional content because of its ability to fix atmospheric nitrogen [22][23]. By doing so, it can supply other species with fixed nitrogen in settings where it is scarce or absent.

4. Oscillatoria: Filamentous, Motile, No Heterocysts

Oscillatoria is a widespread genus of freshwater cyanobacteria, the bacteria that cause bodies of water to get murkier and greener. It has a slimy, thin filamentous structure. Inhabiting shallow and deep regions of nutrient-rich water, such as seas, rivers, and lakes, Oscillatoria prefers to coil in an oscillatory motion [24][25].

It belongs to the cyanobacteria family and is not heterocytic, meaning it does not have heterocysts, a specific cell that fixes nitrogen in plants’ roots. Oscillatoria is frequently grouped with the Chroococcales family regarding their growth and physiological circumstances [26].

Under some circumstances, these mobile bacteria can create floating mats of colonies on the water’s surface. Oscillatoria can withstand dry seasons’ droughts thanks to the viscous slime that coats its cell walls. Furthermore, by utilizing nitrates to generate energy, it can survive in low light or even complete darkness because of its unique photosynthesis style [25][26][27].

5. Cylindrospermopsis: Filamentous, Motile, Toxin Producer

A filamentous and mobile genus of cyanobacteria called Cylindrospermopsis makes toxins. Freshwater systems like lakes and rivers and artificial reservoirs like ponds and canals frequently contain it. In temperate areas, this genus displays sporadic flowers in the summer [28].

Cylindrospermopsis spreads swiftly and takes over a system due to its motile habit, which makes it tough to eradicate. Despite being filamentous creatures, they can develop both deep blooms that can extend several meters below the surface of the water and enormous mats close to the water’s surface [29][30].

In addition to hepatotoxins (cyanotoxins), neurotoxins (ciguatoxins), and components of bacterial cell walls (lipopolysaccharides or LPS), Cylindrospermopsis species also produce toxins. Scientists must watch for these species in freshwater systems because these cyanotoxins are very hazardous to people and animals, even at low concentrations [29][30][31].

6. Aphanizomenon: Filamentous, Motile, Nitrogen Fixer

The genus Aphanizomenon of motile, free-floating filamentous cyanobacteria is widely found in freshwater bodies of water. They are known as nitrogen fixers because they can convert atmospheric nitrogen into a form that plants can utilize. As a result, they contribute nutrients to the food chain and maintain high water quality, making them vital to aquatic environments [32][33]. Certain Aphanizomenon species can harm humans and other animals when present in more significant proportions than usual. To further comprehend the potential risks these cyanobacteria pose, it is essential to frequently sample water and evaluate the levels of cyanobacterial metabolites [34]. Aphanizomenon is usually found in blossoms; therefore, that should also be considered. This indicates that an increase in their population may be caused by their quick growth, spurred by an abundance of nutrients or higher temperatures. It can help to prevent possible damage from increased toxin production or other negative impacts on aquatic plants and fauna by routinely checking for bloom indications [35][36].

7. Planktothrix: Filamentous, Motile, No Heterocysts

Numerous distinct species of cyanobacteria that have evolved to flourish in freshwater ecosystems comprise the Planktothrix genus. Planktothrix agardhii, P. rubescens, and P. limnetica are the most prevalent species. Due to their preference for nutrient-rich waters, these organisms are frequently found in eutrophic lakes with high levels of phosphate and nitrogen [37][38][39].

Phytotoxicity diffusion is the process of producing toxic exudates on the cell walls of Planktothrix species due to dense blooms that decompose. Due to the pigments (such as carotenoids) they produce, Planktothrix blooms can also cause water to become discolored [40]. In addition, Planktothrix is renowned for its capacity to multiply quickly and, under the right circumstances, to create dense aggregates or mats at the water’s surface. Optimal temperatures for Planktothrix development and survival in freshwater systems are between 15 and 25 °C and photosynthetically active radiation (PAR) [40][41].

8. Synechococcus: Unicellular and Colonial

The most prevalent genus of cyanobacteria is Synechococcus. It can be single-celled or colonial, consisting of one or more cells that can cluster and form filaments or colonies containing single or multiple cells. These colonies typically have a spherical form, a single gas exchange aperture, and a polysaccharide wall [42][43].

