Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Estibaliz Sansinenea | -- | 2116 | 2023-09-05 15:42:34 | | | |

| 2 | Jessie Wu | Meta information modification | 2116 | 2023-09-06 05:42:18 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Ortiz, A.; Sansinenea, E. Genetic Engineering in Bacillus . Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/48833 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Ortiz A, Sansinenea E. Genetic Engineering in Bacillus . Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/48833. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Ortiz, Aurelio, Estibaliz Sansinenea. "Genetic Engineering in Bacillus " Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/48833 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Ortiz, A., & Sansinenea, E. (2023, September 05). Genetic Engineering in Bacillus . In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/48833

Ortiz, Aurelio and Estibaliz Sansinenea. "Genetic Engineering in Bacillus ." Encyclopedia. Web. 05 September, 2023.

Copy Citation

Due to the increase in the global population, there is an urgent call to enhance the crop production through sustainable agriculture. Biological control is a possible solution. There are many examples of biological control agents applied to different crops that have improved their yield or quality, including vegetable and fruit crops and ornamental plants. The Bacillus species have been used as powerful tools since they suppress plant pathogens and promote plant growth as well. B. thuringiensis has been used as biopesticide in several crops.

antifungals

biofungicides

biopesticides

1. Bacillus in Horticultural Crops

The horticultural sector improves land use for food and promotes crop diversification, employment generation and poverty alleviation. Among the horticultural crops, fruits and vegetables are the most numerous crops; however, there are also flowers, aromatic plants, spices, and plantation crops. There are many examples of different crops that improved their yield or quality after the application of a biological control agent, including vegetable, fruit, and ornamental plants [1].

One of the most important aspects of achieving the good quality and yield of horticultural crop production is the availability of nutrients in the soil. For this reason, over the years, chemical fertilizers have played the main role in increasing the productivity of crops. This practice has led to several problems, such as environmental pollution and therefore impacts on human health. The best green alternative has been the development of biofertilizers, which are supported by microorganisms that are nitrogen fixers, solubilizers of phosphates, and phytohormones and growth promoters. All of them use different strategies to facilitate plant growth. Biofertilizers have been evaluated in a wide variety of crops, including rice, cucumber, wheat, sugarcane, and corn, among others [2]. The application of biofertilizers in horticulture implies the improvement of the yield and quality of crops. Beneficial microorganisms improve the rhizospheric region, making nutrients available for plants or producing phytohormones.

Bacillus spp. use direct and indirect mechanisms that can act simultaneously in plant growth. The direct mechanisms include achievement of nutrient supplies and modulation of plant hormone levels. The indirect mechanisms include the secretion of chemical compounds to act against phytopathogens or the induction of pathogen resistance [3].

There are several examples of the role of Bacillus as a biofertilizer. Among vegetables, some examples are included. The yield of mustard and tomato was increased after applying Bacillus- or Trichoderma-based fertilizers [4][5]. By applying individual inoculants of Bacillus, Brevibacillus, and Rhizobium, the macro- and micronutrient content in broccoli was improved [6]. Bacillus and Pseudomonas improved the biomass of lettuce seedlings [7]. Similarly, other crops such as spinach and flax, also exhibited improvements after treatment with Azotobacter, Bacillus, or AMF [8][9]. B. subtilis was applied as a biofertilizer to increase cotton yield [10]. Treatment with B. subtilis and B. megaterium resulted in growth and yield increasement, and improved seed quality of maize [11].

Bacillus strains have been intensively used against Fusarium [12][13][14][15][16] and Aspergillus [17][18][19] species. Also, Bacillus-based biocontrol has been used to decrease mycotoxin contamination in crops [20][21][22]. The studies devoted to lower mycotoxin content in GM-Bt plants (maize) [23][24][25] should also be mentioned.

Generally, fruit crops have received more attention than vegetables and ornamental crops. The application of Bacillus strains has reduced the crop maturation days of strawberry plants [26]. The inoculation with the commercial product Rhizocell C containing B. amyloliquefaciens improved the photosynthetic capacity of strawberry plants, increasing the fruit yield and biomass compared to other commercialized products [27]. The inoculation with B. amyloliquefaciens has improved the yield of banana, infested with the fungal disease, under field conditions [28]. A liquid B. subtilis commercial microbial fertilizer was applied to citrus groves of the Tarocco blood orange (Citrus sinensis), exerting positive effects on fruit quality [29]. Bacillus spp. was applied as a biofertilizer to treat nutmeg seeds, showing an improvement in the growth of nutmeg seedlings [30].

Bacillus species also use indirect mechanisms to inhibit plant pathogens. The genus Bacillus spp. secretes several secondary metabolites that act against phytopathogens causing plant diseases, promoting plant growth [31][32][33][34]. In addition, these bacteria induce systemic resistance in plants [35]. There are some mechanisms to control pathogens causing plant diseases. Some of these mechanisms include (a) competition; (b) antibiosis; (c) predation or parasitism; and (d) induction of host plant resistance [36].

Biofungicides have several advantages in use against the crop pests compared with chemical pesticides. The first is that they have a strong selectivity, being safe for humans and animals. Second, they are safe for the environment since they are derived from natural ecosystems. Moreover, they are easily decomposed by sunlight, plants, or various soil microorganisms, completing a natural life cycle. This guarantees that these products do not persist long in the environment, which reduces the risk to non-target organisms [34]. Bacillus-based biopesticides control crop pests, improving soil quality and health, and the growth, yield, and quality of crops [37].

