Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | domenico prisa | -- | 2754 | 2023-08-07 10:50:20 | | | |

| 2 | Jessie Wu | Meta information modification | 2754 | 2023-08-08 04:52:28 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Prisa, D.; Spagnuolo, D. Potential of Microalgal Biostimulants for Sustainable Agricultural Practices. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/47721 (accessed on 03 March 2026).

Prisa D, Spagnuolo D. Potential of Microalgal Biostimulants for Sustainable Agricultural Practices. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/47721. Accessed March 03, 2026.

Prisa, Domenico, Damiano Spagnuolo. "Potential of Microalgal Biostimulants for Sustainable Agricultural Practices" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/47721 (accessed March 03, 2026).

Prisa, D., & Spagnuolo, D. (2023, August 07). Potential of Microalgal Biostimulants for Sustainable Agricultural Practices. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/47721

Prisa, Domenico and Damiano Spagnuolo. "Potential of Microalgal Biostimulants for Sustainable Agricultural Practices." Encyclopedia. Web. 07 August, 2023.

Copy Citation

Plant biostimulants have long been considered an important source of plant growth stimulants in agronomy and agro-industries with both macroalgae (seaweeds) and microalgae (microalgae). There has been extensive exploration of macroalgae biostimulants.

algae biostimulants

sustainable agriculture

microalgae

crop nutrition

biofertiliser

crop protection products

1. Microalgae as a New Source of Biostimulants

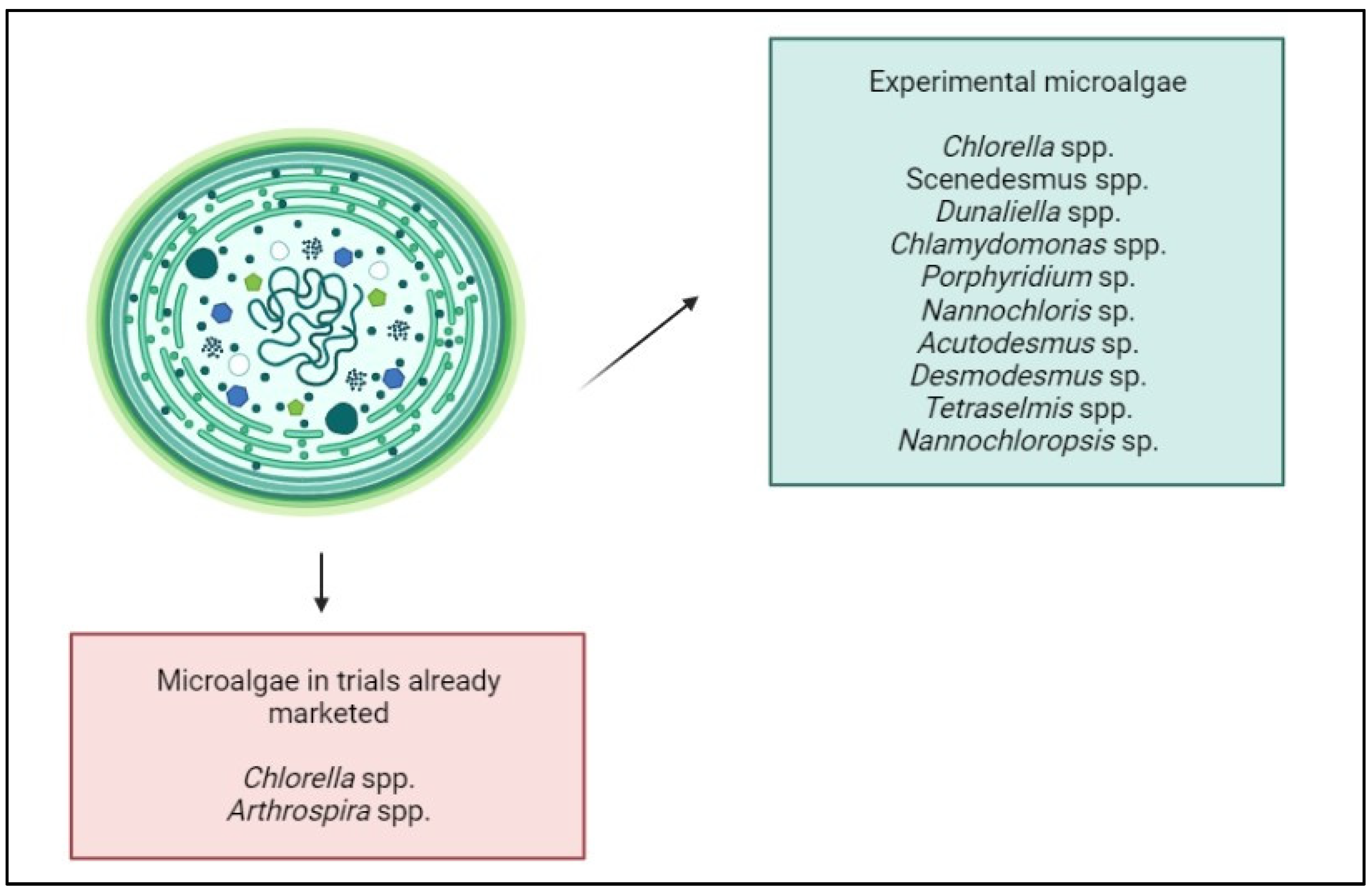

The agricultural applications of microalgae have long focused on their use as biofertilisers and soil conditioners whose effects on crops are mainly attributable to the improvement of physical, chemical, and biological soil fertility [1]. However, in recent years, numerous studies have shown that the variety of physiological responses in plants following the application of these microbial biomasses cannot solely be attributed to the increases in the nutrients available to plants but also derives from the action of a wide range of bioactive molecules (e.g., phytohormones, amino acids, vitamins, polysaccharides, carbohydrates, polyamines, polyphenols) that are effective on plants at concentrations considerably lower than those of the macroelements (such as nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium) contained in biofertilisers [2][3]. The ability of microalgae to produce these bioactive molecules, which plants can absorb and metabolise both foliarly and through the root, and the possibility of improving crop productivity using very small quantities of the product compared to biofertilisers has led the scientific community and companies to take an interest in studying the biostimulant properties of these microalgae [4]. Considering that most of the results in this field have been published in recent years and that very few microalgae- and cyanobacteria-based biostimulant products are available on the market today, we can say that the research in this area, although very promising, is still in its infancy [2][5]. Due to the enormous biodiversity of these microorganisms (it is estimated that only half of the approximately 55,000 existing species of microalgae and cyanobacteria have been described to date) [6], only a small number of strains belonging to a few genera have been investigated for their biostimulant properties to date (Figure 1). Most of the products currently on the market are obtained from the cyanobacterium Arthrospira platensis and the green microalgae in the Chlorella spp. The Arthrospira and Chlorella spp. are the two genera most extensively cultivated worldwide for various commercial applications (mainly for the nutraceutical market) and most frequently studied for their biostimulant activities on different plant species, appearing in 49% and 56%, respectively, of the scientific publications in the field related to cyanobacteria and microalgae.

Figure 1. Genera of microalgae studied to date for their biostimulant activities with in vivo tests and currently on the market for biostimulant products, listed in descending order by number of published papers.

