Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Antonella Meloni | -- | 2668 | 2023-08-31 14:11:38 | | | |

| 2 | Sirius Huang | Meta information modification | 2668 | 2023-09-01 04:39:56 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Meloni, A.; Cademartiri, F.; Positano, V.; Celi, S.; Berti, S.; Clemente, A.; La Grutta, L.; Saba, L.; Bossone, E.; Cavaliere, C.; et al. Photon-Counting CT Technology. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/48697 (accessed on 06 February 2026).

Meloni A, Cademartiri F, Positano V, Celi S, Berti S, Clemente A, et al. Photon-Counting CT Technology. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/48697. Accessed February 06, 2026.

Meloni, Antonella, Filippo Cademartiri, Vicenzo Positano, Simona Celi, Sergio Berti, Alberto Clemente, Ludovico La Grutta, Luca Saba, Eduardo Bossone, Carlo Cavaliere, et al. "Photon-Counting CT Technology" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/48697 (accessed February 06, 2026).

Meloni, A., Cademartiri, F., Positano, V., Celi, S., Berti, S., Clemente, A., La Grutta, L., Saba, L., Bossone, E., Cavaliere, C., Punzo, B., & Maffei, E. (2023, August 31). Photon-Counting CT Technology. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/48697

Meloni, Antonella, et al. "Photon-Counting CT Technology." Encyclopedia. Web. 31 August, 2023.

Copy Citation

Photon-counting computed tomography (PCCT) is an emerging technology that can potentially transform clinical CT imaging. The improved diagnostic performance of PCCT over conventional CT in the diagnosis and characterization of cardiovascular diseases has been demonstrated in several phantom, animal, and even human studies.

photon-counting detectors

computed tomography angiography

heart

coronary arteries

1. Introduction

Cardiovascular diseases (CVDs) are the commonest cause of death worldwide and a major contributor to disability and impaired quality of life [1]. The increasing age of the global population and improvements in survival rates are expected to lead to a greater significance of CVDs in the future. Addressing the challenge of CVDs requires a comprehensive approach that includes preventive measures, early detection, effective management, and access to appropriate medical interventions. Non-invasive cardiac imaging plays a vital role in this process, enabling healthcare professionals to diagnose and evaluate the severity of cardiovascular conditions, monitor treatment outcomes, and guide therapeutic decision making. Advances in imaging technology have improved the accuracy and efficiency of these diagnostic procedures, offering valuable insights into the structure and function of the heart and blood vessels.

Cardiovascular computed tomography (CT) has experienced exponential growth in recent years and has become an integral part of clinical practice for evaluating a wide range of cardiovascular conditions [2][3]. The widespread adoption of cardiovascular CT can be attributed to its non-invasiveness and its ability to provide high-resolution images, rapid acquisition times, and three-dimensional reconstructions. However, there is still the critical need to obtain better contrast resolution and image quality at lower radiation doses, reduce blooming or beam-hardening artifacts, and improve tissue characterization capabilities [4][5][6]. Photon-counting CT (PCCT) is a promising technology that holds the potential for further improving cardiovascular CT imaging and achieving the desired goals [7]. PCCT utilizes photon-counting detectors (PCDs), which offer several benefits compared to conventional energy-integrating detectors (EIDs) used in traditional CT scanners [8][9][10][11].