B. thuringiensis (Bt) has been the most used and commercialized biopesticide [38]. It has been widely used in agriculture since it is eco-friendly and safe for non-target organisms, but it is effective and highly specific against insect pests affecting crops belonging to the Lepidopteran, Dipteran, and Coleopteran insect orders [38]. Many commercial products of Bt bioinsecticides have been developed over the decades and are available on the market [39]. This biopesticide capacity is due to the production of crystalline proteins called Cry proteins along with spores during the sporulation stage, which are toxic to different insect orders. This capacity of Bt is important to the application of this bacterium as a green biopesticide against crop pests.

2. Genetic Engineering in Bacillus Applied to Plants

Genetic engineering is a method of making changes to the genetic material of an organism using scientific techniques. Genetic engineering has become an intervention in the field of agricultural and industrial biotechnology including different types of plants, animals, and microorganisms [40]. In agriculture, these techniques have been applied to achieve modified crops by integrating sequences of DNA into the germplasm of crop plants to obtain new crops with better characteristics than wild-type crops, such as appearance, yield, size, and resistance to pests. The integrated DNA sequences encode insecticidal proteins in transgenic plants to resist insect pests [41].

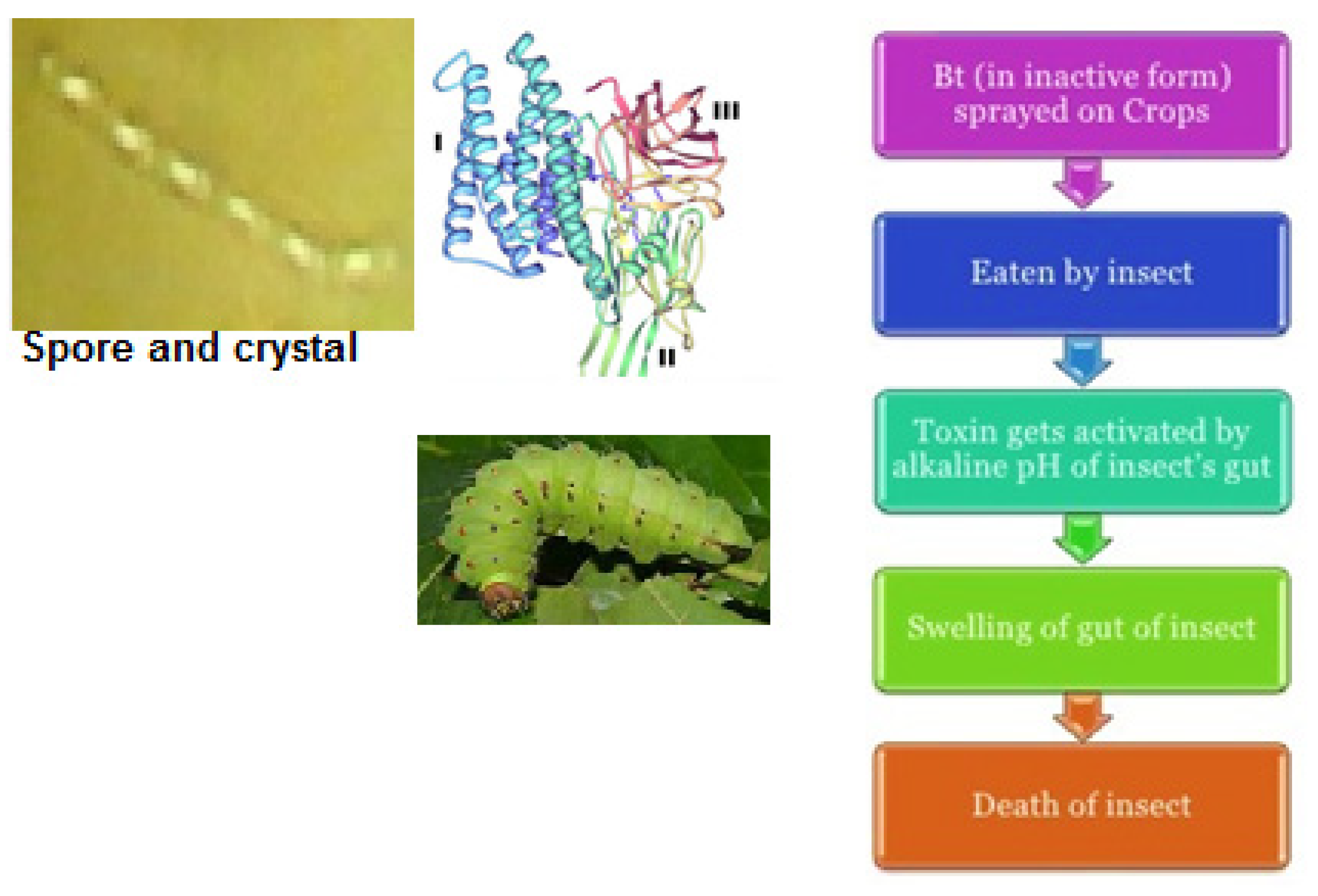

To understand how B. thuringiensis was genetically modified for introduction into several crops for pest control, it is necessary to know how this bacterium acts against several pests through its insecticidal proteins derived from toxin genes. The mechanism of action of insecticidal toxins is basically described in Figure 1. Briefly, the insecticidal toxins of B. thuringiensis need to be ingested by the insect larvae to be effective [42]. After ingestion, the toxins are solubilized by the alkaline conditions and then are converted into toxic core fragments, which bind to the receptors of epithelial midgut cells. Then, the toxin adopts a specific conformation allowing its insertion into the cell membrane and forming transmembrane pores, which cause an osmotic imbalance causing cell rupture. This leads to insect death caused by bacteremia [43].