2. Processes and Applications of Biostimulating Algal Biomass

The production of biostimulants from algal biomass and cyanobacteria may involve the use of various techniques mainly aimed at breaking down cells by making bioactive molecules contained in or bound to cell walls available to the plant. This disruption can be achieved through physical/mechanical, chemical, or enzymatic methods [4]. The choice of extraction method is mainly dictated by the type of biomass used and the target molecules. For example, the physical/mechanical methods most commonly used for research purposes today, which involve mechanical cell wall disruption or the use of high pressure, high temperatures, ultrasound, or combinations thereof, cannot guarantee high extraction yields for micro- and macroalgae, which may have thicker cell walls than cyanobacteria [2]. Cell disruption may be followed by a phase of separation from the extract of cell residues by centrifugation or filtration or with an extraction phase using solvents in order to obtain specific fractions of the crude extract [5]. For instance, in the production of biostimulant polysaccharide extracts, polysaccharides are usually precipitated with ethanol following the physical breakdown of cells. A rather recent technique is extraction that uses supercritical CO2 as a solvent, i.e., with chemical–physical properties intermediately between those of a liquid and those of a gas, obtained at low temperatures (50 °C) and under high pressure (200–500 bars), ensuring the preservation of thermolabile bioactive compounds in biomass [4]. In the preparation of microalgal and cyanobacterial hydrolysates, the use of chemical agents, mainly acids or bases such as sulphuric acid, hydrochloric acid, and sodium hydroxide, generally results in the breakdown of the macromolecules contained in cells. However, these methods have been less and less used, as they may lead to the degradation and inactivation of some bioactive molecules contained in biomass and require the subsequent disposal of large quantities of chemical compounds [7]. Enzymatic methods use single enzymes capable of breaking cell walls and/or proteolytic enzymes that cleave peptide bonds to produce protein hydrolysates, i.e., products rich in free amino acids and soluble peptides. Extracts and hydrolysates can be applied directly to the foliar apparatus by spraying or nebulisation or to the growing medium by fertigation, in which active molecules are absorbed by the root system, or they can be used for pre-sowing treatments [1][4]. Foliar application is generally preferred to soil application, as it allows the use of lower doses of product, limits losses due to leaching, and prevents degradation by soil microorganisms. To avoid the costs associated with the extraction/hydrolysis processes, live cells can be applied directly into growth media or onto plant leaves or be used for seed treatment. Alternatively, culture media separated from microalgal biomass by filtration or centrifugation can be used directly for biostimulant treatment, exploiting the action of the compounds released by the microbial cultures [2].

