| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Alice Vilela | -- | 2947 | 2023-09-12 13:33:59 | | | |

| 2 | Peter Tang | Meta information modification | 2947 | 2023-09-13 04:36:01 | | |

Video Upload Options

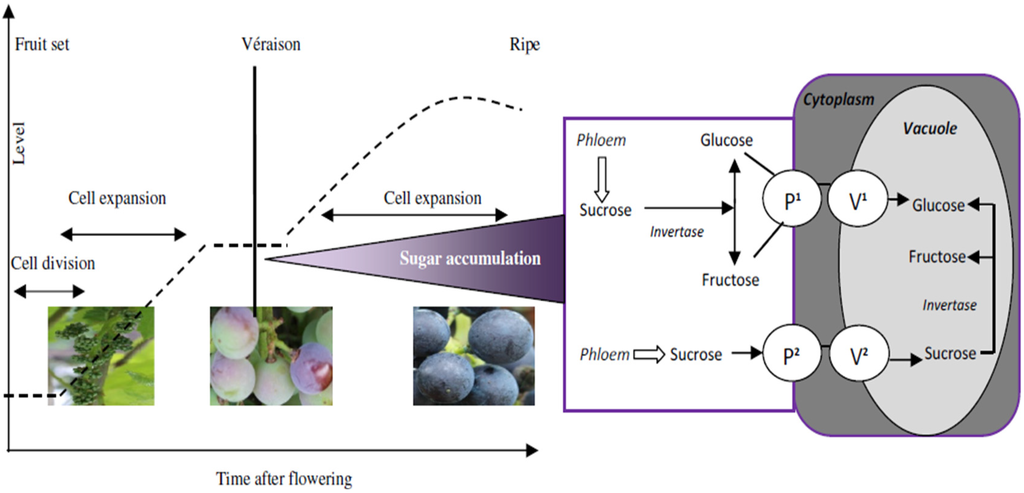

The quality of grapes and wine quality, flavor, stability, and sensory characteristics depend on the content and composition of several different groups of compounds from grapes. One of these groups of compounds is sugars and, consequently, the alcohol content quantified in wines after alcoholic fermentation. During grape berry ripening, sucrose transported from the leaves is accumulated in the berry vacuoles as glucose and fructose. The wine alcohol content continues to be a challenge in enology, as it is also the study of the role of chemosensory factors in alcohol intake and consumer preferences. Several technical and scientific advances have occurred, such as identifying receptors and other essential molecules involved in the transduction mechanisms of flavor. In addition, consumers know that wines with high alcohol content can cause a gustatory disequilibrium affecting wine sensory perceptions, leading to unbalanced wines.

1. General Introduction

2. Grape Berry Composition—Sugars

3. Sugar Accumulation during Grape Ripening

4. Factors that Affect the Sugar Accumulation and Level in Grape Berries

5. Psychophysiology of Alcohol Perception

6. The Effects of Ethanol on the Body and Other Sensory Characteristics of Wines

References

- Goldner, M.C.; Zamora, M.C.; di Leo Lira, P.; Gianninoto, H.; Bandoni, A. Effect of ethanol level in the perception of aroma attributes and the detection of volatile compounds in red wine. J. Sens. Stud. 2009, 24, 243–257.

- Fontoin, H.; Saucier, C.; Teissedre, P.L.; Glories, Y. Effect of pH, ethanol and acidity on astringency and bitterness of grape seed tannin oligomers in model wine solution. Food Qual. Preference 2008, 19, 286–291.

- Meillon, S.; Urbano, C.; Schlich, P. Contribution of the temporal dominance of sensations (TDS) method to the sensory description of subtle differences in partially dealcoholized red wines. Food Qual. Preference 2009, 20, 490–499.

- Pickering, G.J.; Heatherbell, D.A.; Vanhanen, L.P.; Barnes, M.F. The effect of ethanol concentration on the temporal perception of viscosity and density in white wine. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1998, 49, 306–318.

- Fischer, U.; Noble, A.C. The effect of ethanol, catechin concentration, and pH on sourness and bitterness of wine. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1994, 45, 6–10.

- Jones, G.V.; White, M.A.; Cooper, O.R.; Storchmann, K. Climate change and global wine quality. Clim. Chang. 2005, 73, 319–343.

- Koufos, G.; Mavromatis, T.; Koundouras, S.; Fyllasd, N.M.; Jones, G.V. Viticulture-climate relationships in Greece: The impacts of recent climate trends on harvest date variation. Int. J. Climatol. 2013, 34, 1445–1459.