Figure 1. Cry toxins and their mode of action in insect larvae.

These insecticidal toxins are derived from cry genes [44], which have been classified and organized in a systematic nomenclature. Cry toxins have been effective for the control of several insect pests affecting important crops. Naturally occurring cry genes and several mutations show varied specificity and novel/improved toxicity against a specific insect group. However, some insects can acquire resistance to the cry gene product [43]. Traits of Bt, such as pest resistance and herbicide properties, are most extensively used in plant genetic engineering. Bt toxin genes have been used in genetic engineering for application to many crops to act against specific pests [45]. For several years, the development of new toxin genes in new Bt strains was the main aim of researchers on this topic. After the toxin mechanism of action was studied and elucidated, research centered on altering the amino acids of the main domains of toxin. In this way, new proteins could be created.

Bt biopesticides have some advantages, such as specificity and their environmental safety and they are cheap and easily formulated [46]. However, they can have some disadvantages, such as their instability under field conditions due to sunlight; therefore, frequent applications are necessary, making their use more expensive. As has been seen, short persistence and low residual activity are two factors limiting the wide use of Bt products. Different formulations and strategies have been developed to protect Bt biopesticides from sunlight [47].

Another problem is their restricted field application since they have been applied mainly to the aerial parts of the plant. To solve this problem, genetically modified crops have been employed to allow the plant to express the toxin throughout the plant. These transgenic Bt crops are protected from insect attack by expressing Bt toxins in plant tissues. During decades of improvement of B. thuringiensis strains as biopesticides, the main issue has been their application to crops. For this reason, cry genes were manipulated to achieve genes with a wider target spectrum or higher toxicity than wild-type strains [44][48][49]. Therefore, several genetic tools were developed.