Synechococcus is renowned for its capacity to endure harsh conditions, including acidic and hypersaline waters. Due to its tolerance for high salt concentrations, it is also a significant species in coral reefs and soils, both aquatic environments. Its capacity for photosynthesis has also made it a vital component of the oxygen cycle in aquatic settings [44][45][46].

9. Rivularia: The Bubble-like Colonies

Rivularia create colonies that resemble bubbles, with each cell living inside a separate, protective “home”. Several characteristics set Rivularia apart from other cyanobacterial taxa. First, unlike most other cyanobacteria, Rivularia colonies are relatively solid in the water. The individual cells each have a distinct shape, with flat bottoms and rounded tops [47][48][49].

Additionally, depending on their environment, Rivularia colonies can appear very varied. When exposed to large amounts of light or oxygen, the colonies turn a deeper shade of green or even blue-black. However, colonies deprived of oxygen and light become paler and more transparent [50][51].

10. Gloeotrichia: Filamentous Cyanobacteria with Distinct Branching

The Gloeotrichia genus is distinguished by its distinctive branching, which gives its members the appearance of a starburst or a dandelion gone berserk. Due to their characteristic morphology, Gloeotrichia members are frequently observed in freshwater or brackish water habitats. They are anoxygenic phototrophs, producing sulfur rather than needing oxygen to use the light energy from photosynthesis [52][53].

These creatures’ internal sheaths have a spiral arrangement of cells that facilitates their movement through their environment, improving nutrition intake and mobility throughout your aquascape. The cell’s structure and surface area influence its interaction with its surroundings [53][54][55].

Most organisms have a variety of photosynthetic pigments in their photosynthetic system, allowing them to utilize light from locations where it is most abundant efficiently. Additionally, they have a variety of flagella to assist them in moving around in water deficient in nutrients or containing a lot of dissolved materials, such as salts and metals [55][56].

11. Scytonema: Irregularly Branched Filaments

Cyanobacteria belonging to the genus Scytonema have filaments that are erratically branched. When growing in colonies, cells can form cords, tufts, and even mats and are typically oriented spirally. The second name of this particular cyanobacterium species refers to the color of its distinctive brilliant reddish-brown spores. It can be found on mosses and lichens and often grows on damp surfaces [57][58].

Scytonema stands out from other cyanobacteria in several ways. It does not require light for photosynthesis, enabling it to flourish in dark places like caves or deep-sea cracks. A bud forms from the side of the bacteria cell and splits off to create a new organism, which is how they mainly reproduce [58][59].

They can also continue for extended periods without water because they enter a latent stage when they do not require oxygen. On the other hand, several species have unique pigments that enable them to absorb various light wavelengths, allowing them to adapt to multiple habitats [58][59][60].

12. Tolypothrix: Pseudoparenchymatous Filaments

Because of its pseudo-parenchymatous filaments, Tolypothrix can be identified. As a filamentous cyanobacterium that resembles a thread, Tolypothrix can join with other Tolypothrix cells to form lengthy chains of cells. This genus is extensively distributed worldwide and can be found in fresh and saltwater settings [61].

Typically comprised of four to six cells, Tolypothrix cells are protected from external challenges like UV radiation and drying out by a rigid coating consisting of glycoproteins and polysaccharides. The glycoprotein sheath keeps Their cell walls together, making it easier for them to build long chains [61][62][63].

Contrary to other cyanobacterial genera, such as rivularia or Gloeotrichia, Tolypothrix filaments rely on robust glycoprotein sheaths to make these connections rather than a visible sheath or stalk-like structure. This distinctive structure provides them a distinct edge when adapting to various settings, which explains why they are such a widespread genus globally [62][64].

13. Merismopedia: Cubicpacket-Shaped Cells

Merismopedia, a common genus of cyanobacteria, has a distinctive cubic packet-shaped cell and can split up to four times before finally dispersing. Merismopedia cells typically come in two shapes: flattened and cubed, ranging in size from 2 to 6 m [65][66]. When these cells cluster together in their surroundings, their morphology enables them to create a slimy, jelly like substance. This characteristic slimy mass typically comprises numerous layers with various types of Merismopedia cells [67].