3. Main Biostimulating Effects of Microalgae on Plants

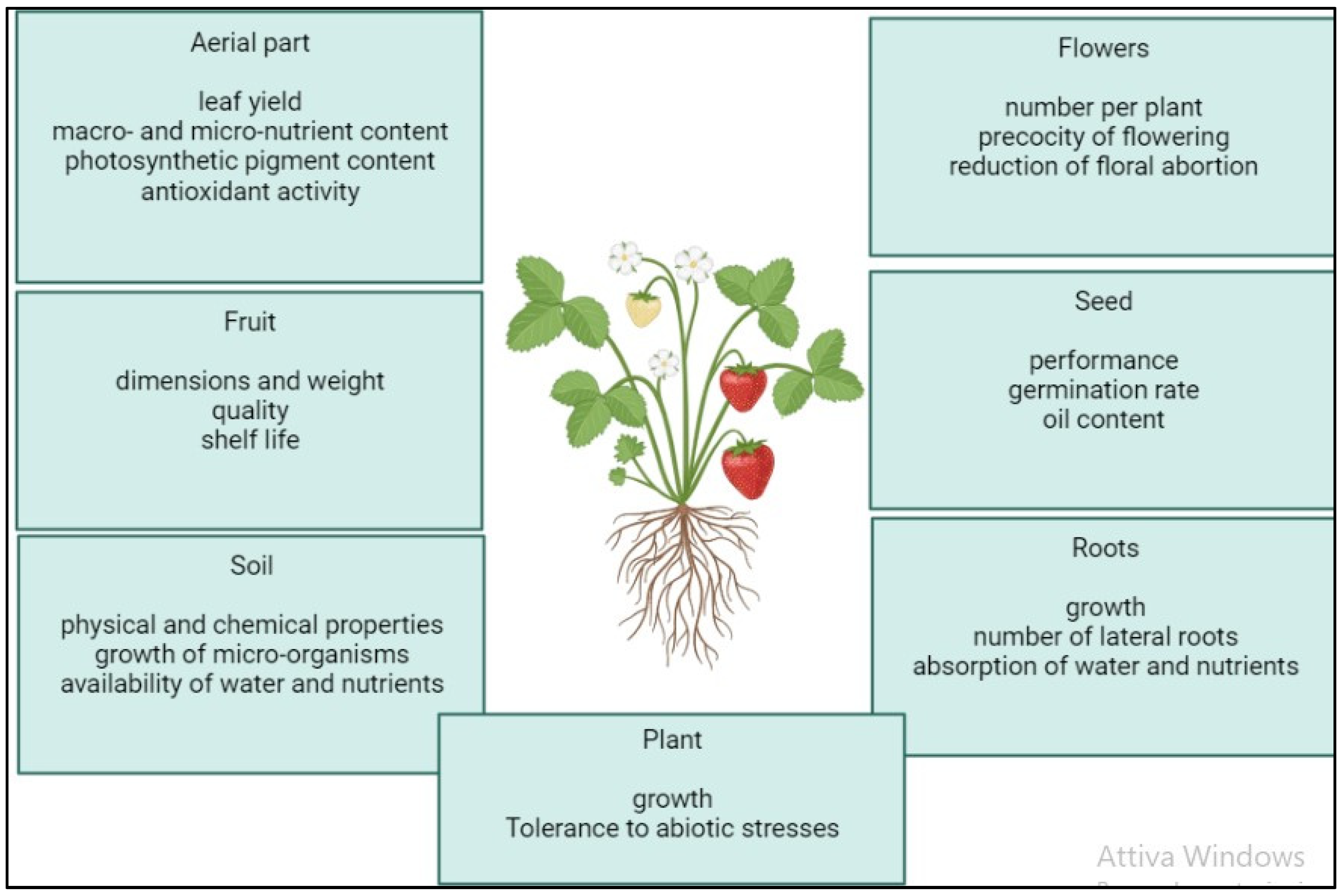

The application of microalgae and cyanobacteria or formulations derived from them (biomass, extracts, hydrolysates) on plants has been shown to produce a wide range of often interconnected beneficial effects. These responses vary depending on the microalgal species used to produce each biostimulant but also in relation to the plant species treated and the growing conditions (Figure 2) [8][9]. The phenological stage of the plant and the environmental conditions can also directly influence the success of the biostimulant treatment. Among the most common effects observed is an increase in growth and, consequently, yield in leafy vegetables (lettuce, spinach, rocket) and herbs (mint, basil) [2][8]. These increases in plant growth and fresh weight have been associated with a stimulation of the nitrogen and carbon metabolism in plants treated with microalgal extracts, whereby increases in leaf, protein, carbohydrate, and photosynthetic pigment (chlorophyll and carotenoid) content were observed [10]. The stimulation effects of the primary metabolism can be attributed to an increase in the nutrient uptake of plants subjected to the biostimulant treatment. In this sense, biostimulants can act either directly by improving soil structure and nutrient availability in the soil when applied basally or by directly influencing plant physiology when applied basally or foliarly [11]. Indeed, it is known that the inoculation of cyanobacteria into soil can promote the uptake of zinc and iron by plants through the production of siderophores [12]. In addition, the extracellular polysaccharides produced by many cyanobacterial species can stimulate rhizosphere microbiota by providing organic carbon for microbial growth and can improve soil aggregation and water retention capacity, increasing the volume of soil that can be explored by roots and indirectly promoting root growth [13]. Stimulation of root growth and development has also been observed in several studies after treatment with extracts and hydrolysates of microalgae and cyanobacteria [2][5]. For example, the use of Chlorella vulgaris and Scenedesmus quadricauda on beetroot produced positive effects on root architecture, including increases in the root length and also in the number of lateral roots and thus the root surface area for nutrient uptake [14]. These stimulation effects occurred when the biostimulant both was applied to the basal part of the plant and was absorbed directly by the roots, as well as when it was applied to the leaves and induced a concomitant increase in the macro- and micronutrient content in the plant tissues. In addition to foliar and soil application, seedling growth can also be stimulated following seed treatment in the pre-sowing phase. Seed treatment can also have the effect of increasing germination rates [8]. Due to their ability to accelerate germination and seedling development, stimulate early flowering, and increase numbers of flowers, microalgal and cyanobacterial biostimulants may also have interesting applications found in floriculture [8][15]. For example, aqueous extracts and lyophilised biomass of Desmodesmus subspicatus increased germination in