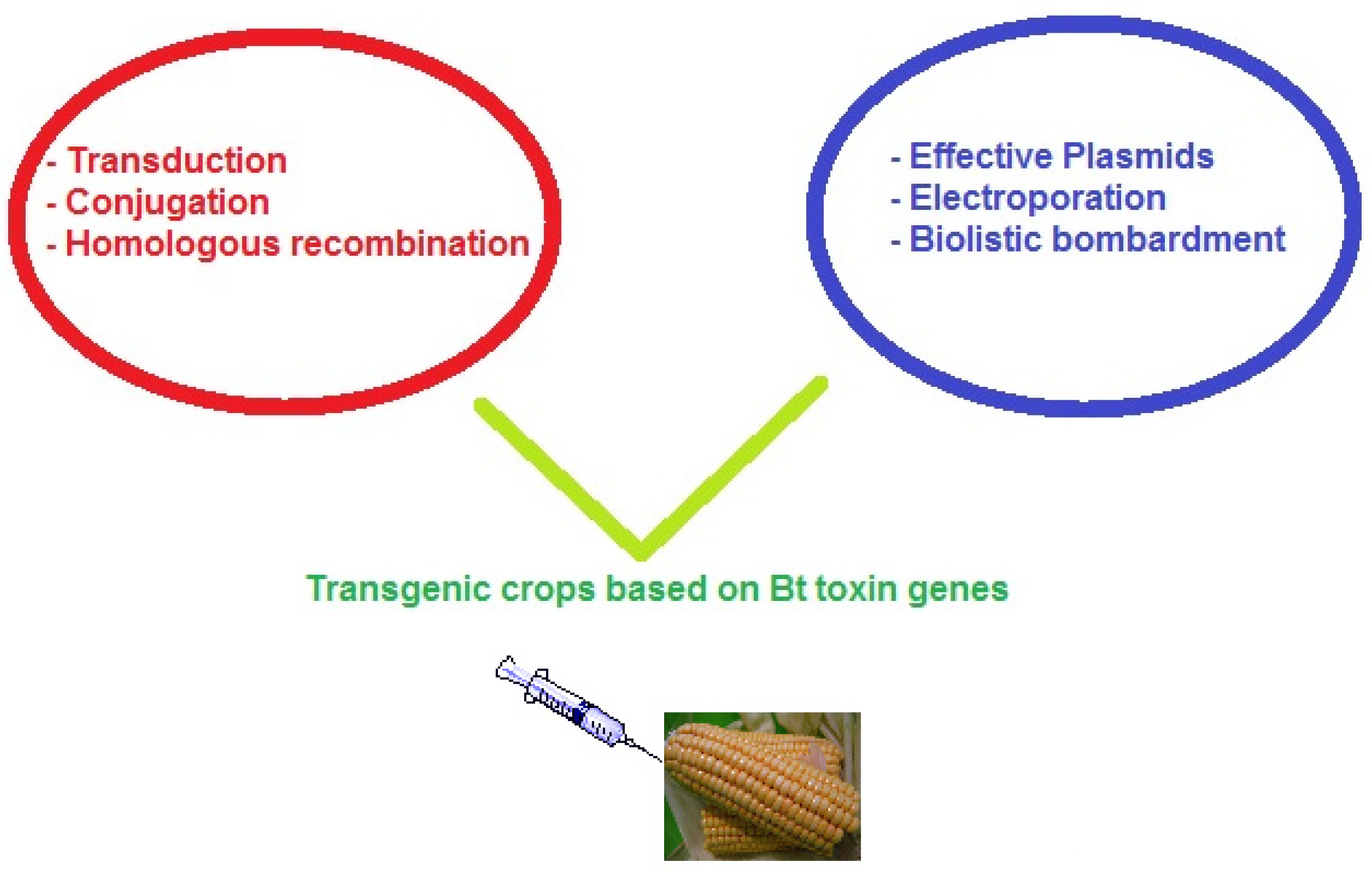

The first genetic exchange system available in B. thuringiensis was generalized transduction [50]. The second important advance in genetic exchange was the discovery of a conjugation-like process involving plasmid transfer. This tool permitted the development of strains with crystal protein gene combinations that are active against some insect species. The transfer of recombinant plasmids was possible from one strain to another. However, this technique has some limitations such as plasmid incompatibility, location of cry genes on non-transmissible plasmids, the presence of undesirable genetic material, and eventual plasmid loss [51]. Using the molecular method of in vivo homologous recombination, this structural instability or loss of plasmids can be avoided. Homologous recombination utilizes integrational vectors and thermosensitive plasmids along with chromosome fragments. These fragments are homologous to the B. thuringiensis chromosome and are introduced into the integrative plasmids to realize recombination with the chromosome. When the transformation does not occur naturally, alternative methods such as electroporation and biolistic bombardment have been effectively used on Bt transgenic crops (Figure 2). Plant expression systems such as cauliflower mosaic virus 35S promoter, maize promoter, or chloroplast promoter, were the key to expressing Bt genes in plants [52][53]. Effective promoters and expression cassettes probably could improve gene expression instead of “transformation” methods.

Figure 2. Genetic engineering strategies to achieve Bt crops.

The best option to avoid plant toxicity is to transform truncated toxin genes. For this reason, truncated cry1A genes have been used to achieve transgenic tomato, tobacco, and cotton. Several companies, such as Monsanto or Mycogen, have made several probes changing the promoters, antibiotic resistance genes, transformation-tissue culture systems, and developing novel insecticidal proteins [54]. In this way, some genetically modified products were sold by several companies, such as Ecogen. New Leaf was the variety of potato expressing the cry3A toxin gene. This was the first commercially available product of its kind, manufactured in 1995 by an affiliate of Monsanto (NatureMark) [54]. After this, other transgenic Bt crops were commercialized, including maize and cotton [55][56]. Some crops like potato, tomato, tobacco, rice, maize, and broccoli have been genetically modified to express cry genes to kill the pests causing damage to the plant. This caused great controversy about their safety for human health [57].

Similarly, genetically modified organisms, generated via transfection of B. thuringiensis subspecies genes, produce biotechnological products that have various applications. B. thuringiensis var. kurstaki (Btk) is a bacterium, which protects crops from insect pathogens and is available as a registered formulation in the marketplace (DiPel and Forey). These two formulations are applied by spraying crops in agriculture, horticulture, and woodland plants. Moreover, the insect and fungal pathogen, B. thuringiensis subsp. israelensis (Bti), is a biologically active strain that acts against mosquito species but is harmless to humans [57]. Therefore, Bti is employed for the effective treatment of stagnant ditches, ponds, lakes, and wastewater settling tanks.