- Labanda, J.; Vichi, S.; Llorens, J.; López-Tamames, E. Membrane separation technology for the reduction of alcoholic degree of a white model wine. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2009, 42, 1390–1395.

- Masson, J.; Aurier, P.; D’hauteville, F. Effects of non-sensory cues on perceived quality: The case of low-alcohol wine. Int. J. Wine Bus. Res. 2008, 20, 215–229.

- Saliba, A.J.; Ovington, L.A.; Moran, C.C. Consumer demand for low-alcohol wine in an Australian sample. Int. J. Wine Res. 2013, 5, 1–8.

- Szczesniak, A.S. Classification of mouthfeel characteristics of beverages. In Food Rheology and Texture; Sherman, P., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 1979; pp. 1–20.

- Szczesniak, A.S. Psychorheology and texture as factors controlling the consumer acceptance of food. Cereal Foods World 1990, 35, 1201–1205.

- Noble, A.C.; Arnold, R.A.; Buechsenstein, J.; Leach, E.J.; Schmidt, J.O.; Stern, P.M. Modification of a standardized system of wine aroma terminology. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1987, 38, 143–146.

- Smith, A.K.; June, H.; Noble, A.C. Effects of viscosity on the bitterness and astringency of grape seed tannin. Food Qual. Preference 1996, 7, 161–166.

- Hollowood, T.A.; Linforth, R.S.T.; Taylor, A.J. The effect of viscosity on the perception of flavour. Chem. Senses 2002, 27, 583–589.

- Yanniotis, S.; Kotseridis, G.; Orfanidou, A.; Petraki, A. Effect of ethanol, dry extract and glycerol on the viscosity of wine. J. Food Eng. 2007, 81, 399–403.

- Da Porto, C.; Cordaro, F.; Marcassa, N. Effects of carbohydrate and noncarbohydrate sweeteners on the orange spirit volatile compounds. Food Sci. Technol. 2006, 39, 159–165.

- Walker, S.; Prescott, J. The influence of solution viscosity and different viscosifying agents of apple juice flavour. J. Sens. Stud. 2000, 15, 285–307.

- Dalton, P.; Doolittle, N.; Nagata, H.; Breslin, P.A.S. The merging of the senses: Integration of subthreshold taste and smell. Nat. Neurosci. 2000, 3, 431–432.

- Cichero, J.A.Y.; Jackson, O.J.; Halley, P.J.; Murdoch, B.E. How thick is thick? Multicenter study of the rheological and material property characteristics of meal time fluids and videofluoroscopy fluids. Dysphagia 2000, 15, 188–200.

- Pankiewicz, U.; Jamroz, J. Evaluation of Physicochemical and Sensory Properties of Ethanol Blended with Pear Nectar. Czech J. Food Sci. 2013, 31, 66–71.

- Carroll, D.E.; Hoover, M.W.; Nesbitt, W.B. Sugar and organic acid concentrations in cultivars of muscadine grapes. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1971, 96, 737–740.

- Shiraishi, M. Three descriptors for sugars to evaluate grape germplasm. Euphytica 1993, 71, 99–106.

- Dai, Z.W.; Ollat, N.; Gomès, E.; Decroocq, S.; Tandonnet, J.-P.; Bordenave, L.; Pieri, P.; Hilbert, G.; Kappel, C.; van Leeuwen, C.; et al. Ecophysiological, genetic, and molecular causes of variation in grape berry weight and composition: A review. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2011, 62, 413–425.

- Shiraishi, M.; Fujishima, H.; Chijiwa, H. Evaluation of table grape genetic resources for sugar, organic acid, and amino acid composition of berries. Euphytica 2010, 174, 1–13.

- Liu, H.F.; Wu, B.H.; Fan, P.G.; Li, S.H.; Li, L.S. Sugar and acid concentrations in 98 grape cultivars analyzed by principal component analysis. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2006, 86, 1526–1536.

- Conde, B.C.; Silva, P.; Fontes, N.; Dias, A.C.P.; Tavares, R.M.; Sousa, M.J.; Agasse, A.; Delrot, S.; Geros, H. Biochemical changes throughout grape berry development and fruit and wine quality. Food 2007, 1, 1–22.

- Boss, P.K.; Davies, C. Molecular biology of sugar and anthocyanin accumulation in grape berries. In Molecular Biology and Biotechnology of the Grapevine; Roubelakis-Angelakis, K.A, Ed.; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2001; pp. 1–33.

- Williams, L.E.; Lemoine, R.; Sauer, N. Sugar transporters in higher plants—A diversity of roles and complex regulation. Trends Plant Sci. 2000, 5, 283–290.

