Your browser does not fully support modern features. Please upgrade for a smoother experience.

Submitted Successfully!

Thank you for your contribution! You can also upload a video entry or images related to this topic.

For video creation, please contact our Academic Video Service.

| Version | Summary | Created by | Modification | Content Size | Created at | Operation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rahima S Benhabbour | -- | 1299 | 2023-08-04 22:47:02 | | | |

| 2 | Conner Chen | Meta information modification | 1299 | 2023-08-07 05:22:59 | | |

Video Upload Options

We provide professional Academic Video Service to translate complex research into visually appealing presentations. Would you like to try it?

Cite

If you have any further questions, please contact Encyclopedia Editorial Office.

Howard, S.A.; Benhabbour, S.R. Overview of Human Reproduction and Unintended Pregnancy. Encyclopedia. Available online: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/47677 (accessed on 07 February 2026).

Howard SA, Benhabbour SR. Overview of Human Reproduction and Unintended Pregnancy. Encyclopedia. Available at: https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/47677. Accessed February 07, 2026.

Howard, Sarah Anne, Soumya Rahima Benhabbour. "Overview of Human Reproduction and Unintended Pregnancy" Encyclopedia, https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/47677 (accessed February 07, 2026).

Howard, S.A., & Benhabbour, S.R. (2023, August 04). Overview of Human Reproduction and Unintended Pregnancy. In Encyclopedia. https://encyclopedia.pub/entry/47677

Howard, Sarah Anne and Soumya Rahima Benhabbour. "Overview of Human Reproduction and Unintended Pregnancy." Encyclopedia. Web. 04 August, 2023.

Copy Citation

Hormonal contraceptives, by their nature, prevent pregnancy by regulating pituitary production of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), which act as reproductive signals for ovulation in women and sperm maturation in men. Unintended pregnancies are pregnancies that occur in advance of a preferred timeframe or completely unplanned. Each year, 121 million unintended pregnancies occur, accounting for nearly half (48%) of all pregnancies across the globe.

contraceptive

non-hormonal

long-acting

1. History of Contraceptives

The need for family planning is engraved in the history of humankind.

The Kahun Papyrus, believed to be written in Egypt circa 1825 BCE, describes early gynecological practices in hieroglyphics—including a recipe for a contraceptive suppository utilizing crocodile feces. Approximately 300 years later, the Ebers Medical Papyrus presented an herbal contraceptive suppository recipe with honey and acacia [1]. Acacia, upon fermentation, can produce lactic acid anhydride which may have been effective through vaginal pH modulation. While the use of plant-based suppositories was continued by the Ancient Greeks, they also explored oral herbal concoctions and early calendar-based family planning [2][3].

Additionally, penile sheaths have been described throughout history, though it is suggested their original purpose was to prevent transmission of disease rather than conception. These precursors to modern condoms were often made of cloth or animal organs [4][5]. The popularity of these sheaths increased during the Renaissance among the affluent until religious officials began to notice an associated population decline, henceforth declaring their use as a ‘sin’ [5].

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the world saw major advances in contraceptive science. The invention of vulcanized rubber, and eventually latex, led to the widespread production and popularity of the condom. Additionally, scientific research on the female reproductive system soared, leading to the discovery of the mammalian ovum and reproductive hormones [6]. Western attitudes on reproduction and contraception were mixed at this time, with obscenity laws often preventing the sale or use of contraceptives [7]. Rather, initial medical uses of reproductive hormones were to treat gynecological disorders, such as dysmenorrhea.

Contraceptive options began expanding in the 1950s when the spermicide Nonoxynol-9 was introduced, and in 1960 the United States approved its first contraceptive pill, Enovid [8]. Each dose of “The Pill”, as it came to be known, contained 0.15 mg of a synthetic estradiol (mestranol) and 10 mg of a synthetic progestin (noretynodrel) to inhibit ovulation. Cardiovascular concerns eventually led to the discontinuation of high-estrogen combined oral contraceptives (COCs), which have since been replaced with low- and ultra-low dose COC options as well as microdose progestin-only pills (POPs or minipills) [9]. Moreover, while surgical methods for permanent sterilization have existed since 1880, substantial utilization in the United States did not begin until the 1970s [10].