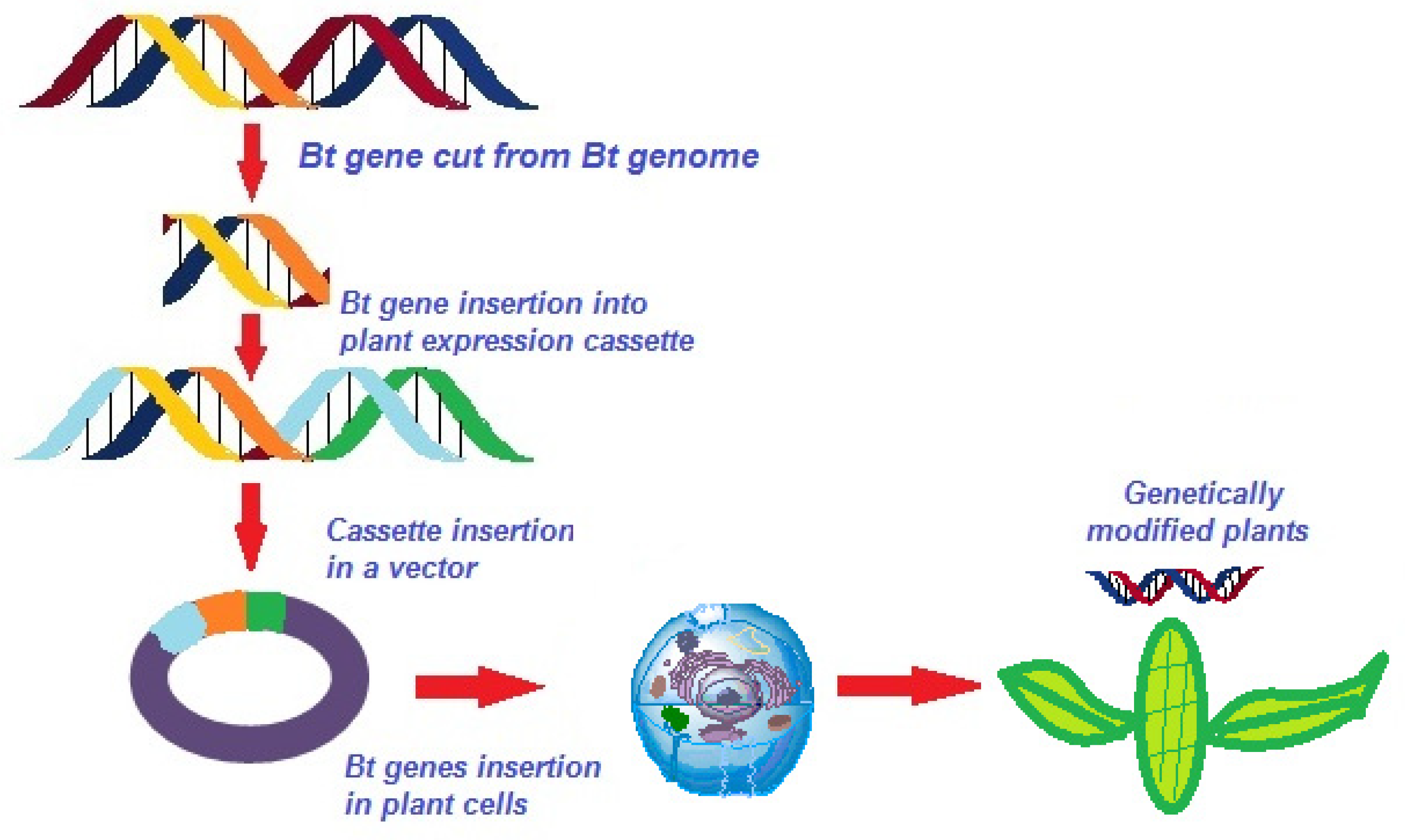

Corn expressing Cry1Ab and cotton expressing Cry1Ac are other genetically modified crops [58]. Transgenic crop cultivation expressing the insecticidal cry gene derived from B. thuringiensis, the most successful bioinsecticide, is now a common practice worldwide [59]. These transgenic plants include cotton, cauliflower, tomato, corn, chilli, and eggplants, products famous for their resistance against insects [60]. Two toxins, Cry1Ac and Cry2Ab, have been commercialized for the cotton crop with the name of Bollgard II, protecting against lepidopteran pests [61]. Another strategy was to produce GM crops with several different genes active against different target insect pests such as Monsanto’s YieldGard Plus maize expressing cry1Ab1, which is active against lepidopteran insects, and the cry3Bb1 gene, active against the coleopteran corn borer pest [62]. Another modification has been the expression of Vip3 proteins, which are vegetative insecticidal proteins active against lepidopteran insects, along with Cry proteins [63][64][65]. Using double stranded RNA (dsRNA), a transgenic cotton has been developed against H. armigera [66]. A generalized strategy that is followed to clone Bt genes into plant genome is schematized in Figure 3.

Figure 3. Cloning Bt insecticidal genes and insertion into plant genome.

References

- Pathak, D.V.; Kumar, M.; Rani, K. Biofertilizer Application in Horticultural Crops. In Microorganisms for Green Revolution, Microorganisms for Sustainability 6; Panpatte, D., Jhala, Y., Vyas, R., Shelat, H., Eds.; Springer Nature Singapore Pte Ltd.: Singapore, 2017; pp. 215–227.

- Zambrano-Mendoza, J.L.; Sangoquiza-Caiza, C.A.; Campaña-Cruz, D.F.; Yánez-Guzmán, C.F. Use of Biofertilizers in Agricultural Production. In Technology in Agriculture; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021; Available online: https://www.intechopen.com/online-first/76918 (accessed on 23 August 2023).

- Sansinenea, E. Bacillus spp.: As plant growth-promoting bacteria. In Secondary Metabolites of Plant Growth Promoting Rhizomicroorganisms: Discovery and Applications; Singh, H.B., Keswani, C., Reddy, M.S., Sansinenea, E., García-Estrada, C., Eds.; Springer-Nature: Singapore, 2019; pp. 225–237.

- Haque, M.M.; Ilias, G.N.M.; Molla, A.H. Impact of Trichoderma-enriched biofertilizer on the growth and yield of mustard (Brassica napa L.) and tomato (Solanum lycopersicon Mill.). Agriculturists 2012, 10, 109–119.

- Chandrasekaran, M.; Chun, S.C.; Oh, J.W.; Paramasivan, M.; Saini, R.K.; Sahayarayan, J.J. Bacillus subtilis CBF05 for tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) fruits in South Korea as a novel plant probiotic bacterium (PPB): Implications from total phenolics, flavonoids, and carotenoids content for fruit quality. Agronomy 2019, 9, 838.

- Yildirim, E.; Karlidag, H.; Turan, M.; Dursun, A.; Goktepe, F. Growth, nutrient uptake, and yield promotion of Broccoli by plant growth promoting Rhizobacteria with manure. Hort. Sci. 2011, 46, 932–936.

- Malkoclu, M.C.; Tüzel, Y.; Öztekin, G.B.; Özaktan, H.; Yolageldi, L. Effects of plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria on organic lettuce production. Acta Hort. 2017, 1162, 265–272.

- Khalid, M.; Hassani, D.; Bilal, M.; Asad, F.; Huang, D. Influence of biofertilizer containing beneficial fungi and rhizospheric bacteria on health promoting compounds and antioxidant activity of Spinacia oleracea L. Bot. Stud. 2017, 58, 35.

- Dawood, M.G.; Sadak, M.S.; Abdallah, M.M.S.; Bakry, B.A.; Darwish, O.M. Influence of biofertilizers on growth and some biochemical aspects of flax cultivars grown under sandy soil conditions. Bull. Natl. Res. Cent. 2019, 43, 81.

- Yao, A.V.; Bochow, H.; Karimov, S.; Boturov, U.; Sanginboy, S.; Sharipov, A.K. Effect of FZB 241 Bacillus subtilis as a biofertilizer on cotton yields in field tests. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2006, 39, 323–328.