- Robinson, S.P.; Davies, C. Molecular biology of grape berry ripening. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2000, 6, 175–188.

- Coombe, B.G. Research on Development and Ripening of the Grape Berry. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1992, 43, 101–110.

- Fillion, L.; Ageorges, A.; Picaud, S.; Coutos-Thevenot, P.; Lemoine, R.; Romieu, C.; Delrot, S. Cloning and expression of a hexose transporter gene expressed during the ripening of grape berry. Plant Physiol. 1999, 120, 1083–1093.

- Hawker, J.S. Changes in the activities of enzymes concerned with sugar metabolism during the development of grape berries. Phytochemistry 1969, 8, 9–17.

- Kühn, C.; Franceschi, V.R.; Schulz, A.; Lemoine, R.; Frommer, W.B. Macromolecular trafficking indicated by localization and turnover of sucrose transporters in enucleate sieve elements. Science 1997, 275, 1298–1300.

- Delrot, S.; Atanassova, R.; Maurousset, L. Regulation of sugar, amino acid and peptide plant membrane transporters. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2000, 1465, 281–306.

- Octave, S.; Emborabé, B.E.; Fleurat-Lessard, P.; Bergès, T.; Roblin, G. Modifications of plant cell activities by polypeptides secreted by Eutypa lata, a vineyard fungal pathogen. Physiol. Plant. 2006, 128, 103–115.

- Esteban, M.A.; Villanueva, M.J.; Lissarrague, J.R. Relalationships between different berry components in Tempranillo (Vitis vinifera L.) grapes from irrigated and non-irrigated vines during ripening. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2002, 82, 1136–1146.

- Jordão, A.M.; Ricardo-da-Silva, J.M.; Laureano, O. Influência da rega na composição fenólica das uvas tintas da casta Touriga Francesa (Vitis vinifera L.). Cienc. Tecnol. Aliment. 1998, 2, 60–73.

- Esteban, M.A.; Villanueva, M.J.; Lissarrague, J.R. Effect of Irrigation on Changes in Berry Composition of Tempranillo during Maturation. Sugars, Organic Acids, and Mineral Elements. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 1999, 50, 418–434.

- Orts, M.L.; Martínez-Cutillas, A.; López-Roca, J.M.; Gómez-Plaza, E. Effect of moderate irrigation on grape composition during ripening. J. Agric. Res. 2005, 3, 352–361.

- Intrigliolo, D.S.; Castel, J.R. Effects of Irrigation on the Performance of Grapevine cv. Tempranillo in Requena. Am. J. Enol. Vitic. 2008, 59, 30–38.

- Van Leeuwen, C.; Tregoat, O.; Choné, X.; Bois, B.; Pernet, D.; Gaudillère, J.-P. Vine water status is a key factor in grape ripening and vintage quality for red bordeaux wine. How can it be assessed for vineyard management purposes? J. Int. Sci. Vigne Vin. 2009, 43, 121–134.

- Hawker, J.S. Effect of temperature on lipid, starch and enzymes of starch metabolism in grape, tomato and broad bean-leaves. Phytochemistry 1982, 21, 33–36.

- De Orduña, R. Climate change associated effects on grape and wine quality and production. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 1844–1855.

- Huglin, P.; Schneider, C. Biologie et Ecologie de la Vigne; Tec & Doc Lavoisier: Commune, France, 1998.

- Kriedemann, P.; Smart, R. Effect of irradiance, temperature and leaf water potential on photosynthesis of vine leaves. Photosynthetica 1971, 5, 6–15.

- Coombe, B. Influence of temperature on composition and quality of grapes. In ISHS Acta Horticulturae, Proceedings of the International Symposium on Grapevine Canopy and Vigor Management, Davis, CA, USA, 14 August 1986; Volume XXII IHC, pp. 23–35.

- Keller, M. Managing grapevines to optimise fruit development in a challenging environment: A climate change primer for viticulturists. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2009, 16, 56–69.

- Keller, M. The Science of Grapevines: Anatomy and Physiology; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 2010.

- García-Martín, N.; Perez-Magariño, S.; Ortega-Heras, M.; González-Huerta, C.; Mihnea, M.; González-Sanjosé, M.L.; Palacio, L.; Prádanos, P.; Hernández, A. Sugar reduction in musts with nanofiltration membranes to obtain low alcohol-content wines. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2010, 76, 158–170.

- Castellarin, S.; Matthews, M.; Gaspero, G.; Gambetta, G. Water deficits accelerate ripening and induce changes in gene expression regulating flavonoid biosynthesis in grape berries. Planta 2007, 227, 101–112.

