Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | George Marakomichelakis | -- | 2099 | 2023-09-25 11:20:08 | | | |

| 2 | Jessie Wu | + 3 word(s) | 2102 | 2023-09-26 03:58:41 | | | | |

| 3 | Jessie Wu | Meta information modification | 2102 | 2023-09-26 04:02:51 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Stanek, A.; Mosti, G.; Nematillaevich, T.S.; Valesky, E.M.; Planinšek Ručigaj, T.; Boucelma, M.; Marakomichelakis, G.; Liew, A.; Fazeli, B.; Catalano, M.; et al. Venous Ulcers. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/49593 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Stanek A, Mosti G, Nematillaevich TS, Valesky EM, Planinšek Ručigaj T, Boucelma M, et al. Venous Ulcers. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/49593. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Stanek, Agata, Giovanni Mosti, Temirov Surat Nematillaevich, Eva Maria Valesky, Tanja Planinšek Ručigaj, Malika Boucelma, George Marakomichelakis, Aaron Liew, Bahar Fazeli, Mariella Catalano, et al. "Venous Ulcers" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/49593 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Stanek, A., Mosti, G., Nematillaevich, T.S., Valesky, E.M., Planinšek Ručigaj, T., Boucelma, M., Marakomichelakis, G., Liew, A., Fazeli, B., Catalano, M., & Patel, M. (2023, September 25). Venous Ulcers. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/49593

Stanek, Agata, et al. "Venous Ulcers." Encyclopedia. Web. 25 September, 2023.

Copy Citation

Venous leg ulcers (VLUs) are the most severe complication caused by the progression of chronic venous insufficiency. They account for approximately 70–90% of all chronic leg ulcers (CLUs). A total of 1% of the Western population will suffer at some time in their lives from a VLU. Furthermore, most CLUs are VLUs, defined as chronic leg wounds that show no tendency to heal after three months of appropriate treatment or are still not fully healed at 12 months. The essential feature of VLUs is their recurrence.

venous ulcer

recurrent venous ulcer

compression therapy

conservative treatment

invasive treatment

costs

prevention

1. Definition of Venous Leg Ulcer

According to the CEAP classification, revised in 2004, a venous leg ulcer (VLU) is defined as a full-thickness skin defect, most frequently in the lower leg and ankle region, that fails to heal spontaneously and is sustained by venous hypertension due to chronic venous disease [1]. Venous leg ulcers (VLUs) usually occur at the malleolar part on the medial and lateral sides of the ankle. However, they also may appear on the supra-malleolar and infra-malleolar areas of the leg and foot [2]. Furthermore, most VLUs are chronic leg ulcers (CLUs), defined as chronic leg wounds that show no tendency to heal after three months of appropriate treatment or are still not fully healed at 12 months [3]. Moreover, it is estimated that between 40% and 50% remain active between 6 and 12 months, and that 10% remain active up to 5 years [4]. It also has been shown that a VLU that fails to decrease in size by 30% (percentage area reduction) of its initial size over the first four weeks of treatment has a 68% probability of failing to heal within 24 weeks [5].