2. Photon-Counting Detector Technology

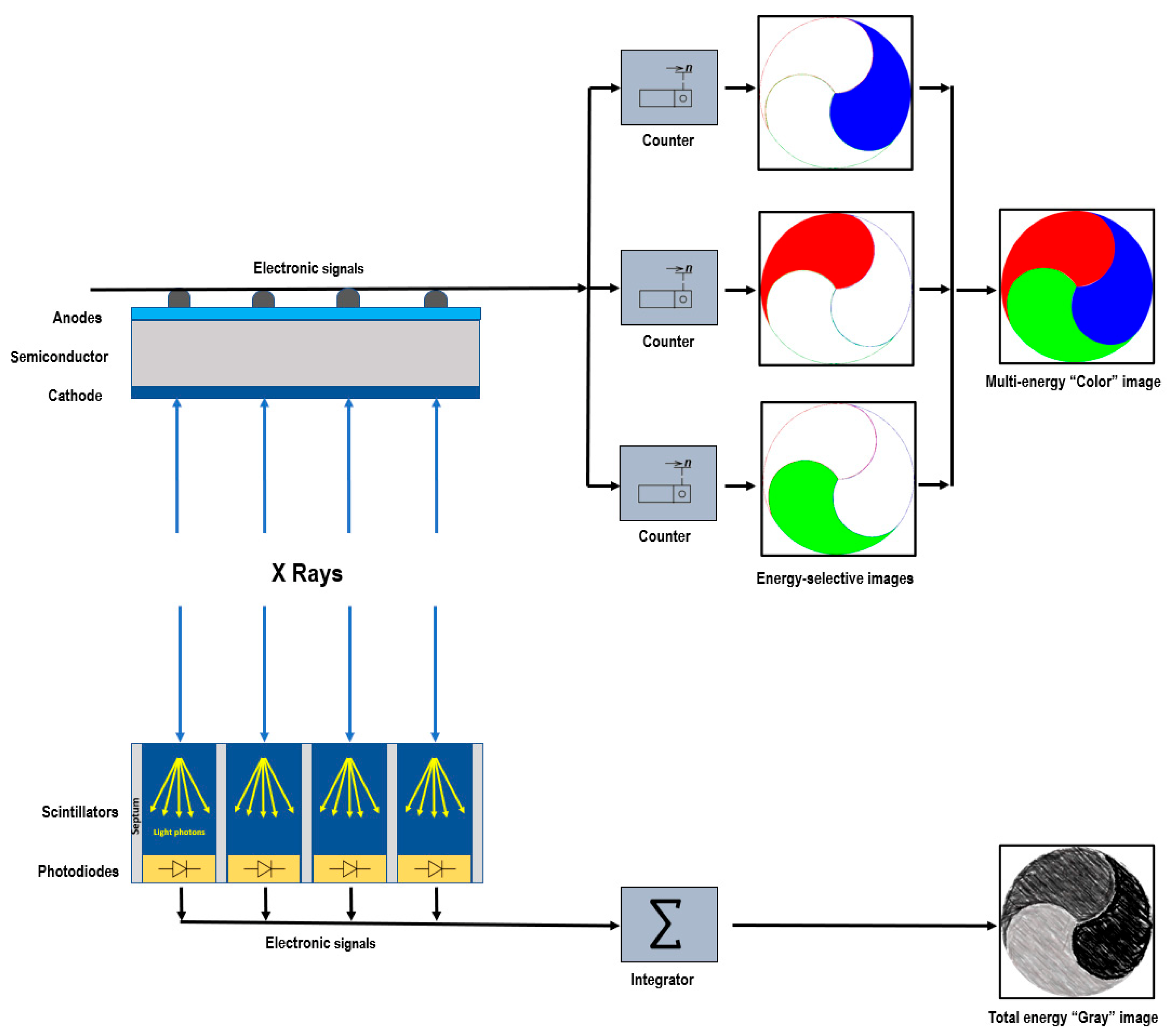

Conventional EIDs utilize a two-step indirect conversion process. Initially, the incident X-ray photons are transformed into visible light through a scintillator. Subsequently, these secondary photons are absorbed by a photodiode array and converted into electrical impulses. By integrating the energy of all X-ray photons over a specific timeframe, the detector loses the ability to retain the energy information of individual photons [12]. To avoid optical cross-talk, in EIDs, the individual detector cells are divided by optically opaque layers called septa. However, these septa create inactive areas on the detector surface and, due to their limited thickness, they impact the geometric dose efficiency [12][13].

PCDs employ a direct conversion technique [14][15]. They consist of a semiconductor layer made of cadmium telluride, cadmium zinc telluride, or silicon, with a large-area cathode electrode on the upper side and pixelated anode electrodes on the lower side (Figure 1). Applying a high voltage, typically between 800 and 1000 V, between the cathode and individual anodes creates a strong electric field. When incident X-rays are absorbed within the semiconductor, charges in the form of electron–hole pairs are generated. These charges, under the influence of the electric field, separate and move toward the anodes. As the electrons reach the anodes, they produce short current pulses, which are converted into voltage pulses by an electronic pulse-shaping circuit [16]. Since the pulse height is proportional to the photon’s energy, PCDs provide energy information for each detected photon through their output signal. The output signal from the PCD is processed by multiple electronic comparators and counters. The count of the number of generated pulses makes it possible to determine the quantity of the interacting X-ray photons.

Figure 1. Schematic representation of photon-counting detector directly converting X-rays into an electrical signal (top) and of an energy-integrating detector (bottom).

Furthermore, pulse heights can be compared with a voltage corresponding to a particular photon energy level, denoted as energy threshold [17]. When the energy level of a detected photon is higher than the threshold value, the photon count is incremented by one. This counting process allows us to measure the number of photons with energy equal to or greater than the specified energy level [18] and to sort them into several energy bins (typically two to eight). The lower threshold is typically set higher than the electronic noise level to ensure that the noise is effectively eliminated or suppressed in the final signal. The other thresholds can be uniformly spaced or chosen strategically to optimize the desired imaging outcome [19].

3. Benefits of PCDs

This section describes the benefits the PCCT system offers compared to conventional CT technology.

3.1. Higher Spatial Resolution

The spatial resolution of a CT measurement is influenced by several factors, including some physical properties of the scanner, like the X-ray source (focal spot size) and the detector (pixel size and scattering).

Recent advancements in EIDs have led to improvements in spatial resolution, with pixel pitches being approximately 0.5 mm at the detector [20]. However, the need for highly reflecting layers poses challenges in manufacturing smaller detector element areas. The septa cannot be made too thin, as it would result in photon cross-talk and degrade image quality. Additionally, the design of smaller detector pixels would cause an overall decrease in the detector area sensitive to X-rays, with a consequent decrease in the geometric dose efficiency [16].