While the decades since have welcomed many new contraceptive technologies, like the intravaginal ring or contraceptive implant, only the copper IUD and on-demand barrier methods offer reversible non-hormonal contraception. Furthermore, a significant lack of male-controlled options currently prevents men from accessing highly efficacious, yet reversible, control over their reproduction [11]. While investigative male hormonal contraceptives using testosterone and its synthetic analogs have been developed and reached clinical trials, none have obtained FDA approval [12].

2. Overview of Human Reproduction

Hormonal contraceptives, by their nature, prevent pregnancy by regulating pituitary production of follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), which act as reproductive signals for ovulation in women and sperm maturation in men [13][14]. Additional effects of endogenous hormones include thinning of the uterine endometrium and thickening of cervical mucous, which may play a role in preventing pregnancy [15]. In contrast, non-hormonal alternatives are not restricted to targeting the hypothalamic–pituitary–gonadal axis and can instead impact various stages of reproduction. Broadly, these processes include gametogenesis and fertilization/implantation. Diploid primordial germ cells are the origin of all human gametes, though the process of gametogenesis occurs differently between the sexes [16].

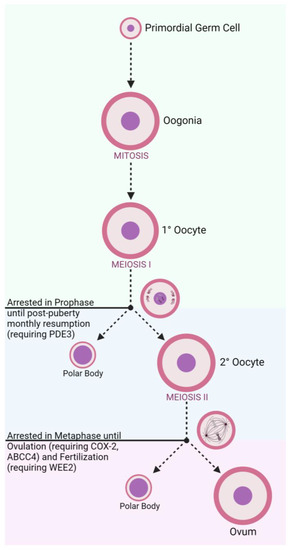

In developing female fetuses (Figure 1), oogonia divide mitotically to create primary oocytes. From there, meiosis begins to create secondary oocytes in the ovary, though this process is halted during prophase until puberty is reached and cascading effects of menstrual LH surges continue the meiotic process [17]. A secondary oocyte develops into a fully matured ovum following an additional meiotic division, though this process is arrested during metaphase until the oocyte is ovulated and fertilized [17]. These cell division steps also produce diminutive byproduct cells known as polar bodies that are later degraded. Concurrent development of follicular cells generates protective layers to encapsulate the oocyte, including the zona pellucida (ZP) which surrounds the oocyte plasma membrane [18].

Figure 1. Oogenesis and Stage-Related Contraceptive Targets.

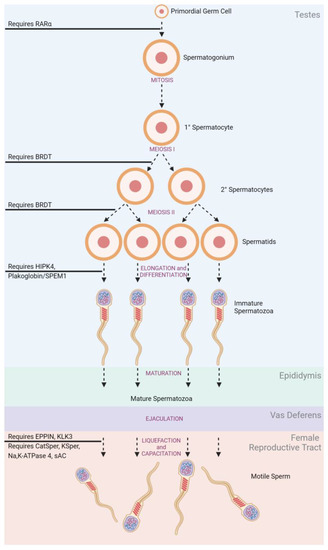

In adult males (Figure 2), spermatogonia mature under mitotic division within the seminiferous tubules of the testes [19]. The structure of the seminiferous tubules is supported by epithelial Sertoli cells which create an immunological barrier to protect sperm, known as the blood–testes–barrier (BTB) [20][21]. Produced spermatocytes remain in the seminiferous tubules and undergo a series of successive meiotic divisions to develop into spermatids. Spermatids remain anchored to Sertoli cells for continued maturing into competent spermatozoa through elongation and differentiation [21]. Spermatozoa must be produced in large numbers (sperm count) with appropriate morphology and motile function to be effective at fertilization [22]. Upon ejaculation, the spermatozoa are ‘activated’ as they travel through the epididymis and gain their progressive motility [23].