2. Pathophysiology of Venous Ulcers

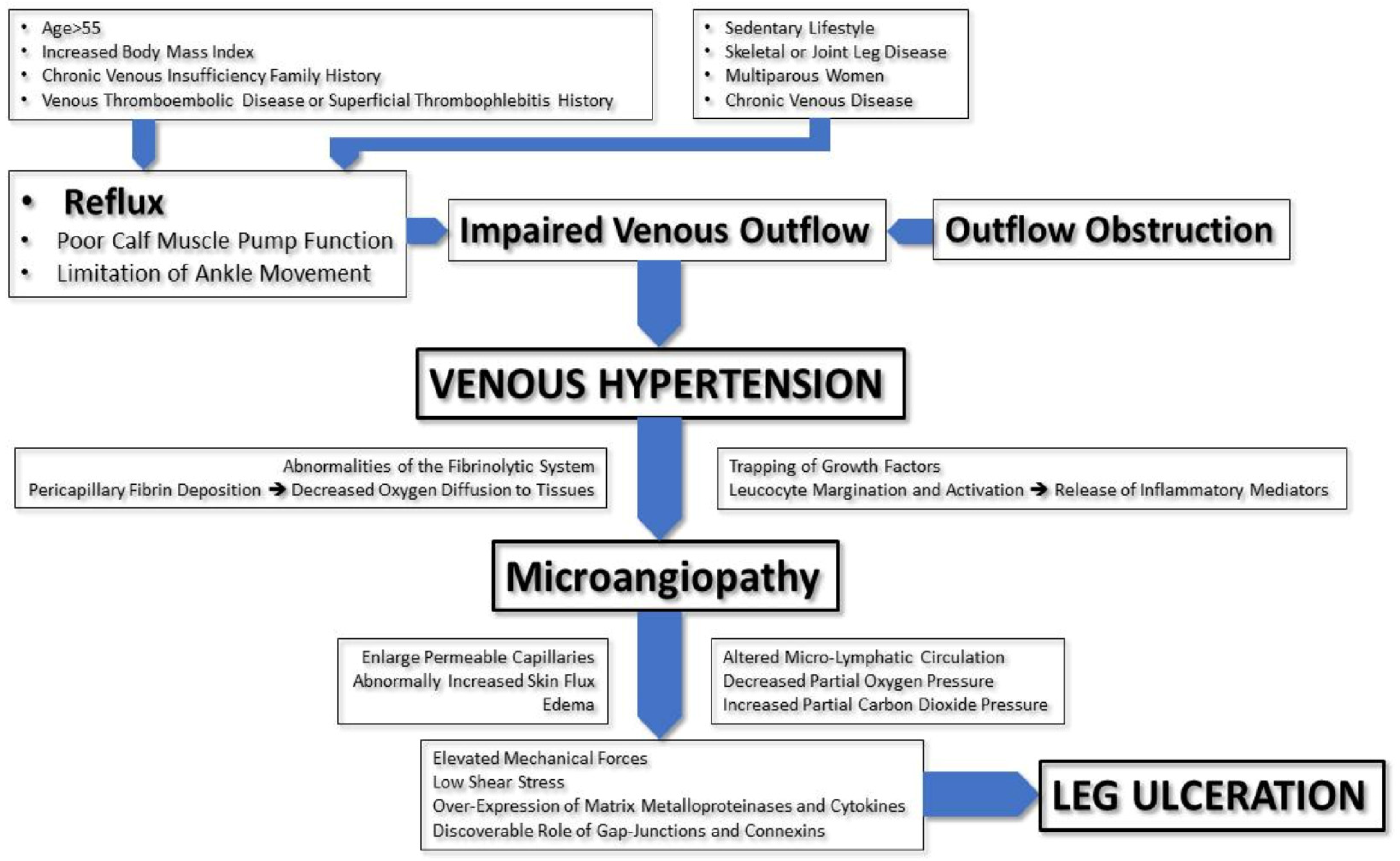

Patients with venous leg ulcers have venous hypertension and abnormally sustained venous pressure elevation upon ambulation (normal venous pressure decreases with walking), which results from vein reflux or outflow obstruction.

Venous outflow may also be impaired due to poor calf muscle pump function, which damages the venous system’s ability to overcome the venous blood return to the heart. The limitation of ankle movement seems to be an essential contributor to calf muscle pump failure and a risk factor for ulceration [6]. Several risk factors of VLU development have been identified, including, among others, an age older than 55 years, an increased body mass index (BMI), a family history of CVI, a history of venous thromboembolism disease and superficial thrombophlebitis, a sedentary lifestyle, skeletal or joint disease of the legs, multiparous women, and severe stages of chronic venous diseases (lipodermatosclerosis, active or healed venous ulcers in history) [7].