Since in PCDs there are no reflectors or dead areas between pixels, the pixels can be made smaller without sacrificing the geometric efficiency [16]. The pixel pitch can reach 0.15–0.225 mm at the isocenter [21][22][23][24], translating into a higher spatial resolution. The improved spatial resolution is the key to the generation of clearer and more detailed images and to the reduction in partial volume effects.

3.2. Increased Contrast

In conventional EIDs, photons are typically weighted based on their energy, and high-energy photons tend to contribute to the signal more than low-energy photons. Since low-energy photons carry valuable information about the contrast between different materials, their underweighting can reduce the contrast-to-noise ratio (CNR) [16][25]. Additionally, the non-uniform weighting of photons leads to an increase in the variance relative to the mean value, reducing the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR). This phenomenon is known as the Swank factor [26].

In PCDs, all photons are equally weighted regardless of their energy (one photon, one count). Assigning relatively more weight to low-energy photons can result in higher contrast than EIDs, especially for materials with low X-ray attenuation [27][28][29][30]. Importantly, the weighting scheme in PCDs can be customized to optimize the CNR for specific materials or imaging tasks [16][31]. Moreover, PCDs, by counting each photon individually, eliminate the Swank factor and its associated impact on image quality.

3.3. Noise Reduction

The energy-discriminating ability of PCDs is instrumental in minimizing the impact of the electronic noise, which can decrease image uniformity and cause noticeable streak artifacts. When the low-energy threshold of a PCD is set above the noise-floor level (typically around 20–25 keV), any electronic noise signals below this threshold are not considered valid photon events or pulse counts [18]. However, although the electronic noise can be effectively removed from photon and/or pulse counts, it still persists in the spectral information.

The capacity of PCDs to eliminate electronic noise is particularly advantageous in scenarios involving low-dose CT scans or patients with high body mass, where noise can be a significant concern. In such scenarios, PCDs have been found to provide reduced streak artifacts, improved signal uniformity, and more stable CT numbers than conventional EIDs [32][33]. Importantly, the reduced noise levels in PCDs allow for dose-efficient imaging, achieving comparable image quality to EIDs while using lower radiation doses. These benefits contribute to improved diagnostic accuracy and patient safety in CT imaging.

3.4. Multienergy Acquisition

Spectral CT harnesses the intrinsic energy-dependent information embedded within CT images, enabling a deeper understanding of the underlying tissue composition and opening up new avenues for diagnostic imaging.

One of the primary mechanisms employed in spectral CT is material decomposition. The application of sophisticated algorithms on a series of energy-selective images allows to generate a collection of basis image maps. The number of bases aligns with the quantity of gathered spectral information (N bases for N spectral data), and it can be enlarged to N + 1 by imposing mass or volume conservation constraints, albeit with a risk of introducing inaccuracies [34]. Each basis image map depicts the concentration of the equivalent substance voxel by voxel. These basic material images provide a multitude of visualization alternatives. They can be immediately showcased to illustrate the distribution of specific materials, such as contrast agents, within the imaged area. Alternatively, these images can go through additional manipulation to generate virtual monochromatic images (VMI) [35][36][37], virtual non-contrast (VNC) images [38], or material-specific color-overlay images [39]. Conventional CT acquires data in two energy regimes and can accurately isolate a single contrast agent, like iodine, from the background without any underlying assumptions. However, it faces limitations when differentiating two contrast materials with high atomic numbers (high Z). PCDs play a crucial role in overcoming this challenge. Their ability to discriminate photons of different energies through pulse-height analysis enables the acquisition of simultaneous multi-energy data (N ≥ 2) with impeccable spatial and temporal registrations and lacking spectral overlap [40]. The expansion of the number of energy regimens in spectral CT significantly enhances the precision of measuring each photon energy, leading to improved material-specific or weighted images [41][42]. Concentrations of contrast agents, calcium, or other substances can be quantified independently of acquisition parameters, leading to improved quantitative analysis.

Another advantage of employing multiple energy measurements in spectral CT is the ability to quantify elements with K-edges within the diagnostic energy range. Indeed, by acquiring CT data at multiple energy levels, spectral PCCT can effectively measure the X-ray attenuation profiles of different materials, taking advantage of their distinct K-edge energies. This information enables the identification and quantification of various elements with distinct pharmacokinetics within the same biological system. Multi-energy acquisition opens avenues for the use of alternative contrast agents to iodine, such as gold, platinum, silver, ytterbium, and bismuth [43][44][45][46], and for the development of new types of contrast agents, including nanoparticles targeted to specific cells or enzymes [47][48][49][50]. These unique opportunities pave the way for molecular and functional CT imaging as well as simultaneous multi-contrast agent imaging [39][51][52][53], empowering clinicians with advanced tools for precise diagnosis and treatment planning.

3.5. Artifact Reduction

Artifacts are commonly observed in clinical CT and can mimic or obscure true pathology.

Beam-hardening artifacts occur when the X-ray beam passing through an object is more attenuated by high-density materials than by low-density materials (soft tissues). This uneven attenuation causes a distortion of the reconstructed CT images, resulting in streaking or shading artifacts [54]. In PCDs, constant weighting allows normalizing the attenuation measurements from different energy levels, reducing the beam-hardening artifacts [55][56]. In this context, using high-energy thresholds that act as a filter is particularly advantageous [32][57].