vitro and accelerated development in the subsequent transplanting and acclimatisation phase in a greenhouse of the orchid Cattleya warneri [16]. The effect of biostimulants on plants does not only result in improved vegetative growth. For example, treatment of vines has resulted in a significant increase in grape yield [8]. Furthermore, the application of biostimulants can trigger biochemical processes that lead to the accumulation of important metabolites that improve the quality characteristics and shelf life of a final product [17][18]. Among these, researchers can mention an increase in the essential oil content of leaves in peppermint treated with the extracts of Anabaena vaginicola and Cylindrospermum michailovskoense [19] and an increase in total soluble solid content and reduction in weight loss during the storage of onions treated with extracts of Arthrospira platensis [20]. Although the incidence of abiotic stresses, such as drought, salinity, and temperature extremes, is expected to increase in the coming years as climate change intensifies, few strategies are available to date to mitigate the negative effects of such stresses [21]. Many abiotic factors have manifested themselves in plants as osmotic stresses, leading to the accumulation of reactive oxygen species (ROSs) that can cause severe oxidative damage to DNA, lipids, carbohydrates, and proteins [22]. It has been shown that the application of microalgae, cyanobacteria, and formulations derived from them will promote the growth and yield of certain plant species, such as rice, wheat, and tomato, under abiotic stress conditions, inducing an enhancement of the antioxidant defences in the plant tissues [2][8]. It is important to remember that the concentration of a biostimulant and its number of applications are determining factors in the success of treatment and that an increase in dose does not always correspond to an increase in positive effects on a plant [23]. In fact, it has been found in some studies that intermediate dilutions of biostimulants may be more effective in promoting growth and flowering, while application of high doses will usually reduce or even neutralise the effect. Effective doses may vary considerably depending on the plant species treated and the method of application. In general, foliar application is effective at lower concentrations than seed or soil application is [2]. In rice plants inoculated with microalgae, accumulations of phenolic acids and flavonoids have been observed in leaf tissue [3]. In addition, according to recent studies, polysaccharide extracts obtained from different microalgal strains, including Chlamydomonas reinhardtii, Chlorella rokiniana, Porphirydium spp., and Dunaliella salina, can increase the activity of antioxidant enzymes such as catalase, peroxidase, and superoxide dismutase in tomato plants subjected to salt stress [17]. Another important function of exopolysaccharides released into the soil is to sequester metal ions and sodium ions, reducing their uptake by plants and stimulating their growth in saline or polluted soils [23][24]. For example, coating maize seeds with Arthrospira platensis has led to a reduction of more than 90% of the cadmium absorbed by the roots 12 days after sowing [25][26].