Although venous hypertension results in ulceration, the exact mechanism remains unclear. Several hypotheses have been proposed, such as abnormalities of the fibrinolytic system, peripapillary fibrin deposition causing decreased oxygen diffusion to tissues, the trapping of growth factors by extravasated macromolecules around the vessels and in the dermis, limiting their function, and leucocyte margination and activation with the subsequent local release of inflammatory mediators [8]. Consequent microcirculatory changes lead to venous hypertensive microangiopathy (enlarged permeable capillaries, abnormally increased skin flux, edema, altered microlymphatic circulation, decreased partial pressure of oxygen, and increased carbon dioxide) that results in ulceration [9].

The effect on the microcirculation begins with altered shear stress on the endothelial cells, causing them to release vasoactive agents and express selectins, inflammatory molecules, chemokines, and prothrombotic precursors [10][11]. Mechanical forces and low shear stress are sensed by the endothelial cells via intercellular adhesion molecules-1 (ICAM1, CD 54), vascular cell adhesion molecules1 (VCAM-1, CD-106), and endothelial leucocyte adhesion molecule1 (CD-62, E-selectin). CVD patients have increased expressions of ICAM-1 and VCAM-1. A key component of inflammation in VLUs is the increased expressions of matrix metalloproteinases and the production of cytokines (Transforming growth factor-β1, Tumor necrosis factor-α, Interleukin-1) [12].

Another area of research in the pathophysiology of LVUs is gap junctions. Gap junctions are proteins that play critical roles in the pathogenesis of chronic wounds, mainly involved in inflammation, edema, and fibrosis. Connexins (a component of gap junctions) are abnormally elevated in the wound margins of VLUs. Connexins seem to play an essential role in the inflammatory response and VLU healing [13].

The pathophysiology of venous ulcers is shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Pathophysiology of venous ulcers.

3. Diagnosis of Venous Ulcers

The diagnosis of leg ulcers is based on medical history, clinical assessments, functional/diagnostics testing, blood tests, biopsy, bacteriologic or mycologic swabs, histopathology, and direct immunofluorescence [14][15][16][17] (Table 1). The clinical diagnosis as the first step is available everywhere, allowing for the diagnosis of the majority of VLUs. In the next step, several complementary diagnostic procedures are used [12][14] (Table 2).

Table 1. Diagnostics of leg ulcers.

| Medical History | |

| History of present symptoms and signs | Duration and presence of symptoms: Cramps, tired legs, swollen legs, heavy legs, restless legs, venous claudication, itching Pain: distribution, intensity (VAS score 0–10), duration, intermittent, during night/day, pain during dressing changes |

| Duration and presence of signs: Varicose veins: duration, uni-/bilateral, bleeding from the vein Swelling: uni-/bilateral, region: around the ankle, whole leg, relation to standing/sitting a whole day Active ulcer: spontaneous/post-traumatic, duration, dressings (type/frequency of changes), compression therapy |

|

| Past signs | Previously healed/recurrent ulcers: spontaneous/post-traumatic, duration, dressings, compression therapy DVT/SVT/PE: time of occurrence, therapy Previous leg fractures Previous surgical therapy |

| Comorbidities | Diabetes mellitus, hypertension, chronic renal insufficiency, heart failures, malignancy, rheumatoid arthritis, PAD, obesity, back problems |

| Treatment | Treatment of present and past varicose veins: laser, sclerotherapy, surgical treatment, endovenous ablation (non-thermal/thermal), compression therapy (short-/long-stretch bandages, stockings, Velcro® materials) Treatment of present ulcer: dressings, therapy of surrounding skin, compression; where and by whom treatment is provided (patient/nurse/in hospital/in healthcare center); medications (anticoagulants, contraceptives, hormone replacement therapy, antidiabetics antihypertensives, immunosuppressive therapy, other) |

| Allergies | Contact/systemic drug reaction |

| Pregnancy | When, number, signs, and symptoms during pregnancy, therapy of signs/symptoms |