Although it can also be found in wet soil and other moist habitats, Merismopedia is primarily found in oceans, seas, and other aquatic environments. Additionally, Merismopedia is frequently linked to cyanobacterial mats because of its ability to adapt to different light, temperature, and salt concentrations [68][69].

Merismopedia needs specific minerals like potassium and nitrogen to thrive appropriately and does it best in direct sunshine. It can grow rather quickly under ideal circumstances, such as temperatures between 25 and 35 °C and pH levels between 6 and 8.1. It is crucial to understand where Merismopedia is typically located and how to recognize it because this tiny but mighty genus of cyanobacteria can create toxins that can be dangerous to people if swallowed or even inhaled [68][69][70].

References

- Bertani, I.; Steger, C.E.; Obenour, D.R.; Fahnenstiel, G.L.; Bridgeman, T.B.; Johengen, T.H.; Sayers, M.J.; Shuchman, R.A.; Scavia, D. Tracking cyanobacteria blooms: Do different monitoring approaches tell the same story? Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 575, 294–308.

- Lürling, M.; Mello, M.M.E.; Van Oosterhout, F.; de Senerpont Domis, L.; Marinho, M.M. Response of natural cyanobacteria and algae assemblages to a nutrient pulse and elevated temperature. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 1851.

- Lyu, T.; Song, L.; Chen, Q.; Pan, G. Lake and river restoration: Method, evaluation and management. Water 2020, 12, 977.

- Metcalf, J.S.; Codd, G.A. Co-occurrence of cyanobacteria and cyanotoxins with other environmental health hazards: Impacts and implications. Toxins 2020, 12, 629.

- Zahra, Z.; Choo, D.H.; Lee, H.; Parveen, A. Cyanobacteria: Review of current potentials and applications. Environments 2020, 7, 13.

- Chorus, I.; Welker, M. Toxic Cyanobacteria in Water: A Guide to Their Public Health Consequences, Monitoring and Management; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2021.

- Vidal, L.; Ballot, A.; Azevedo, S.; Padisák, J.; Welker, M. Introduction to cyanobacteria. In Toxic Cyanobacteria in Water, 2nd ed.; Chorus, I., Welker, M., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2021; pp. 163–211.

- Moreira, C.; Vasconcelos, V.; Antunes, A. Cyanobacterial blooms: Current knowledge and new perspectives. Earth 2022, 3, 127–135.

- Burford, M.; Carey, C.; Hamilton, D.; Huisman, J.; Paerl, H.; Wood, S.; Wulff, A. Perspective: Advancing the research agenda for improving understanding of cyanobacteria in a future of global change. Harmful Algae 2020, 91, 101601.

- Patel, V.K.; Sundaram, S.; Patel, A.K.; Kalra, A. Characterization of seven species of cyanobacteria for high-quality biomass production. Arab. J. Sci. Eng. 2018, 43, 109–121.

- Wei, N.; Hu, L.; Song, L.; Gan, N. Microcystin-bound protein patterns in different cultures of Microcystis aeruginosa and field samples. Toxins 2016, 8, 293.

- Huisman, J.; Codd, G.A.; Paerl, H.W.; Ibelings, B.W.; Verspagen, J.M.; Visser, P.M. Cyanobacterial blooms. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2018, 16, 471–483.

- Kurmayer, R.; Christiansen, G.; Chorus, I. The abundance of microcystin-producing genotypes correlates positively with colony size in Microcystis sp. and determines its microcystin net production in Lake Wannsee. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2003, 69, 787–795.

- Radkova, M.; Stefanova, K.; Uzunov, B.; Gärtner, G.; Stoyneva-Gärtner, M. Morphological and molecular identification of microcystin-producing cyanobacteria in nine shallow Bulgarian water bodies. Toxins 2020, 12, 39.

- Xiao, M.; Li, M.; Reynolds, C.S. Colony formation in the cyanobacterium Microcystis. Biol. Rev. 2018, 93, 1399–1420.