Figure 2. Positive effects of the application of microalgal biostimulants on plant growth and physiology, according to the literature: improved aerial growth; improved chemical–physical and biological soil characteristics; increased fruit production and fruit size; increased germination performance and seed oil content; and improved root growth and root hairs with associated increased water and nutrient uptake.

4. Use of Microalgal Biostimulants as a Contribution to Sustainable Agricultural Practices

Agriculture consumes a huge amount of nutrients (76 and 87% of the global demand for nitrogen and phosphorus, respectively) to meet the food needs of an actively growing global population [27]. The nutrients that sustain the agricultural system are supplied by unsustainable processes or from sources that are only renewable in the long term. In addition, most fertilisers introduced into agriculture are dispersed into the surrounding ecosystem (only 17 and 20 percent, respectively, of the nitrogen and phosphorus that enter the agricultural system are then converted into the final products) because, when dispersed into the soil, they complex with organic matter, making it difficult for plants to assimilate them [28][29]. The development of sustainable alternatives for nutrient production to sustain the current agricultural production chain is therefore a priority [30]. Among the alternatives, the high contents of micro- and macronutrients make microalgal biomasses a promising source of biofertilisers [4]. Microalgae can accumulate macronutrients in the form of macromolecules in order to have a reserve and to compensate for the frequent limiting conditions to which they are often subjected in the natural environment. Their high capacity for capturing nutrients from the growth environment also makes them very promising for rehabilitating civil, industrial, and even agricultural wastewater, with the aim of establishing a circular nutrient economy and reducing the environmental impact of an increasingly intensive agricultural practice to meet the needs of a growing population [30]. Various microalgae species have been studied for their applications as biofertilisers with soil-stabilising effects and increased nutrient content as well as increased water retention capacity [31][32][33][34]. However, the mechanism responsible for biofertilisation has not yet been fully elucidated. In fact, although microalgae have high nutrient contents, the latter must also be accessible to plants. The biomass of the microalgae could then be degraded by the microbiome of the rhizosphere in order to release constituent nutrients or be subject to natural degradation to allow a sustained release of nutrients. Alternatively, the microalgal biomass could actively interact with plants, inducing the release of bioavailable forms of nitrogen in exchange for carbon compounds from the plant. In the latter case, the microalgae would also have to actively interact with the microbiome of the rhizosphere, and compatibility and survival would therefore not be guaranteed. The compatibility of microalgal biomasses with the rhizosphere microbiome has yet to be systematically investigated. Further studies are needed to establish the biological mechanisms behind the biomass fertilisation activity of microalgae as well as investigating the limitations of implementing this technology at a scale that would reduce the environmental impact of agriculture [15]. In addition to its ability to provide nutrients, the biomasses of microalgae have a wider effect on plant growth through the synthesis of phytostimulant molecules such as hormones [4]. Phytohormones found in extracts from microalgal biomasses include auxins, gibberellin-like molecules, and abscisic acid, with effects on growth and plant development as a result of biostimulatory activity on various metabolic processes, such as photosynthesis, respiration, nucleic acid synthesis, and nutrient assimilation [35]. The application of microalgal biomass extracts also appears to increase resistance to biotic and abiotic environmental stresses; however, the molecular mechanisms underlying this phenomenon remain to be elucidated [30].