- Efthimiadou, A.; Katsenios, N.; Chanioti, S.; Giannoglou, M.; Djordjevic, N.; Katsaros, G. Effect of foliar and soil application of plant growth promoting bacteria on growth, physiology, yield and seed quality of maize under Mediterranean conditions. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21060.

- Martínez-Álvarez, J.C.; Castro-Martínez, C.; Sánchez-Peña, P.; Gutierrez-Dorado, R.; Maldonado-Mendoza, I.E. Development of a powder formulation based on Bacillus cereus sensu lato strain B25 spores for biological control of Fusarium verticillioides in maize plants. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2016, 32, 75.

- Khan, N.; Martínez-Hidalgo, P.; Ice, T.A.; Maymon, M.; Humm, E.A.; Nejat, N.; Sanders, E.R.; Kaplan, D.; Hirsch, A.M. Antifungal Activity of Bacillus Species Against Fusarium and Analysis of the Potential Mechanisms Used in Biocontrol. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 2363.

- Ntushelo, K.; Ledwaba, L.K.; Rauwane, M.E.; Adebo, O.A.; Njobeh, P.B. The Mode of Action of Bacillus Species against Fusarium graminearum, Tools for Investigation, and Future Prospects. Toxins 2019, 11, 606.

- Zalila-Kolsi, I.; Ben Mahmoud, A.; Ali, H.; Sellami, S.; Nasfi, Z.; Tounsi, S.; Jamoussi, K. Antagonist effects of Bacillus spp. strains against Fusarium graminearum for protection of durum wheat (Triticum turgidum L. subsp. durum). Microbiol. Res. 2016, 192, 148–158.

- Ben Khedher, M.; Nindo, F.; Chevalier, A.; Bonacorsi, S.; Dubourg, G.; Fenollar, F.; Casagrande, F.; Lotte, R.; Boyer, L.; Gallet, A.; et al. Complete Circular Genome Sequences of Three Bacillus cereus Group Strains Isolated from Positive Blood Cultures from Preterm and Immunocompromised Infants Hospitalized in France. Microbiol. Resour. Announc. 2021, 10, e0059721.

- Jiang, C.; Li, Z.; Shi, Y.; Guo, D.; Pang, B.; Chen, X.; Shao, D.; Liu, Y.; Shi, J. Bacillus subtilis inhibits Aspergillus carbonarius by producing iturin A, which disturbs the transport, energy metabolism, and osmotic pressure of fungal cells as revealed by transcriptomics analysis. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 330, 108783.

- Yuan, S.; Wu, Y.; Jin, J.; Tong, S.; Zhang, L.; Cai, Y. Biocontrol Capabilities of Bacillus subtilis E11 against Aspergillus flavus In Vitro and for Dried Red Chili (Capsicum annuum L.). Toxins 2023, 15, 308.

- Santoso, I.; Fadhilah, Q.G.; Maryanto, A.E.; Yasman. Antagonist effect of Bacillus spp. against Aspergillus niger CP isolated from cocopeat powder. In IOP Conference Series: Earth and Environmental Science, Proceedings of the 4th Life and Environmental Sciences Academics Forum, Depok, Indonesia, 6–7 November 2020; IOP Publishing: Bristol, UK, 2021; Volume 846, p. 012001.

- Veras, F.F.; Correa, A.P.; Welke, J.E.; Brandelli, A. Inhibition of mycotoxin-producing fungi by Bacillus strains isolated from fish intestines. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 238, 23–32.

- Hassan, Z.U.; Thani, R.A.; Alsafran, M.; Migheli, Q.; Jaoua, S. Selection of Bacillus spp. with decontamination potential on multiple Fusarium mycotoxins. Food Control 2021, 127, 108119.

- Bertuzzi, T.; Leni, G.; Bulla, G.; Giorni, P. Reduction of Mycotoxigenic Fungi Growth and Their Mycotoxin Production by Bacillus subtilis QST 713. Toxins 2022, 14, 797.

- Yu, J.; Hennessy, D.A.; Wu, F. The Impact of Bt Corn on Aflatoxin-Related Insurance Claims in the United States. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 10046.

- Wu, F. Mycotoxin risks are lower in biotech corn. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2022, 78, 102792.

- Ostry, V.; Ovesna, J.; Skarkova, J.; Pouchova, V.; Ruprich, J. A review on comparative data concerning Fusarium mycotoxins in Bt maize and non-Bt isogenic maize. Mycotoxin Res. 2010, 26, 141–145.

- Morais, M.C.; Mucha, A.; Ferreira, H.; Gonçalves, B.; Bacelar, E.; Marques, G. Comparative study of plant growth-promoting bacteria on the physiology, growth and fruit quality of strawberry. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2019, 99, 5341–5349.

- Mikiciuk, G.; Sas-Paszt, L.; Mikiciuk, M.; Derkowska, E.; Trzciński, P.; Gluszek, S.; Lisek, A.; Wera-Bryl, S.; Rudnicka, J. Mycorrhizal frequency, physiological parameters, and yield of strawberry plants inoculated with endomycorrhizal fungi and rhizosphere bacteria. Mycorrhiza 2019, 29, 489–501.

- Wang, B.; Shen, Z.; Zhang, F.; Waseem, R.; Yuan, J.; Huang, R.; Ruan, Y.; Li, R.; Shen, Q. Bacillus amyloliquefaciens strain W19 can promote growth and yield and suppress Fusarium wilt in banana under greenhouse and field conditions. Pedosphere 2016, 26, 733–744.