- Berli, F.J.; Moreno, D.; Piccoli, P.; Hespanhol-Viana, L.; Silva, M.F.; Bressan-Smith, R.; Cavagnaro, J.B.; Bottini, R. Abscisic acid is involved in the response of grape (Vitis vinifera L.) cv. Malbec leaf tissues to ultraviolet-B radiation by enhancing ultraviolet-absorbing compounds, antioxidant enzymes and membrane sterols. Plant Cell Environ. 2010, 33, 1–10.

- Duchêne, E.; Schneider, C. Grapevine and climatic changes: A glance at the situation in Alsace. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2005, 24, 93–99.

- Godden, P.; Gishen, M. Trends in the composition of Australian wine. Aust. N. Z. Wine Ind. J. 2005, 20, 21–46.

- Glanz, K.; Basil, M.; Maibach, E.; Goldberg, J.; Snyder, D. Why Americans eat what they do: Taste, nutrition, cost, convenience, and weight control concerns as influences on food consumption. J. Am. Diet. Assoc. 1998, 98, 1118–1126.

- Moore, M.; Weiss, S. Reasons for non-drinking among Israeli adolescents of four religions. Drug Alcohol Depend. 1995, 38, 45–50.

- Higgs, S.; Stafford, L.D.; Attwood, A.S.; Walker, S.C.; Terry, P. Cues that signal the alcohol content of a beverage and their effectiveness at altering drinking rates in young social drinkers. Alcohol Alcohol. 2008, 43, 630–635.

- Lanier, S.A.; Hayes, J.E.; Duffy, V.B. Sweet and bitter tastes of alcoholic beverages mediate alcohol intake in of-age undergraduates. Physiol. Behav. 2005, 83, 821–831.

- Bartoshuk, L.M.; Conner, E.; Grubin, D.; Karrer, T.; Kochenbach, K.; Palsco, M.; Snow, D.; Pelchat, M.; Danovski, S. PROP supertasters and the perception of ethyl alcohol. Chem. Senses 1993, 18, 526–527.

- Mattes, R.D.; DiMeglio, D. Ethanol perception and ingestion. Physiol. Behav. 2001, 72, 217–229.

- Wooding, S.; Kim, U.K.; Bamshad, M.J.; Larsen, J.; Jorde, L.B.; Drayna, D. Natural Selection and Molecular Evolution in PTC, a Bitter-Taste Receptor Gene. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 2004, 74, 637–646.

- Drayna, D.; Coon, H.; Kim, U.K.; Elsner, T.; Cromer, K.; Otterud, B.; Baird, L.; Peiffer, A.P.; Leppert, M. Genetic analysis of a complex trait in the Utah Genetic Reference Project: A major locus for PTC taste ability on chromosome 7q and a secondary locus on chromosome 16p. Hum. Genet. 2003, 112, 567–572.

- Kim, U.K.; Jorgenson, E.; Coon, H.; Leppert, M.; Risch, N.; Drayna, D. Positional cloning of the human quantitative trait locus underlying taste sensitivity to phenylthiocarbamide. Science 2003, 299, 1221–1225.

- Duffy, V.B.; Davidson, A.C.; Kidd, J.R.; Kidd, K.K.; Speed, W.C.; Pakstis, A.J.; Reed, D.R.; Snyder, D.J.; Bartoshuk, L.M. Bitter receptor gene (TAS2R38), 6-n-propylthiouracil (PROP) bitterness and alcohol intake. Alcohol. Clin. Exp. Res. 2004, 28, 1629–1637.

- Dotson, C.D.; Wallace, M.R.; Bartoshuk, L.M.; Logan, H.L. Variation in the gene TAS2R13 is associated with differences in alcohol consumption in patients with head and neck cancer. Chem. Senses 2012, 37, 737–744.

- Tominaga, M.; Caterina, M.J.; Malmberg, A.B.; Rosen, T.A.; Gilbert, H.; Skinner, K.; Raumann, B.E.; Basbaum, A.I.; Julius, D. The cloned capsaicin receptor integrates multiple pain-producing stimuli. Neuron 1998, 21, 531–543.

- Caterina, M.J.; Rosen, T.A.; Tominaga, M.; Brake, A.J.; Julius, D. A capsaicin-receptor homologue with a high threshold for noxious heat. Nature 1999, 398, 436–441.

- Trevisani, M.; Smart, D.; Gunthorpe, M.J.; Tognetto, M.; Barbieri, M.; Campi, B.; Amadesi, S.; Gray, J.; Jerman, J.C.; Brough, S.J.; et al. Ethanol elicits and potentiates nociceptor responses via the vanilloid receptor-1. Nat. Neurosci. 2002, 5, 546–551.