5. Advantages and Critical Issues in the Use of Microalgae for Biostimulants

Although there is increasing scientific evidence on the beneficial effects of using microalgae (Figure 3), their application in agriculture is still very limited, and very few products are currently on the market, especially when compared to the large number of macroalgae products [5]. One of the main obstacles to be overcome in the commercial exploitation of microalgae relates to the cost of producing biomass, which is generally higher than for macroalgae [2]. Indeed, microalgae are cultivated in controlled and confined systems (photobioreactors and tanks) that require significant amounts of electricity, fertilisers, water, and materials for construction and operation. On the other hand, cultivation in a controlled environment is also one of the main advantages of using microalgal biomasses for biostimulant production, as it allows for greater standardisation of production processes [29]. Macroalgal biomasses, on the other hand, have biochemical and functional characteristics that can vary considerably depending on the phenological stage, environmental conditions, and nutrient availability at the time of harvest, and are therefore more difficult to standardise. In order to make microalgae biostimulants more competitive with other products on the market, it will be necessary to reduce biomass production costs, e.g., by supplementing cultivation with wastewater treatment, using waste CO2, or cultivating thermotolerant strains that do not require cooling of the crop [36][37]. Ideally, the production of biostimulants from microalgae can be integrated with the production of other products. For example, residual pellets from extraction could be used as a biofertiliser or the remaining lipid fraction could be used for the production of biofuels or to obtain polyunsaturated fatty acids with various cosmetic, medical, and nutraceutical applications or polyhydroxyalkanoates used for the production of bioplastics [2]. Residual proteins could be used to formulate food or feed for animal husbandry and aquaculture. However, the design of an efficient biorefinery system requires that the fractions that contribute most to the biostimulating action be clearly identified in order to assess the possible reuse of the remaining fractions [2].

Figure 3. Positive effects of the microalgae in the Chlorella spp., Arthrospira spp., and Scenedesmus spp. on the vegetative development of lettuce (Lactuca sativa L.).

References

- Carillo, P.; Ciarmiello, L.F.; Woodrow, P.; Corrado, G.; Chiaiese, P.; Rouphael, Y. Enhancing sustainability by improving plant salt tolerance through macro- and microalgal biostimulants. Biology 2020, 9, 253.

- Santini, G.; Biondi, N.; Rodolfi, L.; Tredici, M.R. Plant biostimulants from cyanobacteria: An emerging strategy to improve yields and sustainability in agriculture. Plants 2021, 10, 643.

- Singh, J.S.; Kumar, A.; Rai, A.N.; Singh, D.P. Cyanobacteria: A precious bio-resource in agriculture, ecosystem, and environmental sustainability. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7, 529.

- Ronga, D.; Biazzi, E.; Parati, K.; Carminati, D.; Carminati, E.; Tava, A. Microalgal biostimulants and biofertilisers in crop productions. Agronomy 2019, 9, 192.