| Family history | Presence of varicose veins in relatives, ulcers, DVT |

| Occupation | Prolonged standing/sitting |

| Bad habits | Smoking, alcohol consumption, drug use |

| Trauma | Mechanical, chemical, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, etc. |

| Clinical Assessment | |

| Inspection and palpation | Mobility, BMI Presence of varicose veins, corona phlebectatica Limb swelling: Stemmer’s sign, non-pitting/pitting, Bisgaard sign Skin changes: hyperpigmentations/redness (whole leg/during the vein, eczema), lipodermatosclerosis/atrophie blanche Peripheral arterial pulses, capillarity refilling Groin lymph nodes Leg temperature (cold/warm) Scars after previous surgical therapy, trauma Trophic changes in nails |

| Leg ulcers: where, number, size, wound bed (necrosis, fibrin (ogen), granulation tissue, epithelial tissue, isles in wound bed), edges, surrounding skin, smell, presence of infection, wound exudate, possibility of ankle movements |

|

| Functional/Diagnostics Testing | |

| Venous system | CW Doppler: S–F junction reflux Duplex US Photoplethysmography |

| Arterial system | Measurement of ABI (with CW Doppler; automatic) |

| Lymphatic system | Limb circumferences, perimetry, bioimpedance |

| Non-invasive/invasive tests | Monofilament test Capillaroscopy Venography IVUS Angiography Lymphoscintigraphy CT MR |

| Microbiological | Swab for pathogenic bacteria and fungi |

| Skin/ulcer biopsy | Pathohistological examination Direct immunofluorescence |

| Blood tests | Complete/differential blood count, C-reactive protein, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, blood glucose, HBA1c, blood lipids electrolytes, urea, creatinine, liver function tests tests of coagulations total proteins, circulating immune complex, immunoglobulins, cryoglobulins, APC resistance, protein C, S, homocysteine ANAs, ENA, anti-DNA, ANCAs, antiphospholipid antibodies, lupus antibodies, pemphigus and pemphigoid antibodies, vitamins (B12, D3, folic acid, A), trace elements (Fe, Zn, Mg, Cu) Serological tests (lues tests—TPHA, leprosis, tbc) |

VAS—visual analog scale for pain; DVT—deep-vein thrombosis; SVT—superficial-vein thrombosis; PE—pulmonary embolism; PAD—peripheral arterial disease; BMI—body mass index; CW Doppler—continuous-wave Doppler; S–F junction—saphenofemoral junction; Duplex US—duplex ultrasound; IVUS—intravascular ultrasound; CT—computed tomography; MR—magnetic resonance; HBA1c—hemoglobin A1c, glycated hemoglobin; APC—activated protein C; ANA—antinuclear antibodies; ENA—extractable nuclear antigen; anti-DNA—anti-double-stranded DNA (anti-dsDNA); ANCAs—antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; Fe—ferrum; Zn—zinc; Mg—magnesium; Cu—copper; TPHA—Treponema Pallidum Hemagglutination Assay; tbc—tuberculosis.

Table 2. Assessment of leg ulcer.

| The Questions We Ask Ourselves | The Causes/Symptoms/Signs | Tests for Making the Diagnosis |

|---|---|---|

| What is the immediate cause of the wound? |

|

|

| Is there any underlying pathology? |

|

|

| Does the patient have any (medical) conditions? | Diabetes mellitus, malnutrition, cardiovascular disease, anemia, renal disease, rheumatoid arthritis, cerebrovascular disease, old age, reduction in sensory perception, increasing susceptibility to trauma, therapy with immunosuppression agents, malignancies and their treatment, smoking, alcohol consumption, drug use, prolonged standing/sitting, obesity, poor mobility |

SF−saphenofemoral; DU—Doppler ultrasound; DVT/SVT−deep-vein thrombosis/superficial-vein thrombosis; ABI−ankle–brachial index; HBA1c—hemoglobin A1c, glycated hemoglobin; ANCAs−antineutrophil cytoplasmic antibodies; HPE−histopathological examination; DIF−direct immunofluorescence microscopy; CRP−C-reactive protein; ESR−erythrocyte sedimentation rate.