- Blednov, Y.; Harris, R. Deletion of vanilloid receptor (TRPV1) in mice alters behavioral effects of ethanol. Neuropharmacology 2009, 56, 814–820.

- Ferraro, F.M.; Hill, K.G.; Kaczmarek, H.J.; Coonfield, D.L.; Kiefer, S.W. Naltrexone modifies the palatability of basic tastes and alcohol in outbred male rats. Alcohol 2002, 27, 107–114.

- Mennella, J.A. The transfer of alcohol to human milk: Sensory implications and effects on mother-infant interaction. In Alcohol and Alcoholism: Brain and Development; Spear, N.E., Spear, L.P., Hanningan, J.H., Goodlett, C.R., Eds.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1999; pp. 177–198.

- Molina, J.C.; Domínguez, H.D.; López, M.F.; Pepino, M.Y.; Faas, A.E. The role of fetal and infantile experience with alcohol in later recognition and acceptance patterns of the drug. In Alcohol and Alcoholism: Brain and Development; Spear, N.E., Spear, L.P., Hanningan, J.H., Goodlett, C.R., Eds.; Erlbaum: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1999; pp. 199–228.

- Buck, L.; Axel, R. A novel multigene family may encode odourant receptors: A molecular basis for odour recognition. Cell 1991, 65, 175–187.

- Menco, B.P.; Morrison, E.E. Morphology of the mammalian olfactory epithelium: Form, fine structure, function, and pathology. In Handbook of Olfaction and Gustation; Doty, R., Ed.; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 2003; pp. 17–49.

- Caterina, M.J.; Schumacher, M.A.; Tominaga, M.; Rosen, T.A.; Levine, J.D.; Julius, D. The capsaicin receptor: A heat-activated ion channel in the pain pathway. Nature 1997, 389, 816–824.

- Li, X.; Staszewski, L.; Xu, H.; Durick, K.; Zoller, M.; Adler, E. Human receptors for sweet and umami taste. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 4692–4696.

- Nelson, G.; Hoon, M.A.; Chandrashekar, J.; Zhang, Y.; Ryba, N.J.; Zuker, C.S. Mammalian sweet taste receptors. Cell 2001, 106, 381–390.

- Nelson, G.; Chandrashekar, J.; Hoon, M.A.; Feng, L.; Zhao, G.; Ryba, N.J.; Zuker, C.S. An amino-acid taste receptor. Nature 2002, 416, 199–202.

- Margolskee, R.F. Molecular mechanisms of taste transduction. Pure Appl. Chem. 2002, 74, 1125–1133.

- Gawel, R.; van sluyter, S.; Waters, E.J. The effects of ethanol and glycerol on the body and other sensory characteristics of Riesling wines. Aust. J. Grape Wine Res. 2007, 13, 38–45.

- Gawel, R. The use of language by trained and untrained experienced wine tasters. J. Sens. Stud. 1997, 12, 267–284.

- Amerine, M.A.; Roessler, E.B. Wines: Their Sensory Evaluation; Freeman, W.H., Ed.; W. H. Freeman & Co.: San Francisco, CA, USA, 1983.

- Nurgel, C.; Pickering, G. Contribution of glycerol, ethanol and sugar to the perception of viscosity and density elicited by model white wines. J. Texture Stud. 2005, 36, 303–325.

- Guth, H.; Sies, A. Flavour of wines: Towards an understanding by reconstitution experiments and an analysis of ethanol’s effect on odour activity of key components. In Proceedings of the Eleventh Australian Wine Industry Technical Conference, Adelaide, Australia, 7–11 October 2001; Australian Wine Industry Technical Conference Inc.: Adelaide, Australia, 2002; pp. 128–139.

- Scinska, A.; Koros, E.; Habrat, B.; Kukwa, A.; Kostowski, W.; Bienkowski, P. Bitter and sweet components of ethanol taste in humans. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2000, 60, 199–206.

- Joshi, V.K.; Sandhu, D.K. Influence of Ethanol Concentration, Addition of Spices Extract, and Level of Sweetness on Physico-chemical Characteristics and Sensory Quality of Apple Vermouth. Braz. Arch. Biol. Technol. 2000, 43, 537–545.

- Noble, A.C. Why Do Wines Taste Bitter and Feel Astringent? In Chemistry of Wine Flavour; Waterhouse, A.L., Ebeler, S.E., Eds.; American Chemical Society: Washington, DC, USA, 1998; pp. 156–165.