- Jacinavicius, F.R.; Pacheco, A.B.F.; Chow, F.; da Costa, G.C.V.; Kalume, D.E.; Rigonato, J.; Schmidt, E.C.; Sant’Anna, C.L. Different ecophysiological and structural strategies of toxic and non-toxic Microcystis aeruginosa (cyanobacteria) strains assessed under culture conditions. Algal Res. 2019, 41, 101548.

- Dick, G.J.; Duhaime, M.B.; Evans, J.T.; Errera, R.M.; Godwin, C.M.; Kharbush, J.J.; Nitschky, H.S.; Powers, M.A.; Vanderploeg, H.A.; Schmidt, K.C. The genetic and ecophysiological diversity of Microcystis. Environ. Microbiol. 2021, 23, 7278–7313.

- Park, B.S.; Li, Z.; Kang, Y.-H.; Shin, H.H.; Joo, J.-H.; Han, M.-S. Distinct bloom dynamics of toxic and non-toxic Microcystis (cyanobacteria) subpopulations in Hoedong Reservoir (Korea). Microb. Ecol. 2018, 75, 163–173.

- Czarny, K.; Krawczyk, B.; Szczukocki, D. Toxic effects of bisphenol A and its analogues on cyanobacteria Anabaena variabilis and Microcystis aeruginosa. Chemosphere 2021, 263, 128299.

- Österholm, J.; Popin, R.V.; Fewer, D.P.; Sivonen, K. Phylogenomic analysis of secondary metabolism in the toxic cyanobacterial genera Anabaena, Dolichospermum and Aphanizomenon. Toxins 2020, 12, 248.

- Zervou, S.-K.; Moschandreou, K.; Paraskevopoulou, A.; Christophoridis, C.; Grigoriadou, E.; Kaloudis, T.; Triantis, T.M.; Tsiaoussi, V.; Hiskia, A. Cyanobacterial toxins and peptides in Lake Vegoritis, Greece. Toxins 2021, 13, 394.

- Gugger, M.; Lyra, C.; Henriksen, P.; Coute, A.; Humbert, J.-F.; Sivonen, K. Phylogenetic comparison of the cyanobacterial genera Anabaena and Aphanizomenon. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2002, 52, 1867–1880.

- Bramburger, A.J.; Filstrup, C.T.; Reavie, E.D.; Sheik, C.S.; Haffner, G.D.; Depew, D.C.; Downing, J.A. Paradox versus paradigm: A disconnect between understanding and management of freshwater cyanobacterial harmful algae blooms. Freshw. Biol. 2023, 68, 191–201.

- Meriluoto, J.; Sandström, A.; Eriksson, J.; Remaud, G.; Graig, A.G.; Chattopadhyaya, J. Structure and toxicity of a peptide hepatotoxin from the cyanobacterium Oscillatoria agardhii. Toxicon 1989, 27, 1021–1034.

- Eriksson, J.E.; Meriluoto, J.A.; Lindholm, T. Accumulation of a peptide toxin from the cyanobacterium Oscillatoria agardhii in the freshwater mussel Anadonta cygnea. Hydrobiologia 1989, 183, 211–216.

- Bon, I.C.; Salvatierra, L.M.; Lario, L.D.; Morató, J.; Pérez, L.M. Prospects in cadmium-contaminated water management using free-living cyanobacteria (Oscillatoria sp.). Water 2021, 13, 542.

- Ilieva, V.; Kondeva-Burdina, M.; Georgieva, T.; Pavlova, V. Toxicity of cyanobacteria. Organotropy of cyanotoxins and toxicodynamics of cyanotoxins by species. Pharmacia 2019, 66, 91–97.

- Yang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Cai, F.; Liu, X.; Wang, Y.; Li, R. Toxicity-associated changes in the invasive cyanobacterium Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii in response to nitrogen fluctuations. Environ. Pollut. 2018, 237, 1041–1049.

- Willis, A.; Woodhouse, J.N.; Ongley, S.E.; Jex, A.R.; Burford, M.A.; Neilan, B.A. Genome variation in nine co-occurring toxic Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii strains. Harmful Algae 2018, 73, 157–166.