Regarding investigations, individual studies’ recommendations could be more robust [10][11] (Table 3).

Table 3. Recommendations of investigations in patients with venous leg ulcers/level of evidence.

| Palpation of lower-extremity arterial pulses and calculated ABI are recommended for all patients with suspected venous leg ulcers | C |

| Duplex ultrasound sonography is recommended for patients with venous leg ulcers to assess venous reflux and/or obstruction | C |

| Biopsy is recommended for patients with venous leg ulcers if healing stalls | C |

| Biopsy is recommended for patients with ulcers if there is suspicion that the ulcer may be venous, but it has an atypical appearance | C |

| Referral to a subspecialist is recommended for patients with venous leg ulcers if healing stalls | C |

| Referral to a subspecialist is recommended for patients with ulcers if there is suspicion that the ulcer is not venous, but it is of an atypical appearance | C |

| Screening of patients using a hand-held Doppler detector makes sense only in mild involvement when only telangiectasias and venectasias are present | C |

| X-ray contrast venography, magnetic resonance, or computed tomography venography are reasonable to perform only in a small number of selected patients who have anatomical venous anomalies, and in those patients in whom surgical intervention on the deep venous system is planned. | C |

ABI−ankle–brachial index; C−based on expert opinion and consensus guidelines in the absence of clinical trials.

VLUs are more common in patients with positive family histories of chronic venous insufficiency, in patients with higher body mass indexes, in patients with histories of pulmonary embolism or superficial-/deep-vein thrombosis, in diseases of the skeleton or joints of the lower extremities (due to poor mobility or immobility of the ankle), in women with multiple pregnancies or on hormone therapy, in those patients who have previously had ulcers, in patients who have lipodermatosclerosis and other signs of venous disease or venous insufficiency, and in patients who have typical evening swelling of the legs. Poor prognostic signs for healing are an ulcer duration longer than three months, an initial ulcer size of 10 cm or more at the start of treatment, and the presence of lower-extremity arterial disease. Patients with venous ulcers have ulcers that are usually shallow with well-defined edges and that are often located in the lower two-thirds of the lower leg. Signs of venous disease, such as varicose veins, edema, corona phlebectatica, atrophie blanche, and eczema due to stasis, may also be present. At the same time, patients should have palpable pedal pulses and a calculated brachial–ankle index above 0.85. On Duplex ultrasound, superficial and/or deep veins or perforating veins are insufficient. Severe complications include infection and malignant changes in the ulcer. All these symptoms and signs, as well as associated diseases and specifics in the anamnesis and clinical picture, as well as objections to investigations, help us diagnose venous ulcers and distinguish them from other possible causes of leg ulcers [18][19][20].

References

- Eklöf, B.; Rutherford, R.B.; Bergan, J.J.; Carpentier, P.H.; Gloviczki, P.; Kistner, R.L.; Meissner, M.H.; Moneta, G.L.; Myers, K.; Padberg, F.T.; et al. American Venous Forum International Ad Hoc Committee for Revision of the CEAP Classification. Revision of the CEAP classification for chronic venous disorders: Consensus statement. J. Vasc. Surg. 2004, 40, 1248–1252.

- Raffetto, J.D. The definition of the venous ulcer. J. Vasc. Surg. 2010, 52 (Suppl. 5), 46S–49S.

- Kahle, B.; Hermanns, H.J.; Gallenkemper, G. Evidence-based treatment of chronic leg ulcers. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2011, 108, 231–237.

- Wipke-Tevis, D.D.; Rantz, M.J.; Mehr, D.R.; Popejoy, L.; Petroski, G.; Madsen, R.; Conn, V.S.; Grando, V.T.; Porter, R.; Maas, M. Prevalence, incidence, management, and predictors of venous ulcers in the long-term-care population using the MDS. Adv. Skin Wound Care 2000, 13, 218–224.