Figure 2. Spermatogenesis and Stage-Related Contraceptive Targets.

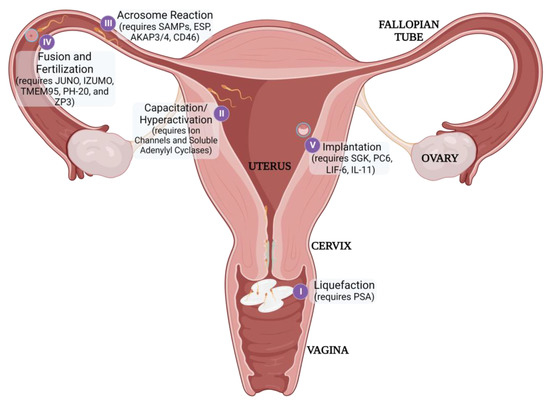

Fertilization itself requires sperm to traverse the vagina, cervix, and uterus to reach the oocyte in the fallopian tube (Figure 3). The viscosity of the cervical mucus serves as an initial barrier and filters out poor-quality sperm. Additionally, the natural pH of the vaginal environment is too acidic to support sperm viability [24]. Therefore, sperm is transported in seminal fluid that can buffer the vaginal pH to achieve an acceptable, neutral pH. Once sperm has entered the female reproductive tract, it must undergo capacitation to achieve the additional physical characteristics necessary to penetrate the protective ZP, including liquefaction, hyperactivation, and acrosomal reactiveness [25]. Immediately after ejaculation, seminal proteins (SEMG1/2) coagulate and encapsulate spermatozoa. This gelation inhibits the progression of sperm, so prostate-specific antigen (PSA) secreted during ejaculation must subsequently liquefy the matrix to release the motile sperm [26]. Henceforth, the sperm must then achieve hyperactive motility to efficiently move through the fallopian tubes and penetrate the ZP [27]. Lastly, spermatozoa need to be prepared to undergo the ‘Acrosome Reaction’ when nearing the oocyte. This reaction releases enzymes that can help degrade the ZP to further enhance penetration as well as exposing egg-binding proteins to facilitate fusion between the gametes [28].

Figure 3. Post-gametogenesis Reproductive Processes and Stage-Related Contraceptive Targets

Once fertilization has occurred, the rapidly dividing embryo must then implant successfully in the uterus to continue developing [29]. Each distinct reproductive process may serve as a potential target for non-hormonal contraception.

3. Unintended Pregnancy

Unintended pregnancies are pregnancies that occur in advance of a preferred timeframe or completely unplanned. Each year, 121 million unintended pregnancies occur, accounting for nearly half (48%) of all pregnancies across the globe. In low- and middle-income countries, the rate of unintended pregnancies averages 93% and 66%, respectively [30].

When compared to children born of planned pregnancies, children born as a result of an unintended pregnancy are more likely to be premature, of low-birth weight, and be breastfed for a shorter length of time, or not at all [31][32][33]. These children may also be at risk of developmental delays that can impact their long-term social, emotional, and academic success [32]. The mothers are also at increased risk of pregnancy unhappiness, post-partum depression, and maternal mortality [34].

Over 60% of unintended pregnancies result in abortion, with no difference in prevalence among countries with or without abortion restrictions [30]. Furthermore, 45% of these abortions are performed in unsafe conditions, without a proper method or without a trained professional [35][36]. A majority of these occur in developing countries, where 6.9 million women each year receive medical treatment as a result of an unsafe abortion [37].

Contraceptives offer robust solutions to unintended pregnancy and its associated outcomes, with models predicting that expanded access and use of contraceptives may result in up to a 33% reduction in maternal mortality rates [38].

References

- Haimov-Kochman, R.; Sciaky-Tamir, Y.; Hurwitz, A. Reproduction concepts and practices in ancient Egypt mirrored by modern medicine. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2005, 123, 3–8.