- Rzymski, P.; Horyn, O.; Budzyńska, A.; Jurczak, T.; Kokociński, M.; Niedzielski, P.; Klimaszyk, P.; Falfushynska, H. A report of Cylindrospermopsis raciborskii and other cyanobacteria in the water reservoirs of power plants in Ukraine. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2018, 25, 15245–15252.

- Santos, G.D.; Vilar, M.C.P.; de Oliveira Azevedo, S.M.F. Acute toxicity of neurotoxin-producing Raphidiopsis (Cylindrospermopsis) raciborskii ITEP-A1 (Cyanobacteria) on the neotropical cladoceran Macrothrix spinosa. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Contam. 2020, 15, 1–8.

- Falfushynska, H.; Horyn, O.; Osypenko, I.; Rzymski, P.; Wejnerowski, Ł.; Dziuba, M.K.; Sokolova, I.M. Multibiomarker-based assessment of toxicity of central European strains of filamentous cyanobacteria Aphanizomenon gracile and Raphidiopsis raciborskii to zebrafish Danio rerio. Water Res. 2021, 194, 116923.

- Jin, H.; Ma, H.; Gan, N.; Wang, H.; Li, Y.; Wang, L.; Song, L. Non-targeted metabolomic profiling of filamentous cyanobacteria Aphanizomenon flos-aquae exposed to a concentrated culture filtrate of Microcystis aeruginosa. Harmful Algae 2022, 111, 102170.

- Wejnerowski, Ł.; Falfushynska, H.; Horyn, O.; Osypenko, I.; Kokociński, M.; Meriluoto, J.; Jurczak, T.; Poniedziałek, B.; Pniewski, F.; Rzymski, P. In Vitro Toxicological screening of stable and senescing cultures of Aphanizomenon, Planktothrix, and Raphidiopsis. Toxins 2020, 12, 400.

- Puschner, B. Cyanobacterial (blue-green algae) toxins. In Veterinary Toxicology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 763–777.

- Yancey, C.E.; Mathiesen, O.; Dick, G.J. Transcriptionally active nitrogen fixation and biosynthesis of diverse secondary metabolites by Dolichospermum and Aphanizomenon-like Cyanobacteria in western Lake Erie Microcystis blooms. Harmful Algae 2023, 124, 102408.

- Benayache, N.-Y.; Afri-Mehennaoui, F.-Z.; Kherief-Nacereddine, S.; Vo-Quoc, B.; Hushchyna, K.; Nguyen-Quang, T.; Bouaïcha, N. Massive fish death associated with the toxic cyanobacterial Planktothrix sp. bloom in the Béni-Haroun Reservoir (Algeria). Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2022, 29, 80849–80859.

- Pawlik-Skowrońska, B.; Toporowska, M.; Mazur-Marzec, H. Toxic oligopeptides in the cyanobacterium Planktothrix agardhii-dominated blooms and their effects on duckweed (Lemnaceae) development. Knowl. Manag. Aquat. Ecosyst. 2018, 419, 41.

- Toporowska, M.; Mazur-Marzec, H.; Pawlik-Skowrońska, B. The effects of cyanobacterial bloom extracts on the biomass, Chl-a, MC and other oligopeptides contents in a natural Planktothrix agardhii population. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 2881.

- Mallia, V.; Ivanova, L.; Eriksen, G.S.; Harper, E.; Connolly, L.; Uhlig, S. Investigation of in vitro endocrine activities of Microcystis and Planktothrix cyanobacterial strains. Toxins 2020, 12, 228.

- Zastepa, A.; Miller, T.R.; Watson, L.C.; Kling, H.; Watson, S.B. Toxins and other bioactive metabolites in deep chlorophyll layers containing the cyanobacteria Planktothrix cf. isothrix in two Georgian Bay Embayments, Lake Huron. Toxins 2021, 13, 445.

- Zhang, Y.; He, D.; Bu, Z.; Li, Y.; Guo, J.; Li, Q. The transcriptomic analysis revealed sulfamethoxazole stress at environmentally relevant concentration on the mechanisms of toxicity of cyanobacteria Synechococcus sp. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107637.