Calcium-blooming and metal artifacts are caused by volume averaging, motion, and beam hardening [58]. These artifacts are significantly mitigated in PCDs thanks to the improved spatial resolution and the consequent decrease in partial volume effects and thanks to the improved material decomposition allowing for accurate separation of the high-density materials (such as metals) from the surrounding soft tissues [59].

PCCT’s faster acquisition times enable shorter scan durations, reducing the chance of motion artifacts caused by patient movement.

4. Challenges of PCCT Technology

Alongside the advantages, there are also limitations associated with using PCCT technology. These limitations must be considered when assessing its potential impact on clinical CT imaging.

4.1. Technical Challenges

PCCT faces technical challenges such as charge sharing, pixel cross-talk, and pulse pile-up [13][60].

Charge sharing is a phenomenon that occurs in PCDs when X-ray photons arrive near the boundary between pixels. In such cases, the charge generated by the X-ray interaction can spread or “share” across multiple adjacent pixel electrodes. As a result, the charge may be detected in more than one pixel, leading to the incorrect assignment of charge to multiple pixels instead of just one [61][62][63]. When charge sharing occurs, it can distort the distribution of detected photons and introduce artifacts in the image. Researchers and manufacturers continue exploring and refining techniques (development of advanced correction methods and optimization of detector design) to minimize the effects of charge sharing in PCDs. Besides charge sharing, there are other types of pixel cross-talk that can affect the performance of the detector, like the K-fluorescence escape. This phenomenon occurs when secondary photons from fluorescence in the detector material escape the original pixel and are detected in neighboring pixels [18]. These effects place a lower limit on the practical pixel size in PCD applications.

Pulse pile-up occurs when the generated voltage pulses from individual photon interactions overlap in time, especially at very high X-ray flux rates. This overlapping of pulses can cause errors in photon counting and energy measurement, resulting in distorted energy spectra and compromising image quality [64][65]. One way to mitigate pulse pile-up is to decrease the pixel size of the detector. However, it is important to note that at realistic X-ray flux rates encountered in clinical CT imaging, the effect of pulse pile-up is generally not a major concern [64].

4.2. Contrast Agents and K-Edge Imaging

Compared to other imaging modalities, PCCT may require higher doses of gadolinium. The higher dosage can raise concerns about patient safety and potential adverse effects. It is crucial to carefully monitor and optimize the dosage to balance diagnostic accuracy and potential risks.

The clinical translation of nanoparticles is still in the experimental stage, and further research is needed to evaluate their safety, efficacy, and potential advantages over conventional contrast agents.

4.3. Clinical Validation

While PCCT shows promising potential in cardiovascular imaging and other applications, further clinical validation and comparative studies are needed to establish its diagnostic accuracy, clinical utility, and impact on patient outcomes.

4.4. Cost and Availability

The development and production of PCD are expensive, and the high cost poses a significant barrier to the widespread adoption of PCCT in clinical settings [66]. However, when the technology becomes more established, a significant cost reduction is expected to occur.

Currently, the only clinical scanner with PCCT capabilities is the NAEOTOM ALPHA from Siemens (Germany). It was developed on the platform of the most developed EID scanner (non-PCD detector; state-of-the-art Dual-Source CT scanner, FORCE from Siemens), and it has basically the same starting technical features. Therefore, the NAEOTOM ALPHA is a development of the highest performing non-PCCT scanner.

4.5. Acquisition of Images in Cardio-Synchronized Exam

There are limits that are related to the scanner features. Anatomical coverage is not limited because it can be achieved with ultra-fast high-pitch (FLASH) protocol (pitch 3.2). The temporal resolution is the same as the best non-PCCT scanner (i.e., 66 ms). Arrhythmias and high heart rate require the same approach as the above-mentioned state-of-the-art Dual-Source non-PCCT scanner (e.g., systolic scan and retrospective ECG gating) [67].

5. Cardiovascular Applications of PPCT

The improved diagnostic performance of PCCT over conventional CT in the diagnosis and characterization of cardiovascular diseases has been demonstrated in several phantom, animal, and even human studies. This section provides a summary of these studies.

Table 1 sums up the applications and the main advantages of PCCT in cardiovascular imaging.

Table 1. Cardiovascular applications of PPCT.

| Cardiovascular Applications of PCCT |

|---|

| Improved visualization of coronary plaques and patent lumen over conventional CT |

| Superior accuracy in the quantification of luminal stenosis across all plaque types compared to conventional CT |

| Improved accuracy in coronary artery calcium quantification compared to conventional CT |

| Improved detection of coronary calcium even at a reduced radiation dose compared to conventional CT |

| Anatomic assessment of plaque composition: differentiation among calcified, fibrous, and lipid-rich plaques and identification of features such as thinning of the fibrous cap or presence of intraplaque hemorrhage |

| Potential capability to provide information about the biological activity within the coronary plaque, such as inflammation or neovascularization |

| Better visualization of the stent lumen compared to conventional CT |

| Improved detection of in-stent restenosis compared to conventional CT |

| Quantification of myocardial extracellular volume at a low radiation dose |

| Accurate delineation of myocardial scar achieved thanks to the excellent contrast between infarcted myocardium, remote myocardium, and left ventricular blood pool |

| Detection of myocardial perfusion defects |

| Improved extraction myocardial radiomics features compared to conventional CT |

| Accurate quantification of epicardial adipose tissue volume and assessment of pericoronary adipose tissue attenuation |

| Reduction in the volume of iodine-based contrast media in coronary CT angiography without compromising the diagnostic image quality |