- Bujalkova, M. Birth control in antiquity. Bratisl. Lek. Listy 2007, 108, 163–166.

- Gradvohl, E. Doghearted women: The origins of the counting method. Orvostorteneti Kozlemenyek 2001, 46, 135–140.

- Khan, F.; Mukhtar, S.; Sriprasad, S.; Dickinson, I.K. The story of the condom. Indian J. Urol. 2013, 29, 12–15.

- Amy, J.J.; Thiery, M. The condom: A turbulent history. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2015, 20, 387–402.

- Sharma, R.S.; Saxena, R.; Singh, R. Infertility assisted reproduction: A historical modern scientific perspective. Indian J. Med. Res. 2018, 148, S10–S14.

- Gordon, L. The politics of population: Birth control and the eugenics movement. Radic. Am. 1974, 8, 61–98.

- Christin-Maitre, S. History of oral contraceptive drugs and their use worldwide. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2013, 27, 3–12.

- Burkman, R.; Bell, C.; Serfaty, D. The evolution of combined oral contraception: Improving the risk-to-benefit ratio. Contraception 2011, 84, 19–34.

- Chan, L.M.; Westhoff, C.L. Tubal sterilization trends in the United States. Fertil. Steril. 2010, 94, 1–6.

- Abbe, C.R.; Page, S.T.; Thirumalai, A. Focus: Sex Reproduction: Male Contraception. Yale J. Biol. Med. 2020, 93, 603.

- Long, E.J.; Lee, M.S.; Blithe, D.L. Update on Novel Hormonal and Nonhormonal Male Contraceptive Development. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2021, 106, e2381–e2392.

- Cohen, B.L.; Katz, M. Pituitary and ovarian function in women receiving hormonal contraception. Contraception 1979, 20, 475–487.

- Nieschlag, E. The struggle for male hormonal contraception. Best Pr. Res. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2011, 25, 369–375.

- Rivera, R.; Yacobson, I.; Grimes, D. The mechanism of action of hormonal contraceptives and intrauterine contraceptive devices. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1999, 181, 1263–1269.

- Larose, H.; Shami, A.N.; Abbott, H.; Manske, G.; Lei, L.; Hammoud, S.S. Gametogenesis: A journey from inception to conception. Curr. Top Dev. Biol. 2019, 132, 257–310.

- Sen, A.; Caiazza, F. Oocyte Maturation A story of arrest and release. Front. Biosci. 2013, S5, 451–477.

- Wassarman, P.M.; Litscher, E.S. Female fertility and the zona pellucida. Elife 2022, 11, e76106.

- Hess, R.A.; De Franca, L.R. Spermatogenesis and cycle of the seminiferous epithelium. Mol. Mech. Spermatogenes. 2008, 363, 1–15.

- Griswold, M.D. The central role of Sertoli cells in spermatogenesis. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 1998, 9, 411–416.

- O’donnell, L. Mechanisms of spermiogenesis and spermiation and how they are disturbed. Spermatogenesis 2014, 4, e979623.

- Guzick, D.S.; Overstreet, J.W.; Factor-Litvak, P.; Brazil, C.K.; Nakajima, S.T.; Coutifaris, C.; Carson, S.A.; Cisneros, P.; Steinkampf, M.P.; Hill, J.A.; et al. Sperm Morphology, Motility, and Concentration in Fertile and Infertile Men. N. Engl. J. Med. 2001, 345, 1388–1393.

- Sullivan, R.; Mieusset, R. The human epididymis: Its function in sperm maturation. Hum. Reprod. Updat. 2016, 22, 574–587.

- Suarez, S.; Pacey, A.A. Sperm transport in the female reproductive tract. Hum. Reprod. Updat. 2005, 12, 23–37.

- Okabe, M. Sperm–egg interaction and fertilization: Past, present, and future. Biol. Reprod. 2018, 99, 134–146.