- Chiaiese, P.; Corrado, G.; Colla, G.; Kyriacou, M.C.; Rouphael, Y. Renewable sources of plant biostimulation: Microalgae as a sustainable means to improve crop performance. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 1782.

- Guiry, M.D. How many species of algae are there? J. Phycol. 2012, 48, 1057–1063.

- Rachidi, F.; Benhima, R.; Sbabou, L.; El Arroussi, H. Microalgae polysaccharides biostiluating effect on tomato plants: Growth and metabolic distribution. Biotechnol. Rep. 2020, 25, e00426.

- Alvarez, A.L.; Weyers, S.L.; Goemann, H.M.; Peyton, B.M.; Gardner, R.D. Microalgae, soil and plants: A critical review of microalgae as renewable resources for agriculture. Algal Res. 2021, 54, 102200.

- Toscano, S.; Romano, D.; Massa, D.; Bulgari, R.; Franzoni, G.; Ferrante, A. Biostimulant applications in low input horticultural cultivation systemes. Italus Hortus 2018, 25, 27–36.

- Puglisi, I.; la Bella, E.; Rovetto, E.I.; lo Piero, A.R.; Baglieri, A. Biostimulant effect and biochemical response in lettuce seedlings treated with a Scenedesmus quadricauda extract. Plants 2020, 9, 123.

- Halpern, M.; Bar-Tal, A.; Ofek, M.; Minz, D.; Muller, T.; Yermiyahu, U. The use of biostimulants for enhancing nutrient uptake. Adv. Agron. 2015, 130, 141–174.

- Manjunath, M.; Kanchan, A.; Rajan, K.; Venkatachalam, S.; Prasanna, R.; Ramakrishnan, B.; Hossain, F.; Nain, L.; Shivay, Y.S.; Rai, A.B. Beneficial cyanobacteria and eubacteria synergistically enhance bioavailability of soil nutrients and yield of okra. Heliyon 2016, 2, e00066.

- Adessi, A.; de Carvalho, R.C.; de Philippis, R.; Branquinho, C.; da Silva, J.M. Microbial extracellular polymeric substances improve water retention in dryland biological soil crusts. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2018, 116, 67–69.

- Barone, V.; Puglisi, I.; Fragalà, F.; Piero, A.R.L.; Giuffrida, F.; Baglieri, A. Novel bioprocess for the cultivation of microalgae in hydroponic growing system of tomato plants. J. Appl. Phycol. 2019, 31, 465–470.

- Plaza, B.M.; Gomez-Serrano, C.; Acien-Fernandez, F.G.; Jimenez-Becker, S. Effetc of microalgae hydrolysate foliar application (Arthrospira platensis and Scenedesmus sp.) on Petunia x hybrida growth. Environ. Boil. Fishes 2018, 30, 2359–2365.

- Navarro, Q.R.; de Oliveira Correa, D.; Behling, A.; Noseda, M.D.; Amano, E.; Mamoru Suzuki, R.; Lopes Fortes Ribas, L. Efficient use of biomass and extract of the microalga Desmodesmus subspicatus (Scenedesmaceae) in asymbotic seed germination and seedling development of the orchid Cattleya warneri. J. Appl. Phycol. 2021, 2, 134–141.

- Mutale-Joan, C.; Redouane, B.; Najib, E.; Yassine, K.; Lyamlouli, K.; Laila, S.; Zeroual, Y.; El Arroussi, H. Screening of microalgae liquid extracts for their biostimulant properties on plant growth, nutrient uptake and metabolite profile of Solanum lycopersicum L. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 2820.

- Rodrigues, M.; Baptistella, J.L.C.; Horz, D.C.; Bortolato, L.M.; Mazzafera, P. Organic plant biostimulants and fruit quality—A review. Agronomy 2020, 10, 98.

- Shariatmadari, Z.; Riahi, H.; Abdi, M.; Hashtroudi, M.S.; Ghassempour, A.R. Impact of cyanobacterial ectracts on the growth and oil content of the medicinal plant Menthas piperita L. Environ. Boil. Fishes 2015, 27, 2279–2287.

- Geries, L.S.M.; Elsadany, A.Y. Maximizing growth and productivity of onion (Allium cepa L.) by Spirulina platensis extract and nitrogen fixing endophyte Pseudomonas stutzeri. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 169–181.