- Te, S.H.; Kok, J.W.K.; Luo, R.; You, L.; Sukarji, N.H.; Goh, K.C.; Sim, Z.Y.; Zhang, D.; He, Y.; Gin, K.Y.-H. Coexistence of Synechococcus and Microcystis Blooms in a Tropical Urban Reservoir and Their Links with Microbiomes. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 1613–1624.

- Zeng, H.; Hu, X.; Ouyang, S.; Zhou, Q. Microplastics Weaken the Adaptability of Cyanobacterium Synechococcus sp. to Ocean Warming. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 9005–9017.

- Sarker, I.; Moore, L.R.; Tetu, S.G. Investigating zinc toxicity responses in marine Prochlorococcus and Synechococcus. Microbiology 2021, 167, 001064.

- Moradinejad, S.; Trigui, H.; Guerra Maldonado, J.F.; Shapiro, J.; Terrat, Y.; Zamyadi, A.; Dorner, S.; Prévost, M. Diversity assessment of toxic cyanobacterial blooms during oxidation. Toxins 2020, 12, 728.

- Breinlinger, S.; Phillips, T.J.; Haram, B.N.; Mareš, J.; Martínez Yerena, J.A.; Hrouzek, P.; Sobotka, R.; Henderson, W.M.; Schmieder, P.; Williams, S.M. Hunting the eagle killer: A cyanobacterial neurotoxin causes vacuolar myelinopathy. Science 2021, 371, eaax9050.

- Metcalf, J.; Souza, N. Cyanobacteria and their toxins. In Separation Science and Technology; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 11, pp. 125–148.

- Mlewski, E.C.; Pisapia, C.; Gomez, F.; Lecourt, L.; Soto Rueda, E.; Benzerara, K.; Ménez, B.; Borensztajn, S.; Jamme, F.; Réfrégiers, M. Characterization of pustular mats and related rivularia-rich laminations in oncoids from the Laguna Negra lake (Argentina). Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 996.

- Nowruzi, B.; Bouaïcha, N.; Metcalf, J.S.; Porzani, S.J.; Konur, O. Plant-cyanobacteria interactions: Beneficial and harmful effects of cyanobacterial bioactive compounds on soil-plant systems and subsequent risk to animal and human health. Phytochemistry 2021, 192, 112959.

- Lyimo, T.J. The Microalgae and Cyanobacteria of Chwaka Bay. In People, Nature and Research in Chwaka Bay, Zanzibar, Tanzania; de la Torre-Castro, M., Lyimo, T.J., Eds.; WIOMSA: Zanzibar Town, Tanzania, 2012; pp. 125–141. ISBN 978-9987-9559-1-6.

- Gabyshev, V.; Davydov, D.; Vilnet, A.; Sidelev, S.; Chernova, E.; Barinova, S.; Gabysheva, O.; Zhakovskaya, Z. Gloeotrichia cf. natans (Cyanobacteria) in the Continuous Permafrost Zone of Buotama River, Lena Pillars Nature Park, in Yakutia (Russia). Water 2023, 15, 2370.

- Namsaraev, Z.; Melnikova, A.; Ivanov, V.; Komova, A.; Teslyuk, A. Cyanobacterial Bloom in the World Largest Freshwater Lake Baikal. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2018; p. 032039.

- Kirpenko, N.; Krot, Y.G.; Usenko, O. Toxicological Aspects of the Surface Water” Blooms”(a Review). Hydrobiol. J. 2020, 56, 3–16.

- Genuario, D.B.; Andreote, A.P.D.; Vaz, M.G.M.V.; Fiore, M.F. Heterocyte-forming cyanobacteria from Brazilian saline-alkaline lakes. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2017, 109, 105–112.

- Wang, M.; Zhang, J.; He, S.; Yan, X. A review study on macrolides isolated from cyanobacteria. Mar. Drugs 2017, 15, 126.

- Klemm, L.C.; Czerwonka, E.; Hall, M.L.; Williams, P.G.; Mayer, A.M. Cyanobacteria scytonema javanicum and scytonema ocellatum lipopolysaccharides elicit release of superoxide anion, matrix-metalloproteinase-9, cytokines and chemokines by rat microglia in vitro. Toxins 2018, 10, 130.