- Qiu, F.; Liu, W.; Chen, L.; Wang, Y.; Ma, Y.; Lyu, Q.; Yi, S.; Xie, R.; Zheng, Y. Bacillus subtilis biofertilizer application reduces chemical fertilization and improves fruit quality in fertigated Tarocco blood orange groves. Sci. Hortic. 2021, 281, 110004.

- Hindersah, R.; Kalay, A.M.; Kesaulya, H.; Suherman, C. The nutmeg seedlings growth under pot culture with biofertilizers inoculation. Open Agric. 2021, 6, 1–10.

- Ortiz, A.; Sansinenea, E. Chemical compounds produced by Bacillus sp. factories and their role in nature. Mini Rev. Med. Chem. 2019, 19, 373–380.

- Romero-Tabarez, M.; Jansen, R.; Sylla, M.; Lünsdorf, H.; Häussler, S.; Santosa, D.A.; Timmis, K.N.; Molinari, G. 7-O-malonyl macrolactin A, a new macrolactin antibiotic from Bacillus subtilis active against methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, vancomycin-resistant enterococci, and a small-colony variant of Burkholderia cepacia. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 1701–1709.

- Ma, Y.; Wang, W.; Zhang, H.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W.; Gao, J.; Wu, S.; Qi, G. Supplemental Bacillus subtilis DSM 32315 manipulates intestinal structure and microbial composition in broiler chickens. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 15358.

- Salazar, B.; Ortíz, A.; Keswani, C.; Minkina, T.; Mandzhieva, S.; Singh, S.P.; Rekadwad, B.; Borriss, R.; Jain, A.; Singh, H.B.; et al. Bacillus spp. as Bio factories for Antifungal Secondary Metabolites: Innovation Beyond Whole Organism Formulations. Microb. Ecol. 2023, 86, 1–24.

- Borriss, R.; Wu, H.; Gao, X. Secondary metabolites of the plant growth promoting model rhizobacterium Bacillus velezensis FZB42 are involved in direct suppression of plant pathogens and in stimulation of plant-induced systemic resistance. In Secondary Metabolites of Plant Growth Promoting Rhizomicroorganisms: Discovery and Applications; Singh, H.B., Keswani, C., Reddy, M.S., Sansinenea, E., García-Estrada, C., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 147–168.

- de Cal, A.; Larena, I.; Guijarro, B.; Melgarejo, P. Use of Biofungicides for Controlling Plant Diseases to Improve Food Availability. Agriculture 2012, 2, 109–124.

- Ortiz, A.; Sansinenea, E. Recent advancements for microorganisms and their natural compounds useful in agriculture. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 105, 891–897.

- Ortiz, A.; Sansinenea, E. Bacillus thuringiensis based biopesticides for integrated crop management. In Biopesticides, Volume 2: Advances in Bio-Inoculants; Rakshit, A., Meena, V., Abhilash, P.C., Sarma, B.K., Singh, H.B., Fraceto, L., Parihar, M., Kumar, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2022; pp. 1–6.

- Sena da Silva, I.H.; Mueller de Freitas, M.; Polanczyk, R.A. Bacillus thuringiensis, a remarkable biopesticide: From lab to the field. In Biopesticides, Volume 2: Advances in Bio-Inoculants; Rakshit, A., Meena, V., Abhilash, P.C., Sarma, B.K., Singh, H.B., Fraceto, L., Parihar, M., Kumar, A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands; Woodhead Publishing: Sawston, UK, 2022; pp. 117–131.

- Gupta, S.; Chaubey, K.K.; Khandelwal, V.; Sharma, T.; Singh, S.V. Genetic Engineering Approaches for High-End Application of Biopolymers: Advances and Future Prospects. In Microbial Polymers; Vaishnav, A., Choudhary, D.K., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2021; pp. 619–630.

- Iqbal, A.; Khan, R.S.; Khan, M.A.; Gul, K.; Jalil, F.; Shah, D.A.; Rahman, H.; Ahmed, T. Genetic Engineering Approaches for Enhanced Insect Pest Resistance in Sugarcane. Mol. Biotechnol. 2021, 63, 557–568.

- do Nascimento, J.; Goncalves, K.C.; Dias, N.P.; de Oliveira, J.L.; Bravo, A.; Polanczyk, R.A. Adoption of Bacillus thuringiensis-based biopesticides in agricultural systems and new approaches to improve their use in Brazil. Biol. Control 2022, 165, 104792.

- Bravo, A.; Gómez, I.; Porta, H.; García-Gómez, B.I.; Rodriguez-Almazan, C.; Pardo, L.; Soberón, M. Evolution of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry toxins insecticidal activity. Microb. Biotechnol. 2013, 6, 17–26.

- Peng, Q.; Yu, Q.; Song, F. Expression of cry genes in Bacillus thuringiensis biotechnology. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 1617–1626.

- Jouzani, G.S.; Valijanian, E.; Sharafi, R. Bacillus thuringiensis: A successful insecticide with new environmental features and tidings. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2017, 101, 2691–2711.

- Singh, A.; Bhardwaj, R.; Singh, I.K. Biocontrol agents: Potential of biopesticides for integrated pest management. In Biofertilizers for Sustainable Agriculture and Environment; Giri, B., Prasad, R., Wu, Q.S., Varma, A., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 413–433.

- Sansinenea, E.; Ortiz, A. Melanin: A photoprotection for Bacillus thuringiensis based biopesticides. Biotechnol. Lett. 2015, 37, 483–490.