- Kantor, J.; Margolis, D.J. A multicentre study of percentage change in venous leg ulcer area as a prognostic index of healing at 24 weeks. Br. J. Dermatol. 2000, 142, 960–964.

- Yim, E.; Richmond, N.A.; Baquerizo, K.; Van Driessche, F.; Slade, H.B.; Pieper, B.; Kirsner, R.S. The effect of ankle range of motion on venous ulcer healing rates. Wound Repair Regen. 2014, 22, 492–496.

- Vivas, A.; Lev-Tov, H.; Kirsner, R.S. Venous Leg Ulcers. Ann. Intern. Med. 2016, 165, ITC17–ITC32.

- Browse, N.L.; Burnand, K.G. The cause of venous ulceration. Lancet 1982, 2, 243–245.

- Thomas, P.R.; Nash, G.B.; Dormandy, J.A. White cell accumulation in dependent legs of patients with venous hypertension: A possible mechanism for trophic changes in the skin. Br. Med. J. (Clin. Res. Ed.) 1988, 296, 1693–1695.

- Schmid-Schönbein, G.W.; Takase, S.; Bergan, J.J. New advances in the understanding of the pathophysiology of chronic venous insufficiency. Angiology 2001, 52 (Suppl. 1), S27–S34.

- Raffetto, J.D. Inflammation in chronic venous ulcers. Phlebology 2013, 28 (Suppl. 1), 61–67.

- Raffetto, J.D. Pathophysiology of Chronic Venous Disease and Venous Ulcers. Surg. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 98, 337–347.

- Ghatnekar, G.S.; Grek, C.L.; Armstrong, D.G.; Desai, S.C.; Gourdie, R.G. The effect of a connexin43-based Peptide on the healing of chronic venous leg ulcers: A multicenter, randomized trial. J. Investig. Dermatol. 2015, 135, 289–298.

- Spoljar, S. Osnovni dijagnosticki postupci kod bolesnika s venskim ulkusom . Acta Med. Croat. 2013, 67 (Suppl. 1), 21–28.

- Himanshu, V.; Ramesh, K.T. Venous ulcer. In Ulcer of the Lower Extremity; Khanna, A.K., Tiwary, S.K., Eds.; Springer: New Delhi, India, 2016; pp. 141–162.

- Planinšek Ručigaj, T. Diseases of the veins and arteries (leg ulcers), chronic wounds, and their treatment. In Atlas of Dermatology, Dermatopathology and Venereology: Inflammatory Dermatoses; Smoller, B.R., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 1205–1331. ISBN 9783319538044.

- Morison, M.J.; Moffat, C.J. A framework for patient assessment and care planning. In Leg Ulcers: A Problem-Based Learning Approach; Morison, M.J., Moffat, C.J., Franks, P.J., Eds.; Mosby, Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2007; pp. 119–139.

- Bonkemeyer Millan, S.; Gan, R.; Townsend, P.E. Venous Ulcers: Diagnosis and Treatment. Am. Fam. Physician 2019, 100, 298–305.

- Kecelj, N.; Kozak, M.; Slana, A.; Šmuc Berger, K.; Šikovec, A.; Makovec, M.; Blinc, A.; Žuran, I.; Planinšek Ručigaj, T. Recommendations of the diagnosis and treatment of chronic venous disease. Zdr. Vestn. Glas. Slov. Zdr. Društva 2017, 86, 345–361.

- Srisuwan, T.; Inmutto, N.; Kattipathanapong, T.; Rerkasem, A.; Rerkasem, K. Ultrasound Use in Diagnosis and Management of Venous Leg Ulcer. Int. J. Low. Extrem. Wounds 2020, 19, 305–314.

More

Information

Subjects:

Peripheral Vascular Disease

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

987

Revisions:

3 times

(View History)

Update Date:

26 Sep 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No