References

- Roth, G.A.; Mensah, G.A.; Johnson, C.O.; Addolorato, G.; Ammirati, E.; Baddour, L.M.; Barengo, N.C.; Beaton, A.Z.; Benjamin, E.J.; Benziger, C.P.; et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990–2019: Update from the GBD 2019 Study. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2020, 76, 2982–3021.

- Daubert, M.A.; Tailor, T.; James, O.; Shaw, L.J.; Douglas, P.S.; Koweek, L. Multimodality cardiac imaging in the 21st century: Evolution, advances and future opportunities for innovation. Br. J. Radiol. 2021, 94, 20200780.

- Pontone, G.; Rossi, A.; Guglielmo, M.; Dweck, M.R.; Gaemperli, O.; Nieman, K.; Pugliese, F.; Maurovich-Horvat, P.; Gimelli, A.; Cosyns, B.; et al. Clinical applications of cardiac computed tomography: A consensus paper of the European Association of Cardiovascular Imaging-part I. Eur. Heart J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 23, 299–314.

- FitzGerald, P.; Bennett, J.; Carr, J.; Edic, P.M.; Entrikin, D.; Gao, H.; Iatrou, M.; Jin, Y.; Liu, B.; Wang, G.; et al. Cardiac CT: A system architecture study. J. Xray Sci. Technol. 2016, 24, 43–65.

- Meloni, A.; Frijia, F.; Panetta, D.; Degiorgi, G.; De Gori, C.; Maffei, E.; Clemente, A.; Positano, V.; Cademartiri, F. Photon-Counting Computed Tomography (PCCT): Technical Background and Cardio-Vascular Applications. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 645.

- Cademartiri, F.; Meloni, A.; Pistoia, L.; Degiorgi, G.; Clemente, A.; Gori, C.; Positano, V.; Celi, S.; Berti, S.; Emdin, M.; et al. Dual-Source Photon-Counting Computed Tomography-Part I: Clinical Overview of Cardiac CT and Coronary CT Angiography Applications. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3627.

- Meloni, A.; Cademartiri, F.; Pistoia, L.; Degiorgi, G.; Clemente, A.; De Gori, C.; Positano, V.; Celi, S.; Berti, S.; Emdin, M.; et al. Dual-Source Photon-Counting Computed Tomography-Part III: Clinical Overview of Vascular Applications beyond Cardiac and Neuro Imaging. J. Clin. Med. 2023, 12, 3798.

- Boussel, L.; Coulon, P.; Thran, A.; Roessl, E.; Martens, G.; Sigovan, M.; Douek, P. Photon counting spectral CT component analysis of coronary artery atherosclerotic plaque samples. Br. J. Radiol. 2014, 87, 20130798.

- Skoog, S.; Henriksson, L.; Gustafsson, H.; Sandstedt, M.; Elvelind, S.; Persson, A. Comparison of the Agatston score acquired with photon-counting detector CT and energy-integrating detector CT: Ex vivo study of cadaveric hearts. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2022, 38, 1145–1155.

- Polacin, M.; Templin, C.; Manka, R.; Alkadhi, H. Photon-counting computed tomography for the diagnosis of myocardial infarction with non-obstructive coronary artery disease. Eur. Heart J. Case Rep. 2022, 6, ytac028.

- Koons, E.; VanMeter, P.; Rajendran, K.; Yu, L.; McCollough, C.; Leng, S. Improved quantification of coronary artery luminal stenosis in the presence of heavy calcifications using photon-counting detector CT. Proc. SPIE Int. Soc. Opt. Eng. 2022, 12031, 120311A.

- Willemink, M.J.; Persson, M.; Pourmorteza, A.; Pelc, N.J.; Fleischmann, D. Photon-counting CT: Technical Principles and Clinical Prospects. Radiology 2018, 289, 293–312.

- Kreisler, B. Photon counting Detectors: Concept, technical Challenges, and clinical outlook. Eur. J. Radiol. 2022, 149, 110229.

- Leng, S.; Bruesewitz, M.; Tao, S.; Rajendran, K.; Halaweish, A.F.; Campeau, N.G.; Fletcher, J.G.; McCollough, C.H. Photon-counting Detector CT: System Design and Clinical Applications of an Emerging Technology. Radiographics 2019, 39, 729–743.

- Esquivel, A.; Ferrero, A.; Mileto, A.; Baffour, F.; Horst, K.; Rajiah, P.S.; Inoue, A.; Leng, S.; McCollough, C.; Fletcher, J.G. Photon-Counting Detector CT: Key Points Radiologists Should Know. Korean J. Radiol. 2022, 23, 854–865.