- Hou, J.; Cong, R.; Izumi-Willcoxon, M.; Ali, H.; Zheng, Y.; Bermudez, E.; McDonald, M.; Nelson, M.; Yamamoto, T. Engineering of Bacillus thuringiensis Cry proteins to enhance the activity against western corn rootworm. Toxins 2019, 11, 162.

- Lazarte, J.N.; Valacco, M.P.; Moreno, S.; Salerno, G.L.; Berón, C.M. Molecular characterization of a Bacillus thuringiensis strain from Argentina, toxic against Lepidoptera and Coleoptera, based on its whole-genome and Cry protein analysis. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2021, 183, 107563.

- Sansinenea, E.; Vazquez, C.; Ortiz, A. Genetic manipulation in Bacillus thuringiensis for strain improvement. Biotechnol. Lett. 2010, 32, 1549–1557.

- Abbas, M.S.T. Genetically engineered (modified) crops (Bacillus thuringiensis crops) and the world controversy on their safety. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2018, 28, 52.

- Christensen, A.H.; Sharrock, R.A.; Quail, P.H. Maize polyubiquitin genes: Structure, thermal perturbation of expression and transcript splicing, and promoter activity following transfer to protoplasts by electroporation. Plant Mol. Biol. 1992, 18, 675–689.

- Liu, C.W.; Lin, C.C.; Yiu, J.C.; Chen, J.J.W.; Tseng, M.J. Expression of a Bacillus thuringiensis toxin (cry1Ab) gene in cabbage (Brassica oleracea L. var. capitata L.) chloroplasts confers high insecticidal efficacy against Plutella xylostella. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2008, 117, 75–88.

- Castagnola, A.S.; Jurat-Fuentes, J. Bt Crops: Past and Future. In Bacillus thuringiensis Biotechnology; Sansinenea, E., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2012; pp. 283–304.

- Kedisso, E.G.; Guenthner, J.; Maredia, K.; Elagib, T.; Oloo, B.; Assefa, S. Sustainable access of quality seeds of genetically engineered crops in Eastern Africa—Case study of Bt Cotton. GM Crops Food 2023, 14, 1–23.

- Gassmann, A.J.; Reisig, D.D. Management of Insect Pests with Bt Crops in the United States. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2023, 68, 31–49.

- Derua, Y.A.; Kahindi, S.C.; Mosha, F.W.; Kweka, E.J.; Atieli, H.E.; Wang, X.; Zhou, G.; Lee, M.C.; Githeko, A.K.; Yan, G. Microbial larvicides for mosquito control: Impact of long-lasting formulations of Bacillus thuringiensis var, israelensis and Bacillus sphaericus on non-target organisms in western Kenya highlands. Ecol. Evol. 2018, 8, 7563–7573.

- Anees Siddiqui, H.; Asif, M.; Zahra Naqvi, R.; Shehzad, A.; Sarwar, M.; Amin, I.; Mansoor, S. Development of modified Cry1Ac for the control of resistant insect pest of cotton, Pectinophora gossypiella. Gene 2023, 856, 147113.

- Bravo, A.; Likitvivatanavong, S.; Gill, S.S.; Soberón, M. Bacillus thuringiensis: A story of a successful bioinsecticide. Insect Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2011, 41, 423–431.

- Yunus, F.N.; Raza, G.; Makhdoom, R.; Zaheer, H. Genetic improvement of Bacillus thuringiensis against the cotton bollworm, Earias vitella (Fab.) (Lepidoptera: Noctuidae), to improve the cotton yield in Pakistan. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2019, 29, 72.

- Liu, Y.; Han, S.; Yang, S.; Chen, Z.; Yin, Y.; Xi, J.; Liu, Q.; Yan, W.; Song, X.; Zhao, F.; et al. Engineered chimeric insecticidal crystalline protein improves resistance to lepidopteran insects in rice (Oryza sativa L.) and maize (Zea mays L.). Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 12529.

- Azizoglu, U.; Salehi Jouzani, G.; Sansinenea, E.; Sanchis-Borja, V. Biotechnological advances in Bacillus thuringiensis and its toxins: Recent updates. Rev. Environ. Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 22, 319–348.

- Chen, W.B.; Lu, G.Q.; Cheng, H.M.; Liu, C.-X.; Xiao, Y.T.; Xu, C.; Shen, Z.C.; Soberón, M.; Bravo, A. Transgenic cotton co-expressing chimeric Vip3AcAa and Cry1Ac confers effective protection against Cry1Ac-resistant cotton bollworm. Transgenic Res. 2017, 26, 763–774.

- Chen, W.B.; Lu, G.Q.; Cheng, H.M.; Liu, C.-X.; Xiao, Y.T.; Xu, C.; Shen, Z.C.; Wu, K.M. Transgenic cotton co-expressing Vip3A and Cry1Ac has a broad insecticidal spectrum against lepidopteran pests. J. Invertebr. Pathol. 2017, 149, 59–65.

- Syed, T.; Askari, M.; Meng, Z.; Li, Y.; Abid, M.A.; Wei, Y.; Guo, S.; Liang, C.; Zhang, R. Current insights on vegetative insecticidal proteins (Vip) as next generation pest killers. Toxins 2020, 12, 522.

- Ni, M.; Ma, W.; Wang, X.; Gao, M.; Dai, Y.; Wei, X.; Zhang, L.; Peng, Y.; Chen, S.; Ding, L.; et al. Next-generation transgenic cotton: Pyramiding RNAi and Bt counters insect resistance. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2017, 15, 1204–1213.

More

Information

Subjects:

Microbiology

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

619

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

06 Sep 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No