- Wood, S.A.; Kelly, L.; Bouma-Gregson, K.; Humbert, J.F.; Laughinghouse IV, H.D.; Lazorchak, J.; McAllister, T.; McQueen, A.; Pokrzywinski, K.; Puddick, J. Toxic benthic freshwater cyanobacterial proliferations: Challenges and solutions for enhancing knowledge and improving monitoring and mitigation. Freshw. Biol. 2020, 65, 1824.

- Jaiswal, T.P.; Chakraborty, S.; Sharma, S.; Mishra, A.; Mishra, A.K.; Singh, S.S. Prospects of a hot spring–originated novel cyanobacterium, Scytonema ambikapurensis, for wastewater treatment and exopolysaccharide-enriched biomass production. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 53424–53444.

- Barzegari Naeeni, R.; Amani, J.; Nobakht, M.; Mirhosseini, S.A.; Mahmoodzadeh Hosseini, H. Human Risk of Saxitoxins Poisoning: Incidence, Source, Toxicity and Diagnostic Methods. J. Mar. Med. 2022, 4, 16–25.

- Dulić, T.; Meriluoto, J.; Malešević, T.P.; Gajić, V.; Važić, T.; Tokodi, N.; Obreht, I.; Kostić, B.; Kosijer, P.; Khormali, F. Cyanobacterial diversity and toxicity of biocrusts from the Caspian Lowland loess deposits, North Iran. Quat. Int. 2017, 429, 74–85.

- Velu, C.; Cirés, S.; Brinkman, D.L.; Heimann, K. Effect of CO2 and metal-rich waste water on bioproduct potential of the diazotrophic freshwater cyanobacterium, Tolypothrix sp. Heliyon 2019, 5, e01549.

- Singh, A.K.; Singh, A.; Gaurav, N.; Srivastava, A.; Kumar, A. Morphology & Ecology of Selected BGA (Aulosira, Tolypothrix, Anabaena, Nostoc). Int. J. Gen. Med. Pharm. 2018, 5, 37–46.

- Yadav, P.; Gupta, R.K.; Singh, R.P.; Yadav, P.K.; Patel, A.K.; Pandey, K.D. Role of cyanobacteria in green remediation. In Sustainable Environmental Clean-Up; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 187–210.

- Krings, M.; Harper, C.J. A microfossil resembling Merismopedia (cyanobacteria) from the 410-million-yr-old rhynie and windyfield cherts-Rhyniococcus uniformis revisited. Nova Hedwig. 2019, 108, 17–35.

- Curren, E.; Leong, S.C.Y. Natural and anthropogenic dispersal of cyanobacteria: A review. Hydrobiologia 2020, 847, 2801–2822.

- Poot-Delgado, C.A.; Okolodkov, Y.B.; Aké-Castillo, J.A. Potentially harmful cyanobacteria in oyster banks of Términos lagoon, southeastern Gulf of Mexico. Acta Biol. Colomb. 2018, 23, 51–58.

- Bakr, A. Occurrence of Merismopedia minima in a drinking water treatment plant in Sohag city and removal of their microcystins by sediments. Egypt. J. Bot. 2022, 62, 659–669.

- Youn, S.J.; Kim, H.N.; Yu, S.J.; Byeon, M.S. Cyanobacterial occurrence and geosmin dynamics in Paldang Lake watershed, South Korea. Water Environ. J. 2020, 34, 634–643.

- Häggqvist, K.; Akçaalan, R.; Echenique-Subiabre, I.; Fastner, J.; Horecká, M.; Humbert, J.F.; Izydorczyk, K.; Jurczak, T.; Kokociński, M.; Lindholm, T. Case Studies of Environmental Sampling, Detection, and Monitoring of Potentially Toxic Cyanobacteria. In Handbook of Cyanobacterial Monitoring and Cyanotoxin Analysis; Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016; pp. 70–83.

More

Information

Subjects:

Chemistry, Medicinal

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

2.7K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

27 Sep 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No