- Anamthathmakula, P.; Winuthayanon, W. Mechanism of semen liquefaction and its potential for a novel non-hormonal contraception. Biol. Reprod. 2020, 103, 411–426.

- Suarez, S.S. Control of hyperactivation in sperm. Hum. Reprod. Updat. 2008, 14, 647–657.

- Tulsiani, D.R.; Abou-Haila, A.; Loeser, C.R.; Pereira, B.M. The Biological and Functional Significance of the Sperm Acrosome and Acrosomal Enzymes in Mammalian Fertilization. Exp. Cell Res. 1998, 240, 151–164.

- Nie, G.-Y.; Butt, A.R.; Salamonsen, L.A.; Findlay, J.K. Hormonal and non-hormonal agents at implantation as targets for contraception. Reprod. Fertil. Dev. 1997, 9, 65–76.

- Bearak, J.; Popinchalk, A.; Ganatra, B.; Moller, A.B.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Beavin, C.; Alkema, L. Unintended pregnancy and abortion by income, region, and the legal status of abortion: Estimates from a comprehensive model for 1990–2019. Lancet Glob. Health 2020, 8, e1152–e1161.

- Mokwena, K.E. Neglecting Maternal Depression Compromises Child Health and Development Outcomes, and Violates Children’s Rights in South Africa. Children 2021, 8, 609.

- Mughal, M.K.; Giallo, R.; Arnold, P.D.; Kehler, H.; Bright, K.; Benzies, K.; Wajid, A.; Kingston, D. Trajectories of maternal distress and risk of child developmental delays: Findings from the All Our Families (AOF) pregnancy cohort. J. Affect. Disord. 2019, 248, 1–12.

- Yazdkhasti, M.; Pourreza, A.; Pirak, A.; Abdi, F. Unintended Pregnancy and Its Adverse Social and Economic Consequences on Health System: A Narrative Review Article. Iran. J. Public Health 2015, 44, 12–21.

- Qiu, X.; Zhang, S.; Sun, X.; Li, H.; Wang, D. Unintended pregnancy and postpartum depression: A meta-analysis of cohort and case-control studies. J. Psychosom. Res. 2020, 138, 110259.

- Ganatra, B.; Gerdts, C.; Rossier, C.; Johnson, B.R.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Assifi, A.; Alkema, L. Global, regional, and subregional classification of abortions by safety, 2010–2014: Estimates from a Bayesian hierarchical model. Lancet 2017, 390, 2372–2381.

- Singh, S.; Remez, L.; Sedgh, G.; Kwok, L.; Onda, T. Abortion Worldwide 2017: Uneven Progress and Unequal Access; Guttmacher Institute: New York, NY, USA, 2018.

- Singh, S.; Maddow-Zimet, I. Facility-based treatment for medical complications resulting from unsafe pregnancy termination in the developing world, 2012: A review of evidence from 26 countries. BJOG Int. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2016, 123, 1489–1498.

- Haddad, L.B.; Nour, N.M. Unsafe abortion: Unnecessary maternal mortality. Rev. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009, 2, 122–126.

More

Information

Subjects:

Medicine, Research & Experimental

Contributors

MDPI registered users' name will be linked to their SciProfiles pages. To register with us, please refer to https://encyclopedia.pub/register

:

View Times:

749

Revisions:

2 times

(View History)

Update Date:

07 Aug 2023

Notice

You are not a member of the advisory board for this topic. If you want to update advisory board member profile, please contact office@encyclopedia.pub.

OK

Confirm

Only members of the Encyclopedia advisory board for this topic are allowed to note entries. Would you like to become an advisory board member of the Encyclopedia?

Yes

No

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Back

Comments

${ item }

|

More

No more~

There is no comment~

${ textCharacter }/${ maxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

${ selectedItem.replyTextCharacter }/${ selectedItem.replyMaxCharacter }

Submit

Cancel

Confirm

Are you sure to Delete?

Yes

No