- Danielsson, M.; Persson, M.; Sjölin, M. Photon-counting X-ray detectors for CT. Phys. Med. Biol. 2021, 66, 03TR01.

- Tortora, M.; Gemini, L.; D’Iglio, I.; Ugga, L.; Spadarella, G.; Cuocolo, R. Spectral Photon-Counting Computed Tomography: A Review on Technical Principles and Clinical Applications. J. Imaging 2022, 8, 112.

- Taguchi, K.; Iwanczyk, J.S. Vision 20/20: Single photon counting X-ray detectors in medical imaging. Med. Phys. 2013, 40, 100901.

- Zheng, Y.; Yveborg, M.; Grönberg, F.; Xu, C.; Su, Q.; Danielsson, M.; Persson, M. Robustness of optimal energy thresholds in photon-counting spectral CT. Nucl. Instrum. Methods Phys. Res. Sect. A Accel. Spectrometers Detect. Assoc. Equip. 2020, 953, 163132.

- Yanagawa, M.; Hata, A.; Honda, O.; Kikuchi, N.; Miyata, T.; Uranishi, A.; Tsukagoshi, S.; Tomiyama, N. Subjective and objective comparisons of image quality between ultra-high-resolution CT and conventional area detector CT in phantoms and cadaveric human lungs. Eur. Radiol. 2018, 28, 5060–5068.

- Si-Mohamed, S.A.; Sigovan, M.; Hsu, J.C.; Tatard-Leitman, V.; Chalabreysse, L.; Naha, P.C.; Garrivier, T.; Dessouky, R.; Carnaru, M.; Boussel, L.; et al. In Vivo Molecular K-Edge Imaging of Atherosclerotic Plaque Using Photon-counting CT. Radiology 2021, 300, 98–107.

- Leng, S.; Rajendran, K.; Gong, H.; Zhou, W.; Halaweish, A.F.; Henning, A.; Kappler, S.; Baer, M.; Fletcher, J.G.; McCollough, C.H. 150-μm Spatial Resolution Using Photon-Counting Detector Computed Tomography Technology: Technical Performance and First Patient Images. Investig. Radiol. 2018, 53, 655–662.

- Ferda, J.; Vendiš, T.; Flohr, T.; Schmidt, B.; Henning, A.; Ulzheimer, S.; Pecen, L.; Ferdová, E.; Baxa, J.; Mírka, H. Computed tomography with a full FOV photon-counting detector in a clinical setting, the first experience. Eur. J. Radiol. 2021, 137, 109614.

- Rajendran, K.; Petersilka, M.; Henning, A.; Shanblatt, E.R.; Schmidt, B.; Flohr, T.G.; Ferrero, A.; Baffour, F.; Diehn, F.E.; Yu, L.; et al. First Clinical Photon-counting Detector CT System: Technical Evaluation. Radiology 2022, 303, 130–138.

- Sandfort, V.; Persson, M.; Pourmorteza, A.; Noël, P.B.; Fleischmann, D.; Willemink, M.J. Spectral photon-counting CT in cardiovascular imaging. J. Cardiovasc. Comput. Tomogr. 2021, 15, 218–225.

- Swank, R.K. Absorption and noise in X-ray phosphors. J. Appl. Phys. 1973, 44, 4199–4203.

- Iwanczyk, J.S.; Nygård, E.; Meirav, O.; Arenson, J.; Barber, W.C.; Hartsough, N.E.; Malakhov, N.; Wessel, J.C. Photon Counting Energy Dispersive Detector Arrays for X-ray Imaging. IEEE Trans. Nucl. Sci. 2009, 56, 535–542.

- Shikhaliev, P.M. Energy-resolved computed tomography: First experimental results. Phys. Med. Biol. 2008, 53, 5595–5613.

- Shikhaliev, P.M.; Fritz, S.G. Photon counting spectral CT versus conventional CT: Comparative evaluation for breast imaging application. Phys. Med. Biol. 2011, 56, 1905–1930.

- Silkwood, J.D.; Matthews, K.L.; Shikhaliev, P.M. Photon counting spectral breast CT: Effect of adaptive filtration on CT numbers, noise, and contrast to noise ratio. Med. Phys. 2013, 40, 051905.

- Schmidt, T.G. Optimal “image-based” weighting for energy-resolved CT. Med. Phys. 2009, 36, 3018–3027.

- Yu, Z.; Leng, S.; Kappler, S.; Hahn, K.; Li, Z.; Halaweish, A.F.; Henning, A.; McCollough, C.H. Noise performance of low-dose CT: Comparison between an energy integrating detector and a photon counting detector using a whole-body research photon counting CT scanner. J. Med. Imaging 2016, 3, 043503.

- Symons, R.; Cork, T.E.; Sahbaee, P.; Fuld, M.K.; Kappler, S.; Folio, L.R.; Bluemke, D.A.; Pourmorteza, A. Low-dose lung cancer screening with photon-counting CT: A feasibility study. Phys. Med. Biol. 2017, 62, 202–213.