- Panda, D.; Pramanik, K.; Nayak, B.R. Use of seaweed extracts as plant growth regulators for sustainable agriculture. Int. J. Bioresour. Stress Manag. 2012, 3, 404–411.

- De Philippis, R.; Colica, G.; Micheletti, E. Exopolysaccharide-producing cyanobacteria in heavy metal removal from water: Molecular basis and practical applicability of the biosorption process. Appl. Microbial. Biotechnol. 2011, 92, 697–708.

- Arora, M.; Kaushik, A.; Rani, N.; Kaushik, C.P. Effect of cyanobacterial exopolysaccharides on salt stress alleviation and seed germination. J. Environ. Biol. 2010, 31, 701–704.

- Seifikalhor, M.; Hassani, S.B.; Aliniaeifard, S. Seed priming by cyanobacteria (Spirulina platensis) and Salep Gum enhances tolerance of Maize plant against Cadmium toxicity. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2019, 39, 1009–1021.

- Godlewska, K.; Michalak, I.; Pacyga, P.; Basladynska, S.; Chojnacka, K. Potential applications of cyanobacteria: Spirulina platensis filtrates and homogenates in agriculture. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 35, 80.

- Mogor, A.F.; Ordog, V.; Pace Pereira Lima, G.; Molnar, Z.; Mogor, G. Biostimulant properties of cyanobacterial hydrolysate related to polyamines. J. Appl. Phycol. 2018, 30, 453–460.

- Perin, G.; Yunus, I.S.; Valton, M.; Alobwede, E.; Jones, P.R. Sunlight driven recycling to increase nutrient use efficiency in agriculture. Algal Res. 2019, 41, 101554.

- Schutz, L.; Gattinger, A.; Meier, M.; Muller, A.; Boller, T.; Mader, P.; Mathimaran, N. Improving crop yield and nutrient use efficiency via biofertilization—A global metaanalysis. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 8, 2204.

- Alobwed, E.; Leak, J.R.; Pandhal, J. Circular economy fertilization: Testing micro and macro algal species as soil improvers and nutrient sources for crop production in greenhouse and field conditions. Geoderma 2019, 7, 49.

- Nisha, R.; Kaushik, A.; Kaushik, C.P. Effect of indigenous cyanobacterial application on structural stability and productivity of an organically poor semi-arid soil. Geoderma 2007, 138, 49–56.

- Stirk, W.A.; Ordog, V.; Novak, O.; Rolcik, J.; Strnad, M.; Balint, P.; van Staden, J. Auxin and cytokinin relationships in 24 microalgal strains. J. Phycol. 2013, 49, 459–467.

- Guzman-Murillo, M.A.; Ascencio, F.; Larrinaga-Mayoral, J.A. Germination and ROS detoxification in bell pepper (Capsicum anuum L.) under NaCl stress and treatment with microalgae extracts. Protoplasma 2013, 250, 33–42.

- Tredici, M.R. Mass production of microalgae: Photobioreactors. In Handbook of Microalgal Culture: Biotechnology and Applied Phycology; Richmond, A., Ed.; John Wiley: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 178–214.

- Valderrama, D.; Cai, J.; Hishamunda, N.; Ridler, N.; Neish, I.C.; Hurtado, A.Q.; Msuya, F.E.; Krishnan, M.; Narayanakumar, R.; Kronen, M.; et al. The economics of Kappaphycus seaweed cultivation in developing countries: A comparative analysis of farming systems. Aquac. Econ. Manag. 2015, 19, 251–277.

- Fortser, J.; Radulovich, R. Seaweed and Food Security. Seaweed Sustainability: Food and Non-Food Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2015; pp. 289–313.

- Liu, H. Ammonia synthesis catalyst 100 years: Practice, enlightenment and challenge. Cuihua Xuebao Chin. J. Catal. 2014, 35, 1619–1640.

- Daneshgar, S.; Callegari, A.; Capodoglio, A.; Vaccari, D. The potential phosphorus crisis: Resource conservation and possibile escape technologies: A review. Resources 2018, 7, 37.

More

Information

Subjects:

Agriculture, Dairy & Animal Science

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

911

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

08 Aug 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No