- Yveborg, M.; Danielsson, M.; Bornefalk, H. Theoretical comparison of a dual energy system and photon counting silicon detector used for material quantification in spectral CT. IEEE Trans. Med. Imaging 2015, 34, 796–806.

- Symons, R.; Reich, D.S.; Bagheri, M.; Cork, T.E.; Krauss, B.; Ulzheimer, S.; Kappler, S.; Bluemke, D.A.; Pourmorteza, A. Photon-Counting Computed Tomography for Vascular Imaging of the Head and Neck: First In Vivo Human Results. Investig. Radiol. 2018, 53, 135–142.

- Leng, S.; Zhou, W.; Yu, Z.; Halaweish, A.; Krauss, B.; Schmidt, B.; Yu, L.; Kappler, S.; McCollough, C. Spectral performance of a whole-body research photon counting detector CT: Quantitative accuracy in derived image sets. Phys. Med. Biol. 2017, 62, 7216–7232.

- Laukamp, K.R.; Lennartz, S.; Neuhaus, V.F.; Große Hokamp, N.; Rau, R.; Le Blanc, M.; Abdullayev, N.; Mpotsaris, A.; Maintz, D.; Borggrefe, J. CT metal artifacts in patients with total hip replacements: For artifact reduction monoenergetic reconstructions and post-processing algorithms are both efficient but not similar. Eur. Radiol. 2018, 28, 4524–4533.

- Mergen, V.; Racine, D.; Jungblut, L.; Sartoretti, T.; Bickel, S.; Monnin, P.; Higashigaito, K.; Martini, K.; Alkadhi, H.; Euler, A. Virtual Noncontrast Abdominal Imaging with Photon-counting Detector CT. Radiology 2022, 305, 107–115.

- Symons, R.; Krauss, B.; Sahbaee, P.; Cork, T.E.; Lakshmanan, M.N.; Bluemke, D.A.; Pourmorteza, A. Photon-counting CT for simultaneous imaging of multiple contrast agents in the abdomen: An in vivo study. Med. Phys. 2017, 44, 5120–5127.

- Kappler, S.; Henning, A.; Kreisler, B.; Schoeck, F.; Stierstorfer, K.; Flohr, T. Photon Counting CT at Elevated X-Ray Tube Currents: Contrast Stability, Image Noise and Multi-Energy Performance; SPIE: Paris, France, 2014; Volume 9033.

- Faby, S.; Kuchenbecker, S.; Sawall, S.; Simons, D.; Schlemmer, H.P.; Lell, M.; Kachelrieß, M. Performance of today’s dual energy CT and future multi energy CT in virtual non-contrast imaging and in iodine quantification: A simulation study. Med. Phys. 2015, 42, 4349–4366.

- Shikhaliev, P.M. Computed tomography with energy-resolved detection: A feasibility study. Phys. Med. Biol. 2008, 53, 1475–1495.

- Schirra, C.O.; Brendel, B.; Anastasio, M.A.; Roessl, E. Spectral CT: A technology primer for contrast agent development. Contrast Media Mol. Imaging 2014, 9, 62–70.

- Pan, D.; Schirra, C.O.; Senpan, A.; Schmieder, A.H.; Stacy, A.J.; Roessl, E.; Thran, A.; Wickline, S.A.; Proska, R.; Lanza, G.M. An early investigation of ytterbium nanocolloids for selective and quantitative “multicolor” spectral CT imaging. ACS Nano 2012, 6, 3364–3370.

- Müllner, M.; Schlattl, H.; Hoeschen, C.; Dietrich, O. Feasibility of spectral CT imaging for the detection of liver lesions with gold-based contrast agents–A simulation study. Phys. Med. 2015, 31, 875–881.

- Kim, J.; Bar-Ness, D.; Si-Mohamed, S.; Coulon, P.; Blevis, I.; Douek, P.; Cormode, D.P. Assessment of candidate elements for development of spectral photon-counting CT specific contrast agents. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 12119.

- Si-Mohamed, S.; Cormode, D.P.; Bar-Ness, D.; Sigovan, M.; Naha, P.C.; Langlois, J.-B.; Chalabreysse, L.; Coulon, P.; Blevis, I.; Roessl, E.; et al. Evaluation of spectral photon counting computed tomography K-edge imaging for determination of gold nanoparticle biodistribution in vivo. Nanoscale 2017, 9, 18246–18257.

- Cormode, D.P.; Roessl, E.; Thran, A.; Skajaa, T.; Gordon, R.E.; Schlomka, J.P.; Fuster, V.; Fisher, E.A.; Mulder, W.J.; Proksa, R.; et al. Atherosclerotic plaque composition: Analysis with multicolor CT and targeted gold nanoparticles. Radiology 2010, 256, 774–782.

- Balegamire, J.; Vandamme, M.; Chereul, E.; Si-Mohamed, S.; Azzouz Maache, S.; Almouazen, E.; Ettouati, L.; Fessi, H.; Boussel, L.; Douek, P.; et al. Iodinated polymer nanoparticles as contrast agent for spectral photon counting computed tomography. Biomater. Sci. 2020, 8, 5715–5728.

- Dong, Y.C.; Kumar, A.; Rosario-Berríos, D.N.; Si-Mohamed, S.; Hsu, J.C.; Nieves, L.M.; Douek, P.; Noël, P.B.; Cormode, D.P. Ytterbium Nanoparticle Contrast Agents for Conventional and Spectral Photon-Counting CT and Their Applications for Hydrogel Imaging. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2022, 14, 39274–39284.

- Muenzel, D.; Daerr, H.; Proksa, R.; Fingerle, A.A.; Kopp, F.K.; Douek, P.; Herzen, J.; Pfeiffer, F.; Rummeny, E.J.; Noël, P.B. Simultaneous dual-contrast multi-phase liver imaging using spectral photon-counting computed tomography: A proof-of-concept study. Eur. Radiol. Exp. 2017, 1, 25.

- Symons, R.; Cork, T.E.; Lakshmanan, M.N.; Evers, R.; Davies-Venn, C.; Rice, K.A.; Thomas, M.L.; Liu, C.Y.; Kappler, S.; Ulzheimer, S.; et al. Dual-contrast agent photon-counting computed tomography of the heart: Initial experience. Int. J. Cardiovasc. Imaging 2017, 33, 1253–1261.

- Cormode, D.P.; Si-Mohamed, S.; Bar-Ness, D.; Sigovan, M.; Naha, P.C.; Balegamire, J.; Lavenne, F.; Coulon, P.; Roessl, E.; Bartels, M.; et al. Multicolor spectral photon-counting computed tomography: In vivo dual contrast imaging with a high count rate scanner. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 4784.

- Barrett, J.F.; Keat, N. Artifacts in CT: Recognition and avoidance. Radiographics 2004, 24, 1679–1691.

- Shikhaliev, P.M. Beam hardening artefacts in computed tomography with photon counting, charge integrating and energy weighting detectors: A simulation study. Phys. Med. Biol. 2005, 50, 5813–5827.

- Lee, C.-L.; Park, J.; Nam, S.; Choi, J.; Choi, Y.; Lee, S.; Lee, K.-Y.; Cho, M. Metal artifact reduction and tumor detection using photon-counting multi-energy computed tomography. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0247355.

- Gutjahr, R.; Halaweish, A.F.; Yu, Z.; Leng, S.; Yu, L.; Li, Z.; Jorgensen, S.M.; Ritman, E.L.; Kappler, S.; McCollough, C.H. Human Imaging With Photon Counting-Based Computed Tomography at Clinical Dose Levels: Contrast-to-Noise Ratio and Cadaver Studies. Investig. Radiol. 2016, 51, 421–429.

- Pack, J.D.; Xu, M.; Wang, G.; Baskaran, L.; Min, J.; De Man, B. Cardiac CT blooming artifacts: Clinical significance, root causes and potential solutions. Vis. Comput. Ind. Biomed. Art. 2022, 5, 29.

- Si-Mohamed, S.A.; Boccalini, S.; Lacombe, H.; Diaw, A.; Varasteh, M.; Rodesch, P.-A.; Dessouky, R.; Villien, M.; Tatard-Leitman, V.; Bochaton, T.; et al. Coronary CT Angiography with Photon-counting CT: First-In-Human Results. Radiology 2022, 303, 303–313.

- Rajiah, P.; Parakh, A.; Kay, F.; Baruah, D.; Kambadakone, A.R.; Leng, S. Update on Multienergy CT: Physics, Principles, and Applications. Radiographics 2020, 40, 1284–1308.

- Cammin, J.; Xu, J.; Barber, W.C.; Iwanczyk, J.S.; Hartsough, N.E.; Taguchi, K. A cascaded model of spectral distortions due to spectral response effects and pulse pileup effects in a photon-counting X-ray detector for CT. Med. Phys. 2014, 41, 041905.

- Wang, A.S.; Harrison, D.; Lobastov, V.; Tkaczyk, J.E. Pulse pileup statistics for energy discriminating photon counting X-ray detectors. Med. Phys. 2011, 38, 4265–4275.

- Nakamura, Y.; Higaki, T.; Kondo, S.; Kawashita, I.; Takahashi, I.; Awai, K. An introduction to photon-counting detector CT (PCD CT) for radiologists. Jpn. J. Radiol. 2022, 41, 266–282.

- Flohr, T.; Schmidt, B. Technical Basics and Clinical Benefits of Photon-Counting CT. Investig. Radiol. 2023, 58, 441–450.

- Wang, A.S.; Pelc, N.J. Spectral Photon Counting CT: Imaging Algorithms and Performance Assessment. IEEE Trans. Radiat. Plasma Med. Sci. 2021, 5, 453–464.

- Pourmorteza, A. Photon-counting CT: Scouting for Quantitative Imaging Biomarkers. Radiology 2021, 298, 153–154.

- Miller, R.J.H.; Eisenberg, E.; Friedman, J.; Cheng, V.; Hayes, S.; Tamarappoo, B.; Thomson, L.; Berman, D.S. Impact of heart rate on coronary computed tomographic angiography interpretability with a third-generation dual-source scanner. Int. J. Cardiol. 2019, 295, 42–47.

More

Information

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

1.5K

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

01 Sep 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No